I

Common rights were an integral part of the feudal economy of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, as well as the Polish lands incorporated by Russia, Prussia, and Austria at the end of the eighteenth century. Common rights had an undeniable impact on social relations and the economic standard of living, in many cases leading to harsh conflict, which has only been described from a general point of view in Polish historiography. The key social groups perceived common rights as a symbol of vital interests. The collapse of the First Polish Republic at the end of the eighteenth century and its aftermath had a clear impact on quality of life among the peasants, townspeople, nobility, and clergy. The next few decades brought fundamental economic changes to the Polish lands seized by Austria, known as the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria between 1772–1918.

In this context, this article considers common rights to cattle grazing in Austrian Galicia in relation to a specific temporal and territorial turning point, as well as historical events. The problem of disputes over common rights was constantly present in the socio-economic space. Given the diversity, scale, and form of the conflicts, they have been characterised by dividing them into the key periods of the existence of common rights for cattle grazing, determined by historical events and Austrian legislation on the abolition and regulation of common rights. A landmark date was the start of agrarian reforms in Galicia and the entire Habsburg monarchy in 1848, which ended the feudal era. For this reason, there is a clear difference between how common rights operated and the form of conflicts in 1772–1848, and in the second half of the nineteenth century.

This article aims to clarify the main research problems. The key questions concern the subject and causes of the most common disputes during that period. Why, in the context of common rights for cattle grazing, were there such frequent social conflicts? What role did corporal punishment play in conflicts? How did limiting common rights affect peasant families’ quality of life during the feudal period and after the agrarian reforms? Why was the abolition of common rights so drawn out in time? What was the Austrian administration’s role? How did the reform abolishing common rights affect the modernisation of the entire province and the extent to which peasant farms were pauperised? Did the compensation for the abolition of common rights improve peasants’ and townspeople’s standard of living? How did the separation of some of the pastures and meadows from court areas as compensation for abolished rights affect the functioning of larger landed estates? To what extent were conflicts over common rights for cattle grazing hampered by modernisation in Galicia?

Research on common rights for cattle that existed in the Polish lands in the nineteenth century is important, not only for generating new knowledge and comparing it with research in other European countries. Above all, it enables historians to consider the impact of conflicts over common rights when explaining historical events and processes, which can alter how they are perceived. The results also have a practical significance, as some present-day land communities and urban property (such as economic zones in cities) were established in the process of abolishing the common rights for cattle in Galicia.

II

This research is based on an analysis of sources housed at the Central State Historical Archives of Ukraine in Lviv. The C. K. Namiestnictwo Galicyjskie (фонд 146) archival collection contains over 12,000 items on the functioning, conflicts, and abolition of common rights in the whole of Galicia during the nineteenth century.Footnote 1 Given the remarkable richness of the manuscripts, materials were selected critically, resulting in a group of documents characterising each type of conflict over common rights. This is loose documentation, bringing together a wide variety of manuscript types. Most of these materials were used for the first time and had not been put in order before. In the vast documentation, all kinds of complaints, grievances, denunciations, and allegations play a leading role. Depending on the period analysed, they were sent to landowners, who were the first judicial instance under patrimonial jurisdiction, the local and provincial Austrian administration, the courts, the central authorities, and the emperor himself. When identifying and following disputes, documents from the administration, committees, and courts settling all kinds of conflicts proved to be exceptionally important. These were mainly protocols, reports, correspondence, sketches, cadastral maps, and people being questioned. Research at the Central Archive in Lviv contributed to the discovery of a significant collection of sources that had not been edited or made available before. The materials in the Tabula National (фонд 166) unit is a collection of several thousand final rulings settling all kinds of disputes over common rights in nineteenth-century Galicia.Footnote 2

The richness and variety of the archival materials required the right methodology. A heuristic approach was used to locate, systematise, and choose sources. When studying and analysing the documents, the facts were established directly; hermeneutics and internal criticism were used to verify the information’s credibility, especially in complaints, which were often tinted by the alleged offences and conflicts described. With the correct external and internal interpretation of the sources, and by comparing conflicts in different regions of Galicia, the author was able to draw credible conclusions. The article also uses cartographic methods based on geographic information systems (GIS).Footnote 3 These were used to map the places where conflicts over common rights and the ownership of meadows and pastures broke out. The digitisation, vectorisation, and georeferencing of cadastral maps from the mid-nineteenth century, combined with analysis of the manuscripts, brought measurable results, including the cartographic representation of the conflicts and changes in the ownership of meadows, pastures, and forests allocated as compensation for the abolition of grazing rights.

III

Common rights were widely known and used in the Commonwealth’s economic system. Polish historiography has repeatedly shown that the definition of common rights in Polish law was synonymous with the Roman concept of servitutes praediorum. However, different terminology was used.Footnote 4 During the Middle Ages and the modern period, they were usually described using the Latin terms libertates and onus, the general Polish term wolności and individual names for a specific right that existed in the Polish lands, such as gajne, żołądź, or wrąb.Footnote 5

In the nineteenth century, they were officially referred to as Servituten in legal acts and German-language historiography in the Polish lands incorporated in Austria, but the Polish names serwituty and służebności dominated.Footnote 6 Common rights to land were also present in other European countries. They usually applied to common land where at least a few farms grazed cattle together after the harvest and on permanent grassland, collected hay from the meadows, and wood from the forest. One example is the common rights that existed in England, such as the right to graze animals, to fish (common of piscary), to dig peat (common of turbary) and to gather wood in the forest (estovers).Footnote 7

