The list of reports that punctuate the history of national or international public action is probably infinite. In this ocean float a few totems—including the Beveridge, Ohlin, Khrushchev, Radcliffe, Rueff-Armand, Meadows, Delors, Maekawa, and Stiglitz reports. Each in its own way, these reports marked their era by proposing a diagnosis and drawing up lines of action. The McCracken report, which is the focus of this article, is often seen as the symptom, the telltale sign, or the trigger of the neoliberal turn at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and, by extension, in Western economic cooperation.Footnote 1 Published in 1977, in a situation of stagflation (characterized by sluggish growth and high inflation) perceived as unprecedented and disconcerting in its magnitude, the McCracken report is generally considered a testament to the emergence of a new economic orthodoxy that marked the end or the weakening of the Bretton Woods regime. It is also seen as prefiguring the “Great Moderation”Footnote 2 that began in the mid-1980s, as well as certain elements of what came to be termed, in the 1990s, the “Washington Consensus.”Footnote 3 This interpretative reflex, whose methodological stakes transcend the neoliberal turn examined here, must be considered more closely before proposing a sociogenetic alternative capable of grasping the social dynamics—political, academic, and bureaucratic—that molded both the writing of the report and this reputedly critical economic and political juncture.

Backed by “neo-orthodox economics,” the “disciplinary state” would drive away the welfare state and its policies of active demand-side management by making control of inflation the primary macroeconomic objective, at the cost of high and persistent levels of unemployment.Footnote 4 This was the analysis proposed in 1978 by Robert Keohane, a rising star within the discipline of international relations in the United States, in an exceptionally long review article that has since fixed academic readings of the report in terms of the “neoliberal turn.”Footnote 5 Yet these interpretations rarely specify what they subsume under the term “neoliberal.” The British political scientist Stephen Gill at least has the merit of pointing out that this report—like another published in 1979 by the Trilateral CommissionFootnote 6—unambiguously advocated:

the need for tight control of national money supplies, cuts or restraint in government expenditures, and attempts to stop the rise in real wages. This would serve to reverse the downward trend in profits (and upward trend in real wages) which had taken place between 1968 and 1974, as well as to attack inflation. … The report also acknowledged that the costs of such a set of policies would be much higher, potentially permanent, levels of unemployment, and therefore the major capitalist states (mainly those in Europe) would have to jettison commitment to one of the central pillars of the postwar welfarist consensus. The changes involved an attack on wage indexation, and a general offensive designed to “liberalise” labour markets.Footnote 7

Quintessential in its neoliberal orthodoxy, the report thus took part in the “war against inflation” of the 1970s and testified to a durable shift in perceptions and methods at the OECD.

The participation of the chair of the expert group, Paul Winston McCracken, in the Mont Pelerin Society,Footnote 8 and his role as adviser to President Ronald Reagan a few years later,Footnote 9 have further reinforced this connection with neoliberalism. The McCracken report is overwhelmingly read in a particular way: certain aspects are selected and linked to the neoliberal victory, while others, nonetheless significant, are consistently excluded because they fit poorly with this scenario. For example, an important representative of the Chicago school—with “New Classical” tendencies—saw the report as a neo-Keynesian threat to his doctrine,Footnote 10 while the OECD was denounced by monetarists as a hotbed of Keynesianists.Footnote 11 Others, at the opposite end of the theoretical and political spectrum, considered the report as a doomed Keynesian proclamation or a failure of application, similar to the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act voted by the United States Congress in 1978.Footnote 12 Moreover, some sections of the report reaffirm the validity of conventional economic analysis,Footnote 13 or the possibility of Keynesian economic cooperation in terms of equilibrating the balance of payments and reviving global demand, both incompatible with the supply-side strategies of the 1980s.Footnote 14

From the moment of its publication, the interpretation of the report was in reality plurivocal, the picture less black and white, the “turn” more sinuous.Footnote 15 The subsequent success of neoliberalism has “unilateralized” our understanding of the document and the historical moment in which it was inscribed and which it contributes to depicting. This success also distracts us from the uncertainty, or even disarray, which characterized the situation for certain actors, as well as the continuities, compromises, and strategic retreats, the game of wait-and-see and positions that were more strident but which ultimately lost out. Integrating these into our analysis makes the report appear as a suspended moment in time, an instant when history seemed to hesitate in a longer chronology of the turn. But these remarks imply asking a question that has rarely preoccupied disciples of the “turn”: How did it take place? How did an intergovernmental organization, founded on the professed neutrality of its economic expertise—and whose most typical bureaucratic expression lay in the reports that it published on an almost daily basisFootnote 16—effect a political and economic transformation of such magnitude in the space of one such report? The rare attempts to answer this question make it possible to identify other impasses and issues at stake in the investigation.

Some, in the style of the (neo)realist school of international relations, consider that the report incontestably affirmed both the dominance of the United States within the OECD and, at the same time, the congenital heteronomy of this type of intergovernmental organization.Footnote 17 Specifying none of the concrete forms taken by this domination, this first explanation pays little heed to the attribution of the label “neoliberal” to the administration of Jimmy Carter, elected more than six months before the publication of the report. This administration had no declared monetarist in its ranks, let alone any “Reaganomist” or “supply-sider.” From its inauguration until 1979, it defended an international Keynesian approach, known as the “locomotive” strategy; during the 1976 presidential campaign, Senator Carter had denounced the Gerald Ford administration’s use of “the evil of unemployment to fight inflation.”Footnote 18 If the report marks the neoliberal turn and the dominance of the United States, this possible discrepancy with the new administration—and, by the same token, the relative independence of the OECD—deserves attention.

The second explanation, of a cognitivist type, parallels the official history and considers that “little by little, with frequent reversals and back-sliding, [the economists at the OECD] came to the conclusion that their Keynesian presuppositions were, if not wrong, inappropriate to a new economic environment.”Footnote 19 In this account, the accumulation of anomalies and empirical refutations of the Keynesian paradigm gradually brought it into doubt and eventually threw it off course; it would succumb to the test of reality. This intellectualist explanation validates the iconoclastic claim of monetarism against Keynesianism during this period. At the same time, it flows into the self-presentation strategy of an “expert” organization like the OECD, much more concerned than a standard bureaucracy with laying claim to a register of scientific legitimacy in which rational argument, the validation of hypotheses, and the rules of evidence were supposed to ensure consensus. This explanation converges with currents of research that seek to rehabilitate the role of ideas and learning in the analysis of public action, but which pay little or no attention to the social bases that constitute this “test of reality” or “disavowal by the facts.”Footnote 20 “Economic reality” and its causalities need interpreters.

The third, neo-Marxist explanation points to the new global alliance between governments and the business community, and takes the McCracken report as its resounding expression. This reconfiguration is said to have emerged to the detriment of the previous social-democratic alliance (incorporating New Deal industrialists in the United States), its foundations laid “by a collective effort of ideological revision undertaken through various unofficial agencies—the Trilateral Commission, the Bilderberg conferences, the Club of Rome, and other less prestigious forums—and then endorsed through more official consensus-making agencies like the OECD.”Footnote 21 This intentionalist and “sequentialist” explanation lacks empirical support concerning the action and articulation of the different agencies, whether official or not; it leaves little room for contingency, the unexpected effects of action, and the convergence of specific and contradictory interests.

What these explanations have in common is that they remain entirely subordinated to the “report” as a form, construing the institution or group as a homogeneous author and the document as a finished product, an opus operatum delivered over to interpretation.Footnote 22 Anything that relates to the “work in progress,” or to a modus operandi that stretched over three years, is left in the shadows: almost nothing has been written about who commissioned the report, the heterogeneous composition of the expert group, the role of the OECD Secretariat, the part played by government delegates and journalists, and so on.Footnote 23 Nor is much known about its most striking organizational properties. Internally designated as a “high-level” report, it engaged actors with a high political, bureaucratic, or academic capital and sought to mark an event on political and journalistic agendas. Also designated as a “horizontal” report, it strove for a transversal or intersectoral approach to the problems in question (unemployment, inflation, growth) by making usually compartmentalized sectors of the OECD work together.

