1. Introduction

The novelist Graham Greene first introduced the term ‘burnt out’ when he wrote about a fictional architect who could no longer find meaning in art or pleasure in life [Reference Greene1]. The term ‘burnout’ was introduced to the scientific literature in 1974 by an American psychologist Herbert J Freudenberger where he described burnout as a ‘state of mental and physical exhaustion caused by one’s professional life’ [Reference Freudenberger2]. Freudenberger defined it as something that related exclusively to frontline human service workers. Subsequently, Maslach and Jackson defined burnout as a psychological syndrome that occurs in professionals who work with other people in challenging situations that is characterised by (a) emotional exhaustion; feeling overburdened and depleted of emotional and physical resources, (b) depersonalisation; a negative and cynical attitude towards people, and (c) a diminished sense of personal accomplishment [Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter3, Reference Maslach and Jackson4]. Although, this definition of burnout remains most prominent in the literature other definitions of burnout have also been proposed [Reference Kristensen, Borritz, Villadsen and Christensen5]. Kirstensen et al. 2005 proposed that fatigue and exhaustion are the core feature of burnout but that depersonalisation is a coping strategy, while reduced personal accomplishment a consequence rather than a defining feature of burnout [Reference Kristensen, Borritz, Villadsen and Christensen5]. Demerouti and Bakker (2007), proposed that burnout was defined by two core dimensions (a) affective, physical and cognitive exhaustion and (b) disengagement from work [Reference Demerouti6]. An important development in this field has been an attempt by researchers to expand their understanding of burnout by looking at what could be considered its positive antithesis which has been defined as ‘work engagement’ [Reference Maslach and Leiter7, Reference Demerouti, Bakker, de Jonge, Janssen and Schaufeli8]. However, while some researchers consider engagement to be the opposite of burnout [Reference Maslach and Leiter7]. Others define engagement as a persistent, positive affective-motivational state of contentment that is characterised by the three components of vigour, dedication and absorption. In this view, work engagement is an independent and distinct concept, which is not the opposite of burnout [Reference Demerouti, Mostert and Bakker9].

Burnout has been found to be associated with job dissatisfaction, low organisational commitment, absenteeism, intention to leave the job, and turnover [Reference Maslach and Leiter7, Reference Schaufeli and Enzmann10]. Furthermore, there is considerable evidence that burnout has negative impacts on the physical and mental well-being of the individual worker [Reference Ahola, Väänänen, Koskinen, Kouvonen and Shirom11], the welfare and functioning of the team and organisation in which they work [Reference Bakker, Le Blanc and Schaufeli12, Reference Westman, Bakker, Roziner and Sonnentag13], and is associated with lower productivity and impaired quality of care provided to patients [Reference Demerouti, Bakker and Leiter14]. Factors particular to the mental health field have been proposed to make workers in this field more vulnerable to burnout [Reference Maslach and Leiter7]. These factors include stigma of the profession [Reference Rössler15], demanding therapeutic relationships [Reference Rössler15] and threats of violence from patients and patient suicide [Reference Rössler15, Reference Jovanović, Podlesek, Volpe, Barrett, Ferrari and Rojnic Kuzman16]. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and determinants of burnout in MHPs has not been conducted.

1.1. Aims of this study

The aim of this review is [Reference Greene1] to quantify the level of burnout in MHPs and [Reference Freudenberger2] to identify specific determinants of burnout in MHPs.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search

We used the PRISMA guidelines. A systematic search of MEDLINE/PubMed, PsychINFO/Ovid, Embase, CINAHL/EBSCO and Web of Science was conducted in May 2017 for original research published from 1st January 1997 until 31st December 2016. Relevant controlled vocabulary terms and free text terms related to burnout and MHPs were used to search each database. In all databases, the search was restricted to studies published in English. All studies had to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. The reference lists from articles and reviews were examined for any additional studies. The full search strategies for the individual databases can be found in Appendix 1.

2.1.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were [Reference Greene1]: the study examined the prevalence/ determinants of burnout [Reference Freudenberger2], the sample population was comprised of MHPs (including doctors, nurses, social workers, psychologists, occupational therapists, counsellors) working in mental health services [Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter3], the study had to be empirical and quantitative [Reference Maslach and Jackson4] the response rate was greater than 25% [Reference Kristensen, Borritz, Villadsen and Christensen5], the study sample was comprised of at least 50% MHPs [Reference Demerouti6], the study included at least 50 participants. The exclusion criteria was [Reference Greene1] the study did not use a validated measure of burnout.

2.1.2. Study selection, data extraction and assessment of study quality

After removing the duplicates, two investigators (KOC and DMN) reviewed study titles and abstracts for eligibility. If at least one of them considered an article as potentially eligible, the full texts were assessed by the same reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. Detailed information on the country, data source, study population, and results were extracted from each included study into a standardized spreadsheet by one author and checked by a second author (KOC and DMN). EndNote X7.3.1 (Thomas Reuters, New York, USA) was used to organize the identified articles.