The establishment of common rights in the Commonwealth can be understood as the need to grant the largest social groups access to natural resources belonging to the monarchy, nobility, and clergy. This created a relationship between the owners and the users of two properties. The owner merely obtained the right to use the natural resources of another property, based on the principle by which common rights operated (servitutes praediorum).Footnote 8 This understanding of wolność allowed the peasants, townspeople, and clergy to use raw materials on manorial land (private and royal) and common land. Meadows, pastures, stubble fields, fallow lands, forests, rivers, and lakes were a source for satisfying basic needs. Firewood was used to heat homes and cook meals, while grazing cattle allowed people to maintain the livestock needed to support their families, work in the fields, and perform the duties of serfdom. Of the numerous common rights that existed in the Polish lands, the most important were: the right to collect firewood and wood for building (wrąb); the right to graze cattle in meadows, pastures, fallow land, and in the forest; the right to use water resources (watering cattle, soaking hemp); the right of passage, moving cattle; as well as the right to dig raw materials from the ground (usually clay and sand) and to collect fruit and flowers. The party entitled to exercise a given right was usually the village, the rural or urban commune, a specific group or individual, or the clergy.Footnote 9

In the Commonwealth, common rights to land could be established with the property owner’s knowledge and approval, or regardless of their will. The latter usually included rights resulting from legislation. In both Polish and Lithuanian law, the grazing of animals was in some cases subject to penalties for damage caused. This is mentioned in Articles 130 and 131 of the Statutes of Casimir the Great from the fourteenth century, among others. People were fined for grazing horned cattle without supervision during a certain season of the year; for the unauthorised grazing of pigs in the forest, the penalties were harsher. For the first instance, the owner of the forest could slaughter one pig from the entire herd. If they found the same person breaking the law again, they could kill two pigs. On the third instance, they could confiscate the entire herd and take it to the closest royal farm. Half of it went to the king and the rest to the owner of the forest.Footnote 10 In the fifteenth century, merchants also had the right to grazing. They could exercise it without informing the owner of the property, but only on fallow land, stubble, and wasteland, and only up to a single day.Footnote 11

Common rights could also be established with the permission and knowledge of the owner of the property. These were the most frequently applied rights, resulting directly from the act creating them (sections of village and town localisation acts, parish foundation acts, grants and privileges). The documents establishing common rights could foresee so-called reciprocity; the obligation of a person with, say, the right to graze geese on court pastures to pay fixed fees in kind, money, or labour per grazing animal. As a rule, though, the reciprocity in the strict sense was the peasants’ serf work on the court grounds and additional labour (for example, szarwarki). Moreover, grazing cattle on court property and common land was usually subject to certain rules resulting from the act creating the specific law. The conditions of its execution could differ significantly for people living on property that belonged to different owners. The regulations primarily concerned the class of property (pasture, meadow, stubble, fallow, or forest) and the designated common right areas on them, where grazing was allowed, as well as several other factors, such as the permitted grazing time over the course of the year and the day itself, the number, species, weight, and age of the cattle, the forms and value of reciprocity, joint or individual grazing of cattle owned by peasants, townspeople, the court and the parish, the supervision of grazing cattle (hiring a shepherd or making peasants do it), and penalties for damage.Footnote 12

The common right to cattle grazing was an exceptionally popular and commonly exercised right with a special significance attached to it. The right to grazing, especially at the time of the feudal economy, could bring the parties mutual benefits – both the party exercising the right and the owner of the property. For peasants, owning cattle enabled them to support a family (mainly by producing dairy produce). Maintaining the good condition of bulls and horses was in the court’s interest because serfdom services involving horse-drawn vehicles brought more benefits than those done on foot.Footnote 13 Moreover, as part of mutual benefits, the court could derive income from grazing rights.Footnote 14 A similar practice could be observed in the case of grazing on common land. The commune (gmina), as the owner of the property, collected a charge for the grazing cattle from people living in neighbouring localities.Footnote 15 From an economic perspective, certain rights lost significance and ceased to be attractive, or were sometimes treated as harmful, especially after serfdom was abolished in Galicia in 1848. In terms of their impact on natural goods, the historiography has been critical of certain rights, in particular those concerning cattle grazing in the forest. It primarily pointed to the damage to young trees (młodniki) by cattle, which trampled them and bit off shoots and leaves. This resulted in trees fading away or growing stunted, which meant that they could only be used as firewood. Criticism focused on entitled peasants who repeatedly grazed cattle in the forest without restrictions and supervision.Footnote 16 The firmly negative impact of grazing cattle in the forest was also raised in academic circles. The archival observations of Bronisław Borkowski,Footnote 17 a student at the Institute of Rural Economy and Forestry in Marymont in 1848 (now the Warsaw University of Life Sciences), concentrate on a few key points that are especially important when it comes to protecting the forest. He considered the most harmful to be: allowing goats and horses to graze in the forest (where they could bite off the young shoots of trees), the joint grazing of cattle and sheep, allowing animals to be near trees with the best tasting leaves (such as oak, aspen, hazel, and elm), and ground erosion by sheep in mountain areas.Footnote 18 The excessive use of forest resources could already be seen clearly in the eighteenth century. Bringing in too many sheep, disordered grazing, and degradation of the forest were particularly evident in the Tatra Mountains. The first attempts to prevent the ill consequences took place at the start of the nineteenth century, yet changes in the division of ownership of mountain pasturesFootnote 19 intensified the phenomenon. Despite the abolition and regulation of common rights in the second half of the nineteenth century in Galicia, cattle were still being grazed in pastures and forests in the Tatras a century later. It is now limited to so-called cultural grazing on designated pastures, which does not have a negative impact on nature.Footnote 20

The distinctive feature of common rights on the Polish lands was their direct relationship with the feudal system. Most of the rights resulted from the relationship of authority between the landowners and the subordinate population.Footnote 21 The collapse of the Commonwealth at the end of the eighteenth century did not change this situation. Most of the previous rights were maintained on the lands incorporated into the Austrian Empire, but some were limited or there were attempts to regulate them. One of these acts, relating to cattle grazing in the forest, among other things, was the forest law of 1782, and the later patent of 1807.Footnote 22 The reforms of Empress Maria Theresa and her son, Emperor Joseph II in Galicia were crucial for exercising the right to cattle grazing on court and common land, as well as subsequent disputes over property ownership and use. Of the many changes that had a positive impact on the peasants’ position,Footnote 23 the demarcation of the land used by the peasants (rustical) and those remaining at the manorial farms (dominical) was especially important. The assignment of property in the later land cadastres of 1785–7 and 1820 to one group or the other was used to recognise the state of ownership (of one or several entities) and those authorised to graze cattle. Conflicts over the right of ownership and cattle grazing in the following decades showed that extracts from the cadastres were among the most important types of written evidence during trials.Footnote 24 Furthermore, Joseph II’s reforms significantly limited the ability to remove peasants from the land, including the incorporation of rustical pastures and meadows in farms as common lands. This significantly reduced abuse by the nobility, although the scale of disputes over the appropriation of rustical common lands throughout the nineteenth century indicated that it was not enough.Footnote 25