To examine the dynamics of its production is to take administrative prose seriously in terms of the “reality of intellectual practices, forms of thought and ordering of the world, [and] bureaucratic routines”Footnote 24 of which it is composed. What is more, this method approaches the report as a social form linking or excluding a whole series of actors and universes in its fabrication, and through which international economic cooperation is deployed.Footnote 25 To what extent does this sociogenetic approach allow us to discuss concrete evidence—including what happened during the course of events—regarding these theses on the breakdown of the former social-democratic consensus, the weaknesses of Keynesianism, or US hegemony? How far does it enable us to exit the binary schema postulated by the notion of a turn, with the victory of one camp over another? Is one of the characteristics of the situation studied here not also to produce “labeling” struggles that polarize actors into homogeneous camps designated by “-isms” which are supposed to function as markers of shared belief (monetarism, Keynesianism, socialism, neoliberalism)?Footnote 26

This report, like many others, is not only a document to be read; it is a theater of political, bureaucratic, and academic operations that are there to be reconstructed. In its aims, this present article is closer to a vivisection than an autopsy. It puts the causal imagery of the turn on standby, controls its effects on the investigation, and is attentive to one of the key characteristics of the situation: the uncertainty about the economic future, coupled with the uncertainty felt by certain actors as to the analytical and prescriptive Keynesian frame and its pliability, as well as the uncertainty regarding the very role of international economic organizations. The usual anticipatory references are jammed, the political, economic, and social future is less easily decipherable, the previous operational solutions are questioned, and forms of de-objectification of the established are engaged.

Unaware of the the final version of the report, which the participants were yet to produce, and of the neoliberal outcome of events, which some sought to combat, this situation of structural uncertainty contrasts with the retrospective certainty of the neoliberal turn. The investigative approach adopted here uses a non-teleological perspective to grasp in action the “sense of the acceptable”—both individual and collective—of the actors involved in the collective writing of the report, a sense that, “by encouraging one to take account of the probable value of discourse during the process of production, determines corrections and all forms of self-censorship—the concessions one makes to a social world by accepting to make oneself acceptable in it.”Footnote 27 Tracing the sociogenetics of the report captures the interpretative and prescriptive struggles and makeshift solutions involved in a differentiated work of anticipating the acceptable, in a constant signposting of the social supports from which the key ideas proposed could benefit, or in a search for “plausibility structures.”Footnote 28 The dynamics of its production are analyzed as a situational logic through which the OECD Secretariat found itself exposed to issues and polymorphous external resources that collided and were measured against one another within this space. In the eyes of the participants, the use of the “report” form made the international power relations—whether political, bureaucratic, or academic—possible and objective. In what follows, the socially structured expectations of what was feasible, costly, or risky—that evanescent “causality of the probable”—are tracked through the process of collective composition based on four key moments: the commissioning of the report, the establishment of its framework, the constitution of the group, and the report’s crystallization.

In the Grip of the US Field of Power

The Internationalization Strategies of the Department of State and the Treasury in the Face of the Oil Crisis

The McCracken report was initially entitled the “Kissinger Growth Study.” Then secretary of state to the Ford administration (an office he had previously held under Richard Nixon), in May 1975 Henry Kissinger commissioned a comprehensive study on the slowdown in economic growth from the OECD Council, the executive body that brought together the foreign and finance ministers of the member countries. “In the midst of a recession, the most serious since the Great Depression of the thirties,” Kissinger set the objective of studying how to “return to sustained economic growth” through cooperative means, reinvoking the first goal assigned to the OECD in its founding convention of December 14, 1960. He also warned that “continuing inflation that destroys growth will be the arbiter of social priorities.”Footnote 29 This commission formed the second part of the US Department of State’s strategy to enroll the OECD in its objectives. The first had involved the management of the oil crisis, with the setting up of the International Energy Agency (IEA) at the OECD in 1974. The OECD Secretariat had distinguished itself as a forecaster from early 1973, in particular vis-à-vis the International Monetary Fund (IMF), by predicting the effects of a sharp rise in fuel prices on the economies of member countries.

Reacting to the devaluations of the dollar since Nixon had suspended its convertibility into gold in 1971, oil exporters—whose contracts are denominated in dollars—wished to maintain their margins by raising the price per barrel. In October 1973, using the US government’s support for the Israeli army against the Egyptian-Syrian coalition during the Yom Kippur War as a pretext, the countries of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) decreed an embargo on supplies to the United States, and then to Europe. Prices quadrupled between October 1973 and January 1974. In the OECD area, the inflation rate rose to an average of 15% in the spring of 1974, and to more than 30% in Japan and the United Kingdom. Interest rates reached 12% over the same period, while industrial production fell by 13% and the number of unemployed reached 15 million in 1975, or 5.5% of the civilian labor force, a postwar record. All these data for the period, produced by the OECD itself, objectified the “crisis” and construed it as an international problem.

In September 1974, to prepare for the visit of the OECD secretary-general, Emile van Lennep, to Washington, the head of the permanent mission of the United States to the OECD reported to Kissinger’s cabinet their discussions on how the organization could “be best used and adapted to meet US objectives in [the] current situation.” A veritable “acid test for international cooperation among Western industrialized countries,” the international macroeconomic situation could be broken down into three components: the energy question, the inflation/recession duo, and the monetary and financial question.Footnote 30 Van Lennep welcomed the future capacity of IEA member countries to move capital throughout the OECD area, enabling them to strengthen their negotiating position with OPEC member countries. In this respect, the Working Party 3 (WP3) of the OECD Economic Policy Committee (EPC)—bringing together the finance ministers from the Group of Ten (G10)Footnote 31—could, according to van Lennep, be further mobilized to raise funds on the financial markets and from the oil-producing countries, and to lend them—via the Bank for International Settlements (BIS)—to the OECD member countries most affected by price increases.

This international project for the public and negotiated recycling of petrodollars in order to curb inflationary pressures was similar to the one operating through the channels of the IMF, conceived in January 1974 by its new director-general, Johannes Witteveen, and supported by the Trilateral Commission—though this project could also be applied to developing countries. For some of the senior officials concerned, this involvement of international bodies in the definition of diagnostics and cooperative financial solutions represented the very pinnacle of their activity.Footnote 32 At the same time, for the United States the IEA represented a means to circumvent the rule of unanimity prevailing in the OECD’s Oil Committee and at the IMF, which allowed some countries, particularly France, the right to veto foreign policy concerning the oil-producing countries.Footnote 33 Nevertheless, the IEA’s International Financial Support Fund remained largely inoperative, while the Witteveen Fund was reduced by the US Treasury, and access to it limited to countries that did not introduce (or tighten) capital controls.Footnote 34

Securing the US Congress’s final agreement to such support funds in a period of acute budgetary deficit seemed beyond reach. Above all, the stated goal of Treasury secretary William SimonFootnote 35 was to maintain control over petrodollars, especially Saudi ones, as much as to reshuffle the cards of the international financial system, from the already fragile Bretton Woods system of public oversight toward a system based on financial markets flooded by petrodollars. As Eric Helleiner noted, “in a deregulated system, the relative size of the US economy, the continuing prominence of the dollar and US financial institutions, and the attractiveness of US financial markets all gave the United States indirect power via market pressure to, as Strange put it, ‘change the range of choices open to others.’”Footnote 36 The French government in particular fueled this growth in the financial industry by financing a growing share of its public debt and the disequilibria in its balance of payments at a low cost on private capital markets where liquidities were abundant. When it came to the question of intentionality and, more especially, the sole control of US decision-makers over the reemergence of global finance, it was therefore necessary to integrate other lines of action, whether governmental or not. Though the intention was not to bring down the whole Bretton Woods system, these measures nonetheless contributed to this outcome for different reasons and in an uncoordinated way.Footnote 37

