What role do international organizations play in facilitating “peaceful change” in world politics? Intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), more commonly known today as formal international organizations (IOs), have been important players in global politics for more than two centuries. Their number, size, and functions have grown since the end of World War II and, more importantly, since the end of the Cold War in 1991. Today, close to 8,000 IOs saddle the world, and their number has significantly increased since 1979. In addition, we have witnessed an exponential increase of informal IOs, such as the G20, in many functional arenas in world politics. Both formal and informal IOs have been encompassing many dimensions of interstate activities and playing meaningful roles in international politics, especially in solving collective action problems, be it security, economic, environmental, or global health challenges. Interstate cooperation and coordination in today’s world are unfathomable without taking into consideration the role played by these diverse IOs.

There is a general belief, especially among liberal and constructivist schools of international relations, that these organizations have fundamentally transformed international politics and state identities as they form critical pillars of global governance and the liberal international order (LIO). In the Kantian tripod scheme, international institutions play a pivotal role, along with economic interdependence and democratic institutions, in bringing about peaceful change.Footnote 1 In fact, all types of states, including nonliberal ones, have found them useful for the purpose of negotiation, socialization, and power politics, and as such institutional means and interactions have many a times supplanted coercive bargaining, especially through war. Soft balancing is one such mechanism that secondary states have resorted to through institutional balancing and institutional bargaining.Footnote 2 Whereas realists tend to emphasize the instrumental role of IOs, rationalists and liberal institutionalists have focused on how they serve as forums for bargaining and consultations, while constructivists have explored the actorness of IOs and their potential for discursive agenda setting.Footnote 3 Recently, a number of studies, agnostic of interparadigmatic debates, have explored how institutional change, innovation, and impact take place in a complex political, legal, and administrative space affected by different types of actors, networks, and issue areas and varying levels of formalization and legalization.Footnote 4 While this literature adds important insights and nuances to our understanding of IOs, it also risks losing sight of the fundamental debates and big questions of international relations such as war and peace. In sum, we are yet to obtain a full sense of the actual impact of these institutions on change and how peaceful they are. A critical evaluation is necessary given the plethora of functions IOs are called upon to perform in the contemporary world.

Skeptics from the realist and critical schools contend that IOs reflect the power politics of the day and the interests of hegemonic powers. In other words, IOs are simply instruments for powerful states and their elites to pursue their interests, and they do not have an independent role in shaping interactions among states. Often these powers ignore IOs whenever a collision takes place between their interests and the organization’s mandate, thereby producing suboptimal outcomes. The UN Security Council has become the most prominent arena of such power politics, making it unable to perform its originally intended role of maintaining collective security. Critical theorists find these organizations, especially the economic ones, as helping the Western-capitalist order and maintaining the unequal and unjust world order. They do not find change, let alone peaceful change, as a product of the functioning of IOs.

How We Study Peaceful Change and International Organizations

This volume provides both a diagnosis of the ability of IOs to contribute to order transitions and suggestions of “cures” for their current shortcomings in promoting peaceful change. We explore the role of IOs in influencing peaceful change in world politics in different domains. In an era of systemic power transitions and increasing great power rivalry, as we are witnessing today, understanding the conditions for peaceful change is particularly important. The volume shows that while IOs may contribute to peaceful change in important ways, they do so as political actors (even when they shy away from viewing themselves in this way). As political actors, they contribute to the struggle over who gets what, when, and how in international politics, with important consequences for the prospects for peaceful change. This political process is not exclusively a great power game. In contrast, the analyses in the volume show how peace is cocreated (and obstructed) among a variety of actors and how agency is diffused in contemporary world politics.

The overarching research question of the volume is: What role do IOs play in influencing peaceful change in world politics? This question serves as the primary tool for organizing the volume and directs the theoretical discussion and empirical analyses of all chapters. Part I (this chapter) unpacks what we mean by peaceful change and IOs and explains how we organize our analysis and argument. In order to give a comprehensive answer to the overarching question, we break it down to two sub-questions, each of them guiding a section in the book. First, in Part II of the book, we ask contributors how to conceptualize “peaceful change” and how IOs fit into this process within the context of world politics, when analyzing from their theoretical perspective. Second, in Part III of the volume, we ask authors to draw upon empirical evidence, both historical and contemporary, to illustrate how particular IOs contribute to peaceful change. The concluding Part IV returns to the overarching research question and uses the theoretical discussions and empirical analyses of the book as a starting point for a critical reflection on how to understand IOs and peaceful change and the implications for world politics.

