Introduction

In his seminal work The Gift Relationship, Titmuss (Reference Titmuss1970) asserted that paying people to do a prosocial act sometimes makes them less likely to do it. In essence, Titmuss argued that, in the context of blood donation, attempts at crowding in selfish (or extrinsic) motivation through monetary incentives simultaneously crowd out prosocial (intrinsic) motives. In other words, a good deed might be considered less good if one gets paid to do it. People may, therefore, be less inclined to act altruistically when getting paid to do so. Several studies have tested Titmuss’ hypothesis about motivational crowding out in the context of blood donation, and in large, found that Titmuss was correct (Ferrari et al., Reference Ferrari, Barone, Jason and Rose1985; Reich et al., Reference Reich, Roberts, Laabs, Chinn, McEvoy, Hirschler and Murphy2006; Goette & Stutzer, Reference Goette and Stutzer2008; Mellström & Johannesson, Reference Mellström and Johannesson2008; Goette et al., Reference Goette, Stutzer, Yavuzcan and Frey2009; Lacetera et al., Reference Lacetera, Macis and Slonim2012).Footnote 1 Studies have also found that monetary incentives sometimes lead to reduced efforts in a wide array of prosocial behaviors. For example, volunteers going door to door collecting money for charity collected less when offered a small monetary reward (Gneezy & Rustichini, Reference Gneezy and Rustichini2000). Likewise, several experiments have found that monetary payments sometimes reduce effort in various laboratory tasks (Deci et al., Reference Deci, Koestner and Ryan1999; Frey & Jegen, Reference Frey and Jegen2001; Fehr & Gächter, Reference Fehr and Gächter2002; Ellingsen & Johannesson, Reference Ellingsen and Johannesson2007). However, monetary incentives are not the only external factor that may crowd out intrinsic motivation. In this study, we extend the research on Titmuss’ hypothesis by exploring if external manipulations in the form of nudges crowd out prosocial behavior and warm glow.

Although nudges have been shown to effectively promote prosocial behavior in many situations, recent studies have shown that nudges sometimes backfire, leading people to resist what they perceive as illicit attempts to shape their behavior (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2017; Arad & Rubinstein, Reference Arad and Rubinstein2018; Reijula et al., Reference Reijula, Kuorikoski, Ehrig, Katsikopoulos and Sunder2018; Jachimowicz et al., Reference Jachimowicz, Duncan, Weber and Johnson2019; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Dimant and Schmidt2020). For example, Arad and Rubinstein (Reference Arad and Rubinstein2018) found that some people refused to adopt a savings program for which the government used nudging to promote, even though the arrangement itself was considered desirable. A possible reason for why nudges sometimes backfire is that people may react with a psychological reactance in situations where they feel that they are being manipulated into making certain choices (see Brehm & Brehm, Reference Brehm and Brehm1981). Although nudges, in theory, should preserve the freedom of choice, they can still amount to some level of pressure or result in a feeling that one should behave in a certain way. Because people derive additional utility from behavior that enhances their reputation (Frey & Jegen, Reference Frey and Jegen2001; Bénabou & Tirole, Reference Bénabou and Tirole2003; Ellingsen & Johannesson, Reference Ellingsen and Johannesson2008), nudges could plausibly also crowd out prosocial behavior simply because nudged prosocial behavior generates less utility than non-nudged prosocial behavior in terms of reputational benefits. An altruistic act may be viewed as less altruistic when being nudged, making it less attractive.

It has long been thought that observability and public recognition for prosocial behavior increases willingness to act prosocially. Experimental evidence for this has been found both in field and in laboratory settings, see Andersson et al. (Reference Andersson, Erlandsson, Västfjäll and Tinghög2020) for a review of the literature. However, in recent research, Savary and Goldsmith (Reference Savary and Goldsmith2020) cast doubt on this conclusion, instead finding evidence suggesting that public recognition undermines the intrinsic motivations for altruistic acts. Similarly, Wu and Jin (Reference Wu and Jin2020) found that nudges involving public recognition tarnished the perception of people behaving prosocially, by making observers think that prosocial behavior was a result of nudging, rather than spontaneous prosocial preferences. Little is, however, known about whether such counterproductive effects extend to actual behavior.

