Introduction

Political clientelism has been traditionally defined as the distribution of selective benefits to individuals or groups in exchange for political support (Katz, Reference Mair and van Biezen1986; Hopkin Reference Katz2001, Reference La Raja2006b; Piattoni, Reference Scott2001; Kitschelt and Wilkinson, 2007). Earlier studies have shown that many contemporary clientelistic linkages take the form of a pyramid structure. This assumes the existence of exchanges between patrons (parties) and clients (voters) with the help of brokers (party organizations). In this scheme, the exchange takes the form of resource allocation or access (from parties to voters) and of electoral support (from voters to parties). Although useful, this structure raises two troubling questions. The first is a theoretical concern and refers to its one-dimensional character. While aimed to enhance electoral mobilization, clientelism relies on resources that have been treated until now as endogenous to the political system. Second, it is unclear what happens in those settings where brokers have low capacity because party membership organizations are minimal.

This article tries to provide an answer to both questions by proposing a bi-dimensional model of clientelism that emphasizes the role of exogenous resources. The vertical linkage between political parties and electorate is complemented by a horizontal nexus between parties and private contributors (economic agents). In an environment characterized by low internal resources, parties involve external actors to get the necessary money. The central argument of this new model is that public resources are no longer used in relationship with the electorate, but with private campaign donors. The latter benefit from public procurement procedures and supply financial support to political parties. To illustrate how this mechanism works we focus on Romania between 2008 and 2012, a crucial case for the study of clientelism due to the high number of references to this process in the media and international reports. Our empirical study uses qualitative content analysis of official public records, media reports, and legislation regarding private donations and public procurement. Party histories and secondary data are also used to assess the extent of membership organizations.

The major contribution brought by our paper to the existing literature lies in the identification of a new analytical layer. By exploring the link between political parties and economic actors, the bi-dimensional clientelistic model explains how a new category of client emerges and how this linkage reinforces the mechanism of classic clientelism through redistribution of resources. Thus, unlike earlier studies that accounted for a systemic explanation of the perpetuation of clientelism, our analysis brings into the picture the resources outside the political system. Still, the mechanism presented in this article is not the mere reflection of private campaign financing, corrupt practices, and traditional approaches of intertwinement between politicians and private donors. Instead, it emphasizes a paradigm shift in how clientelistic parties focus on resource accumulation for political consolidation.

The following section reviews the literature on clientelism and criticizes the shortcomings of the pyramid structure. Next, we briefly discuss the issue of private funding and emphasize the elements favoring a close connection between private contributors and political parties. The third section presents, in detail, the new model of clientelism and explains its theoretical mechanisms. The fourth section brings empirical evidence from the Romanian case to illustrate how this new model functions in real life. The conclusions summarize the main findings and discuss the implications of our analysis.

The clientelistic phenomenon: structural changes and adaptation

The studies concerned with the clientelistic phenomenon can be seen as having a similar evolution with the changes and adaptations of the clientelistic manifestations themselves. Most of the relevant literature is structured around the model of exchanges between a patron and a client, but there are significant variations in how this relationship is further framed and contextualized across different countries and political settings. As such, most of the first comprehensive studies on this topic looked at clientelistic exchanges either as a phenomenon embedded in the political practice (Weingrod, Reference Weingrod1968; Scott, Reference Szczerbiak1972), or as a broader cultural and societal issue (Gellner and Waterbury, Reference Graziano1977; Eisenstadt and Roniger, Reference Eisenstadt and Roniger1984).

Given the opportunity of regime change in many of the most frequently covered cases of clientelism spread across Latin America and Southern Europe, the literature gradually focused on the connection between political transformation and the adaptive reactions of agents involved in clientelistic practices (Lyrintzis, Reference Neumann1984; Hopkin and Mastrapole, Reference Hopkin2001; Caciagli, Reference Chubb2006; Golden and Picci, 2008). Consequently, political scientists were able to provide much more of a structured perspective on this phenomenon, linking the participants within coherent schemes of electoral mobilization (Piattoni, Reference Scott2001; Hopkin, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2006a; Kitschelt and Wilkinson, 2007).

From very early on, the literature has revealed the concept of machine politics and the corrupt connections with business groups and private interests (Graziano, Reference Katz1978; Chubb, Reference Fisher1981, Reference Ferejohn1983; Stokes, Reference Volintiru2005). While in practice we often see pervasive corruption as intrinsically connected to clientelistic networks, the two should be treated separately from a theoretical point of view. This disentanglement of clientelistic transactions and corruption is useful in distinguishing the structural changes suffered by the clientelistic system itself. In this sense, given its network deployment, political relevance and consequence, and interpersonal normative function, clientelism presents a wealth of avenues to explore and assess. In this sense, our assessment of the political parties’ reliance on public contractors directly addresses the aforementioned lineage in the existing literature, which targets the clientelistic phenomenon.