On energy, monetary, and financial issues, the Department of State seemed no match for the Treasury, including in the secret bilateral transactions conducted with the Saudi government. Van Lennep advocated updating the remit of the OECD’s EPC—especially its informal bureau, restricted to the Big Seven,Footnote 38 which “would build on practice initiated during McCracken’s tenure as chairman of the CEA [Council of Economic Advisers, under President Nixon]”—or giving the OECD the role of supporting the Group of Five (G5), a meeting restricted to finance ministers and, from 1975, heads of state.Footnote 39 In doing so, he evoked the international coteries of financial bureaucracies to which diplomats, such as those of the Department of State, were relegated, circles with which he was well acquainted after his time representing the Netherlands as head of its Treasury. When Kissinger, for his part, supported the proposal of Labour chancellor of the exchequer Dennis Healey to increase the prerogatives and resources of the IMF during the British bond crisis of 1976,Footnote 40 he was opposing the Treasury, which championed the rigorous conditions of IMF loans: tightly controlled monetary growth and a drastic reduction in public spending.Footnote 41 The draft of Kissinger’s speech on growth at the OECD, which was leaked to the members of the US Economic Policy Board, made up of the Treasury, the Federal Reserve (FED), and the CEA of President Ford, aroused irritation.Footnote 42 The economic and financial sector of the US bureaucracy, in particular the Treasury, defended its international turf, or, better still, its internationalization strategies.Footnote 43

The Instrument that Derailed the General Theory

Kissinger left his post in January 1977, before receiving the report he had likely commissioned to counterbalance the Treasury’s international initiatives. The OECD Secretariat had not taken the initiative to convene a reflection group on the global stakes of economic growth. For Stephen Marris, the right-hand man of the OECD secretary-general during this period, the reason was simple: the OECD economists did not have anything new to offer regarding the international macroeconomic situation of “stagflation.” The presentation he delivered to his colleagues during a closed seminar organized at the OECD in 1983, on the occasion of his more or less precipitated departure, is interesting. Kissinger’s commission had obliged the Secretariat to break its own rules for the first time:

the classical rule in the use of expert groups is that you must have a clear idea of what you hope to propagate. You choose a group of people that you think are capable of swallowing it. You then produce a report that, with a little bit of luck, will have a big impact on opinion. Now we did not know what idea we wanted to produce.Footnote 44

In addition to this frustrated sense of organizational practice, imperceptible in the internal legal documents, Marris offered a retrospective explanation of the forces at work:

it was written at the precise point of inflection between the Keynesian and the new neo-classical consensus. And being a heterogeneous group it was absolutely inevitable that we tried to straddle the two schools, and of course being in that situation it is fairly inevitable that we fell in the middle and that we were viciously attacked from both sides.Footnote 45

The hardening opposition between these currents crystallized around one of the central instruments of postwar macroeconomic policy used in most OECD member countries: the Phillips curve.Footnote 46 Its academic and political prestige had been lent by the US economists Robert Solow and Paul Samuelson, both leading figures of the Keynesian-neoclassical synthesis—Samuelson had received the Swedish National Bank’s Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, dubbed the “Nobel Prize for Economics,” in 1970 for his work on the Keynesian theory of the cycle. The Phillips curve was considered to show that if unemployment increases, inflation slows, while if unemployment falls, inflation rises.Footnote 47 Accordingly, the political compromise advocated in the United States lay between full employment, defined as unemployment at around 4%, and price stability, defined as inflation at around 2–3%. The expansive budgetary policy pursued by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, particularly from 1964 onward, had seemed to confirm the possibility of such “fine tuning,” according to the lexicon then in use. But the simultaneous growth of inflation and unemployment, from the mid-1960s in the United Kingdom and the 1970s in the United States, appeared to call this delicate balance into question.

Stagflation preceded the oil crisis and, as a term, does not emanate from the academy, even though it was lent legitimacy by Samuelson’s use of it in the press in 1973.Footnote 48 It resulted from a position adopted in the British political field in 1965,Footnote 49 one that neither managed nor sought to question disinflationary approaches to income control, which were associated with Keynesianism and which at this time deliberately neglected monetary policy.Footnote 50 Stagflation did not automatically discredit Keynesianism. Interpreters were needed to successfully blame it for the “crisis.” Carried by a new generation of economists trained in neoclassical synthesis, the attacks against the Phillips curve redoubled in the American academic sphere. It served as a positioning lever to contest the whole Keynesian model in its Americanized form: mathematized, technocratized, and laced with a fierce anticommunism and antisocialism. Solow acknowledged post festum that there was, however, “little that is specifically Keynesian about [the Phillips curve], either historically or analytically.”Footnote 51 One of the little-noticed paradoxes of the political consecration of US Keynesianism during the 1960s is that it was almost contemporaneous with the academic consecration of its main competitor, gradually assembled under the label “monetarism,” with Milton Friedman at its helm.Footnote 52 Chairman of the American Economic Association in 1967, Friedman’s inaugural address indicted the Phillips curve even before stagflation hit the United States.Footnote 53 In 1976, during the writing of the McCracken report, he returned to this theme in the lecture he delivered when awarded his “Nobel Prize,” criticizing economists’ widespread support for the Phillips curve.Footnote 54

In each case, Friedman set himself up as a prophet and iconoclast, ridiculing a Keynesian orthodoxy created for the occasion. He took aim at policies designed to combat unemployment through budgetary or monetary stimulus, which would supposedly produce “adaptive expectations” among economic actors and in the medium term return unemployment to its “natural” level—beyond which it was considered voluntary—and inflation to a higher level. He argued that economic actors, especially wage earners, are only temporarily victims of the “monetary illusion” caused by inflation: they will seek to replenish their savings and thus reduce their consumption, which will ultimately affect the level of economic activity. The objective of full employment thus becomes too expensive and leads to a situation marked by the twin evils of inflation and unemployment, jeopardizing the Keynesian model as simplified in the Phillips curve. These critiques—which monopolized academic debates on expectationsFootnote 55 even though their radicality was quickly surpassed by that of the “New Classicists” of the Chicago school and their short-term “rational expectations” (the vertical Phillips curve)Footnote 56—tended to undermine ab initio any active demand-management policy using budgetary and ultimately monetary stimulus, as well as, more broadly, the macroeconomic interventionism associated rightly or wrongly with the work of John Maynard Keynes.Footnote 57

To address the issue of unemployment, the rational expectations model suggested on the one hand politically neutralizing intervention into monetary policy by setting rules for the stable growth of the money supply, and, on the other, focusing solely on the “imperfections of the labor market,” its “lack of flexibility,” or its “structural rigidities.”Footnote 58 This last theme, which was later grouped under the label “supply-side policy,” is dealt with marginally in the McCracken report, taking up only four to six pages out of nearly 400 (in contrast to the Jobs Study of 1994, which focused on this point). Yet this was enough to immediately attract criticism from the social wing of the OECD and Keohane in his review.Footnote 59 As for monetary matters, the report gave more room to the role of price expectations in the determination of interest rates, but remained circumspect about setting fixed rules for monetary growth, though it did consider that this could be a means to improve the regulation of demand. On this point, the OECD economists intended to refine their traditional Keynesian strategy.

The Keynesian Bet on Absorbing Monetarism

These economic knowledges were also state knowledges, part of a “literature of power”Footnote 60 that held the layman at arm’s length and centered on an essentially American world of acquaintance and competition. In a technical annex to the report entitled “The Expectation-Augmented Phillips Curve,” the economists of the OECD SecretariatFootnote 61 disputed the Friedmanian critique and the restrictive policy it implied, theorizing the expectations of economic actors faced with the implementation of a “restrictive government policy.” Its effect would be to “discourage investment and production, and hence lead ultimately to lower employment.”Footnote 62 It would thus bring the economy into an equilibrium where the factors of production were underemployed, and in return justify counter-cyclical action.Footnote 63 The body of the report signals, in this respect, that “insufficient public expenditure can also have adverse effects on growth and welfare and, via frustrated expectations, on inflation.”Footnote 64

Marris summarized the contribution that the information provided by the Secretariat had, in his view, made to the report: “it invented one of the most sophisticated versions of fine-tuning”Footnote 65 vis-à-vis the concept of the “narrow path” (fig. 1), a delicate route to recovery involving an unstable equilibrium between inflationary expectations and faltering demand.