Two investigators (KOC and DMN) independently assessed the risk of bias of each of the included studies. A score for quality, modified from the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), was used to assess the appropriateness of research design, recruitment strategy, response rate, representativeness of the sample, objectivity/reliability of outcome determination, power calculation provided, and appropriate statistical analyses (See Appendix 2). Score disagreements were resolved by consensus. An NOS score of 8 or more was considered ‘good,' a score of 5 or less was considered ‘poor.'

2.2. Data synthesis

The meta-analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, version 3 (Biostat Inc., NJ, USA). In light of expected differences in study sample and design, random-effects models were used to calculate the pooled means and prevalence. Heterogeneity across studies was tested using Q statistics [Reference Cochran17], and the I2 [Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman18]. Results from studies grouped according to pre-specified study-level characteristics were compared using subgroup analyses (for MBI-HSS High EE/DP/PA ‘cut off’ score, geographical location and NOS) and random effects meta-regression (for age, sex, study size and professional background of participants). To address the issue of publication bias, we examined funnel plots [Reference Egger and Smith19], and used the Eggers Test [Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder20].

3. Results

3.1. Search outcome

The electronic literature search identified 1348 unique citations. Based on a review of article titles and abstracts 1262 citations were excluded. After full-text review 62 articles remained (See Fig. 1 for PRISMA flow diagram). The features of the identified studies are summarised in Table 1.

3.2. Study population and study design

Studies conducted across 33 different countries were identified. The vast majority of studies were cross-sectional (N = 57) and multi-site (N = 47). However, five studies had a longitudinal design with follow-up times varying between six months [Reference Rogala, Shoji, Luszczynska, Kuna, Yeager and Benight67, Reference Shoji, Lesnierowska, Smoktunowicz, Bock, Luszczynska and Benight68] and five years [Reference Kumar, Hatcher, Dutu, Fischer and Ma’u50]. Self-reported questionnaires were utilised in every study. The number of respondents ranged from 60 [Reference Galeazzi, Delmonte, Fakhoury and Priebe36] to 2258 [Reference Johnson, Osborn, Araya, Wearn, Paul and Stafford45]. The mean study size was 370.61 (SD 457.77), the median was 195. In most studies, female respondents were over-represented. Mean age of respondents ranged from 30.9 years [Reference Hamaideh39] to 51.6 years old [Reference Rupert and Morgan71] and the response rate varied between 26% [Reference Jovanović, Podlesek, Volpe, Barrett, Ferrari and Rojnic Kuzman16] and 100% [Reference Chakraborty, Chatterjee and Chaudhury28]. The minority of studies (N = 11) examined burnout in the inpatient setting exclusively. The rest examined burnout in community settings or a mix of community and inpatient settings.

Most studies examined the prevalence and correlates of burnout in several different MHP groups (N = 31). Data on burnout in nursing staff was gathered in 30 studies, in doctors in 17 studies, in psychologists in ten studies, in occupational therapists in eight studies, in social workers in 12 studies. Although the data on individual professional groups was not reported in each of these studies.

3.3. Quality of studies

On the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) 15 of the studies rated as being of good quality (score ≥8) 41 studies rated as being of moderate quality (score 6–7) and six studies rated as being of poor quality (score ≤5) [Reference Galeazzi, Delmonte, Fakhoury and Priebe36] (See Table 1)

3.4. Measurement of burnout

Eight validated measures of burnout are cited in the literature between 1997 and 2017. These are the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [Reference Maslach, Jackson and Leiter83] (n = 54), the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) [Reference Demerouti6] (n = 2), the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) [Reference Kristensen, Borritz, Villadsen and Christensen5](n = 3), Pines Burnout Measure (n = 3), the Psychologists Burnout Inventory (n = 2), the Organisational Social Context Scale (OSCS) [Reference Glisson, Landsverk, Schoenwald, Kelleher, Hoagwood and Mayberg84](n = 1), the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL III) [Reference Stamm85] (n = 1) and the Children’s Services Survey- emotional exhaustion subscale (n = 1). Five studies utilised more than one validated measure of burnout.

Fig. 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

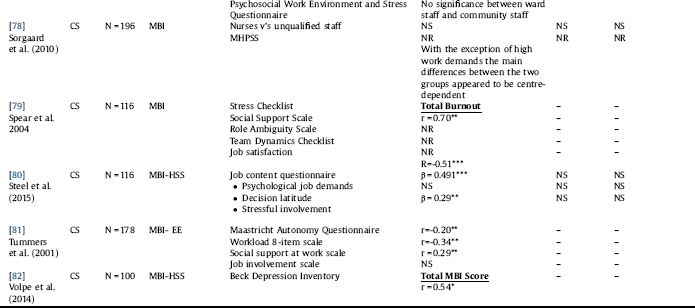

Table 1 Overview of the selected studies, the basic characteristics and results.

