Introduction

Why do voters fail to hold corrupt politicians accountable? Studies have found evidence for “implicit trading” in corruption voting where voters put higher weight on economic incentives and downplay a history of corruption (Rundquist, Strom, and Peters Reference Rundquist, Strom and Peters1977).Footnote 1 Voters may also turn a blind eye to corruption because they are ignorant about the issue or lack credible information to mobilize political punishment for politicians’ malfeasance (Fackler and Lin Reference Fackler and Lin1995; Chang, Golden, and Hill Reference Chang, Golden and Hill2010; Weitz-Shapiro and Winters Reference Weitz-Shapiro and Winters2017). The institutional contexts can play a role by altering “clarity of responsibility” and helping voters correctly attribute poor performance correctly to inept politicians (Tavits Reference Tavits2007; Charron and Bågenholm Reference Charron and Bågenholm2016; Krause and Méndez Reference Krause and Méndez2009). Studies also emphasize the contextual environment at the time of malfeasance, such as economic conditions, the apparent externalities of corruption, or the general prevalence of corruption (Klašnja and Tucker Reference Klašnja and Tucker2013; Konstantinidis and Xezonakis Reference Konstantinidis and Xezonakis2013; Fernández-Vázquez, Barberá, and Rivero Reference Fernández-Vázquez, Barberá and Rivero2016).

This article theorizes an asymmetric partisan bias in copartisan assessment of corruption and voting behavior. Partisan bias exists across different party lines, but the degree of bias might vary depending on the type of partisanship. Especially in post-authoritarian countries, supporters of authoritarian legacy parties may be more susceptible to partisan bias than supporters of other parties due to their heightened partisan attachment. As former ruling parties under dictatorship, authoritarian legacy parties still drive political competition (Loxton and Mainwaring Reference Loxton and Mainwaring2018; Cheng and Huang Reference Cheng, Huang, Loxton and Mainwaring2018) and political attitudes and behavior in many post-authoritarian democracies (Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2017; Kang Reference Kang2018; Chang, Zhu, and Pak Reference Chang, Zhu and Pak2007; Hong, Park, and Yang, Reference Hong, Park and Yang2022). Among sixty-five Third Wave democracies, authoritarian legacy parties operate in forty-seven, twenty-eight of which won more than 20 percent of the vote share in recent elections (see Table A.1; Loxton and Mainwaring Reference Loxton and Mainwaring2018). The enduring effects of authoritarian legacies may manifest in assessments of corruption differing along partisan lines.

I argue that corruption voting is asymmetric, with authoritarian legacy partisans holding stronger partisan bias at the party and voter levels. Supporters of authoritarian legacy parties (ALPs) possesses a psychological linkage to the party due to their collective nostalgia for the authoritarian past and the achievements of the previous regime. Individuals who share these values develop a social identity supporting the former authoritarian regime and establish strong affect toward the ALP. In addition, ALP partisans are attracted to the political ideologies of conservatism and authoritarianism which ALPs inherited from the former ruling parties. ALP partisans are likely to have higher loyalty to parties that satisfy their psychological need for stability and, therefore, are to be especially likely to engage in biased assessment of copartisan politicians. With this heightened partisan bias, ALP partisans are less likely to punish copartisan candidates for their poor performance, when compared to the levels of punishment encountered among other types of partisans.

I investigate these arguments using multiple empirical strategies and employing data collected at the district and individual levels from South Korea. I first provide evidence that ALP candidates faced no discernible loss in votes for their malfeasance compared to the punishment that candidates from non-ALP parties faced. Individual-level analysis of survey data shows greater copartisan bias among ALP supporters during the 2016 legislative election. I find a greater copartisan bias among ALP supporters compared to their main opposition party supporters. Together these results provide evidence of asymmetric partisan bias in voters’ retrospective evaluation of candidates in post-authoritarian democracies. Rather than displaying equivalent bias across different parties, supporters of ALP and non-ALP parties appear to have discrepant reactions to information about corruption, thus holding politicians accountable to varying degrees.

Asymmetric partisan bias in corruption voting

Bringing partisanship into the study of corruption voting

Scholarship on the relationship between corruption perceptions and voting behavior has focused on factors that may affect voters’ performance-based evaluation of incumbents, such as voters’ capability to interpreting information about corruption (Fackler and Lin Reference Fackler and Lin1995; Rundquist, Strom, and Peters Reference Rundquist, Strom and Peters1977; Chang, Golden, and Hill Reference Chang, Golden and Hill2010; Winters and Weitz-Shapiro Reference Winters and Weitz-Shapiro2013); clarity of responsibility as determined by the institutional environmentFootnote 2 (Tavits Reference Tavits2007; Charron and Bågenholm Reference Charron and Bågenholm2016; Krause and Méndez Reference Krause and Méndez2009); and environmental factors, such as economic conditions, externalities of corruption, and the general prevalence of corruption in different countries (Klašnja and Tucker Reference Klašnja and Tucker2013; Konstantinidis and Xezonakis Reference Konstantinidis and Xezonakis2013; Fernández-Vázquez, Barberá, and Rivero Reference Fernández-Vázquez, Barberá and Rivero2016). While this field investigates the individual- and system-level factors that explain either the presence or absence of voter accountability for corrupt politicians, investigation into the role of political parties and partisanship as agents of political accountability has received limited attention.

Anduiza, Gallego, and Muñoz's (Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013) work broke out of tradition and introduced an additional dimension of partisanship by introducing motivated reasoning to the field. They argued that in the same way that levels of education or types of political institutions can affect information credibility, individual affiliation to political parties can also lead voters to assign differing levels of credibility to corruption information. Motivated by their partisan orientation, voters may downplay corruption information about copartisan politicians when that information is incongruent with voters’ prior political beliefs and attitudes, while simultaneously treating corruption information about outpartisan politicians as more credible and therefore react more severely. Anduiza, Gallego, and Muñoz (Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013) find that when a voter is aligned with the party charged with corruption, they perceive information about corruption as less severe than similar information about a candidate from a different party.

This conclusion is in line with partisan bias work that finds voters from different political parties tend to look through a partisan lens when they interpret the political world (Bartels Reference Bartels2000; Achen and Bartels Reference Achen2017), but are individuals from different partisan groups likely to be biased to the same degree? In the next section, I discuss work on the distribution of partisan bias and argue that partisan bias is stronger among ALP partisans, making them less responsive to corruption information and more likely to reelect corrupt incumbents than partisans of a different party.

