Louise's pictures

On 26 October 1877 the vicar general of the bishop of Tournai sent the following message to Fr Paul Niels of Bois-d'Haine, a small village in the Belgian province of Hainaut:

the act of taking Louise Lateau's photograph, an act that Mgr. the Bishop in no way authorised for the purpose of any kind of publicity whatsoever, but especially for the publicity in which you are, so we have been assured, very willing to engage, is diametrically opposed to the reserve that the Holy See imposes on itself and prescribes us on such occasions.Footnote 1

As a consequence, the note read, Niels was not to be surprised by the rigour of the measures that the bishop deemed fit to impose, ‘conform[ing to] the instructions of the Holy See’. Under threat of a suspension a divinis, Fr Niels was to send to the bishop all the pictures in his possession (as well as those that he had handed out) and ‘the negative plates of every kind, reproducing in one way or another the features of Louise Lateau’ within three days.Footnote 2 A similar demand was sent to the French priest, Charles Ducoulombier, a teacher at the Tourcoing College, who had assisted during the photoshoot. Ducoulombier was also forbidden to see Louise again or to say mass in Bois d'Haine.Footnote 3

Louise did not need any additional publicity to reach the public eye. In autumn 1877 she was already one of the best-known stigmatics of her time. Her case was fiercely discussed in public debates about medicine and religion, an object of ridicule for anti-Catholic liberals and a symbol of hope to Catholics, who felt comforted by her visible stigmata and interpreted them as a sign of God's presence on earth. So why did the bishop (who was convinced of her saintly character) resort to such stern measures regarding the photographs of a female stigmatic? This article will examine the events leading up to his ordinances in an attempt better to understand religious celebrities and the Catholic Church's attempts to control (and use) their fame.

Celebrity studies is a relatively young field, and apart from those scholars working on the sacralisation of celebrities, most research takes a rather secular perspective. The few scholars who have addressed the interaction between sanctity and celebrity have mainly done so by focusing on what happened after the demise of figures such as Thérèse of Lisieux or Padre Pio.Footnote 4 Furthermore, they have primarily focused on the twentieth century, as the era of the mass media, and adopted a top-down perspective, studying, for example, strategic canonisations or devotional-promotional practices.Footnote 5 The interaction between the lay public, the clergy and the ecclesiastical authorities concerning the creation of a public image and its use and misuse has rarely been studied. The ‘affair of the photographs’, as the episode came to be known, demonstrates how the publicisation of religious personalities was also under discussion in the second half of the nineteenth century, and shows that the impact of the medium was of central importance. This article will examine the ecclesiastical response to grassroots initiatives and trace what issues were at stake in October 1877.

The affair was as much about creating a public – saintly – image as it was about controlling it. Studying this case thus allows us to see how the new photographic techniques were being used to create a public image and document what contemporaries saw as sanctity. Photography was still at a rather early stage at the time but, as Thérèse Taylor has remarked, it had an important influence on contemporary ‘holy’ women: ‘The camera's ability to record reality and associated technological developments which led to the proliferation of commercial prints, created a new market for religious pictures. Photographic representation also promoted a fixation on appearances, and a reliance upon aesthetic standards, as an evidence of moral worth.’Footnote 6 In other words, as suggested by Claude Langlois, photography was a means of providing a portrait of the saint and demonstrating the sanctity of the figure.Footnote 7 Taking a photograph also implied the selection (of objects, poses and image, etc.) and, to a certain extent, manipulation of the photographed object better to serve the needs of those for whom it was intended.Footnote 8 The first point of relevance is therefore the aims of the Bois-d'Haine photographers – and this begins with an analysis of how the hands of Adeline Lateau (Louise's sister) were caught on camera.