NS not significant, NR Not reported, * p < 0.05, **p <0.01, ***p < 0.001.

MBI-HSS Maslach Burnout Inventory Health Services Survey, MBI-GS Maslach Burnout Inventory General Survey, CBI Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, OLBI Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, ProQOL Professional Quality of Life.

The MBI-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) was utilised by 50 studies while the MBI-General Survey (MBI-GS) was utilised by four studies (See Table 2). The original MBI-HSS was developed for the human services field and included 22 items; emotional exhaustion (MBI-EE nine items), depersonalisation (MBI-DP five items), personal accomplishment (MBI-PA eight items). The scores for each of the three factors are totalled separately and can be coded as low, average or high using cut-off scores defined in the MBI Manual [Reference Maslach, Jackson and Leiter83]. See Appendix 3 for information on the cut-off scores for MHPs. Reliability and validity of the MBI-HSS have been established across a wide range of countries and professional settings including in the mental health field [Reference Maslach, Jackson and Leiter83, Reference Poghosyan, Aiken and Sloane86–Reference Gil-Monte89]. Maslach and Jackson later adopted a measure suitable for use in any professional context the MBI-General Survey (MBI- GS). This MBI-GS contains three scales that parallel those of the original MBI: Exhaustion (EX), Cynicism (CY) and Personal Efficacy (PE). This scale has been found to be reliable and valid across multiple occupational and cultural settings [Reference Schutte, Toppinen, Kalimo and Schaufeli90].

3.5. Prevalence of burnout in MHPs

3.5.1. Mean score on MBI subscales

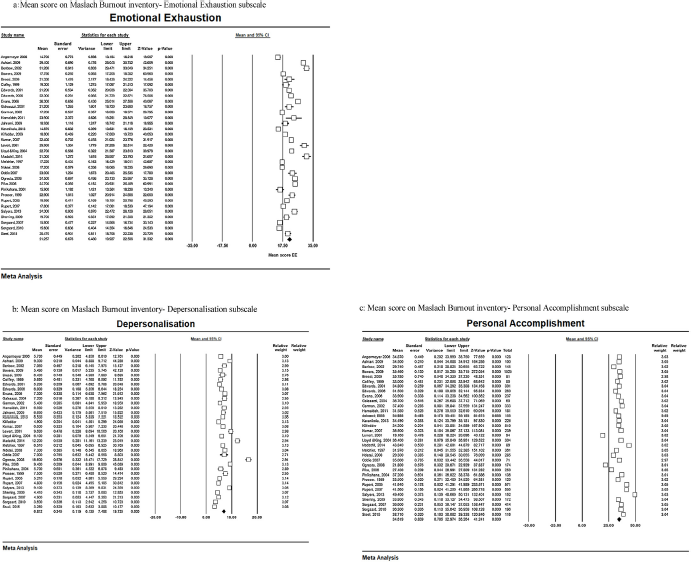

Thirty-nine studies reported means and standard deviations for the different dimensions of burnout while five studies reported means but no standard deviations. Only studies, which utilised the MBI-HSS, and the MBI-GS were included in the meta-analysis (33 studies). The total sample of MHPs was n = 9409. The overall random-effects estimate of the mean for the MBI-EE was 21.25 (95% CI 19.92, 22.58, MBI-DP was 6.82 (95% CI 6.13, 7.48) and MBI-PA was 34.61 (95% CI 32.97, 41, 24). There was significant evidence of between-study heterogeneity (EE: Q 1282.8, df 36, p < 0.001; I2 = 97.3%, DP: Q 1485.0, df 33, p < 0.001; I2 = 97.8%, PA: Q 5577, df 34, p < 0.001, I2 = 99.39%). See Fig. 2 for forest plots. Sensitivity analyses, in which the meta-analysis was serially repeated after exclusion of each study, demonstrated that no individual study affected the overall pooled mean by more than 0.50 point (See Appendix 4). To further characterise the range of MBI subscale mean estimates, some pre-defined subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses were conducted.

When only studies rated ‘good’ on NOS (M8) were considered, the pooled mean estimates decreased for EE to 17.54 (95%CI 16.27, 18.02), with reduced heterogeneity (I2 = 73%, p < 0.001), for DP to 5.19 (95%CI 5.05, 5.34) with reduced heterogeneity (I2 = 83%, p < 0.001) and for PA to 37.81 (95% CI 37.37, 37.96, I2 = 96.3%, P < 0.001) (Appendix 5). When the studies were analysed in subgroups according to the geographical region in which they were conducted there were significant differences noted across the PA mean estimates (test for subgroup differences Q 59.17, p < 0.001). When only studies from North America were considered, the pooled mean estimates for PA increased to 41.74 (95% CI 41.52, 41.93) (I2 = 99%, p < 0.001), whereas when only studies from Europe were considered, the pooled mean estimate for PA reduced to 32.49 (95% CI 32.29, 32.69) (I2 = 99%, p < 0.001) (Appendix 5).

