Introduction

Is the COVID-19 pandemic a critical juncture? An emerging social scientific scholarship on the COVID-19 pandemic has set out to study its effects on a range of social, political, and economic phenomena. Some of this scholarship makes the claim that the pandemic is a key historical turning point during which long-standing institutional frameworks are being overhauled and new policy pathways are being established. In other words, this scholarship theorizes that the COVID-19 pandemic is one of those rarest and most impactful moments in time, what historical institutionalists would call a “critical juncture.” If this is indeed the case and the COVID-19 pandemic is in actuality a critical juncture, then this would mean that social scientists now have a unique opportunity to move away from the everyday work of explaining continuity to studying dynamics of change on a global scale. It could also mean that we may yet find a silver lining to a pandemic that has devasted lives and livelihoods on a global scale: for all the harm that it has caused, the pandemic may also prove—as this special issue suggests—to be a driver of innovation.

There are other important reasons for determining whether the pandemic is a critical juncture. Firstly, this can clarify an emerging debate over the pandemic’s effects: there are scholars who argue that, instead of being a critical juncture, the pandemic is a path-clearing accelerator—simply accelerating the development of long-standing policy pathways—and others who contend that its effects on social, political, and economic phenomena are overstated. Secondly, scholars have heavily theorized critical junctures, but critical juncture theories continue to be tested (Collier and Munck Reference Collier and Munck2022); a study of the COVID-19 pandemic therefore contributes to this ongoing scholarly endeavour. Thirdly, and perhaps more generally, it can tell us whether we must depend on unpredictable events to drive innovation or whether agency can still factor in some way.

This article assesses the critical juncture hypothesis using a process tracing method. In so doing, it explores recent developments in multilingual governance techniques in the United States, focusing on the delivery of multilingual services on governmental websites and on COVID-19–related multilingual bills. The United States is an ideal case to test for the observable implications of a COVID-19 critical juncture hypothesis since (at least at first blush) it appears to bear the hallmarks of radical change following the pandemic’s onset. At the federal level, the two agencies most directly responsible for the government’s response to the pandemic have implemented translation tools and multilingual services in the dissemination of COVID-related health and sanitary measures. At the state level, changes appear to be far more striking. Since the pandemic’s onset, health departments in ten “official English” states—states that have formally or symbolically embraced monolingualism—have implemented multilingual governance techniques.

Taken together these developments seem to signal more than just a significant change in American language policy. They also point to a divergence from the global pressure to communicate pandemic-related information in English (Piller, Zhang, and Yi Reference Piller, Zhang and Li2020) and to a stark contrast from the Canadian experience, where, during the pandemic, “a gradual loosening of linguistic obligations in public institutions and governments has been observed in various jurisdictions” (Chouinard and Normand Reference Chouinard and Normand2020, 259). In brief, these developments seem to support the thesis that the COVID-19 pandemic is a critical juncture.

The findings of this article reveal otherwise. In testing for two observable implications of the COVID-19 critical juncture hypothesis, this article will show that the American case fails to support either of them. More specifically, it will show that, at the federal level, the implementation of new governance techniques was not preceded by radical institutional change. It also will show that, at the state-level, there is evidence that the implementation of multilingual governance techniques in “official English” states is in actuality the continuation of policy pathways established prior to the pandemic. Consequently, the American case weakens the COVID-19 critical juncture hypothesis rather than confirming it.

This article is structured as follows. The first section expands on the theoretical discussion concerning the pandemic’s effects. Following that, the next two sections outline this article’s methodology and case study rationale, respectively. The article subsequently provides a descriptive overview of the main developments of multilingual governance in the United States leading up to and following the pandemic’s onset. It then tests for the two observable implications of the COVID-19 critical juncture hypothesis in the American case. The article concludes by discussing alternative understandings of COVID-19’s effects in light of the evidence presented in preceding sections and by addressing what the article’s findings might mean for the study of the pandemic moving forward.

I. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Critical Juncture or Not?