The pyramid structure and its shortcomings

Given this phenomenon’s survival and entrenchment within the context of democratic politics, clientelism can be analyzed as a multi-layered system, with complex structures. Gradually, the dyadic ties evolve into a more ‘complex pyramid exchange network of client-broker-patron exchange’ (Kitschelt and Wilkinson, 2007: 8). Clientelism becomes the object of market exchanges between supply provided by the political parties and candidates, on one side, and the demand of clients willing to exchange their votes for goods and favors, on the other side. Within this approach, the clients’ leverage is high as they are no longer forced into a relationship of asymmetrical power but are voluntary participants in a transaction (Hopkin, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2006a). In other words, ‘democracy strengthens the clients’ bargaining leverage vis-à-vis brokers and patrons’ (Piattoni, Reference Scott2001).

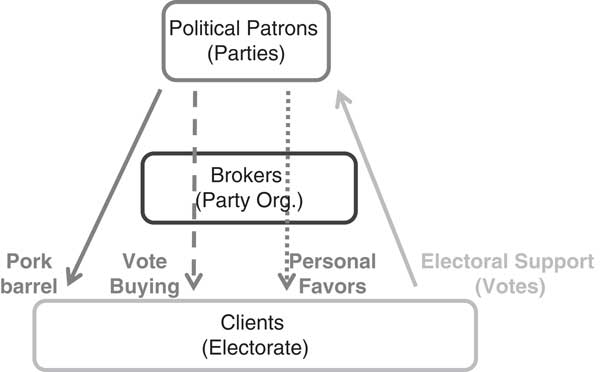

Following these developments, clientelism can be visualized in the form of a pyramid structure with clients at the base, brokers in the middle and suppliers at the top. Referring to politics, this pyramid approach includes three categories of participants: (1) the electorate (clients) as a general group, and the party supporters or voters, as specific groups of beneficiaries, (2) party organizations (brokers) including members or local leaders acting as intermediaries between the electorate and the supply side, and (3) political leaders or parties in the central office (patrons) able to control and distribute goods and services to the clients (Figure 1). The ‘broker-mediated distribution’ (Stokes et al., Reference Van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2013) is probably the most important addition to the clientelistic phenomenon in the transition from personal patronage to the new large scale, electorally driven system.

Figure 1 The pyramid clientelistic structure.

Second, there are the vote-buying strategies in which money and goods are offered – during the electoral campaign or Election Day – usually on a non-iterative basis. Brokers are necessary intermediaries, but their influence is considerably diminished compared with the previous case of personal favors, because they are no longer required to provide the functions of selection and oversight. Furthermore, the clients can be both the loyal supporters and the undecided voters. Stokes et al. (Reference Van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2013) bring evidence to show that loyal supporters are usually the target of non-iterative exchanges from parties. Gherghina (Reference Hopkin2013) illustrates that, in addition to targeting their own supporters, parties use vote-buying strategies to persuade the undecided. As a result, it is not so much about persuading votes, as much as mobilizing turnout.

Third, there is a formal exchange of targeted public spending in return for political support. This process of channeling public resources or material benefits to selected districts, or particular categories of voters, is generally referred to as pork-barrel spending (Ferejohn, Reference Gherghina1974; Shepsle and Weingast, Reference Von Beyme1994; Case, Reference Doroftei and Dimulescu2001; Calvo and Murrilo, Reference Calvo and Murillo2004; Ashworth and de Mesquita, Reference Ashworth and de Mesquita2006; Stokes et al., Reference Van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2013). While serving to strengthen the electoral support for the ruling party, pork-barrel politics follows, to a certain extent, the logic of programmatic mechanisms and, as such, it is a formal process of rewarding loyal supporters that bypasses the party organizations. Examples include targeting spending on wages or pensions for certain categories of people, or localized programs of infrastructure development.

In spite of its useful structuring of linkages, this pyramid conceptualization of clientelism has several flaws. To begin with, it assumes that all selectively distributed goods and services are public resources controlled by the political patron and deployed according to an electoral strategy of survival. This assumption is problematic for two reasons: (1) certain favors such as public contracts usually require more than just political support in exchange, and (2) to control substantial resources, patrons need electoral victories; this leads to a vicious circle in which only ruling parties can employ clientelistic practices. While the first assumption will be addressed by the present research, the latter has already been contradicted by evidence from earlier studies, showing that it is not only the ruling parties that deploy clientelistic tactics (Piattoni, Reference Scott2001; Schaffer, Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Busco2007; Volintiru, 2012; Gherghina, Reference Hopkin2013).

Furthermore, the pyramid structure assumes the existence of an effective territorial deployment of party organizational capacity. Accordingly, it takes for granted the existence of brokers (i.e. intermediary level) in the clientelistic pyramid. Since party membership is shrinking in many West European countries (Mair and van Biezen, 2001; van Biezen et al., Reference Van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012) and has been minimal in Eastern Europe (Webb and White, Reference Williams2007; Lewis, Reference Nassmacher2008), one can easily argue that political parties face significant challenges in terms of their brokering capacity. Consequently, their capacity to engage in several clientelistic linkages is fairly limited.

In light of these shortcomings, we argue that clientelism can be better understood – at least in Eastern Europe – as a composite of horizontal and vertical linkages. In doing so, we bring the role of private donors into the picture whose resources can be traced to public procurement contracts. While the issue of private party financing has been extensively discussed in the literature, to our knowledge there is no prior linkage with the clientelistic system of resource distribution.