In addition to crowding out actual prosocial behavior, nudges may also crowd out warm glow. Warm glow can be described as the emotional satisfaction that stems from the act of giving or ‘doing good’, disregarding the actual impact of one's generosity and reputational benefits (Andreoni, Reference Andreoni1989, Reference Andreoni1990). Since warm glow helps people to maintain a self-image of being moral and fair-minded, an essential factor is how people perceive their own actions and the motivations behind them. Thus, if someone feels pressured or tricked into an action, the prosocial act might be less rewarding in terms of experienced warm glow. It could also induce other unintended negative reactions such as avoidance behavior (Andreoni et al., Reference Andreoni, Rao and Trachtman2017; Damgaard & Gravert, Reference Damgaard and Gravert2018). As an illustration, people sometimes avoid situations where they are being asked to give, although they are willing to give when being asked, suggesting an important difference between ‘giving’ and ‘giving in’ (see, e.g., Cain et al., Reference Cain, Dana and Newman2014), where the latter refers to prosocial behavior in which one reluctantly engages. Nudges may make an altruistic act more likely to be experienced as ‘giving in’ rather than spontaneous ‘giving’. The amount of warm glow felt following a donation is, thus, potentially higher for a person who is not being nudged into giving, at least when the nudge is transparent.

A common critique against the use of nudges is that they are often very subtle and not as transparent in how they are used to influence behavior as other more traditional policy interventions such as mandates (Dhingra et al., Reference Dhingra, Gorn, Kener and Dana2012; Hansen & Jespersen, Reference Hansen and Jespersen2013; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2016). Thus, while nudges are less coercive as a policy tool, they are more open to criticism about relying on manipulation for changing behavior. It has also been argued that this nontransparency is one of the reasons that nudges are effective in changing behavior (Bovens, Reference Bovens, Grüne-Yanoff and Hansson2009). However, studies on default nudges have not found any clear evidence supporting the hypothesis that transparency reduces the nudges’ positive effect on intended behavior (Loewenstein et al., Reference Loewenstein, Bryce, Hagmann and Rajpal2015; Kroese et al., Reference Kroese, Marchiori and de Ridder2016; Steffel et al., Reference Steffel, Williams and Pogacar2016; Bruns et al., Reference Bolton, Dimant and Schmidt2018). Less work has been done to investigate the effect of transparency of other type of nudges, with a notable exception of Kantorowicz-Reznichenko and Kantorowicz (Reference Kantorowicz-Reznichenko and Kantorowicz2019), who found that increased transparency of disclosing information about others’ behavior actually reduced the number of subjects making a desired choice in a lottery, defined as the choice that maximized the expected payoff. In the present study, we explicitly manipulate the transparency of nudges across conditions in a preregistered experiment. Since nudges differ on the extent to which they are transparent by themselves, we test three different types of nudges: (i) a default change nudge, where subjects need to actively opt out from a preset alternative, (ii) a social norm nudge, where subjects are informed about others’ behavior, and (iii) a moral nudge, where subjects need to think about what is morally right before making a decision. Following Titmuss’ hypothesis, the crowding-out effects of the nudges should be more pronounced for nudges that are more transparent (i.e., the social norm and the moral nudge) compared with the default nudge, which has a lower innate level of transparency. Arguably, the effect of our external manipulation of transparency should be weaker for nudges that have a higher innate level of transparency.

Methods

The study and main analyses were preregistered at the Open Science Framework (OSF) and the data are available at the project's OSF repository.Footnote 2 We report all conditions and measures included. Sample size was determined in advance, and analyses were conducted only after data collection was completed.

Subjects and setting

Subjects in an online experiment were recruited from Prolific (Palan & Schitter, Reference Palan and Schitter2018). All subjects gave their informed consent to participate in the study. A total of 1098 subjects completed the survey, with a mean age of 32.2 years (SD = 0.34) and 48.9% women. In total, 38.4% were from the UK, 18.3% from the USA, roughly 10% each from Portugal and Poland, and 24.7% from other countries. There were no statistically significant differences in background characteristics between conditions, indicating that our randomization was successful. Subjects were rewarded 50 cents as a showup fee in addition to the bonus payment contingent on their own decision. Two subjects failed the included attention check and were, thus, excluded from the analysis. The experiment was conducted in English and programmed in Qualtrics.

Experimental design

For subjects in all conditions, the experiment consisted of three parts. In the first part, subjects were informed about UNICEF, answered questions about UNICEF, and were shown an advertisement from the organization. This was done to make subjects feel that they were doing something worthwhile, before making their decision to donate money or not in the second part. In the second part, participants were endowed an extra 50 cents, which they could choose to donate to UNICEF or keep for themselves. In the third part, subjects answered a series of questions about how happy they were with their choice and to what extent they experienced the nudge as manipulative.

