Introduction

Eurypterids are rare components of Mississippian faunal assemblages. Only three families are known, although they belong to both suborders, the Eurypterina and the Stylonurina (Table 1). These same higher taxa persist until the final extinction of the eurypterids during the Permian, with overall diversity remaining low (Lamsdell et al., Reference Lamsdell, Braddy and Tetlie2010; Lamsdell and Selden, Reference Lamsdell and Selden2017). In late Paleozoic strata, eurypterids are found only in freshwater environments (Lamsdell and Selden, Reference Lamsdell and Selden2017).

Table 1. Mississippian Eurypterids. Classification of Dunlop et al. (Reference Dunlop, Penney and Jekel2020). Within genera, given in stratigraphic order (oldest to youngest). Note: Hibbertopterus(?) hibernicus from Kiltorcan, Ireland, may be latest Upper Devonian, rather than Tournaisian in age (Jarvis, Reference Jarvis1990).

The geographic range of Mississippian eurypterids is also limited (Tetlie, Reference Tetlie2007). More than half of the Mississippian eurypterids come from Visean and Serpukhovian units in Scotland and were described in detail by Charles Waterston (Waterston, Reference Waterston1957, Reference Waterston1968; Størmer and Waterston, Reference Waterston1968). Additional early Carboniferous eurypterid localities in Scotland were mentioned but not described by Smithson et al. (Reference Smithson, Wood, Marshall and Clack2012). Outside of Scotland, only Cyrtoctenus wittebergensis Waterston, Oelofsen, and Oosthuizen, Reference Waterston, Oelofsen and Oosthuizen1985, from the Tournaisian of South Africa is well known. Here, we describe the first Mississippian eurypterids from North America and only the fourth eurypterid occurrence known from the Tournaisian.

Geological setting

The Price Formation is a Lower Mississippian unit exposed in a narrow outcrop belt in the Appalachians from Virginia northeast into Pennsylvania (Kammer and Bjerstedt, Reference Kammer and Bjerstedt1986; Bjerstedt and Kammer, Reference Bjerstedt and Kammer1988; Nolde, Reference Nolde1994). It is interpreted as a southwest-prograding deltaic complex, comprising a complex of marine, delta front, and coastal alluvial facies, including coal-producing swamp deposits (Kreisa and Bambach, Reference Kreisa and Bambach1973; Bjerstedt and Kammer, Reference Bjerstedt and Kammer1988). In Virginia, the upper part of the Price, which contains the deltaic sequence, is dated as Kinderhookian to lower Osagean (Kammer and Bjerstedt, Reference Kammer and Bjerstedt1986; Bjerstedt and Kammer, Reference Bjerstedt and Kammer1988; Gensel, Reference Gensel1988; Gensel and Pigg, Reference Gensel and Pigg2010) or solely Osagean (Nolde, Reference Nolde1994), which corresponds to Tournaisian. Two localities in the Virginia portion of the outcrop belt (Brush Mountain-Little Walker Mountain outcrop belt; Bjerstedt and Kammer, 1998, fig. 2) have yielded specimens of eurypterids from shales.

Locality 1: Coal Bank Hollow

About 100 m of the Price Formation is exposed along U.S. 460, between Coal Bank Hollow Road and County Route 648 (Brown, Reference Brown1983), Brush Mountain, 3.2 km north of Blacksburg, Montgomery County, Virginia (37.27571°N, 80.418900°W; WGS84). This is locality 11 of Kreisa and Bambach (Reference Kreisa and Bambach1973). A detailed section of this site (with lithologies including sandstone, siltstone, claystone, and mudstone) was given by Brown (Reference Brown1983), who placed it in the upper part of the Price Formation. The fine-grained intervals are near the base of the section; a coal layer is near the top. Plants from the site listed by Jennings (Reference Jennings1975) and Scheckler (Reference Scheckler1978, cited in Brown, Reference Brown1983) consist of: Lepidodendropsis scobiniformes (Meek, Reference Meek1880); L. vandergrachtii Jongmans, Gothan, and Darrah, Reference Jongmans, Gothan and Darrah1937; Lepidophylloides sp., Protostigmaria eggertiana Jennings, Reference Jennings1975 (miscopied by Brown, Reference Brown1983, as Protostigmaria essetiema); and Rhodea sp. The exact horizons yielding the eurypterid specimens are not known. The eurypterids from Coal Bank Hollow were briefly discussed in Briggs and Rolfe (Reference Briggs and Rolfe1983), based on preliminary observations by Plotnick.