You couldn’t go too fast, but you couldn’t go too slowly either, else there would be an [inflationary] spiral. … There was always a battle over whether the goal was a zero deficit, or whether, as Keynesians like me said, when there is a deficit in private savings in economies, then there may be a position of equilibrium, either a surplus or a budget deficit that balances the structural deficit in the private sector.Footnote 66

We had by then got a model in which we said if you are below potential output you mustn’t try and get back to it too fast because there is a kind of speed limit in going up, but you mustn’t stay away from it too long because then you will get negative effects on investment, on motivation and on productivity and it will be harder and harder to get back.Footnote 67

Figure 1. The “narrow path of growth”

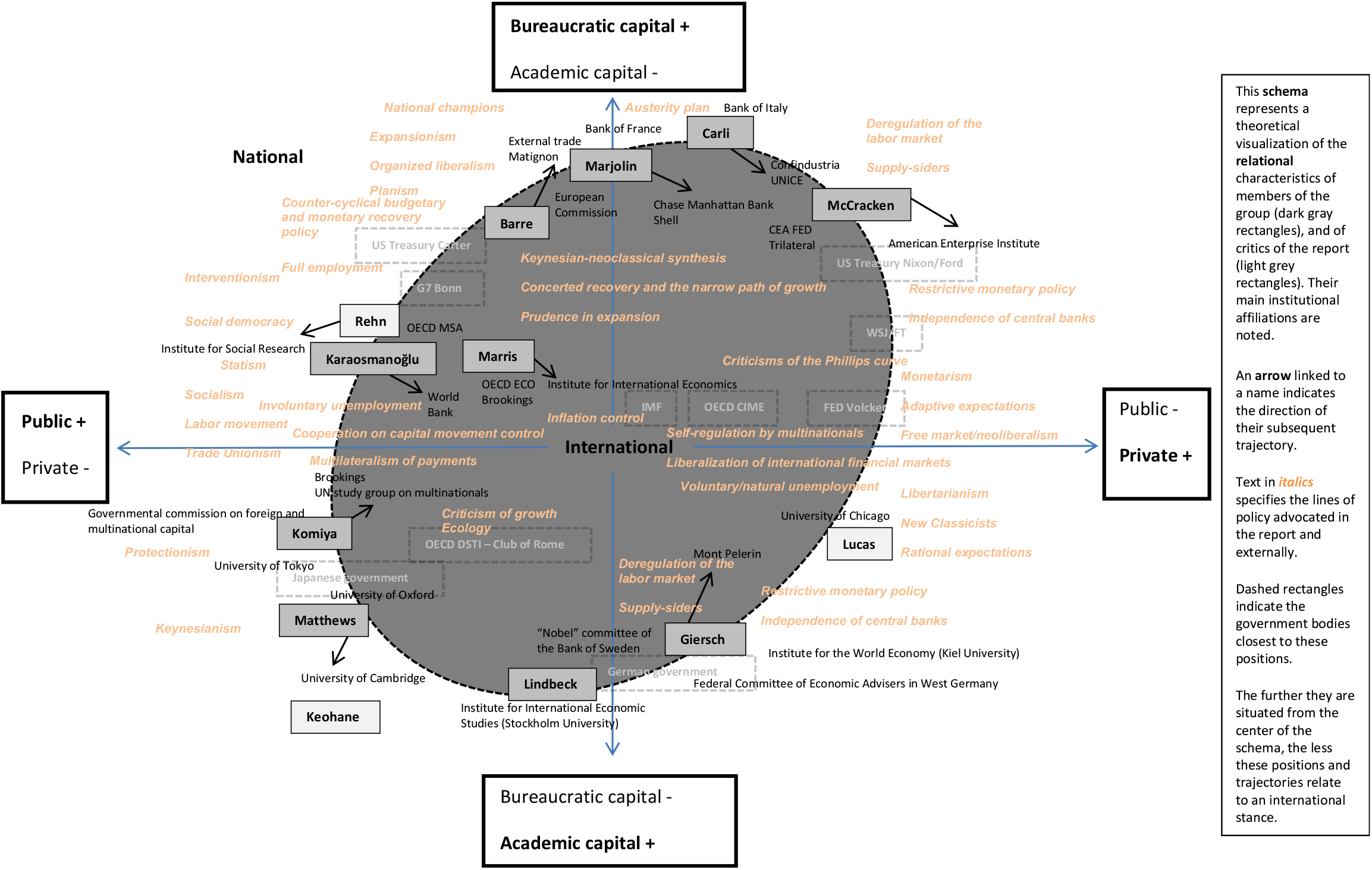

Figure 2. The staging of a closed group

Figure 3. Theoretical schema of the spatial positioning within the McCracken group

The difficulty of this strategy lay in the paradox—stated by Marris in 1970 in a more confidential OECD report—that linked the growth of inflationary expectations to the success of Keynesian economic policy: “once people began to correctly anticipate the consequences of government actions then the government’s actions would become themselves incapable of producing the desired result.”Footnote 68 In other words, the policy’s success removed any fear of a global recession from people’s minds and fueled inflationary behavior (overinvestment, price agreements, wage demands, etc.).Footnote 69 To restore price stability and maintain employment, the OECD recommended that governments eliminate “excess demand” and “be prepared where necessary to accept a temporary reduction in the rate of activity until there are signs that better price stability has been achieved.”Footnote 70 But the electoral risks of such a disinflationary policy were deemed too high.Footnote 71 To break inflationary expectations, the challenge was “how to convince people to behave as though a serious recession could happen without actually having to have one.”Footnote 72 The hope was that economic agents “would be so impressed by our determination to adopt these [anti-inflationist] policies that behavior would change without [our] actually having to administer the lesson.”Footnote 73

This was a deliberate Keynesian strategy to inflect expectations without having to act, very different from the methods of monetarists and New Classicists. This orthodox Keynesian strategy, which could not be acknowledged publicly if it was to produce effects, was largely overshadowed before being vanquished by these outsiders a few years later. As Marris observed, it had been “simplified in the pure form of monetarism when those wretched rational expectations people got into the game” with the unique solution of reducing the rate of monetary growth and letting unemployment rise.Footnote 74 Active demand-management policies were now caught in a vise between a risky and unutterable Keynesian position and an adverse and openly stated monetarist position—and this situation reinforced the central place of inflation and expectations as problems of economic policy.

Some self-declared Keynesians agreed with the OECD Economics Department’s strategy to recreate the fear of a real recession, including the former chair of the CEA under Lyndon Johnson, Arthur Okun (who held the position from 1968 to 1969 and was succeeded by McCracken),Footnote 75 and the British Labour foreign secretary Anthony Crosland, who evoked the specter of recession and the failed arbitration between inflation and unemployment at his party congress in 1976.Footnote 76 The Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal, who won the “Nobel Prize” in 1974 for his contribution to the theory of money (the same year as Friedrich Hayek), was also of this view, but stressed the institutional and societal factors of inflation and argued for the internationalization of the welfare state.Footnote 77 However, inside the OECD economists close to European social democracy and trade unionism, who also professed a form of Keynesianism, disputed this strategy. Gösta Rehn, head of the Directorate for Manpower and Social Affairs (MSA) from 1962 to 1973, and a leading figure, alongside Rudolf Meidner, of the Wicksellian Swedish postwar model linking fiscal policies, growth of real wages, employment policies, and state intervention, considered this strategy to be too politically risky because it would “be widely interpreted as an official recommendation for increasing levels of unemployment.”Footnote 78 Rehn’s fears were later confirmed: there had indeed been a shift from a disinflationary strategy to an anti-welfare policy.