Symmetric and asymmetric partisan bias

Studies on political behavior have established that people often interpret and participate in the political world in a way that satisfies their preexisting political orientation (Bartels Reference Bartels2000; Huddy, Mason, and Aarøe Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015; Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Kuklinski, Quirk, Peyton and Verkuilen2007). Just as these “enduring partisan commitments” shape political attitudes (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1980, 135), partisan bias encourages people to vote based on partisan loyalty (Bartels Reference Bartels2000), interpret political or economic events differently (Bartels Reference Bartels2002), exhibit differing levels of presidential approval (Lebo and Cassino Reference Lebo and Cassino2007), and direct individual decisions and behaviors even in nonpolitical issues in different ways (Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015). Partisan identity is deeply ingrained in individual voters’ perceptions, coloring their beliefs and interpretations of the world and in turn strengthening their favor for one party and disapproval for another.

Two streams of scholarship have developed to investigate how partisan bias is distributed across partisan types with a focus on American voters: one aligns with the symmetry hypothesis and the other an asymmetry hypothesis.Footnote 3 The symmetry hypothesis claims that liberals or conservatives do not hold a “monopoly on bias” and predicts equivalent partisan bias across different ideological fronts (Ditto et al. Reference Ditto, Liu, Clark, Wojcik, Chen, Grady, Celniker and Zinger2019, 275). Regardless of ideology, people are susceptible to motivated reasoning in order to achieve attitude congruence and avoid dissonance with their prior beliefs about the political world (Collins, Crawford, and Brandt Reference Collins, Crawford and Brandt2017; Ditto et al. Reference Ditto, Liu, Clark, Wojcik, Chen, Grady, Celniker and Zinger2019). People of differing age, gender, occupation, or income may show different levels of motivated reasoning, and partisanship is not unique in this regard. On the other hand, the asymmetry hypothesis argues that there is a higher level of partisan bias among conservatives than liberals, originating in the psychological rigidity of the former. This line of thinking emphasizes the cognitive motivation of conservatives, stemming from the psychological need to manage uncertainty and fear (Jost et al. Reference Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski and Sulloway2003; Jost Reference Jost2017). This leads to ideological asymmetries between conservatives and liberals, where conservatives have a higher predisposition than liberals to dogmatism, cognitive rigidity, a need for closure and order, and intolerance of ambiguity (Jost Reference Jost2017).

In this article, I develop and test expectations about asymmetry in copartisan favoritism and lack of punishment for corruption among conservative partisans with special focus on authoritarian legacy party supporters. Authoritarian legacy parties (ALPs) display stronger partisan bias through heightened partisan attachment in two ways: (1) ALPs’ adherence to conservative and traditional ideologies with origins in the previous regime satisfies the psychological needs of their partisans; and (2) authoritarian nostalgia from voters leads to affective partisanship, resulting in greater attachment and bias among ALP supporters.

Authoritarian legacies and asymmetric partisan bias in corruption voting

While democratic transition spurs reconstruction of the political and social landscape, former authoritarian ruling parties often manage to survive through this process. Often by signing a pact with the opposition groups, successor parties design their exit strategies in a way that secures the party's survival even after the regime that they led collapses (O'Donnell Reference O'Donnell1994; Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018). Studies have examined the survival strategies of authoritarian successor parties, including Grzymała-Busse's (Reference Grzymała-Busse2002) work that finds successors’ survival is supported by parties’ flexibility in times of change. Other successor parties have benefited from their “authoritarian inheritance” of organizational structure and reputation from past achievements (Loxton and Mainwaring Reference Loxton and Mainwaring2018), and many former ruling parties are still standing strong with the majority of them winning more than 20 percent of the total vote share in recent elections (see Table A.1 in Appendix).

However, scholarship on authoritarian legacies has not yet considered a continued presence of authoritarian nostalgia among voters and political utilization of it by successor parties. Contrary to the finding that one of the key factors of successor party survival was the party's “break from the past” (Grzymała-Busse Reference Grzymała-Busse2002), recent elections have demonstrated the persistent politicization of authoritarian legacies and its contribution to electoral success in post-authoritarian democracies (Kang Reference Kang2018; Seligson and Tucker Reference Seligson and Tucker2005; Chang, Zhu, and Pak Reference Chang, Zhu and Pak2007; Gherghina and Klymenko Reference Gherghina and Klymenko2012; Hong, Park, and Yang, Reference Hong, Park and Yang2022). These authoritarian successors often seek their legitimacy from the authoritarian past and garner electoral support by evoking authoritarian nostalgia among their supporters. For example, ALPs in Korea and Taiwan invoke their proven reputation for economic development and national security from developmental authoritarian regimes, which is used to mobilize popular support from voters in times of economic and external threats (Cheng and Huang Reference Cheng, Huang, Loxton and Mainwaring2018; Kang Reference Kang2018).

I argue that ALPs intentionally invoke authoritarian legacies in order to take advantage of their partisans’ heightened attachment in two ways, where an ALP is an authoritarian successor party that frequently references the authoritarian past. First, ALP partisanship based on authoritarian nostalgia for the former regime contributes to stronger affective partisanship among the supporters of these parties. Here, authoritarian nostalgia refers to an individual's positive perception of the authoritarian past, emphasizing the achievements of the autocratic regime and discounting democratic values and norms. In new democracies, authoritarian nostalgia functions as a collective sentiment that is shared among citizens. Studies have found that collective nostalgia serves as motivation for strong membership in certain groups and promotes a sense of inclusion and exclusion (Wildschut et al. Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014; Smeekes, Verkuyten, and Martinovic Reference Smeekes, Verkuyten and Martinovic2015). When individuals share a positive sentiment about the political past, they construct a collective nostalgic reverie that evokes happy memories of the past and generates a shared social identity (Smeekes Reference Smeekes2015; Lammers and Baldwin Reference Lammers and Baldwin2020). This shared sentiment may develop into group-related attitudes and behavior via ingroup preferences and outgroup evaluations, such as stronger ingroup commitment, greater distance to outgroup members, and hampered intergroup relations (Smeekes, Verkuyten, and Martinovic Reference Smeekes, Verkuyten and Martinovic2015; Smeekes Reference Smeekes2015; Wildschut et al. Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014).