Locality 2: Pond Lick Hollow

An exposure along County Route 674 (Pond Lick Hollow Road), west of Pulaski, Pulaski County, Virginia (37.054°N, 80.800°W; WGS84). This is near to locality 6 of Kreisa and Bambach (Reference Kreisa and Bambach1973) and is probably section C of Brown (Reference Brown1983, p. 54). This is also a coarsening upward sequence, with claystone at base and sandstone at the top. The specimens come from a gray/mottled white fine-grained shale with abundant iron stains, with a diverse associated flora including Triphyllopteris, Rhodeopteridium (Rhodea), Neuropteris, Lagenospermum, and Gnetopsis (P. Gensel, personal communication, 1981). Neuropteris antiqua (Stur, Reference Stur1877) and Rhodeopteridium sp. occur on the slab (P. Gensel, personal communication, 2018) that includes the eurypterid (Gensel, Reference Gensel1988). Again, the exact horizon of the eurypterid specimen is not known.

The two localities are non-marine strata, associated directly with the Price Formation delta complex. They are either delta plain (Facies 7 of Kreisa and Bambach, Reference Kreisa and Bambach1973) or swamp (Facies 8 of Kreisa and Bambach, Reference Kreisa and Bambach1973). Gensel (personal communication, 1981) favored either a levee or channel area of a delta plain deposit for the Pond Lick Hollow Road specimen.

Materials and methods

Specimens from Coal Bank Hollow were collected by faculty and students at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, including Chauncey G. Tillman, Frank Whitten, and David Goodman, and deposited in the collections of the Department of Geological Sciences. In 2021 they were transferred to the Virginia Museum of Natural History and given specimen numbers. The specimen from Pond Lick Hollow was collected by Patricia Gensel.

Specimens were photographed with a Canon PowerShot Pro Series S5 IS digital camera. Figure 1.1 was drawn with a camera lucida attached to a Wild M5 binocular microscope.