Analysis of the archival sources from 1772–1918 shows that, depending on the period studied, conflicts over common rights to cattle grazing in Austrian Galicia differed significantly in terms of scale and form. Based on the selection and interpretation of documents, three main periods of fundamental significance for the functioning and process of abolishing common rights were identified:

-

1. 1772–1848 – the feudal economy;

-

2. 1848–57 – a transition period between the abolition of serfdom and the issuing of laws and ordinances abolishing common rights;

-

3. 1857–1918 – the real process of abolishing common rights, that is, redemption and regulating rights.

The new reality in which the inhabitants of the Polish lands found themselves under Habsburg rule in 1772 brought many changes, which affected all social groups. The new legal regulations relating to common rights were primarily directed at normalising forest management. Freedom to interpret the legal regulations meant that landowners drastically restricted or denied subjects access to their forests. For common rights to cattle grazing on non-forested land, the situation was different. The new Austrian legislator chose not to regulate these rights. The 1787 ban on replacing rustical land with dominical land was not categorically observed. Pastures and meadows used jointly by villages and the court were listed as court properties in the land cadastre during the reign of Joseph II, which later provoked sharp disputes over ownership. Anticipating the facts, landowners transformed the property’s class into arable fields after adding it to the cadastres, which in practice meant that villages lost grazing and property rights. The right to grazing on stubble and court fallow looked more beneficial from the perspective of the peasants, but in this case reciprocity was obligatory: court cattle grazed on peasant wasteland. However, the matter of fees for grazing animals was regulated. A patent from 1786 prohibited the introduction of new benefits in relation to exercised rights on properties where there had been free grazing rights up to that time.Footnote 26

The problems raised in the historiography provide a clear context, introducing the fundamental problem of disputes over rights to cattle grazing, immortalised in archival sources. The main causes of conflict in feudal Galicia (1772–1848) were part of the complex relationship between the subordinated peasantry, townspeople, and the court authority. There is no doubt that the source of most antagonisms was the stronger position of the landowners (nobility), who treated rustical real estate as their unrestricted property. Families with these sorts of aspirations included the Jabłonowskis, who owned the villages of Jaszczew and Bajda. In 1811, a conflict broke out over a pasture with an area of ninety morgens,Footnote 27 where the cattle of all the peasants in Jaszczew and the manor grazed together. Without informing anyone about his intentions, the owner of the village sold half the property to his neighbour, while the rest was incorporated into the manorial estate and turned into arable fields and meadows. He informed the protesting peasants that they no longer had grazing rights and that he would not change his mind. That same year, Jaszczew’s inhabitants submitted an extensive complaint to the local circular office, but for unclear reasons the authorities did not take an interest in the problem until two years later, after several more complaints.Footnote 28 In 1824, based on the commission’s investigation, the circular commissioner told the village that the law had been broken and that the pasture should be returned to the village. The village owner did not comply with the ruling, so the peasants presented the problem to the Court Office in Vienna. In 1826, the Chancellery issued a decree recognising the damage to the peasants and ordering an investigation into the return of the pastures, and compensation for the losses resulting from the inability to graze cattle and the obligation to pay taxes on the entire property. This was not the end of the conflict, though. Despite the adoption of the court decree and its confirmation by the local Galician authorities, no action was taken to comply with it. It took further complaints for a decision ordering that the pastures, along with 2,550 guilders in estimated damage to the farmers, be returned to be issued. This decision was made in 1829, but the village owner still did not intend to comply. Four years later, unable to execute the verdict, the peasants wrote to Franz Krieg von Hochfelden, Governor of Galicia, asking him to intervene. In the end, the dispute was not unequivocally resolved. Despite many complaints and pleas, the peasants did not receive a decision under criminal sanction and the landowner did not return the seized pastures or provide the village with compensation.Footnote 29 Jabłonowski’s authoritarian approach was no exception; it reflected common practice in the whole province. The conflict between the court and the village also exposes other problems present in social relations in Galicia. The administration’s tardiness, both in conducting the investigation and in issuing decisions, is clearly visible. This resulted in negative consequences linked to the fiscal burden on farms and the ability to support cattle. The contested pasture was listed as rustical in the cadastre at the end of the eighteenth century, so the peasants were forced to pay taxes, even though they could not use it from 1811. In addition, using the shared pasture enabled more cattle to be kept. The sudden loss of this ability led to a decrease in the number of their animals, which the peasants paid particular attention to in their complaints.

Disputes over the appropriation of rustical pastures where peasants grazed cattle often took a harsher form. In those cases, the court administration used corporal punishment and physical violence towards peasants who disagreed with the landowners’ actions and complained to the local administration. This happened in the village of Hołuczków in 1822, where the owner, Ignacy Popiel, claimed five pastures – on which court and village cattle grazed together – as his own. The peasants did not object, indicating that it was the right to graze cattle that was key for the whole village. They also saw financial benefits and demanded that Popiel pay taxes for owning the pastures. The court’s further actions led to a serious conflict: Popiel refused to pay taxes and banned the grazing of village cattle. After learning about the complaints made to the district administration, he ordered the court service to punish the active peasants by beating them with a stick and kicking them. However, the village did not stop striving for the right to graze cattle on the appropriated pastures, and subsequent complaints were accompanied by detailed lists of the people who had been beaten, including their name, occupation, public function, and punishment. In 1826, the local administration launched an investigation, as a result of which the village was meant to receive from the court a pasture elsewhere of the same area, as compensation for its loss. However, the ruling did not involve a sanction, so Popiel did not feel obliged to comply.Footnote 30

