South Africa has a dual health system in which the majority of the population is covered by the public health care sector and 16% of the population with higher incomes is covered by voluntary private health insurance delivered through medical schemes. Medical savings accounts (MSAs) were first introduced by medical schemes in 1994 and their usage grew rapidly in the first decade but declined in the second decade. By 2005, MSAs covered 88% of open scheme beneficiaries and 49% of restrictedFootnote 1 scheme beneficiaries but by December 2014 MSA coverage had declined to 67% of open scheme beneficiaries and 18% of restricted scheme beneficiaries. This chapter focuses on MSAs, but more information on medical schemes and private health insurance can be found in Chapter 12 in this volume.

Factors that fostered the development of MSAs

The increasing involvement of insurers in the health care market in the late 1980s resulted in calls for greater individualization of health care expenditure. This was in line with life insurance and retirement designs, which at the time moved towards individualized accounts and away from pooled risk. Chapter 12 deals in more detail with the free-market reforms of the private health insurance market in the late 1980s that culminated in the abolition of community-rated premiums in 1989 and the abolition of minimum benefits in 1993. The democratic government, newly elected in 1994, therefore inherited a system that had turned substantially in the direction of private insurance principles, with members being charged premiums based on their age and state of health.

In 1993, immediately before South Africa’s transformation to democracy, the Melamet Commission reported on the status of medical scheme regulation. The Commission warned that the industry’s regulator was woefully inadequate to supervise it appropriately. At that time, the office of the regulator consisted of the Registrar and seven staff, one of whom was the secretary and none of whom had any tertiary academic qualifications. This group was supposed to supervise an industry with some 230 different schemes and multiple options within them.

The history of personal MSAs dates from this period of lack of regulation. MSAs were first introduced by Discovery Health Medical SchemeFootnote 2 in 1994.Footnote 3 There was no intervention from the regulator and other schemes rapidly followed suit. The 1990s were a period of rapid innovation by insurers and the role of savings accounts and their influence on benefit design and risk selection is discussed here in more detail.

From a policy perspective, the 1990s was a period of regulatory efforts leading to a completely revised Medical Schemes Act, No. 131 of 1998, which came into effect in January 2000. The Act allowed for the formation of a new independent regulatory body, funded by the industry and with access to legal, accounting and actuarial expertise. The Act also began to substantially roll back the freedom to operate that insurers and the MSA movement had seized in 1994.

The key elements of the Medical Schemes Act of 1998 were the introduction of open enrolment and the re-introduction of community rating and minimum benefits. There was increased protection for members changing schemes, but schemes were also given some protection against adverse selection as they were allowed to apply waiting periods to members switching schemes. The Act significantly strengthened the governance of the industry through the introduction of the new Council for Medical Schemes, which was tasked with looking after the interests of beneficiaries of medical schemes (the first Medical Schemes Act of 1967 required the Council to look after the interests of the schemes, see Chapter 12). The Council began to operate in 2000 with the appointment of a new Registrar and senior staff. The governance of schemes was also strengthened with provisions for increased independence of the Board of Trustees from the administrator and other advisors.

The introduction of MSAs in the 1990s

A paper setting out the basic tenets of MSAs was written in 1993 by Adrian Gore, an actuary and the entrepreneurial founder of a leading health insurance group, Discovery Health.Footnote 4 Gore argued that with the planned deregulation, the environment was about to be freed up “to test virtually every known cost containment technique in the financing of health care” (Gore, 2003). He argued strongly in favour of individuals becoming the principal buyers of health care with opportunities to compare options and prices in order to facilitate their decisions. Gore described a conceptual framework for personal MSAs under which members would make deposits to their personal accounts, which would be used to pay for smaller day-to-day medical expenses such as consultations, medicine and spectacles. Rather than a “use-it-or-lose-it” mentality, these savings accounts would encourage careful purchasing and unused balances would be rolled over to future years. Major and catastrophic medical expenses like hospitalization would still be paid from the risk pool.

Reference GoreGore (1993: p.147) argued that the establishment of MSAs “is a movement in the direction of a worthwhile social goal: making all employee benefits personal and portable”. In his opinion, MSAs would lower the cost of health care (Reference GoreGore, 1993: p.145): “The use of Medical Savings Accounts institutes the only cost containment system that has ever worked – members avoiding waste because they have a financial interest in doing so. When members are spending money on medical goods and services, in effect they are spending their own money, not someone else’s – an excellent incentive to buy prudently.” He concluded by saying that: “In our opinion, the results will be better if we follow the individualistic vision of health care wherein people bear the costs of their bad decisions and reap the benefits of their good ones. A choice must be made between health care and other uses of money; as often as possible these choices should be made by individuals.” (Reference GoreGore, 1993: p.156).

Reference JostJost (2005) found that the development of MSAs in South Africa was encouraged by John Goodman, president of a United States MSA advocacy group, the National Center for Policy Analysis, who worked with Discovery Health in developing the concept. Subsequent papers by Discovery Health executives on the experience of savings accounts in South Africa were published by the National Center for Policy Analysis (Reference MatisonnMatisonn, 2000, Reference Matisonn2002). Attempts by Discovery to export the savings account concept to the Unites States through a subsidiary, Destiny Health, have been less successful than at home. Discovery Health and its associated medical scheme have been perceived as market leaders in benefit design and industry practice since their launch in 1993. The market-oriented reforms of 1993 were among the last actions of the apartheid government. Discovery Health Medical Scheme took advantage of the new freedom to design benefits and introduced personal MSAs in 1994. This innovation was rapidly copied by other schemes, particularly those in the very competitive open schemes market.Footnote 5

The South African private health insurance environment is highly competitive and, with the lack of regulatory oversight, a number of practices emerged in the 1990s that caused concern to researchers and policy-makers. The use of brokers and reinsurance was encouraged by the prevailing insurance mentality of the 1990s, and aggressive underwriting of entrants and claims became widespread.