Meta regression analyses indicated that age was associated with increased PA, (slope = 0.36 points increase on the PA scale per 1-year increase in average age [95% CI 0.11 to 0.62]; Q = 6.52, p = 0.01; R2 = 0.52). Estimates of the pooled mean of EE was found to vary with study size (slope = -0.01 point reduction in the EE mean, per increase of n = 1 [95% CI, -0.01 to -0.0004]; Q = 4.53, p = 0.03; R2 = 0.03]. Estimates of the pooled mean EE and DP were found to vary with the percentage of nurses in the study (slope= −0.02 point decrease in EE mean, per 1% increase in nurses in the sample [95% CI -0.04 to 0.002]; Q = 4.8, p = 0.02, R2 = 0.17), (slope = – 0.01 decrease in DP mean per 1% increase in nurses in the sample [95% CI -0.02 to -0.003]; Q = 7.01, p = 0.008, R2 = 0.27]. The percentage of psychologists in a study was also found to be associated with decreased DP and increased PA scores (slope = -0.004 decrease in DP score with each increase in 1% of psychologists in the sample [95% CI -0.08 to 0.00]; Q = 3.84, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.66), (slope = 0.01 increase in PA score with each increase in 1% of psychologists in the sample [95% CI 0.011 to 0.013] Q = 622.8, R2 = 1). See Appendix 6.

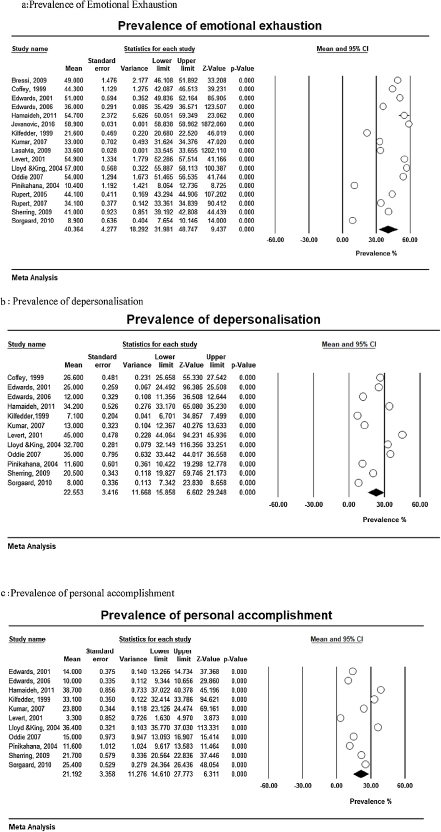

3.5.2. Prevalence of ‘high’ rates on burnout subscales

The meta-analytic pooling of the prevalence estimates of ‘high’ rates of emotional exhaustion, ‘high’ rates of depersonalisation and ‘low’ rates of personal accomplishment were calculated for studies utilising the MBI-HSS (15 studies) and MBI-GS (2 studies). Where the ‘cut off’ was unclear or was not in line with those recommended by the MBI scale authors, this was stated in Table 1 and the study was not included in the meta-analysis. Seventeen studies reported on ‘high’ rates for emotional exhaustion (n = 7935) and fourteen studies reported on ‘high’ rates for depersonalisation/ cynicism and personal accomplishment / personal efficacy (n = 7469). The pooled prevalence indicated that 40% (CI 31%–48%, Q = 4874, df = 13, p < 0.001, I2 = 99.7) exceeded the ‘high’ cut-off for emotional exhaustion, 22% (CI 15%–29%, Q = 64710, p < 0.001, I2 = 99.9) exceeded ‘high’ cut-off for depersonalisation / cynicism and 19% (CI 13%–25%, Q = 2605, p < 0.001, I2 = 99.7) exceeded cut-off for low levels of personal accomplishment/ personal efficacy. See Fig. 3. There was significant evidence of between-study heterogeneity, and subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses were conducted to explore this.