It was common for the court administration in Galicia to subject the peasants to corporal punishment.Footnote 31 This was linked to the landowners (nobility) exercising judicial power of the first instance. It was treated as completely normal, both in administering justice for breaking the law and as a way of disciplining the peasants in their work as serfs. This meant that the peasants were often abused and mistreated by the court service. Corporal punishment had a particularly negative psychological impact on the peasants, affecting their personal dignity and instilling a belief that beating with scourges, whips, and sticks was right and should be humbly endured. The legislation of the time in Galicia, especially the provisional patent of 1775, had a positive impact on the peasants’ moral position. It limited the right to exercise corporal punishment and allowed complaints concerning court abuse to be submitted directly to district officials. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the punishment for the unjustified beating of subjects was usually a fine – one guilder per blow with a stick.Footnote 32 This is confirmed by the situation in the village of Hołuczków. One of the complaints notes that ‘[h]aving shut himself up with the caretaker, Ignacy Popiel beat to the blood with 15 or 18 strokes saying: I will give 100 blows and pay 100 Rhenish [guilders].’Footnote 33

Disputes over the right to use common pastures were often part of deeper conflicts between subjects and the court. Filing a complaint on one issue, the peasants would use it as an opportunity to inform officials about all the problems and abuse by the court service. Analysing and comparing many sources shows that the authors of the complaints and grievances usually deliberately coloured and exaggerated selected problems to impress the officials and get them to intervene. This also resulted from the slowness of the administration, which was in no hurry to settle minor disputes. A classic example of presenting collective problems to the authorities were the complaints by six villages in the Baranów dominium (now Baranów Sandomierski) owned by the Krasicki family. In the 1820s and 1830s, the villages asked officials to intervene after the court appropriated village pastures, most of which was turned into a forest, with a new farm built on the rest. In the same documents, the peasants complain about strict treatment and the court judge’s almost unlimited power, the imposition of extra work in the fields and forest,Footnote 34 the introduction of new levies in kind, and the increase in the scope of mandatory tithes. When no reply was received, the complaint was sent to subsequent administrative instances, from the court administration, through the circular office, the Galician Governorate, the governor and the court in Vienna, to the emperor himself.Footnote 35 In this context, disputes over grazing cattle on jointly used pastures could be individual conflicts or could result indirectly from other problems and difficult relations between the peasants and the court. There is no doubt, however, that the appropriation of village or municipal property was always a huge loss for the subjects and deepened mutual dislike.

Most settlements in Galicia used their right to graze cattle on property owned by the court. This meant that the most common source of conflict were landowners’ actions linked to the introduction of various restrictions or mutual obligations. All kinds of disputes, even the most minor, were a good reason to try to receive official confirmation of one’s rights in writing. Villages and towns with this decision were aware that it would be easier for them to defend their interests if the court tried to restrict or deny their rights. Around 1800, the peasants in the village of Myscowa found themselves in this position. In 1804, the local district administration in Jasło settled the conflict between the village and the court over the peasants’ right to graze cattle on all court property (forests, pastures, meadows, and wasteland). The verdict confirmed all of the villagers’ claims, but the owner of the village appealed to the provincial authorities in Lwów. The decision in 1805 again confirmed the peasants’ rights to cattle grazing, but allowed the owner to introduce charges for each grazing cow. However, the court did not inform the Governorate; nor did it make the exercise of rights more difficult for the next dozen years or so. In 1821, the next conflict broke out. Citing the verdict from 1805, the landowner demanded that the peasants regulate the overdue charge for grazing cattle since 1804. The right to graze animals in court forests was also a point of contention. Amid the constant felling and change of land class into arable fields, the village complained about the court’s actions aimed at eliminating the right to grazing in that part of the forest, combined with the common right to water cattle.Footnote 36 The conflict was not finally settled until after the agrarian reforms, but its source reflected a common problem in feudal Galicia. It was linked to the practice of demanding unjustified benefits for the right to graze on court lands, or the misleading of illiterate peasants. In 1823, a vivid example occurred in the above-mentioned village of Hołuczków. Until 1820, peasants carried out additional serfdom on foot in exchange for the right to graze cattle on court property. The rule was that, for grazing one adult cow, ox, or horse from spring until autumn, the peasant or his journeyman had to perform one day per year of serf’s work for the court. The conflict was caused by the village owner’s decree introducing the same fee for grazing young animals.Footnote 37 The village did not agree to an additional burden, so Hołuczków’s owner opted for a forced solution, checking each peasant’s cowshed to see how many animals he had.Footnote 38

Feuds and disputes often broke out during grazing itself between animal owners. The joint grazing of cattle belonging to the village, court, and clergy led to many conflicts that resulted from inadequate supervision and handling of the animals, as well as frequent mistakes and misunderstandings between neighbours. This led to emotionally fraught situations such as theft, misappropriation, enforced acquisition for unpaid debt, or losses in inventory caused by allowing aggressive animals to graze together. The court was both the peacemaker and the first judicial instance. The loss suffered by one of the peasants in the village of Podhorce (in what is now Ukraine) in 1784 can serve as a point of reference. Inept supervision of cattle grazing together led to a priest’s bull attacking a peasant’s ox, which died from its injuries. This is best illustrated by sources stating that ‘the priest let his bull [buhaj] loose among the village cattle; playing with my ox, it gored it with its horns; it died three days later’.Footnote 39 The conflict broke out when the priest refused to provide compensation for the dead animal, so the peasant turned to the court for protection and to settle the dispute. In his complaint to the landowner, he mentioned the losses he and the court party had suffered, because he had lost the livestock that enabled him to perform serf’s work involving a vehicle drawn by an animal.Footnote 40