Adeline's hands: staging sanctity

In order to understand the incentives for those involved in taking Louise's photographs, it is necessary to return to early October 1877. At that time Louise Lateau was already famous in Belgium and internationally. As the daughter of a railway worker (who had died soon after her birth), nothing destined her for the public eye until she started to display Christ's wounds in April 1868.Footnote 9 The ecstatic episodes that she experienced each Friday were well known: they were elaborately commented upon in newspaper articles and booklets, and the faithful could witness these episodes by visiting the house where she lived with her two sisters, Adeline and Rosine.Footnote 10 Rosine stubbornly protested against Louise's picture being taken, even after Marie and Pauline De Beukelaer had obtained permission from the bishop of Tournai, Edmond Dumont, on 15 February 1876.Footnote 11 Photographs of Louise were in high demand after the artist Alexandre Thomas had displayed a painting of her in spring 1876.Footnote 12 Rosine only agreed to the photography after intense persuasion and on condition that the photographer was a member of the clergy. Subsequently, a Jesuit, Ernest Lorleberg,Footnote 13 consented to participate in the undertaking, and on 3 October 1877 a small group travelled from Antwerp to Bois-d'Haine.

Three of the people involved wrote elaborate accounts of what happened over the following days. The diaries of Fr Niels, an exceptionally rich source of information about Louise's life, amply document the events in 1877. The photographer, Lorleberg, and Charles Ducoulombier also documented the episode. Most of these accounts seem to have been written after the bishop intervened, and they include descriptions, justifications of their actions and the correspondence (copied) between them and the vicar general of the diocese.Footnote 14 Apart from some minor references in biographies of Louise, these sources have never been thoroughly studied. This is even more remarkable given that they can be compared to the pictures which – against all odds – survived the episcopal intervention.

The reflections of these three male members of the clergy offer an insight into what they believed to be their mission in photographing the young stigmatic woman. Tellingly, three types of pictures were taken: portrait pictures of Louise (and her sisters), group photographs of the young women standing outside their house and pictures of Louise in ecstasy. In total, there were twenty-one negatives. While pictures of traditional saints had been circulating on devotional cards for centuries, in taking portrait photographs of a young girl who was assumed to have experienced supernatural phenomena, Lorleberg and his assistants were following a rather new trend.

More specifically, the events in Lourdes and its development as a highly commercialised location had encouraged the exploration of new photographic means for the promotion of the site and the cult. The young visionary Bernadette Soubirous had her picture taken in the 1860s to meet the demand of the Lourdes pilgrims. She was photographed in a studio, praying and re-enacting the Marian apparitions. As Claude Langlois has pointed out, in an attempt to increase the level of exoticism, Bernadette was photographed in the traditional dress of her region to enhance her appearance as an unspoiled young girl from the countryside.Footnote 15

Similar clues to Louise Lateau's humble background were also present in the images made of her: she wore a dress with an apron, her dressmaker's scissors were hanging from her belt and she wore small black fingerless gloves to cover the stigmata. Those who saw these pictures without knowing who the person was, were thereby given small clues (fingerless gloves, scissors) to uncover the identity of the stigmatised dressmaker. In this respect, the photograph echoes more traditional saintly iconography, in which saints are recognisable on the basis of an emblem. Similarly, the group pictures of Louise, her sisters and their pupil Egida had an idealising function and, as Ducoulombier explicitly noted, were intended to document the peaceful rural life that they led in their cottage.Footnote 16

Given the relative rarity of photographs at the time, Lorleberg was surprised at the ease with which Louise posed:

she does not seem to be nervous or impressionable like other persons of her sex. She poses without head support with the tranquillity of someone who has never done anything else. Anyone who remembers how impressed he was when his first portrait was taken will understand that this shows in Louise a calmness that one rarely finds, even among men.Footnote 17

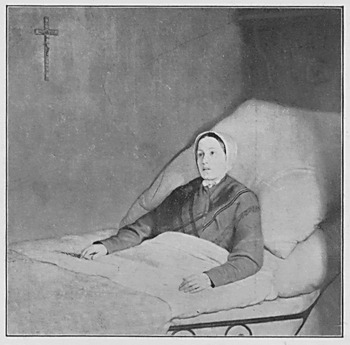

He liked best photograph no. 10 (see fig. 1), which showed Louise seated with her rosary and wearing fingerless gloves, praying while staring at a crucifix. According to Lorleberg, her figure was ‘transformed’ and the gaze, directed upwards, ‘illuminated’. He noted that while she was not in ecstasy when the photograph was taken, anyone who saw the picture might think that she was. In his opinion, this photograph best captured the saintly image of Louise.Footnote 18

Figure 1. Louise Lateau praying, October 1877 (photograph no. 10 in series taken by Ernest Lorleberg), ALL.

