Introduction

Psychotic disorders (PD), comprising schizophrenia spectrum and affective psychoses, are among the leading causes of disability (Navarro-Mateu et al., Reference Navarro-Mateu, Alonso, Lim, Saha, Aguilar-Gaxiola and Al-Hamzawi2017) and a public health concern worldwide (Anderson, Reference Anderson2019). Impairments of both social functioning (i.e. the ability to fulfil expected roles at work, social activities, and social relations with partners and family) (Long, Stansfeld, Davies, Crellin, & Moncrieff, Reference Long, Stansfeld, Davies, Crellin and Moncrieff2022) and social cognition (i.e. the ability to decode the intentions and behaviours of others) (Green, Reference Green2016) are core features of PD and are thought to underlie severe functional disabilities (de Winter et al., Reference de Winter, Couwenbergh, van Weeghel, Hasson-Ohayon, Vermeulen, Mulder and Veling2021; Vita et al., Reference Vita, Gaebel, Mucci, Sachs, Erfurth, Barlati and Galderisi2022). About two-thirds of individuals with PD are unable to fulfil basic social roles as spouse, parent, or worker. Possibly related to a lack of early interventions (Birchwood, McGorry, & Jackson, Reference Birchwood, McGorry and Jackson1997; McGorry, Reference McGorry2015), these social problems can remain remarkably stable in the years after the first episode of psychosis (FEP) (Velthorst et al., Reference Velthorst, Fett, Reichenberg, Perlman, van Os, Bromet and Kotov2017), also when psychotic symptoms are in remission (Bellack et al., Reference Bellack, Green, Cook, Fenton, Harvey, Heaton and Wykes2007). Accordingly, identifying factors that potentially hinder social functions is a major aim in recovery-oriented treatment and research (Albert, Uddin, & Nordentoft, Reference Albert, Uddin and Nordentoft2018; Javed & Charles, Reference Javed and Charles2018; Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Inagawa, Sueyoshi, Sugawara, Ueda, Omachi and Sumiyoshi2019).

Childhood maltreatment (CM), i.e. physical, emotional or sexual abuse, as well as physical and/or emotional neglect, including witnessing domestic violence and bullying occurring before age 18 years (Teicher & Samson, Reference Teicher and Samson2013), is one of the most serious environmental risk factors for the development of physical or mental illness (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson2009; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton and Dunne2017), including PD (Morgan & Fisher, Reference Morgan and Fisher2007; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer and Bentall2012). Prevalence can vary across populations, but some reports show rates as high as 85% in schizophrenia spectrum disorders and 77% in affective psychoses (Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Andreassen, Aas, Røssberg, Mork, Steen and Lorentzen2013). At least one subtype of CM is reported by around half of individuals with FEP (Vila-Badia et al., Reference Vila-Badia, Del Cacho, Butjosa, Serra Arumí, Esteban Santjusto, Abella and Usall2022), and schizophrenia (Morgan & Fisher, Reference Morgan and Fisher2007).

CM is thought to play a key role in the aetiology and course of PD (Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer and Bentall2012). CM is further related to neurobiological and clinical characteristics (McCrory, De Brito, & Viding, Reference McCrory, De Brito and Viding2011; Teicher & Samson, Reference Teicher and Samson2013) that may lead to difficulties of individuals with PD to engage with and navigate the social world (McCrory, Foulkes, & Viding, Reference McCrory, Foulkes and Viding2022). At a neurobiological level, the diathesis-stress or vulnerability-stress model (Read, Fosse, Moskowitz, & Perry, Reference Read, Fosse, Moskowitz and Perry2014; van Winkel, Stefanis, & Myin-Germeys, Reference van Winkel, Stefanis and Myin-Germeys2008; Vargas, Conley, & Mittal, Reference Vargas, Conley and Mittal2020) posits that experiencing highly stressful or traumatic events, such as CM, may impact on later expression of PD by increasing stress sensitivity to later adversity (Lardinois, Lataster, Mengelers, Van Os, & Myin-Germeys, Reference Lardinois, Lataster, Mengelers, Van Os and Myin-Germeys2011; Lataster, Myin-Germeys, Lieb, Wittchen, & van Os, Reference Lataster, Myin-Germeys, Lieb, Wittchen and van Os2012). It may further have long-lasting effects on the neurobiological processes required to manage the multifaceted roles that are undertaken as part of daily functioning. CM constitutes a stressor that can occur at sensitive periods of development (Schaefer, Cheng, & Dunn, Reference Schaefer, Cheng and Dunn2022), affecting the regular functioning of brain areas involved in the response to stress (e.g. the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis) (Teicher, Samson, Anderson, & Ohashi, Reference Teicher, Samson, Anderson and Ohashi2016). These brain alterations may lead to impaired emotion regulation skills and maladaptive coping strategies (Lincoln, Marin, & Jaya, Reference Lincoln, Marin and Jaya2017), which in turn can lead to poor social functioning in those with PD, as manifested in various areas of their daily life such as occupational functioning (Hjelseng et al., Reference Hjelseng, Vaskinn, Ueland, Lunding, Reponen, Steen and Aas2020; Stain et al., Reference Stain, Brønnick, Hegelstad, Joa, Johannessen, Langeveld and Larsen2014) and interpersonal relations (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Aas, Vorontsova, Trotta, Gadelrab, Rooprai and Alameda2021), including a reduction in the quality and quantity of relationships (McCrory, Ogle, Gerin, & Viding, Reference McCrory, Ogle, Gerin and Viding2019; McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, Foulkes and Viding2022). Neurobiological alterations might also contribute to social cognition difficulties (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Dazzan, Mondelli, Melle, Murray and Pariante2014; Rokita, Dauvermann, & Donohoe, Reference Rokita, Dauvermann and Donohoe2018). For instance, CM has been associated with altered (facial) emotion recognition and processing (Pfaltz et al., Reference Pfaltz, Passardi, Auschra, Fares-Otero, Schnyder and Peyk2019; Rokita et al., Reference Rokita, Holleran, Dauvermann, Mothersill, Holland, Costello and Donohoe2020) and poorer or altered understanding of people's beliefs (theory of mind) (Dorn et al., Reference Dorn, Struck, Bitsch, Falkenberg, Kircher, Rief and Mehl2021; Pang et al., Reference Pang, Zhao, Li, Li, Yu, Zhang and Wang2022), all of which might contribute to diminished social involvement in those with PD.

Moreover, a heightened emotional reactivity to daily stressors seems robustly related to the severity of psychotic experiences and negative affect (Paetzold et al., Reference Paetzold, Myin-Germeys, Schick, Nelson, Velthorst, Schirmbeck and Reininghaus2021; Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Kempton, Valmaggia, Craig, Garety, Onyejiaka and Morgan2016; van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, Lecei, Myin-Germeys, Collip, Viechtbauer, Jacobs and van Winkel2018). CM relates to depressive symptoms and suicide attempts, and the occurrence, severity and persistence of both hallucinations and delusions, as well as negative symptoms (Alameda et al., Reference Alameda, Christy, Rodriguez, Salazar de Pablo, Thrush, Shen and Murray2021). All these domains of symptoms might be related to diminished social involvement in individuals with PD during early (Stain et al., Reference Stain, Brønnick, Hegelstad, Joa, Johannessen, Langeveld and Larsen2014) and active illness phases, as well as during remission (Hjelseng et al., Reference Hjelseng, Vaskinn, Ueland, Lunding, Reponen, Steen and Aas2020; Pruessner et al., Reference Pruessner, King, Veru, Schalinski, Vracotas, Abadi and Joober2021). In fact, differential effects of CM on clinical outcome may not be apparent at PD onset, but only become evident through poor symptomatic remission and global social functioning over time (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Andreassen, Aminoff, Færden, Romm, Nesvåg and Melle2016; Pruessner et al., Reference Pruessner, King, Veru, Schalinski, Vracotas, Abadi and Joober2021).

Despite the well-established link between CM and PD (Schäfer & Fisher, Reference Schäfer and Fisher2011; Stanton, Denietolis, Goodwin, & Dvir, Reference Stanton, Denietolis, Goodwin and Dvir2020) across specific subtypes of CM (Ajnakina et al., Reference Ajnakina, Trotta, Forti, Stilo, Kolliakou, Gardner-Sood and Fisher2018) and symptoms dimensions (Alameda et al., Reference Alameda, Christy, Rodriguez, Salazar de Pablo, Thrush, Shen and Murray2021), and increasing recognition that social functions are closely related to adverse experiences in childhood in adults with PD (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Harvey, Hayes, Castle, Galletly, Sweeney and Spittal2020), meta-analytic research assessing the magnitude and consistency of associations between different subtypes of CM and domains of social functioning and social cognition in PD is lacking. Lately, the research about PD and CM has generated wide interest in researchers. One prior meta-analysis has quantitatively examined associations between broadly defined and specific types of childhood adversities and functional outcomes in PD. This study found small negative associations of CM with global social functioning and no association with occupational functioning. This study, however, focused on global aspects of functional outcomes, as well as on the social and occupational domains independently (Christy et al., Reference Christy, Cavero, Navajeeva, Murray-O'Shea, Rodriguez, Aas and Alameda2022). Furthermore, the nature of the association between overall, broadly defined CM, and specific subtypes, across global and specific domains of social functioning and social cognition has not been appraised. Examination of whether there are differences between diagnoses (non-affective v. affective psychoses) in how CM relates to social outcomes in different illness stages (FEP v. chronic PD) (Breitborde, Srihari, & Woods, Reference Breitborde, Srihari and Woods2009) is also warranted, given fundamental differences in how these disorders present (Chen, Liu, Liu, Zhang, & Wu, Reference Chen, Liu, Liu, Zhang and Wu2021; de Winter et al., Reference de Winter, Couwenbergh, van Weeghel, Hasson-Ohayon, Vermeulen, Mulder and Veling2021; Torrent et al., Reference Torrent, Reinares, Martinez-Arán, Cabrera, Amoretti, Corripio and group2018).