The Department of Health (2002) found that by 1999 no open scheme was permitting anyone over the age of 55 to join as an individual member. Lifetime exclusions for pre-existing conditions as well as age rating and experience rating occurred without restriction. Thus the majority of medical scheme members were in an environment that excluded vulnerable groups from cover, where medical costs continued to rise (because fee-for-service reimbursement was maintained) and where non-health care costs were driven up (through profit-taking and hidden commission costs).

At the time of the conceptual development of MSAs, Reference GoreGore (1993) had noted that medical expenses paid by employers provided benefits effectively paid with pre-tax money, whereas expenses paid by members themselves were paid from after-tax money. He argued that “properly structured Medical Savings Accounts provide the perfect solution in that members effectively pay for their own medical expenses with pre-tax money” (Reference GoreGore, 1993: p.147).

Brokers and employers rapidly used the new structures to create tax breaks for employees and more money flowed to medical schemes. Initially there was no limit as to the amount an employer or employee could contribute to the MSA. Employees could opt to take part of their salary increase in the form of pre-tax payments to the MSA. Some employees took their entire salary increase in this form and were able to build up significant MSA balances.

Reining in MSAs from 2000 onwards

The Medical Schemes Act of 1998, implemented from January 2000 onwards, closed the tax loophole by limiting the amount that could be paid to MSAs to 25% of annual medical scheme contributions. The newly strengthened Council for Medical Schemes was able to moderate increases in non-health care costs and dampen the excesses of benefit design by introducing regulations that would enhance, rather than reduce, the pooling of health expenditure (for these and other key developments in the MSA market, see Box 13.1).

Box 13.1 Key developments in benefit design and the market for medical savings accounts in South Africa, 1986–2016

This box should be read in conjunction with Chapter 12, which describes key developments in the broader South African health care market.

1986 to 1994: Free market reforms

Browne Commission supports the application of risk rating and experience rating by medical schemes, as well as the individualization of health care expenditure. Differentiation of benefit packages is encouraged, allowing people to choose according to their needs and permitting the schemes to charge according to the risk of those choosing the package. Insurers argue and the Commission concurs, that there would be significant cost savings if members paid small claims themselves and only claimed from pooled funds thereafter (1986).

Amendment to Regulation 8 of the Medical Schemes Act of 1967 allows contributions to be determined according to risk (1989).

Medical Schemes Amendment Act, No. 23 abolishes guaranteed minimum benefits (1993).

Actuarial Society of South Africa publishes key paper by Adrian Gore on the rationale for MSAs (1993).

Melamet Commission is established under the old political regimen and reports immediately before transition to a democratic government. Dismal state of regulatory supervision is highlighted and recommendations are made for an independent statutory regulatory body (1993–1994).

1994 to 2000: Preparation for re-regulation under the democratic government

Discovery Health creates first health plan with personal MSAs (1994).

African National Congress Health Plan of 1994 is published and principles are established for moving to social health insurance (1994).

The philosophical direction that was recommended by the Melamet Commission is rejected and replaced by a strategic direction from the 1995 National Health Insurance Committee of Inquiry (1995).

Completely revised Medical Schemes Act, No. 131, of 1998 reinstates open enrolment, community rating and prescribed minimum benefits. Substantially strengthened regulatory supervision is enacted. Contributions to MSAs are limited to 25% of total medical scheme contributions (1998, implemented from January 2000).

2000 to 2008: Preparation for social/national health insurance

Legislative amendments are made to clarify savings account legislation: accumulation of unexpended benefits can only be done under savings account regulations; minimum benefits must be covered from risk pool and not from savings accounts; credit balances can be transferred to another option within the same medical scheme or another scheme if the new option or scheme has an MSA; if the new option or scheme does not have an MSA, the balance can be paid out but will be subject to tax (2002, effective January 2003).

Formula Consultative Task Team designs and obtains industry consensus on the formula for risk equalization between schemes (2004).

International Review Panel argues that benefit designs should be standardized and simplified to improve competition (2004).

Minimum benefits in medical schemes are extended to cover diagnosis, treatment and medicine for 25 common chronic conditions (2004).

Circular 8 from the Council for Medical Schemes argues that common benefits should in the future be paid from a single risk pool. Due to the lack of industry agreement these ideas have not yet been implemented (2006).

Council for Medical Schemes applies to the High Court for a declaration on status of savings account balances. There had been concerns that savings account balances could be seized by creditors in case of insolvency. However, the courts confirmed that these balances belong to members in the event that a scheme is wound up or liquidated, that is, individual MSAs are protected in case of the medical scheme’s bankruptcy (2006).

Medical Schemes Amendment Bill of 2008 provides for establishment of a Risk Equalization Fund to be managed by the Council for Medical Schemes in order to set up a framework for paying risk-adjusted amounts to medical schemes (Republic of South Africa, 2008). Legislation prepared for Parliament in 2008 but allowed to lapse and not re-submitted. The possibility of a new national health insurance system that might impact on the medical schemes’ environment was the cause of the legislation not being dealt with in 2008, after a resolution to introduce national health insurance was taken in December 2007 by the ruling party.

2008 to 2016: Reform at the margins and waiting for national health insurance

South African government publishes a Green Paper in 2011 outlining proposals for a single-payer national health insurance arrangement as a means to achieve universal health coverage, followed by a White Paper in 2015 (Reference van den Heevervan den Heever, 2016). All financing and purchasing would occur nationally through a new National Health Insurance Authority and medical schemes would no longer provide substitutive cover, although some voluntary supplementary cover may be allowed to continue. Arguments between the Department of Health and National Treasury on the affordability of the proposals have not yet been resolved but the lack of progress on NHI and the lack of a clear proposal for the future role of medical schemes means that further medical scheme legislation has been stalled since 2008. Plans to introduce risk equalization between schemes and to allow some form of low-cost option are therefore stalled.

Council for Medical Schemes allows efficiency-discounted options to be created from 2008 onwards. Efficiency-discounted options are benefit options with network arrangements for health care provision. They allow medical scheme contributions to be differentiated on the basis of the health care providers that are used to provide benefits. Rather than create new legislation, the Council allows schemes to be exempted from Section 29(1)(n) of the Medical Schemes Act, which stipulates that contributions may be differentiated only on the basis of income or family size, or both.