Unlike the Lourdes photographs, Louise's were not only portraits or studio re-enactments of the reported events. The Lorleberg group also photographed Louise in ecstasy and managed to do what, according to Fr Niels, had been impossible for painters to do because ‘the length of an ecstatic experience was too short and the expression of the figure changed too often for a painter to be able to capture her traits without recourse to photography’.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, a photographer faced similar problems. To generate a good effect, the person posing for a picture needed to keep still for some time (hence the head support). When Louise went through Christ's Passion or experienced other moments of ecstasy, she did not remain calm:

To capture her during the effusion of a powerful emotion was the test that naturally came to mind, but how could one catch a smile that formed and changed so easily on the lips of the ecstatic under the influence of the words that seemed to strike her and that she revealed through the expression on her face, or through various utterances…? It was a difficult task, but we tried it nonetheless by reciting the Hail Mary in a certain way; we thus managed to maintain the same smile and the same expression on Louise's face.Footnote 20

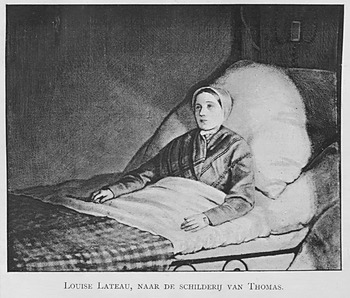

While the series of pictures create the impression of a genuine ‘capturing’ of Louise's ecstasy, they are not photographic ‘proof’ of a spontaneous event (which was the case with the Friday ecstasies).Footnote 21 The photographed episodes were induced and staged; for example, Louise's bed was pushed closer to the window and a second pillow was added. In addition, her sister Adeline held up a white sheet next to Louise's face better to illuminate the small room, which had limited direct light. As a result, her hands can be seen in one of the pictures (see fig. 2).Footnote 22 Lorleberg was initially kept in the dark about how the ecstasies were triggered (he was asked to leave the room), but Ducoulombier and Niels corresponded extensively on the matter afterwards. Prior experiments had shown that Louise's ecstasies could be provoked by bringing her a bottle of water used for ablution.Footnote 23 Ducoulombier later regretted taking the experiment a little too farFootnote 24 and remarked that he also hesitated at the time of the photoshoot: ‘Could I, even in the interest of the work that we were executing, provoke an unaccustomed ecstasy and rapture? Did respect for saintly things not oblige me to abstain?’Footnote 25 Against all expectations, the ecstasy pictures were successful. Ducoulombier believed that there was

no earthly representation of the divine dénouement of the drama of the Passion that is more moving and more accurate [see fig. 3]. The Christian eye will be able to study in it the agony with all its anguish and the image of death with all the sorrows that accompany it. From that perspective, the photograph will become a sermon that will make saintly souls’ tears flow and provide an idea of the torments that our Lord endured for us on the Cross.Footnote 26

This idealisation of Louise's suffering might sound strange to present-day ears. For nineteenth-century Catholics, however, the beauty of pain and its productive, reparatory nature were well known. Through physical and emotional suffering, Louise was a ‘victim soul’, repenting for the sins of others and society as a whole. Thus, even in her moments of greatest pain – when she suffered through Christ's Passion on Fridays – she was the embodiment of a Christian ideal, a saint in the making.Footnote 27 To those involved, the importance of the photographs could hardly be overestimated: ‘Never has photography, which is like God's pen, written such a poem. The imagination of Christian artists has of course been able to conceive an ecstatic ideal, and show on their canvas the splendour of the divine rays that flow freely on the human face during ecstasy.’ They were preserving for the following generations ‘the marvellous but mobile illuminations of a transfigured face’ without ‘recourse to imagination’ and ‘on paper that does not deceive or invent anything’.Footnote 28 In fact, this set of photographs showed Louise as a prototypical mystic of her time. Nicole Priesching has demonstrated that in the nineteenth century it was primarily the corporeal aspects of the religious experience, rather than the intellectual content, that led these ‘ecstatic women’ to be regarded as mystics.Footnote 29