Private funding becomes important when vote buying prevails over the other two forms of clientelistic exchanges, that is, personal favors and pork-barrel. This happens because the latter rely more on state resources, while vote buying can make efficient use of private contributions. While we do not expect vote-buying to be the most determinant clientelistic electoral strategy employed by a political party, as it is usually complemented by other tools, we explore in detail this exchange system in which liquidity plays the major role.

In our model, state resources are not used to reach the clients (as in the pyramid structure) but are directed towards private contractors in exchange for money. Furthermore, the analysis of private donations is a proxy assessment of the informal exchange mechanisms that occur within this horizontal linkage system. Vote buying is more frequently financed through non-declared income, but we suspect it is derived through the same mechanisms. The following section explains in detail how private funding creates the nexus with political parties in our modified model of political clientelism.

The nexus with private funding

Almost one century ago political parties were considered the pillars of representative democracies (Bryce, Reference Chubb1921; Schattschneider, Reference Stratmann1942). Since then, their importance remained unchanged but their functions diversified. Parties are the transmission belt between society and the state being the channel through which individuals and groups in society are integrated into the political system. Parties articulate, aggregate and represent interests, mobilizing the general public during elections (van Biezen and Kopecky, Reference Van Biezen and Kopecky2007; Katz, Reference Lyrintzis2011). Since politics consists of complex and sophisticated processes, the choice among initial alternatives is not often accessible to ordinary voters. Parties simplify choices and generate symbols of identification and loyalty (Neumann, 1956; Dalton and Wattenberg, Reference Flickinger and Studlar2000). Following elections, parties are essential for government through political decisions and implementation, that is, policy-making. To fulfill these functions and exercise their core activities, parties need substantial resources.

Costs related to administration and election campaigns are high – and have increased over time – and parties use a mix of private and public sources of income. Since internal party funding (e.g. membership fees, profits of party-owned businesses) is fairly limited, political parties have to rely on external means of financing such as contributions or donations from private individuals and companies.Footnote 1 In this context, the major risk lies in the misuse of these resources to influence specific political decisions. Earlier studies identified the existence of a causal relationship between campaign contributions and policy outcomes but found it difficult to pinpoint the drivers behind the effect, for example politicians’ ideology, particular favors, or specific types of contributors (Chappell, Reference Ewing1982; Snyder, Reference Van Biezen1990; Stratmann, Reference Webb and White1995; Ansolabehere et al., Reference Ashworth and de Mesquita2004). To partly diminish these risks and to ensure multi-party competition, many countries in Europe have adopted regulations on public funding. These provisions bring some disadvantages since public money may lead to dependence on the state and inhibit parties’ connections with the electorate (van Biezen, Reference Van Biezen2004). Under these circumstances, private finances can be healthy for a political system if it is strictly regulated to allow for transparency (of revenues and expenditures) and if there is a balance between the two types of funding.

The debate on private funding has been built around three inter-connected topics: illicit contributions, inequalities, and corruption. First, the illicit contributions refer to the private donations that contravene existing laws of political financing. Illegal donations cast major doubts on the morality of the political competitors accepting them and often translate into non-transparent handling (La Raja, 2008). There are rare instances in which political parties keep reliable records of private contributions and often avoid or falsify public disclosure. Consequently, illicit donations are considered scandalous independent of their effect. This is the case even when the contributor does not expect any benefit in return for the donation (Pinto-Duschinsky, Reference Shepsle and Weingast2002) especially if the donors are contested sources such as mafias or drug cartels (Freidenberg and Levitsky, Reference Gray and Caul2006). Second, private resources often lead to unequal competition for public office. Political parties or candidates with wealthy supporters are in a better position than their competitors. They can spend more in electoral campaigns, increase their visibility, reach more voters and thus gain greater political influence (Ewing, Reference Gherghina1992; Johnston and Pattie, Reference Lewis1995; Fisher, Reference Gherghina and Soare2002).

Third, and by far the most discussed problem associated with private funding, there is a risk of corruption. Although a contested concept, corruption essentially rests on the distinction between formal obligations to pursue the public good and behaviors or practices that undermine the public good. Corruption takes several forms when private funding is involved and they can refer either to sources or to mechanisms through which political decisions are influenced and distorted. To begin with the sources, one of the most obvious situations is the use of money originating from corrupt transactions. In this case the donation may not be illicit, but remains highly problematic because the receiving party overlooks misconduct of the donor. Related to the latter, corruption scandals surround the acceptance of money from disreputable sources (Pinto-Duschinsky, Reference Shepsle and Weingast2002). Apart from the overlap with their illicit character (see above), tainted donors are usually associated with tainted practices by the electorate and media.