Moreover, some factors are thought to moderate between CM and social outcomes (e.g. age at the time of exposure) (Alameda et al., Reference Alameda, Ferrari, Baumann, Gholam-Rezaee, Do and Conus2015, Reference Alameda, Golay, Baumann, Ferrari, Do and Conus2016) in PD. In addition, knowledge on possible mediators (depressive symptoms) (Alameda et al., Reference Alameda, Rodriguez, Carr, Aas, Trotta, Marino and Murray2020) of proposed association between CM and both impairments in social functioning and social cognition could help to understand underlying mechanisms to design interventions that might be more effective for those with PD and CM. To date the possible mediators and moderators in the association between CM and social functioning and social cognition in PD have never been reviewed and synthesised. The respective synthesis would improve our understanding of whether CM relates to social functioning and social cognition and might provide targets to develop preventive strategies and effective interventions to improve social outcomes in people with PD and CM histories.

Therefore, the first aim of our systematic review and meta-analysis was to provide an estimate on the magnitude and consistency of associations between CM (overall and its subtypes) and global and different domains of social functioning and social cognition in adults with PD. The second aim was to examine and narratively summarise moderators and mediators of these associations. We hypothesised that CM would be related to poorer social functioning and social cognition in individuals with PD.

Methods

This Study protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020175244) and published elsewhere before completion of the study (Fares-Otero, Pfaltz, Rodriguez-Jimenez, Schäfer, & Trautmann, Reference Fares-Otero, Pfaltz, Rodriguez-Jimenez, Schäfer and Trautmann2021). This review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guideline (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow and Moher2021) (see ST1 and ST2 in the supplement), the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) (Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie and Thacker2000) (see ST3 in the supplement), and the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) (Altman, Simera, Hoey, Moher, & Schulz, Reference Altman, Simera, Hoey, Moher and Schulz2008) reporting guidelines. For a comprehensive glossary of terms used in this work, see SA1 in the supplement.

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic literature search using multiple Medical Subject Headings and keywords related to: (1) ‘psychosis’; (2) ‘childhood maltreatment’; (3) ‘social functioning’ OR ‘social cognition’ using the Boolean operator ‘AND’ (see the search strategy and terms appended in SA2 in the supplement) was conducted in PubMed (Medline), PsycINFO, Embase, Web of Science (Core Collection), and PILOTS, initially searched for inception from 1990 until 25 June 2021, and updated twice, on 4 March 2022, and on 24 November 2022. The following filters were used: human samples, written in English, German, and Spanish, and removal of duplicates. To identify additional eligible articles, the reference lists of the included articles and relevant studies already included in the previously identified meta-analysis (Christy et al., Reference Christy, Cavero, Navajeeva, Murray-O'Shea, Rodriguez, Aas and Alameda2022) were cross referenced manually.

Titles and abstracts of articles were independently screened by three reviewers (NEF-O, L-MN, SW) (89.15% agreement); discrepancies were resolved through discussion with an independent reviewer (ST). After excluding irrelevant articles, full-texts were independently assessed for eligibility by three reviewers (NEF-O, L-MN, SW) (88.90% agreement); full-text discrepancies were screened by an independent reviewer (ST) and resolved through consensus. The software Zotero was used to manage citations and remove duplicates. The software Rayyan QCRI (https://rayyan.qcri.org/) was used to manage citations, remove duplicates, and screening in the search updates. Because of high agreement during first screening, NEF-O independently conducted the search updates; discrepancies were resolved through discussion with an independent reviewer (ST).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

According to the PICO framework, studies were included if they: (1) (P) were conducted in individuals with PD spectrum, including non-affective PD (schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder) and affective PD (bipolar disorder, major depression with psychotic features) based on ICD (World Health Organization, 1993) and DSM (DSM-5 Diagnostic Classification, 2013) criteria (see manual codes of PD diagnoses in ST4 in the supplement); (2) (I) assessed the presence of CM defined as physical/emotional/sexual abuse and/or physical/emotional neglect, including domestic violence and bullying, occurring before age 18 (Teicher & Samson, Reference Teicher and Samson2013) and measured as overall (total) or specific CM subtypes (3) (C) compared individuals with and without CM within the same sample population of individuals with PD; (4) (O) evaluated social functioning or social cognition with validated instruments (see details in section 2.3); (5) quantitatively examined and reported associations between CM (exposure variable) and social functioning or social cognition (outcome variable) or data that allowed correlations to be calculated, or provided these data on request (see the definition and operationalisation of exposure and outcome variables in SA3 in the supplement); (6) were original research articles published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) were reviews, clinical case studies, abstracts, conference proceedings, study protocols, letters to the editor not reporting original data, theoretical pieces, or grey literature; (2) only recruited children or adolescents; (3) only investigated animals; (4) involved interventions and/or assessed treatment outcomes not providing baseline data.

Study outcomes

After study selection, we categorised the study outcomes into six separate domains of social functioning and four separate domains of social cognition. The selection of outcome domains was based on outcomes examined in the included studies, and categorisations used in previous meta-analyses in the field (Christy et al., Reference Christy, Cavero, Navajeeva, Murray-O'Shea, Rodriguez, Aas and Alameda2022; de Winter et al., Reference de Winter, Couwenbergh, van Weeghel, Hasson-Ohayon, Vermeulen, Mulder and Veling2021; Fares-Otero et al., Reference Fares-Otero, De Prisco, Oliva, Radua, Halligan, Vieta and Martinez-Aran2023).

Social functioning

(1) Global social functioning: overall functioning in a social setting or role in any social domain (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Andreassen, Aminoff, Færden, Romm, Nesvåg and Melle2016; de Winter et al., Reference de Winter, Couwenbergh, van Weeghel, Hasson-Ohayon, Vermeulen, Mulder and Veling2021); (2) Independent living: independent functioning (Monfort-Escrig & Pena-Garijo, Reference Monfort-Escrig and Pena-Garijo2021), autonomy, and financial management (Shah et al., Reference Shah, Mackinnon, Galletly, Carr, McGrath, Stain and Morgan2014); (3) Occupational functioning: vocational functioning, involvement into (competitive) employment/work (Lindgren et al., Reference Lindgren, Mäntylä, Rikandi, Torniainen-Holm, Morales-Muñoz, Kieseppä and Suvisaari2017); (4) Interpersonal relations: social relationships and community functioning; (5) Aggressive behaviour: social violent behaviour, including hostility and criminality (Bosqui et al., Reference Bosqui, Shannon, Tiernan, Beattie, Ferguson and Mulholland2014); and (6) Psychosocial problems: Axis IV psychosocial and environmental problems (Ramsay, Flanagan, Gantt, Broussard, & Compton, Reference Ramsay, Flanagan, Gantt, Broussard and Compton2011).

Social cognition

(1) Theory of mind: ability to reason about mental states and understand intentions, dispositions, emotions, and beliefs of both oneself and others or mentalising (Brüne, Reference Brüne2005; Kincaid et al., Reference Kincaid, Shannon, Boyd, Hanna, McNeill, Anderson and Mulholland2018); (2) Emotion processing: ability to manage emotions, and to identify, recognise, understand (facial) emotions of others (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Kauppi, Brandt, Tesli, Kaufmann, Steen and Melle2017); (3) Attributional style/bias: the way in which individuals infer the causes of particular social events (Chalker et al., Reference Chalker, Parrish, Cano, Kelsven, Moore, Granholm and Depp2022; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019); and (4) Empathy: ability to comprehend and share the emotions of others (Bonfils, Lysaker, Minor, & Salyers, Reference Bonfils, Lysaker, Minor and Salyers2017).

Appendix SA3 in the supplement provides a complete definition and operationalisation of each outcome domain, and ST5 provides a complete overview of assessments of each outcome domain.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data from eligible studies were extracted and tracked in Microsoft Excel by three independent reviewers (NEF-O, L-MN, SW) using a structured coding form; discrepancies were resolved through consensus with an additional reviewer (ST) to ensure high quality of data extraction.

Descriptive variables extracted included first author and publication year, country/region, sample size, mean age (with standard deviation), percentage of males in the sample, study design, type of diagnosis in the sample, type and instrument for diagnosis (and criteria), duration (in years) of the illness, CM instrument used and type of CM exposure reported (overall CM and/or subtypes), social functioning or social cognition instrument/measure, results on the association between CM and social functioning or social cognition (including p value, effect size and descriptive summary), confounders, moderators, and mediators investigated in the included studies (if reported).