In post-authoritarian democracies, the nostalgic rhetoric of politicians has provoked repeated political tension while also soliciting popular support from nostalgic voters, using the issue of authoritarian evaluation as a key political cleavage (Andrews-Lee and Liu Reference Andrews-Lee and Liu2021; Kim Reference Kim2014). Nostalgic intellectuals have attempted to reshape and reconstruct the former dictatorship under more favorable narratives by publishing academic articles or revising history textbooks (Yang Reference Yang2021). With this frequent utilization of authoritarian nostalgia in the political sphere, a longing for the former dictatorship can function as an effective rallying cry and facilitate strong ingroup sentiment among those who sympathize and share the core values with the past, such as economic prosperity, political stability, and social cohesion (N.-y. Lee Reference Lee, Lee, Lee, Kang and Park2020; Choi Reference Choi2019). Outgroup sentiment further contributes to the role of authoritarian nostalgia as a driver of social identity. In many post-authoritarian countries, the authoritarian political cleavages which developed under former dictatorships persist in major political debates. For example, in South Korea, the old political rhetoric of accusing a liberal political opponent of communism still resonates in political discourse, and such dogged political rhetoric results in a stronger outpartisan distance across partisan groups (Lee Reference Lee2015; Shaw Reference Shaw2022). Thus, the historical perspective of citizens can serve as a key tool for distinguishing friend from foe. Citizens with authoritarian nostalgia breed a social identity that can shape stronger group sentiment towards those who share similar views of the authoritarian past and towards an ALP and its partisans that frequently reference back to the past.

Second, authoritarian legacy parties’ linkages to conservatism and authoritarianism appeal to the psychological need for stability and order among their partisans. Authoritarian legacy parties find their ideological origins in the authoritarian past and emphasize policy goals such as hierarchical social order, guided economic and social development, and national security (Cheng and Huang Reference Cheng, Huang, Loxton and Mainwaring2018; Slater and Wong Reference Slater, Wong, Loxton and Mainwaring2018). While these values were introduced to consolidate symbolic power and to ensure the political security of a dictator, ALPs maintain issue dominance in these traditional policy goals even after democratic transition (Cheng and Huang Reference Cheng, Huang, Loxton and Mainwaring2018), and this ideology continues to serve to satisfy the psychological need for resistance to change and ambiguity among voters in post-authoritarian societies. These ideological legacies from an authoritarian past amplify the epistemic motives of cognitive rigidity among ALP partisans and strengthen their attachment to and partisan bias towards ALPs (Kim-Leffingwell Reference Kim-Leffingwell2022).

The theoretical argument above suggests that authoritarian legacy partisans tend to have higher partisan bias via two sources: a stronger affective partisanship that originates in authoritarian nostalgia and ALPs’ conservative ideological and programmatic positions. The conservative and authoritarian ideological positions of ALP supporters suggest greater partisan bias compared to liberal voters due to their psychological rigidity, and some degree of the ALP supporters’ nostalgic sentiment leads to more heightened favoritism toward copartisan politicians who evoke this nostalgia. In comparison, I expect partisan bias to be smaller with conservative but non-nostalgic voters. For example, some voters with high conscientiousness may support an ALP due to their support for conservative ideology (Perry and Sibley Reference Perry and Sibley2012), but they may not experience authoritarian nostalgia because of their predisposition to civic duties to the political system they live in (Gallego and Oberski Reference Gallego and Oberski2012; Dawkins Reference Dawkins2017). Thus, partisan bias is expected to be lower with these voters compared to conservative and nostalgic voters because authoritarian nostalgia serves as an additional source of partisan bias among conservative voters. With this elevated partisan loyalty among ALP partisans, I expect asymmetric corruption voting, where ALP partisans and partisans of different parties behave differently, evidenced by a lower level of punishment for corruption among ALP partisans than non-ALP partisans.

This article focuses on copartisan bias across different partisan groups rather than on the difference between copartisan and outpartisan bias within a single partisan group. Previous work on corruption voting by Anduiza, Gallego, and Muñoz (Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013) has found evidence for the latter type of partisan bias, where voters treat corruption information less seriously when the accused candidate is from the same party compared to when they are from other parties. In addition, in one of their key findings, authors did report signs of asymmetric partisan bias across party lines showing that copartisan bias is larger among sympathizers of a conservative party, compared to those of a more liberal counterpart. While the authors comment on the possible effects of the general prevalence of corruption among right-wing party candidates, the did not explore this additional research question. This article departs from a cross-partisan comparison strategy, instead examining varying degrees of copartisan bias.

With an emphasis on authoritarian and conservative ideologies, I predict greater partisan bias among supporters of former ruling parties, especially parties from former right-wing dictatorships that emphasized nationalist, populist, and anti-communist ideologies (Dinas and Northmore-Ball Reference Dinas and Northmore-Ball2020; Kim-Leffingwell Reference Kim-Leffingwell2022). Of forty-five former authoritarian regimes, twenty countries adopted such rightist ideologies as ruling principles, while twenty-five countries employed leftist ideologies.Footnote 4 However, I also expect the partisan bias to be paralleled among ALP partisans across former left-wing regimes. The nominal emphasis on socialism among leftist regimes contrasts with the rightist counterparts, but ALPs’ emphasis on (relative) social and economic stability under communism can also facilitate the psychological need for stability and order among citizens. This appeal may prove more effective among “left authoritarians” in post-communist countries who self-identify as leftist but exhibit support for authoritarian values and ideals over democratic ones (Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2020). There is also a strong presence of left authoritarians in countries with histories of greater state penetration and indoctrination of society through mass education and communication (Dinas and Northmore-Ball Reference Dinas and Northmore-Ball2020; Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2020). Thus, while the current article tests the main hypotheses with data collection from a former right-wing dictatorship, the author expects to find similar patterns of asymmetric partisan bias across different types of former authoritarian regimes.