Moving on to the mechanisms, private money often comes with strings attached. Contributors and parties are likely to enter a relationship of reciprocity in which money is offered in exchange for specific political decisions. In extreme situations, when the sponsorship is high, the party is effectively bought and abandons its initial purposes. As a result, it delivers policies to the donors and partly or completely fails in delivering them to society (Nassmacher, 1993; Williams, Reference Williams2000). Simply put, political parties make use of state resources to favor or to promise favors to their benefactors. The corrupt practices also include spending for unfair or illegal purposes such as vote-buying. Parties provide voters with gifts of various kinds (see the empirical section of this article) aiming at securing their electoral support. Empirical evidence shows that, in recent years, vote-buying remains a component of many election campaigns around the world. While in theory the usual suspects are the impoverished countries where ‘the politics of the belly’ prevails, vote-buying occurs in countries with various degrees of economic development and democracy (Pinto-Duschinsky, Reference Shepsle and Weingast2002; Brusco et al., Reference Chappell2004; Schaffer, Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Busco2007; Bratton, Reference Cassel and Luskin2008).

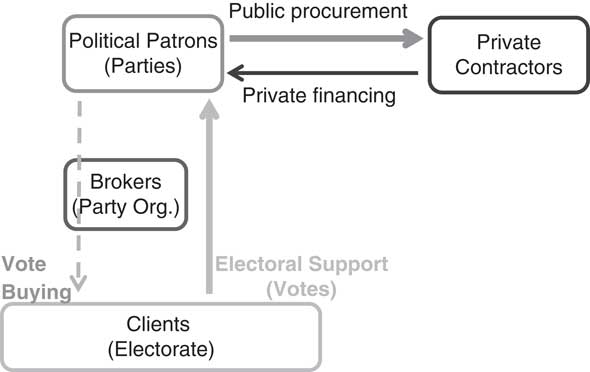

The policy distortion and illegal spending fueled by private financing lie at the core of the horizontal linkage in our model (Figure 2). In this respect, political parties make massive use of private contributions to buy electoral support. In doing so, they do not allocate state resources to directly buy votes but channel them towards the private contractors as rewards for their generous contributions. The horizontal clientelistic loop created between parties and private donors is reinforced by their mutual benefits: the former retain power, while the latter increase their economic profits.

Figure 2 The bi-dimensional clientelistic structure.

A new model of clientelism

As previously explained, the new model of clientelism works best when the resource allocation is narrowed to one major strategy, that is, vote-buying. These are the circumstances under which the involvement of private contributors brings large benefits to parties, that is, more money to buy electoral support. These two changes lead to a bi-dimensional clientelistic structure (Figure 2) with two types of exchanges: vertical (between parties and voters) and horizontal (between parties and private contractors).

One characteristic of this model is the minor role played by brokers, which leads to fewer clientelist means being used to reach the electorate. This is consistent with the empirical realities of the most recent decades in which party membership has decreased considerably. Small party organizations mean few available brokers and, thus, a large-scale distribution of personal favors is unlikely to happen. At the same time, in the context of a decreasing turnout (Cassel and Luskin, Reference Eisenstadt and Roniger1988; Flickinger and Studlar, Reference Golden and Picci1992; Gray and Caul, Reference Johnston and Pattie2000) the strategy of continuously fueling the loyal voters through personal favors becomes less effective that the one-off exchanges in the electoral periods, such as vote-buying. In brief, both dimensions of decreasing participation – involvement in parties and voting – determine a shift in the clientelistic paradigm. The discretionary distribution of benefits is partly deprived of party brokers and permanent clients. As such, it becomes significantly more focused on accumulating resources, and deploying such funds within the specific electoral periods.

Another characteristic is the limited role of pork-barrel. It is an effective mean of mobilizing the electorate both by distributing benefits and by showing loyalty to the electoral base. In addition, it is entirely legal if not necessarily legitimate, to support the interests of the party voters more intensely than those of the rest of the electorate. In spite of these advantages, it is less used in comparison with other clientelistic strategies for at least two reasons. First, it is costly and thus harder to use in an environment of budgetary constraints. Second, it is limited to the relationship between the ruling party and core voters and thus not helpful in mobilizing undecided voters.

Following these changes, the strategy of vote-buying becomes the key element for resource distribution. Its efficiency does not rely on pyramid informal structures maintained over time but on the level of allocated resources. It bypasses the selection and oversight functions of the long-term clientelistic linkages. Reversely, it is particularly conditioned by the patrons’ availability of resources. This creates the need of the clientelistic system to extend its mechanisms of resource accumulation. This is the moment when private contractors become vectors of resource accumulation in the clientelistic scheme. In light of the potential profit they can make, private contractors working on public contracts are likely to be highly involved in the horizontal linkage depicted in Figure 2. They engage in a closed circuit with political patrons exchanging private funds for public resources. Private contractors receive public funds through public procurement contracts, which lead back to the political parties in government through legal private donations. While this exchange may involve secondary processes (e.g. illegal donations) it sheds light on preferential resource allocations and indicates that the accumulation of resources is a priority for political parties. These contractors lack incentives to target electoral mobilization (clients) or to enhance party organizations (brokers) and that is why they are unlikely to engage in horizontal clientelism. With one exception, the situation in which private contractors electorally mobilize their employees, there is a clear distinction between horizontal and vertical clientelism: one is mobilizing resources, and the other is mobilizing voters.