Correlation coefficients (r) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extracted as measures of effect size. If not reported, information was transformed from available statistics (e.g. mean and standard deviations between groups comparisons, unstandardised regression coefficients, and standardised β coefficients, and odds ratios), as per procedures used in previous meta-analyses (Alameda et al., Reference Alameda, Christy, Rodriguez, Salazar de Pablo, Thrush, Shen and Murray2021; Christy et al., Reference Christy, Cavero, Navajeeva, Murray-O'Shea, Rodriguez, Aas and Alameda2022; Fares-Otero et al., Reference Fares-Otero, De Prisco, Oliva, Radua, Halligan, Vieta and Martinez-Aran2023), using established formulas (Practical Meta-Analysis, 2022). Corresponding authors were contacted by email to retrieve additional information if necessary. Studies that reported either an overall (total) continuous score of CM, or binary category (high/low exposure), and/or a score for the CM subtypes (subscales) were included into one or more of the meta-analyses conducted. In the case where no overall CM effect was reported, only the effects of specific subtypes of CM were extracted to be included in meta-analyses. For longitudinal studies, data indicating associations at baseline were extracted (see a detailed description of the extracted variables in SA4 in the supplement).

The quality and risk of bias assessment was independently assessed by two independent reviewers (NEF-O, ST) using an adapted version of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) (Wells et al., Reference Wells, Wells, Shea, Shea, O'Connell, Peterson and Petersen2014) for non-randomised (cross-sectional and longitudinal) studies which contains additional items to assess sample size, confounders, and statistical tests, recommended by Cochrane Handbook (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Gøtzsche, Jüni, Moher, Oxman and Sterne2011) (see SA5, ST5 and ST6 in the supplement).

Statistical analysis

All quantitative analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis v4.0 (CMA, version 4 -meta-analysis.com) (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein, Egger, Higgins and Smith2022a). A PRISMA-compliant systematic review (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow and Moher2021) and random-effect meta-analyses (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2011) were conducted applying the DerSimonian-Laird estimator (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2022), when a minimum of five studies were available (Jackson & Turner, Reference Jackson and Turner2017). If the number of available effect sizes did not allow random effects meta-analysis, study findings were summarised and appraised qualitatively.

We conducted separate meta-analyses with random-effect estimates to quantify associations between each CM subtype or overall CM and social functioning (global, independent living, occupational functioning, interpersonal relations, aggressive behaviour) or social cognition (theory of mind and emotion processing) domain. For studies conducting separate analyses for men and women (Penney, Pruessner, Malla, Joober, & Lepage, Reference Penney, Pruessner, Malla, Joober and Lepage2022), physical and verbal aggression (Spidel, Lecomte, Greaves, Sahlstrom, & Yuille, Reference Spidel, Lecomte, Greaves, Sahlstrom and Yuille2010), independence competence and performance (Monfort-Escrig & Pena-Garijo, Reference Monfort-Escrig and Pena-Garijo2021), and disorganised attachment styles (Aydin et al., Reference Aydin, Balikci, Tas, Aydin, Danaci, Bruene and Lysaker2016; Hodann-Caudevilla, García, & Julián, Reference Hodann-Caudevilla, García and Julián2021), results were pooled using correction estimates (Olkin & Pratt, Reference Olkin and Pratt1958) before inclusion to meta-analyses.

For those studies not reporting correlation coefficients, the ‘Practical Meta-Analysis Effect Size Calculator’ (Practical Meta-Analysis, 2022) was used to convert the reported statistics. Pearson correlation coefficients (effect sizes) were Fisher's Z transformed and back transformed after pooling. Thus, all pooled effects are reported as correlation coefficients. A small number of effects (1.9%) were reported as null findings without sufficient information to calculate effect sizes. These effects were not excluded to avoid upward bias of effect estimation. Instead, they were set to zero, resulting in rather conservative pooled effect size estimations (Albajes-Eizagirre, Solanes, & Radua, Reference Albajes-Eizagirre, Solanes and Radua2019).

Analyses for heterogeneity were performed using Cochran's Q-test and I 2 statistics with significant heterogeneity being indicated by I 2 ⩾ 50% (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003) [25, 50, and 75% defining thresholds for low, moderate, and high heterogeneity (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2022)]. Alongside the 95% CI and the mean pooled effect provided, the prediction intervals, to estimate to which extent effect sizes vary across studies (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein2022b), were displayed as part of the forest plots (marked in red).

The forest plots were explored, and one-study-removed sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether a particular study or a set of studies were contributing to the potential heterogeneity (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein, Egger, Higgins and Smith2022a).

To further examine potential factors explaining heterogeneity, a series of random-effect meta-regressions (López-López, Van den Noortgate, Tanner-Smith, Wilson, & Lipsey, Reference López-López, Van den Noortgate, Tanner-Smith, Wilson and Lipsey2017) were conducted on pre-selected variables: mean sample age, percentage of male individuals, non-affective v. affective psychosis samples, FEP (illness duration <2 years) v. chronic PD samples, diagnostic instrument (structured interview v. clinical judgment), use of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) v. any other instrument to assess CM, use of self-report v. clinician judgment to assess social functioning, use of behavioural data v. any other instrument to assess social cognition, and study quality (NOS rating) as per procedures used in previous meta-analyses (Christy et al., Reference Christy, Cavero, Navajeeva, Murray-O'Shea, Rodriguez, Aas and Alameda2022; de Winter et al., Reference de Winter, Couwenbergh, van Weeghel, Hasson-Ohayon, Vermeulen, Mulder and Veling2021; Fares-Otero et al., Reference Fares-Otero, De Prisco, Oliva, Radua, Halligan, Vieta and Martinez-Aran2023). Because of the limited number of included studies in some analyses (n < 10) (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein, Egger, Higgins and Smith2022a; Higgins & Thompson, Reference Higgins and Thompson2004), meta-regression analyses should be considered exploratory. Other evidence of confounders (section 3.2., Table 1) and effect moderators and mediators examined in the included studies (section 3.7. Fig. 3) on associations between CM and social outcomes was narratively synthesised (Popay et al., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers and Duffy2006).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of included studies

AoM, Awareness of the Mind of the Other; BBTS, The Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey; BD, Bipolar Disorder; BDHI, Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory; BES, The Basic Empathy Scale; BLERT, Bell Lysaker Emotional Recognition Task; CAMIR-R, from French; Cartes-Modeles Individuels de Relations (Short form); CAQ, Childhood Abuse Questionnaire; CASH, The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History; CECA-Q, Childhood Experiences of Care and Abuse Questionnaire; CEVQ, Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire; CSTQ, Childhood Sexual Trauma Questionnaire; CT, Childhood Trauma; CTQ (-SF), Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (-Short Form); DFAR, The degraded facial affect recognition task; DIP, Diagnostic Interview for Psychosis; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DV, Domestic Violence; EA, Emotional Abuse; ECR-R, Experience in Close Relationships Revised; EN, Emotional Neglect; ERT, Emotion Recognition Task; ETISR-SF, The Early Trauma Inventory Self Report-Short Form; ExpTra-S, Screening of Early Traumatic Experiences in Patients with Severe Mental Illness; FAST, Functioning Assessment Short Test; FEEST, Facial Expressions of Emotion Stimuli and Tests; FEP, First Episode Psychosis; GAF (-F), Global Assessment of functioning (Function subscale); GAS, Global Assessment Scale; HCR-20, The Historical Clinical Risk Management-20; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision; INQ, Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire; IPII, The Indiana Psychiatric Illness Interview; ISMI, Internalised Stigma – Social Withdrawal; IQ, Intelligence quotient; LHA-A, Lifetime History of Aggression Scale-Aggression Subscale; MACE, Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure Scale; MAS-A, Metacognition Assessment Scale-Abbreviated; MASC, Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition; MCCB, MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery; MDD, Major Depressive Disorder; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MOAS, Modified Overt Aggression Scale; MSCEIT, Mayer Salovery Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; NS, Not specified, OPCRIT, Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness and Affective Illness (v.4.0.: checklist to generate DSM-IV diagnoses for PD); PA, Psychical Abuse; PAM, Psychosis Attachment Measure; PD, Psychotic Disorder; PERE, from Spanish; Prueba de Reconocimiento de Emociones or Emotion recognition Task; PN, Physical Neglect; PSPS, Personal and Social Performance Scale; PsyQol, Psychological Quality of Life; QoL, Quality of Life; QSF, Questionnaire of Social Functioning; RMET, Reading the Mind in the Eyes Task; SA, Sexual Abuse; SASS, Social Adaptation Task-Multiple Choice; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAT-MC, Social Attribution Task-Multiple Choice; SCAN, Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SCID-I, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders – Axis I; SECT, Social Emotional Cognition Task; SFS, Social Functioning Scale; SCZ, Schizophrenia; SF-36; Short Form-36 Health-related QoL-Psychological Subscore; SOFAS, Social and Occupational Functioning; SQoL, Social Quality of Life; TAA, Trauma Assessment for Adults; TASIT, The Awareness of Social Inference Test; TEC, Traumatic Experience Checklist; ToM, Theory of Mind; WHOQOL_BREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life.