At the outset of the experiment, subjects were randomly assigned to one of seven conditions, either a control condition without any nudges or one of six conditions involving nudges. Table 1 gives an overview of all conditions. Two conditions included a default change nudge, two conditions included a social norm nudge, and the final two included a moral nudge. The default nudge added a default choice, so that yes and full donation (50 cents) were the preselected alternatives. The other conditions had no preselected alternatives.Footnote 3 In the social nudge conditions, subjects were presented with the information: ‘Previous studies have shown that about 80% of subjects choose to donate money in similar situations.Footnote 4 In the moral nudge conditions, subjects were asked to respond to the following question before making their decision to donate or not: ‘What do you think is the most morally right to do, in this situation?Footnote 5

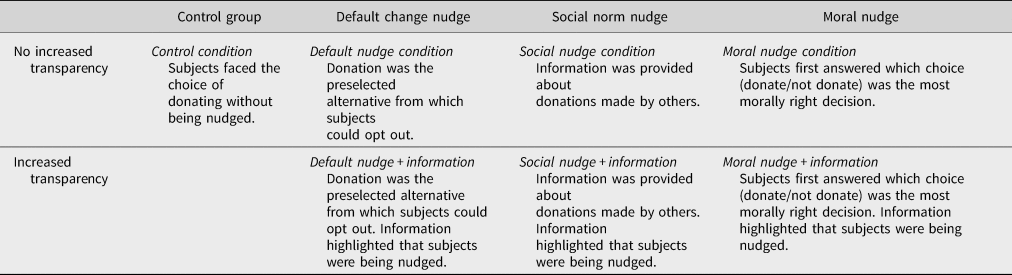

Table 1. Description of experimental conditions.

The default and social nudges were chosen partly because they represent nudges commonly used in public policy (Thaler & Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008). All nudges were also partly chosen because they differ in their innate level of transparency, that is, whether it is clear that they are an attempt to influence behavior even without explicitly saying so. The default nudge is arguably the least transparent nudge out of the three, while especially the moral nudge is quite transparent in itself as an attempt to influence behavior. The innate transparency level of the social nudge, where subjects are informed about the behavior of others, is arguably somewhere in between these two. To further explore the effect of transparency of the nudges, we included three conditions that were identical to the three nudge conditions but also included an explicit message to increase the transparency of the respective nudge. This information highlighted the fact that the subjects were being nudged and disclosed motivation behind such nudges and their potential to affect decision-making. For example, the nudge information for the default change nudge read: ‘Before proceeding, please note that when asked to donate, the default choice (pre-selected) is set to donate. Changing which choice is the default choice is a method that can be used to affect behavior. This method is frequently used by companies and organizations to promote certain behavior. It has been proven to have a large impact on choices and behavior for example when giving consent for organ donations, choosing insurance policies, eating healthy and in many other situations.’ The messages in the other conditions were similar but adjusted for the respective nudge. For complete experimental instructions, see Supplementary Material.

Materials

To measure prosocial behavior, subjects were faced with a dictator game where they could donate any amount between 0 and 50 cents to a charitable cause (UNICEF). The structure of the game was that subjects first answered a yes/no question if they wanted to donate, and if yes was selected, they indicated using a slider how much of the 50 cents to donate to UNICEF. This design was chosen, since it has been found that potential donors make their choices in two steps, where the first step is whether to help or not, and the second is how much to help (Dickert et al., Reference Dickert, Sagara and Slovic2011).

To measure warm glow after making their donation choice, subjects were asked if they agreed with the statement ‘I am happy with my choice to [donate/not donate].’ Subjects answered on a four-graded Likert scale with the options ‘Strongly Agree’, ‘Agree’, ‘Disagree’, or ‘Strongly Disagree’.

To measure perceived manipulation, whether the subjects thought that they were being manipulated by nudges when deciding to donate or not, subjects in the six conditions who faced nudges were asked: ‘When you made your choice to donate or not, did you feel like the [pre-selected choice/information about how much other people donate/question about what was morally right] was an attempt to manipulate your answer? (Yes/No).’