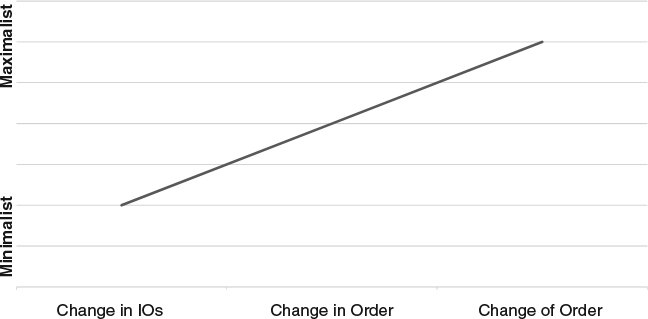

Peaceful change, in this volume, is defined as a continuum from a minimalist understanding depicting “change in international relations and foreign policies of states, including territorial or sovereignty agreements that take place without violence or coercive use of force” to an intermediate level perspective of “the resolution of social problems mutually by institutionalized procedures without resort to largescale physical force,”Footnote 5 and finally, to a maximalist understanding depicting “transformational change that takes place non-violently at the global, regional, interstate, and societal levels due to various material, normative and institutional factors, leading to deep peace among states, higher levels of prosperity and justice for all irrespective of nationality, race or gender.”Footnote 6 In the current international order, the main battlegrounds on the timing, content, and form of peaceful change are located at the intermediate level of this continuum. This is also where we would expect IOs to play the most important role – negatively or positively – for peaceful change as they entail more than merely a change in states’ foreign policies, but less than an acceptance of a cosmopolitan international society. Moreover, “peaceful change” is not equal to “peace” although we recognize that a perpetual or deep peace might be closely linked to the maximalist understanding of our definition of “peaceful change.” Sometimes peaceful change can produce violent or unsavory outcomes.

This definition has now become a starting point for a significant number of contributions in the emerging research program on peaceful change in world politics.Footnote 7 Therefore, it allows us to build on and contribute to this research program. It provides a shared starting point and signposts for different “depths” of peaceful change, while leaving it to the contributors to this volume to provide the theoretical arguments and empirical substance for minimalist, intermediate, and maximalist expressions of peaceful change. The final part of the book returns to the definition and discusses it further in the context of the arguments and findings of the volume.

By examining the potential of prominent theoretical perspectives on international relations to unpack the link between IOs and peaceful change and critically scrutinizing how selected global IOs contribute to peaceful change, we aim for this volume to be an invaluable source for students, scholars, and policymakers interested in peaceful change and IOs as well as current changes in the international order more generally. While acknowledging the potential importance of regional organizations for peaceful change, we focus on some key global IOs in this volume.Footnote 8 By analyzing the role of IOs in peaceful change from peacekeeping to trade, health, and the environment, and including both formal institutions such as the UN General Assembly and an informal organization such as the G20, we are able to identify the role of IOs in peaceful change across policy areas and to unpack the effects of formal institutionalization. While the role of the UN Security Council as a hub for discussion on peaceful change has waned since the end of the Cold War, the importance of many of the other IOs has increased. Global IOs may have (positive or negative) effects on peaceful change at the domestic, regional, and global levels. They are both products and producers of international order. Exploring how, when, and why they matter for peaceful change provides important clues for the development and outcome of the ongoing crisis in the LIO.Footnote 9

The Increasing Role of International Organizations in World Politics

We begin from an understanding of IOs as “associational clusters among states with some bureaucratic structures that create and manage self-imposed and other-imposed constraints on state policies and behaviors.”Footnote 10 Understood this way, IOs are the most important sites for the negotiation and renegotiation of international regimes, that is, “sets of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area of international relations.”Footnote 11 While IOs and regimes are not exactly the same, as the latter contain institutions, treaties, norms, and standards of behavior in specific areas, IOs provide the nuts and bolts of such regimes. For instance, the nuclear nonproliferation regime encompasses the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as the key organization, and the norms about nuclear acquisition, proliferation, and civil use of nuclear materials.

We acknowledge our definition is minimal and rationalist in orientation. Reflectivist scholars of both constructivist and critical perspectives may view IOs as not just “constraint” producing agencies, but ones that can create and shape interest and identities and produce maximalist changes. However, our definition will serve as an analytical anchor and starting point for individual chapters. We acknowledge that the theoretical discussions and empirical analyses of the volume may lead chapter authors to refine and even question this fairly traditionalist baseline understanding. However, in contrast to an “all-inclusive” definition, this minimalist understanding will allow authors to tease out what is particular about their theoretical perspective or their empirical case. For instance, the dividing line between formal and informal IOs is increasingly blurred and informal IOs play a still more prominent role in international relations.Footnote 12 While this may be seen as challenging our baseline understanding of IOs, the question is not whether it is “falsified” by informality but how and why the prospects for peaceful change are modified or even transformed by the increasing importance of informal IOs. They might not have a permanent bureaucratic structure or leadership. Likewise, the size, role, and significance of these informal IOs can vary depending on issue areas, and they may be global or regional, issue specific or wide ranging. The question as to whether they help preserve the status quo or support and facilitate change is an important one but is a matter of debate.