What was at stake in this internal struggle at the OECD between the Economics Department and the Directorate for Social Affairs, respectively embodied by Marris and Rehn, was the definition of international Keynesianism employed by the organization. These struggles continued with the publication of the McCracken report seven years later. At a seminar of the social and trade union wing of the OECD, Rehn, now head of the Institute for Social Research at Stockholm University, judged that the report signaled the abandonment of full employment as a goal and depoliticized the issue of inflation by examining neither those responsible (in particular multinational firms) nor the redistributive conflicts of which inflation is the monetary expression.Footnote 79 In contrast, Rehn advocated disinflationary policies backed by an active employment policy, ruling out neither the creation of public jobs nor public intervention in business strategies. Meanwhile, the new British head of the Directorate for Social Affairs, James Ronald Gass, summoned to explain himself before the members of the McCracken group, attacked the report for its “total negligence of the social partners, unions, etc.” Underlining the degree of asymmetry and the impotence of the social wing of the OECD, his criticism, as for other reports, was expressed “in verse, quite poetically”: “it was a means of combat; there was such a dominance of macroeconomic thought.”Footnote 80

While there is no doubt that the center of gravity behind the commissioning of the McCracken report lay in the United States, the overall structure of the expert group cannot be reduced to one of unified, unilateral, and undisputed dominance. To the contrary, it lay at the frictional interface of the political, bureaucratic, and academic fields, themselves shot through by more or less conspicuous fault lines (Republicans versus Democrats, Department of State versus the Treasury, Keynesian-neoclassical synthesis versus monetarists). The dominant economic sectors at the OECD (Marris and, through him, the OECD Economics Department) took a position in relation to US debates, thus contributing to their internationalization. The asymmetry of such an internationalization can be measured in the proposed renewal of Keynesianism, which excluded or understated other Keynesian and institutionalist currents, whether Swedish, British, French, or otherwise. Some of these divisions emerged in the initial negotiations over how the report should be framed, while others appeared later on. The report form allowed for this confrontation of informational, bureaucratic, and political capital—in a sense, it objectified their differential value or exchange rate for the participants.

Bargaining over the Framing of the Report

A Secretariat Out of Step with Paul McCracken

To set up “the group of distinguished economists dealing with growth issues,” the agreement of the restricted bureau of the EPC—in which the “major countries” of the OECD were represented by their finance ministries—was immediately sought. The German delegation reacted coolly to the initiative. Its representative, Hans Tietmeyer, deputy secretary of state to the Ministry of Finance, head of the German delegation to the EPC until 1982, and future chairman of the Bundesbank, insisted that the study should focus on the issue of inflation and on “practical problems rather than embarking on futuristic, theoretical model-building along [the] lines of [the] Club of Rome.”Footnote 81 A think tank with a focus on forecasting, bringing together academics, senior business executives, and national and international officials, the Club of Rome had been created in 1968 in the corridors of the OECD (principally by the head of the Directorate for Science and Technology, Alexander King). It had attracted media and political attention through its far-reaching reports of 1972Footnote 82 and 1974Footnote 83 on the negative effects of industrialization, the environmental limits of the prevailing productivism, and the need for global cooperation to reduce (inter)national inequalities in the distribution of wealth and health. After supporting the initiative in its early stages, the OECD secretary-general, under pressure from the OECD Economics Department and the EPC, now officially considered there to be no conflict between economic growth and the protection of well-being and the environment, a position that is echoed in the report. In this respect, Kissinger’s commissioning of the report reinstated economic growth as the focus of political objectives.

The directors of the main OECD departments attended the first preparatory meeting held at its headquarters a few weeks later, as did McCracken. One of the four deputy secretaries-general, the seconded inspector-general of finances Gérard Eldin,Footnote 84 who chaired the meeting, stated that the group wished to offer governments solutions “to regain control of the economy.” The deck of economic policy cards was to be reshuffled: “What rate of growth should be aimed for? … To what extent does the market system still work? … What new instruments are needed nationally and internationally?”Footnote 85 The OECD Secretariat relayed government questions in a multilateral context in which the organization’s “vertical” divisions into sectoral departments or directorates (economics, industry, social affairs, science, etc.) seemed occasionally to be lifted in favor of a “horizontal” discussion pooling documentary resources and objects of inquiry.Footnote 86 But this could not mask the objective hierarchy between the departments in terms of staff, budget, and information capital, especially when it came to statistics. The organizational protocol was another reminder of this hierarchy, in that it foregrounded the Economics Department and the issues associated with it to the detriment of other elements, especially the “social” issues that for the OECD economists posed a problem of quantification and were not always fully integrated into the debates.

Unsurprisingly, all of the participants saw the group as an opportunity to overcome the bureaucratic constraints that usually weighed upon OECD working committees incorporating government delegations. Moreover, the group’s work was not “to duplicate [that] of the Secretariat,” which was “more rigorous [and] should not use any particular model.” It could be “similar to the Rey group, re-examining the economy from a long-term perspective but without a precise time horizon.”Footnote 87 Despite commitments made on the future autonomy of the group and a comfortable provisional budget,Footnote 88 however, the range of questions and mere logistics of the undertaking meant that the Secretariat would play an important role in both the provision of information and the drafting of the report. The timetable was certainly tight: an interim report was to be submitted to the meeting of ministers at the OECD Council in June 1976; only five or six one-week meetings were scheduled, during which the group could meet alone, with the Secretariat, or with external actors. Marris and his collaborators were the key figures in the drafting process.

McCracken intervened little during the first meeting, simply clarifying that the group should not limit itself to the analysis of “economic factors [but] must examine a very difficult problem facing policymakers, namely the fact that confidence for addressing the economic situation has evaporated.” In short, it would have to deal with factors that he himself seemed to judge extra-economic.Footnote 89 Two days later, however, the letter he sent to the OECD secretary-general cut short these more abstract discussions and stated that the aim was a necessary adaptation of Keynesian analytical tools. McCracken no longer had any qualms in stating that “the conventional wisdom of the Keynesian tradition does not seem to be adequate as new economic forces produce unanticipated, fundamental, persisting disequilibria in the industrial world’s economies.” These disequilibria were not limited to the “discontinuous jump in oil prices or short crop yields.” McCracken went on to negotiate the composition of his group: “I would assume that there would be a general sympathy for favoring primary reliance on the market system for organizing economic activity rather than for the state organized economic systems.”Footnote 90 The scope of acceptable profiles was restricted to a non-interventionist way of thinking: the socialization of markets through (para)state authorities was rejected a priori.Footnote 91 By thus bringing into play his own participation in the group, McCracken negotiated with van Lennep every step of the way. This proximity and self-assurance could be traced back to the economist’s exceptional career path.

A Chairman of Syntheses

McCracken was born in 1915 into a Republican family of Iowa farmers, with an uncle who was an economics teacher. His youth was marked by the Great Depression, to which he attributed his interest in economics: “We didn’t have to read GNP statistics, which of course did not exist; the problems were all around us.”Footnote 92 After graduating from William Penn College in Oskaloosa in 1937, he gained a place at Harvard University and graduated with a Master’s in Economics in 1942. He was immediately recruited to the Department of Commerce, where from 1942 to 1943 he officiated in a market economy organized for war. From 1943 to 1948 he worked at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis as a financial economist and then as director of research, at the same time completing his doctorate at Harvard. He subsequently moved to the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan, where he remained until his retirement.

Cofounder, in 1952, of the American Enterprise Institute (AEI)—a conservative think tank whose legitimacy was initially fragile, but which provided contingents to Republican administrations, and which Friedman joined in 1956—McCracken was part of the Republican intellectual establishment in economic matters. As chair of the CEA under Nixon from 1969 to 1971, he took part in the WP3 meetings at the OECD,Footnote 93 where he met van Lennep, who chaired the working group in his role as representative of the Dutch Ministry of Finance before being appointed OECD secretary-general in October 1969. Van Lennep had already consulted McCracken on the question of inflation before Kissinger’s request. Joint-conference rapporteur on this theme to the US government and to Congress, McCracken prepared parts of President Gerald Ford’s speech of May 8, 1974.Footnote 94 In response to van Lennep, he stated that “these distortions and displacement effects are highly specific [to national configurations]. It is not, in short, wages vs. profits, but one wage earner relative to another.”Footnote 95

At the CEA under Nixon, McCracken denounced the inflationary nature of the wage increases granted to workers in the automobile industry and was hostile to job-creation programs in the public sector.Footnote 96 At the same time, he extended unemployment benefits and exempted the poorest in society from federal income tax. Although in 1969 he had argued that in “our economic strategy there is no room for direct control over prices and wages[,] the market economy has its own morality that does not suffer waiting,”Footnote 97 in 1971 he resolved upon a new economic policy of wage freezes and price control, less out of doctrine than “pragmatism” or “realism,” as he liked to present it (including to himself).Footnote 98 This was an “enormous disappointment” to Friedman, for whom it falsified the “natural” fixation of prices necessary for the market to function properly.Footnote 99 On monetary issues, McCracken did not have much weight compared to the FED led by Arthur Burns (Friedman’s thesis supervisor), who had practiced an expansionist monetary policy since 1971. Yet, like Friedman, he wished to neutralize its effects on expectations by establishing a fixed growth rule.Footnote 100 He harbored strong reservations about the generalized floating of currencies (especially the deutsche mark), which he considered “too uncertain and risky.”Footnote 101