Through the development of a horizontal layer, the clientelistic system is not only a principal vehicle of electoral mobilization, but also one of resource accumulation. It no longer serves as a continuous platform of patronage, but works as a ‘buy-off’ system limited in time and value. This new survival strategy provides two advantages for political parties. First, the clientelistic networks are more easily manageable as they comprise fewer participants, clearly separated. On the horizontal linkage, the interactions usually involve political patrons and private contractors. On the vertical linkage, the structure includes patrons, brokers, and clients, but it is much narrower than in the pyramid structure. Second, this clientelistic arrangement allows more resources to be accumulated by the patrons. Accordingly, it ensures the convergence of party elites’ interests and thus improves the possibilities of remaining in power. In the background of a general party cartelization tendency, political parties can become even further intertwined as they benefit from the same distributional paths.

In contrast, the electorate loses. While the pyramid clientelistic model brings some benefits to the clients through the preferential distribution of public resources, the bi-dimensional clientelistic system deprives voters of their share of public resources; it goes instead to private contractors. In this new setting, the clientelistic linkages have also an exploitative function in addition to that of electoral mobilization. The importance of electoral competition is matched by resource accumulation and they reinforce each other.

So far, we have built a theoretical model of clientelism that will better capture the types of exchanges in which political parties may engage in contemporary times. To show how it works we use the case study of Romania between 2008 and 2012 (the most recent legislative elections). This is the most likely case where the new model of clientelism can be observed. As illustrated in the following section, Romanian politics has features of cartelization, the parties have small organizations, and there is extensive evidence of vote-buying. All these features contribute to the emergence of a solid horizontal linkage between parties and private contractors.

The functioning of bi-dimensional clientelism

This section starts with a brief presentation of the features of Romanian parties in terms of cartelization of politics and limited membership organization. The second sub-section gives evidence of vertical clientelism, while the third presents in detail the horizontal linkage.

Cartelization of politics and membership organizations

Until the legislative elections of December 2012, Romania was the only East European country where no new political parties have entered the parliamentary arena for two decades.Footnote 2 Since 1992, only a handful of political competitors have secured parliamentary seats and thus participated in coalition governments. Among these parties, some failed to gain parliamentary seats and have never managed to return to the legislature since then, for example, the Christian Democratic National Peasants Party in 2000, the Greater Romania Party (PRM) in 2008. There were many failures of other political competitors to gain parliamentary representation, for example, the Alliance for Romania and the Union of Right Forces in 2000, the Socialist Alliance Party in consecutive elections, the New Generation Party (PNG) in 2004 and 2008, etc.

The four parties with a continuous presence in Parliament that have shaped the Romanian political scene over the last two decades are the Social Democratic Party (PSD), Democratic Liberal Party (PDL), National Liberal Party (PNL), and the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR).Footnote 3 These parties display inclusive coalition formation patterns in the sense that each party has joined a coalition with every other party. In addition, the elite is very homogenous and rarely changes: a large number of the members of Parliament are re-nominated and re-elected in consecutive terms (Stefan et al., Reference Van Biezen and Kopecky2012). Even when new parties emerge, like the case of the People’s Party Dan Diaconescu (PPDD), a part of the elite promoted to Parliament has belonged in the past to some of the major political parties (Gherghina and Soare, Reference Hopkin2013).

In addition to this cartelization of politics (Katz and Mair, 1995), the alternation in government makes every party subject to clientelism (both vertical and horizontal). A brief history of the electoral performance of the parties will provide a better understanding of their dynamics over the last two decades, in general, and of their situation in the two most recent elections in particular.

The PSD is a successor communist party, being the largest in the Romanian party system. Its origins go back to the 1992 split of the National Salvation Front (FSN), the winner of the 1990 elections. Following an internal dispute between the first two men from the party elite, the party split in two: the FDSN (later PDSR and PSD) and the FSN (later PD and PDL). Since its formation, the PSD won five out of six legislative elections and took part in four coalition governments (three times as the formateur). Since 2000, the party enjoys a stable electoral support situated around 33% of the votes.

The other successor party, the PDL, is the second largest party in Romania throughout the post-communist period. It came second in the 1996, 2004 (in two different electoral alliances), 2008, and 2012 legislative elections. It was part of three coalition governments, in one of them (2008–2012) as the main governing party. Unlike the PSD, the PDL is not characterized by constantly high electoral results across the entire post-communist period. Its electoral support oscillates with high levels of volatility.

The PNL is the third largest party in post-communist Romania. In the most recent legislative elections (2012), it formed an alliance with the PSD (the Social Liberal Union – USL), registering a landslide win. It has participated in two other coalition governments (1996 and 2004, once as the leading party). Its average share of votes is around 15% with a tendency to stabilize in the most recent decade. The UDMR has a very stable electorate and has enjoyed a pivotal role several times. It has participated four times in government coalitions, being a partner with each of the previous three parties. Apart from these four political parties, this analysis will also refer to the PPDD because it has engaged in clientelism to secure a position in the parliamentary arena. It came third in the 2012 elections (∼14% of the votes) but, soon after, the vast majority of its parliamentary elite left the party.