Council for Medical Schemes issues two circulars on the accounting treatment of MSAs and interest earned on MSAs (Circular 38 of 2011 and Circular 5 of 2012). The schemes were forced to pay interest at the rate earned on the underlying funds. Previously most schemes did not charge interest on any upfront MSA provided but also did not pay interest on positive balances or paid a very low rate. As interest could still not be charged on the upfront MSA, MSAs in effect became a cost to schemes. Schemes also have to invest the MSA balances separately and account for MSAs more transparently than before.

Council for Medical Schemes rejects (2013) the Genesis Medical Scheme’s 2012 annual financial statements on the basis that these statements understated the scheme’s financial position by excluding the members’ personal MSAs from its liability. In the view of the Council, this money belonged to the members and not to the scheme. Genesis took the matter to the High Court which subsequently ruled in its favour. Later, the Supreme Court of Appeal ruled in the Council’s favour (2015), but on further appeal, the Constitutional Court ruled in favour of Genesis (2017). This judgement overturns the understanding that MSA balances belong to members and are protected in the event of the scheme becoming insolvent.

Highly competitive medical schemes reacted to the re-introduction of community rating, open enrolment and minimum benefits in 2000 by attempting to find ways to continue risk rating. Early attempts by some of them to combine medical schemes with insurance productsFootnote 6 (sold under different legislation with high commissions, underwriting and risk rating allowed) were rapidly dealt with by the new regulator in 2000. Other abuses, such as paying brokers to attract only young members, were also quickly made illegal.

More subtle were the attempts to get around the community rating through benefit design and marketing practices. Discovery Health again led the market in creating incentive and wellness programmes similar to the frequent-flyer programmes used by airlines. Points were initially earned for gym visits and preventive care but later could also be earned from loyalty programmes, for example by using the Discovery group credit card. Points can be redeemed for low-cost airline tickets and other shopping rewards. Although this wellness programme (called Vitality) was technically outside the non-profit medical scheme, many consumers saw this as a medical scheme initiative. Many other medical schemes have followed their lead but a few have begun to make a feature out of being involved only in purchasing health care for their members, refraining from offering incentive and wellness programmes.

To escape the provisions limiting contributions to MSAs to 25% of total medical scheme contributions, schemes developed innovative new structures. One example of such a structure was to pay the benefits from the risk pool but to create an entitlement to the rollover of unexpended benefits to the next year. A legislative amendment effective from 2003 ensured that individualization of benefits could only be done under the provisions for MSAs. Other aspects of savings account administration were also clarified.

Of particular concern was the fact that minimum benefits (prescribed by regulations) were being paid from savings in some cases and the revised legislation made it clear that minimum benefits were to be paid from the risk pool. The design of the Risk Equalization Fund will further entrench the use of the risk pool to pay minimum benefits. Only amounts paid from the risk pool will count towards proving that a person meets the treated patient criteria for a chronic disease.

Fig. 13.1 illustrates generic benefit design by the end of the first decade of MSAs in South Africa. Initially, MSAs were used to pay almost all of the day-to-day benefits. Above-threshold benefits were introduced to assist those members who had higher day-to-day expenditure than their annual savings allocation. Access to pooled benefits required that the MSA was exhausted and that expenditure had been on items deemed by the medical scheme to be allowable.Footnote 7 When the size of MSAs was restricted in the Medical Schemes Act of 1998, many schemes developed a pooled lower tier such as the annual routine benefits. Some schemes require a self-funding gap between the MSA and the above-threshold benefit. Increasing this gap is a way to mask increases in the price of medical scheme contributions as the larger the gap, the lower the cost of the above-threshold pooled benefit.

Figure 13.1 Generic benefit design in medical schemes in South Africa in the mid-2000s

Variations in the generic benefit design continued to emerge as schemes attempted to evade the regulatory restrictions. As the amount that could be paid to the savings schemes was decreased by legislation, annual routine benefits were introduced. This was legally a portion of the pool but created a notional amount available for expenditure by the family at the discretion of the member, as if it were a balance on a savings account. Unused money at year’s end reverted to the pool, although some variations initially attempted to hold this amount over for the member, contravening the legislation. Variable savings accounts had become widespread in the early 2000s as schemes allowed members to determine how much they wanted to put in savings themselves, so creating an almost infinite variety of contribution levels for the same option. The regulator saw them as a means of risk rating members because part of the contribution paid by members reflected their health needs. The Medical Schemes Act specifically prohibits contributions being set according to the state of health of the beneficiaries.

While medical schemes tried ever-more innovative ways to attract members, the regulator, the Council for Medical Schemes, argued for simplification and standardization of benefit structures (CMS, 2005). The regulator increasingly tightened the annual process of registering benefit design changes. A directive was sent to the medical schemes in 2005 on the use of annual routine benefitsFootnote 8 and variable savings accounts. Over several years, annual routine benefits disappeared from medical scheme designs, as the Registrar insisted that schemes must start payment of day-to-day benefits from the MSA first before using any benefits from the risk portion. From 2006, the Council for Medical Schemes insisted that variable savings account levels needed to be registered as separate options. As a result, medical schemes rationalized their savings account plans, typically by creating one option with an MSA and another without.

Government Employee Medical Schemes with an alternative to MSAs from 2006 onwards

The period from the introduction of MSAs in 1994 through to the end of 2005 was one in which Discovery Health Medical Scheme dominated the South African medical scheme market, both in terms of innovation and in growth of the numbers of beneficiaries. Fig. 13.2 shows the split between the numbers on open and restricted schemes in South Africa and the rising dominance of Discovery Health Medical Scheme.

Figure 13.2 Number of beneficiaries in open and restricted medical schemes in South Africa, 1997–2015

A major disrupter to the MSA market was the registration of the Government Employees Medical Scheme (GEMS) in January 2005, which became operational in January 2006 (see Chapter 12 for the rationale on the introduction of GEMS).