Figure 2. Louise Lateau in bed with her rosary; Adeline's hands can be seen on the right, October 1877 (photograph no. 11, Lorleberg), ALL.

Figure 3. Louise Lateau in ecstasy, October 1877 (photograph no. 23, Lorleberg), ALL.

The photographic plates still needed some work, but, as the small group packed up, they considered that they had succeeded in documenting Louise's case and in taking the first photograph of someone in religious ecstasy.Footnote 30 Lorleberg, however, admitted in his diary that he liked Louise better in her ‘natural state’. He had felt ill at ease when he first saw Louise in ecstasy as it was strange to see her act ‘like an automaton’, in a manner ‘reminiscent of a nervous illness’. He was none the less full of praise for the humble composure of the girl: ‘Veneration, thus, I told myself, for natural Louise’.Footnote 31 To understand Lorleberg's unease, it has to be recognised that these photographs could be read in a way that suggests hysteria rather than sanctity. More specifically, the poses of the Crucifixion and the Passion had been linked to fits of hysteria by the scholars of La Salpêtrière in Paris. Louise Lateau had already been associated with hysteria several times, with one of the most vehement attacks published only two years earlier, in 1875, by the French neurologist Désiré Bourneville. The third chapter of his book, Louise Lateau; ou, La stigmatisée belge, stated, for example, that ‘Louise Lateau is a hysteric: a clinical demonstration.’Footnote 32 A year later, with Paul Regnard, he published the first volume of the Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière, capturing the various moments of a hysterical fit in photographs and alluding to the case of Louise Lateau when explaining some of the poses (such as the Crucifixion pose). Bourneville, Regnard and Charcot used photography to experiment, catalogue and educate, and they were also using new photographic means to pathologise the ‘new mystics’.Footnote 33 It seems that even in Belgium, where Louise had been the object of two medical examinations (in 1868–9 and 1874–5) – which had not come to any conclusions but had been openly commented upon in the press none the less – such associations were not easily ignored.Footnote 34 Every picture of Louise in a pose similar to one that the doctors of La Salpêtrière had defined as a state of hysteria made her vulnerable to such accusations. However, for the bishop of Tournai, it was the idea that they served to create publicity that was the major reason for his stern response.

‘Premature and untimely’: the bishop's response

On the other hand, you seem to have believed, Mgr., that I intended to publish and distribute the portrait of Louise. I can affirm once more, in the sincerity of my conscience, that this thought never entered my mind.Footnote 35