Many recent studies view the COVID-19 pandemic as a “critical juncture,” thus drawing (albeit loosely) upon a concept that is most commonly associated with historical institutionalism. Historical institutionalism understands critical junctures as “moments of openness for radical institutional change, in which a relatively broad range of options are available and can plausibly be adopted” (Capoccia Reference Capoccia, Fioretos, Falleti and Sheingate2016, 104). A critical juncture is brought about by an exogenous shock, which is a largely unexpected development—such as “[an] economic crisis, a regime transition, a war, or [an] other important event” (Bertrand Reference Bertrand2004, 25)—that upends routine political, economic, and social exchanges. Once an exogenous shock opens up a critical juncture, power dynamics in society and within organizations enter a state of flux, and changes to longstanding norms, conventions, formal rules, and entrenched public policies become a distinct possibility. The outcomes of a critical juncture are somewhat contingent on the “historical social and political context” (Capoccia Reference Capoccia, Fioretos, Falleti and Sheingate2016, 98) that precedes the exogenous shock. Nevertheless, scholars argue that critical junctures have led to the displacement of societal, political, and economic institutions that may have once seemed immutable (see Collier and Collier Reference Collier and Collier1991; Pierson Reference Pierson2000).

Studies that view COVID-19 as a critical junctureFootnote 1 cover a wide range of phenomena. For example, in case studies of the United Kingdom, Waylen (Reference Waylen2021) argues that the pandemic facilitated the emergence of “hypermasculine leadership,” while Joyce (Reference Joyce2021) argues that it produced a procedural change in health crisis management strategies from a “siloed” to a “whole-of-society” approach (Joyce Reference Joyce2021). Hajnal, Jexiorska, and Kovács (Reference Hajnal, Jexiorska and Kovács2021) and Giovannini and Mosca (Reference Giovannini and Mosca2021), in case studies of Hungary and Italy, respectively, contend that the pandemic is a critical juncture during which national governments have enacted laws and developed new organizations to centralize power in an unprecedented way. Several recent studies of supranational organizations (for example, Ladio and Tsarouhas Reference Ladio and Tsarouhas2020; Albertoni and Wise Reference Albertoni and Wise2021) point to the pandemic as a critical juncture that has entailed major changes to international norms. Other studies point to changes in societal norms—notably in the development of a greater sense of solidarity across socio-economic strata (see Ferragina and Zola Reference Ferragina and Zola2022; Fiske et al. Reference Fiske, Galasso, Eichinger, McLennan, Radhuber, Zimmermann and Prainsack2022)—as evidence of a COVID-19 critical juncture. Finally, and at a more speculative level, some studies (for example, Béland et al. Reference Béland, Lecours, Paquet and Tombe2020; Rocco, Béland, and Waddan Reference Rocco, Béland and Waddan2020; Ramia and Perrone Reference Ramia and Perrone2023) argue that the COVID-19 pandemic may, over the longer term, prove to be a critical juncture during which federal states rebalance powers and competencies between orders of government.

To be clear, not all recent discussions on COVID-19 view the pandemic as a critical juncture. There are some studies that describe the COVID-19 pandemic as a “path-clearing” event. Hogan, Howlett, and Murphy (Reference Hogan, Howlett and Murphy2022) have developed a theory of policy change that identifies path-clearing as the fourth of the five “punctuations” on a policy change pathway. These five punctuations are highlighted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. “Policy Punctuations” on the Policy Change Pathway

Path Initiation → Path Reinforcement → Critical Juncture → Path Clearing → Path Termination

Source: Hogan et al. (Reference Hogan, Howlett and Murphy2022, 44–46)

The first punctuation on the policy change pathway (i.e., “path initiation”) “can see the creation of new policies and the consequent initiation of a policy pathway” (Hogan, Howlett, and Murphy 45), while the second punctuation (i.e., “path reinforcement”) reinforces the new policy pathway through routinization and as a result of feedback mechanisms and the strategic actions of policy entrepreneurs (ibid.). The third punctuation on the pathway is the critical juncture. For Hogan et al., a critical juncture is “a moment when a path changes direction” (ibid.). A critical juncture is then followed by a fourth punctuation, which can either be “path-blocking” or “path-clearing.” On the one hand, a “path-blocking” punctuation emerges when barriers are rapidly erected to prevent further changes to the new policy pathway created during the critical juncture. On the other hand, a “path-clearing” punctuation facilitates further policy changes to the new policy pathway created during the critical juncture by “allowing policy choices which would have been otherwise more difficult to make occur, speeding up or accelerating event sequences along the pathway” (ibid.). A fifth and final punctuation on the policy change pathway (i.e., “path termination”) is apparent when the new policy path created during the critical juncture comes to a sudden or gradual end.

