Aims

The subject of this article is the role of freehold land and property in the developing commercial economy of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. As we will detail, in many circumstances, property in medieval England could be bought and sold as a means of accruing profit. During our research we have created the largest data set of English property buyers and sellers to date, detailing close to 100,000 records. By analyzing the data and identifying trends, we will argue that this type of commercial activity signals the beginning of the development of property as an asset class. Speculation enabled “medieval investors” the ability to “profit” both in terms of the social advancement that landownership bestowed and from the economic value of the real estate equity and rental incomes. We further highlight this dynamic through a number of case studies of some prominent investors identified from the data set. These investors made group purchases, were involved in multiple transactions, and bought land in areas outside their own local influence.

The study is divided into two sections. In the first, we examine the social background of the individuals involved in this market and how this changed over time. In the second, we attempt to examine the motivations of the individuals involved in freehold property transactions for evidence of investment activity. To date, analysis of medieval property investment has been based largely on case studies, which, though useful, are limited in their ability to quantify the extent and overall character of this phenomenon; furthermore, many existing studies have focused on property investment by ecclesiastical institutions rather than individuals.Footnote 1 This is in part due to the difficulty inherent in attributing motives to buyers; it is problematic to label someone an “investor” without detailed investigation of his or her transaction history and business practices on a case-by-case basis. We attempt to tackle this problem by defining some key characteristics of an investment transaction. We use a broad definition of investment, signified by purchase for means of profit rather than consumption. Evidence for property investment is taken from three main indicators: (1) the buyer has purchased property as part of a group, suggesting the existence of business partnerships or syndicates; (2) the buyer engages in multiple transactions within a relatively short period of time; and (3) there is a significant distance between the regional origins of the buyer or seller (as stated in the source) and the location of the property. We will argue that an increasing number of transactions of this type took place over the course of the fifteenth century, in line with the growing commercialization of the English property market.

Background

Until the late 1980s, the predominant view of the medieval English economy was one characterized by a reliance on subsistence agriculture, featuring minimal technological innovation and relatively little commercial activity. The onset of the Black Death in the mid-fourteenth century was thought to have caused a further decline in productivity, leading to large-scale depression in the fifteenth century.Footnote 2 However, in the last three decades, there has been a shift away from this view, with increasing emphasis on the commercial character of the medieval economy in both the period preceding the plague and its aftermath. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the population doubled, leading to innovations in farming techniques, increasing urbanization, and the development of a system of regional markets.Footnote 3 This allowed for greater regional specialization in industry, an increase in the use of currency, and the development of credit systems.Footnote 4 While the sharp decline in population following the Black Death caused a substantial drop in economic productivity, it appears that the existing commercial infrastructure survived more or less intact.Footnote 5 Indeed, it is thought that the widespread social changes resulting from the plague made an important contribution to the process of commercialization. The most significant change in this respect was the collapse of the bonded system of labor known as feudalism, as the decrease in population led to labor shortages, in turn resulting in increased wages, reduced rents, and greater social and geographic mobility.Footnote 6 In addition, these demographic changes precipitated important shifts in patterns of production and consumption; decline in demand for grain resulted in a movement from arable to pastoral farming and improvements occurred in the standard of living.Footnote 7

The concept of property ownership in medieval England differed substantially from that of the present day. Under the feudal system, the transfer of customary land was strictly regulated; property could only be transferred from one individual to another after it had reverted to the lord of the manor on which it was held, who would pass it on to an appointed heir in return for a fee. Despite the innovations taking place in other areas of the medieval economy, we might therefore assume that the property market was relatively static, with most transfers taking place at long intervals between family members, and offering little opportunity for speculative investment. However, by the beginning of the fourteenth century, approximately 50 percent of land was freehold, meaning that it could be conveyed without the involvement of the lord by means of private deeds drawn up by lawyers.Footnote 8 The basis for this market in freehold land lay in the series of legislation passed by Henry II in the twelfth century known as the common law, which allowed for the legal protection of the title to property in the royal courts.Footnote 9

Evidence suggests that in the beginning of the fourteenth century, landownership was dominated by a comparatively small minority; while the total population stood at just over 4 million people, a group of approximately 1000 powerful landowners (comprising the king, the higher nobility and clergy, and large religious institutions) accounted for about half of the total income from landownership.Footnote 10 However, already by this period the number of freeholders had increased to such a degree that they outnumbered those of servile status, meaning that a high number of people were active in the freehold land market at the lower level.Footnote 11 Evidence from the Hundred Rolls of 1279 suggests that freeholders came from a variety of social backgrounds, including lower gentry, clerics, merchants, and craftsmen.Footnote 12 The attraction of freehold land lay in its ability to confer social status on the holder, and also in the security it afforded in supplying a source of food or income. Medieval historians have in the past acknowledged the importance of property accumulation as a secure means of storing capital,Footnote 13 but it is only relatively recently that studies of the period have emphasized the potential of property purchase to be a profit-making venture.Footnote 14 This has contributed to a growing literature that stresses the role of market forces in the transfer of land and property in England during the later medieval period.Footnote 15

Sources and Database

Previous studies of the medieval land market have made use of such sources as deeds, private charters, and rent rolls.Footnote 16 However, while these sources are useful for the study of specific urban or rural areas, they are scattered across different archives, which limits their potential for the analysis of large-scale market activity. For this reason, our study is based on data collected from the Feet of Fines (for an example of one of these documents, see Appendix). Fines (also known as final concords) are copies of agreements made in the Court of Common Pleas recording the outcome of legal disputes over freehold property. By the end of the thirteenth century, these disputes are acknowledged to have been largely fictitious, and fines had become, in the words of one of their editors, “a convenient and secure means of conveying freehold estates.”Footnote 17 The original document was tripartite; the fine was copied three times onto a single sheet of parchment, and the upper two sections were given to the parties involved, while the “foot” of the fine was kept as a record by the court. There are tens of thousands of these documents in the National Archives (hereafter TNA), covering the period between 1195 and 1509 and describing properties from all over the country.Footnote 18 A number of calendars and editions have been published since the nineteenth century. As legal documents, fines are formulaic, recording:

- the dateFootnote 19

- the terms of the transfer

- the location and description of the property and its assets

- the names (and sometimes regional origins and social status) of the querent (the plaintiff, i.e., the purchaser) and the deforciant (the defendant, i.e., the seller)

- the consideration, a sum of money given in return for the title to the property

A database has been constructed containing information extracted from nearly 25,000 fines dating from the period 1300–1508. In addition to data from the counties of Essex and Warwickshire obtained from Yates, Campbell, and Casson, this database includes new data from the counties of Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Devon, Hampshire, Hertfordshire, Herefordshire, Kent, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, London and Middlesex, Northamptonshire, Northumberland, Nottinghamshire, Oxfordshire, Rutland, Shropshire, Worcestershire, and Yorkshire.Footnote 20 These counties were selected on the basis of accessibility to sources and in order to provide a comparison between predominantly rural areas and those in proximity to urban centers and areas of higher population. In particular, we wished to examine the extent to which property investment was affected by proximity to London. The coverage of the data set is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Data summary

a Percentage population figures for the year 1377 taken from table 8A in Broadberry, Campbell, and van Leeuwen, “English Medieval Population: Reconciling Time Series and Cross-Sectional Evidence.”