Results

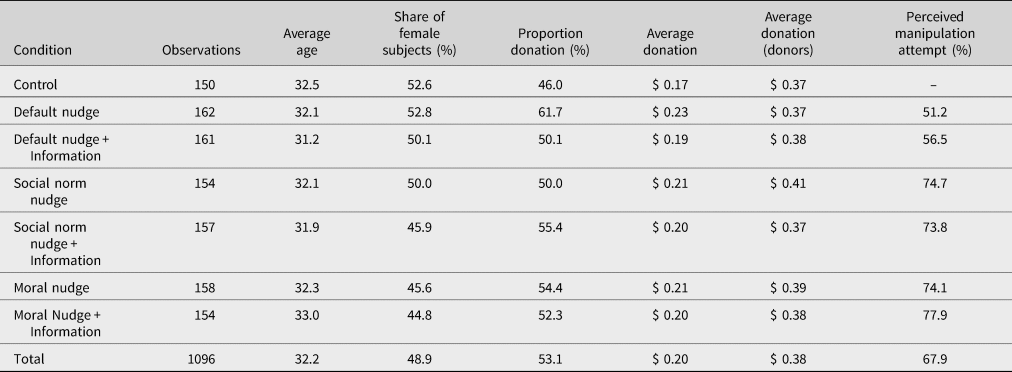

Summary statistics are presented in Table 2. Across all conditions, 53.1% of subjects donated money to UNICEF. The average amount donated across all conditions was 20 cents (i.e., 40.0% of the full amount). Across conditions, the donated amount ranged between 17 and 23 cents. When excluding nondonors, the average donation ranged between 37 and 39 cents. Among those who donated, the majority (61.5%) donated the full amount. A small spike (11.3%) was also found at the 50/50 choice of giving 25 cents.Footnote 6, Footnote 7

Table 2. Summary statistics.

The perceived manipulation of nudges was high, ranging from 51.2% in the default condition to 77.9% in the moral nudge condition with information. Whether or not nudges were perceived as attempts to manipulate behavior was uncorrelated with whether or not subjects received information making the nudge transparent (r = 0.05 for the default nudge and moral nudge and r = −0.01 for the social norm nudge).

Do nudges crowd out prosocial behavior?

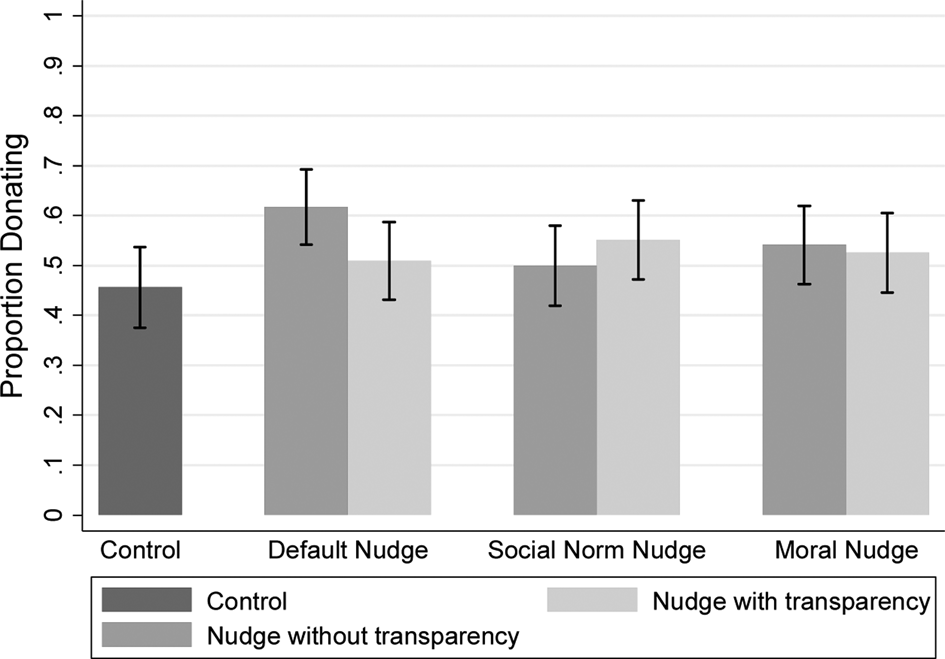

Figure 1 shows the proportion of subjects donating in each condition. Donations increased in all six nudge conditions compared with the (no-nudge) control condition, where 46.0% of the subjects donated. Thus, we find no crowding-out effect for any of the nudges. Donations were the highest in the condition with the default nudge (61.7%) and the social norm nudge with information (55.4%). The difference in donation compared with the control condition for these conditions was statistically significant (p < 0.05), while the other conditions were not statistically different compared with the control condition.