In the 1840s, talk of reforming the archaic system of farms and serfdom became increasingly common. Some of the nobility understood the need for change, too, but the proposed reforms discussed in the Galician Sejm of the Estates were repeatedly criticised by conservative factions. Despite the Sejm’s very limited and consultative role, a few drafts for reforming the feudal economy were prepared in the 1840s. People were aware that the archaic feudal economy was inefficient and had a negative influence on relations in rural areas. The first drafts by Kazimierz KrasickiFootnote 41 and Tadeusz Wasilewski on servile relations in the Sejm of the Estates also pointed to the need to abolish common rights and regulate common land.Footnote 42 In 1846, two members of the peasant affairs committee, Agenor Gołuchowski and Maurycy Kraiński, presented the Austrian authorities with a new draft reform envisaging the granting of land ownership to the peasantry, the abolition of serfdom, the separation of common land, and the abolition of common rights. However, it did not win support in ruling circles; nor did later reform proposals from landowners’ circles (including Aleksander Fredro). Amid growing social tensions, the Austrian authorities decided to introduce reforms in April 1848. Based on his powers of attorney, Franz Stadion, the Governor of Galicia – foreseeing the granting of land ownership to the peasantry – announced an imperial patent abolishing all serf labour and feudal tributes. The patent also referred to common rights; it ordered that they remain unchanged, but with the obligation to pay for them based on contracts with landowners.Footnote 43 Until the patent abolishing land and forest common rights in 1853 and regulations to the law of 1857, the most common disputes in Galicia related to the obligation to pay fees. Analysis of the sources shows that, during the transitional period between 1848–57, there were mass social antagonisms. These were caused by: denial of the common rights of the former subordinate peasants and townspeople; the imposition of exorbitant and unjustified fees in the form of labour in court fields and forests, natural goodsFootnote 44 and money; as well as the peasants’ reluctance to pay any rent. The abolition of serfdom deprived landowners of a free labour force, so they did not feel obliged to respect common rights. Peasants and townspeople repeatedly tried to forcefully assert their rights. This led to clashes with the court service, the eizure of cattle, theft, devastation, vengeful actions, and lawsuits.Footnote 45

Nineteenth-century Polish historiography repeatedly addressed the problem of common rights on the Polish lands, but usually in the context of their redemption and regulation, as well as land consolidation and the separation of common property.Footnote 46 Select publications point to the need to abolish common rights; the causes, form, and consequences of the conflicts are discussed more rarely. Analysis of the sources makes it possible to state that the most common source of disputes was the refusal to respect common rights when serfdom was abolished in 1848. This concerned both the right to collect wood and the right to graze cattle in court forests and pastures. A classic example of the conflict over the right of cattle grazing between the village and the landowner occurred in the village of Hucisko Jawornickie. Until the agrarian reforms, the peasants could graze cattle on all the court pastures, fallow land, and stubble with a total area of 180 morgens. Each farmer paid the contractual reciprocity per head of cattle. For one adult cow grazing from spring to autumn, he paid two chickens a year; for each heifer, he sent a hen to the court. With the abolition of serfdom, the village owner, Maria Sławik, forbade the peasants from using her property, accusing them of arrears in fees and unauthorised arbitrary cattle grazing without court supervision. From 1848 to 1953, the parties sent the Austrian administration numerous complaints, accusing each other of dishonesty, trying to make an easy profit and the appropriation of property. According to village representatives, the common right pastures belonged to the village, and charging peasants for this after the abolition of serfdom was unjustified. Sławik held the opposite view. Ultimately, the dispute was not settled until the village’s common rights were abolished in the 1860s.Footnote 47

The abolition of serfdom in 1848 deprived landowners of many streams of revenue; meanwhile, indemnification – compensation for the losses entailed – was only just being planned. The landowners’ new reality required the ability to run a farm based on workers who had to be paid. A way out of this tough financial situation was to incur debt against landed property and seek various sources of additional income. An easy way to achieve gains was to take advantage of owning extensive forests, pastures, and meadows. According to the patent abolishing serfdom, peasants who wanted to continue using common rights had to pay for them. This provided some scope for abuse and free interpretation. This was the attitude of Bonifacy Osuchowski and Jan Kanty Twardzikowski, the owners of the village of Kawęczyn.Footnote 48 Until 1848, court and village cattle grazed together on an extensive pasture. As soon as work ceased to be performed by serfs, the court deemed the pasture its exclusive property. One part was used as an arable field; on the rest, along with other court pastures, the peasants were offered the option of grazing cattle for an appropriate fee. This became an important source of income for Osuchowski and Twardzikowski, in the form of money, natural goods, and labour on the court fields. They classified their pastures in terms of quality. For grazing one head of adult horned cattle from spring until autumn on the best land, the owner had to work for four days a year and provide two chickens. For grazing on land of worse quality, money was collected. Some of the peasants in Kawęczyn did not accept the court’s conditions and tried to continue exercising their pre-1848 right to grazing by force. This led to regular quarrels and clashes with the court service, violent attempts to remove cattle from the pastures, and the seizure of animals on the pretext of overdue fees.Footnote 49

There were similar conflicts in many places in Galicia. In 1848–57, they were all linked to the introduction of fees by the owners of the common rights areas, which peasants and townspeople refused to accept, regardless of whether or not they were justified. If there was no agreement on the size and form of payments, decisions were made by local offices. Conflicts over the alleged appropriation of property were dealt with by special district committees or courts. As a rule, the proceedings were not settled formally, as these powers were taken over by common rights committees from 1857 to buy or regulate a given common right, which included resolving contentious issues. Both nineteenth-century and contemporary historiography indicate that the lack of swift action by the Austrian authorities to regulate the issue of common rights may have been deliberate. Krzysztof Ślusarek, who concurs with Walerian Kalinka, writes that ‘the abolition of serfdom and leaving common rights in force became a source of new conflicts between the court and the village community’.Footnote 50