Empirical strategy

I test the asymmetry of partisan bias in corruption voting through multiple empirical strategies with South Korean elections data and individual-level survey data. The main focus of the analysis is to examine voters’ behavior when they receive corruption information about candidates. South Korean elections are useful empirical laboratories for several reasons. First, an authoritarian legacy party, the People Power Party, remains one of two major parties and occupies the conservative domain in the ideological spectrum.Footnote 5 The origin of the People Power Party dates back to its authoritarian predecessor, the Democratic Republican Party, which was the ruling party of the former dictator Park Chung-Hee. The party has maintained its dominant position in Korean politics, often renaming itself but preserving its party brand of political and economic modernization. Park and his successors have stressed their roles in overseeing economic growth and maintaining strong national security under the former dictatorship, and voters find the party more suitable for implementing related policies even today (Cheng and Huang Reference Cheng, Huang, Loxton and Mainwaring2018; Kang Reference Kang2018).

Second, partisans in South Korea are faced with similar alternatives at elections regardless of party alignment: with two-party competition, voters in either the conservative or liberal camp are equally limited in alternative party choices within the same ideological orientation. Since alternatives are limited for both sides, the competitive environment is a good setting to compare voters’ reactions to corruption information about copartisan candidates. Third, corruption is a central issue in South Korean politics. South Korea has a moderate level of corruption, scoring around 53–59 on a score from zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean) from 2015 to 2019 in the Corruption Perception Index (Transparency International 2019). The Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission reported in 2010 that of the 1,500 government officials who lost their jobs from 2005 to 2009, more than 1,200 left their office due to corruption charges including bribery and embezzlement (Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission 2010).

Despite the centrality of this issue, scholarly attention to corruption voting in Korea has been limited, and empirical findings of corruption voting have been mixed. Studies have mainly focused on overall criminal records by aggregating different types of crimes in their measures, finding that the effects of criminal records are inconclusive at elections (Park and Kim Reference Park and Kim2009; Lee Reference Lee2012). A recent study employs a more sophisticated methodological approach and finds that candidates with criminal records are more likely to have a lower vote share and lower probability of winning at elections (Song and Yoon Reference Song and Yoon2016). This study finds evidence of conventional retrospective voting behavior among Korean voters but is limited in differentiating the electoral effects across different types of criminal records and partisan groups.

Lastly, election laws in Korea provide a good setting to test voters’ reactions to corruption because candidates’ criminal records can only be disclosed near to the election period. Korean privacy laws restrict public access to politicians’ criminal records in non-election times. Only a few weeks before an election, the Korean National Election Commission (NEC) distributes an election flyer to every household with eligible voters containing information on candidates, including their income levels, military-service record, tax payment history, and criminal history. Since the 2004 legislative election, election flyers containing the above-listed information have been sent to each household, making candidates’ information highly accessible to voters during the election period. A voter can read candidates’ previous convictions of corruption in the criminal history section, with the receipt of corruption information through flyers serving as the treatment in the election data analysis of this study.Footnote 6

I test my hypotheses with empirical evidence from different methodological approaches to better examine voters’ actual behavior at elections and how the general perception of corruption relates to voter decisions. The empirical debate about whether voters hold corrupt politicians accountable is ongoing, and numerous studies have employed experimental methods to disentangle the causal effect of corruption information on voting behavior (Klašnja and Tucker Reference Klašnja and Tucker2013; Weitz-Shapiro and Winters Reference Weitz-Shapiro and Winters2017; Agerberg Reference Agerberg2020). While many studies have deepened our understanding of the central mechanisms that voters may employ when presented with certain corruption information, a recent meta-analysis of experimental studies found potential biases in their findings (Incerti Reference Incerti2020). Analyses from this study suggest that experimental results may not mirror real-world voter behavior, either through a failure to account for the costliness of changing voter decisions in surveys or through underreporting treatment effects due to possible issues of weak treatment and noncompliance in the field experiments. Another study fielded in Brazil demonstrates discrepancies in voter behavior between experimental and real-world settings: while voters sanction hypothetical politicians with corruption convictions, they show no discernible reaction to the same information about real-world politicians (Boas, Hidalgo, and Melo Reference Boas, Daniel Hidalgo and Melo2019). Thus, the empirical analysis in this article focuses on the real-world reactions of voters to corruption information by testing the main arguments with observational datasets collected at both the district and individual levels.

Empirical analysis

The district-level analysis

With the district-level analysis, I test my hypotheses with data collection from the 2004, 2008, and 2016 legislative elections,Footnote 7 with final voting results retrieved from the NEC. Using real-world electoral data, this analysis provides evidence for partisan differences in “punishment” for corruption convictions for an ALP candidate and a Democratic party candidate. As voters with any partisanship are equally exposed to corruption information about copartisan candidates, comparing election results of corrupt candidates at historical elections serves to provide evidence for the theorized mechanism.

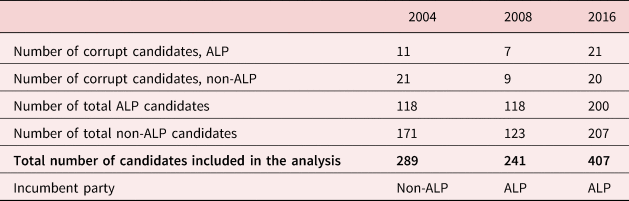

The main outcome variable is the vote share of each candidate who participated in the elections. The main explanatory variable measures the previous corruption convictions of each candidate, with a candidate coded as 1 if he or she has any history of corruption convictions. The dataset only includes candidates who have previously served in office or in government before each election so that all candidates in the sample could potentially have been accused of acting corruptly while in office. The dataset contains around 240–400 candidates from each election.Footnote 8 There were 32 candidates with corruption convictions in 2004, 16 in 2008, and 41 in the 2016 election (Table 1).Footnote 9

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the number of candidates from each election

The regression models include a set of control variables that may confound the relationship between key variables. Candidates’ age and gender comprise individual-level control variables to account for underlying variation across candidates. The model also includes proportional representation votes (PR vote) from the previous election to account for differential baseline support across parties in each district.Footnote 10 I also include region fixed effect in all regression models, based on studies that have investigated the effects of regionalism in South Korean politics (Kwon Reference Kwon2004; Horiuchi and Lee Reference Horiuchi and Lee2008).