Figure 1. Proportion of subjects donating to charity in each condition, with 95% confidence intervals.

The effect of increased transparency on donations varied across the three different nudges, but with no overall significant effect when pooling the data t(942) = 0.78, p = 0.437. For the default nudge, the nudge with the lowest inherent level of transparency, the information explicating the use and purpose of the nudge decreased the share of donors by 11.6% points compared with the default nudge condition without this additional information, t(321) = 1.96, p = 0.025. For the social norm nudge and the moral nudge, the increased transparency had no significant effect. The proportion of donors increased by 5.4% points for the social norm nudge, t(309) = 0.95, p = 0.17, and decreased by 2.1% points for the moral nudge when the information was included, t(310) = 0.32, p = 0.37.

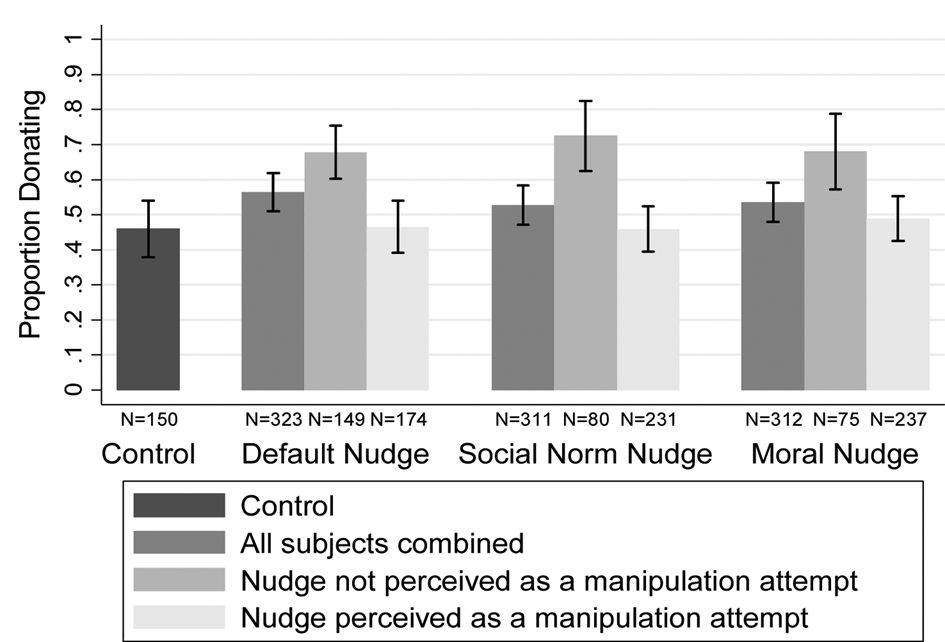

While we, in Figure 1, compare donations between the exogenously manipulated conditions, we also tested differences in donations depending on whether or not the nudges were perceived as manipulative. As shown in Table 2, the share of subjects who perceived the nudges as attempts to manipulate behavior differed between nudges, with the default nudge being perceived as the least manipulative. Figure 2 shows the share of subjects who choose to donate, separated by whether the nudge was perceived as manipulative or not. For subjects who did not perceive the nudge as an attempt to manipulate behavior (N = 304), the nudge was effective in increasing prosocial behavior. For subjects who viewed the nudge as an attempt to manipulate behavior (N = 642), the proportion donating was similar to the (no-nudge) control condition. Thus, even though people felt that they were manipulated by the nudge, it did not crowd out prosocial behavior. The positive effects of the nudges on prosocial behavior were, however, driven by increased donations made by subjects who did not perceive the nudge as an attempt to manipulate behavior.

Figure 2. Proportion of subjects donating to charity and perceived manipulation attempt of nudges. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

Do nudges crowd out warm glow?