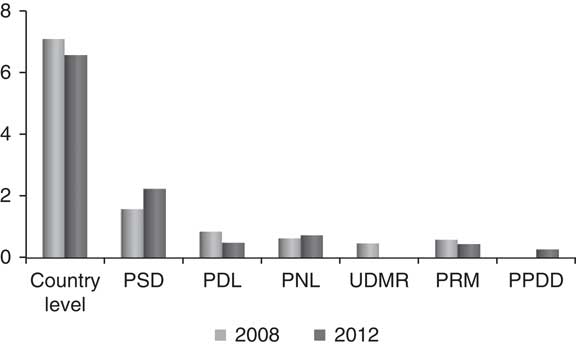

Let us now turn to membership organizations to see the extent to which patrons can rely on brokers for vertical clientelism. An extensive body of literature has illustrated that political parties in Eastern Europe have very small membership organizations (Mair and van Biezen, 2001; Szczerbiak, Reference Weingrod2001; van Biezen, Reference Van Biezen2003; Weldon, Reference Weldon2006; Spirova, Reference Van Biezen2007; Webb and White, Reference Williams2007; Lewis, Reference Nassmacher2008; van Biezen et al., Reference Van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012). In Romania, compared with other countries in the post-communist area, the percentage of members is quite high (Gherghina, 2014). This is partly due to election laws that require parties to have a few thousands members (variations between 10,000 and 25,000, depending on the law) to register in the electoral competition. Figure 3 depicts the evolution of membership percentages at country and party level in the 2008 and 2012 legislative elections.Footnote 4 With the exception of the PSD, the Romanian parties have membership organizations smaller than 1% in the electorate. Among these, the youngest party (PPDD) has <0.3%. In addition to these low levels, the PDL has lost members between the two elections. The same trend can be observed at country level. The PSD is the only party that has significantly augmented its membership organization from ∼1.6% to more than 2.2%.

Figure 3 Party membership as percentage in the electorate in Romania. Source: Official Party Registry in Romania (2012); Gherghina (2014).

These numbers indicate that Romanian political parties do not have strong membership organizations that would allow them to engage in multiple clientelistic linkages with the electorate. Although there is some variation in the size of membership organizations, none of the presented political parties developed strong organizations that allow them to pursue a broad range of clientelistic practices. Instead, these limited membership organizations reduce the spectrum of clientelistic exchanges to vote-buying and focus on cooperation with external actors to secure the necessary resources. Both issues are explored in the following sub-sections.

Vote-buying and private donations

This section focuses on the most popular three forms of vote-buying: (1) outright vote-buying, the payment of money from candidates or parties to the voters in return for votes; (2) treating, the provision of food or alcohol in exchange for votes but can also refer to feasts put on for voters; and (3) conveyance, the transport of voters to polling venues. Combinations between these three forms are likely to occur, for example conveyance is usually accompanied by outright vote-buying or treating. To show the incidence of vote-buying practices in Romania we use two sources: media reports and the official number of criminal case files registered at the High Court of Cassation and Justice (Romania’s Supreme Court of Justice).

The media reports were used to collect data on vote-buying in electoral campaigns and during Election Day for 2008–2012. We used the online and printed versions of five national daily newspapers, considered the most important in terms of subscribers: Adevarul, Cotidianul, Evenimentul zilei, Gandul, and Jurnalul National.Footnote 5 In addition to these newspapers, reports from the Romanian Press Agency (Mediafax) were also taken into consideration. Many articles included vote-buying allegations without substantial documentation. We have considered only those cases in which vote-buying was either well documented by journalists (i.e. interviews with bribe receivers, photos, or videos) or the situation ended up with a criminal case record. As a result, the final dataset includes a total number of 581 articles reporting on various types of vote-buying. The articles refer to 136 cases of vote-buying with considerable overlap in terms of coverage. Table 1 summarizes the vote-buying practices reported in the media indicating the number of practices and the county (territorial administrative division corresponding to constituencies in the previous PR list system) where they took place. Sometimes, more vote-buying activities occurred in the same county and that is why the number of practices does not always coincide with the number of counties in brackets.

Table 1 Vote-buying practices in the Romanian elections (2008–2012)

Source: Adevarul, Cotidianul, Evenimentul zilei, Gandul, Jurnalul National, and Mediafax.

Treating appears to be the most popular vote-buying practice among the Romanian parties during electoral campaigns or during election days. It takes various forms, from concerts (where food is provided) and feasts thrown for the electorate, to bags with gluttony or clothes, free 1-day excursions, and services provided for free, such as medical consultations or car washing. There are two reasons behind its extensive use. First, parties can argue that these are not vote-buying actions but charity events or treating, which match the legal requirements. The legislation allowed, until 2012, the distribution of symbolic goods with the party logo on them (e.g. t-shirts, lighters, pens) (Gherghina, Reference Hopkin2013). The new law, adopted several weeks before the 2012 elections, allows parties to distribute goods with a maximum value of 2.5 €. Second, treating is likely to reach more voters at a lower cost than outright vote-buying. For example, the costs of a feast thrown for a few hundred voters are significantly lower than money given to each individual voter. Based on media reports, when bought separately, a vote costs on average 12 €.