The patent regulating the issue of easement rights was not published until five years after serfdom was abolished. For the former peasantry, townspeople, and landowners in Galicia, one of its key provisions was the abolition of land and forest common rights resulting from the prior relationship between sovereign and serfs. In the first place, they had to be abolished by redeeming them; if that was not possible, they had to be precisely regulated by the mutual agreement of the parties. However, the next few decades showed that the process was extremely drawn out. The patent’s provisions assumed that all common rights based on the subordinate relationship and the right for the village and court to own and use property jointly, as well as between municipalities themselves, should be abolished at the parties’ request, rather than ex officio.Footnote 51 The patent’s publication did not mean it was executed immediately. This was not possible until the regulation of 31st October 1857 containing the patent’s basic instructions. Over the new decade or so, nine regulations setting out how to proceed in disputes were issued.Footnote 52

Two main Imperial Commissions for the abolition and regulation of land burdens were established in 1855, in Kraków and in Lwów. Three years later, based on another regulation, seventeen local commissions for common rights were created to investigate specific cases. In 1867, the Kraków and Lwów commissions were merged, enabling the whole process of purchasing and regulation to accelerate. The first deadline for announcing the redemption or regulation of common rights was 17th March 1857. So-called provocations were submitted and the legal basis of the common right that needed to be bought was defined. In most cases, this was usucaption [zasiedzenie], the uninterrupted use of a property over several decades.Footnote 53

In the late 1850s, the local commissions started their work by examining cases that had been reported, and potential redemption or regulation. This was no easy task as most proceedings included conflicts. From the peasants’ perspective, the very idea of abolishing their rights was unappealing, so they fought for the status quo, the right to use court properties on the same terms as before 1848. Archival sources reveal antagonisms at every stage of the work. As a rule, the commission’s first step was to determine which common rights were subject to redemption and their legal basis. The interested party had to provide evidence of the granting of the rights and their recognition in official documents. The most important ones were based on written law. These were all sorts of documents from the Commonwealth: royal privileges,Footnote 54 records establishing parishes, village, and town localisation acts,Footnote 55 and all other nobility grants.Footnote 56 Also referred to repeatedly were official Austrian documents created after 1772. These included urbarial descriptionsFootnote 57 from 1789,Footnote 58 as well as administrative rulings and court judgements, which proved that peasants or townspeople had acquired common rights by usucaption, that is, the uninterrupted use of a property for thirty years. Conflicts at this stage of the committee’s work usually concerned the denial of the common rights’ legal credibility. This happened in Rymanów, among other towns. In 1859, the townspeople came forward to purchase the right to graze horned cattle and pigs on court pastures and forests. During the local commission’s session, they cited two legal bases: the privilege of Prince Jan Samuel Czartoryski from 1698 and, more importantly, usucaption, the uninterrupted exercise of common rights to grazing cattle since 1848. After reviewing the documentation, the commissioners rejected all the townspeople’s grievances and evidence, as the official documents from 1772–1848 did not contain any written confirmation of the exercised right to graze cattle. Instead, they concluded that the townspeople had grazed animals on court property, but only based on voluntary agreements with the court. As a result, the town was not entitled to any compensation. The townspeople repeatedly tried to block the commission’s sessions and appealed to the central authorities in Vienna. After a few years of unsuccessfully trying to change the local commission’s stance, they had to accept the final verdict of the Imperial Commission in Lwów, which rejected all their grievances.Footnote 59

If the commission recognised a village or town’s common right to graze cattle, it proceeded to characterise its form and estimate its value and dimension. All the detailed information was provided, like the seasons and days of the week when cattle could graze, the property intended for grazing, the type, age, and mass of the cattle, and forms of reciprocity in the form of fees.Footnote 60 Defining these triggered many emotions during the commission’s sessions in the presence of the court and villages. There were often conflicts of interest. To objectively estimate the value of rights over the course of a year, experts were appointed to prepare so-called technical estimates. Each party – the court and the village – had the right to appoint its expert. If the final estimates differed, the local commission appointed an arbitration expert [der Obmann], who calculated the value of the rights subject to redemption, settled disputes, and issued a decision on the method of redemption, which involved transferring the appropriate amount of money for abolished rights to the village or town, or separating the equivalent amount of pasture or forest from the court property.Footnote 61 A situation like this occurred in the village of Sindzina, near Wieliczka, during the redemption of the village’s common rights. The peasants’ protests disabled the commission’s work. The village – which was entitled to graze cattle on the court’s vast pasture – did not accept the technical experts’ estimates, deeming them too low. The municipality’s plenipotentiaries said that they did not agree to give them the equivalent amount of land from court property as compensation for the abolished right to grazing, as the proposed area was several times smaller than the pasture that they had used for the past few decades. Forced to limit the number of cattle, the peasants’ farms would inevitably have been impoverished. The plenipotentiaries consented to the rights being abolished, but on different conditions. They called for the technical estimates to be repeated, for their rights to be deemed more valuable, and for them to be granted the whole pasture that they had been using.Footnote 62 There is no doubt that the peasants’ high demands sought to obtain as much compensation as possible during the negotiations. It was anticipated that neither the court nor the local commission would agree to the full demands, but reducing the high claims made negotiations easier, thus the village could realistically expect to receive the compensation. In Sidzina, the peasants’ strategy worked. The conflict was settled after the rights were estimated again and partial concessions by both parties. The village agreed that, in exchange for receiving most of the pastures, it would be ready to grant the court the common right to dig for clay and sand there. Based on these conditions, an agreement and plan for abolishing the right to graze village cattle on court land in return for compensation were concluded. Disputes when estimating the value of rights, as in Sidzina, were among the most common problems faced during the redemption and regulation of common rights in Galicia. Moreover, other factors – the personal influence of owners, who often held important posts in Galicia, on commissioners, unfamiliarity with the regulations, mistakes in calculations, the commission’s shortcomings and bias, or the peasants’ reluctance to cooperate – meant that the results of the local commissions’ work could have a diametrically different ending. Analysis of the archival sources confirms the thesis that there were disputes at every stage of the commission’s work. Despite many feuds and conflicts, the local commissions’ decisions were presented to the Imperial Commission in Lwów, which usually issued a verdict in line with experts’ and local commissioners’ opinion. The Lwów bodies’ decisions could be appealed against to the Ministry of the Interior in Vienna, which happened repeatedly.Footnote 63