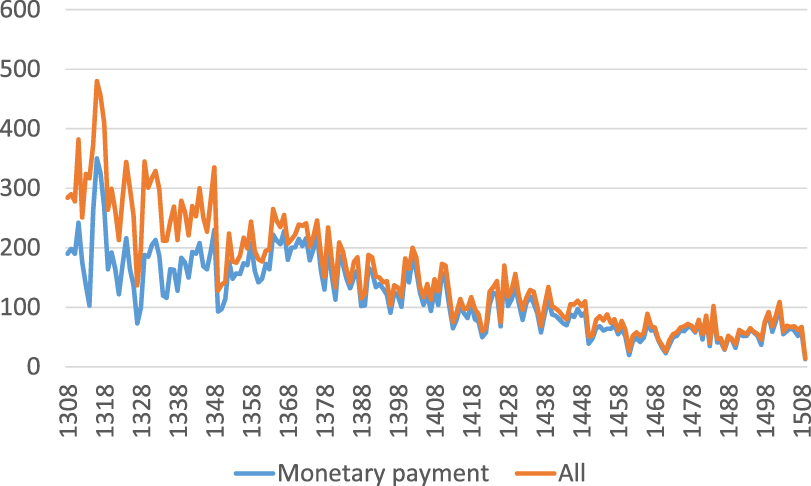

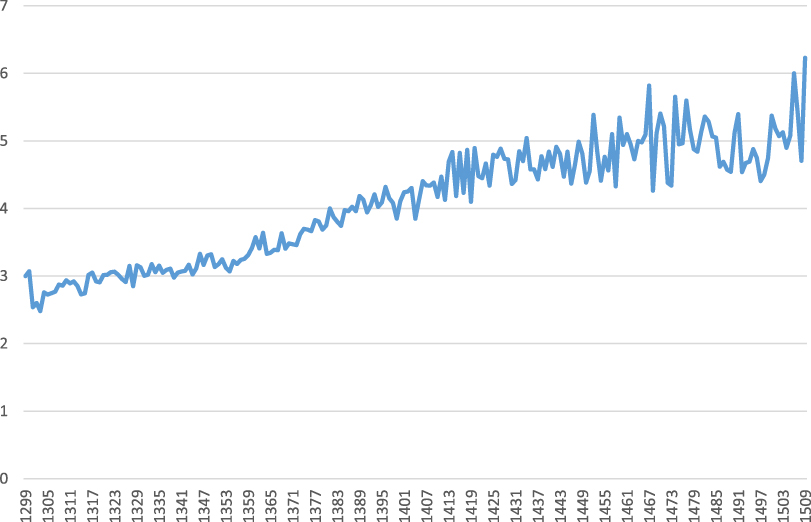

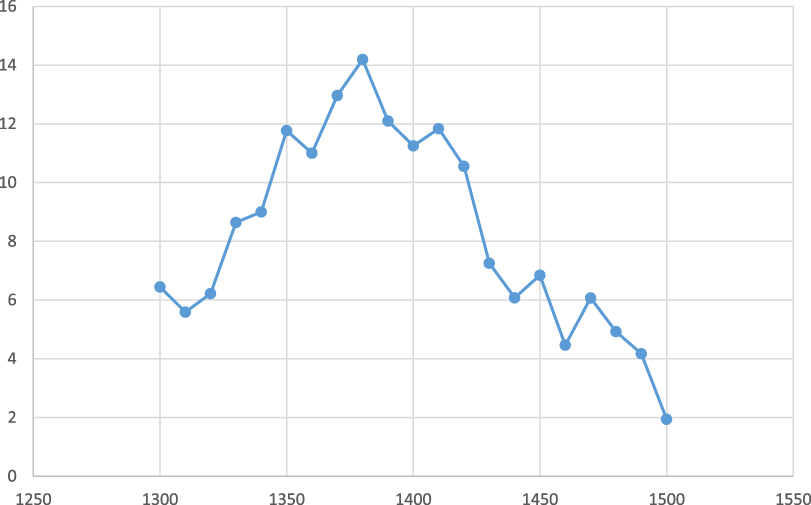

Fines have only recently begun to be used as a source for analysis of the medieval property market, as historians have for a long time viewed them as problematic. The formulaic nature of the document means that it is sometimes difficult to tell exactly what kind of transaction was taking place. Several different types of legal action were recorded as fines; whereas some fines might be viewed as straightforward property sales, others record the process of inheritance or other types of feudal arrangement. For this reason, certain types of fine were omitted when collecting data for this study. These include fines that either record no monetary consideration or the payment of a symbolic item such as a rose, a sparrowhawk, or a pair of gloves. These documents are assumed to more often represent actions such as entails, life tenancies, or the alienation of land in mortmain, and thus to represent either feudal or intrafamilial transactions that are less representative of commercial activity. This assumption is supported by the fact that the number of nonmonetary fines declines over time; they are relatively numerous in the period before 1350, but by the late fourteenth century there are only a few transactions of this type per year (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Number of fines per year compared with monetary payments only, 1308–1508.

Recent studies based on fines have found a gradual decrease in market activity over the period, accompanied by an increase in the size of the properties transacted.Footnote 21 Bell, Brooks, and Killick have found that this decline was offset by peaks in market activity following periods of crisis, specifically, the Great Famine of 1315–1322 and the Black Death of the mid-fourteenth century. They argue that this was the result of dynamic changes in the social basis for property ownership, which allowed for the liberalization of the market to commercial interests. In terms of regional variation, the total number of transactions in each county over the period is demonstrated to broadly correspond to the size and population of that county; however, they also argue that this varied according to proximity to commercial centers. The counties surrounding London are regions of high market activity, as they were frequent sites of investment for buyers from the capital.Footnote 22 In this current paper, we attempt to build on these results by examining in detail the landholders in the fines to determine how changes in their social composition contributed to the overall picture of freehold property market activity.