The district-level empirical analysis takes two steps: I first divide the candidate pool into two partisan groups, and then regress vote share on corruption convictions within each partisan group, calculating the effects sizes of βALP from the authoritarian legacy parties, and β¬ALP from the opposition parties. This first step examines how politicians with corruption convictions lose vote share in comparison with their colleagues and estimates the level of copartisan bias for each partisan group. I further include interaction models with a pooled dataset with both partisan groups to compare the conditional effects of corruption voting. The main hypothesis of this article examines the differing effects of corruption voting across candidates’ partisanship and previous history of corruption convictions. A model specification with an interaction term may serve to test the main hypothesis, but the small number of treated candidates, only around 6–10 percent of the samples, raises concerns of limited statistical power and inaccurate representation of the interested relationship (Brookes et al. Reference Brookes, Whitely, Egger, Smith, Mulheran and Peters2004; Marshall Reference Marshall2007). To account for these issues, I present the main empirical results from both subgroup and interaction models in the main text below.

In the second step, I examine the asymmetry of partisan bias by conducting a simulation-based test of the coefficients from two subgroup models. I draw a random sample of one hundred observations from the original datasets 10,000 times and derive a coefficient for each simulation. With the simulated coefficients, I compare the distributions of coefficients across partisan groups and test the divergence in electoral outcomes between candidates with and without corruption convictions within each partisan group. The simulation test is designed to compare the diverging patterns of electoral results between ALP and non-ALP partisans through a large number of simulations. This analysis provides additional context on the varying consequences for political corruption for ALP and non-ALP candidates. I expect the distribution for the Democratic Party candidates to be clustered away from zero, indicating more severe punishment for corruption, while the distribution for ALP candidates to be closer to zero, indicating greater partisan bias.

Results from the legislative election dataset

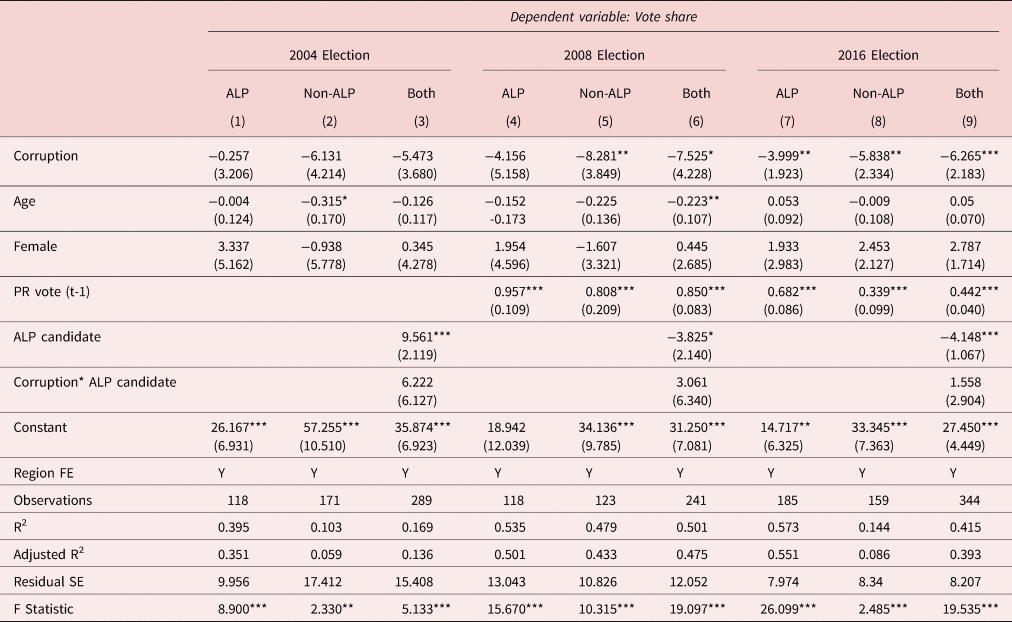

Table 2 includes results from the legislative election analysis and finds support for asymmetric corruption voting across partisan types. Coefficients are from regression models with separate partisan groups from the 2004 (Models 1–3), 2008 (Models 4–6), and 2016 elections (Models 7–9).Footnote 11 Comparing results from the two-party groups highlight a striking discrepancy in election outcomes across party lines. The results for non-ALP candidates follow conventional expectations for corruption voting, where candidates with corruption convictions lost vote share compared to their non-corrupt colleagues in all three elections. Democratic Party candidates with political corruption lost around six to eight percentage points of vote share relative to other candidates from the same party. ALP candidates, on the other hand, did not face discernible consequences for their previous corruption convictions. Coefficients from 2004 and 2008 are inconclusive and statistically insignificant. The results from these two elections evidence the presence of asymmetric corruption voting for ALP candidates, and this finding is consistent regardless of the partisanship of the incumbent government, with the non-ALP party in power in 2004 and the ALP in 2008. The regression coefficients are negative and significant from both party groups in 2016, but ALP candidates continued to face milder electoral consequences compared to non-ALP party counterparts.

Table 2. Corruption convictions and vote share changes in three elections

Note: Ordinary least squares regression models of corruption convictions on vote share from 2004, 2008, and 2016 Korean legislative elections data. All models include control variables of candidates’ age, gender, and PR vote share for each district from the previous election. The PR vote share is not included in the 2004 election since this election was the first election that introduced party-list proportional representation. *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

Empirical findings in Table 2 highlight that candidates with corruption convictions faced different responses for their malfeasance depending on which party they belong to. Results with the interaction term (Corruption*ALP candidate) further support the asymmetry between ALP and non-ALP candidates with positive coefficients, indicating more favorable electoral outcomes for political corruption among ALP candidates. The results from interaction models agree with those from the subgroup analysis, but the coefficients are not significant at the conventional levels. This finding might originate from the small sample size with the interaction term, and I account for this issue and provide further empirical evidence for the asymmetry in corruption voting with a simulation-based test (see Figure A.2 in Appendix).

The distributions from 10,000 simulation-based coefficients highlight a clear divergence between ALP and non-ALP candidates: ALP candidates faced no discernable punishment for corruption, compared to non-ALP candidates who experienced a significant decrease in their vote share when corruption is revealed. This finding is remarkable as the effect sizes are derived from comparing vote shares for copartisan candidates rather than those of candidates across different parties: non-ALP candidates faced heavy punishment for corruption compared to other candidates without corruption convictions from the same party, while ALP candidates with corruption convictions managed the election as well as others without convictions from the same party. This analysis provides evidence for the asymmetric hypothesis of partisan bias in corruption voting in South Korean legislative elections.