According to some analysts, IOs can be important, if imperfect, means of change in international order.Footnote 13 At times, they can also prevent peaceful change by favoring the status quo in power politics and supporting the existing orders of great powers or even provoke violent reactions if perceived as instruments of power by rivalling states.Footnote 14 The German, Italian, and Japanese responses to the League of Nations during the 1930s are examples of the latter. A critical examination of IOs as agents of peaceful change or the opposite is urgently needed as the existing literature does not deal with this dimension adequately. As noted earlier, this volume undertakes a critical examination on two dimensions. First, we explore how prominent theoretical perspectives on international relations view the connection between IOs (formal and informal) and peaceful change. What do “international organization” and “peaceful change” entail, when viewed through these theoretical lenses and how do IOs facilitate or obstruct peaceful change? Second, we explore a number of case studies focusing on some key global IOs that make up central parts of the institutional infrastructure of the current international order in order to understand how variation in formality, issue area, and membership affects the impact of IOs on peaceful change. Taken together, these two sections provide a highly important mapping of how IOs affect the prospect for peaceful change, which allows us better to understand the future of the rules-based international order currently challenged by a combination of increasing great power rivalry and populist nationalism.

The intellectual roots of peaceful change through international organizations date back to Immanuel Kant’s idea of a “perpetual peace” upheld by a federation of republican (democratic) states.Footnote 15 From the nineteenth-century European Concert onward, military conflict has often provided state leaders with the rationale and incentive to establish organizations and avoid a repetition of the horrors of the most recent war.Footnote 16 After World War I, Kant’s vision was reiterated by US President Woodrow Wilson, who while addressing the US Congress in January 1918 outlined a set of principles for the postwar order, including “a general association of nations” aimed at securing the independence and territorial integrity of states no matter their individual capabilities.Footnote 17 Since the end of World War II, economic globalization and the presence of nuclear weapons have increased economic and security interdependence, thereby underpinning the growing importance of effective institutional infrastructures for keeping and making peace.Footnote 18 At the same time, the reluctance of great powers to commit to institutional bargains – or even to implement whatever bargains they previously agreed to – undermines the effectiveness of institutions.Footnote 19 Even many small states, while generally supportive of international organizations, often free ride on the provision of collective goods – such as peace – by the great powers.Footnote 20

For most of the twentieth century and in the first decade of the twenty-first century, international organizations continued to play an important role in peaceful change. The result was a post-Westphalian, post–Cold War international system with increasingly intrusive international organizations, especially regimes in the economic and security areas.Footnote 21 Since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, traditional Western proponents of liberal internationalism have joined post-Communist states and developing countries in challenging the role and influence of international organizations on peaceful change.Footnote 22 Populists in liberal democracies as well as in authoritarian and semi-authoritarian regimes interconnect in their challenge of the liberal and normative institutional order.Footnote 23

The international institutional order has proved remarkably resilient in the face of these challenges.Footnote 24 Many of the day-to-day workings of organizations such as the UN, World Trade Organization (WTO), and NATO continue as before. However, this institutional activity has become increasingly marginalized in the workings of great power politics and consequently ineffective in influencing the big questions on peace and war. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the war in Syria are only two of the more notable recent examples of this trend.

Today, the so-called liberal international order is experiencing three unprecedented challenges related to the future development of IOs in world politics. First, the international power hierarchy is changing. The United States came out of the Cold War as the strongest power in the history of the modern state systemFootnote 25 but has since suffered a long-term relative decline, in particular vis-à-vis the rising China.Footnote 26 Europe has also seen a relative decline compared with Asia in general. China has increasingly been playing a key role in many international organizations by offering both financial and political support as well as engaging in intrusive policies. Other rising powers such as India and Brazil have also actively competed for power and influence through engaging in existing IOs and creating parallel institutions. The nexus between the IOs and the existing liberal order seems to be weakening. International organizations have become a new arena to reflect power politics among great powers during the period of potential order transition.

Second, these changes in the international distribution of power have been accompanied by increasing contestation of norms and institutions underpinning the so-called liberal international order.Footnote 27 Rising powers challenge and push for reform of existing organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or create new ones, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). As Zürn suggests, there are two forms of institutional changes, or counter-institutionalization in global governance. On the one hand, dissatisfied states can engage in regime shifting or forum shopping in order to reduce the relevance of existing but disappointing international organizations and relocate priorities to organizational venues, which better serve their interests.Footnote 28 A vivid example of this regime shifting can be drawn from many states’ shifting priorities from the WTO multilateral trade negotiations to regional “preferential trade arrangements,” such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. On the other hand, dissatisfied states can engage in competitive regime creation, which is to establish a new institution alongside an existing one in the same issue areas, challenging the governance authority of the existing institution.Footnote 29 The establishment of the AIIB and the New Development Bank is widely seen as a challenge of rising powers to the governance authority of the World Bank and the IMF in global financial governance.Footnote 30 Thus, IOs are important instruments and arenas for emerging powers to challenge international order and push for change through peaceful means. In addition, in the West and in the Global South, the impact of individual IOs as well as the institutional order more generally have an uneven impact on domestic constituencies, prompting them to support or challenge further institutionalization.