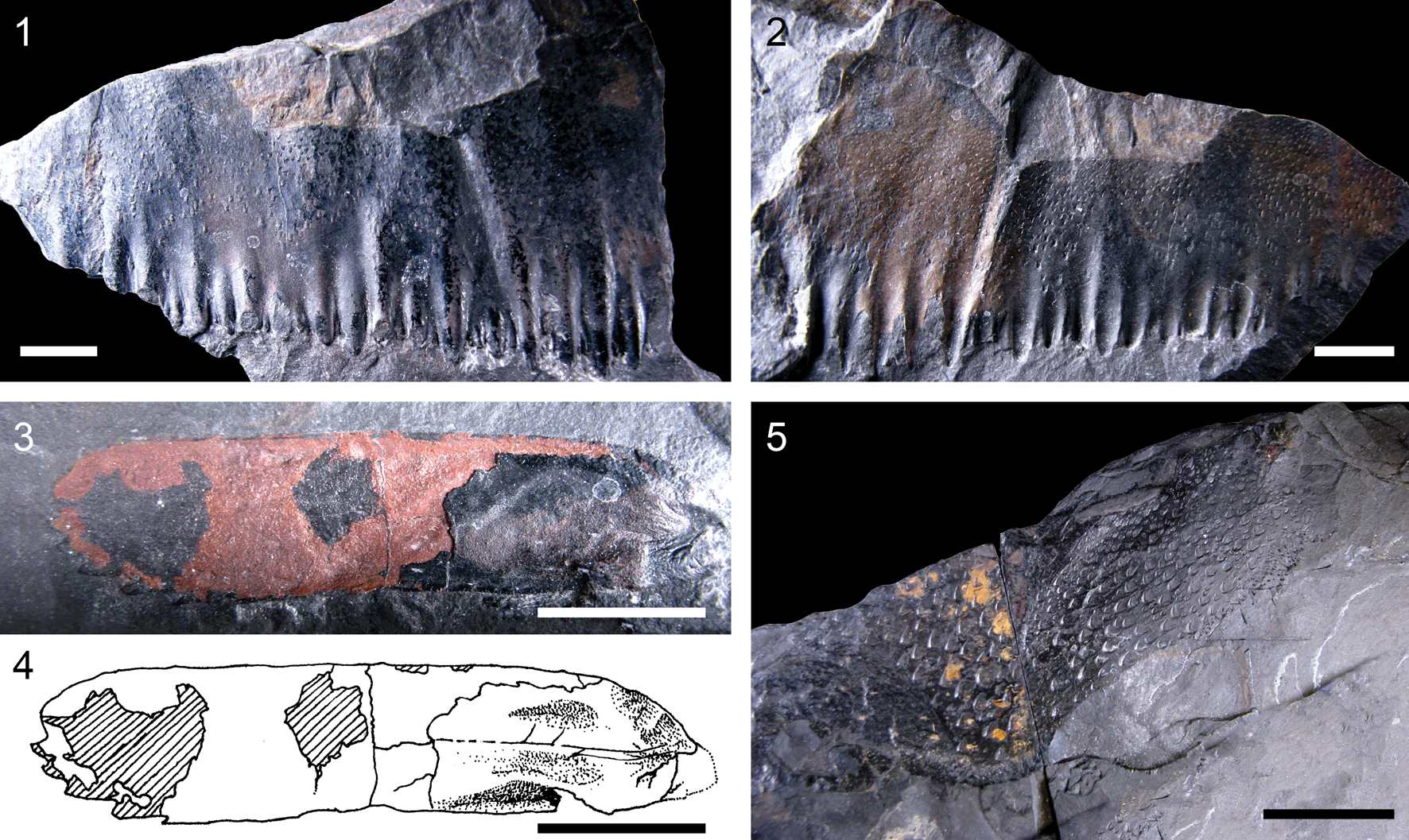

Figure 1. Cyrtoctenus bambachi n. sp. Price Formation, Lower Mississippian, Coal Bank Hollow, Virginia. (1, 2) VMNH 129166, opisthosomal tergite (paratype, part and counterpart). (3) Holotype: VMNH 129168, isolated free finger of prosomal appendage armature. (4) Camera lucida drawing of VMNH 129168. (5) VMNH 129169, cuticle and ornamentation (paratype). All scales 10 mm.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Type and figured specimens examined in this study are deposited in the following institutions: Virginia Museum of Natural History (VMNH), Martinsville, Virginia, USA, and the paleontology collections of the University of North Carolina (NCUPC), Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Systematic paleontology

Order Eurypterida Burmeister, Reference Burmeister1843

Suborder Stylonurina Diener, Reference Diener and Diener1924

Family Hibbertopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering, Reference Kjellesvig-Waering1959

Genus Cyrtoctenus Størmer and Waterston, Reference Størmer and Waterston1968

Type species

Cyrtoctenus peachi Størmer and Waterston, Reference Waterston1968.

Cyrtoctenus bambachi new species

Figure 1

Holotype

VMNH 129168. Mississippian (Tournaisian), Price Formation, Coal Bank Hollow, near Blacksburg, Virginia, USA. Paratypes: VMNH 129166 and VMNH 129169.

Diagnosis

Cyrtoctenus with cuticular ornamentation comprised of both acicular and lunate scales; prosomal appendage podomeres lacking distal crenulations; moveable fingers of prosomal appendage armature straight, expanding slightly distally, with rounded termination.

Occurrence

Price Formation, Tournaisian (Kinderhookian–Osagean), at Coal Bank Hollow, Blacksburg, Virginia (37.27571°N, 80.418900°W), preserved in black shale.

Description

Each type specimen is described individually below.

Holotype VMNH 129168

Specimen comprises a moveable finger or blade with a length of 60 mm and a width of 10 mm proximally, expanding to 13 mm wide distally. The anterior (or dorsal) margin is straight, demarcated by a thickened ridge of imbricate scales. The posterior (or ventral margin) is slightly curved and is also ornamented with a ridge of imbricate scales. The distal termination of the finger is rounded, with four scales from the posterior margin projecting out to form blunt spines.

Paratype VMNH 129166

Fragment of opisthosomal tergite in part and counterpart, preserved width 92 mm, preserved length 53 mm. No natural edge of the tergite is preserved except for the posterior margin, which is crenulated. Tergite strongly ornamented. Ornamentation grades from dense, small acicular scales anteriorly to larger, increasingly spread-out lunate scales posteriorly. The crenulation along the posterior margin is formed from a dense accumulation massively enlarged lunate scales that show significant relief, forming longitudinal ridges and furrows.

Paratype VMNH 129169

Fragment of cuticle, most likely part of a prosomal appendage. The specimen has a length of 91 mm and is 21 mm wide proximally, expanding to 50 mm wide distally, with a recurved distal margin. The podomere is densely ornamented with acicular and semilunate scales that increase in size distally. An indentation running down the center of the podomere for 66 mm may represent a ventral groove.

Etymology

Named for Richard K. Bambach, in honor of his many contributions to paleontology and the education of generations of paleontologists.

Materials

Holotype VMNH 129168 and paratypes VMNH 129166 and VMNH 129169.