Conflicts during the abolition of common rights also concerned the form of compensation. Entitled villages or towns were repeatedly the initiating party and were the first to come forward to abolish common rights, eager to free themselves from the court’s decision and end longstanding antagonisms. Local committees’ negotiations in the presence of the court and village were made easier by both sides’ interest in resolving the matter. Despite a sincere desire, attempts to avoid disputes usually ended in failure. The form of compensation for the abolished grazing rights caused the most controversy. It was in the vital interest of villages and towns to receive a large and fertile equivalent of land. Conflict broke out when the court offered peasants the poorest quality area of its property. This happened in the village of Nowa Grobla in 1860. Until 1848, all the inhabitants had had the right to graze livestock – horses, mares, foals, cows, heifers, oxen, sheep, and pigs – for free, in all the court forests and pastures, at any time of day, from early spring to late autumn. After serfdom was abolished, the court signed an agreement with the village on the introduction of charges for the continued use of common rights. For the right to graze 282 head of cattle with a total weight of 1,120 Viennese pounds, the peasants had to perform 115 days of work in the court fields over the course of the year.Footnote 64

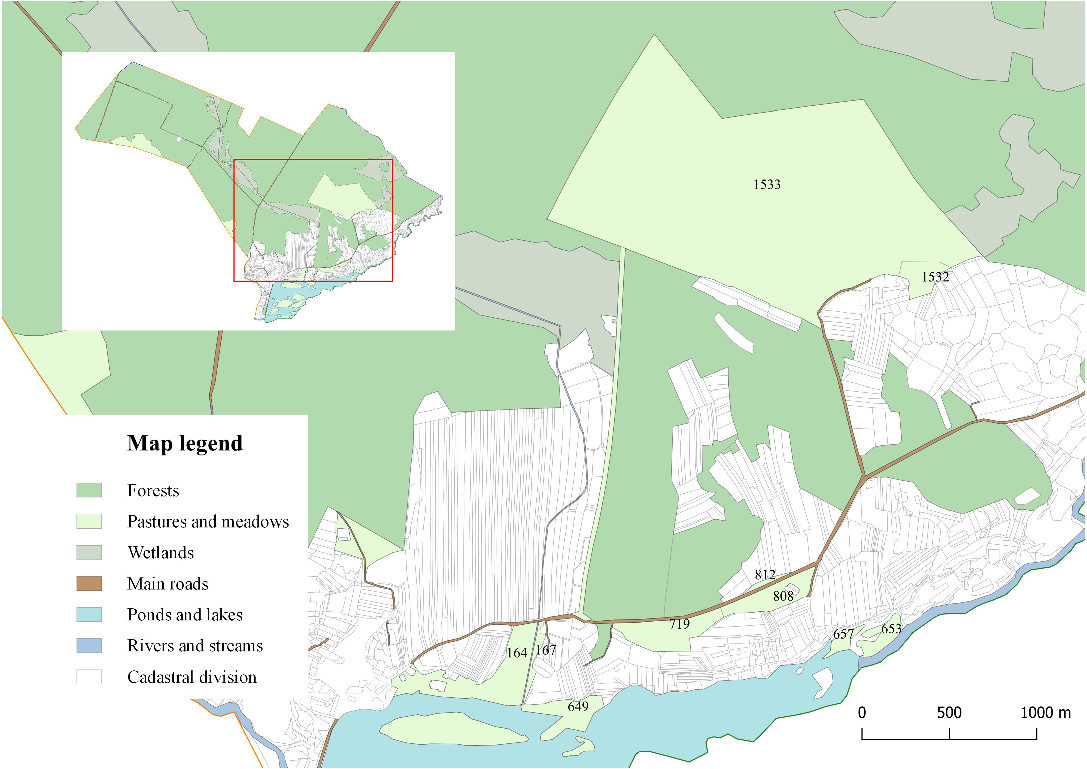

Figure 1 shows all the common right areas (court forests, meadows, and pastures) in Nowa Grobla where the peasants could graze cattle. After being digitised, the nineteenth-century cadastral map of the villageFootnote 65 was aligned and combined (seventeen sheets) with a graphics programme. Then, using QGIS 3.4.4 software, it was calibrated (georeferencing) based on EPSG reference system 3857 (OpenStreetMap), along with vectorising and highlighting the map’s key components. Analysis of documents from the Central State Historical Archives of Ukraine in Lviv helped identify the plot numbers that were common right areas. The map created shows that almost all the court forests and pastures served as common right areas for grazing village cattle. This was remarkably rare; in other parts of Galicia, specific, much smaller court properties were designated. Further analysis of the sources explains how this situation arose in Nowa Grobla. Compared to other settlements, the peasants did not have many cattle, but the area of forest and pasture within the village borders was large. Moreover, given the poor-quality soil, limiting cattle grazing to a smaller site would have led to the destruction and degradation of the flora.

Figure 1. Forest, meadow, and pasture common areas in Nowa Grobla. Created by the author in QGIS 3.4.4.