The numbers in Table 1 indicate widespread vote-buying throughout the entire territory of the country – there are quite a few counties (out of a total of 41) listed in brackets. It is relevant to note that the three major parties (PSD, PDL, and PNL) established local organizations in every commune (several villages together), thus ensuring an exhaustive territorial coverage and extended possibilities of using such practices. When comparing the three major parties, the PNL uses the least vote-buying but its activity intensifies as soon as it gets into an electoral alliance with the PSD. The PNL appears to use more vote-buying when in government, for example, in 2008 and 2012, compared with the situations when it is in opposition. For the other two parties, the propensity of vote-buying is not connected with their government or opposition status. They use this clientelistic linkage in almost every instance. For example, before the 2009 presidential elections the PDL was incumbent and the PSD in the opposition and the intensity of their vote-buying activities does not differ significantly. Similarly, the vote-buying does not change when the party gets into opposition. For example, the PSD was in government before the 2004 legislative elections and in opposition before the 2008 general elections and 2009 presidential and EU elections. However, there is no decrease in terms of bribery.

The number of criminal case files registered at the High Court of Cassation and Justice substantiate the empirical evidence from media reports. For all elections and referendums in 2008 and 2009, the Court has analyzed a total number of 7956 police-documented cases of vote-buying. For the 2012 local elections there are 2052 cases, while in the 2012 referendum there were 632 cases (Agerpress, 2012).

The money used for vote-buying comes from private sources and can take two forms: super-fees and donations. A super-fee refers to supersized party membership fees paid by specific members. The average value of a regular fee/month is 2 € and all fees that exceed the value of 10 minimum wages should be declared (super-fees). Donations are money coming from private individuals and firms. Our analysis lumps them together because quite often CEO’s make individual donations in addition to their firm’s contribution. This procedure masks the real donation made by a private firm. Table 2 summarizes the amounts received by each party between 2008 and 2012; the figures are those reported by parties. It can be easily observed that the amount of both super-fees and donations is considerably high in election years (2008, 2009, and 2012) compared with non-election years. In light of our argument, these hikes in funding during electoral years can be linked to the costs during campaigns and elections. As the three major parties have had relatively good chances to end up in the government coalition (with the exception of 2012), the received amounts are substantial.

Table 2 Private donations received by the Romanian political parties (million €)

Note: In 2012, there is an additional 4.10 million € for the USL (PSD+PNL).

Source: Official Gazette (2009–2013).

The collected data have allowed us to check where the top donors are located. Their territorial dispersion brings evidence linking them to vote-buying. Each of the three major parties counts on extensive private contributions in those counties where many vote-buying activities take place (Table 1). The PDL has a large amount of donations in Bucharest (around 30% of top donations) and Cluj (10–20% of top donations). The PNL benefits from substantial contributions of private companies based in Bucharest (around 27% of top donations). The PSD has substantial donations from companies in Teleorman (40–51% of top donations) and Constanta (17–97% of top donations).

The horizontal linkage: parties and private contractors

Our argument is that some of the private money from Table 2 follows the horizontal linkage presented in Figure 2. This linkage means that political parties allocate public resources to private contractors through public procurement in exchange for formal or informal contributions. Let us take a close look at this exchange in Romania between 2008 and 2012.

The size and problems of public procurement make it efficient in transforming public funds into private funds. The European Commission estimates the average value of public procurements in the EU Member States at 18% of the country’s GDP, while Romania allocates ∼10% of its GDP (Eurostat, 26.03.2012). The procurement budget is not included in the annual national budget as a stand-alone category, but as part of each public authority’s budget, making it extremely difficult to investigate it rigorously.

There are two major categories of problems regarding public procurement procedures in Romania. First, there is the issue of proper control mechanisms. Although the Electronic System for Public Procurement (SEAP) is active since 2006, in 2011 only 16% of enterprises in Romania opted to access tender documents and specifications in the electronic procurement system, compared with the EU average of 21%. It is common practice for the open advertisements on SEAP to be discussed or negotiated in person between a representative of the contracting authority and the winning economic operator. While official standards have been set to establish the framework for each contracting authority throughout the year, there are large difference between these principles and what happens in practice. Most of these refer to the allocated budget for different procedures, and to the disregard for the initial inventory of necessities (Romanian Court of Accounts, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011; Ministry of Public Finance, 2010, 2011). Second, there are preferential criteria set in the tender book with the purpose of favoring certain contractors, in contradiction to legal provisions (Government Decree 34/2006). Another way to exert positive discrimination for certain economic operators is to change the selection criteria during the procedure, leaving ‘unwanted’ applicants with insufficient time to comply.

To illustrate how the horizontal linkage functions, we have matched the donations of private contractors with their benefits from private procurement. In this case, the benefits come from direct allocation of public contracts, or from open contest public procurement procedures. Table 3 includes 10 examples for each major party whose activity is mostly based on the direct allocation of public contracts, that is, the fastest and safest procedure of employing private contractors by public institutions. The final list of matches between public contracts and party financing is considerably longer. In addition, many donors have indirect benefits from public policy choices that do not necessarily involve the direct transactions, like in the case of public procurement contracts. A special interest in favorable regulation and policies is found in the case of companies from sectors such as energy distribution, agriculture, or cargo activities.