The political landscape around the 2016 election suggests an explanation for the larger reaction to corruption among ALP candidates. The election took place at the dawn of the corruption scandals involving the incumbent President Park, with public discontent against the sitting president accumulating since the Sewol ferry disaster in 2014.Footnote 12 Park's cronyism and lack of communication with the public dragged down her approval ratings to 30 percent, making the legislative election into a “referendum on Park” (Jang Reference Jang2016). Factional conflicts within the Saenuri Party (the ALP party's name at the time) and the creation of a new center-right party further triggered ALP partisans to react more harshly to corruption convictions compared to previous elections. In this election, the opposition Democratic Party won a landslide victory by adding 21 additional seats to its previous 102 seats, compared to the governing Saenuri Party's loss of 24 seats and its majority in the 300-member National Assembly.

Individual-level survey analysis

With the individual-level analysis, I analyze how individuals employ corruption perception at elections using survey data from the fifth wave of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES 2020). Investigating the main arguments of this article requires individual-level analysis, but survey datasets often fail to include all the necessary variables needed to analyze voters’ perception of corruption and its effects on related behavior. Even within the CSES studies, only two waves include questions on corruption perception (second and fifth), and the second wave does not record respondents’ electoral districts. The fifth wave of CSES provides individual responses to corruption perception and political preferences from a month after the 2016 legislative election. This dataset includes measures of the level of corruption, voter partisanship, vote choice, and electoral districts. The main analysis examines voter choices in relation to perceived level of corruption. The corruption perception variable comes from answers to the question, “How widespread do you think corruption such as bribe taking is among politicians in South Korea?”

I compare differences in corruption voting across party lines in three steps: first, with the recorded electoral district of each survey respondent, I create a variable recording the partisanship of incumbent legislators across 116 districts included in the dataset with election data retrieved from the NEC. Second, I construct the outcome variable, VoteIncumbent, coded 1 if a respondent voted for a copartisan incumbent of her district and 0 if she voted for a different party candidate. Third, I analyze differential copartisan bias in corruption voting by running the main regression separately for ALP-incumbent districts and the opposition Democratic Party (DemParty) districts. The main regression model includes an interaction term between the main explanatory variable, Corruption perception, and voter partisan identification. By analyzing copartisan bias separately across incumbent partisanship, I investigate how each group of partisans responds differently to perceived levels of corruption.

This individual-level analysis can highlight differing corruption voting behavior between ALP and Democratic Party supporters. By using district-level incumbents rather than the governing or president's party for the incumbent voting variable, I can better reflect the electoral calculations that voters employed during the 2016 legislative election. The CSES survey question's general wording on corruption perception may raise concerns about not directly connecting to the district legislators, but with the survey conducted right after the legislative election, I postulate that this question resonates with the perceived level of corruption connected to legislators of each district.