Hogan et al. argue that the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be considered a critical juncture because it has not “affected all policy areas equally across-the-board” (ibid., 46) and that, given the mounting evidence that it has sped up the implementation of several pre-existing policy pathways, it must be a path-clearing accelerator. Other studies draw a similar conclusion. For example, Dupont, Oberthür, and von Homeyer (Reference Dupont, Oberthür and von Homeyer2020) argue that COVID-19 is speeding up the implementation of a policy consensus arrived at during a pre-pandemic critical juncture, one that resulted in the 2019 European Green Deal. Similarly, Kuzemko et al. (Reference Kuzemko, Bradshaw, Bridge, Goldthau, Jewell, Overland, Scholten and Westphal2020) contend that the COVID-19 global pandemic is simply accelerating the development of a new policy pathway created during a critical juncture that lasted from 2010 to 2016 and resulted in the Paris Agreement and in the articulation of a politics of sustainable energy transition. Carrapico and Farrand (Reference Carrapico and Farrand2020) argue that the global pandemic has cleared the path for the adoption of a cross-national strategy to tackle the spread of disinformation, the need for which was first signaled during a critical juncture bookended by the European Union’s Joint Communication on Hybrid Threats in 2016 and subsequent revelations of data harvesting by Cambridge Analytica. And, in a recent study of economic policy, Chohan (Reference Chohan2022) argues that the pandemic may be path-clearing for a far older critical juncture that resulted in the emergence of Keynesianism and in the wide-spread adoption of social protections during the early- to mid-twentieth century.

In addition to the studies that develop path-clearing rebuttals to critical juncture arguments, there are a handful of studies that bring into question the pandemic’s causal influence. For instance, Lee, Chau, and Terui (Reference Lee, Chau and Terui2022) argue that while the COVID-19 pandemic has been path-clearing in South Korea and that it has opened up a critical juncture in Japan, it had no effect whatsoever on cultural policy in China. They attribute the pandemic’s non-effect in China to regime type and to the limited degree of latitude this regime affords to “institutional entrepreneurs” during moments of crisis (ibid., 159). Hanniman (Reference Hanniman2020, 282), in a case study on Canadian fiscal federalism, cautions against assuming that the global pandemic is leading to a critical juncture because decisions regarding provincial debt have yet “to reach a critical choice point.” Accordingly, Hanniman’s case study points to “the pitfall of radically dividing history into periods of institutional stability and change” (ibid.) and, in so doing, of overlooking the adaptability of Canadian federal institutions.

An assumption that COVID-19 is a driver of change can also mean that observers miss gradual and subtle forms of institutional change. Bulmer (Reference Bulmer2022, 177) advances this argument when examining Germany’s collaborative fiscal response to the pandemic, which, by all appearances, was an abrupt break from the country’s “long-standing opposition to mutualising debt.” Bulmer contends that what one is actually witnessing is the redeployment of existing policy instruments and not a radical change in the policy pathway. In so doing, he draws attention to an alternative to critical juncture explanations of radical institutional change—a theory of gradual institutional change involving processes of institutional conversion, layering, and drift (see Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010).

As one can see in the preceding pages, there is little agreement about the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects. To be sure, studies that paint the pandemic as either a critical juncture or as path-clearing tend to agree that it is impactful, but they differ in their understandings of the nature of its impact. In turn, these studies generate two major interpretations of the outcomes that the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to produce. The prominent interpretation is that the global pandemic is a critical juncture during which radical institutional change occurs and new policy pathways are created. The other is that the pandemic is simply accelerating changes that are themselves the result of a pre-pandemic critical juncture. There is also room for a third interpretation: that the pandemic’s effects as a driver of change are perhaps being overstated. This could mean that the institutional status quo is persisting or that institutions are changing in a gradual and subtle fashion in a manner unrelated to the pandemic. In brief, the foregoing discussion shows that simply because change occurred after the pandemic’s onset, this does not necessarily mean that the pandemic is a critical juncture.

II. Hypothesis and Methods

We are still at the preliminary stages of adjudicating between rival explanations of the pandemic’s effects. This article’s modest contribution to this endeavour is to see whether it can infirm the proposition that the COVID-19 pandemic is indeed a critical juncture. Theory-infirming studies can represent a crucial first step in the theory-testing process: at the bare minimum they can serve to “weaken…generalizations” (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1971, 692), but, in some cases, they can also “provide definitive tests for hypotheses” (Gisselquist Reference Gisselquist2014, 478). Either way, a theory-infirming approach is particularly important when beginning to explore a new and potentially important phenomenon—such as the COVID-19 pandemic. It can steer scholars away from an unfruitful research avenue.