To examine publication bias, funnel plots were visually inspected, investigating possible outliers or studies going in the opposite direction of all the others, and the intercept Egger's test was used to numerically explore the risk of publication bias (namely Egger's test p value <0.05) (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Gøtzsche, Jüni, Moher, Oxman and Sterne2011; Lin & Chu, Reference Lin and Chu2018). Where indications for publication biases were found, corrected effect sizes using the Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill method were additionally reported to correct for significant publication bias (Duval & Tweedie, Reference Duval and Tweedie2000).

Statistical significance was evaluated two-sided at the 5% threshold (two tailed). Interpretation of correlations coefficients was based on predefined cut-offs as follows: r values between 0 and 0.3 indicate small, values between 0.3 and 0.7 indicate moderate, and values above 0.7 indicate strong associations (Ratner, Reference Ratner2009).

Results

Study inclusion and characteristics

Of 5350 eligible studies, 283 were full text screened, and 53 were included in the qualitative synthesis, of which 51 studies were included in the quantitative synthesis, contributing to 125 effect sizes pooled in meta-analyses (see the process of study selection in detail in Fig. 1, the full list of included studies in SA6, and excluded studies with reasons in SA7 in the supplement).

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flowchart outlining the study selection process.

The total sample of the included studies compromised 13 635 individuals with PD (sample size range 25–1825), of which 9429 (69.2%) were male. The mean age was 33.9 (s.d. = 7.7; range = 22–48) years. Of the 53 included studies, 14 (26.4%) studies included samples with non-affective PD, and 10 (19.2%) studies included samples with FEP.

Sample sizes of the 51 included studies included in the meta-analyses ranged from 25 to 1825, comprising a total of 13 260 individuals with PD, of which 9236 (69.7%) were male. The mean age was 34.02 (s.d. = 7.44; range = 22–48) years. Fourteen (27.5%) of the samples of the 51 included studies fulfilled criteria for non-affective PD, and 9 (18%) studies included samples with FEP.

A structured clinical interview was used in 32 (60.4%) of the included studies for the assessment of PD. The SCID-Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (First & Gibbon, Reference First and Gibbon2004) was the most frequently used diagnostic instrument. It was used in 17 (32.7%) studies, followed by the OPCRIT electronic system (Rucker et al., Reference Rucker, Newman, Gray, Gunasinghe, Broadbent, Brittain and McGuffin2011) in 5 (9.4%) studies. Ten (18.9%) studies used an unstructured clinical interview based on DSM, while five (9.4%) studies used ICD criteria, and six (11.3%) studies used a clinical judgment (non-specified criteria).

Fifty (94.3%) of the 53 included studies were cross-sectional. The CTQ, including shortened (Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge, Ahluvalia and Zule2003) or translated versions, was the most used instrument to measure CM in 31 (58.5%) studies, and the Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire (CECA.Q) (Bifulco, Bernazzani, Moran, & Jacobs, Reference Bifulco, Bernazzani, Moran and Jacobs2005) was used in three (5.7%) studies. Four (7.6%) studies reported CM results from a clinical interview.

Overall CM was the most frequently assessed variable, being examined in 34 (62.75%) of the included studies, while 28 (52.8%) studies examined only CM subtypes, and eight (15.1%) studies examined both overall CM and all subtypes. Twenty-five (47.2%) studies examined physical abuse, 27 (50.9%) studies examined sexual abuse, 18 (34.0%) studies examined emotional abuse, 18 (34.0%) studies examined emotional neglect, and 17 (32.1%) studies examined physical neglect.

Of note, five studies investigated types of maltreatment that could not be pooled in meta-analysis (n < 5 and/or k < 5) (Jackson & Turner, Reference Jackson and Turner2017) such as aggregated scores for abuse and neglect (Brañas, Lahera, Barrigón, Canal-Rivero, & Ruiz-Veguilla, Reference Brañas, Lahera, Barrigón, Canal-Rivero and Ruiz-Veguilla2022; Kilian et al., Reference Kilian, Asmal, Chiliza, Olivier, Phahladira, Scheffler and Emsley2018; Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019), separation from parents and domestic violence (Oakley, Harris, Fahy, Murphy, & Picchioni, Reference Oakley, Harris, Fahy, Murphy and Picchioni2016), and parental harsh discipline (Ramsay et al., Reference Ramsay, Flanagan, Gantt, Broussard and Compton2011). Among these studies, a negative association between neglect (but not abuse) and emotion processing [r = −0.45 (CI −0.64 to −0.21), p < 0.001] was found in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Kilian et al., Reference Kilian, Asmal, Chiliza, Olivier, Phahladira, Scheffler and Emsley2018). Yet no association between abuse and theory of mind was found in individuals with non-affective PD (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019). While others found no association between abuse and theory of mind or emotion recognition of different emotions except for better recognition of fearful faces (r = 0.32 (CI 0.05–0.54)] in FEP (Brañas et al., Reference Brañas, Lahera, Barrigón, Canal-Rivero and Ruiz-Veguilla2022). A positive association between childhood exposure to domestic violence [r = 0.54 (CI 0.32 to −0.71), p = 0.001] and separation from parents [r = 0.34 (CI 0.08–0.56), p = 0.015] but not child abuse and propensity to violent behaviour was found in adults with schizophrenia (Oakley et al., Reference Oakley, Harris, Fahy, Murphy and Picchioni2016). Finally, a positive association between parental harsh discipline and psychosocial problems was found [r = 0.28 (CI 0.03–0.50)] in people with FEP (Ramsay et al., Reference Ramsay, Flanagan, Gantt, Broussard and Compton2011).

Of the 53 included studies, 34 (70.8%) examined social functioning, of which 21 (61.8%) used self-report questionnaires (v. clinician judgment). Nineteen studies examined social cognition, of which ten (52.6%) used behavioural data (v. any other instrument). Across studies, five social functioning and four social cognition domains were examined, of which four domains of social functioning and two domains of social cognition had sufficient data for meta-analysis.

Of the 51 included studies in the meta-analyses, 33 (62.3%) examined social functioning. Global social functioning was most frequently examined in a total of 21 (39.6%) studies. In terms of social functioning domains, eight (15.1%) studies examined independent living, 13 (24.5%) studies examined occupational functioning, 14 (26.4%) studies examined interpersonal relations, and 11 (20.8%) studies examined aggressive behaviour. No studies examined associations between CM subtypes and independent living or occupational functioning, or interpersonal relations (except for sexual abuse) in PD. No studies examined the association between CM subtypes (except for physical and sexual abuse) and aggressive behaviour. One above-mentioned study concerning a positive association between parental harsh discipline and psychosocial problems in FEP (Ramsay et al., Reference Ramsay, Flanagan, Gantt, Broussard and Compton2011) could not be meta-analysed.

In terms of social cognition domains, a total of 19 (34.0%) studies were examined, of which ten (18.9%) studies examined theory of mind, and 11 (20.8%) examined emotion processing. No studies examined the relationship between CM subtypes and emotion processing or (except for sexual abuse) theory of mind. Two studies concerning associations of CM with empathy (Cui et al., Reference Cui, Kim, Lee, Kim, Yu, Lee and Chung2019; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019), and two studies concerning associations of CM with attributional style/bias (Chalker et al., Reference Chalker, Parrish, Cano, Kelsven, Moore, Granholm and Depp2022; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019) could not be meta-analysed. Among these studies, no association between overall CM and empathy was found in FEP (Cui et al., Reference Cui, Kim, Lee, Kim, Yu, Lee and Chung2019). Although a negative association between emotional neglect and empathy (cognitive trait) [r = −0.47 (95% CI 0.72 to −0.11)] was found in individuals with schizophrenia, no significant correlation was observed after controlling for gender, age, duration of illness, and medication (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019). Furthermore, the same study (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019) found no association between CM and attributional style, while others found that only emotional abuse was associated with more negative and hostile social attributional biases in PD (Chalker et al., Reference Chalker, Parrish, Cano, Kelsven, Moore, Granholm and Depp2022).