Social Background of the Buyers and Sellers

The database contains 92,652 records relating to buyers and sellers involved in the fines (Table 2). In addition to the information contained within the documents themselves, the database also contains a number of standardized fields in which these individuals are categorized according to type, permitting detailed analysis of regional and temporal trends. The information given varies from person to person; in most cases, it is limited to first and second name, role in the transaction, and where applicable, relationship to the other parties (e.g., “wife/son of …”). Information on gender has been assigned on the basis of the first name and from familial relationships or other contextual information. Relationships between buyers and sellers, unless explicitly stated, have been inferred on the basis of possession of a shared surname. In approximately 27 percent of cases, information is given in the sources regarding the regional origins of the individuals participating in the transactions; for example, “William Broun of Bedford.”Footnote 23 In the database, wives and children have been assigned the same regional origins as their husbands or parents. A surname is not assumed to be evidence of regional origin unless it is identical to the location of the property involved in the transaction. An additional field has been included to denote the distance of the buyer or seller from the property location; this will be discussed in more detail in the section “Distance Between Buyer and Property.” In some cases further information is given regarding the person’s status (e.g., “Knight”) or occupation (e.g., “Merchant”). This information has been categorized in the database according to nine groups: Agriculture; Clergy; Craftsman; Gentry; Merchant; Nobility; Legal/Administrative; Service; and Other.

Table 2 Overview of person records

Table 2 demonstrates that, while the number of records is evenly divided into buyers and sellers, there is a clear gender imbalance within the records; more than 70 percent of the litigants are male, reflecting the differing legal positions of men and women regarding property ownership during this period. Under the system of primogeniture, all property was inherited by the eldest male heir; if there were no male heirs, it was divided equally among the daughters. Upon marriage, a woman’s property interests (which may have been inherited or acquired through her dowry) were transferred to her husband. However, he required her consent to sell these properties, and if he died, she was entitled to a life interest in one-third of his lands, which she retained in the event of any subsequent remarriage.Footnote 24 Fines were the only means by which a married woman’s property could be conveyed.Footnote 25 This is reflected in our data; in more than 80 percent of recorded instances of women in the fines, they were selling property rather than buying it. In the majority of cases, women were involved in transacting property with their husbands, but there are a number of instances in which unmarried women were involved in property sales, either alone or in partnership with relatives or unrelated parties. There are 251 records in which a female litigant is described as a widow, in more than half of which she is the purchaser, indicating that widows were on average far more active in acquiring property than married women. In many instances a woman’s married status is unclear in the records; with the exception of widows, unmarried status is only explicitly stated in one case in 1488, in which “Elena Rolff, ‘syngelwoman’, the daughter-heir of Thomas Rolff and Elena his wife” sold two messuages and two gardens in Windsor, Berkshire, for the sum of £30.Footnote 26 Evidence has indicated that participation of women in the land market decreased over the course of the medieval period due to increasing commercialization and the tendency to give dowries in the form of cash or goods rather than property.Footnote 27 This is supported by our data; as Table 3 demonstrates, women make up approximately one-third of litigants during the fourteenth century, falling to less than a quarter in the first half of the fifteenth century.

Table 3 Person records over time

Given the fact that the status and regional origins of litigants are only present in some cases in these sources, it is necessary to examine patterns in the frequency of recording this information before any conclusions can be drawn (Tables 2 and 3). Information on the regional origin of a litigant is more often given in records dating from the fourteenth century (in just over a third of cases), whereas in the fifteenth century it appears in only 10 percent of the fines. Conversely, information regarding status appears to be more frequently recorded over time; it appears in only 7 percent of transactions taking place before 1350, rising to almost 20 percent in the second half of the fifteenth century. This may be interpreted within the context of the rising geographical mobility of the population, meaning that place of origin was a less secure means of identification, and also the increasing division of labor and proliferation of new occupations, with the result that a growing number of people were defined by their occupational status.Footnote 28 Status information is more frequently recorded for buyers than sellers; the likeliest explanation for this is that buyers had a greater incentive to include personal information and thus make explicit their identities, as they might need to prove their claims to the property in the future.

Given that the number of fines recording information regarding the status of the litigant is relatively low, what assumptions can we make regarding those individuals for whom no information is recorded beyond their names? We could interpret a lack of information regarding an individual as denoting low status; the increase in personal information in the sources post-1350 could therefore be interpreted not as the result of a change in recording practices but as indicative of a change in the social makeup of litigants. However, closer analysis reveals inconsistencies in the way individuals were described in the fines, prompting caution in making this interpretation. In some cases, we can identify litigants whom we know through other sources to be of relatively high status, but for whom little distinguishing information is recorded in the fines themselves; for instance, Hugh Oldham, who held many ecclesiastical offices from the 1490s onward and was appointed bishop of Exeter in 1504, appears on numerous occasions in the fines described simply as “Hugh Oldom, clerk.”Footnote 29 The same individual, occurring in multiple transactions, might be described in different ways; for example, Sir John Shaa, a prominent goldsmith and Lord Mayor of London in 1501, is sometimes described in the fines as “John Shaa, knight,” sometimes as “John Shaa, goldsmith of London,” and on other occasions with no information other than his name.Footnote 30 It seems therefore that further prosopographical work is necessary before making firm conclusions regarding the social composition of the freeholders in the fines as a whole; in the meantime, we can draw some inferences based on those individuals for whom descriptive information is given and via analysis of general trends in the number of buyers and sellers. It should be emphasized, however, that the following analysis is based only on those records of individuals for whom we have information regarding their backgrounds, and for this reason it is likely to be weighted toward those of higher social status.

Table 4 displays recorded status of litigants in the fines according to social group and over time. Our results indicate dominance by two main groups: clergy and gentry, who between them account for three-quarters of all records in which the status of the individual is known. The clergy were the more numerous of these until the second half of the fifteenth century, when they were overtaken by the gentry, whose numbers had been steadily rising over the period. Members of the nobility and of merchants and craftsmen each represent 10–15 percent of the data, fluctuating slightly over time. Legal and administrative professionals appear only seldom in the fines until the late fifteenth century. The findings for the period 1300 to 1350 are broadly consistent with those of Barg in his analysis of the social composition of manorial freeholders in the Hundred Rolls of 1279.Footnote 31

Table 4 Status groups in fines over time and as percentage of total

In addition to the inconsistencies in the recording of this information described, there are a number of other issues to bear in mind regarding these data. The categories of nobility, gentry, and to some extent clergy include individuals bearing specific titles denoting their social status (such as lord, knight, or clerk). It is probable that these titles were more frequently recorded in the fines than those that were purely occupational in nature and therefore potentially subject to change. In addition, in cases in which several family members of the nobility or gentry were involved in a single transaction, every member of that family is counted as belonging to that social group (in contrast, for example, to a sale in which a merchant buys or sells property with his wife or children). We must therefore bear in mind the possibility that these groups are overrepresented in the data.

