Since the onset of the global financial crisis and the great recession in 2007–9, we have entered an age of democratic backsliding.Footnote 1 The countries affected not only include weak democracies considered to be at risk, but also countries like Poland and Hungary, once considered regional leaders in the process of democratization in postcommunist Europe. The purpose of this contribution is to understand how two countries considered the biggest democratic successes in postcommunist Europe became its most notorious cases of democratic backsliding.

Unlike past waves of democratic failure, the episode has not been marked by spectacular disjunctive events like putsches, coups, civil wars, and seizures of power.Footnote 2 Instead, there has been a decline in the quality of democracy, often led by leaders who have won democratic elections. A set of facilitating structural conditions—recession, increased inequality, peak immigration, austerity, and rapid social change—combined with a politics of exclusion and fear practiced by populist politicians has led to challenges to democracy in both established (the United States, Great Britain, India) and newer democracies (Bolivia, Brazil, Venezuela, Philippines, Nicaragua, and Turkey). These populist leaders give voice to disenchanted citizens who feel cheated by corrupt elites who have stacked the system in their favor.Footnote 3 Once they have secured executive power bolstered by parliamentary majorities, they then move to curtail horizontal checks and balances, gutting judicial oversight and other autonomous regulatory agencies. Many also try to undermine social accountability by passing legislation or engaging in informal practices that undermine the ability of civil society and the independent media to impose costs on office holders. Such practices are now widespread in Poland and Hungary.

Backsliding does not always lead to regime change. In the two cases explored here Hungary is increasingly seen as a failed democracy. Such electoral authoritarian regimes continue to hold elections but tip the balance in favor of the incumbent by resorting to what Andreas Schedler has called the “menu of manipulation,” and what Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way have called “an uneven playing field” of electoral competition.Footnote 4 Unlike the classic accounts of the rise of electoral authoritarianism which are often the product of failed transition, Hungary's path came via backsliding. Backsliding does not always entail a full-blown descent into electoral authoritarianism; in some cases it registers only as a reduction in the quality of democracy by weakening democratic norms and institutions. Most consider Poland to be in this situation.

Eastern Europe has not been immune from such trends. There are earlier cases of fledgling democracy that reverted to authoritarianism, albeit in postcommunist forms (Russia, Belarus) or other cases which have alternated between democracy and electoral authoritarianism (Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Moldova). The current pattern of backsliding in the region was unexpected because it afflicted two states, Hungary and Poland, which initiated the regional process of democratization in 1989, were long seen as regional leaders in the building of liberal democracy, quickly joined the European Union (EU), and were even considered consolidated democracies.Footnote 5

Another reason why backsliding in Poland and Hungary is particularly unsettling is that the responsible parties, the Fidesz—Hungarian Civil Alliance in Hungary and Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland are established parties whose origins lie with the democratic opposition under communism.Footnote 6 Both had track records as democratic parties that contested power, participated in government, and stepped down when they lost elections. In other cases of democratic backsliding in the region the leading actors have commonly been drawn either from the former communist power-elite or come from novel postcommunist parties (Borisov in Bulgaria, Babiš in Czechia, or Vučić in Serbia).Footnote 7