This article tests the hypothesis that the COVID-19 pandemic is a critical juncture which is resulting in the development of new governance techniques. The article tests the hypothesis by process-tracing, a method that, very generally speaking, involves “a close processual analysis of the unfolding of events over time within the case” (Collier Reference Collier and by1993, 115). Process-tracing can mean identifying the complex causal mechanisms that connect independent and dependent variables and, in the specific case of critical juncture analysis, bringing to light the key “turning points” (Levy Reference Levy2008, 12) in temporal sequences. Hypothesis-testing through process-tracing begins by describing the “observable implications” (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2007, 131) of the hypothesis and then determining whether they are present in a case that exhibits the predicted relationship between independent and dependent variables. If they are not present, the hypothesis is infirmed.

The hypothesis that this article tests has two key observable implications. A first observable implication is that since critical junctures are “moments of openness for radical institutional change,” they are evidenced if and only if institutional frameworks do actually change following an exogenous shock. This implication draws a distinction between institutions understood as formal and informal constraints on human behaviour, public policy understood as governmental decisions, and governance techniques defined as tools and instruments employed by government departments and agencies. What it further suggests is that the decision-making process is a sequence that begins with the opportunities and constraints established by the formal institutional framework and is then followed by policy-making and the implementation of governance techniques. Consequently, changes in public policy and the implementation of new governance techniques are insufficient indicators that COVID-19 is a critical juncture. For COVID-19 to be considered a critical juncture, changes in public policy and the implementation of new governance techniques must also be preceded by some form of radical institutional change.

The second observable implication is that a critical juncture must result in a fundamental change in techniques and not just speed up the implementation or expansion of a pre-exiting pathway (in which case the event could be considered a path-clearing accelerator). This means that for COVID-19 to be considered a critical juncture, there must be evidence that it is an actual “turning point” and thus that the governance techniques that are implemented in its wake are truly and uncontestably innovative. In other words, if there is evidence that seemingly “new” techniques were actually implemented prior to COVID-19, then the pandemic cannot be considered a critical juncture.

III. Multilingual Governance

In order to test the COVID-19 critical juncture hypothesis and its observable implications, this article focuses on multilingual governance. Multilingual governance can be a significant feature of a polity’s language policy. The implementation of multilingual governance entails the use of translation tools and interpretation services by the public administration and by governmental agencies and departments in the performance of their duties and in their interactions with citizens. Multilingual governance is sometimes implemented in order to ensure “fair terms of integration” (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka2001, 162) for immigrants who are not proficient in the receiving country’s majority language(s). In polities with territorially concentrated national minorities or Indigenous peoples, or both, multilingual governance has sometimes been implemented under the ambit of “multiculturalism policies” (see Banting and Kymlicka Reference Banting and Kymlicka2004) and resulted in the formal or constitutional recognition of linguistic pluralism. Multilingual governance stands in contrast to monolingual governance. The implementation of monolingual governance means, more precisely, that “the burden of translation is just shouldered by the non-institutional interaction partners who will need to find resources to translate all correspondence to and from the only accepted language” (Koskinen Reference Koskinen2014, 484).

The study of multilingual governance is ideal for assessing whether the COVID-19 pandemic is or is not a critical juncture. For one, multilingual governance is a relatively new institutional phenomenon, whereas de jure or de facto “monolingual governance” has long been the norm even in deeply diverse societies. Therefore, the implementation of translation and interpretation services or the formal recognition of linguistic pluralism would, in many polities, alert us to the possibility of a significant break from a longstanding language policy pathway. Additionally, the global political climate has changed considerably in the last two decades and it has become increasingly less hospitable to the recognition and accommodation of diversity and, consequently, to a necessary condition for the implementation of multilingual governance. In a short period of time, immigrant-receiving countries have witnessed a “backlash” against new waves of immigration (see Vertovec and Wessendorf Reference Vertovec and Wessendorf2010) and anti-diversity and mono-cultural populist movements have gained mainstream electoral success (see Chin Reference Chin2017). Given these developments, the implementation of multilingual governance techniques at the domestic level since the onset of COVID-19 may then also suggest that the pandemic is reversing what is effectively a global trend towards cultural and linguistic monism.

IV. Multilingual Governance in the United States: A Case Study

This article focuses more specifically on multilingual governance in the United States. Due to its federal structure, the United States provides the possibility to test for both observable implications of the COVID-19 critical juncture hypothesis. The United States is also a linguistically diverse country. According to recent census data, nearly 68 million American citizens speak a language other than English at home, and roughly 25 million citizens speak English less than “very well” (US Census Bureau 2019). Despite this deep linguistic diversity, the United States long adhered to a model of “Anglo-conformity” (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka2001, 154) that emphasized cultural and linguistic assimilation. While this began to change in the 1960s, language policy in the form of both multilingual and monolingual governance has followed complex trajectories at both federal and state levels leading up to and following the pandemic’s onset.