Twenty-nine studies controlled for confounders in their analysis, and several adjusted for sex (Brañas et al., Reference Brañas, Lahera, Barrigón, Canal-Rivero and Ruiz-Veguilla2022; Quide et al., Reference Quide, Cohen-Woods, O'Reilly, Carr, Elzinga and Green2018; Sweeney, Air, Zannettino, & Galletly, Reference Sweeney, Air, Zannettino and Galletly2015) or gender (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019; Monfort-Escrig & Pena-Garijo, Reference Monfort-Escrig and Pena-Garijo2021; van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, Bak, de Graaf, Ten Have, van Dorsselaer and van Winkel2016). A wide range of confounders were considered. These included family income and socioeconomic status (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Harvey, Hayes, Castle, Galletly, Sweeney and Spittal2020), residence (city v. rural area), parental styles (Rokita et al., Reference Rokita, Dauvermann, Mothersill, Holleran, Holland, Costello and Donohoe2021), attachment dimensions (Hjelseng et al., Reference Hjelseng, Vaskinn, Ueland, Lunding, Reponen, Steen and Aas2020), and first-degree relative mental illness (Trauelsen et al., Reference Trauelsen, Gumley, Jansen, Pedersen, Nielsen, Haahr and Simonsen2019). Also, child premorbid social, cognitive (Hodann-Caudevilla et al., Reference Hodann-Caudevilla, García and Julián2021), and academic functioning (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Andreassen, Aminoff, Færden, Romm, Nesvåg and Melle2016), IQ (Vaskinn, Melle, Aas, & Berg, Reference Vaskinn, Melle, Aas and Berg2021), educational level (yeas of education) (Schalinski, Teicher, Carolus, & Rockstroh, Reference Schalinski, Teicher, Carolus and Rockstroh2018) as well as gender (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019; Monfort-Escrig & Pena-Garijo, Reference Monfort-Escrig and Pena-Garijo2021; van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, Bak, de Graaf, Ten Have, van Dorsselaer and van Winkel2016), sex (Brañas et al., Reference Brañas, Lahera, Barrigón, Canal-Rivero and Ruiz-Veguilla2022; Quide et al., Reference Quide, Cohen-Woods, O'Reilly, Carr, Elzinga and Green2018; Sweeney et al., Reference Sweeney, Air, Zannettino and Galletly2015), ethnicity (Rosenberg, Lu, Mueser, Jankowski, & Cournos, Reference Rosenberg, Lu, Mueser, Jankowski and Cournos2007), age at psychosis onset (Penney et al., Reference Penney, Pruessner, Malla, Joober and Lepage2022), duration of illness (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019), severity of positive symptoms (Lysaker, Wright, Clements, & Plascak-Hallberg, Reference Lysaker, Wright, Clements and Plascak-Hallberg2002), type of PD diagnosis (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Kauppi, Brandt, Tesli, Kaufmann, Steen and Melle2017), psychopathy, lifetime substance use disorders (Oakley et al., Reference Oakley, Harris, Fahy, Murphy and Picchioni2016), cannabis use (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019) and antipsychotic medication (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019) were considered.

The included studies were published between 2001 and 2022 and were conducted in Europe (n = 30), North America (n = 10), Asia (n = 3), Australia (n = 6), Turkey (n = 2), Brazil (n = 1), and South Africa (n = 1) (see a detailed description of demographic and clinical characteristics of the included studies in Table 1).

Study quality assessment

The mean quality rating (range between 0 and 8) of the included studies was 5.28 (s.d. = 1.09), range 4–8. Overall, 14 (26.4%) studies were rated as ‘poor’ (NOS score = 4), 20 (37.7%) studies were rated as ‘fair’ (NOS score = 5), 11 (20.8%) studies were rated as ‘good’ (NOS score = 6), and 8 (15.1%) studies received a rating considered as ‘high’ (NOS score >6). Of those rated as ‘high’, six (11.3%) studies (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Andreassen, Aminoff, Færden, Romm, Nesvåg and Melle2016; Andrianarisoa et al., Reference Andrianarisoa, Boyer, Godin, Brunel, Bulzacka and Aouizerate2017; Bosqui et al., Reference Bosqui, Shannon, Tiernan, Beattie, Ferguson and Mulholland2014; Li et al., Reference Li, Li, Liu, Zhang, Tang and Wang2015; Rosenberg et al., Reference Rosenberg, Lu, Mueser, Jankowski and Cournos2007; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Harvey, Hayes, Castle, Galletly, Sweeney and Spittal2020) examined social functioning, and two (3.8%) studies (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019; Trauelsen et al., Reference Trauelsen, Gumley, Jansen, Pedersen, Nielsen, Haahr and Simonsen2019) examined social cognition (see further details of the study quality assessment in ST6 and ST7 in the supplement).

The representativeness of samples was mixed, and most of the included studies did not report either on non-response or a priori power analyses or otherwise justified their sample sizes. More than half of the included studies (n = 29) controlled for confounders in their design or analysis, and several adjusted for sex (Brañas et al., Reference Brañas, Lahera, Barrigón, Canal-Rivero and Ruiz-Veguilla2022; Quide et al., Reference Quide, Cohen-Woods, O'Reilly, Carr, Elzinga and Green2018; Sweeney et al., Reference Sweeney, Air, Zannettino and Galletly2015) or gender (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019; Monfort-Escrig & Pena-Garijo, Reference Monfort-Escrig and Pena-Garijo2021; van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, Bak, de Graaf, Ten Have, van Dorsselaer and van Winkel2016) (see section 3.1. and Table 1). Many studies did not fully report results from statistical tests, e.g. omitting named effect estimates, p values, or measures of precision if appropriate (such as standard errors or confidence intervals).

Meta-analyses of associations between childhood maltreatment and social functioning

Overall childhood maltreatment

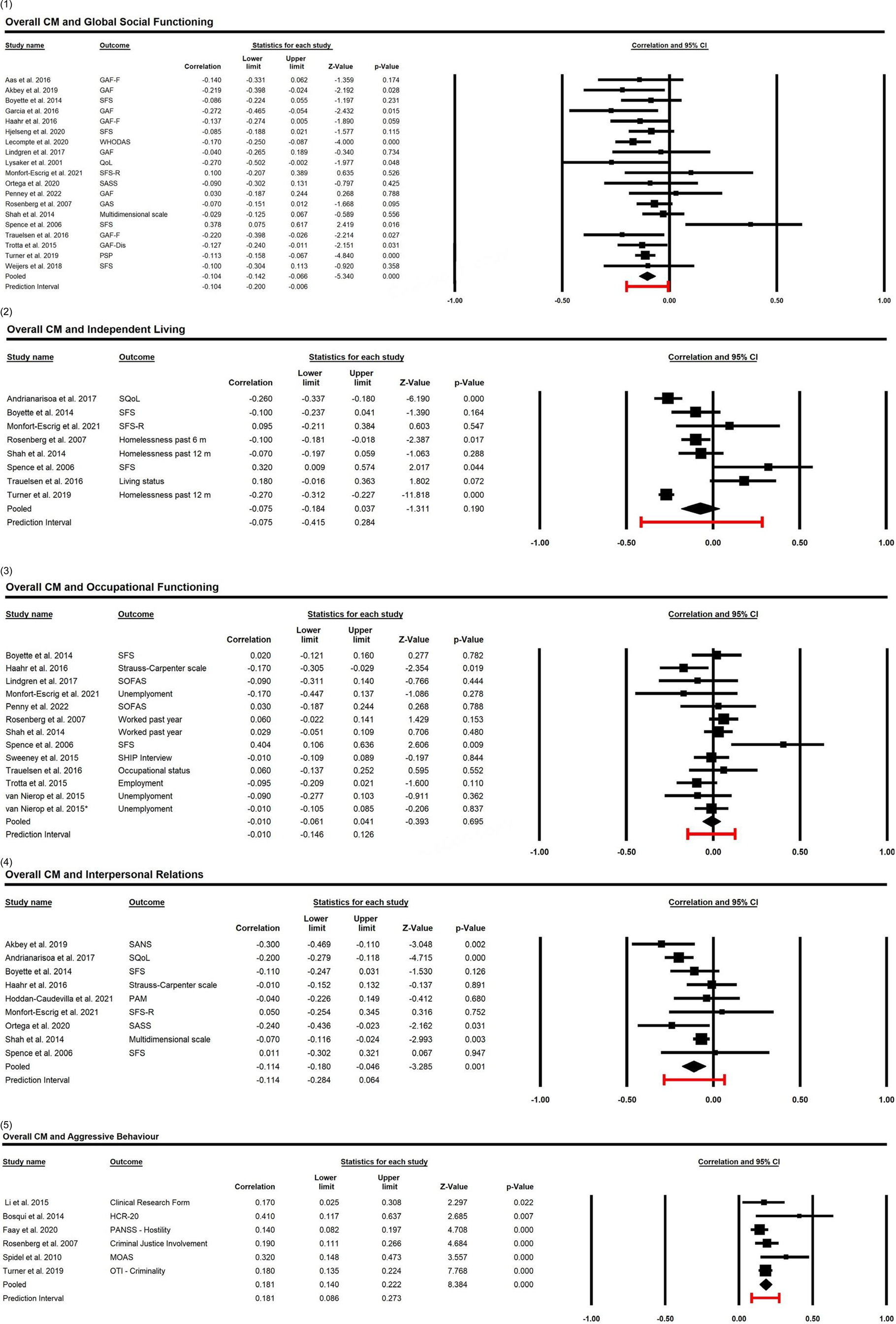

Overall CM was negatively associated with global social functioning [n = 19, k = 19, r = −0.104 (95% CI −0.142 to −0.066), p < 0.001], as well as interpersonal relations [n = 9, k = 9, r = −0.114 (95% CI −0.180 to −0.046), p = 001], and positively associated with aggressive behaviour [n = 6, k = 6, r = 0.181 (CI 0.140–0.222), p < 0.001] (see Table 2 and forest plots in Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Forest plots investigating associations between overall childhood maltreatment and social functioning: (1) Global social functioning, (2) Independent living, (3) Occupational functioning, (4) Interpersonal relations, and (5) Aggressive behaviour in individuals with psychotic disorders.

Table 2. Meta-analyses of associations between childhood maltreatment and social outcomes in individuals with psychotic disorders

Note: *Two effect sizes from two different populations in the same study were meta-analysed.