Studies included in this meta-analysis applied two different ‘cut-off’ points on the MBI-HSS when determining prevalence rates. Eleven studies applied the cut-off specified for MHPs (EE > 21, DP > 8, PA < 28) [Reference Bressi, Porcellana, Gambini, Madia, Muffatti and Peirone27, Reference Coffey29, Reference Edwards, Burnard, Coyle, Fothergill and Hannigan31, Reference Edwards, Burnard, Hannigan, Cooper, Adams and Juggessur32, Reference Hamaideh39, Reference Levert, Lucas and Ortlepp53, Reference Oddie and Ousley58, Reference Pinikahana and Happell63, Reference Rupert and Kent70, Reference Sherring and Knight74], three studies utilised the cut-offs for other health professionals (EE 27, εDP 11, PA δ35) [Reference Kilfedder, Power and Wells48, Reference Kumar, Fischer, Robinson, Hatcher and Bhagat49, Reference Sorgaard, Ryan and Dawson78]. A subgroup analysis was conducted to investigate the extent the use of two different cut-offs points was contributing to the between-study heterogeneity. The pooled prevalence of the EE > 21 cut-off group (n = 2542) was estimated at 44% (95% CI = 38%–49%) and for the EEε26 cut-off group (n = 945) was estimated at 21% (95% CI = 8%–33%). This was a statistically significant difference between the two groups (Z 13.46, p < 0.001). The pooled prevalence of the DP > 8 group (n = 1735) was estimated at 26% (95% CI = 20%–33%) and the pooled prevalence of the DPε11 (n = 945) group was 9% (95% CI = 5%–12%), a statistically significant difference (Z 10.29, p < 0.001). The pooled prevalence of the PA < 28 group (n = 1519) was estimated to be 18% (95% CI = 9%–28%) and for the PA δ35 group (n = 945) was estimated to be 27% (95% CI = 21%–33%. This difference was also statistically significant (Z 6.26, p < 0.001). See Appendix 7. A meta-regression analysis found that more than 50% of the EE between-study heterogeneity and more than 40% DP and PA between-study heterogeneity may be explained by the use of the two different MBI-HSS cut off scores (EE coefficient = 25.04, 95% CI = 14.8–35.3, p < 0.001, R2=0.52; DP coefficient = 16.86, 95% CI 5.66–28.06, P < 0.001, R2 = 0.44; PA coefficient = 26.23, 95% ci 20.37, 32.08, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.44).

3.6. Publication bias

Inspection of the funnel plots demonstrated that studies were distributed symmetrically. The Eggers test was not significant for bias for the means/ prevalence of emotional exhaustion (t = 1.43, df = 31, p = 0.08) depersonalisation (t = 1.94, df = 33 p = 0.06) or professional accomplishment (t = 1.37, df = 31, p = 0.10) (See Appendix 8).

Table 2 Determinants of Burnout in Mental Health Professionals.

NS not significant, NR Not reported, * p < 0.05, **p <0.01, ***p < 0.001, MBI-HSS Maslach Burnout Inventory Health Services Survey, MBI-GS Maslach Burnout Inventory General Survey, CBI Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, OLBI Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, ProQOL professional quality of life. EE Emotional Exhaustion, DP Depersonalisation, PA Personal Accomplishment, Ex Emotional Exhaustion, Cyn Cynicism, PE Personal Efficacy. BO Burnout. GHQ-12 General Health Questionnaire-12, MLQ- X4 Multifactor Leader Questionnaire- X4 CMHN Community Mental Health Nurses, Psych Psychiatrists, SW Social workers, CMHT Community Mental Health Teams, AOT Assertive Outreach Team, CRT Crisis Resolution Team.

3.7. Determinants of burnout in MHPs

Fifty-nine studies were included in the narrative review of determinants. For this review, we categorised these determinants in terms of ‘individual’ factors and ‘work-related’ factors [Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter3]. It was not possible to synthesise these results utilising meta-analytic techniques due to the variation in how determinants were assessed, and results reported. The studies and associated determinants are summarised in Table 2.

3.7.1. Individual factors

A negative correlation between age and depersonalisation was reported in eight studies [Reference Jovanović, Podlesek, Volpe, Barrett, Ferrari and Rojnic Kuzman16, Reference Benbow and Jolley23–Reference Bowers, Allan, Simpson, Jones and Whittington26, Reference Chakraborty, Chatterjee and Chaudhury28, Reference Johnson, Osborn, Araya, Wearn, Paul and Stafford45, Reference Lloyd and King52, Reference Rupert and Kent70, Reference Rupert and Morgan71]. While, two studies reported a positive relationship between age and depersonalisation [Reference Jeanneau and Armelius44, Reference Piko62]. A negative correlation between age and emotional exhaustion was reported by five studies [Reference Bowers, Allan, Simpson, Jones and Whittington26, Reference Chakraborty, Chatterjee and Chaudhury28, Reference Johnson, Osborn, Araya, Wearn, Paul and Stafford45, Reference Rupert and Kent70, Reference Rupert and Morgan71] and four studies reported a positive relationship between age and rating higher on the personal accomplishment sub-scale [Reference Blau, Tatum and Ward Goldberg25, Reference Hamaideh39, Reference Melchior, van den Berg, Halfens, Huyer Abu-Saad, Philipsen and Gassman55, Reference Rupert and Kent70]. The findings on the relationship between gender and burnout dimensions were inconsistent. No consistent relationship between the length of service and burnout was found in the studies identified in this review

3.7.2. Work-related factors

3.7.2.1. Workload

Increased workload/ high caseloads were found consistently by the studies in this review to be associated with higher rates of burnout [Reference Jovanović, Podlesek, Volpe, Barrett, Ferrari and Rojnic Kuzman16, Reference Angermeyer, Bull, Bernert, Dietrich and Kopf21, Reference Evans, Huxley, Gately, Webber, Mears and Pajak33, Reference Galeazzi, Delmonte, Fakhoury and Priebe36, Reference Hamaideh39, Reference Kumar, Hatcher, Dutu, Fischer and Ma’u50, Reference Lasalvia, Bonetto, Bertani, Bissoli, Cristofalo and Marrella51, Reference Levert, Lucas and Ortlepp53, Reference Ndetei, Pizzo, Maru, Ongecha, Khasakhala and Mutiso56, Reference Prosser, Johnson, Kuipers, Szmukler, Bebbington and Thornicroft65, Reference Tummers, Janssen, Landeweerd and Houkes81].