At the federal level, government agencies and departments first implemented multilingual governance after President Bill Clinton issued Executive Order 13166. The order enforces Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and, in particular, its prohibition against discrimination on the basis of national origin. More specifically, Executive Order 13166 “requires Federal agencies to examine the services they provide, identify any need for services to those with limited English proficiency (LEP), and develop and implement a system to provide those services so LEP persons can have meaningful access to them” (Executive Order 13166, 2000). Each federal agency has developed a Limited English Proficiency plan (which is referred to either as an LEP plan or as a Language Access Plan, LAP) in compliance with Executive Order 13166.Footnote 2

This has, however, taken place against the backdrop of an institutional stalemate regarding official multilingualism. Between 1980 and 2021 (see Tremblay Reference Tremblay2019; Tremblay Reference Tremblay2021), members of Congress introduced roughly 113 “official English” bills, many of which have proposed to entrench monolingual governance at the federal level in some form or another. However, none of these bills has made it to the final stages of legislative enactment. More relevant to this article is that a much smaller movement seeking to pass “English Plus” legislation that would both affirm English as an official language and promote the importance of multilingualism has been equally unsuccessful (Tremblay Reference Tremblay2019, 174–75). Overall, the “English Plus” movement has garnered far less support than the “official English” one in the federal legislature.

At the state level, language policy has followed a somewhat different trajectory. Here, the so-called “official English movement” has been far more effective. By 2020, thirty states had declared English as their official languageFootnote 3; some states did so through an amendment to their state constitution, while English has been made the official language in other states through the enactment of “official English” laws. To be sure, there is debate over the impact of official English. On the one hand, Tatalovich (Reference Tatalovich1995) argues that “official English” legislation is largely symbolic. Faingold (Reference Faingold2012, 139), on the other hand, develops a classification of states with language policies which shows that the majority of “official English” states do not offer legal protections for minority languages and that they additionally “establish language provisions to protect the official language.”Footnote 4

Overall, there is significant public support for “official English” policies in the United States. These policies cut across ideological positions (see Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2005) and they are, for many Americans, rooted in “an attachment to a traditional image of Americanism” (Citrin et al. Reference Citrin, Reingold, Walters and Green1990, 536). To be sure, a handful of states (New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, Washington) have adopted non-binding “English Plus” resolutions to “not declare English as their official language and, concomitantly, to promote second language acquisition” (Tremblay Reference Tremblay2019, 180–81, emphasis in original) and two “official English” states officially recognize and protect a language other than English.Footnote 5

Since the onset of the pandemic there have been new developments in multilingual governance at both the federal and state levels. At the federal level, the websites for Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—the two federal agencies most directly responsible for the government’s pandemic response—offer COVID-19 health and sanitary information in a range of languages. The FEMA webpage detailing the agency’s “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Response” (Federal Emergency Management Agency, n.d.) provides links to translated webpages in Spanish (e.g., Respuesta por Coronavirus (COVID-19)) and in Haitian Creole (e.g., Entèvansyon parapò ak Coronavirus (COVID-19)). The CDC website offers more materials in languages other than English. The CDC website’s main page provides an Español link that, when clicked, transfers the user to the Spanish-language version of the CDC website (i.e., Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades CDC).Footnote 6 It also provides a link to “other languages” that, when clicked, transfers the users to a webpage with “CDC Resources in Languages Other than English.” On this webpage, there are links to Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese portals on “COVID-19 web information” as well as to the CDC en Español website. One can also find on this page a “Communication Toolkit for Migrants, Refugees and Other Limited-English-Proficient Populations” through which one can access all of the CDC’s seventy-two print resources on COVID-19, eighteen of which have been made available in languages other than English.Footnote 7

At the state level, developments in multilingual governance are striking. Since the onset of the pandemic, the health department websites in ten “official-English” states have installed translation tools (i.e., translation widgets) and now deliver health information and health services in languages other than English. These ten states are listed in Table I below.