Whether or not these challenges will strengthen or weaken the LIO in the long run is a matter of debate as is to which extent they present a clearly articulated normative alternative to that order. However, the trend may in itself weaken the future effectiveness and resilience of the institutions as recent evidence suggests that large and global IGOs with heterogeneous membership stand a better chance of survival.Footnote 31 In the Euro-Atlantic core of the West, even long-time defenders of the international institutionalized order such as Britain and the United States have become increasingly unilateralist. This was particularly characteristic of the Trump Presidency, but President Biden’s intention to build an “alliance of democracies” may weaken the ability of existing institutions, the UN, in particular, to function as arenas for discussions between different types of governments.

Finally, changes in power and normative orders are altering the status and pecking ordersFootnote 32 with consequences for both “logics of consequence” and “logics of appropriate action.”Footnote 33 For example, Kyle Lascurettes suggests a “theory of exclusion,” arguing that dominant powers can use international organizations to “reorder the international system out of a desire to inflict harm upon a threatening force or entity.” In particular, states can use membership rules of international organizations that they share in common with other actors in the larger cause of “weakening, opposing, ostracizing, and above all excluding those entities they perceive as most threatening.”Footnote 34 In addition, states are using international organizations to make rules to legitimate the inclusion of some actors and the exclusion of others, creating a stratified system of political equals and unequals in the international system.Footnote 35

As noted in a recent stock-taking and discussion of the crisis in the rule-based LIO, we may soon face a systemic transformation of the same magnitude as the end of the Cold War, but with much graver consequences for the critical institutional infrastructure.Footnote 36 In the worst-case scenario, a systemic great power war will replace peaceful change.Footnote 37 Even if this is not the case, the lack of great power leadership may seriously weaken or collapse the institutional infrastructure for peaceful change,Footnote 38 or give way to a new system composed of a “thin” global order in combination with two competing orders dominated by China and the United States.Footnote 39

Understanding International Organizations and Peaceful Change

International organizations are important instruments for peaceful change. Sometimes they are actors of change, shaping and steering global governance by direct regulation or by orchestrating voluntary support and compliance.Footnote 40 At other times they are arenas for struggles over what to change and how, or instruments for great powers seeking to uphold the status quo or push for peaceful change for ideological or material reasons.Footnote 41 This complexity reflects that international organizations are “created by the commitments made by sovereign states,” at the same time as “their purpose is to bind those states to their commitments.”Footnote 42

Our volume focuses on three types of “change” related to international organizations. The first is the “change” or “evolution” of international organizations themselves. Authors examine under what conditions and how international organizations undergo peaceful change.Footnote 43 The second “change” refers to the interactions among international organizations, that is, the constitution of the institutional order, in the international system. For example, how can international organizations lead a peaceful change in the international order or parts of it, for example, global financial or environmental governance?Footnote 44 The last type of “change” is about power transition among great powers in the international system. How and to what extent can international organizations facilitate peaceful power transition between dominant states and rising powers in the international system? This is the most fundamental type of change: changes of the international order, for example, from an American to a Chinese-led international order. The interactions of these three types of change manifest the larger dynamics of order transition in the international system.

IOs have contributed to peaceful change in the Post-World War II era in a number of ways. Critical among them are the decolonization of over 150 former European colonies and the creation of the anti-colonial norm itself. A second area has been the non-nuclear norm as presented through the nuclear non-proliferation regime, its key pillars the NPT and the IAEA. The “tradition of non-use” or the “nuclear taboo” as some call it, has been partially supported by the efforts of the relevant IOs and the larger regime itself.Footnote 45 In the economic arena, negotiation through governance and monitoring by IOs have facilitated peaceful change and development, especially the WTO and its precursor the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) by avoiding many possible conflicts. In the health arena, the World Health Organization (WHO) has generated peaceful ideas for health care and disease prevention globally, although receiving some major criticisms toward its over-politicization. In international labor standards, international aviation, maritime laws, climate change, development assistance, and taxation many changes have now become a normal part of inter-state relations thanks to the working of IOs. Even if these issues did not produce violence, dispute prevention, and smooth functioning would not have been possible without institutional norms and rules created by IOs.

The United Nations General Assembly has offered a crucial venue to developing countries and second-ranking powers to bargain and influence policies through peaceful means. In fact, the General Assembly has performed better than the Security Council as a “parliament of the world” or as Paul Kennedy calls it: “Parliament of Man.”Footnote 46 The UN has been used as a soft balancing arena by second-ranking states to deny legitimacy to aggressive actions by powerful states, especially the US. The denial of a resolution by the UN Security Council supporting the US war on Iraq in 2003 was a good example.Footnote 47 Despite this, the Security Council has become moribund due to great power politics and the use of veto power, although on occasions it has stood up for peace and security.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has made many rulings that have contributed to peaceful adjudications of disputes among states. The Responsibility to Protect (R2P) is another major innovation that the UN introduced in 2005.Footnote 48 This has been criticized for selective use against vulnerable African states, but still it may have deterred acts of violence by regimes against defenseless populations in some contexts.