It is also necessary to acknowledge that the gentry, as a social group, remains a nebulous concept. In the current data set, the term has been applied to any individual termed knight, esquire, or gentleman, or members of their immediate family; however, as one of the defining criteria for membership of this class was ownership of land, there is an argument for applying this label to any freeholder with assets above a certain value.Footnote 32 The varying usage of these terms reflects the development of social gradation in the English gentry in the later medieval period.Footnote 33 The term esquire appears first in our data in 1383, and the term gentleman in 1389, reflecting legal recognition of these titles as denoting membership of the lesser gentry.Footnote 34 Although they were of a lower social status than knights, members of these groups were involved in land transactions of considerable value; for example, in 1467, John Cressy, gentleman, sold the manor of Luton and the hundred of Flitt in Bedfordshire for the sum of £500.Footnote 35 The relatively low numbers of gentry present in the sources in the first half of the fourteenth century (15 percent) may be interpreted as a result of the “crisis of the knightly class” of the thirteenth century, in which it is argued that, due to the prevailing economic conditions of the period, knights and lesser landowners suffered financial hardship that necessitated the sale of lands, often to large ecclesiastical institutions.Footnote 36 Alternatively, wealthier gentry may have alienated lands in mortmain to the church, in imitation of the philanthropic practices of the nobility of the time.Footnote 37

The high number of clergy present in the sources must be interpreted within the context of developments relating to property law of the period. The Statutes of Mortmain of 1279 and 1290 were designed to prevent land from falling into the “dead hand” of the church, and thus depriving the Crown of future revenue from taxation upon inheritance or alienation.Footnote 38 By the mid-fourteenth century it had become common for the church to evade this legislation through the appointment of feoffees, who became the legal holders of the property while the church remained in receipt of the profits via private agreement.Footnote 39 Similarly, during the second half of the fourteenth century, both secular and religious landowners took advantage of the enfeoffment to use, a legal instrument whereby property was transferred not directly to the intended beneficiary, but to a third party acting as trustee.Footnote 40 The purpose of this instrument was to avoid the financial costs associated with feudal tenure and to allow for greater freedom in the appointment of an heir. Members of the clergy, perceived to be more trustworthy and less self-interested than the rest of the population, were often appointed to act as trustees in this capacity.Footnote 41 Small groups of clergymen were generally appointed to act as trustees in such cases, perhaps to some degree resulting in their overrepresentation in the data. However, although enfeoffments to use were becoming increasingly popular in the later fourteenth century, studies of their numbers during this period indicate that they only account for a small proportion of transactions overall.Footnote 42 The results therefore suggest that members of the clergy were particularly active in the freehold property market. The majority of those clergy appearing in the fines were of relatively low status: over 90 percent are described as “clerk,” “chaplain,” “parson” or “vicar,” suggesting that most of these transactions constituted small-scale property purchases for personal gain, rather than the accumulation of extensive estates by religious houses.Footnote 43

What is the overall picture presented by this analysis of the social composition of litigants in the fines? Given that the social status of litigants is only recorded in 15 percent of cases, caution is necessary in using this information, as it could be influenced by changes in recording practices; we must therefore look to other sources as a means of corroborating these data. Yates matches litigants in the fines from Berkshire with taxpayers in the lay subsidy of 1327, finding that many were taxed very lightly; she thus argues that small freeholders were particularly active in the property market before 1350, but that their numbers declined over the course of the fifteenth century as access to freehold property became increasingly exclusive.Footnote 44 This is confirmed by analysis of trends in the values of properties bought and sold in the fines, which indicates that most of the plots transacted in the first half of the fourteenth century (in particular in the years following the Great Famine) were of low value.Footnote 45 The current study might at first appear to confirm these findings, in that we observe an increase in the number of litigants from gentry backgrounds over time, presumably at the expense of the small freeholder. However, in the next section, we will present data that complicate this picture. We discern a number of changes in buyer/seller behavior over the course of the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that indicate an increase in investment activity, which led to the opening up the of the freehold property market to new social groups.

Group Purchases

Through analysis of the individuals involved in the fines, we are able to discern a trend over time toward purchase of property as part of a group. This is indicated by an increase in the number of individuals involved in a single transaction. As Figure 2 demonstrates, until the late fourteenth century the average number of litigants in a fine remained between three and four: typically, a suit took place between a married couple (or sometimes other relatives such as a father and son) and a single buyer or seller or two couples. From the 1380s, however, the average number of litigants in a transaction begins to rise, and by the late fourteenth century, it hovered between four and six. We conducted a formal statistical test for whether the average number of litigants per transaction increases after 1400. The mean number is 3.49 in 1307–1400 and this rises to 4.97 in 1401–1508. This increase by more than 42 percent is statistically significant at all conventional levels (one-sided t-statistic for equality of means = 16.53 with p-value of 0.0000). This may be attributed to the changes in the size and makeup of landholdings outlined earlier; the increasing number of litigants involved in single transactions suggests that it was becoming more common for buyers to combine their resources to purchase large properties collectively. We should also bear in mind that this could in part be attributable to the rise in popularity of the enfeoffment to use as a means of transferring property, as these cases often involved groups of trustees; although, as noted earlier, these are likely to account for a relatively small proportion of transactions overall.

Figure 2 Average number of parties per transaction.