Remarks

Braddy et al. (Reference Braddy, Lerner and Lucas2022) synonymized the hibbertopterid genera Hibbertopterus, Dunsopterus, and Vernonopterus, but considered Cyrtoctenus to be distinct due to the presence of combs on the prosomal appendages. The Coal Bank Hollow material exhibits a tergite ornamentation more typical of Hibbertopterus (illustrated as Campylocephalus by Waterston, Reference Waterston1957) with dense acicular scales, and the enlarged acicular scales forming crenulations along the tergite posterior in VMNH 129166 specimens are also observed in specimens of Hibbertopterus formerly assigned to Dunsopterus (Waterston, Reference Waterston1968). The morphology of the podomere preserved at Coal Bank Hollow, VMNH 129169, closely matches podomeres of Hibbertopterus stevensoni (Etheridge, Reference Etheridge1877) in ornamentation and overall morphology (Waterston, Reference Waterston1968). However, the moveable finger (VMNH 129168) is a clear indicator that the new species possessed combs and therefore is assignable to Cyrtoctenus (Størmer and Waterston, Reference Waterston1968; Waterston et al., Reference Waterston, Oelofsen and Oosthuizen1985). The combination of traits in the new species further suggests that the genera Hibbertopterus and Cyrtoctenus may be synonyms (Jeram and Selden, Reference Jeram and Selden1994; Lamsdell et al., Reference Lamsdell, Braddy and Tetlie2010; Lamsdell, Reference Lamsdell2013), although the current material is too sparse to warrant a full reassessment of the genera.

Despite being known from only a handful of fragmentary specimens, Cyrtoctenus bambachi n. sp. can be differentiated from other currently known Cyrtoctenus species based on the morphology of the moveable finger. The moveable fingers of Cyrtoctenus peachi and Cyrtoctenus dewalqui (Fraipont, Reference Fraipont1889) are curved, narrow distally, and have pointed terminations (Størmer and Waterston, Reference Waterston1968), quite unlike those of Cyrtoctenus bambachi n. sp. Cyrtoctenus wittebergensis possesses moveable fingers that are straight, as in Cyrtoctenus bambachi n. sp., but narrow distally and terminate in a point. The moveable finger of Cyrtoctenus bambachi n. sp. is therefore unique among known Cyrtoctenus species in broadening distally and having a rounded termination. The lack of crenulations on the appendage podomere distal margins is also unique among Cyrtoctenus species.