Regional organizations like the European Union (EU) and its many subsidiary arms have made major contributions to peaceful change in Europe and beyond. The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which lay the institutional groundwork that later developed into the EU, was founded by the Schuman Declaration aiming explicitly to make war “not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible” by pooling the steel and coal production of former enemies Germany and France.Footnote 49 From these beginnings, the two European great powers successfully developed an institutionalized “cooperative hegemony” in which the continued success and development of EU institutions became a joint goal serving as the starting point of a “normative power Europe” seeking to project peaceful change beyond the members of the institution.Footnote 50 Similarly, the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is credited with generating ‘negative peace’ in Southeast Asia.Footnote 51 In particular, ASEAN advocates a unique “ASEAN way” to promote quiet diplomacy, incrementalism, and consultation among states in the Asia Pacific region.Footnote 52 Although ASEAN is criticized as “making process, not progress” in regional affairs,Footnote 53 the “process-driven” confidence-building measures among major powers have contributed to the peace and stability in the Asia Pacific region since the end of the Cold War.Footnote 54

Therefore, from the realist power-related change and liberal interest-induced cooperation to constructivist identity-rooted transformation, IOs have played a critical role in creating various forms of peaceful change in both the minimalist and the maximalist senses in world politics. Our definition of minimalist vs. maximalist peaceful changes offers a vertical dimension or degree of peaceful change. The three types of peaceful change related to IOs in this volume – the institutional change inside IOs, the interactional change among IOs, and the transitional change between IOs and power dynamics in the international system – form a horizontal stratification or domain of peaceful change in world politics, especially during the period of potential order transition (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Dimensions of peaceful change

It is worth noting that IOs are not always agents of peaceful change. Frédéric Mérand and Vincent Pouliot in one of the rare examinations of the peaceful and not so peaceful contributions of international institutions for change, argue that they can promote peaceful change by: (i) constraining state behavior, especially violent behavior; (ii) fostering norms of peaceful conduct; (iii) promoting interdependence and trust; and (iv) generating social interaction and collective identities. However, institutions can inhibit peaceful change by: (i) locking in the status quo; (ii) producing exclusion; and (iii) generating new forms of struggle.Footnote 55

An unvarnished praise or criticism is not valuable for assessing the role of IOs in change in a balanced manner. IOs have contributed to change, but they are not always peaceful. IOs have caused stagnation and non-movement of alternative courses of action in areas where timely action was needed. They also many a times have worked on behalf of the powerful states.Footnote 56 Many a times IOs have contributed to much structural violence, especially when they approve economic sanctions that have killed thousands of innocent and vulnerable populations in target states, and not brought about much positive change in regions such as the Middle East. Iraq and Iran are examples of IO-led sanctions regimes hurting millions of innocent people. As John Mueller and Karl Mueller point out, “If the U.N. estimates of the human damage in Iraq are even roughly correct … [the] economic sanctions [by the UN] may well have been a necessary cause of the deaths of more people in Iraq than have been slain by all so-called weapons of mass destruction throughout history.”Footnote 57 These sanctions and carpet bombing have many similarities.Footnote 58 But wishing IOs away as inconsequential actors in international relations is not accurate or useful for understanding world politics other than for polemical debate purposes.

Even the argument that IOs need hegemonic powers for their creation and maintenance is not always supported by evidence. The creation of the EU, ASEAN, APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation), and SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) all happened without the direct involvement of the most powerful states although the role of political leadership from powerful states cannot be ignored either. As Oran Young points out, there are three types of international leadership in regime formation: structural leadership, entrepreneur leadership, and ideational leaderships.Footnote 59 Although material power is critical for structural leadership, the other two types of international leadership might or might not be directly associated with power. Therefore, middle and small powers have been able to use these two types of leadership to initiate changes and reforms within IOs as well as through IOs for more changes in the international order. Similarly, some of the arms of the UN, such as the UNESCO, have been on the critical knife of the US, but have survived, even in crisis.

In today’s complex world, it is unimaginable for interstate relations to operate without the presence of IOs, and in that sense, IOs have become a constitutive component of global governance in the current order. Although many of them were created by powerful states, they are playing an independent role in shaping state interactions as well as the future international order transition. It is the responsibility of states to make IOs more effective as agents of peaceful change, which they often ignore. The ongoing global climate crisis, increased US–China rivalry, the War in Ukraine, the Israel–Hamas war as well as the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic crises of the late 2000s and early 2010s illustrate the continuing importance of IOs in fostering peaceful change but also their challenges in delivering peaceful change in times of crisis. In a world of increasing geopolitical contestation, the strategies of enhancing the effectiveness and fairness of IOs will be critical for encouraging peaceful change in the international order. Identifying these strategies involves analysis of which lessons to learn from past experience, including successful cases such as decolonization and the creation of the post–World War II Euro-Atlantic order as well as failed attempts such as the League of Nations. In particular, nation-states need to strengthen both procedure and performance legitimacies of the IOs in global governance,Footnote 60 and to extend legitimacy beyond liberal elites. Legitimacy and collective legitimation functions have been essential for states operating in contested arenas where they have sometimes made choices against their own declared national interests. Trade disputes and rulings by WTO have been observed by states even when some such acceptance could hamper their short-term interests.