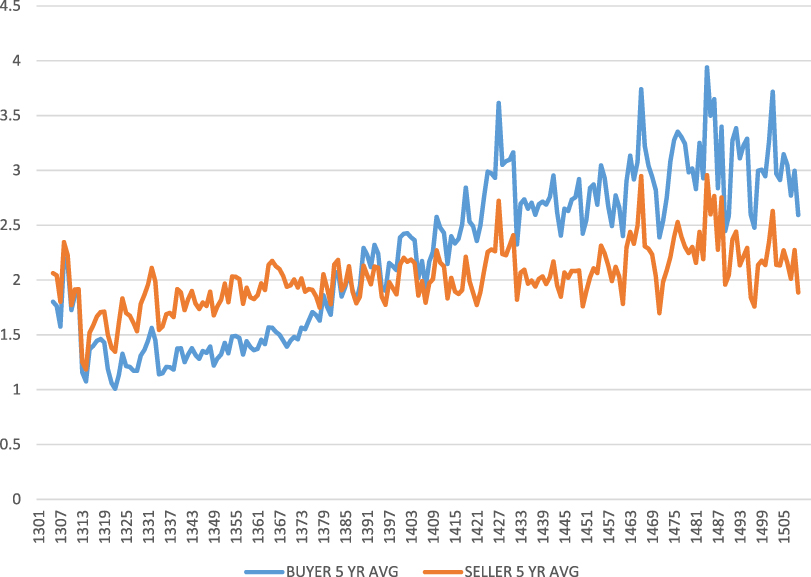

Figure 3 displays the average number of buyers and sellers per transaction between 1300 and 1500. This demonstrates that the overall increase in the number of individuals involved in a single transaction over the period may primarily be attributed to an increase in the number of buyers. Until the late fourteenth century, the number of sellers in a transaction typically outweighed the number of buyers, but after this date this relationship is reversed. The average number of sellers increases only slightly, from between 1.5 and 2 per transaction in the fourteenth century to between 2 and 2.5 in the fifteenth century. The number of buyers undergoes greater fluctuation, but demonstrates a substantial increase, from between 1 and 1.5 per transaction in the first half of the fourteenth century to more than 3 in the late fifteenth century. On the basis of these results, we argue that by the fifteenth century, the typical property purchaser was no longer a single individual or a married couple, but a small group that might include several unrelated individuals.Footnote 46 This suggests the existence of business partnerships or syndicates, groups of buyers who were motivated to purchase property collectively for reasons of financial gain; for example, in 1506 a group of nine men, apparently unrelated and including merchants, gentry, and members of the legal profession, purchased the manor of North Fareham and lands in the surrounding area from William and Mary Brocas, in whose family the estate had been since the late fourteenth century.Footnote 47 We find further evidence for this phenomenon in our analysis of individuals who engaged in multiple purchases (see “Multiple Transactions”). The increase in the number of buyers suggests a significant development in the nature of the market during this period, in that a greater proportion of the total population now had some kind of stake in freehold property. This may be interpreted within the context of a broader process of “democratization” of landownership in England in the wake of the Black Death.Footnote 48

Figure 3 Average number of buyers and sellers per transaction.

Multiple Transactions

Further evidence of investment activity in the freehold property market is the increase in the numbers of individuals who engaged in multiple transactions. Each person record in the database describes a single appearance of that individual in the sources; however, it is very difficult to determine whether multiple records in fact refer to the same person. It is possible to estimate this by searching for repetitions of individuals with the exact same first and second names, although it should be emphasized that due to the lack of standardized spelling, this method is unlikely to locate every instance of that person in the database. This analysis suggests that roughly 64,000 separate individuals appear in the transactions. The majority (more than 50,000) of these appear only once, suggesting that for most people during this period, a property transaction was a relatively isolated incident. Only 1,752 individuals (less than 3 percent) engaged in five or more transactions. The majority of these (1,160) were active post-1400, indicating that multiple property purchases were more common in the fifteenth century. The relative decline in numbers of fines per year after 1400 makes this figure all the more significant.

It is possible to identify twenty-three individuals who occur in ten or more transactions in the database, who we might tentatively term property investors (Table 5). The majority of these individuals were active during the fifteenth century in the Home Counties and Yorkshire. As might be expected, many of these men were prominent individuals who held high-ranking political or ecclesiastical office or members of the nobility such as Richard, Duke of Gloucester. However, some also came from relatively obscure backgrounds. The merchant William de la Pole, of “unknown origins” in Hull, forged a career in the first half of the fourteenth century as one of the most prominent merchants of the time and established himself as one of the key financial backers of the Hundred Years War.Footnote 49 Profits from his mercantile activity were invested into building up a substantial property portfolio, mainly in the counties of Yorkshire, County Durham, and Lincolnshire. In addition to being a source of income in themselves, these properties were chosen to support de la Pole’s business interests; his lands in north Yorkshire included estates in some of the best wool-producing districts, such as Swaledale, and most were situated near the great northern road running through Yorkshire and continuing up to Scotland, spaced at intervals so that they could serve as staging posts for his consignments of goods being carried up and down the country.Footnote 50

Table 5 Individuals involved in ten or more transactions

Others appear to have engaged in frequent property speculation at a lower level, such as the attorney John de Corbrigge, who appears in eleven fines in Buckinghamshire between 1373 and 1413 involving transactions of medium-sized parcels of land. In all but one of these cases, Corbrigge was the purchaser; the exception occurs in 1395, when he and his wife Joan are recorded as selling houses and land in Princes Risborough; as this is the only time Joan de Corbrigge appears in the fines, it is possible that these properties were hers. John de Corbrigge appears in many other Buckinghamshire fines, acting in his capacity as an attorney and representing those parties who were not of legal majority, which suggests that he may have used the connections made during his legal career to further his own property interests. Not all of the fines in which Corbrigge appears as a litigant are straightforward “sales”; in several he acts as a trustee in an enfeoffment to use, and would therefore have been holding the property for a limited term on behalf of its intended recipient.Footnote 51 However, it seems probable that in such cases the trustees would also have profited from the transaction, meaning that we can still class these transactions as representing a type of investment, even if the financial rewards were more limited. Members of the legal profession are well represented in the fines; other frequent investors in property include William Gascoigne, chief justice of the King’s Bench; John Fray, lawyer and later chief baron of the Exchequer; Humphrey Conyngesby, justice of the King’s Bench; and Richard Pygot, serjeant-at-law (Table 5).Footnote 52 Some rose from relative obscurity; Fray, for example, is described as “a particularly striking example of the ‘self-made man’ whose success was achieved through a combination of talent, hard work and personal ambition.”Footnote 53 These men illustrate the late medieval tendency for lawyers to achieve high social status through appointment to administrative posts and then to invest their earnings in property. Legal knowledge was useful for the successful administration of estates, and unlike trade, law as an occupation was compatible with gentry status.Footnote 54

Another example of an individual of relatively obscure origins occurring frequently in the fines is Thomas de Mussenden, a soldier in the service of Edward III. Mussenden had an intensive career as butler in the royal household from 1338 to 1344 and served the king on campaign in the Low Countries (1338–1339), Sluys and Tournai (1340), and Brittany (1342–1343), on the abortive expedition to Flanders (1345), and during the Normandy–Crécy campaign (1346).Footnote 55 As an investor, he was involved in twelve transactions in Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire between 1340 and 1364. Through his military service and marriage to Isabel, a member of the influential Brocas family of Lincolnshire, Mussenden was able to achieve a degree of social and political prominence and was eventually knighted.Footnote 56 Again, with one exception, all Mussenden’s transactions in the fines were purchases, indicating his desire to build up an estate. His properties included interests in the manors of Quainton and Overbury, both of which he passed on to his son, Edmund.Footnote 57 It is presumably through the acquisition of these manorial estates that Thomas was able to arrange the marriage of Edmund into the nobility.Footnote 58