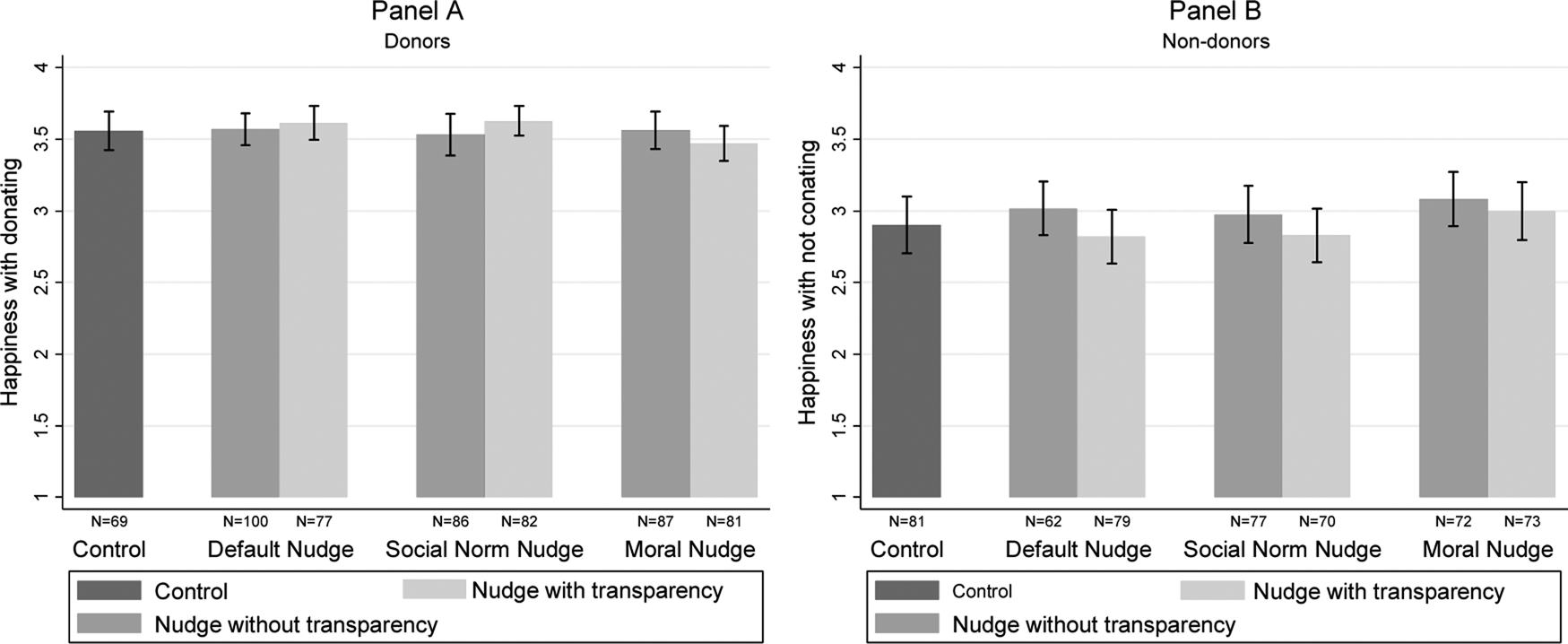

Figure 3 shows subjects’ experienced warm glow, measured as happiness with their choices, for donating subjects (Panel A) and nondonating subjects (Panel B). For both donating and nondonating subjects, there were no statistically significant differences in happiness with choice between subjects who were nudged and subjects in the no-nudge control condition (donors t(580) = −0.074, p = 0.941; nondonors t(509) = 0.496, p = 0.620). Thus, we find no indication that nudges crowded out warm glow. Those who donated were happier with their choice (M = 3.57, SD = 0.56) than those who did not donate (M = 2.94, SD = 0.83), t(1091) = 14.67, p < 0.001.

Figure 3. Happiness with choices for (A) donors and (B) nondonors. Numbers on the scale represent how much subjects agreed with the statement ‘I am happy with my choice to [donate/not donate]’: 1 – Strongly Disagree, 2 – Disagree, 3 – Agree, 4 – Strongly Agree. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

Making the nudges more transparent had no statistically significant effect on how happy donating subjects felt with their choice. This null finding was consistent when making comparisons for each nudge individually and when pooling all conditions. For nondonating subjects, there were no differences between conditions with and without information to increase transparency, comparing each nudge individually. However, pooling all nudges together shows that subjects in the nudge conditions with transparent nudges were less happy with their choice (M = 2.88, SD = 0.82) than those who were nudged without explicit information about the nudges (M = 3.02, SD = 0.81), t(428) = 1.80, p = 0.037. The effect is, thus, small and should be interpreted with caution until replicated.