The Liberal Order and Peaceful Change through International Organizations

As the third key pillar of the LIO, international institutions form a very significant topic of liberal discourse and solutions to collective action problems. We have witnessed many roles that IOs play in either enhancing or reforming the LIO, and they all have relevance for the minimalist and maximalist changes we defined at the outset. For example, from a rationalist perspective, if we treat mutual cooperation as one of the minimalist changes among states competing for survival under anarchy, international organizations can foster state cooperation by reducing transaction costs, providing focal points, and addressing collective action problems, as well as building trust among states.Footnote 61 There are several other functions rationalists ascribe to international organizations. These include the promotion of global economic cooperation and global welfare, such as tariff reduction through trade negotiations, elimination of protectionism, and encouragement of corporations to invest in different parts of the world, diversifying investments and increasing growth.

In addition, IOs can help promote “shared norms and values,” especially liberal values, including pacific settlement of disputes, “reciprocity, multilateralism, and the rule of law” and the furtherance of human rights according to Constructivism. As some scholars suggest, OECD countries have taken efforts in promoting these liberal norms and values as a “measure of international legitimacy” or “rightfulness” through various international organizations for decades. Consequently, the LIO has “acquired a normative quality that will … mitigate logics of consequences and promote logics of appropriateness” in world politics.Footnote 62 Finally, IOs are needed to provide assistance to “victims of international politics” including victims of poverty, hunger, environmental disasters and epidemics/pandemics, and war and conflict, including civil conflicts.Footnote 63 These are as former UN secretary general Kofi Annan alluded to “problems without passports.”Footnote 64 In order to address or solve these problems, the fundamental norms and identities of the LIO that govern the interactions among political entities – state actors and non-state actors, including IOs – might have to be changed in world politics.

These liberal goals are sometimes presented by defenders without examining how exactly IOs perform these functions, or what externalities or unintended consequences they produce as agents and sites of continued stratification and inequalities.Footnote 65 International organizations become a source of inequality and hierarchy among states because the rules and norms are embedded in the “international pecking orders” that create exclusive clubs among states in the international system.Footnote 66 It has been argued that “a world order in which developing countries are norm-takers and law-takers while Westerners are the norm- and law-setters, interpreters and enforcers will not be viable because the division of labor is based neither on comparative advantage nor on equity.”Footnote 67 In other words, IOs are associated with inequality and international hierarchy among member states as well as between member states and nonmembers.Footnote 68 Therefore, it is rational for dissatisfied members to initiate changes inside and outside the existing institutions so that the inequality problem can somehow be addressed, if not resolved. That is why we have witnessed internal adjustments and changes of existing IOs, such as IMF’s quota reform. In addition, some developing countries have also become creators or shapers of new norms through their activism in the UN and other forums such as BRICS and G20.Footnote 69 Recently, dissatisfaction with international governance has become more prevalent within the old ‘West’ as marginalized groups on both the left and (in particular) right sides of the political spectrum as well as some national elites have rebelled against international rule of law.Footnote 70

Expectations and the actual outcomes could vary, and much work is needed to examine performance and outcomes, short and long term, and see the changes brought about by IOs in terms of producing lasting change in a peaceful manner. Liberal goals need not bring common prosperity to all as free trade, especially in the globalization era, has generated many distributional challenges and income inequalities, producing “winners” and “losers.” Liberal economic institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank have been criticized for making many poor nations poorer and trapping them in extreme poverty and indebtedness, although some have used the international economic support wisely.Footnote 71 Michael Barnett and Martha Finnemore suggest that international organizations are autonomous actors in shaping states’ interests as well as in generating institutional changes. International organizations, therefore, are bureaucracies that are obsessed with their own rules, producing unresponsive, inefficient, and self-defeating outcomes.Footnote 72

Realist critics have tended to focus on temporality and power dynamics in IOs, ignoring their role in change. If anything, they reinforce hegemonic powers’ aspirations and may in fact contribute to conflict in the system.Footnote 73 IOs and other regimes are the creation of hegemonic powers, and when these powers decline, IOs also decline. Robert Gilpin argues: “The particular interests that are most favored by the social arrangements tend to reflect the relative powers of the actors.”Footnote 74

This has been a contested argument as the title of Keohane’s book, After Hegemony attests. More importantly, IOs have their own life cycles with or without the presence and support of a hegemonic power and may indeed contribute to peaceful change, whether it is for good or bad.Footnote 75 Examples include the constant criticism of and underfunding by the US of UNESCO and at times WHO. Despite this, they seem to survive and perform functions generating many opportunities for peaceful change and interactions among states. Accordingly, some scholars contend that the LIO has been institutionalized through various international organizations, regimes, institutions, and treaties. These institutions, international organizations in particular, are often seen as “sticky” because they can persist against both exogenous and endogenous shocks.Footnote 76