Childhood maltreatment subtypes

All subtypes of CM were negatively associated with global social functioning: physical abuse: [n = 7, k = 7, r = −0.123 (95% CI −0.216 to −0.027), p < 0.001]; emotional abuse: [n = 6, k = 6, r = −0.138 (95% CI −0.226 to −0.047), p = 0.003]; sexual abuse: [n = 9, k = 9, r = −0.087 (95% CI −0.216 to −0.027), p = 0.012]; physical neglect: [n = 6, k = 6, r = −0.241 (95% CI −0.349 to −0.127), p < 0.001]; emotional neglect: [n = 6, k = 6, r = −0.226 (95% CI −0.323 to −0.125), p < 0.001].

Physical abuse [n = 6, k = 6, r = 0.230 (95% CI 0.119–0.334), p < 0.001], and sexual abuse [n = 5, k = 5, r = 0.126 (95% CI 0.042–0.208), p = 0.003] were positively associated with aggressive behaviour. Sexual abuse was also negatively associated with interpersonal relations [n = 7, k = 7, r = −0.102 (95% CI −0.189 to −0.013), p = 0.024] (see Table 2 and forest plots in SF1 in the supplement).

Meta-analyses of associations between childhood maltreatment and social cognition

No significant associations were found of associations between Overall CM (n = 6, k = 6, r = −0.003) and sexual abuse (n = 6, k = 6, r = 0.021, p = 0.679) and theory of mind. In addition, no significant association was found between overall CM and emotion processing (n = 6, k = 6, r = −0.105, p = 0.076) (see Table 2 and forest plots in SF1b and SF1d in the supplement).

Heterogeneity, meta-regression, and sensitivity analyses

Heterogeneity

Meta-analyses showed zero to low heterogeneity in results for most associations with a few exceptions: Associations between overall CM and independent living (n = 8, k = 8, I 2 = 87%, p < 0.001), interpersonal relations (n = 9, k = 9, I 2 = 52%, p = 0.036) and theory of mind (n = 6, k = 6, I 2 = 60%, p = 0.003), and between physical abuse and aggressive behaviour (n = 6, k = 6, I 2 = 54%, p < 0.001) showed moderate-high heterogeneity (see Table 2).

Meta-regressions

Results of meta-regressions for the association between overall and subtypes of CM and social outcomes are provided in ST8 in the supplement. Associations were largely independent from sample age, sex (% male), non-affective v. affective psychosis samples, FEP v. chronic PD samples, structured interview v. unstructured clinical judgment for PD diagnosis, CTQ v. any other instrument to assess CM, self-report v. clinical judgment to assess social functioning, behavioural data v. any other instrument to assess social cognition, and study quality (NOS rating) with a few exceptions.

Social Functioning: The association between physical neglect and global social functioning [n = 6, k = 6, β = −0.013, 95% CI (−0.021 to 0.002), p = 0.025] was weaker in males (v. females). The association between emotional neglect and global social functioning [n = 6, k = 6, β = −0.415, 95% CI (−0.826 to −0.004), p = 0.048] decreased with using self-report (v. clinical judgment). The association between Overall CM and independent living decreased with study quality (NOS rating) [n = 8, k = 8, β = −0.132, 95% CI (−0.023 to −0.038), p = 0.006]. The association between overall CM and interpersonal relations (n = 9, k = 9) was stronger in non-affective (v. affective) PD samples [β = 0.135, 95% CI (0.050–0.221), p = 0.002], and decreased with using CTQ v. any other instrument to assess CM [β = −0.138, CI 95% (−0.216 to −0.061), p = 0.001]. Finally, the association between physical abuse and aggressive behaviour (n = 6, k = 6) was stronger in males [β = 0.074, 95% CI (0.011–0.014), p = 0.021] and in non-affective PD samples [β = 0.245, 95% CI (0.094–0.396), p = 0.015], and increased with using self-report [β = 0.243, 95% CI (0.028–0.457), p = 0.027].

Social Cognition: The association between overall CM and theory of mind increased with using CTQ [n = 6, k = 6, β = 0.291, 95% CI (0.046–0.536), p = 0.020] and with study quality [n = 6, k = 6, β = 0.093, 95% CI (0.004–0.183), p = 0.042]. The association between overall CM and emotion processing increased with increasing age [n = 6, k = 6, β = 0.012, 95% CI (−0.001–0.024), p = 0.032].

Of note, as a general rule, estimates of heterogeneity based on n < 10 are not likely to be reliable (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein, Egger, Higgins and Smith2022a; Higgins & Thompson, Reference Higgins and Thompson2004).

Sensitivity analysis

Results of sensitivity analyses for the association between overall and subtypes of CM and social functioning and social cognition domains are provided in SF2 in the supplement. One-study-removed analysis did not change the patterns of most results with a few exceptions.

Social functioning: For the association between overall CM and independent living, the removal of Spence et al. [r = −0.109 (95% CI −0.213 to −0.003), p = 0.043] and Trauelsen et al. [r = −0.115 (95% CI −0.217 to −0.010, p = 0.032] led to a negative association, which was not observed with the inclusion of these studies (Spence et al., Reference Spence, Mulholland, Lynch, McHugh, Dempster and Shannon2006; Trauelsen et al., Reference Trauelsen, Gumley, Jansen, Pedersen, Nielsen, Haahr and Simonsen2019). For the association between sexual abuse and interpersonal relations, the removal of Akbey, Yildiz, and Gündüz (Reference Akbey, Yildiz and Gündüz2019) [r = −0.080 (95% CI −0.177 to 0.019, p = 0.115] led to a non-significant association.

Social cognition: For the association between overall CM and emotion processing, the removal of Quide et al. [r = −0.131 (95% CI −0.253 to −0.005, p = 0.042] and Pena-Garijo et al. [r = −0.131 (95% CI −0.232 to −0.028, p = 0.013] led to a negative association which was not observed with the inclusion of these studies (Pena-Garijo & Monfort-Escrig, Reference Pena-Garijo and Monfort-Escrig2021; Quide et al., Reference Quide, Cohen-Woods, O'Reilly, Carr, Elzinga and Green2018).

Assessment of publication bias

For associations between overall CM and independent living there was indication for publication bias (Egger's p = 0.004; 4 hypothetically missing studies identified), and the trim-and-fill adjustment method revealed a higher and significant corrected random effect estimate [r = −0.211, 95% CI (−0.315 to −0.103)]. For the association between physical abuse and aggressive behaviour (Egger's p = 0.002; 3 hypothetically missing studies identified), the trim-and-fill adjustment method revealed a lower (still significant) corrected random effect estimate [r = 0.142, 95% CI (0.031–0.251)] (see Table 2 and the funnel plots in SF3 in the supplement).

Narrative synthesis of moderators and mediators

Twenty-one of the included studies investigated effect moderation and eight studies investigated effect mediation between CM and social outcomes (see a summary of reported moderators and mediators in the included studies in Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Summary of the evidence on moderators and mediators between childhood maltreatment and social outcomes in psychotic disorders. Note. The figure summarises the findings of our narrative synthesis on effect moderators and mediators examined in the included studies. Moderators examined in the included studies are represented by circles/ovals (brick orange in online version). Mediators examined in the included studies are represented by rectangles (green in online version). The colour and thickness of the lines represent the robustness of the evidence, i.e., a stronger colour and thicker line representing major evidence (n ≥ 5). Lighter colour and thinner lines represent emerging evidence (n = 1). Dotted line and grey font indicate where evidence is lacking, and more research is needed.

Moderators

The most often investigated moderator was sex or gender (n = 6), with four studies finding a stronger association between CM exposure and impaired social functioning (Hjelseng et al., Reference Hjelseng, Vaskinn, Ueland, Lunding, Reponen, Steen and Aas2020; Lindgren et al., Reference Lindgren, Mäntylä, Rikandi, Torniainen-Holm, Morales-Muñoz, Kieseppä and Suvisaari2017) or social cognition (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019; Penney et al., Reference Penney, Pruessner, Malla, Joober and Lepage2022) in male than in female participants. Yet, Garcia et al., found poor social cognition in males and females but impaired social functioning only in women with FEP (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Montalvo, Creus, Cabezas, Solé, Algora and Labad2016). Kincaid et al. (Reference Kincaid, Shannon, Boyd, Hanna, McNeill, Anderson and Mulholland2018) found poorer theory of mind performance in males than females with schizophrenia.

There were also two studies supporting a moderating role of timing of CM exposure and emotional neglect, with CM during early childhood (0–6 years) specifically predicting theory of mind impairments in schizophrenia (Kincaid et al., Reference Kincaid, Shannon, Boyd, Hanna, McNeill, Anderson and Mulholland2018), and neglect experienced at 11–12 years specifically predicting social cognition impairment (Schalinski et al., Reference Schalinski, Teicher, Carolus and Rockstroh2018).

There is consistent evidence for a dose-response-relation (cumulative effect) for severity (n = 6) and number of CM experiences (n = 5) being linked to more pronounced social functioning or social cognition impairments in PD (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Kauppi, Brandt, Tesli, Kaufmann, Steen and Melle2017; Li et al., Reference Li, Li, Liu, Zhang, Tang and Wang2015; Lindgren et al., Reference Lindgren, Mäntylä, Rikandi, Torniainen-Holm, Morales-Muñoz, Kieseppä and Suvisaari2017; Penney et al., Reference Penney, Pruessner, Malla, Joober and Lepage2022; Schalinski et al., Reference Schalinski, Teicher, Carolus and Rockstroh2018) across all illness stages.