Table I “Official English” States Offering Multilingual Services

The implementation of multilingual responses to COVID-19 at both federal and state levels provides an opportunity to test for one of the observable implications of the critical juncture hypothesis. Developments at the federal level allow for a test of the “radical institutional change” implication. At the federal level, evidence that the implementation of online multilingual governance by FEMA and the CDC was directly driven by legislative changes—thus upending a longstanding institutional stalemate—would support the critical juncture hypothesis. By contrast, evidence that FEMA and the CDC updated or expanded their Limited English Proficiency Plans following the pandemic, in the absence of any relevant legislative change, would infirm the hypothesis and suggest the possibility that COVID-19 is simply accelerating a pre-pandemic policy pathway initiated by Executive Order 13166.

State level developments allow for a test of the “turning point” implication. If no other state health departments in the twenty other “official English” states implemented multilingual governance prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, then this would mean that the ten states listed in Table I are evidence of an abrupt departure from a state-level monolingual trajectory. If, on the other hand, there is evidence that state health departments in other “official English” states not listed in Table I implemented multilingualism before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, then this would infirm the hypothesis. This evidence might also suggest the existence of a heretofore overlooked pre-pandemic multilingual governance trajectory at the sub-state level.

V. Testing the Critical Juncture Hypothesis

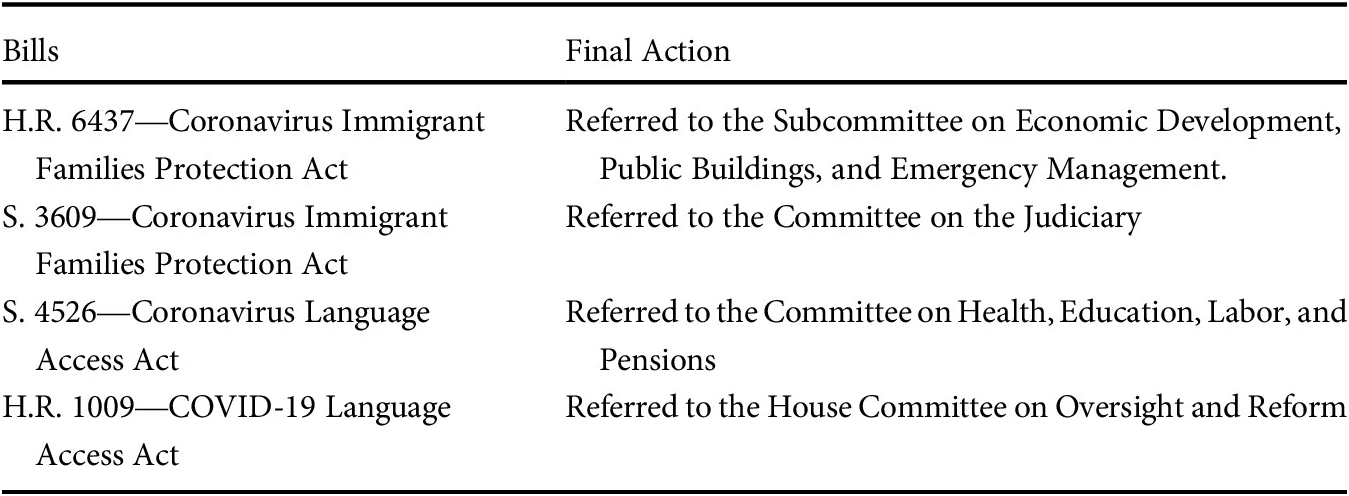

What does the evidence tell us? During the 116th Congress (3 January 2019 to 3 January 2021), members of Congress introduced three bills advancing multilingualism in the delivery of public health services related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Two of the bills—US HR 6437 and US S 3609—were titled Coronavirus Immigrant Families Protection Act and had nearly identical texts. These bills sought: “To ensure that all communities have access to urgently needed COVID-19 testing, treatment, public health information, and relief benefits regardless of immigration status or limited English proficiency, and for other purposes.” Their main multilingual provisions were covered under Section 5 (“Language Access and Public Outreach for Public Health”). This section outlined a new mandate for the Director of the CDC. It would require, upon enactment, that the Director provide grants to and fund cooperative agreements with community-based organizations to support “culturally and linguistically appropriate preparedness, response, and recovery activities” (Sec. 5.a.1). The Director would also be required to ensure that materials on “screening, testing, and treatment for COVID-19” are disseminated in languages covered by FEMA’s LAP (Sec. 5.b.1) and to establish an “informational hotline” also accessible in these languages (Sec. 5.c).