Data on IOs and their deaths suggest that power politics is only one factor for their demise. According to one study, out of the 561 IGOs created between 1815 and 2005, some 218 have demised constituting a 39 percent of death rate. Some collapsed after their original purpose due to lack of funding or function, while others due to wars and conflicts, or when the founding treaties expired. This study demonstrated that “i) overall mortality is high among IGOs, ii) states often prefer to create new IGOs as opposed to reforming existing ones, and iii) having a large and heterogeneous membership is associated with greater organizational survivability.”Footnote 77

Even if IOs are created and shaped by powerful actors, these can produce ideas and norms that can outlast the specific institution and the powerful states themselves. For instance, the idea of “national self-determination” originally intended for European empires became a global phenomenon and has been powerfully present since it was proposed in President Wilson’s 14 points in 1919. As Christian Reus-Smit argues, the self-determination norm has become a fundamental institution of the international order, which constitutes a maximalist peaceful change in the international system in the mid twentieth century.Footnote 78 Collective security is another idea that survived the League of Nations and somehow revived through the United Nations despite numerous criticisms on the practice of the idea in world politics.Footnote 79 For the current LIO, it has evolved over time and experienced “peaceful change” because it can somehow absorb many “intrusive” ideas raised by states and IOs. For example, the norm of “responsibility to protect” was originally advocated by the African Union, although the practices of the norm have been contested by many African countries.Footnote 80

Organization of the Volume

The volume is organized into four main parts. Part I introduces the aim, key conceptual definitions, and general themes of the volume (this chapter).

Part II contains chapters directly addressing the paradigmatic understanding of the importance or limitations of international organizations as agents for peaceful change. Liberal, Realist, Constructivist, English School, and Rationalist explanations are discussed. In Chapter 2, partially drawing on English School ideas, Arie Kacowicz argues that great power management of international order depends on how they perceive legitimacy to their status accrued through the creation and maintenance of international organizations and how much normative consensus exists among them on the rules of the game, all facilitated by a stable and recognized distribution of power. Using the English School as a theoretical prism, Kacowicz discusses the historical evolution of great powers’ efforts to manage their relations, foster international orders, and promote (or hinder) peaceful change in international relations through their use (and abuse) of international organizations. Focusing on international organizations and peaceful change over the past 200 years, the chapter shows how the evolution of mechanisms such as the Great Power Concert and Collective Security and the role of the UN Security Council offer a historical context and background for the present-day changes. Although the main focus of the chapter is on great power efforts at peaceful change through international organizations, Kacowicz also discusses how great powers often stymie attempts at peace and peaceful change through violent behavior.

In his comprehensive examination of Liberalism and its contributions to peaceful change, John Ikenberry argues that at various critical junctures, liberal internationalism used international institutions to create cooperative international orders as a way to manage the twin problems of anarchy and hierarchy in which they were entangled themselves. These efforts were not just manifestations of power politics, as realists contend, but they were efforts by Liberals to coordinate policy dilemmas generated by growing interdependence and the need for openness arising from liberal ideals on democracy and economic competition.

A strong defense of international organizations and peaceful change through a Constructivist lens is offered by Trine Flockhart. She acknowledges that paradigmatic IR, whether Realism, Liberalism, or Constructivism cannot fully account for change, especially peaceful change in international relations. However, Constructivism as a social theory (rather than as an IR theory), offers a more inclusive meta-theoretical approach that can explain structure and agency and “the reflective processes of agents.” Such an approach can offer a better handling of a range of agent–structure relational aspects and change itself. She examines the relationship of international organizations and peaceful change using this refined Constructivist approach with the aid of the case study of NATO on how the military alliance has contributed to peaceful change.

Duncan Snidal offers a cogent analysis of the rationalist foundations of international organizations and their search for peaceful change. He explores the different roles of institutions in maintaining order versus promoting change by differentiating between two broad categories of FIGOs (formal intergovernmental organizations) and IIGOs (informal intergovernmental organizations). He argues that FIGOs mainly aim to instantiate and maintain the existing order. By contrast, IIGOs as “soft” informal institutions can be used to deal with larger transformational change. Therefore, he suggests that “the question is not whether international organizations produce peaceful change but rather what form of international organizations states should choose in pursuit of peaceful change under different circumstances.”

In his Realist criticism of international institutions, Christopher Layne argues that the liberal rule-based international order is little more than Pax Americana. It was constructed by the United States after World War II and continues to depend upon US military and economic power. Following the Cold War, the United States extended both the geopolitical reach and the ideological ambitions of this order, but with the rise of China and the decline of US power and the ability to act as a hegemon and manager of the international political economy, this order is in crisis. Layne finds that existing IOs are unlikely to secure a peaceful change from the Pax Americana to the next international order. Consequently, the risk of a great power war is increasing.