3.7.2.2. Job control

A sense of autonomy at work and perceived capacity to influence decisions that affect work was consistently reported by the studies identified in this review to be associated with lower rates of burnout, particularly lower rates of emotional exhaustion and increased rates of professional accomplishment [Reference Garman, Corrigan and Morris35, Reference Johnson, Osborn, Araya, Wearn, Paul and Stafford45, Reference Madathil, Heck and Schuldberg54, Reference Melchior, van den Berg, Halfens, Huyer Abu-Saad, Philipsen and Gassman55, Reference Rupert and Kent70, Reference Rupert and Morgan71, Reference Sherring and Knight74, Reference Steel, Macdonald, Schröder and Mellor-Clark80, Reference Tummers, Janssen, Landeweerd and Houkes81].

3.7.2.3. Community

Community relates to the on-going relationships that employees have with other people on the job. Role conflict was found in this review to be associated with increased rates of emotional exhaustion [Reference Kilfedder, Power and Wells48, Reference Levert, Lucas and Ortlepp53, Reference Piko62], role ambiguity associated with increased emotional exhaustion [Reference Kilfedder, Power and Wells48, Reference Levert, Lucas and Ortlepp53] and role clarity was associated with higher rates of personal accomplishment [Reference Green, Albanese, Shapiro and Aarons38]. Johnson et al. 2012 in their large sample of MHPs in the UK found that support from colleagues and managers was associated with reduced emotional strain and increased work engagement [Reference Johnson, Osborn, Araya, Wearn, Paul and Stafford45]. Lack of /inadequate clinical supervision was associated with increased risk of burnout in three studies [Reference Jovanović, Podlesek, Volpe, Barrett, Ferrari and Rojnic Kuzman16, Reference Edwards, Burnard, Hannigan, Cooper, Adams and Juggessur32, Reference Sherring and Knight74]. In a sample of 189 community mental health nurses, Edwards et al. [Reference Edwards, Burnard, Coyle, Fothergill and Hannigan31] demonstrated that higher scores on the Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale were associated with lower levels of measured burnout (EE: r=-0.148, p < 0.05, DP r=-0.22, p = 0.03) [Reference Edwards, Burnard, Hannigan, Cooper, Adams and Juggessur32]. Furthermore, Sherring & Knight (2009) reported that in a population of 172 nurses those who reported a lesser quantity (F = 4.25, p = 0.001) and or perceived inadequacy of clinical supervision (F = 7.63, p < 0.001) reported higher rates of emotional exhaustion. Fairness in how staff feel they are treated and a sense of being rewarded for work was identified as being important in protecting against the development of burnout [Reference Ndetei, Pizzo, Maru, Ongecha, Khasakhala and Mutiso56, Reference Ogresta, Rusac and Zorec59].

3.7.2.4. Work setting

In a longitudinal study, comparing levels of burnout and sources of stress among the community and acute ward staff in six European countries Sorgaard et al. 2007 (n = 414) found that burnout was not a serious problem among community or ward staff in this study at baseline, six months or 12 months [Reference Sorgaard, Ryan and Dawson78]. However, they did find that rates of emotional exhaustion were higher in community staff (EE mean 18.31 +/- 10.5) when compared to staff based on inpatient units (EE mean 15.8 +/- 9.74) and that the variable that primarily distinguished between ward staff and community staff was job control. Furthermore, although the staff in the community reported a greater sense of control, they also reported higher work demands. Johnson et al. 2012 reported significant differences in work demand and job control described by staff working in different parts of the mental health service [Reference Johnson, Osborn, Araya, Wearn, Paul and Stafford45]. Staff working in community mental health teams reported the highest level of work demand (Mean 3.36 (SD 1.03), max score 5.0) while staff working staff working on rehabilitation wards reported the lowest level (Mean 2.47 (SD 0.94)). Conversely, staff in community mental health teams reported the highest level of job control (Mean 3.65 (SD 0.76), max score 5.0) while those working on acute general wards reported the lowest level (Mean 2.99 (SD 0.89)). Furthermore, emotional exhaustion was significantly higher among acute general ward (EE mean 21.1, SD 12.7) and community mental health team staff (EE mean 23.8, SD 11.0) when compared to other service types (F = 8.87, p < 0.0005). Nelson et al. 2009 (n = 433) assessed and compared the burnout levels of crisis resolution teams with assertive outreach and community mental health teams utilising a multicentre cross-sectional survey in England [Reference Nelson, Johnson and Bebbington57]. This study found that staff on crisis resolution and assertive outreach teams reported significantly higher sense of personal accomplishment than staff working in community mental health teams (p=0.0005). Nelson et al. 2009 proposed that although the demands of working in a crisis resolution team are likely to be high, these may be mitigated by the sense of autonomy staff report and the benefit of working in a cohesive team [Reference Nelson, Johnson and Bebbington57]. Billings et al. 2003 (n = 301) compared satisfaction and burnout between assertive outreach teams and community mental health teams in London [Reference Billings, Johnson, Bebbington, Greaves, Priebe and Muijen24]. They found that staff on the assertive outreach team reported lower rates of depersonalisation (r=-1.7, p = 0.01) and higher rates of personal accomplishment (r = 1.8 p = 0.01) compared to staff on the community mental health teams.