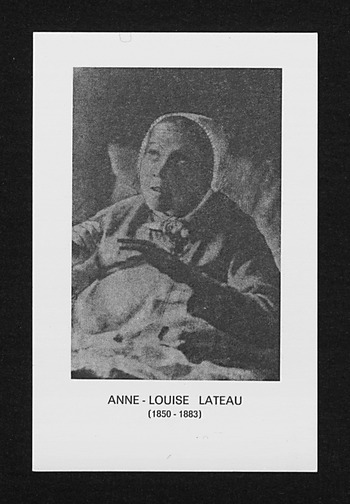

From the first appearance of the stigmata on Louise's body, on 24 April 1868, the Belgian bishops had adopted an attitude of reserve. Nevertheless, they had not stopped frequent visits by the public and even went to Bois-d'Haine to see for themselves.Footnote 36 The bishop of Tournai had also commissioned a painting of her in 1876 by Alexandre Thomas, which showed the young girl in a state of calm, contemplating the crucifix, with little trace of the stigmata (see fig. 4). This seems to have been a deliberate choice, as the Brussels artist had also produced a smaller portrait of Louise in ecstasy with bloody traces of the head wound visible and with Louise's mouth slightly open (see fig. 5). Given the fact that Niels had mentioned the immediacy of photography as necessary to capture Louise's features during ecstasy, it is interesting to note that Alexandre Thomas had indeed succeeded in painting her in that condition, but had not used that image for his official painting.Footnote 37 Thomas knew that whenever relics were brought close to Louise, her features contracted, and the painter preferred not to depict her in such a condition.Footnote 38 The sober and calm setting of the portrait of the ‘holy girl’ (‘sainte fille’) seems to have been appreciated by the public as well. Thomas was believed to have painted the ‘heavenly face’Footnote 39 wonderfully and the ‘angelic figure of she whom one might in future invoke as a saint’.Footnote 40

Figure 4. Postcard of a painting of Louise Lateau by Alexandre Thomas, April 1876, Ruusbroec Institute, Antwerp, RG-PC Angels/saints/blessed souls: Lateau 1.

Figure 5. Print of a smaller painting of Louise Lateau by Alexandre Thomas: Almanach National Belge Notre Dame de Lourdes, Louvain 1914, 53.

How can the bishop's commissioning of a painting of Louise Lateau, as well as his granting permission for the photoshoot, be reconciled with his response to the photographs? From his first response to Fr Niels onwards, there are references to the Holy See demanding the retraction, with the bishop of Tournai only echoing their demand.Footnote 41 Rome was always very careful in these matters and wanted to deflect from these exceptional souls anything that ‘might obscure divine action or be open to malicious interpretations’.Footnote 42 As Dumont noted, ‘Everything was premature and untimely’.Footnote 43 What happened in Louise's case was in fact similar to the measures taken in 1924 by the head of the cloister of San Giovanni Rotondo in the case of Padre Pio (1887–1968). He forbade pictures being made of the Italian stigmatic in order to avoid the accusation of the commercialisation of the cult.Footnote 44

Thus, there was an immense difference between a painting that could be kept safely behind the closed doors of the episcopal palace and photographic negatives which could be reproduced endlessly, were difficult to monitor and easy to exploit. Apparently, the whole painting commission had been simply an attempt to hinder the plans of Cardinal Dechamps to have a portrait made and thereby to avoid any misuse of such a painting by others.Footnote 45 Canon A. Thiéry cites the following explanatory note that Dumont published in La Vérité on 25 June 1880:

The cardinal [Dechamps] has always been one of the great admirers of Louise Lateau. He even wanted the portrait of Louise Lateau to be made despite her wishes. So, to avoid the portrait of this girl being exhibited, I was obliged to have it painted myself by the painter Thomas. I have always kept it hidden, even though I paid 4000 fr. for it. I have never published a line about Louise Lateau and I have ordered the priest to suppress the photographs of Louise.Footnote 46

That Dumont had permitted the photographs was conveniently omitted. In Thiery's biography, it is primarily Dechamps who seems to have been eager to promote Louise and who convinced Alexandre Thomas to put his painting of Louise on display in his studio on the Rue du Commerce in Brussels. Apparently, numerous people came to see the painting even before Thomas handed it over to the bishop of Tournai.Footnote 47 Interestingly, Marie and Pauline De Beukelaer also had the painting photographed (by a photographer named Boisson) even before it left Bois-d'Haine. Their letters document how careful they were not to allow the negatives out of their sight – only two prints were to be made: one for the bishop and one for Niels.Footnote 48 In fact, some photographs connected to Louise had already been sold for profit in Bois-d'Haine. These featured the church of Bois-d'Haine and the house of the Lateau sisters. What seems to have been particularly distressing for Dumont is that they were sold by the ‘vendor of the bad newspapers’ (‘crieur des mauvais journaux’).Footnote 49