As shown in Fig. 13.2, GEMS grew rapidly from 2006 at the expense of open schemes other than Discovery Health. Government employees that had previously used their medical scheme subsidy in the open market increasingly moved to GEMS, and new public sector employees were required to move to GEMS. In a short space of time, GEMS became a role model for other medical schemes in terms of benefit design (Reference McLeod, Ramjee, Harrison, Bhana and NtuliMcLeod & Ramjee, 2007). GEMS did not develop any MSA options but rather focused on provider network restriction and using the bargaining power of the scheme.

While MSAs are still available in South Africa, the competition provided by GEMS was a significant factor in reining in the use of MSAs to attract members. Although MSAs are described as a benefit in medical scheme marketing material, it has always been the case that members pay for MSAs from their own money (Reference Kaplan and RanchodKaplan & Ranchod, 2015).

In a study in 2013 on open scheme benefit design, Kaplan and Ranchod found a very wide distribution of the size of MSAs marketed, with the maximum per annum savings level for a one adult, one child family to be 54 times that of the minimum savings level offered (Reference Kaplan and RanchodKaplan & Ranchod, 2015).

Contribution increases in medical schemes continue to be at levels in excess of wage inflation, adding to the unaffordability of private health insurance for many. MSAs have at times been used as a buffer in presenting increases to the highly-competitive open market. An overall increase to the member can be artificially made to seem smaller by not increasing the MSA portion at the same pace as the risk pool contribution.Footnote 9

Over time, this means that the total proportion of medical scheme benefits paid from savings has declined from the peaks of the mid-2000s. In 2005, MSAs accounted for 11.7% of total benefits (CMS, 2006a, 2014, 2016) but by 2013 the proportion had declined to 9.7%. By the year 2015 with restrictions on the size of risk pool increases and a reversal in the growth of GEMS, MSAs accounted for 10.1% of total medical scheme benefits paid.

Given the greater use of MSAs in open scheme design, 14.5% of benefit expenditure in open schemes was from MSAs, compared with 4.0% in restricted schemes.

Benefit design and MSAs as a tool for risk selection

Reference McLeod, Ramjee, Harrison, Bhana and NtuliMcLeod & Ramjee (2007) explain that benefit design fulfils three (sometimes conflicting) functions for a medical scheme. Benefit design decisions influence the marketability and competitiveness of a scheme, the extent of risk pooling within a scheme, and the manner in which benefits are rationed and delivered. The emphasis differs considerably between open schemes and restricted membership schemes, largely due to the differences in competitive dynamics. In a community-rated environment without a Risk Equalization Fund, open schemes with a lower risk profile will be more competitive. There is therefore a strong incentive to use benefit design to “cherry-pick” healthy members.

In the absence of risk equalization mechanisms, the regulatory challenge shifts to limiting the extent to which schemes can use benefit design to select members and influence their risk pool. The minimum benefit package defined for use in 2000 was interpreted by many schemes to exclude out-of-hospital coverage of chronic conditions. Some schemes substantially reduced chronic medicine benefits to be less attractive to older and less healthy members. The minimum benefit package was revised with effect from January 2004 to include diagnosis, treatment and medicine for 25 defined Chronic Disease List conditions.

In 2014, more than 60% of all restricted schemes have only one option whereas all open schemes, in attempting to provide a wider choice for competitive reasons, have multiple options. Open schemes typically offer four to six options but some offer many more, with Discovery Health Medical Scheme offering 15 options in 2014, 12 of which have MSAs. Open schemes use the higher number of options to steer members with similar risk profiles to particular options, which negates risk pooling.

Benefits for chronic conditions remain an effective tool for differentiating between the options and hence for risk selection. Schemes have moved away from providing chronic cover in excess of the Chronic Disease List, with even comprehensive options moving away from completely open disease lists. Some schemes use a higher level of self-funding through MSAs for non-Chronic Disease List diseases.

Without the competitive pressures that open schemes are subject to, restricted schemes have historically been able to provide more generous chronic benefits. Restricted schemes make more use of the cross-subsidies between young and old members in the same option and in this way can offer more extensive benefits for chronic conditions for the same community rate contribution.

There has been a long-term shift in medical schemes away from funding primary care towards funding major medical benefits (hospitals and specialists, together with the Chronic Disease List chronic diseases). Major medical expenditure accounted for only 42.5% of pooled funds in 1974 but it had risen to 71.4% by 2005. This shift has been driven partly by the strong increases in hospital expenditure and the shifting of out-of-hospital expenses to MSAs, and is underpinned by the minimum package emphasis on major medical benefits from the implementation of the Medical Schemes Act of 1998.

The increases in hospital expenditure have led to an increasing use of deductibles by schemes as a means of discouraging elective hospital admissions and some expensive diagnostic procedures. Deductibles are inherently regressive in nature and have an adverse effect on affordability for low-income members.

Operation of MSAs

While the terminology medical savings accounts has been applied to examples from Singapore, China, South Africa and the USA, the details of how the accounts function are often subtly different. Reference MatisonnMatisonn (2000) explains the US model as a single deductible across all benefits with a savings account to cover expenditures below this deductible. In South Africa, Prescribed Minimum Benefits (PMBs) have an important impact on the use of MSAs. Treatment falling under the PMBs (about half of all expenditure) must be covered in full with no co-payments (similar to the so-called first-dollar coverage in the USA).

The MSAs in South Africa are typically used for day-to-day benefits like doctors’ visits, basic radiology and pathology. The initial design suggested that all prescription medicines could be included but subsequent changes to competitive designs and legislation have meant that only acute prescription medicines are typically covered with chronic prescription medicines and other major medical expenses covered in the risk pool. MSAs are used almost exclusively for outpatient care but could be used to pay for inpatient care not covered as a minimum benefit (PMBs) or by the risk pool. Spending from an MSA is not restricted but if the option has an above-threshold benefit (see Fig. 13.1), there will be restrictions on what savings expenditure is counted towards reaching the threshold. The distinction between actual MSA expenditure and allowed expenditure adds a further layer of administrative complexity and is confusing to members.