The example of a soldier perhaps investing “profits” of war in investment properties leads us to reflect on whether this might have been a regular occurrence. What profits, if any, could actually be made from warfare?Footnote 59 There are celebrated cases of leading and well-connected soldiers returning from France during the period of the Hundred Years War with large bounties. For instance, the case of Sir John Fastolf, who McFarlane estimates spent around £24,000 on acquisitions, including enlarging his own real estate portfolio.Footnote 60 What about other ranks of soldier? All English armies were paid, and it can be assumed that the daily rate for a mounted archer of 6d per day, even though also covering expenses, may have made military service a profitable alternative to other forms of manual labor or working as a skilled craftsmen.Footnote 61 Plenty of evidence survives that demonstrates that mobility was available for skilled military practitioners and that it was possible to begin a career as an esquire or even an archer and gain promotion to knight—with the extreme example of the career of Sir Robert Knolles.Footnote 62 It is less clear whether this military advancement could also lead to social mobility in the local context, and this aspect deserves more research. This is indeed possible now that large data sets have been collected in support of research into soldiery during the Hundred Years War.Footnote 63 There are also fleeting examples that provide some insights. For instance, we are able to gain wealth data for the archer Thomas Huxley, a former bodyguard of Richard II, killed at the battle of Shrewsbury in 1403, for whom we therefore have an inquisition post mortem. This demonstrates that his landed property at the time of death included “three messuages and a water mill in Huxley worth £5 per year, a messuage in Rowecristleton worth 8s per annum, and a further messuage along with 20 acres in Sydenhale worth 10s a year.”Footnote 64

The activities of men such as de la Pole, Corbrigge, and Mussenden provide evidence of the potential in the late medieval period for those from the mercantile and professional classes to purchase property as a means of rising up within the social hierarchy. In the case of Mussenden, this enabled him to establish his family among the landed gentry. In this respect, the fact that he was buying properties in the counties of Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire is significant; previous studies have highlighted proximity to London as a determining factor in this phenomenon.Footnote 65 A useful comparison may be made with a recent study examining the fines for Warwickshire in the late thirteenth and first half of the fourteenth century.Footnote 66 Analysis of the social background of the frequent purchasers in this county reveals that they are among the wealthiest individuals in the region and predominantly from the higher gentry and nobility.Footnote 67 This suggests that, in the period before the Black Death and in counties farther away from London, property purchase was less of a conduit to social mobility.

It should be noted that Table 5 perhaps overstates the case for multiple purchases by individuals rising over time, as it appears that a number of individuals within it were connected and engaged in property transactions together; several of the transactions listed here have therefore been “double-counted.” For example, the Yorkshire landowners William and Richard Gascoigne were brothers, and in five of the fines shown here they appear as co-litigants. Furthermore, it appears that the last eight individuals named in this table participated in property transactions as a collective on numerous occasions during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, both within the counties under discussion in this paper and in several other regions. Various combinations of these eight men acting together appear in forty-two fines dating from between 1496 and 1505, mainly concerning properties in Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire, but also in the counties of Middlesex, Yorkshire, Hampshire, Worcestershire, Essex, Sussex, and Rutland. The group included several influential officials of the royal administration, such as Sir Richard Empson, Sir Reginald Bray, and Sir Humphrey Conyngesby, and high-ranking ecclesiastical figures such as William Smyth, the bishop of Lincoln, and Hugh Oldham, who would be appointed bishop of Exeter in 1505.Footnote 68 Empson appears to have been the central figure in this group, participating in all but two of these transactions. He was the son of a minor Northamptonshire landowner, who used his political connections to build up a considerable landed estate. As chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and one of the king’s councilors, he became associated with the harsh taxation policies of Henry VII, and after the king’s death in 1509, he was made a scapegoat by Henry VIII and executed for treason.Footnote 69 As might be expected considering the power and wealth of the individuals concerned, many of the properties detailed in these fines were extensive in size and worth considerable amounts of money; for example, in 1503, Empson, Bray, Oldham, and several other bishops and nobles were claimants in a suit involving properties spread over six counties, including several manors and thousands of acres of land, for which the monetary consideration was recorded as £1,000.

An attempt to trace the history of some of the manors mentioned in these transactions in the relevant volumes of the Victoria County History is revealing.Footnote 70 It appears that, in all of these cases, the actual holder of the title to the manor was either Bray or Empson; in the case of the former, the title was then passed on to his heirs, whereas Empson’s property reverted to the Crown after his trial and execution.Footnote 71 This raises a number of questions regarding the role of the other participants in these suits. It is possible that these men were merely acting as guarantors and had no claims to the property in question. However, in most cases, manors were only one element of the property described in the fines; they also included various other lands, buildings, or revenues in the local area. It is therefore possible that these assets became the property of the other litigants, although the vague nature of these descriptions means that the task of tracing their ownership in the sources is problematic.

It should be noted that not all of those who frequently occur in these sources are success stories. Sir Richard Abberbury (d. 1416) was a member of a prominent gentry family; his father and grandfather had between them built up one of the largest estates in Oxfordshire and Berkshire.Footnote 72 Richard had a successful political career in the service of John of Gaunt, and by 1387 had risen to be his chamberlain. In the late fourteenth century, he is recorded in several fines adding to his family estates through the purchase of property in Berkshire, Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, and Warwickshire. However, despite Richard’s good standing at the Lancastrian court, the succession of Henry IV to the throne marked the beginning of a decline in the family fortunes.Footnote 73 Richard’s political career appears to have stalled, and in 1415 he began to sell off his family estates (inherited in 1399), including the family manor of Donnington, which was sold along with other properties to Thomas Chaucer for 1,000 marks.Footnote 74 It seems probable that the explanation behind this mass sale lies in Richard’s interest in the revival of crusading that occurred around this time; he spent an increasing amount of time abroad and was recorded as a member of Philippe de Mézières’s Order of the Passion by 1395.Footnote 75 It seems that this pursuit either left him in financial difficulties, which necessitated the sale of his lands, or that he had decided to exchange his real estate portfolio for cash to fund his overseas activities. Thereafter, the Abberbury family sank into relative obscurity, underlining the importance of land to the maintenance of social status.

Distance Between Buyer and Property

Finally, we now consider the third indicator of investment activity in the property transactions recorded in the feet of fines, concerning the proximity of the buyer or seller to the property in question. As stated earlier, just over one-quarter of the descriptions of the individuals involved in the fines include information on their regional origins. When compiling the database, a field was included to record whether the place of origin of the individual was 30 km or less from the location of the property transacted; depending on this calculation, individuals were then described as “local” or “not local” (based on the assumption that this refers to a current rather than a former place of residence). This distance was selected as roughly representing the limits of one day’s travel in the medieval period; James Masschaele suggests that the regional influence of medieval towns extended to a radius of approximately 20 miles.Footnote 76 This is obviously a very rough estimation and does not allow for detailed analysis of the distances involved; any conclusions we draw from this analysis should therefore be tentative. Furthermore, the fact that this information does not always occur in the sources means that the results could be as much influenced by recording practices as by trends in market activity.