Results from individual-level analysis

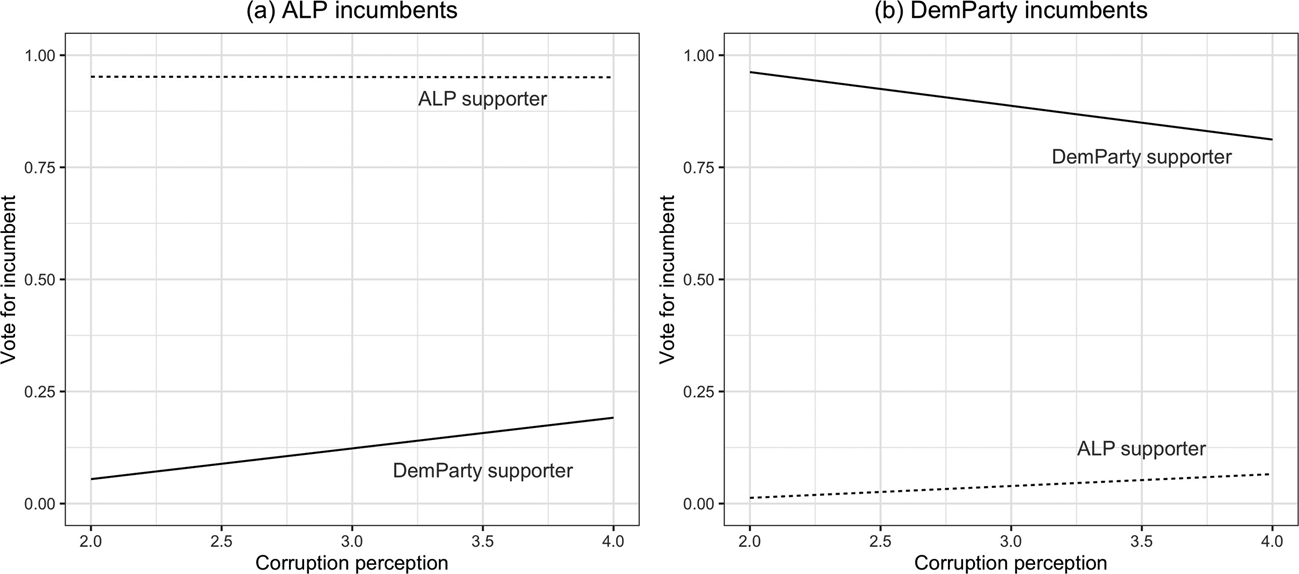

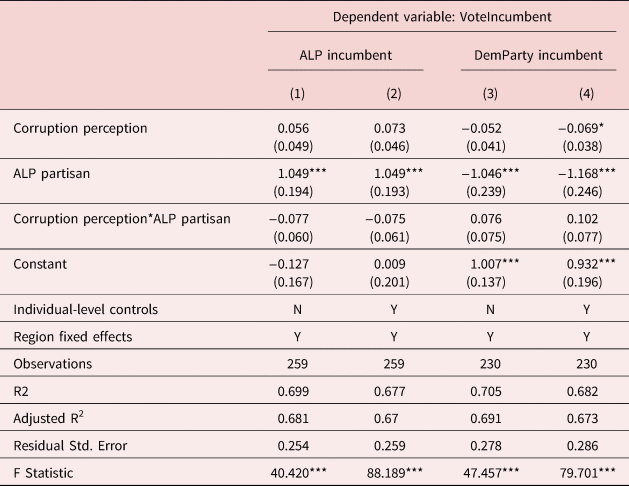

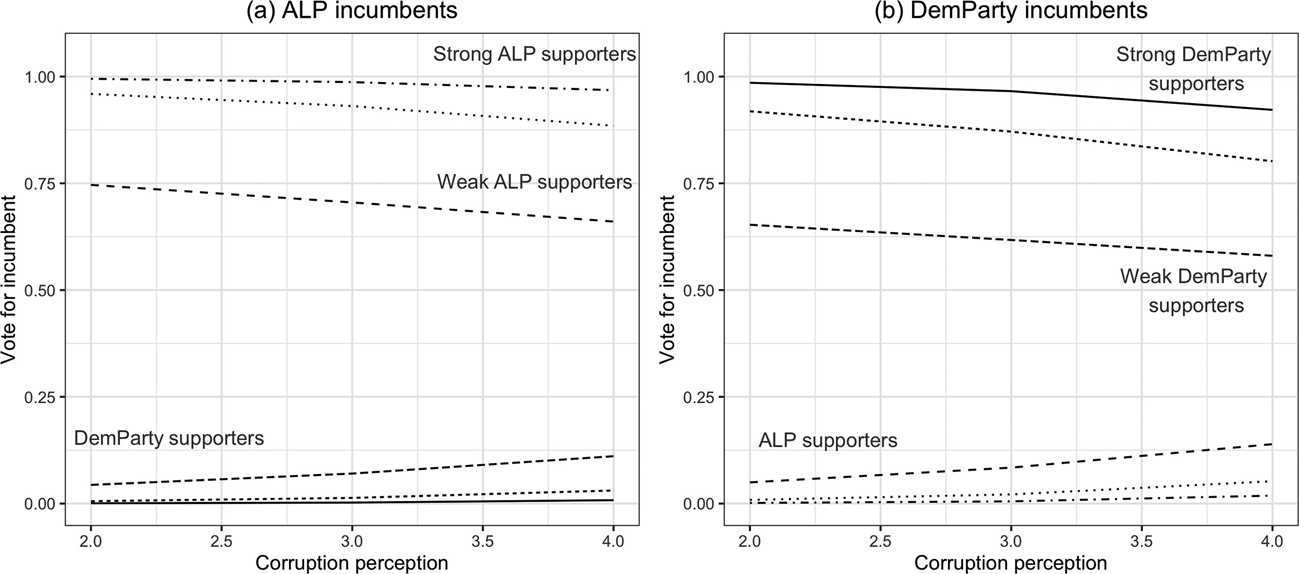

Empirical results from individual survey data analysis support the asymmetry hypothesis on copartisan bias. Table 3 shows differing patterns of corruption voting across party lines. In districts where the Democratic Party was incumbent (Models 3–4), I find results corresponding to conventional understanding of corruption voting: the consistent negative coefficients show that Democratic Party supporters chose to vote out copartisan incumbents when the perceived level of corruption was high. ALP supporters, on the other hand, show a distinctive pattern in copartisan corruption voting. In ALP incumbent districts (Models 1–2), ALP partisans did not meaningfully alter their voting behavior based on corruption perception. They maintained around 95 percent of support for the incumbents across different levels of corruption perception (see Figure 1). This consistently high support among ALP supporters contrasts the negative effect of corruption perception among DemParty supporters. The findings are robust after including individual-level control variables.

Figure 1. Copartisan bias in corruption voting: panels are from Models 1 and 3 in Table 3. Results for ALP supporters are in dashed lines and those for Democratic Party supporters are in solid lines.

Table 3. Corruption perception and voting for incumbents

Note: Models 1–2 include districts with authoritarian legacy party (ALP) incumbents and Models 3–4 includes districts with Democratic Party (DemParty) incumbents. Coefficients from OLS regression (*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01).

In order to better examine the main argument's emphasis on stronger partisan attachment among ALP supporters, Figure 2 plots the main effects across different levels of partisan attachment between ALP and Democratic Party supporters. The panels in Figure 2 show corresponding patterns to the findings in Table 3 and Figure 1: ALP supporters of strong and moderate partisan attachment maintain their copartisan support regardless of their corruption perception while Democratic partisans tend to withdraw their support when they have high corruption perception. The figure further contrasts the behaviors of strong partisans among ALP and Democratic partisans: whereas strong Democrats tend to vote away from corrupt copartisan candidates, strong ALP supporters maintain their support for copartisan candidates even when their corruption perception is high. Table A.2 in Appendix further demonstrates the lack of punishment for corruption among ALP supporters. While around 88–100 percent of Democratic partisans with a low perception of corruption voted for the incumbent, this proportion declines to 70–80 percent if their corruption perception is high. This low level of support is consistent across levels of partisan attachment. In contrast, ALP supporters retained around 96–100 percent of support for their copartisan incumbents regardless of their level of corruption perception or partisan attachment. Combined results corroborate that it is not just the level of partisan attachment but different types of partisanship that drive varying responses to the performance of incumbent politicians.

Figure 2. Copartisan bias in corruption voting across partisan attachment.