The divisive question of fixed or floating exchange rates reached right up to the Mont Pelerin Society itself,Footnote 102 where in 1972 McCracken took part in a meeting attended by Friedman, Irving Kristol, Gordon Tullock, Karl Popper, Gary Becker (“Nobel Prize” in 1992), Gottfried Haberler, and Herbert Giersch. The latter went on to join the McCracken group and succeeded James Buchanan (“Nobel Prize” in 1986) as chair of the Society in the 1980s.Footnote 103 McCracken does not seem to have participated in any of this international think tank’s subsequent meetings, but he did attend those of the Trilateral Commission, of which he had been a member since its creation in 1972. There he rubbed shoulders with John Kennedy’s chief economist, the Keynesian Walter Heller, Carter, the Democratic Governor of Georgia, and Alan Greenspan, the chairman of Ford’s CEA and, as such, a member of the OECD’s WP3—they were later joined by twenty-six members of the Carter administration. Upon leaving the CEA, McCracken joined the cohort of economists (including Friedman) appointed by the Wall Street Journal to produce a monthly editorial, to which he was a contributor for ten years.

Without construing the viva panel of his PhD thesis in economic trigonometry as a harbinger of his future career, its three members nevertheless represented a miniature version of the triptych that structured the field of US postwar economics at Harvard. Alvin Hansen, who had trained McCracken, was a leading Keynesian economist and a Democrat, whose key role in importing Keynes’s ideas into the United States meant that he was well positioned as an intercessor during the Bretton Woods negotiations. Joseph Schumpeter, an Austro-Hungarian who had migrated to the United States in the 1930s, was an elitist and liberal economist. Less well-known than Hansen at this point, he was the archetypal “conservative intellectual”Footnote 104 beset by pessimism as to the future of capitalism in the face of socialism. Finally, Gottfried Haberler, an economist of the Austrian school, had attended Ludwig von Mises’s private seminar in Vienna (the Mises-Kreis), and since 1934 at the League of Nations had developed a theory of the economic cycle and international trade opposed to that of Keynes. He also participated in the Mont Pelerin Society and the Cato Institute, before joining the IEA. McCracken’s originality was that, in a form of allodoxia, he could be perceived as belonging to all three poles at once.

From the report that now bears his name, he retained the expression “Non-accommodating monetary and fiscal policies”:

if you want to limit inflation, you just have to confront it frontally. Then, I remember the meeting in Paris with foreign [ministers] I guess … or finance ministers, and I had to make a report. I think it was almost the case, somebody says “well, it’s obvious!” There was almost a change in thinking [toward] a more realistic point of view.Footnote 105

Marked by a form of prudence, “gradualism,” or centrism far removed from the peremptory outbursts of Friedman, McCracken had not provoked any controversy in the spheres of academic macroeconomics, the intellectual side of business lobbying, or the senior echelons of the US economic administration. In 1975, he thus seemed to be the man of the moment at the OECD, embodying a point of convergence between opposing forces.Footnote 106 Although his interlocutors enjoyed imagining him in a certain way (“eclectic,” “right-wing Keynesian,” “Friedmanian”), McCracken above all brought sufficient bureaucratic, political, academic, and journalistic capital to the overarching—and exclusively American—structure to be allowed to develop a strand of the new global macroeconomic consensus at the OECD.

The Forced Extraversion of the Expert Group

Unexpected Guests: The US Congress, the Financial Times, the G6, and the IMF

Once McCracken’s intentions had been announced to the secretary-general, invitations were issued. The highest ranks of the OECD were tasked with activating this relational capital: the secretary-general and the director of the Economics Department invited Giersch, Guido Carli, and Raymond Barre during the summer of 1975. In a continuation of existing asymmetries, the Directorates for Social Affairs and Science and Technology were excluded from this intermediation. The letters sent out mention neither Kissinger’s commission nor McCracken’s political desiderata concerning the necessary “adaptation” of Keynesianism and the adherence of the invited economists to “market-oriented” positions. This letter-writing campaign was accompanied by meetings. Charles Wootton, the OECD’s American assistant secretary-general, organized a lunch “to allow Prof. McCracken and the Secretariat to discuss matters with a senior representative of the Congressional Joint Economic Committee, who had heard talk of the group’s establishment and wanted to be kept informed.”Footnote 107 This type of meeting gave certain senior OECD officials first-hand knowledge of the perceptions, expectations, and conflicts within US economic institutions. The archives suggest that the US Congressman was the only one to receive this kind of attention, at the moment when the bill on full employment presented by the left wing of the Democratic Party was being reintroduced.

Two years later, this bill led to the Humphrey-Hawkins Act. This set out a new mandate for the FED, which was now obliged to justify its strategy to Congress in terms of the same objectives as the future McCracken report: full employment (defined as unemployment at 4–4.5%) and price stability.Footnote 108 It was also during this period that the House Banking Committee of the House of Representatives, chaired by Henry Reuss, played a decisive role in blocking international monetary matters by opposing any multilateral adjustment measure that would restrict the United States. The United States enjoyed an unparalleled monetary privilege under the floating exchange rate system, in which the distribution of adjustment costs between countries with a balance of payments surplus, and those with a deficit, was decided by the fluctuations of the currency markets. To ward off speculative attacks on the franc and financial instability, the French Treasury (represented by Jacques de Larosière) campaigned against the US Treasury (represented by Edwin Yeo) for a return to a (Bretton Woods-type) fixed exchange rate system authorizing multilateral monetary adjustments (multilateralism of payments), in which the OECD’s WP3 had hitherto played an important role.

Thus not all political and bureaucratic fields carried the same weight when it came to structuring the calculations and expectations of the probable made by the OECD agents and McCracken. The same was true of the journalistic fields. As soon as the group’s composition was almost stabilized, the press had to be contacted. Yet the working title of the report—“Policies for non-inflationary economic growth”—remained too dull, and the alternatives unconvincing.Footnote 109 A leak precipitated the planned “public relations” program. Although not all the prospective members had given their agreement, and no official communiqué had been issued, an article in the Financial Times penned by Samuel Brittan, a prominent editorialist and future supporter of Thatcherism, unveiled the creation and composition of the group.Footnote 110 At the OECD, the reactions were ambivalent. While the assigned objectives and PR success were not disputed, the article dampened any element of surprise.Footnote 111 More seriously, since its confidentiality had disintegrated just as the group’s composition was being finalized, it was now extremely costly for the Secretariat to exclude any of the members mentioned in the article. The leak weighed heavily in the internal negotiations.

The Financial Times article evoked the parallel launch of a group led by the secretary of state of the German Ministry of Finance, Karl Otto Pöhl (future chairman of the Bundesbank from 1980 to 1991), which also featured Raymond Barre, tasked with preparing the first summit of the G5 heads of state. This meeting was held in Rambouillet in November 1975 (as the G6, because the Italian government was ultimately invited), and, despite van Lennep’s insistence, did not include the OECD. In their discussions, the heads of state advocated more cautious circumstantial stimulus policies at the risk of higher unemployment rates, following the principle of “prudence in expansion.” While an economic recovery had been taking shape since 1975, in June 1976 the OECD Council took up the same theme—and the concept of the “narrow path” developed by the Secretariat seems to have been its direct technical translation. Rambouillet also made concrete the results of the bilateral negotiations between France and the United States concerning the international monetary system. This was manifested the same year by an amendment to article 4 of the IMF statutes—via the signature of the Jamaica Accords—stipulating not a return to fixed exchange rates, but the transition to the “stable floating exchange rate system” desired by the US Treasury. On the one hand, states were authorized to intervene on foreign exchange markets to prevent “disorderly” market conditions; on the other, they were prohibited from introducing competitive devaluations. The IMF now exercised a “firm surveillance” over member states’ exchange rate policies, obliging them to provide all necessary macroeconomic information.Footnote 112

Ties with Economic Bureaucracies and the Business Community

A few weeks after the Financial Times episode, it was decided that McCracken alone was authorized, “for political reasons,” to meet the press.Footnote 113 The idea was to establish a principle of inaccessibility and homogeneity, so as to prevent dissonant voices. Male and multinational, the group’s members were presented in the OECD’s press releases as experienced men; their academic degrees, exclusively in economics, were highlighted so as to underline both their intellectual competence and their academic disinterestedness. The main member countries of the OECD were represented in the group and when, in January 1976, Barre was appointed minister for Foreign Trade, he was replaced at short notice by another Frenchman, Robert Marjolin.Footnote 114 The same rule applied when Miyohei Shinohara was succeeded by Ryūtarō Komiya.Footnote 115 With the exception of Robin Matthews,Footnote 116 the group’s members had all accumulated social and bureaucratic capital on the international stage: of the nine, six had spent time at the OECD (or the OEEC), three at the European Economic Community (EEC), three at the World Bank, one at the United Nations (UN), and another at the IMF. At the national level, government agencies involved in supporting decision-making and the production of studies were overrepresented, with seven out of nine members involved in organizations such as the French Planning Commissariat, the British Social Science Research Council, the German Committee of the Economic Council, the US CEA, and so on.