Table 3 Top donors with public procurement contracts (amounts in €)

Source: Official Gazette (2009–2013) and Public Procurement announcements.

The activity profiles of these companies indicate the extent to which their revenues are based on public procurement contracts. All three parties have many top donors with business activities in the fields of constructions, infrastructure, and energy distribution. It must be noted that the companies made efforts. Some top donors divide their contributions into several payments so that without a proper analysis of the data, the donations would appear modest or of marginal value.

At the same time, among the top donors that benefit from public procurement contracts, some of the private firms contribute to the campaign of more parties (e.g. SC Victor Construct in Table 3). When comparing party donations to the main competing political parties, there is a pattern of multiple donations for 65 out of 1430 donors in the period 2007–2013. While the percentage of such multiple donors is relatively small – 4.6%, we see that their total donation value is substantially higher – 14.03%.Footnote 6 Taking into consideration that many of these donations are proxies for larger exchange-based mechanisms, we can detach a tendency of cartelization for top donors. Still, as the figures show, this is not a mainstream element of the clientelistic relationships presented here, and the vast majority of donations remain politically focused on a single beneficiary.

This evidence suggests that most of the public procurement problems can be traced to the construction and infrastructure sectors, where the value of the awarded contracts is substantially bigger than in other sectors (Doroftei and Dimulescu, Reference Freidenberg and Levitsky2015). These are also sectors where most of the public works would necessitate agreeable relations with the political awarding authorities across several mandates, and would constitute a strong incentive for political engagement through funding, on behalf of the private contractors.

Our bi-dimensional model of clientelism, in which the horizontal level focuses only on resource accumulation, shows congruence with the contextual evidence mentioned in the previous paragraphs. Since firms bear little interest in vertical clientelism, that is, electoral mobilization, they supply more parties with resources to maximize their chances of getting public procurement. In addition, this procedure is consistent with the earlier discussed cartelization of political parties in Romania. There is high likelihood of inter-party cooperation at county levels – the place where most public procurement activity is deployed. As a final detail regarding the donors’ profile, the PNL receives donations from investment companies. Apart from their direct interest in public procurement, these companies may be a façade for other firms. Public companies might prefer to reroute their donations so that they are not directly linked to the party.

A close look at these donors’ economic activity over time reveals two relevant aspects for the clientelistic nexus. Many top donors record significant hikes in their activity during electoral years. For example, most donors of the PDL have a turnover increase by 10-fold in the electoral years of 2008–2009 (when the PDL was in government next to the PSD or alone). Also, in the case of the PNL, turnovers of top donors expand significantly during election years and some of the companies cease to exist after these years. The latter may suggest an instrumental use of private companies with the purpose of channeling public funds into party organizations.

Conclusions

This article developed a bi-dimensional model of clientelism that emphasized the existence of a horizontal linkage between political parties and private contributors. The core argument was that political parties with minimal organizations reduced the spectrum of clientelistic exchanges to vote-buying and engaged in cooperation with external actors to secure the necessary resources. Accordingly, public resources were no longer used in relationship with the electorate, but with private campaign donors. The latter benefited from public procurement procedures and continued to supply financial support to political parties.

This study presented evidence on the relationship between political parties and private contractors, and as such it developed a framework for analysis that moves beyond fragmented relations (i.e. rich donors – political parties, politicians – corrupt contractors, informal electoral exchanges based exclusively on public resources). While the literature has recognized both axes (i.e. political parties relationship with resource rich constituencies, and political parties clientelistic relationship with the electorate) it has never before attempted to correlate all three components, and to trace informal sources of funding with informal electoral exchanges, in an empirical, systematic analysis.

The analysis of Romanian parties between 2008 and 2012 illustrates the functioning of this clientelistic model. Empirical evidence showed how parties rely on a relatively small percentage of members and gradually abandon the idea of personal favors and pork-barrel as clientelistic exchanges. Instead, they focus extensively on vote-buying practices – in the form of outright vote-buying, treating, and conveyance – and they require financial resources. Such resources are provided by private firms that receive, in exchange, preferential access to public procurement. As Romanian politics is cartelized, these exchanges take place at large scale (i.e. the most important political parties) and on an iterative basis.

Since the investigated case study is only illustrative, the applicability of the model is likely to be broader. We expect it to be testable in settings with (partial) features of cartel politics and limited party organizations. The most important implication of this article is the inclusion, in the clientelistic model, of a clear linkage between political parties and private contributors. Along these lines, the theoretical contribution lies in the identification of a second clientelistic dimension that deserves further investigation. While we have identified some empirical mechanisms in the Romanian case, future research can focus on the diversity and challenges of horizontal clientelistic linkages in different settings. Our analysis focused on a case with political parties with weak organizations and it is useful to assess the character of clientelistic exchanges under relatively strong party organizations. Furthermore, research can explore the way in which these horizontal connections between parties and private companies shape the vertical linkage between political parties and voters.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Julia Fleischer, Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik, Maria Spirova, Saskia Ruth, and Frank de Zwart for their useful comments and constructive criticism on earlier drafts of this paper.