Fig. 2. Forrest Plots of mean scores on Maslach Burnout Inventory. a Mean score on Maslach Burnout inventory- Emotional Exhaustion subscale. b Mean score on Maslach Burnout inventory- Depersonalisation subscale. c: Mean score on Maslach Burnout inventory- Personal Accomplishment subscale.

3.7.2.5. Professional background

Six studies reported on associations between burnout and MHPs professional background [Reference Billings, Johnson, Bebbington, Greaves, Priebe and Muijen24, Reference Galeazzi, Delmonte, Fakhoury and Priebe36, Reference Johnson, Osborn, Araya, Wearn, Paul and Stafford45, Reference Lasalvia, Bonetto, Bertani, Bissoli, Cristofalo and Marrella51, Reference Nelson, Johnson and Bebbington57, Reference Onyett, Pillinger and Muijen60, Reference Prosser, Johnson, Kuipers, Dunn, Szmukler and Reid66]. Five of these studies were completed in the UK. Johnson et al. 2012 reported that in their large sample of MHPs (n = 2258) social workers were significantly more likely than other MHP’s to report high rates of emotional exhaustion (F = 6.65, p < 0.001). In a longitudinal study, Prosser et al. 1999 reported higher rates of emotional exhaustion in social workers (β = 13.32, p < 0.01) and nurses (β = 4.03, p < 0.05) and lower rates of depersonalisation in psychologists (β=-3.22, p < 0.01) [Reference Johnson, Osborn, Araya, Wearn, Paul and Stafford45, Reference Prosser, Johnson, Kuipers, Szmukler, Bebbington and Thornicroft65]. Billings et al. 2003 and Nelson et al. 2009 also reported lower levels of depersonalisation in psychologists when compared to other MHPs (r=-3.2, p < 0.001; p < 0.05) [Reference Billings, Johnson, Bebbington, Greaves, Priebe and Muijen24, Reference Nelson, Johnson and Bebbington57].

Fig. 3. Prevalence of burnout as rated on Maslach Burnout Inventory. a Prevalence of Emotional Exhaustion. b Prevalence of depersonalisation. c Prevalence of personal accomplishment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key findings

This review included data on prevalence and determinants of burnout in MHPs from 62 studies, across 33 different countries. It is the first systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic in MHPs.

The overall estimate of the means for the burnout dimensions as rated on the MBI-HSS were 21.11 for emotional exhaustion, 6.76 for depersonalisation and 34.60 for depersonalisation. These means indicate that the average MHP has a ‘high’ level of emotional exhaustion, a ‘moderate’ level of depersonalisation but retains a ‘high’ level of personal accomplishment. These findings suggest that MHPs may still feel competent despite feeling exhausted, overextended, depleted and disconnected. The prevalence estimates for emotional exhaustion was 40% (range, 8%–59%), for depersonalisation was 22% (range, 8%–65%) and for low sense of personal accomplishment were 19% (range 3%–38%). Given that emotional exhaustion is typically considered the core dimension of burnout, this review indicates that 40% of the respondents in the selected studies suffered from professional burnout [Reference Maslach and Leiter7].

The systematic review of determinants found a reasonably consistent relationship between increasing age and increased risk of depersonalisation but also an increased sense of personal accomplishment. The relationship between increased workload and increased rates of burnout was consistent across the studies identified. This relationship arose as a particular issue for those working in general community teams more than those working in specialist teams, e.g., assertive outreach teams, crisis teams, forensic settings. A sense of autonomy and perceived capacity to influence decisions at work were associated with lower rates of burnout. The data from the present study suggests that staff working in general adult in-patient settings report a lower sense of autonomy at work, while staff in the community teams and particularly in the specialist teams reported a greater sense of autonomy and associated personal accomplishment. The data identified in this review indicates that when relationships at work are characterised by role conflict, role ambiguity, and unresolved conflict, there is a higher risk of burnout. Clinical supervision, a sense of being treated fairly and of receiving fair reward for one’s work appears to be protective. There was some data suggesting that social workers, working in the UK were at higher risk of burnout in comparison to other MHPs. Whereas, there was data suggesting that psychologists in the UK may be at lower risk of depersonalisation when compared to other MHPs.