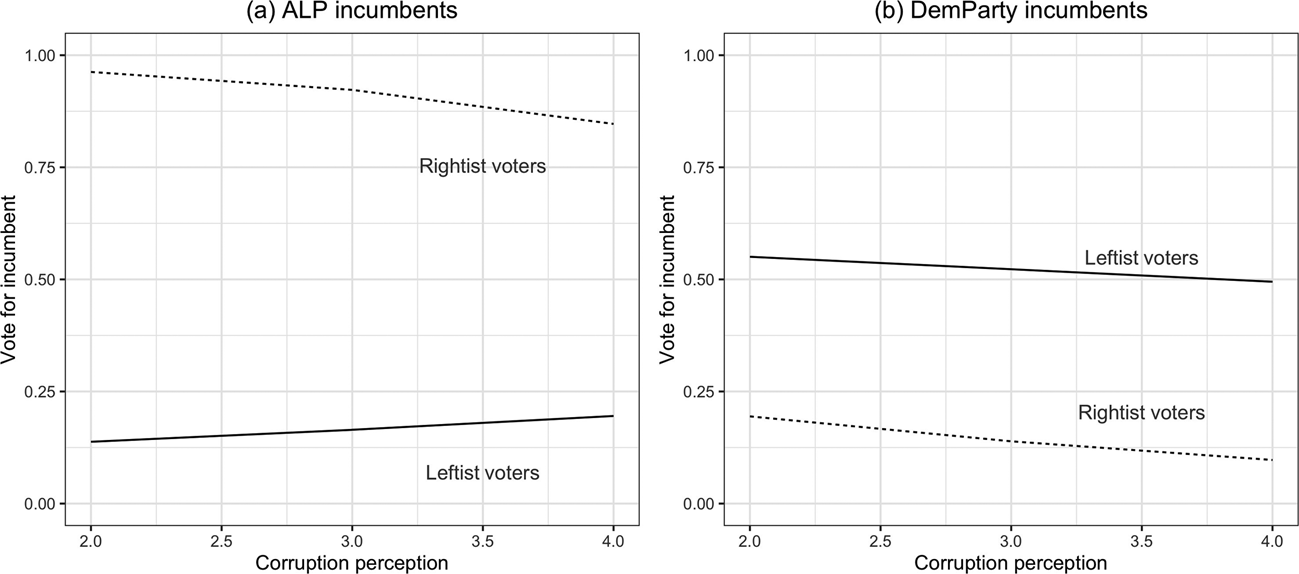

The preceding analyses examined ALP partisans as a special case of conservative voters who might have stronger partisan attachment due to their strong conservative ideology and affective partisanship stemming from authoritarian nostalgia. I further test this claim empirically by comparing the corruption voting behavior of ALP partisans and rightist voters using individual survey data. To do so, I mimic the analysis of Table 3 and Figure 1, but replacing the ALP partisan variable with a new variable classifying voters based on their ideological positions. I create a binary variable that codes respondents as 1 if they self-identify as rightist (self-reported ideology score greater than the third quartile) and 0 if they place themselves on the left (ideology score less than the first quartile). The expectation is that while we expect less punishment for corrupt incumbents from conservative voters due to their psychological rigidity, explicit authoritarian legacy partisans will be even more likely to turn a blind eye to copartisan incumbents due to their greater partisan attachment.

Results in Figure 3 suggest distinct patterns of corruption voting between ALP partisans and rightist voters. Rightist voters align with the conventional understanding of corruption voting and are more likely to vote out rightist politicians when voters’ perceived level of corruption is high (left panel). This pattern contrasts the findings in Figure 1 where ALP partisans maintained constant support for their copartisan incumbents. The combined results indicate the distinct voting patterns of ALP partisans originates in their stronger partisan attachment, compared to voters with right-wing conservative ideology.

Figure 3. Copartisan bias of leftist and rightist voters: panels are from regression analysis of voting for the incumbent. The main explanatory variables are voters’ left–right ideology and corruption perception. Results for rightist voters are in dashed lines and those for leftist voters are in solid lines.

While empirical results reveal a discrepancy in partisan bias among South Korean voters with data collection at the district and individual levels, additional analysis that employs a larger dataset or experimental data could provide additional evidence of this theory. District-level analysis finds support for the theoretical arguments, but the statistical findings from the main regression results bear limitations due to the small sample size. Empirical results from the individual-level analysis show that the district-level results are paralleled at the individual level, but the main regression coefficients are weakly significant. I employed the simulation-based test to account for the small sample issue with the district-level analysis and presented additional results in Table A.2 for the individual-level analysis. While these additional analyses increase confidence in the presence of asymmetric partisan bias, future work with additional data collection should bolster our understanding of the discrepancy in partisan voting behavior.

Conclusion

Voters acknowledge corruption as a valence issue impeding democracy. Despite this, when given an opportunity to throw the rascals out at elections, voters weigh the importance of corruption against other issues and in the end may choose to not hold politicians accountable for their malfeasance. Where previous work established how partisan bias and motivated reasoning makes voters less likely to change their voting behavior in response to copartisan politicians’ poor performance, this article expands the field by investigating partisan bias in the study of corruption voting and by examining a particular type of party, the authoritarian legacy party (ALP), and the lack of corruption voting among its partisans. Partisanship distorts individuals’ interpretation of reality, but this distortion occurs to varying degrees depending on which party you support.

Partisanship is now understood as a type of a social identity wherein individuals have a psychological attachment to their partisan group, leading them to develop favoritism towards copartisans and animosity towards outpartisans (Huddy, Mason, and Aarøe Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015). Yet the debate over whether partisan bias is equivalent across different parties is far from settled. The consistent empirical findings from South Korea delineated in this article increases confidence in the presence of asymmetric partisan bias in voters’ performance evaluation. Non-ALP partisans are more likely to withdraw support for corrupt politicians while ALP partisans are less likely to apply similar heuristics to corruption information.

The discernible effects of authoritarian legacy parties on voting behavior address the persistence of authoritarian legacies in post-authoritarian democracies. After an initial focus on institutional legacies of the authoritarian past (O'Donnell Reference O'Donnell1994; Grzymała-Busse Reference Grzymała-Busse2002; Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2017; Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Lust and Waldner Reference Lust, Waldner, Bermeo and Yashar2016), scholars have revealed the presence of authoritarian nostalgia and its effects on individual political attitudes (Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2017; Gherghina and Klymenko Reference Gherghina and Klymenko2012; Nadkarni and Shevchenko Reference Nadkarni and Shevchenko2004). They found that people with authoritarian nostalgia are less likely to support democratic values and more likely to positively evaluate the authoritarian past (Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2017; Seligson and Tucker Reference Seligson and Tucker2005). This article investigated the popular effects of authoritarian nostalgia when combined with partisan attachment to a particular former ruling party. Contrary to previous emphasis on the “break from the past” in studying the success of authoritarian successor parties (Grzymała-Busse Reference Grzymała-Busse2002; Slater and Wong Reference Slater, Wong, Loxton and Mainwaring2018), this article demonstrates that the past is often evoked in post-authoritarian democracies and that ALPs mobilize these sentiments for electoral success. This finding adds to the limited literature studying the partisan effects of authoritarian legacy parties on political behavior in post-authoritarian democracies.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2023.5