There are mixed results on the moderating effects of different types of CM (Bosqui et al., Reference Bosqui, Shannon, Tiernan, Beattie, Ferguson and Mulholland2014; Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Montalvo, Creus, Cabezas, Solé, Algora and Labad2016), with seven studies finding both physical and emotional neglect being the strongest predictors of diminished global social functioning (Gil et al., Reference Gil, Gama, de Jesus, Lobato, Zimmer and Belmonte-de-Abreu2009; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019), interpersonal relations (by anxious attachment) (Aydin et al., Reference Aydin, Balikci, Tas, Aydin, Danaci, Bruene and Lysaker2016), as well as impaired emotion processing (Kilian et al., Reference Kilian, Asmal, Chiliza, Olivier, Phahladira, Scheffler and Emsley2018; Rokita et al., Reference Rokita, Dauvermann, Mothersill, Holleran, Holland, Costello and Donohoe2021), empathy (cognitive trait) (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kwon, Min, Kim, Jin and Lee2019) and (affective) theory of mind (Vaskinn et al., Reference Vaskinn, Melle, Aas and Berg2021) in non-affective PD. There is also evidence (n = 3) on physical and sexual abuse being the strongest predictors of impaired interpersonal relations (Trotta et al., Reference Trotta, Murray, David, Kolliakou, O'Connor, Di Forti and Fisher2016) and aggressive behaviour in schizophrenia (Bosqui et al., Reference Bosqui, Shannon, Tiernan, Beattie, Ferguson and Mulholland2014; Hachtel et al., Reference Hachtel, Fullam, Malone, Murphy, Huber and Carroll2020).

Finally, there is little evidence (n = 1) for moderating effects of neurocognitive functions, with poorer executive function and physical abuse predicting aggressive behaviour in schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Lysaker et al., Reference Lysaker, Wright, Clements and Plascak-Hallberg2002).

Of note, none of the included studies examined the potential moderating role of the duration of illness or diagnosis type (e.g. affective v. non affective psychosis).

Mediators

There was some evidence (n = 3) for a mediation role of depressive symptoms between CM and impaired global social functioning in schizophrenia (Andrianarisoa et al., Reference Andrianarisoa, Boyer, Godin, Brunel, Bulzacka and Aouizerate2017), and occupational functioning in FEP (Ortega et al., Reference Ortega, Montalvo, Solé, Creus, Cabezas, Gutiérrez-Zotes and Labad2020), as well as emotion processing in PD (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Kauppi, Brandt, Tesli, Kaufmann, Steen and Melle2017). There is also evidence (n = 2) that maladaptive personality traits (Boyette et al., Reference Boyette, van Dam, Meijer, Velthorst, Cahn, de Haan and Myin-Germeys2014; Lopez-Mongay et al., Reference Lopez-Mongay, Ahuir, Crosas, Blas Navarro, Antonio Monreal, Obiols and Palao2021) may mediate between CM and social functioning and relations.

There is emerging evidence (from one study in each mediator), through the duration of untreated psychosis and poor premorbid functioning (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Andreassen, Aminoff, Færden, Romm, Nesvåg and Melle2016) in the association between CM and social outcomes. There is also evidence that conduct disorder may mediate between cumulative childhood adversities and adult propensity to aggressive behaviour (Oakley et al., Reference Oakley, Harris, Fahy, Murphy and Picchioni2016). Finally, Weijers et al., found that in those with non-affective PD, mentalising impairment mediates the relationship between CM and clinical outcomes (e.g. severity of negative and positive symptoms) but not between CM and social (dys)function (Weijers et al., Reference Weijers, Fonagy, Eurelings-Bontekoe, Termorshuizen, Viechtbauer and Selten2018).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated associations between overall and different subtypes of CM and different domains of social functioning and social cognition in adults with PD. Across the identified studies, we found an association between CM and impaired social functioning in PD. This finding is in line with the vast literature on clinical (Alameda et al., Reference Alameda, Christy, Rodriguez, Salazar de Pablo, Thrush, Shen and Murray2021), psychological, neurobiological (Bramon & Murray, Reference Bramon and Murray2001; Lim, Radua, & Rubia, Reference Lim, Radua and Rubia2014; Read, Perry, Moskowitz, & Connolly, Reference Read, Perry, Moskowitz and Connolly2001; Read et al., Reference Read, Fosse, Moskowitz and Perry2014; Teicher et al., Reference Teicher, Samson, Anderson and Ohashi2016) and neurocognitive (McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, Foulkes and Viding2022) alterations associated with CM that are likely to impact social functioning (Pfaltz et al., Reference Pfaltz, Halligan, Haim-Nachum, Sopp, Åhs, Bachem and Seedat2022). This finding is also in line with our initial hypothesis and with the only previous meta-analysis on the topic (Christy et al., Reference Christy, Cavero, Navajeeva, Murray-O'Shea, Rodriguez, Aas and Alameda2022). The associations were overall small (with weak effects), and findings differed essentially in consistency depending on the social domain considered, suggesting differential and specific effects. However, against our initial hypotheses and prior evidence suggesting a link between CM and social cognition (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Aas, Vorontsova, Trotta, Gadelrab, Rooprai and Alameda2021; Rokita et al., Reference Rokita, Dauvermann, Mothersill, Holleran, Holland, Costello and Donohoe2021), the results of our meta-analysis do not support, with the limited data existing at this stage, an association between CM and social cognition domains in individuals with PD.

In our study, the most consistent associations across overall and CM subtypes were found for the impaired interpersonal relations and aggressive behaviour in PD. This is in line with findings of a recent meta-analysis in affective disorders (Fares-Otero et al., Reference Fares-Otero, De Prisco, Oliva, Radua, Halligan, Vieta and Martinez-Aran2023), which may reflect a transdiagnostic effect of CM – particularly regarding difficulties in interpersonal behaviour and interactions. These difficulties might reflect early attachment-related problems, maladaptive internalised schemas (Messman-Moore & Coates, Reference Messman-Moore and Coates2007), and heightened sensitivity to interpersonal stress, which may have implications for problematic interpersonal adaptation, poor pro-social coping (e.g. overcompensation, avoidance, or surrender), help-seeking, and social withdrawal.

Furthermore, even though the risk of violence perpetration increases in individuals with a history of CM (Fitton, Yu, & Fazel, Reference Fitton, Yu and Fazel2020), our results should not be interpreted as generalised problems in prosocial behaviour or even as antisocial tendencies in individuals with PD and CM. In fact, the incidence of hostile or aggressive behaviour in PD is rather low (Faay et al., Reference Faay, van Os, van Amelsvoort, Bartels-Velthuis, Bruggeman and van Os2020; Fusar-Poli, Sunkel, & Patel, Reference Fusar-Poli, Sunkel and Patel2022). Further (longitudinal) research on associations between all CM subtypes and social interactions, considering comorbid personality traits, impulsivity, substance use, and environmental factors in PD is needed.

Our findings on the association between CM and poor social functioning replicate earlier work (Christy et al., Reference Christy, Cavero, Navajeeva, Murray-O'Shea, Rodriguez, Aas and Alameda2022) by showing that CM exposure relates to impairments in global measure of social functioning but not to occupational functioning. Of note, in our study, the finding on the negative association between overall CM and global social functioning in PD can be considered more accurate (than the previous meta-analysis) (Christy et al., Reference Christy, Cavero, Navajeeva, Murray-O'Shea, Rodriguez, Aas and Alameda2022) because our inclusion criteria was stricter as we only examined baseline data, without any intervention involved, and only in adults with PD.

Whether social functioning impairment precedes PD, or vice versa remains unclear. Recent evidence (McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, Foulkes and Viding2022) indicates that whilst social problems are likely to arise where a history of CM is present, they might also put the child at greater risk of further negative social experiences and interactions, such as greater maltreatment (e.g. bullying) later in adolescence, and limit future opportunities for social learning and support throughout the lifespan. Therefore, whether associations between CM and social functioning and interactions in PD may in fact be bidirectional should be examined in future prospective studies.

We also replicate previous findings supporting that physical (Gil et al., Reference Gil, Gama, de Jesus, Lobato, Zimmer and Belmonte-de-Abreu2009) and emotional neglect is associated with higher impairment in social functioning in PD (Christy et al., Reference Christy, Cavero, Navajeeva, Murray-O'Shea, Rodriguez, Aas and Alameda2022; Sideli et al., Reference Sideli, Schimmenti, La Barbera, La Cascia, Ferraro and Aas2022) than other CM subtypes. We found associations between sexual abuse and global social functioning, which is a novel finding maybe due to additional (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Andreassen, Aminoff, Færden, Romm, Nesvåg and Melle2016; Akbey et al., Reference Akbey, Yildiz and Gündüz2019; Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Montalvo, Creus, Cabezas, Solé, Algora and Labad2016; Gil et al., Reference Gil, Gama, de Jesus, Lobato, Zimmer and Belmonte-de-Abreu2009) and newly (Vila-Badia et al., Reference Vila-Badia, Del Cacho, Butjosa, Serra Arumí, Esteban Santjusto, Abella and Usall2022) included studies leading to bigger sample sizes to examine this association (that was not significant in the previous meta-analysis) (Christy et al., Reference Christy, Cavero, Navajeeva, Murray-O'Shea, Rodriguez, Aas and Alameda2022). The fact that findings generally replicated across subtypes of CM raises further questions about the underlying mechanisms that are altered by these diverse adverse childhood experiences, with likely broad consequences for social outcomes. Understanding these mechanisms could provide new intervention targets for individuals with PD and a history of CM.