Regarding the benefits of the medical schemes, to the extent that a person does not use the designated service provider, network or drug formulary, they may be liable for the difference in cost compared with the PMBs. Initially this could be paid out of pocket, or the MSA was used to pay the difference. However a strict interpretation of the Medical Schemes Act requires that PMBs may not be paid from savings and the Council for Medical Schemes has taken a stricter line on this since the early 2000s. Members may no longer use their MSAs to pay for any shortfall on a PMB event as the Council wants PMBs to be fully covered by pooled funds. PMBs typically cover about 55% to 60% of all in-hospital expenditure. MSAs can be used to cover benefits not covered by the health plan, such as complementary health practitioners, nonformulary medicines, corrective eye surgery or cosmetic surgery.

The MSAs are set up at the member level, that is, the principal member that joins the scheme. This means that the account can be used freely across any covered family member. The schemes quote the total contribution needed but some members may be supported by an employer. The split between employer and employee is the subject of negotiation in the workplace and is of no consequence to the medical scheme. Hence the total contribution, irrespective of how it is split between employer and employee, is credited to the member. The amount for the savings account is then allocated and there is no cognisance of whether the amount came from the employer or employee.

Contributions to the MSA are payable monthly, usually at a fixed level set at the beginning of the year by the medical scheme for each benefit option. Many medical schemes allowed members to draw up to 12 times that level at any time during the year, effectively making a loan to the member. If interest is paid on balances, it should also be charged on the loans. Interest rates paid on balances were usually less than commercial rates and the difference was kept by the scheme until regulation in 2011 and 2012 (see Box 13.1). Some schemes had opted to simplify administration by neither paying nor charging interest; some levied a specific MSA administration fee but it was more likely to be hidden in the overall administration fee for that option.

The MSAs form part of the medical scheme’s pool of investment funds. A large part of schemes’ investments are in cash and near-cash instruments and the funds are rarely invested separately from the MSAs. In general the administration of savings account balances had been poor and the regulator introduced changes in 2011 and 2012 (see Box 13.1). Solvency is calculated as a fixed percentage of the gross contributions (risk pool and MSA portion). This makes for inequity between schemes as if there are two identical schemes in all regards, except that the one has an additional MSA, they have to hold different reserve levels. Both these schemes have the same underlying risk but require different levels of reserves to be held for solvency. The introduction of some form of risk-based capital could improve this but discussions have been underway with the industry since 2004.

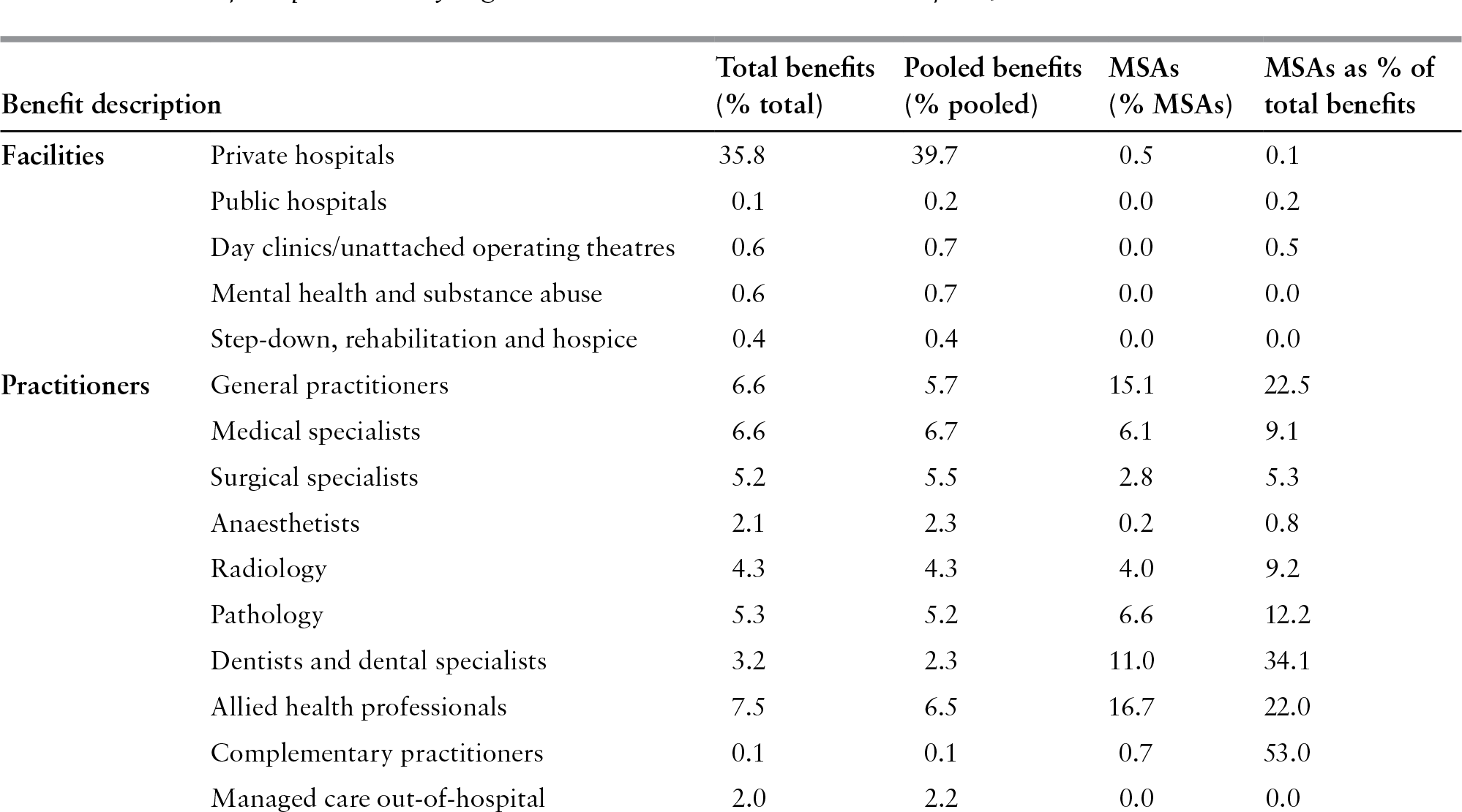

Table 13.1 Benefit expenditure by registered medical schemes in South Africa, 2014