Discussion

The arguably highest form of giving in most cultures is anonymous giving to unknown strangers without any external pressure or motivation to do so. Following the idea that extrinsic motivations can crowd out intrinsic motivation, we tested if nudges crowd out prosocial behavior and decrease warm glow from donations. Our results show no indication that nudges crowd out prosocial behavior. Instead, donations increased in all six conditions where people were nudged compared with the (no-nudge) control condition. Previous studies have found that nudges cause psychological reactance against the desired behavior for a significant group of people and that concerns of manipulation are the driving force of this reactance (Arad & Rubinstein, Reference Arad and Rubinstein2018). In relation to this, our study shows that, while a group of people see the nudges as manipulative, they do not react by engaging in prosocial activities to a lesser degree than in the absence of the nudge. The nudge simply has no effect on this group of people, and the positive effects of the nudges are driven by the people who do not perceive the nudges as manipulative. Put in other words, we see no indication that people who would like to engage in prosocial behavior avoid doing so when they are being nudged toward that particular behavior.

Furthermore, we measured warm glow and tested if this positive feeling was crowded out by nudges. If nudges reduce warm glow, this could have a direct effect on altruistic people's well-being, by reducing their own utility derived from the act of giving. We measured warm glow by asking subjects how happy they were with either donating or not donating. For both donors and nondonors, we found no differences in happiness with choice depending on whether subjects were nudged or not. Wu and Jin (Reference Wu and Jin2020) found that the use of nudges tarnished the perception of people behaving prosocially, by making observers think that prosocial behavior was less genuine. Our findings, thus, indicate that this effect does not extend to the assessment of own behavior influenced by nudges. An interpretation of this is that nudges make other people's prosocial behavior less praiseworthy, while one's own prosocial behavior is unaffected by nudges. Although we found no overall crowding out of warm glow, it is important to note that donors who perceived the nudge as manipulative were less happy with their choices. Thus, for nudges to be unambiguously welfare-improving, it is important to limit the extent to which people feel manipulated.

We also tested if crowding out of prosocial behavior and warm glow depends on the transparency of the nudges. We found that making the default nudge transparent decreased its positive effect on altruistic behavior. However, we found no crowding out of prosocial since subjects still donated more than in the control group. Previous studies on the effect of transparency have suggested that increased transparency does little to affect the effectiveness of default nudges (Loewenstein et al., Reference Loewenstein, Bryce, Hagmann and Rajpal2015; Bruns et al., Reference Bruns, Kantorowicz-Reznichenko, Klement, Luistro Jonsson and Rahali2018). Our results tell a different story, since increased transparency of the default nudge resulted in less giving. A possible reason for why we find a negative effect on giving for the default nudge and not the other nudges tested is that the default nudge is inherently less transparent in comparison with the other nudges. Thus, it is not surprising that disclosing information about the purpose of the nudge has an impact for the default nudge, while this effect was negligible for the inherently more transparent nudges.

Some limitations of our study should be noted. First, the stake size is admittedly small. It is, of course, possible that our results could be affected had we had higher stakes. Although a recent meta-analysis indicated that an increased stake size tends to generate slightly more giving (Larney et al., Reference Larney, Rotella and Barclay2019), it gives us no reason to believe that the general findings from this study would change if subjects had made decisions involving higher stakes. Second, in this study, we explore potential crowding-out effects limited to ‘prosocial’ nudges, which are a specific type of nudge where choice architecture is used to facilitate decisions that involve own sacrifice to benefit others (Hagman et al., Reference Hagman, Andersson, Västfjäll and Tinghög2015). Thus, we do not know whether our results will extend to traditional ‘pro-self’ nudges that primarily aim to increase individuals’ own well-being. This is a venue for future research. Finally, it should be noted that, in this study, participants made their decision to donate or not in a private context. It is possible that we would see a crowding-out effect if decisions were made in a more public context where people could be observed when making their decision.

To conclude, our findings are important for understanding the consequences of nudging in a broad sense, since no previous study has explored to what extent nudges crowd out prosocial behavior and warm glow. As there are many examples of extrinsic incentives crowding out prosocial behavior, as hypothesized by Titmuss, similar effects could potentially be expected for nudges as well. However, we find no indication that nudges crowd out prosocial behavior. Generally, our results are good news for people working with behavioral insights in public policy, since they suggest that concerns about unintended motivational crowding effects on behavior have been overstated. At least when it comes to prosocial behavior.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2021.10.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (grant number: MMW 2014.0187) and the Swedish Research Council (grant number: 2018.01755). Funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no competing interests that could have appeared to influence the submitted work.