The bills also included a provision under Section 6 (“Access to Support Measures for Vulnerable Community”) that any federal agency receiving funding as a result of a Coronavirus response law (e.g., the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act) would be required to translate materials for programs and opportunities in languages covered under FEMA’s LAP. Both bills contained clauses for appropriations in the amount of 100 million dollars and required that no less than half of the sum be spent on funding grants and establishing cooperative agreements (Sec. 5.e.1 in both bills).

A third bill advancing multilingual governance that was introduced during the 116th Congress—US S 4526, the Coronavirus Language Access Act—included all of the provisions listed above. In addition, this bill included a mandate for the Secretary of Health and Human Services, acting through the Director of the CDC, to award grants and enter into cooperative agreements with community-based organisations, as well as with state-level health departments, to support the dissemination of materials on COVID-19 sanitary measures in so-called “priority languages” (Title 1, Sec. 102.a.1.A). This would mean the provision of these materials in “at a minimum, the 15 languages spoken with greatest frequency by individuals with limited English proficiency in that State” (Sec. 2.5.B). The bill also authorized 200 million dollars in appropriations of which no less than three-quarters would be spent on funding grants and cooperative agreements (Title 1, Sec. 102.e).

Just over a week into the next congress’s first session (i.e., the 117th congress lasting from 3 January 2021 to 3 January 2023), Representative Grace Meng (D-NY-6) introduced an abridged version of the COVID-19 Language Access Act (as H.R. 1009). The bill required any Federal agency receiving COVID-19 financial assistance to translate written materials pertaining to the “pandemic, including COVID–19 vaccine distribution and education” (Sec. 2) no later than seven days after the publication of these materials in English. This would mean the translation of documents into at least twenty minority languages: Arabic, Cambodian, Chinese, French, Greek, Haitian Creole, Hindi, Hmong, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Laotian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, Thai, Urdu, Vietnamese….

As we can see in Table II, none of the bills described above made it past the committee stage of the legislative process. This means that the pre-pandemic institutional stalemate over the language of federal government has persisted. This also means that the implementation of multilingual governance in the FEMA and CDC websites can likely be attributed to their respective LAPs. The CDC’s limited English proficiency guidelines are covered under the ambit of the 2013 LAP for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). It requires that all HHS agencies “highlight the availability of consumer-oriented materials in plain language and languages other than English on Department websites and ensure such materials inform individuals with LEP about available language assistance services” (Department of Health and Human Services 2013, 13). The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s 2016 LAP, for its part, highlights the continuing efforts of the agency’s Office of External Affairs to develop multilingual web resources in response to disasters (US Department of Homeland Security 2016, 22). In brief, the implementation of COVID-19 multilingual techniques in these two websites was not preceded by radical institutional change and can be traced back in both cases to Executive Order 13166.

Table II The Fate of Multilingual Governance Legislation (116th and 117th Congresses)

Evidence from the state level can further infirm the COVID-19 critical juncture hypothesis. Table III categorizes all fifty state-level health department websites as either monolingual or multilingual. Monolingual health department websites are those that offer public health information and access to health services in English only. Multilingual health department websites are those that offer public health information or access to health services, or both, in English and at least one other language. Unlike a recent (see Kusters et al. Reference Kusters, Gutierrez, Dean, Sommer and Klyueva2022) study of health department websites in six major American cities, it is beyond the scope of the present study to distinguish between the types or the quality of multilingual services offered at the state level; the focus here is simply on whether or not these services are offered.Footnote 8 As one can see in Table III, the vast majority of state-level health department websites have implemented some form or other of multilingual governance.

Table III Monolingual and Multilingual State Health Department Websites

The data is further broken down in Table IV. This table shows which of the forty-two state-level health department websites implemented multilingual governance prior to a state’s official proclamation of a state of emergency in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 9 According to the table, twenty-five state health departments that have implemented multilingual governance techniques did so prior to a proclamation of a state of emergency related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table IV When did State Health Department Websites Implement Multilingual Governance?

Table V examines a subset of state health departments that implemented multilingualism: states that also made English their official language. The data in Table V is striking for two reasons. First, it shows that multilingual governance has even taken hold in contexts where a state has adopted a formal recognition of only one language. Second, it shows that more than half (i.e., 58 percent) of “official English” states that implemented multilingualism in the delivery of health services did so prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table V When did Health Department Websites in Official English States Implement Multilingual Governance?

* Reliable data is only available for 23 states.