Admittedly, Thiéry paints a rather black-and-white picture of the cardinal and the bishop of Tournai, but it is clear that the bishop accused Lorleberg and the others of exploitation and unwanted publicity. When Ducoulombier attempted to explain the bishop's reasons for banning him from Bois-d'Haine, he stated that he believed that Bishop Dumont had an idée fixe ‘that we wanted to exploit photography and put a print to one side to use according to our needs’.Footnote 50 Pleading his friend's case, Fr Niels wrote to the bishop several times, and while he agreed that they had indeed taken a lot of photographs of Louise, he noted that they had only done so because they did not know whether they were going to be successful. He claimed that they had never intended to exploit them and while he had indeed sent photographs to Ducoulombier this was only a temporary loan, to enable him to finish his report on the photoshoot.Footnote 51

However, a letter of 25 October 1877 from the Jesuit Provincial, Joseph Janssens (Lorleberg's superior), to Bishop Dumont hints at something slightly different. Janssens describes how Lorleberg had gone to Bois-d'Haine a few days before with the photographs of Louise Lateau and was planning to travel to Tournai to deliver them to the bishop. Fr Niels, however, convinced him not to go because the bishop was on his way to Rome and took delivery of the photographs himself:

Since then he has asked for new copies for benefactors. As I think that one has to be very cautious in this affair, I told Father Lorleberg to go to Tournai as soon as possible, to talk to your Highness, and offer him the photographs. If your Highness cannot receive him tomorrow, perhaps he would be so kind as to ask one of the Vicar Generals to do so. The pastor of Bois-d'Haine might keep a copy, but I fear that the photographs might be circulated and exploited.Footnote 52

Bishop Dumont acted accordingly. But why did he allow the photoshoot to take place in the first place?Footnote 53 The primary reason seems to have been that it was in order to document the case. On 7 April 1876, during Alexandre Thomas's painting sessions, Fr Niels expressed his trust in the good outcome of the painting, but signalled to the bishop the aspects that they were missing out on: ‘The portrait of Louise will be well done, but it will be a great loss not to have her portrait whilst in ecstasy. For this, one would absolutely need to use photography.’Footnote 54 He did not seem to be aware of the permission that the bishop had already granted to Marie and Pauline De Beukelaer in February 1876. His letter, however, illustrates the documentary intention of the photographs – this reason was repeatedly emphasised by Niels and his colleagues in their apologetic reports. Niels only wanted one print of each negative to be kept in the parish archives to document the case for future generationsFootnote 55 and opened his report on the photographs with the following note: ‘the religious authorities wanted for some time to capture with photography the features of Louise Lateau, so often transfigured by ecstasy, and capture forever her expression during the incomparable scenes on Fridays’.Footnote 56

Louise's image

Lorleberg and Ducoulombier considered their photographic mission to have been a success, because God, ‘the divine photographer’, had helped them by sending them the right lighting conditions.Footnote 57 They had succeeded in taking advantage of rapidly evolving photographic techniques to capture Louise in ecstasy, and they lauded the beauty of these moments. Nevertheless, a certain unease seems to have lingered, with Lorleberg explicitly stating his preference for the photographs of Louise in a natural state. A similar preference is to be found in the work of Alexandre Thomas, whose painting depicts Louise in a calm, contemplative state, although he had also managed to paint a smaller picture of her in ecstasy. It is interesting to note that even this painting would be ‘toned’ down. In a drawing based on Thomas's painting, which was published in 1891 in a book on Louise and other stigmatics, the slightly open mouth in the original is no longer open at all (see fig. 6).Footnote 58

Figure 6. Drawing based on the larger painting by Alexandre Thomas: Riko, Louise Lateau en andere mystieken, frontispiece.