This “intellectual” bureaucratic capital based on technical and political expertise (of the adviser-to-the-prince type) was far removed from the bureaucratic capital founded on seniority within an administration and the exercise of managerial functions. Economics-related government departments (foreign trade, industry, the economy) and central banks (FED, Bank of Sweden, Bank of Italy, Bank of France) were also overrepresented. By contrast, no member of the group had pursued a career, or even part of one, in a “social” ministry or an international organization dedicated to “social” matters, such as the International Labour Organization (ILO) or the UN’s Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). None, moreover, had run for parliamentary office. With the exception of Matthews and Komiya, the “purest” academics and the most Keynesian members of the group, all had held government positions. These were recalled in the press files without specifying the political orientation of the—mostly right-wing—governments in which they had served, thus depoliticizing them as “wise men” and giving precedence to the official character of their function. Professional experiences in the private sector or in the representation of business interests were also omitted. For example, there is no mention of McCracken being a member of the board of directors of the IEA, or that Carli,Footnote 117 governor of the Bank of Italy from 1960 to 1975, had become chairman of the main confederation of Italian employers, Confindustria, in 1976.

Nor is there much that reveals the economists’ theoretical allegiances, an omission that once again presented the economic disciplines as a united front to the outside world. To the contrary, however, at the 1983 closed seminar of the OECD mentioned above, MarrisFootnote 118 described:

an extraordinary heterogeneous group of people ranging from dyed-in-the-wool Keynesians like Matthews [to] maverick supply siders like GierschFootnote 119 and eclectics like LindbeckFootnote 120 and McCracken, who although in certain senses was a Keynesian, was under very heavy pressure from monetarists at home. … So inevitably we got a sort of committee document result.Footnote 121

The academic qualifications and official functions of the members, combined with their various nationalities, implied the group’s independence and overarching vision, and participated in this construction of meta-partisan attributes. This was the price of expert utterance, that is, the establishment of an asymmetrical configuration pitting scholar against layman, pedagogue against pupil.Footnote 122 These varied but homogeneous trajectories inscribed the group and the institution in tacit and incorporated forms of interdependence that cannot be reduced to interactions alone. And although the director of the Economics Department, John Fay, considered that the group should maintain a distance from the “social partners”Footnote 123 represented at the OECD by the Business and Industry Advisory Committee (BIAC) and the Trade Union Advisory Committee (TUAC), the nature of the group and its initial stances suggest that in reality they were much closer to the business community than the unions.

The Conflictual Crystallization of the Report: From the Probable to the Probative

An Anxious Public Scribe Faced with a Highly Divided Group

In its framework paper on the economic crisis, the Secretariat evoked a wide range of factors: access to raw materials, the weakening of the propensity to invest, the Vietnam War, but also “the distribution of basic income between labour and capital; income differentials between different groups of workers; non-wage demands of households, such as social security, health insurance, and even such aspirations as ‘participation,’ ‘quality of life’ and yet others.”Footnote 124 Though it distinguishes “different schools of thought (which are not necessarily mutually exclusive),” no particular author or academic label (Keynesianism, monetarism, etc.) is cited. The analysis does not focus on the growth of the money supply, the oil crisis, or the labor market’s lack of flexibility. Rather, the note calls for a “thoroughly new approach” in order to place more emphasis “on the qualitative rather than quantitative aspects”: assistance to marginalized groups, incentives to retire, and a reduction in working time. It is possible to surmise from this note the ongoing research that was being conducted into social indicators.Footnote 125

Invited to put forward their own opinions on the situation, the members of the expert group did not explore this idea in more depth. Indeed, the group seems to have been far more closed in the scope of its questioning than the Secretariat. No one wished to reduce the economic situation to the inflation of fuel prices, though some openly identified calls to share wealth, the power of trade unions, and post-May 1968 political mobilization as its main causes. Giersch and Lindbeck thus ruefully accepted the abandonment of full employment and “oversold” demand-management policies. They targeted the growth of the welfare state and advocated from the outset the removal of “employment guarantees to groups of workers who abide [by] wage guidelines; norms for monetary policy, etc.”Footnote 126 These judgments directly echoed the themes of the “ungovernability” of Western societies and the “excess of democracy,” voiced the same year at the Trilateral Commission:

it becomes difficult if not impossible for democratic governments to curtail spending, increase taxes, and control prices and wages. In this sense, inflation is the economic disease of democracies. … The effective operation of a democratic political system usually requires some measure of apathy and non-involvement on the part of some individuals and groups.Footnote 127

Marris raised concerns, in his internal memo to the secretary-general, that the group was “a bit too traditional and conservative.”

Other divisions arose within the group, which were only partially aligned with the Keynesian/New Classical opposition evoked retrospectively by Marris. One thing they had in common however was that they never called into question the econometric and statistical apparatus used by the OECD SecretariatFootnote 128 —for example, the comparability of inflation and unemployment rates—thus reinforcing its key role at the informational level. Atilla KaraosmanoğluFootnote 129 harshly criticized the pre-report for its lack of attention to developing countries, even though he failed, it seems, “to provide drafts himself.”Footnote 130 He nevertheless succeeded in having his critique appended to the final report. In it he states that he does not share “the degree of faith expressed by the majority of the Group in the working of the market.” He points to a factor that he considered largely underestimated, especially when compared to the emphasis placed on the “inflationary wage demands of organised labour”: the “possible destabilizing effects in the behaviour of big international firms.”Footnote 131

On this point, the main text of the report welcomes the OECD Council’s adoption in 1976 of the “Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises” prepared by the Committee on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises (CIME). Established in 1975 at the initiative of the United States, this committee advocated the self-regulation of the sector and sought to counter the draft regulation introduced in 1972 by the Group of 77 (G77) at the UN and the ILO, following the International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT) scandal in Chile. Although the report recognizes that “some companies have abused their political power in small countries,” it immediately states its opposition to the “unjustifiable expropriations” embarked on by some governments.Footnote 132 Karaosmanoğlu called for binding international regulation of the sector, as did many trade unionists and social-democratic, socialist, and communist economists.Footnote 133 As their financial operations become more international, the big firms were able to escape the regulation inherited from Bretton Woods by turning to the deregulated Euromarket of the City of London. A de facto alliance in favor of international financial liberalization established itself between these firms and the financial sector.