In sum, the evidence presented above shows not only that a majority of state health department websites that implemented multilingual governance techniques did so before the COVID-19 pandemic’s onset but that a majority of health department websites in “official English” states did so too. Consequently, the implementation of multilingual governance techniques by “official English” states following the onset of the pandemic cannot be viewed as truly and uncontestably innovative, and nor then can the COVID-19 pandemic be seen as a key turning point in the implementation of multilingual governance techniques at the state level.

VI. Discussion and Conclusion

If COVID-19 is not a critical juncture, could it possibly be a path-clearing event? The evidence presented in the foregoing sections should also give us pause for thought about automatically confirming an alternative path-clearing accelerator hypothesis. For one, fifty percent of all states implemented multilingual governance techniques before the pandemic’s onset. Consequently, it is difficult to argue that the pandemic sped up “event sequences along the pathway.” Additionally, it is not clear whether the pandemic was critical in “allowing policy choices which would have been otherwise more difficult to make occur.” If the pandemic was indeed path-clearing, one might have expected state health departments to have implemented multilingual governance techniques after Google made it less difficult to offer translation services by making its Google Translate Website Translator available free of charge for “government, non-profit, and/or non-commercial websites” (Google Search Central Blog 2020) in May 2020. What is striking is that thirty-two state health departments—including twenty-two in “official English” states—implemented the Google “widget” before May 2020 and, in some cases, well before the pandemic’s onset. In other words, these state health departments made the choice to implement multilingual governance techniques when it was (at least technically) more difficult to do so.

The foregoing discussion raises another possibility: could it be that the implementation of multilingual governance techniques during the pandemic is evidence of subtle and gradual institutional change? There is some preliminary evidence to support this hypothesis. Since no “official English” state has repealed its formal commitment to monolingualism, the implementation of multilingual governance in the delivery of health services and health information in these states would seem to have been “layered” onto the existing institutional framework. The process of “layering” is evidence of a subtle and gradual institutional change that entails “attachment of new institutions or rules onto or alongside the existing ones” (Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010, 20); it is distinct from institutional displacement, a rapid and dramatic form of change, that would have meant—in the present case—a shift towards official multilingualism. A full evaluation of this hypothesis would, however, require testing for two additional observable implications: that the existing institutional framework is open only to “a low level of discretion in interpretation” (ibid., 19) and that the political context affords defenders of the status quo with “strong veto possibilities” (ibid.). Testing for these two implications may be something to consider for future research.

There remains yet another possibility: the implementation of multilingual governance techniques might be evidence of the reinforcement of a policy pathway initiated well before the pandemic. If this is indeed the case, then what we might be observing are the lasting effects of what John D. Skrentny (Reference Skrentny2004) refers to as the American “minority rights revolution.” This rights revolution, according to Skrentny, lasted from 1965 to 1975 and emerged in the wake of Civil Rights mobilization and the enshrinement of the Civil Rights Act 1964 and against the backdrop of the United States’ competition with the Soviet Union over global moral supremacy. The “minority rights revolution” is therefore a distinct and characteristic phenomenon of the mid to late twentieth century. Its main participants were legislators and civil servants who—sometimes acting as what Skrentny terms “meaning entrepreneurs” (ibid., 11)—employed a logic of appropriateness in extending a rights framework initially designed for African Americans in attempts to redress inequalities for other minority groups. While the “minority rights revolution” led to major institutional changes (for example: the Voting Rights Act 1965, the Bilingual Education Act 1968, and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973), it also formed the basis for modern American “identity politics” (ibid., v) that advocates minority group recognition and group representation. In the context of the present discussion, the implementation of multilingual governance techniques might simply be an indication of the salience of identity politics in federal and state-level public administrations and the continued use by civil servants of a logic of appropriateness grounded in normative ideals of equality, fairness, and justice. At a more speculative level, this may also indicate the continuing relevance—in a context that by all appearances is increasingly inhospitable to the recognition of diversity—of the cross-national adoption of multiculturalism policies and enshrinement of minority rights during the latter half of the twentieth century.

Overall, this article’s findings infirm the COVID-19 critical juncture hypothesis but, admittedly, cannot confirm alternate explanations. That being said, they do offer two preliminary recommendations for the study of the global pandemic moving forward. First, they caution against unquestioningly assuming that the COVID-19 pandemic is leading (or will lead) to radical institutional change and that it is in and of itself driving the development of new or innovative governance techniques. Second, they point to the importance of balancing a focus on the present with an understanding of the past, for if we look too closely at the pandemic as the proximate cause of recent developments, we may actually wind up overlooking the longer-term effects of other—and perhaps far more important—transformative moments in human history.