We explored independent living, but did not find an association between CM and this important domain in people with PD (Ang, Rekhi, & Lee, Reference Ang, Rekhi and Lee2021). Altogether, it seems that CM exposure relates to social functioning impairment globally and to impaired specific domains, but not to independent living or occupational functioning. Of note, only overall CM was examined, and independent living was mainly based on living status while occupational functioning on employment status measures in the included studies. More studies are needed assessing associations between all CM subtypes and financial issues, and education or academic functioning in PD.

The suggested association between CM and social cognition in previous reviews (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Aas, Vorontsova, Trotta, Gadelrab, Rooprai and Alameda2021; Rokita et al., Reference Rokita, Dauvermann and Donohoe2018) was not confirmed in our study using a quantitative approach. Nonetheless, evidence in this area is based on a limited number of studies, with only two social cognition domains having sufficient data for meta-analysis. Further studies are needed on less explored domains such as attributional style/bias and empathy, and on not yet explored domains such as social perception or knowledge. While overall, there was no meta-analytic evidence for a relationship between CM and social cognition, some of the research summarised in our narrative review suggests that for specific subpopulations, there might in fact exist such a relationship. For instance, a relationship between CM and impaired social cognition has been observed (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019; Penney et al., Reference Penney, Pruessner, Malla, Joober and Lepage2022) that maybe stronger in males with PD (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Montalvo, Creus, Cabezas, Solé, Algora and Labad2016) and in certain development periods (Kincaid et al., Reference Kincaid, Shannon, Boyd, Hanna, McNeill, Anderson and Mulholland2018), or even found to be positive in FEP (Pena-Garijo & Monfort-Escrig, Reference Pena-Garijo and Monfort-Escrig2021). Differences in assessment instruments may explain the mixed results as studies using the same social cognition instruments (Hinting Task), but not the same trauma instruments (CTQ, CAMIR, and CECA-Q) found differing results. Future attempts to understand the socio-cognitive underpinnings of associations between CM and wider social functions in PD are critically needed.

There is evidence of a relationship between social functioning and social cognition in PD (Couture, Penn, & Roberts, Reference Couture, Penn and Roberts2006). Indeed, social cognition refers to the mental operations underlying social interactions (Green, Reference Green2016; Green, Horan, & Lee, Reference Green, Horan and Lee2015). There is also evidence supporting the link between adversity and poorer social functioning, and between social cognition and impairment in social functional outcomes in PD, especially in chronic stages (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Aas, Vorontsova, Trotta, Gadelrab, Rooprai and Alameda2021). Yet, in a recent systematic review of longitudinal studies on the relationship between cognition and social functioning in FEP, findings regarding social cognition were not unanimous (Montaner-Ferrer, Gadea, & Sanjuán, Reference Montaner-Ferrer, Gadea and Sanjuán2023). Taken together, there is still a gap in the literature regarding the role of social cognition in the association between CM (and its subtypes) and domains of social functioning, with a particular focus on social interactions, at different stages of PD.

In meta-regression analyses, we found some evidence for associations that may be stronger in non-affective samples – between overall CM and interpersonal relations, and between physical abuse and aggressive behaviour in males. There was some evidence of an association that may be weaker in males between physical neglect and global social functioning. However, findings stem from <10 studies precluding substantial conclusions. In line with previous work (Fares-Otero et al., Reference Fares-Otero, De Prisco, Oliva, Radua, Halligan, Vieta and Martinez-Aran2023) there was very little evidence for other moderation effects, and no consistent pattern. Future studies on moderating factors between CM (across all subtypes) and social functioning in PD are needed.

As a main finding, the number of relevant studies on associations between CM subtypes and social functioning, and social cognition was small. Given the major importance of CM for the course of PD (Bentall, Wickham, Shevlin, & Varese, Reference Bentall, Wickham, Shevlin and Varese2012; Schäfer & Fisher, Reference Schäfer and Fisher2011), and that CM is related to various characteristics associated with social impairment (McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, Foulkes and Viding2022; Pfaltz et al., Reference Pfaltz, Halligan, Haim-Nachum, Sopp, Åhs, Bachem and Seedat2022), our analysis shows that CM is understudied regarding social features in PD. CM is still less likely to be recognised in PD than other mental disorders (Read, Sampson, & Critchley, Reference Read, Sampson and Critchley2016). Clinicians themselves report that they are less likely to ask patients about CM histories if they are diagnosed with PD (Neill & Read, Reference Neill and Read2022; Read, Harper, Tucker, & Kennedy, Reference Read, Harper, Tucker and Kennedy2018; Read et al., Reference Read, Sampson and Critchley2016). However, 32 studies of the 53 included in this work were published within the last five years, which is in line with the growing interest and empirical findings regarding the importance of CM in PD (Kaufman & Torbey, Reference Kaufman and Torbey2019; Teicher, Gordon, & Nemeroff, Reference Teicher, Gordon and Nemeroff2022). This underlines the importance of further investigations (see SA8 in the supplement) of the relationship between CM and PD also regarding social outcomes.

Clinical Implications

The results of our meta-analysis suggest that it would be beneficial to systematically assess CM in routine care as a standard practice in (mental) health settings (Neill & Read, Reference Neill and Read2022). Clinicians should ask about all types of CM experiences (Read, Hammersley, & Rudegeair, Reference Read, Hammersley and Rudegeair2007; Read et al., Reference Read, Harper, Tucker and Kennedy2018), implement meaningful measures for its detection and provide effective service responses (Campodonico, Varese, & Berry, Reference Campodonico, Varese and Berry2022). Extra-training on CM and its social consequences for (mental) health professionals supporting those with PD is indicated. In addition to trauma-focused therapy (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, van Minnen and van der Gaag2018), our findings suggest that individuals with PD and different CM subtypes might benefit from additional treatment components, that target social circumstances (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Steare, Dedat, Pilling, McCrone, Knapp and Lloyd-Evans2022) and interactions (Faay & Sommer, Reference Faay and Sommer2021; Flechsenhar, Kanske, Krach, Korn, & Bertsch, Reference Flechsenhar, Kanske, Krach, Korn and Bertsch2022) and social (aggressive) behaviour. Interventions to counteract negative social anticipations might also be beneficial. Such approaches might be further supported by corrective, positive relationship experiences, including therapeutic engagement (Spidel, Lecomte, Kealy, & Daigneault, Reference Spidel, Lecomte, Kealy and Daigneault2018) and communication (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, John, Dooley, Healey, Cushing, Kingdon and Priebe2016). Improving social attitudes, building trust and positive beliefs about self and others (Fowler, Hodgekins, & French, Reference Fowler, Hodgekins and French2019), and reducing feelings of guilt and/or shame (Sekowski et al., Reference Sekowski, Gambin, Cudo, Wozniak-Prus, Penner, Fonagy and Sharp2020) might be valuable strategies to improve resilience in individuals with PD and CM at early illness stages (Arango et al., Reference Arango, Buitelaar, Correll, Díaz-Caneja, Figueira, Fleischhacker and Vitiello2022; Vieta & Berk, Reference Vieta and Berk2022). Psychoeducation on both PD diagnosis and the consequences of CM might also prove helpful for these individuals.

As suggested in our narrative review, depressive symptoms and maladaptive personality traits might be mediators in the pathway between CM and social functioning (Andrianarisoa et al., Reference Andrianarisoa, Boyer, Godin, Brunel, Bulzacka and Aouizerate2017; Ortega et al., Reference Ortega, Montalvo, Solé, Creus, Cabezas, Gutiérrez-Zotes and Labad2020) which is in line with previous research (Alameda et al., Reference Alameda, Golay, Baumann, Progin, Mebdouhi, Elowe and Conus2017; Kampling et al., Reference Kampling, Kruse, Lampe, Nolte, Hettich, Brähler and Riedl2022) and a model on the affective pathway to psychosis (Alameda, Conus, Ramain, Solida, & Golay, Reference Alameda, Conus, Ramain, Solida and Golay2022; Alameda et al., Reference Alameda, Rodriguez, Carr, Aas, Trotta, Marino and Murray2020), suggesting that treatment of sub-diagnostic levels of depressive symptoms and psychotherapy targeting personality functioning (Kampling et al., Reference Kampling, Kruse, Lampe, Nolte, Hettich, Brähler and Riedl2022) (and therapeutic relationship) (Picken, Berry, Tarrier, & Barrowclough, Reference Picken, Berry, Tarrier and Barrowclough2010) could help to improve psychotic symptoms, as well as social outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the rigorous methodology with the systematic search, study selection, and data extraction all performed by independent researchers, the inclusion of studies published in English, German, and Spanish, the evaluation of the quality of individual studies, and other key practices for meta-analysis.