4.2. Comparison with previous literature

The pooled estimates of respondents exceeding the ‘high’ cut-offs for the different dimensions of burnout are double those seen in the general population [Reference Lindblom, Linton, Fedeli and Bryngelsson92] and considerably higher than those reported in a systematic review of burnout in emergency nurses in which 26% reported high rates of emotional exhaustion [Reference Adriaenssens, De Gucht and Maes93, Reference Gómez-Urquiza, Aneas-López, Fuente-Solana, Albendín-García, Díaz-Rodríguez and Fuente94], and a meta-analysis of health professionals working in palliative care in which 17.5% reported high rates of emotional exhaustion, 6.5% reported high levels of depersonalisation and 19.5% reported low levels of personal accomplishment [Reference Parola, Coelho, Cardoso, Sandgren and Apóstolo95]. The rates of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation are also similar to those reported in a meta-analysis of burnout in cancer professionals, which reported high rates of emotional exhaustion in 36%, high rates of depersonalisation in 34%. However, the rates of low personal accomplishment in this meta-analysis of cancer professionals were reported as 25%, which is considerably higher than the 18% reported in this meta-analysis of MHPs [Reference Trufelli, Bensi, Garcia, Narahara, Abrão and Diniz96].

Consistent with previous reviews on this topic we did find significant relationships between workload, role conflict, lack of job control and burnout [Reference Maslach and Leiter7, Reference Rössler15, Reference Paris and Hoge88, Reference Fothergill, Edwards and Burnard97–Reference Kumar99]. The findings that community staff are at higher risk of burnout is consistent with a literature review of burnout in community mental health nurses [Reference Edwards, Burnard, Coyle, Fothergill and Hannigan100].

4.3. Limitations

This study has important limitations. Firstly, the levels of heterogeneity identified across studies in this review were high. However, meta-analyses of prevalence studies often report high levels of heterogeneity and published meta-analyses on the prevalence of burnout in other health professionals report similarly high levels of heterogeneity [Reference Parola, Coelho, Cardoso, Sandgren and Apóstolo95, Reference Trufelli, Bensi, Garcia, Narahara, Abrão and Diniz96, Reference Gómez-Urquiza, De la Fuente-Solana, Albendín-García, Vargas-Pecino, Ortega-Campos and Cañadas-De la Fuente101]. Some of the variance in this study was explained by the use of different cut-offs for ‘caseness’ on the MBI-HSS subscales, differences in the quality of the studies as rated on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, the average age of study participants, geographical region in which studies were conducted, sample sizes and % of nurses/psychologists in the studies. However, work-related factors such as high caseload, poor team functioning, and lack of job control make MHPs more vulnerable to developing burnout. While these factors may be perpetuated by features common across the field of psychiatry; national health service characteristics and then local organisational factors are likely to be more critical to the work-related experience of MHPs and underlie their vulnerability to burnout. As such, some variation in the reported prevalence of the burnout phenomenon across countries and the world is unsurprising.

Secondly, although doctors, nurses, and psychologists were reasonably well represented in the studies identified, few studies reported individual data for other MHPs. Studies which reported on differences between rates of burnout in MHP’s were primarily UK samples and given there are differences in how MHP’s work in different countries these findings may not represent the experience in other countries and service delivery models. Thirdly, several conceptual models of burnout emphasise the need for a good person-environment fit to prevent burnout. However, the majority of studies identified only measured some work stressors and some outcomes, without taking into account the perception of the stressor by the MHP. These limitations mean that only a small part of the variance can be explained, interrelationships between determinants cannot be adequately investigated, results from different studies cannot be easily compared and causal relationships between determinants and outcomes cannot be made.

5. Conclusion

Burnout rates are high in MHPs, with the summary estimate of the prevalence of emotional exhaustion being 40%. The present systematic review indicates that interventions to prevent and reduce burnout should focus on the promotion of professional autonomy, manageable caseloads, the development of good team function and the provision of quality clinical supervision to all MHPs.

Burnout rates are high in MHPs, with the summary estimate of the prevalence of emotional exhaustion being 40%. The present systematic review indicates that interventions to prevent and reduce burnout should focus on the promotion of professional autonomy, manageable caseloads, the development of good team function and the provision of quality clinical supervision to all MHPs.

Author contributions

KOC, DMN and SP designed the study. KOC and DMN completed the data collection, analysis and interpretation. KOC drafted the article. DMN and SP revised the article. KOC, DMN and SP approved the final draft of the article.

Conflict of interest statement

KOC, DMN and SP have no competing interest to declare.

Role of funding source

This research did not receive funding from any specific grant from funding agencies in public, commercial, or not for profit sectors.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.06.003.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.