| Benefit description | Total benefits (% total) | Pooled benefits (% pooled) | MSAs (% MSAs) | MSAs as % of total benefits | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilities | Private hospitals | 35.8 | 39.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Public hospitals | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | |

| Day clinics/unattached operating theatres | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| Mental health and substance abuse | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Step-down, rehabilitation and hospice | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Practitioners | General practitioners | 6.6 | 5.7 | 15.1 | 22.5 |

| Medical specialists | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.1 | 9.1 | |

| Surgical specialists | 5.2 | 5.5 | 2.8 | 5.3 | |

| Anaesthetists | 2.1 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 0.8 | |

| Radiology | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 9.2 | |

| Pathology | 5.3 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 12.2 | |

| Dentists and dental specialists | 3.2 | 2.3 | 11.0 | 34.1 | |

| Allied health professionals | 7.5 | 6.5 | 16.7 | 22.0 | |

| Complementary practitioners | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 53.0 | |

| Managed care out-of-hospital | 2.0 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Medicines | Medicines dispensed by pharmacists | 14.7 | 12.7 | 33.1 | 22.2 |

| Medicines dispensed by all practitioners | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 14.5 | |

| Other | Ambulance | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Blood, oxygen and technology | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | |

| Other benefits | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 3.2 | |

| Ex gratia payments | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 9.9% | |

Source: Based on CMS (2016).

In accounting terms, the MSA balances had been viewed as a liability rather than an asset as the understanding was that they belonged to the members and not to the scheme. The status of members’ savings account balances has been subject to legal disputes since 2013 (see Box 13.1). In 2017, the Constitutional Court ruled that funds in medical scheme members’ personal MSAs can be treated as assets of a medical scheme, rather than as liability. The implications of this ruling have not yet been worked through in terms of solvency calculations. It seems likely that the ruling may result in reduced attractiveness of MSAs to members and hence to lower use of MSAs in future. The Council for Medical Schemes may need to introduce new regulations to cover the preferred treatment of savings as belonging to members.

The balance on the MSAs is carried over from year to year and can only be withdrawn when a person leaves the medical scheme to join a scheme without an MSA or moves to another option that does not have an MSA. The withdrawal of the MSA balance is taxed as income in the hands of the member. On death, the balance will be transferred to the surviving spouse or child who becomes the new principal member. If there are no dependants, the balance will form part of the deceased member’s estate.

Payments are made from the MSA directly to the health care practitioner who submits a bill to the medical scheme for the service rendered. Health care practitioners have found MSAs to be problematic in terms of their cash flow as they might render a service only to find out that the MSA had been exhausted when they submit the bill. Schemes responded by providing doctors and pharmacists with access to information on MSA balances via electronic terminals, allowing them in some cases to immediately reserve a portion of it for future claims. This gave doctors and pharmacists the certainty that the savings account was in positive balance at the time the service was purchased and that they would receive payment for the service rendered. Some schemes have experimented with smart cards that hold details of the MSA balance, others have linked up with banks to provide card facilities similar to a debit card. Discovery Health Limited at one stage offered credit at First National Bank, a bank in the same financial group, when the MSA was exhausted. MSAs have increasingly fallen out of favour with the health authorities and the medical schemes regulator, who see MSAs as resembling banking accounts.

Benefit expenditure from savings accounts

Table 13.1 shows the total expenditure by medical schemes in 2014 on various services, split into pooled benefits and MSAs. Expenditure from MSAs is concentrated on out-of-hospital care. While MSAs are used for less than 0.5% of private hospital expenditure, nearly a third of visits to dentists and dental specialists are paid from MSAs. Some 20–25% of visits to general or family practitioners and medicines are paid from MSAs. This understates the amount of out-of-pocket expenditure as the doctor may be paid directly rather than by submitting the bill to the medical scheme to be paid from the savings account. In total, 9.9% of benefit expenditure in 2014 was from MSAs (Fig. 13.3).

Figure 13.3 Personal medical savings account expenditures in South Africa by benefit category, 2014

The savings balances held on behalf of members and carried over from 2015 to 2016 amounted to 11.1% of total assets of medical schemes in 2015. To put this in context, the savings balances carried over were equivalent to 51.3% of total MSA contributions in 2015.

Policy concerns about MSAs

The Department of Health does not view MSAs in a positive light; it has long argued that the justification for MSAs is very limited and that all evidence suggests that they are counter-productive (Department of Health, 2002). A major concern is the effect on reducing risk pooling in medical schemes. The Department of Health found no objective evidence that self-insurance reduces the cost trends of necessary medical services and argues that costs will only be contained by strategic purchasing of services covered by the risk pool. Services paid for from MSAs are effectively purchased by individuals, further fragmenting purchasing power and potentially allowing providers to charge even higher fees for such services. This could ultimately translate into greater financial access barriers to health care.

Although high administration fees have been under scrutiny by the regulator, additional charges of more than 10% of the saved amounts were at times levied for managing the savings accounts. The reconciliation of individual entitlements and interest accrued and charged was not transparent before regulatory changes in 2011 and 2012 (see Box 13.1). The Department of Health is of the view that as MSAs are essentially personal savings of an individual, many individuals are likely to be financially worse off by putting their money into an MSA rather than placing them in their own personal bank account. The ruling that MSA balances belong to the scheme and not the members (see Box 13.1) would make MSAs even less attractive.

The Department of Health (2002) concluded in 2002 that:

“Medical savings accounts are clearly problematic in a number of important policy goals and from the consumer protection perspective. It is therefore recommended that the current policy be revisited with a view to phasing them out of medical schemes, or at least substantially diminishing their impact on risk pools and contribution costs. The focus of health policy needs to be on risk-sharing and cost containment and none of these key health policy objectives can be achieved through medical savings accounts.”

The Council for Medical Schemes (2006b, 2007) expressed concern about the increased risk-shifting to members through the use of savings accounts. However, while the environment remains voluntary, there is a delicate cross-subsidy from the young to the old in private insurance schemes. There has therefore been a reluctance to remove MSAs completely because that might encourage the young and healthy to leave the system. This may be changed following the 2017 ruling (see Box 13.1).