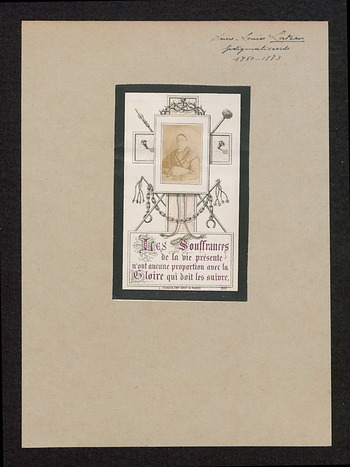

Louise's image was indeed distributed despite all attempts at control. It is unclear when and by what means it began to be circulated, but as early as 1885 (two years after her death), a portrait based on Thomas's painting was included in Souvenirs de Bois d'Haine. Variations on the painting can also be found on devotional cards in honour of Louise Lateau (notoriously difficult to date). Moreover, even the portrait pictures, and particularly the one that Lorleberg thought best captured Louise's saintly character, can be found on devotional cards (see fig 7). Thus, the pictures that eventually made it into the public realm were just like the photographs of Bernadette, each one ‘a safe and controllable image’.Footnote 59 In fact, those involved in the 1877 affair seem only to have distributed the ‘natural’ photographs among their friends.Footnote 60

Figure 7. Devotional card of Louise Lateau, Ruusbroec Institute.

The image that these devotional cards and book illustrations create of Louise is thus a slightly ‘filtered’ version. Her stigmata are barely present, or covered by fingerless gloves. The effect is an image of controlled, calm prayer, rather than uncontrolled and uncontrollable ecstasy. The limited importance attached to the stigmata in these pictures was in line with the Vatican stance on stigmata. Considered to be epiphenomena, they were never in themselves sufficient reason to be declared a saint. On the contrary, they made stigmatics vulnerable to accusations of hysteria and fraud, as the status of these phenomena was no longer considered incontestable by the Church.Footnote 61 Nevertheless, such sober visual representations cannot be considered the dominant or only style of representation of stigmatics. If Louise's pictures are compared with with those of two other, younger, Belgian lay stigmatics – Rosalie Put (1868–1919) and Clara Jung (1887–1952) – it is clear that their bloody images were distributed widely and seemed to function as a kind of additional confirmation of the truth of their stories. In Clara Jung's case, one of her devotional cards features the stigmatic with her face covered in blood, while pictures of Rosalie Put reproduced in German and Dutch texts show her in ecstasy, with a blood-smeared face and clutching her rosary. Similar, bloody images of older stigmatics were also circulated.Footnote 62

The devotional cards featuring Louise Lateau offer a particular set of sources in this regard. One of the oldest cards features an image based on Thomas's painting, thus, a rather sober style of representation. The picture is, however, positioned at the centre of a crucifix, surrounded by the instruments of torture that cause the stigmata, and is thus a clear reference to the latter. Similarly, a devotional card depicting Louise – with an imprimatur of 1938 and a plea to contact the pastor of Bois-d'Haine should a favour be obtained through the mediation of Louise – included Lorleberg's ‘saintly’ image.Footnote 63 On the back, however, one of the first lines states that Louise was stigmatised. Thus, while the stigmata seem to have been regarded as of little consequence at the Vatican level, they were certainly of central importance in the initial promotion of the cult. In the case of Louise, hints about the wounds were linked to an aestheticised, incontestable image of Louise.

The ecstasy pictures and smaller painting seem to have been lost from view for some time, until an article featuring them was published in the Almanach National Belge Notre Dame de Lourdes in 1914, with the title ‘Unpublished portraits of Louise Lateau’. The introduction to the article claims that while the portrait commissioned by the bishop(s) was well known, Alexandre Thomas had also created a smaller portrait ‘for his own edification’ (see fig. 5). The Almanach included a painting which was unpublished at the time, in which Louise displayed the wounds originally inflicted upon Christ by the crown of thorns. Lorleberg's ecstasy pictures also featured extensively and the readers were guided on how to understand them: ‘Her [Louise's] expression is earnest and pained, her arms are extended by compassion like those of someone who is crucified. One can observe in all her features the deepest consternation and the pity that faithfully shares in the pains of the crucified.’Footnote 64 Interestingly, the pictures of Louise in ecstasy feature on some even later devotional cards (with an imprimatur of 1938 and 1974, but probably printed more recently: see fig. 8).

Figure 8. Devotional card of Louise Lateau, Ruusbroec Institute.