Likewise divided on the degree of independence to be granted to the central banks, the group was split even further concerning the scale of the desired recovery and especially its international coordination: “expansionists” such as Marjolin, partly supported by Matthews, Karaosmanoğlu, and Komiya, pitted themselves against the supporters of a moderate recovery: McCracken, Giersch, and Lindbeck.Footnote 134 While their respective countries each had a balance of payments surplus and domestic economic recovery would, to their mind, lead to new inflationary pressures, Giersch and Komiya opposed the coordinated recovery package put forward in the report, again in an appended critique that implicitly referred to West Germany and Japan.Footnote 135 Komiya, for example, stated that “one should not request any [country] to deviate from its optimal recovery strategy in order to take the lead in the worldwide demand expansion or contraction.”Footnote 136 Giving free rein to his ethos as an international senior official (which would precipitate his downfall a few years later), Marris complained to the secretary-general of the general conformism of the group due to the lack of “competence” and “astonishingly nationalistic” views of its members on “nearly all the issues discussed.”Footnote 137

Marris also expressed his apprehension: the overall draft made sense, but its reception was becoming problematic following the election of a Democrat in the United States, especially on the question of economic recovery. He did not rule out the possibility that the report might be “rejected by the new administration” at the June 1977 Council of Ministers. The head of the Office of Forecasting and Evaluation within the cabinet of the OECD secretary-general nevertheless cast doubt on the political nature of such a rejection by the United States, as well as on Marris’s ability to reconcile opposites in the final drafting of the report:

If Schultze and Blumenthal reject this report and take what appears to be a more “expansionist” position at the Ministerial (and given the dissension in the ranks of the McCracken group … that would not be too surprising), I think it will be because of some honest differences in their understanding from that of Professor McCracken of how the modern economy functions. These differences … centre around determinants of investment and the role of expectations. … I simply wish to temper your optimism about the possibility of bridging this gap with felicitous compromise language.Footnote 138

McCracken contacted the new chair of the CEA, Charles Schultze, and planned to meet the undersecretaries of state for Economic Affairs (Richard Cooper) and Monetary Affairs (Anthony Solomon), or even the secretary of the Treasury (Michael Blumenthal) in Washington. His aptitude as a mediator could now be used to make last minute adjustments and thus protect the OECD. To the contrary, however, these meetings revealed a difference in opinion on the global recovery plan that McCracken clearly intended to have included in the report. This discrepancy placed the Secretariat in a bind and entailed further corrections.

The Last Redrafts, or the Bandwagon Effect

Van Lennep was concerned for the OECD due to the “politically very sensitive” nature of the problem. The Secretariat was out on a limb and any denial of authorship would be to no avail: the report would be read as an “OECD report” even without its official stamp.Footnote 139 Consequently, “the conclusions and recommendations [and] even the language [had] to be seen in this light.”Footnote 140 What some readers would take as a mass of stylistic tangles and meaningless constructions in fact betrayed a preemptive defusing of the report’s reception through efforts made to reshape its presentation under duress.Footnote 141 The long meeting held at the OECD in January 1977 between the secretary-general and the new US vice president Walter Mondale, accompanied by the undersecretary of state for Economic Affairs and his assistant, Fred Bergsten—repeated in March of the same year in Washington—simply accentuated the enlistment of the OECD in the US strategy to convince the German and Japanese governments to partake in a joint expansion effort.Footnote 142 Though initially it had been necessary for the Secretariat to associate itself with the group, as the deadline approached every effort was made to create distance and thereby protect it from the fallout through a process of redrafting. This institutional anxiety reflects one of the fundamental contradictions of the OECD when it is held up as an “expert”: its role is to diagnose, innovate, and prescribe, but it works in fear of the main governments that support it, first and foremost the United States, without which its “expertise” might well be reduced to just one political stance among others.Footnote 143

During the 1970s, the issue of a “global demand regulation policy” was not reserved to the McCracken group. The volumes of Economic Outlook published by the OECD in 1976, a declaration by the European Council in favor of a concerted action plan in March 1977,Footnote 144 the preparatory documents for the OECD ministerial-level meeting of June 1977,Footnote 145 a tripartite report by the Brookings Institution published the same year (in which McCracken participated alongside Okun on behalf of the United States),Footnote 146 all pushed the United States, Japan, and Germany in the same direction: to act as the “locomotives” of the global economy through concerted recovery policies, in accordance with the wishes of the Carter administration. But this administration suffered a failure at the London G7 summit in May 1977 against German chancellor Helmut Schmidt and Japanese prime minister Takeo Fukuda.

Upon receipt of the McCracken report at the OECD’s “Ministerial” in June, the US secretary of the Treasury remained insistent: “We can succeed in achieving sustained non-inflationary growth … if both surplus and deficit countries allow exchange rates to play their appropriate role in the adjustment process.”Footnote 147 His statement at a press conference was understood in France and Germany as announcing an imminent devaluation of the dollar.Footnote 148 A further devaluation would have prompted the OPEC to raise the price of a barrel of oil and therefore intensify inflation at the global level, at a time when the United States was working to avert such an energy price hike. Following the example of the Nixon and Ford administrations, and despite its declarations in favor of human rights and international cooperation, the Carter administration secured the stability of US oil supplies and the purchase of US Treasury bonds with King Khalid bin Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia and the Shah of Iran (at least for a few more months).Footnote 149

US pressure on Japan in favor of expansionist policies continued in September 1977 at the IMF and in November at the EPC of the OECD. In December, Japan finally committed to 7% growth for 1978. The United States then turned its attention to Germany. Schmidt wished to hold a G7 summit in Bonn in July 1978, and Carter made his participation conditional upon specific commitments regarding growth and energy policy.Footnote 150 Although, for domestic tactical reasons, Schmidt was waiting for the summit to impose his policy of demand stimulation—especially in the face of the Bundesbank and his finance ministry—the deal was settled with the US government as early as April 1978: an agreement on a recovery package equivalent to 1% of German GDP. However the Bonn summit, like that held in London, did not address monetary questions—these were supposedly in the hands of the central banks, which were now more independent and compensated for this budgetary relaxation with monetary restriction.

In its final version, the McCracken report unsurprisingly declares itself “against going back to a formal pegging of exchange rates” and notes the “increased reliance on private lenders for official financing purposes.”Footnote 151 The limits to the creation of reserves for states were set more “by the private market’s judgment of the credit-worthiness of individual countries than by official multilateral evaluation of the policies being followed and the needs of the system as a whole. The international monetary system has taken on some of the characteristics of a domestic credit system without a central bank.” In this respect, the most worrying aspect was not “the increase in international liquidity as such” but “the extremely uneven accumulation of debt within and outside the OECD area.” However, no proposal was made to restrict, direct, or rebalance the activities of international capital markets, whose expansion was now almost limitless. On the contrary, it was stated that “compartmentalisation of financial markets should be reduced,” as should “institutional obstacles to the issue of indexed bonds” (government bonds included).Footnote 152 As Marris lamented, the report did not innovate in these areas and said “nothing at all on the institutional and practical aspects of international economic co-operation.”Footnote 153 One of the leading figures involved in the writing of the report was thus its first critic: nondecision in these circumstances equated to taking a real stand.

Following the US—and overall transpartisan—position, endorsed by the Jamaica Accords of January 1976 on floating exchange rates and the development of the financial industry, the McCracken report supported de facto a system of international monetary and financial coordination effected through the market, very different from Bretton Woods. No proposal was put forward based on Keynes’s or Robert Triffin’s notion of an international clearing union that would have a currency independent of states (the Bancor project)—an idea that remained inadmissible in the eyes of the US Congress.Footnote 154 Nor did it address James Tobin’s idea for a tax on short-term financial transactions (already evoked by Keynes in 1930)Footnote 155 to replace the capital controls that were now considered impracticable, especially after the British bond crisis of 1976.Footnote 156 There was no push toward a fiscal and monetary federalism on a regional scale in order to reduce the dependence of developing countries,Footnote 157 or of European countries against the dollar, as advocated in the MacDougall report issued in 1977 by the European Commission.Footnote 158 Also unmentioned was the Franco-German tandem with the European Monetary System after the Bonn summit in 1978, as well as the European Monetary Fund project, distinct from the IMF, attempted the same year by Schmidt before being withdrawn in the face of US opposition.Footnote 159 The dollar, ultimately, was never in competition.

The locomotive strategy produced the intended effects on the recovery of global demand but fed, entirely unintentionally, into the inflationary dynamics linked to the second oil crisis at the end of 1978. To bring down inflation in the United States, the new chairman of the FED (and Nixon’s former assistant secretary to the Treasury), Paul Volcker, appointed in the summer of 1979 by Carter, raised the reference rates from 11% to 20%, leading to a recession and the US unemployment rate rising to 10%. Inflation fell from almost 15% in 1980 to 3% in 1983. Ironically, this success in the fight against inflation at the expense of unemployment signaled, in a way, the continued relevance of the Phillips curve.