Evidence for risk selection by MSA plans

The MSA issue generates heated arguments and it is difficult to find objective and independent evidence on the impact of MSAs. Reference JostJost (2005) found that most of the material available in Europe and the USA on the South African experience was written by one executive from Discovery Health. These documents, used for lobbying for consumer-driven health care in the USA, deliberately imply a high level of government support for the MSAs,Footnote 10 whereas South African government policy has in fact been completely the opposite.

A major independent study of risk in South African medical schemes (RETAP, 2007) was carried out using 2005 data from the four largest administrators, who provide services to 63.4% of the private health fund beneficiaries in the country. The risk factors used were those identified for use with the Risk Equalization Fund, namely age, gender, maternity events, chronic diseasesFootnote 11 and multiple chronic conditions.Footnote 12 It was found that there were substantial differences in age profile between different product types in open schemes. Network plans that require the member to obtain all primary care through a network of capitated providers were, at the time, a recent initiative and were marketed primarily to low-income workers. Plans with network options covered only had a very young age profile whereas those members who had a choice of benefit design and chose a non-MSA option were found to have an older age profile. The surprising finding in the study was that all benefit types had a similar rate of incidence per 1000 of chronic disease and multiple chronic diseases by age band. In other words, there was no evidence that choice of a savings account leads to the selection of more healthy members, after adjusting for the effects of age.

Assessment of market performance

Financial protection

Although the motivation for introducing MSAs explicitly stated by the medical schemes was to reduce moral hazard and to promote more restrained use of health care by members, MSAs were seen by members as a desirable development due to declining benefit packages. Medical schemes have over time moved towards covering the potentially catastrophic costs of hospitalization, with declining coverage of routine health care (such as general practitioner and dental services and acute prescription medicines). Initially, benefit restrictions took the form of increasing co-payments and deductibles but later they took the form of removing such services from the risk-pooled benefit package altogether. This meant that medical scheme members were incurring increasing out-of-pocket payments. By the late 1990s, although medical schemes only covered about 16% of the population, two thirds of all out-of-pocket payments for health care were attributable to medical scheme members (Cornell et al., Reference Cornell2001).

Within this context, many medical scheme members were persuaded, through intensive marketing by the schemes advocating MSAs and by brokers, that MSAs were necessary for financial protection. Anecdotal evidence suggests that there seems to be very little awareness among medical scheme members that “you get only what you pay for” in MSAs and that in fact they were simply spending their own money. Members may be better off placing the money that they contribute to MSAs in a savings account in a financial institution where they can earn interest on these funds (given that few medical schemes offer interest on MSA balances). They would not only benefit from earning interest on these funds, but would also avoid having to go through the inconvenience and cost of paying a provider up front (given that many providers will not directly claim from MSAs), submitting the account to the scheme and sometimes waiting a considerable time for reimbursement. The only benefit to members of an MSA is that it is a form of enforced savings, when many individuals may not be sufficiently disciplined to establish a personal account and routinely deposit savings for health care costs not covered by their scheme, and that they may have access to the value of a full year of savings at any point in the year.Footnote 13

What is of concern is that the introduction of MSAs appears to have contributed to a vicious cycle. Declining benefit packages created a perceived need among members for MSAs, but, in turn, the existence of MSAs has allowed schemes to reduce risk-pooled benefit packages even further. A study by the Council for Medical Schemes (2007), showed that while risk pool contributions and claims had increased by 43.9% and 39.9%, respectively, since 1997 in real terms, MSA contributions and claims increased by 185.6% and 250% respectively in this period.

Equity in financing

Although there is no comprehensive empirical evidence for this at present, it is likely that MSAs do not promote equity in health care financing. This is based on the fact that those who are younger are more likely to choose a benefit option that has an MSA for day-to-day expenses rather than have these expenses covered through a risk pool. This is confirmed by the earlier finding that non-MSA options have an older age profile among schemes that offer both MSA and non-MSA options. This means that contributions to MSAs will be influenced by the member’s perceived risk of requiring health services rather than being income-related. Hence, it is unlikely that contributions to MSAs are such that higher-income members contribute more than lower-income members and MSAs therefore represent a regressive financing mechanism within the insured population. Nevertheless, as it is only higher-income people who are covered by medical schemes, medical scheme contributions (including those with MSAs) are progressive in terms of overall health care financing, that is, the burden of contributing to MSAs does not fall on the poorest households.

Equity in service provision and use

As noted in Chapter 12, although there are no substantial inequities in service provision affecting medical scheme members, there are service provision inequities that favour medical scheme members relative to those not covered by medical schemes. In relation to the use of health services, MSAs undoubtedly contribute to inequities in service use, if defined as the use of health services being distributed according to the need for care. Although the review of risk differentials between MSA and non-MSA members found that there was no significant difference in the incidence of chronic illnesses between the two groups, it did find that MSA options had a membership base with a younger age profile. As most of the common chronic conditions are covered under the risk-pooled PMBs, and as MSAs are primarily used for services such as acute prescription medicines (33% of MSA expenditure in Table 13.1), general practice services (15%), dental care (11%) and allied health professionals (17%), there will be relatively less need for such services among young adults. Older medical scheme members tend to choose benefit options that cover these day-to-day expenses from a risk pool, but the only contributors to this risk pool are members who tend to be equally old and/or with equally high health care needs. By definition, MSAs do not allow risk cross-subsidies, except for within an individual family.

Quality of care and efficiency in the delivery and use of services

While the introduction of MSAs was explicitly viewed as a mechanism for promoting efficiency in health service use, by encouraging individual members to take more responsibility for managing their own health service use and expenses, there is no evidence that MSAs have in fact promoted efficient use of health care. If the introduction of MSAs had promoted efficiency in use, one could reasonably expect that there would have been some slowing down in the rate of annual contribution increases, which has not occurred.