Did the episcopal authorities of the Tournai diocese develop a more positive stance towards Louise after her death? Is that why such cards can now be traced? In reality, a positive evaluation had already begun during her lifetime. Even Bishop Dumont was convinced of her saintly character – at least that is what Ducoulombier reports. The Tourcoing priest did not give up visiting Louise without protest, and in late February 1878 he went to see Dumont. The visit was not very successful as Ducoulombier only obtained permission to photograph Louise after her death. In a letter to Niels, he notes that the bishop was very kind, and that the ‘Monseigneur is full of admiration for Louise and regards her as a saint. He will take care after her death of everything that the law prescribes on such an occasion.’Footnote 65 By the time that Louise died, however, the situation had changed completely, with Bishop Dumont removed from his position and forbidden from seeing Louise (or ‘counselled’ not to do so).Footnote 66 Dumont was actively involved in the School War which was being waged throughout Belgium at the time (1878–84), creating numerous religious schools.

At this point, tensions between ultramontane and liberal Catholics were also on the rise as well. While Cardinal Dechamps had good connections with the liberal Catholics but did not oppose ultramontane actions as actively as his predecessor had done, Dumont became an eager promotor of the ultramontane faction.Footnote 67 His combative stance and nervous disposition eventually led Pope Leo xiii to intervene and retract Dumont's jurisdiction in November 1879 and his title in 1880. Any hint of an understanding between Louise and Dumont could taint her reputation, as could her alleged disobedience to the new bishop, Isidore-Joseph Du Rousseaux. In 1905 a ‘mémoire justicatif’ was published by Niels, which reiterated that the public assaults on Louise's person arose because of her ties with Dumont.Footnote 68 Thus, by a strange turn of events, the bishop who had once banned others from visiting Louise and claimed that this was to protect her reputation, was now himself banned and a danger to her reputation. However, both his active interference in the photography episode and the later discussions of his continuing visits to Louise reveal that the reputation and public image of a stigmatic were carefully monitored. The people involved in this particular affair did not underestimate the importance of an untainted, carefully constructed and monitored image. For there to be any chance of them aspiring to more, the ‘saint-to-be’ would have to leave this world with an untarnished reputation.

Sanctity in the making

Both Dumont and Dechamps thus appear to have had faith in events in Bois-d'Haine, despite Dumont's actions seeming to suggest the opposite. In a period in which the tensions among liberals and Catholics were rising and in which one would have expected him to support popular religious dynamism, Dumont intervened in a case that, for many, was physical proof of God's presence in the world, a symbol of hope to Catholics (of all nationalities, who felt oppressed. Interestingly, Dumont interfered precisely because he believed in Louise Lateau and did not want to diminish her chances of beatification, if not canonisation, after her death. Impeding the circulation of her portrait (and any profit that might be made out of it) countered all accusations of commercialism and publicity that might jeopardise Louise's case in the future. At the same time, however, posthumous official recognition could only occur if people knew about Louise and if her case was well documented. Visits to her house were not therefore prevented, Thomas was given the commission to paint her, and the photoshoot was authorised to provide visual proof of the ecstatic episodes that painters had difficulty depicting. The pictures provided documentary ‘proof’ of Louise's ecstasy – albeit staged – visualising the exceptional corporeal phenomena as the basis for Louise's claim to mystical powers and even sanctity. Nevertheless, while Lorleberg and Ducoulombier succeeded in taking what they believed to be the first pictures of someone in ecstasy, it is telling that these were not the pictures that Niels and his friends decided to circulate among their friends. Only the portraits showing Louise in a calm state were used to promote her image. This distribution of the pictures, however – albeit on a limited scale – alarmed the ecclesiastical authorities. Whatever possibilities photography created, it also had a downside, as it was a medium that was difficult to control: several copies of one photograph could be produced without much effort or cost. Thus, half a century before Padre Pio's photographs were banned, Louise's pictures were recalled and most were destroyed. Luckily, however, that intervention was not a complete success and the images survived.