In Part III, we explore selected, key international organizations and their track record in obtaining peaceful change. These are the UN General Assembly, the UN Peacekeeping Operations, the UN Environment Program, the WHO, the WTO, and the G20. Although G20 is not exactly the same type of organization as the others examined here or as we define them, it gives us a variation by way of a more informal institution and one that also has only flexible bureaucratic structures, altering from one location to another. By focusing on the historical developments of the organizations examined, contributors explore the different stages in the lifespan of an international organization and discuss when and how IOs facilitate or even produce peaceful change.

In her chapter, M. J. Peterson explores the ways through which the UN General Assembly pursued maximalist goals for peaceful change in key areas such as decolonization, human rights, disarmament, and the economic well-being of poorer countries. The achievements have been mixed, but still, the ambitious agenda of the UN General Assembly, unlike the Security Council, offers much for humanity’s search for deep change without violence. To Sarah-Myriam Martin-Brule, UN peacekeeping has a contrary result than expected in terms of peace and peaceful change. It has helped foster international and regional peace, but in many situations, it has not helped the reduction of internal violence where peacekeeping operations take place. Here, peace operations often underpin the status quo, generate new forms of political struggle, and produce exclusion. Still, by negotiating and drafting mandates for peace operations, great powers may identify common interests and objectives, which facilitate implementation as well as future cooperation.

Focusing on the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Maria Ivanova explores the extent to which the organization has lived up to its original purpose to catalyze transformational and peaceful change in environmental governance. She finds that while this is still a work in progress, UNEP is overall a success story advancing peaceful change through changes within the organization, its interactions with other international organizations, and by it fostering power transition within the global environmental governance arena. She shows how this is achieved through the interaction of organizational developments, small states, and great powers. As Kelley Lee argues in her chapter, the WHO’s evolution as a functionalist institution as envisioned by its founders has contributed to many key areas such as “conducting disease surveillance, monitoring and reporting; issuing disease control and treatment guidelines; reviewing evidence on a comprehensive range of health topics; and setting international standards and nomenclature.” The politicization of WHO was a result of structural conflict involving Global North and Global South countries in the 1980s, but it has now assumed a new dimension with China’s increasing role in the organization and the US/Western efforts to curtail it. Despite all these, WHO has many feathers to its cap, such as global efforts to eradicate smallpox, polio, and many other diseases, which caused immense misery to millions especially during war times. The COVID-19 crisis stretched the organization’s capacities, but without an alternative to it, WHO still remains a crucial element of global cooperation in the containment and management of diseases.

The WTO is Aseema Sinha’s focus. She argues that the current crisis in the international trading order is a crisis of success. In the early phases, WTO stimulated domestic change, which created domestic backlash for maximalist change as IOs create distributional conflict. The 1990s and 2000s were successful in realizing post–Cold War hopes of peaceful change in the international political economy. Conflicts were managed within institutions and emerging powers were accommodated in a way that allowed them to rise peacefully. However, since the late 2000s, populist sentiments in the West combined with rising powers’ increased use of the WTO trading system for their own ends have changed the discourse on free trade and pushed the world toward de-globalization.

The final chapter in this part is on G20 by Andrew Cooper. Cooper uses a technique of examining the relative absence of attention to G20 in the extant IR literature to show how it has contributed to peaceful change, especially the partial democratization of international governance and its sometimes not so stellar performance. He argues that despite internal differences and an uneven development, G20 has proven to be a valuable institutional platform for managing bilateral tensions among leading states.

In Part IV, we offer two concluding chapters. One is a critical treatment of positivist enterprises in IR discussing the implications of applying conventional IR to the relationship between international organizations and peaceful change. Ian Hurd argues for an interpretivist approach to peaceful change and IOs reflecting upon possibilities of what might arise rather than looking for fixed relations among variables. Chapter 14 by Alice Chessé critically evaluates international organizations and their role in obtaining or promoting peaceful change and revisits the central concepts and definitions of the introduction in the light of the contributions to the volume. The chapter also responds to Hurd’s criticism while defending the need for sustained research on this neglected area in IR using different methods and approaches, positivist, interpretivist, and critical, and we favor all the three by way of promoting eclecticism in this research area.Footnote 81

This volume does not make the relationship between international organizations and peaceful change an unvarnished positive one or in a unilinear direction. It offers critical analyses of the positive and negative roles international organizations exert on change in the global arena and examines how, when, and why international organizations matter for peaceful change. The chapters unravel valuable insights on the ways through which international organizations act or contribute as agents of change as well as defenders of status quo; how international organizations galvanize or challenge existing hierarchies and inequalities; and how they facilitate meeting new global challenges such as the pandemics and climate change peacefully. More importantly, they evaluate the generic issues of how international organizations interact with power politics in affecting the likelihood and content of peaceful change, the type of “peace” – whether it is minimalist, maximalist, or in-between categories – and the conditions under which they occur. Insights are offered on the conditions for incremental change within organizations and reforms or when they become “sticky” and unable to adapt to changing circumstances and their implications for global change. Finally, this volume offers ideas on the normative effects of international organizations in terms of fairness and legitimacy, while fostering change in world politics. Our larger aim here is to engage the highly developed research area of international organizations and link them to change, in particular peaceful change in world politics.