Stylonurina incertae sedis

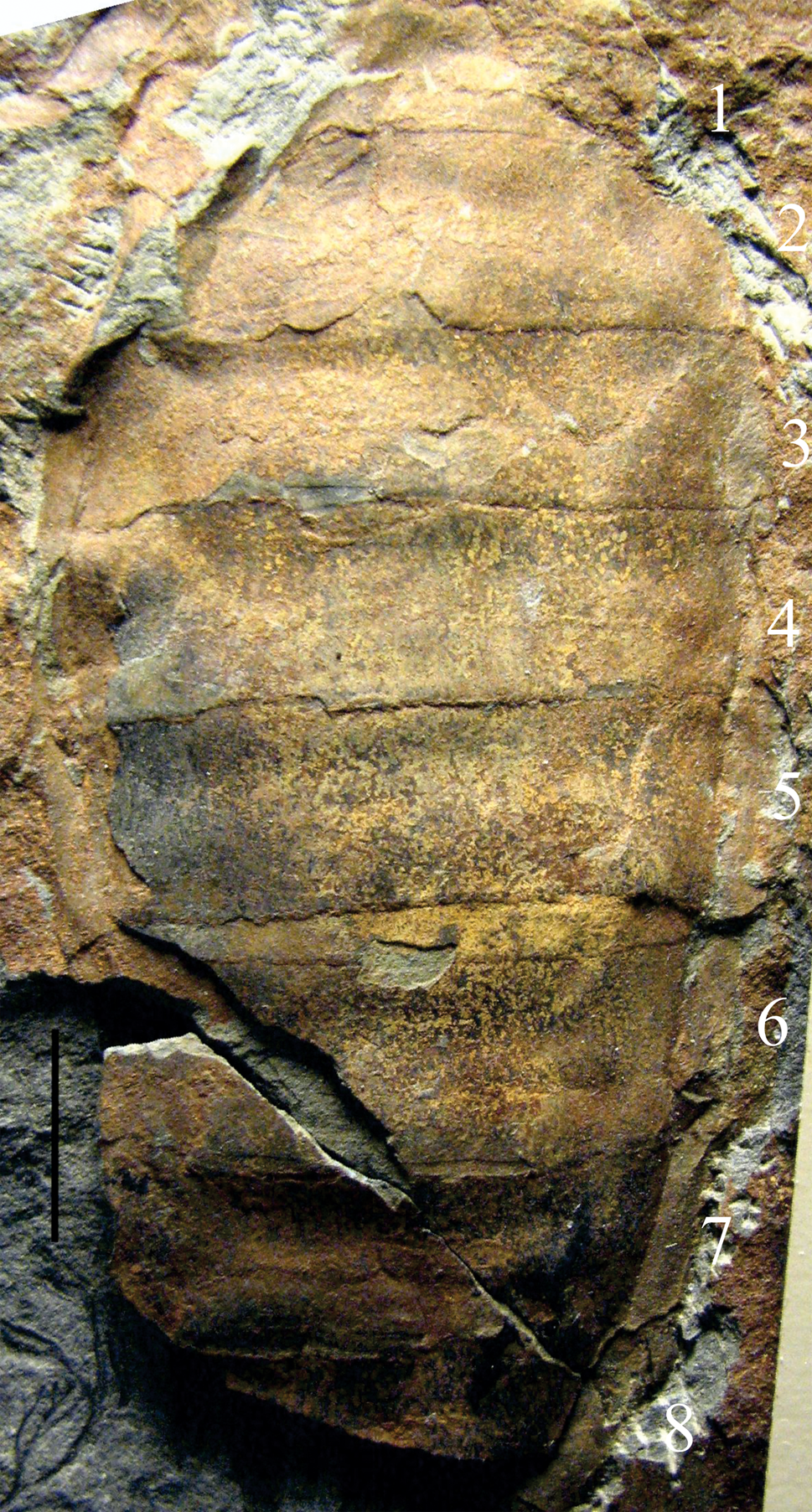

Figure 2

Occurrence

Price Formation (Mississippian age) at Pond Lick Hollow Road (Co. Rt. 674), west of Pulaski, Virginia in gray shale with abundant plant fragments.

Figure 2. Stylonurina incertae sedis. Price Formation, Lower Mississippian, Pond Lick Hollow Road near Pulaski, Virginia. NCUPC 135A. Segments numbered 1–8. Scale 10 mm.

Description

Seven, possibly eight, opisthosomal segments preserved with some relief. Anterior and posterior broken and incomplete. A large crack runs through the posterior of the specimen; the portion posterior to this can be removed. No discernable ornamentation, trilobation, or division into preabdomen and postabdomen. Segment 1 is short. Indication of a marginal rim on some segments (left side segments 3–5; Fig. 2). Total length is 67 mm, maximum width is 29 mm.

Material

NCUPC 135A.

Remarks

The specimen lacks sufficient characters to confidently assign it to a taxon within the eurypterids. The lack of ornamentation on the segments, as well as no clear indication of a division into pre- and postabdomen, argues against inclusion within the Adelophthalmidae, the surviving clade of the Eurypterina (Lamsdell and Selden, Reference Lamsdell and Selden2017). The overall shape, smooth texture, and marginal rim resemble members of the Stylonurina, such as the Upper Devonian Stylonurella(?) beecheri Hall and Clarke, Reference Hall and Clarke1888 (Plotnick, Reference Plotnick2022, fig. 8). Pending additional specimens, we place it as incertae sedis within the Stylonurina.

Discussion

Although eurypterids are relatively common in both Late Devonian and Pennsylvanian terrestrial settings, they are by comparison extraordinarily rare in the Mississippian (Tetlie, Reference Tetlie2007; Lamsdell and Selden, Reference Lamsdell and Selden2017). No members of the clade have been documented previously from North America. These specimens thus fill a key break in our understanding of the later history of this group.

Ward et al. (Reference Ward, Labandeira, Laurin and Berner2006) suggested that terrestrial arthropods showed a chronological gap during the Visean equivalent to Romer's gap for vertebrates, which they attributed to low atmospheric oxygen levels. On the face of it, the record of Carboniferous eurypterids supports the existence of an arthropod gap. The forms reported here support the contention by Smithson et al. (Reference Smithson, Wood, Marshall and Clack2012) that the gap is an artifact of collection failure, with additional eurypterid material from this interval awaiting future discoveries.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply thankful to R. Bambach for introducing us to the specimens from Coal Bank Hollow and allowing us to borrow them for an interminable amount of time. P. Gensel is similarly thanked for her loan of the specimen from Pond Lick Hollow and for her comments on its provenance and environment. J. Dunlop and an anonymous reviewer made useful comments which notably improved the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare none.