Bearing this in mind, the analysis does reveal some discernible overall trends. Of the 24,641 cases in which information is given regarding the regional origin of the parties in a transaction, 19,893 individuals were deemed to be local, and 4,748 not local, to the area in which the property is situated. Sales featuring nonlocal participants therefore make up almost one-quarter of all cases in which the origin of the individual is recorded; considering the comparatively low geographical mobility of the late medieval English population, this is higher than expected.Footnote 77 In approximately two-thirds of these cases, the individuals concerned were selling property, and in one-third of cases they were purchasing it. It is possible to attribute this in part to recording practices, as regional origin was more often recorded for sellers than buyers (see Table 2); however, it could also suggest the sale of inherited property. The places of origin of nonlocal participants are varied, but a significant proportion of them came from urban centers: 873 came from London, 54 from York, 44 from Lincoln, 23 from Coventry, 21 from Hull, and 20 from Beverley. Transactions featuring nonlocal buyers or sellers appear to be particularly common in the second half of the fourteenth century (Figure 4); they peak during the 1380s, when they account for 14 percent of all transactions registered.

Figure 4 Transactions featuring nonlocal participants as percent of total.

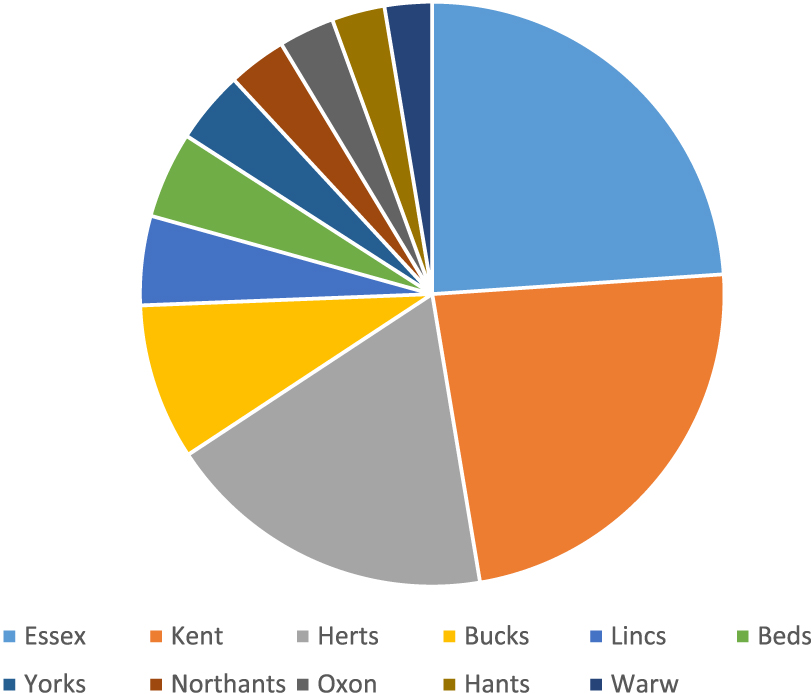

One of the most interesting results is the high proportion of Londoners among the nonlocal participants. There were 518 sales in total in which Londoners were involved. Most of these sales took place in the south of England, in particular the neighboring counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, and Bedfordshire, but a significant proportion also involved property in the northern counties of Yorkshire and Northumberland, and also in the Midlands (see Figure 5). An example of property investment by Londoners very far from home occurred in 1386, when William Hyde, John Walcote, and Gilbert Manfeld, citizens of London, purchased the manor of Adderstone and nearby lands in Northumberland from John Chartres (see Appendix). Properties purchased by Londoners ranged in size from single messuages with a few acres of land to large estates with multiple dwellings and hundreds of acres of meadow and pasture to entire manors. Information regarding occupation and status is more frequently recorded for Londoners than for the rest of the population (in 1,090 of 2,069 cases), allowing for a more detailed analysis of the social background of the buyers and sellers (Table 6). As might be expected, the majority of these individuals are described as having occupations associated with London’s crafts and mercantile guilds. The major livery companies (the Mercers, Grocers, Drapers, Fishmongers, Goldsmiths and Skinners) account for most of these, but there are also members of more obscure guilds such as the Woodmongers’ Company.Footnote 78 The nonmercantile London litigants include a few minor gentry, some high-status clergy, and a few other occupations such as that of hosteler, barber, and leech. There are 250 occasions in which London women were named as litigants in the fines. In the overwhelming majority of these cases, these women were buying or selling property with their husbands. An exception occurred in 1426, when Joan Haworth, the widow of the London dyer Thomas Haworth, and the dyer John Stanstede are recorded as selling two shops in St. Albans to the hatter William Hervy; presumably Stanstede was an associate of Haworth who was helping his widow dispose of her late husband’s property.Footnote 79

Figure 5 Transactions featuring Londoners by county. Herts, Hertfordshire; Bucks, Buckinghamshire; Lincs, Lincolnshire; Beds, Bedfordshire; Yorks, Yorkshire; Northant, Northamptonshire; Oxon, Oxfordshire; Hants, Hampshire; Warw, Warwickshire.

Table 6 Londoners in the fines according to status group

These results are not perhaps particularly surprising; the ability of London’s citizens and mercantile classes to use their disposable income to invest in property is well documented from the thirteenth century onward.Footnote 80 The primary attraction of property as an investment for merchants lay in its ability to provide a lucrative source of income in the form of rent and (particularly in the case of manors) to secure higher social status. While the number of merchants who attained gentry status via this means is debatable, both Thrupp and Kermode record several examples of this phenomenon regarding London and Yorkshire merchants, respectively.Footnote 81 Some individuals can be seen to be actively attempting to build up estates in a certain area; the grocer and sometime mayor of London Thomas Knolles, for instance, purchased one-quarter of the manor of North Mimms in Hertfordshire in 1392 and several other properties in the area in 1417; in 1428, Knolles and several other London merchants are recorded as purchasing the remainder of the manor, which was settled on his son Thomas after Knolles’s death in 1435–6.Footnote 82 An indication of the sometimes ruthless business practices of mercantile investors is demonstrated in the fact that, on his acquisition of the manor, Knolles raised the rents; when faced with complaints from the tenants, he claimed that this was not his decision but that of his wife Joan, who had also been involved in the sale and had the responsibility of running the estate.Footnote 83 In addition to the acquisition of social status, property was often used by merchants to provide security for loans and to pay off debts.Footnote 84 London merchants were well placed to take advantage of credit arrangements; a possible example of this in the fines may be seen in the purchase of the manor of Thele in Stanstead St. Margarets, Hertfordshire, by the mercers Richard Riche, Thomas Bataille, and Robert Large in 1436. All three men had accounts with the Italian Borromei Bank around this time, which would have enabled them to access capital for making large investments of this kind, particularly in the case of Bataille, who, unlike the other two men, was not particularly wealthy.Footnote 85