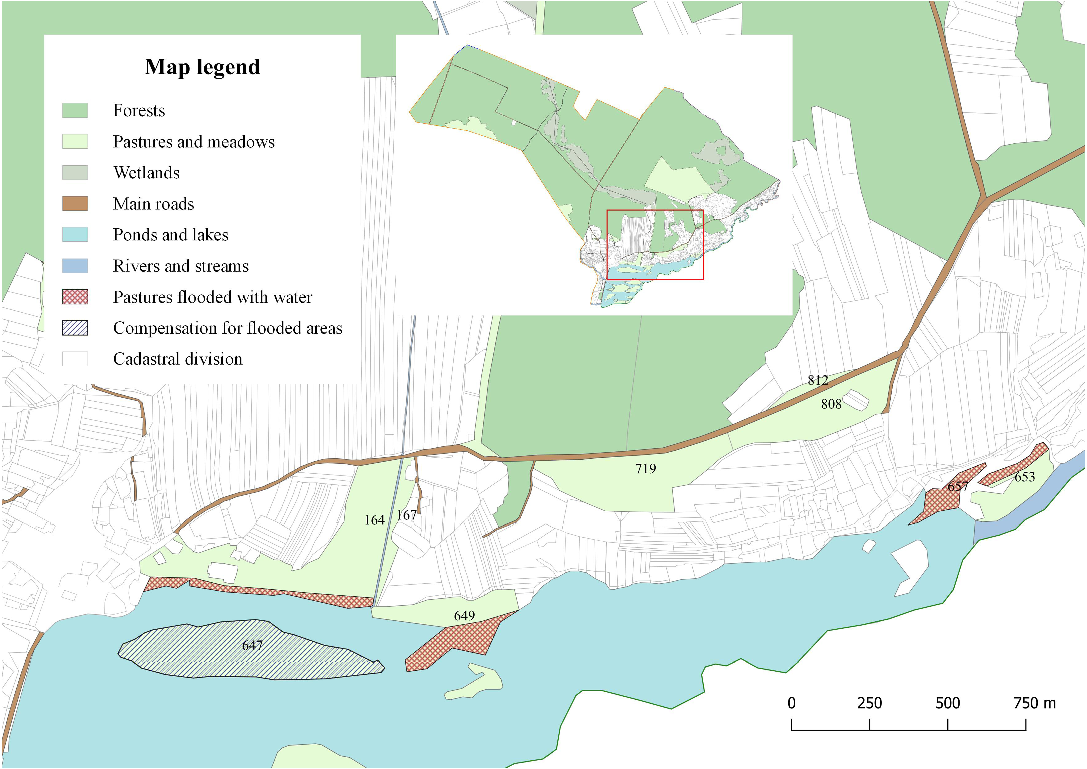

As part of compensation for their abolished right to graze cattle, the peasants were supposed to receive the equivalent of the pastures, separated from the court lands. Considering the poor-quality soil, which was often flooded, the court tried to give the village the poorest quality area of its property. The village plenipotentiaries were aware that, despite the large area of the pastures offered, they would not be of much use for grazing cattle. They demanded that all the commission’s members go to the designated place and assess the quality of the pastures themselves. The peasants’ efforts brought the desired effect: both the commission and the experts found that the land proposed by the court was of poor quality and often flooded by the nearby lake and rivers. As a result, the village received over a dozen more morgens of land in compensation. Eventually, by mutual agreement of the parties, the local commission decided that eligible farmers would receive a total of 186 morgens and 1,383 fathoms encompassing plots 1533, 1532, 812, 808, 719, 657, 653, 649, 167, and 164 (as shown in Figure 2) for the abolished grazing right.Footnote 66

Figure 2. Pasture equivalents granted to peasants from Nowa Grobla as compensation for the abolished right to graze cattle in court forests and pastures. Created by the author in QGIS 3.4.4.

Figure 3. Peasants’ flooded pastures in Nowa Grobla, alongside compensation received, in 1864. Created by the author in QGIS 3.4.4.

That was not the end of the conflict, though. A few years later, due to rapidly melting snow in the spring, the court administration was forced to raise the level of water in the pond. This led to the flooding of some of the pastures that the village received as compensation for the abolished right to graze cattle. The peasants deemed this deliberate action by the court and demanded compensation. The local commission for common rights ruled on the matter in 1860. At the first session, the appointed experts indicated that it was only a matter of time before the pastures beside the lake were flooded. As a result, the peasants’ grievances were justified, and the court was obliged to provide compensation. The commission’s final ruling was accepted by both parties. The village received an island in the lake [plot number 647] in compensation, equivalent to a pasture with an area of eight morgens (as shown in Figure 3).Footnote 67

IV

Conflicts over common rights to cattle grazing were common in nineteenth-century Austrian Galicia. They were part of the vital conflict of interests and the different aspirations among the key social groups. The disputes discussed in this article were not the only ones. The rich archival documentation contains many other examples that cannot be traced in detail in an article of this length. Nevertheless, the selection of a representative group of sources shows the most common disputes over common rights to cattle grazing in court and common forests, pastures, meadows, fallow land, and wasteland. The extremely important role played by common rights to cattle grazing in the modernisation of the entire province is undeniable. All kinds of conflicts slowed down development, while the need to abolish and regulate rights was beyond discussion. The abolition of common rights to cattle grazing, which resulted from the subordinate relationship as a relic of the feudal system, was a necessary requirement on the path to modernisation that brought many benefits.

The forests could be managed in a planned and responsible way, preventing the degradation of vegetation. In society, abolishing numerous archaic economic arrangements improved difficult relations, especially between the court and the previously subordinated population. The proceeding abolition of rights in the second half of the nineteenth century, combined with the division of common land, was not accompanied by other desirable agrarian reforms, such as ending the so-called chessboard: the massively extensive fragmentation of land. The ‘reparcelling’ of farmland did not take place until the end of the nineteenth century and did not produce measurable results until the outbreak of the First World War.Footnote 68

The formal work of the commissions settling disputes linked to common rights ended in 1895 and their powers were taken over by law courts. Summary data shows that, by then, the commissions had conducted a total of 30,733 inquiries concerning all the forms of common rights resulting from the former relationship between sovereignty and serfdom. Of these, just 30 per cent or so ended with an agreement between the parties. The other disputes were resolved with rulings by the commissions and central bodies, or the law courts. In most cases, peasants, townspeople, and clergy received the equivalent pastures, arable fields, and meadows separated from court property as compensation. In total, 116,452 morgens and 83 fathoms were transferred.Footnote 69

Acknowledgements

This article arose from the research project: ‘The Conflicts of Easements in Galicia in the Second Half of the 19th Century. The Process of Redemption and Regulation of Easements in the Area of Middle Galicia’, as part of the SONATINA 1 competition (No. 2017/24/C/HS3/00129) funded by Poland’s National Science Centre.