While many factors have contributed to this rapid scheme contribution and expenditure spiral, the lack of improvement in affordability, together with the widespread availability of MSA plans by 2005, casts doubt on the claim by Reference GoreGore (1993) that MSAs are “the only cost containment system that has ever worked.” The temporary reversal of the real cost spiral (in 2005 and 2006) is ascribed to the introduction of the GEMS in January 2006, which is able to achieve cost containment through active purchasing for a very large risk pool,Footnote 14 and through a growing number of medical scheme members buying down to lower-cost scheme options due to the increasing unaffordability of medical scheme cover.

A key issue is that members of medical schemes appear to make little distinction between their risk-pooled and MSA benefits; anecdotal evidence implies that an attitude of wishing to benefit from any contributions made, which is central to moral hazard, appears to prevail. Another issue that militates against MSAs achieving efficiency gains is that there is very limited purchasing power in the MSA context. Each individual is the purchaser of services, and while a health insurance organization could negotiate rates with providers for benefits covered under a risk pool, it has little incentive to do so for services covered under the MSAs, not least of all because members can use their MSAs for a very wide range of service providers.

The one area that has seen a slowdown in real expenditure, and in fact real decreases in expenditure for some years, is that of medicines. Medicine pricing regulations introduced in 2004 have been particularly important in contributing to real decreases in pharmaceutical spending, but increased generic substitution has also been critical in constraining spending on medicines.Footnote 15 The legislative requirement for retail pharmacists to offer individual patients a less expensive generic equivalent to the prescribed medicine is likely to have contributed to efficiency gains in the case of medicines paid for from MSAs. However, much of the efficiency gains from the generic substitution relate to the use of formularies for the treatment of chronic conditions covered by the PMBs.

In terms of quality of care, MSAs could contribute at least to improvements in perceived quality of care. Before MSAs were introduced, the benefit packages covered by medical schemes were relatively restrictive in that they did not cover many providers. Hence, the fact that MSAs can be used to cover the costs of a very wide range of health services (for example, chiropractors, homeopaths and many nonbiomedical healers) has allowed members to consult practitioners of their choice.

Likely impact of proposed mandatory health insurance on MSAs

As indicated in Chapter 12, introduction of some form of mandatory health insurance is planned. This is likely to significantly impact on the MSAs because their major role is to cover day-to-day expenses and the benefit package under a mandatory health insurance is anticipated to cover at least some primary care services. This would weaken the rationale for MSAs. Further, the key goal of the proposed mandatory health insurance is to promote social solidarity through improved income and risk cross-subsidies in the overall health system. As MSAs would not contribute to achieving this goal, they are unlikely to be permitted in the mandatory insurance regulatory context, and possibly even within the top-up insurance (covering treatments not available in the minimum package) environment.

Conclusion

The development of MSAs in South Africa was closely linked with the increasing involvement of insurance companies in health care funding in the late 1980s, which translated into a move away from risk pooling and towards the individualization of risk. Insurers introducing MSAs argued that this development was necessary to promote cost containment through making individuals the main buyers of health care. At the time, medical schemes were faced with rapid cost escalation.

The MSAs have been a successful strategy for highly competitive open medical schemes to grow their businesses. Discovery Health grew from a start-up in early 1993 to being the largest medical scheme, with 2 692 million beneficiaries by December 2015, equivalent to nearly one third of the total number of beneficiaries in private health insurance. Schemes with MSAs have also been somewhat successful in the voluntary environment in keeping some of the younger members in the system, as can be seen from their age profiles submitted to the Risk Equalization Fund.

MSAs have brought some benefits for individuals in the sense that they were introduced at a time when benefit packages were being reduced and co-payments increased. Funds in MSAs could be used to cover the increasing burden of these out-of-pocket payments. In addition, MSA contributions are paid from pre-tax incomes whereas direct out-of-pocket payments are paid from after-tax disposable income. However, a vicious cycle has developed with schemes using the existence of MSAs as a means to further reduce day-to-day benefits and/or increase co-payments on services outside the PMBs package. MSAs have not increased financial protection in reality, as individuals can only benefit to the extent that they contribute, except in the case of scheme members who would otherwise not have saved funds independently to cover unexpected out-of-pocket payments.

In addition, MSAs have the effect of shifting some of the rationing decisions from health care funders to individuals and their families. This has meant that funders avoid the more difficult work of negotiating cost-effective and quality delivery of care with health care providers but can instead concentrate on benefit design and cream-skimming. MSAs have not had the desired effect of dampening moral hazard; in the South African context, there is an urgent need to actively engage in supply-side controls to address spiralling costs rather than continue to further shift the cost and rationing burden to individuals.

Chapter 12 outlined in considerable detail how private health insurance has had a profoundly negative impact on the overall health system in South Africa, particularly in relation to:

its contribution to rapidly spiralling health care expenditure;

its contribution to growing disparities in the public–private mix and undermining the public sector through diverting health professionals away from the public health sector, which serves the vast majority of South Africans; and severely limiting the potential for income and risk cross-subsidies in the overall health system.

Because they are personalized for the individual members and their dependants, MSAs undermine income and risk cross-subsidies even more than risk-pooled private insurance. On this basis, MSAs can be said to be even more detrimental to the overall South African health system than other components of the private health insurance system, both in terms of allowing funders to avoid their responsibility for strategic purchasing and through undermining risk pooling. While private health care funders raised serious concerns about the 2007 decision by the ruling political party to introduce a system of national health insurance, it is precisely their actions in systematically undermining risk pooling that have created the rationale for the introduction of these reforms. The competition provided by GEMS was a significant factor in reining in the use of MSAs to attract members and the 2017 ruling of the Constitutional Court may accelerate the demise of MSAs in medical schemes.

Postscript

Since this Chapter was drafted, the Competition Commission’s Health Market Inquiry released its final report in late 2019 (http://www.compcom.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Final-Findings-and-recommendations-report-Health-Market-Inquiry.pdf). The findings are in line with the analysis presented in this Chapter. In addition, the National Health Insurance Bill was submitted to parliament in 2019, and is undergoing public comment (https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201908/national-health-insurance-bill-b-11–2019.pdf). The Bill is in line with the policy direction laid out in the White Paper.