While Londoners’ property holdings were spread over a wide geographic area, the most common region of investment was the Home Counties; more than three-quarters of transactions took place in the counties of Essex, Kent, Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, and Bedfordshire. It therefore seems likely that investment in property in neighboring counties by Londoners was a significant factor in the increased level of market activity in these areas.Footnote 86 Londoners were also involved in purchasing property in the West Midlands and the north of England. It is possible that in some of these cases the litigants originated in that area and had maintained family connections and interests in property; immigration to the city rose substantially over the fourteenth century, and both the guilds and the central government administration recruited a significant proportion of their apprentices from the provinces (in the case of the latter, specifically from the counties of Lincolnshire and Yorkshire).Footnote 87 It is possible that Londoners’ business interests in certain areas also resulted in property acquisition, as was the case in Great Yarmouth and its surrounding towns.Footnote 88 Others may have acquired property through an advantageous marriage.Footnote 89

The fines also feature a number of cases in which members of London’s governing elite are recorded as participating in property transactions outside the city. In addition to a number of mayors and aldermen (who were often from mercantile backgrounds), these included several of the professional clerks and legal officials who were responsible for the day-to-day running of the city from its administrative center, the Guildhall. Most notable among these are John Carpenter, Common Clerk of the Guildhall from 1417 to 1438 and author of the Liber Albus, the first book of English common law, and Richard Osbarn, Clerk of the Chamber of the Guildhall from 1400 to 1437.Footnote 90 Both of these men were involved in sales of property in Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, and Bedfordshire in the early fifteenth century, sometimes together (Carpenter was one of a small group of men who purchased goods and rents in Furneux Pelham, Hertfordshire, from Osbarn in 1433). Other sources record Carpenter and Osbarn as holding joint interests in a number of properties both within and outside the city; it has been suggested, however, that in some of these cases they were not motivated by personal gain, but were acting as administrators of charitable bequests on behalf of widows or orphans.Footnote 91

Conclusions

It is possible to draw several conclusions from this analysis. Evidence from the feet of fines suggests that the freehold property market in the first half of the fourteenth century was dominated by small landowners, often members of the lower clergy. After 1350, we observe several trends indicative of investment activity: it became increasingly common for people to buy or sell property as part of a group, enabling the purchase of more extensive properties and increasing the opportunity for profit; a rising number of people were involved in multiple transactions; and many individuals (particularly those from London) had property interests at a distance from their places of residence, indicating purchase for means other than consumption. There are indications that those in certain occupations, such as soldiers, merchants, and legal professionals, were able to accumulate sufficient capital to engage in property speculation, and on occasion this effected their means of entry into the landed gentry. The apparent increase in the number of gentry freeholders in the fifteenth century should be interpreted within this context.

These findings have implications in a number of key areas of research on the late medieval English economy. The first of these is the role of property in social mobility, particularly in the period following the Black Death. Previous work in this area has emphasized the difficulties inherent in estimating the extent of social mobility during this period. Maddern presents a number of case studies demonstrating that it was possible for families to rise up within the social hierarchy by means of marriage, political career, or industry; however, she argues that it is difficult to say how representative these cases were of broader trends, and ultimately concludes that they represented the exception rather than the rule.Footnote 92 This pessimistic view of social mobility in late medieval English society is contrasted by those who argue that the Black Death resulted in an increase in economic opportunities, particularly for the newly wealthy, who had until this point been excluded from property ownership.Footnote 93 Our data provide much-needed quantitative evidence in this area. We find that more people were involved in the freehold property market than at any previous point in time, suggesting a more even distribution of land. This suggests that those who had acquired wealth through a professional career or through trade or military success were able to convert this wealth into status through the acquisition of property.Footnote 94

This study highlights the economic dominance of London from the end of the thirteenth century in terms of population, international trade, and the provision of credit.Footnote 95 Keene’s analysis of debt cases in the Court of Common Pleas demonstrates that, over the course of the fifteenth century, London was drawing in business at the expense of its surrounding counties and was the main provider of credit to the provinces; this is particularly notable in the counties of Essex and Kent.Footnote 96 The fact that our evidence suggests these regions were key sites of property investment by Londoners during the fifteenth century raises the possibility that these properties were acquired at a reduced price in lieu of debt payments; this is supported by Keene’s findings that provincial debtors to London were predominantly from the “landed” classes.Footnote 97

Our data on the regional origins of buyers reveal that a substantial number came from cities and towns other than London; buyers from York, Coventry, and Boston are particularly numerous. Further analysis of these data has potential to contribute to the long-running debate on urban decline in late medieval towns.Footnote 98 The number of buyers from each of these locations appears to decline during the fifteenth century, suggesting that in these cases, property investment declined in line with wider urban economic conditions such as population levels, industry, and trade.Footnote 99 Analysis of the occupational data of buyers reveals the increasing specialization of urban industries.Footnote 100 Those professions involved in the manufacture and sale of cloth and clothing, such as mercer, draper and tailor, are best represented, reflecting the typical occupational structure of later medieval urban society.Footnote 101

The data collected for this study offer ample opportunities for further research. In particular, it would be useful to conduct additional case studies of individual buyers and sellers in an attempt to build up a picture of their financial activities and whether these were conducted with a sense of any long-term strategy: Is it possible, for example, to find evidence of a property being purchased by an individual and sold at a later date for a higher price? Another potential topic to which analysis of the fines might contribute is the role of credit in the medieval property market. Detailed investigation of the circumstances of individual litigants in the fines might reveal, for instance, that they sold property in order to repay debts or entered into a credit arrangement in order to make new purchases; evidence for this could be seen in those fines that refer to an annual payment to be given to the seller rather than a consideration in the form of a lump sum. Further research of this kind will allow us to build up a more nuanced understanding of the workings of the medieval market in freehold property and the motivations of those who participated in it.

Appendix

TNA, CP 25/1/181/14, number 16 (1386)

This is the final agreement made in the court of our Lord the King at Westminster, fifteen days after Michaelmas in the tenth year of the reign of Richard king of England and France, before Robert Bealknapp, William de Skipwyth, John Holt and William de Burgh, justices of our Lord the King, and other faithful people then and there present, between William Hyde, John Walcote and Gilbert Manfeld, citizens of London, querents, and John Chartres, deforciants, regarding the manor of Adderstone with its appurtenances and of 11 messuages, 260 acres of land, 20 acres of meadow, 200 acres of pasture and 40 acres of wood in Overgrass and Newton-on-the-Moor. Whereupon a plea of covenant was summoned between them in the same court, that is to say that the aforesaid John Chartres has acknowledged the aforesaid manor and tenements with the appurtenances to be the right of Gilbert, and those he has remised and quitclaimed from himself and his heirs to William, John Walcote and Gilbert and the heirs of Gilbert for ever. And moreover the said John Chartres has granted that his heirs will warrant to the aforesaid William, John Walcote and Gilbert and the heirs of Gilbert the aforesaid manor and tenements with the appurtenances against all men for ever. And for this recognizance, remise, quitclaim, warranty, fine and agreement the said William, John Walcote and Gilbert have given to the said John Chartres four hundred marks of silver.