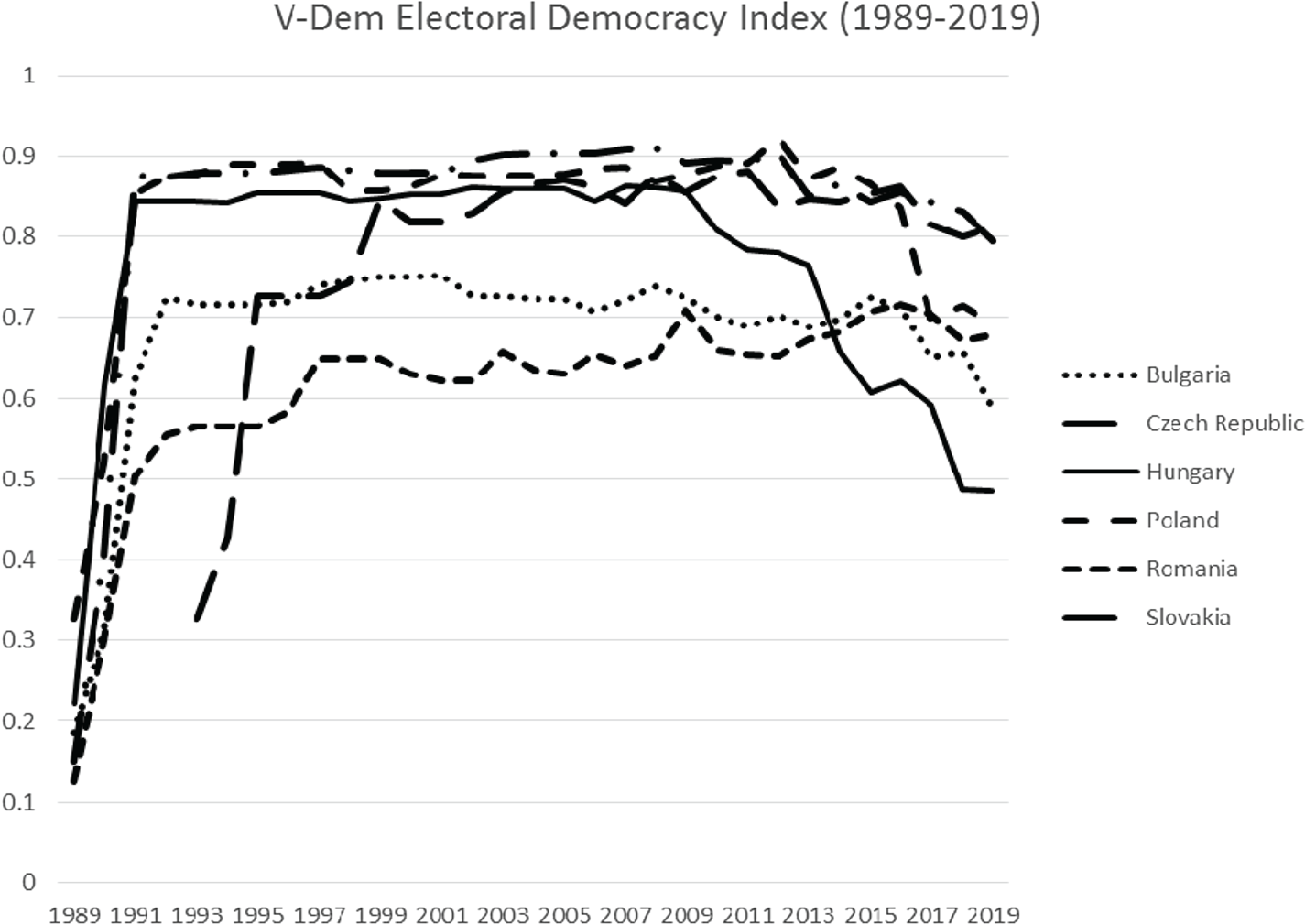

The deterioration in democracy in Poland and Hungary is plain to see in Figure 1, which plots the electoral democracy index from the Varieties of Democracy project for those two countries plus Czechia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania. Along with Czechia, Poland and Hungary rapidly democratized while the other three were slower. While Slovakia also attained a high level of democracy, albeit later, both Romania and Bulgaria achieved more moderate levels. While the figure makes clear a general deterioration of democracy in the region, in Hungary and Poland it is much more precipitous, with both falling to levels in the neighborhood of Romania and Bulgaria, with Hungary now in the basement.Footnote 8

Figure 1: Democratic Backsliding in East Central Europe

To reiterate, the central question that this article seeks to answer is how and why democratic backsliding occurred in Poland and Hungary, countries whose previous rapid and deep democratic progress should have made them “least-likely cases” for backsliding. To understand why this occurred I return to the literature on democratic transition and its hypothesized impact on long-term democratic stability. Two different literatures, one that emphasizes the role of elite bargaining and the other which emphasizes the role of contentious transitions both suggest that Poland and Hungary had good prospects for democratic consolidation. In the remainder of this article I will (1) review these literatures on contentious and accommodative transitions; (2) discuss the cases of Poland and Hungary and show that they are not readily reduced to cases of negotiated or contentious transition; and (3) argue that the combination of negotiation and contention, in concert with changing structural conditions in which both countries were embedded, contributed to democratic backsliding. In doing so I hope to show how the reevaluation of past theories and the reinterpretation of events in that light help us make ex post facto sense of unexpected reversals as we have observed in Poland and Hungary.

Paths of Extrication and Democracy

Democratization in the late twentieth century included a large number of non-violent transitions that involved negotiations between authoritarian incumbents and oppositional elites. There was a consensus in the foundational literature on democratic transition, based on the experiences of Spain and Latin America, that successful democratic transitions were predicated on implicit or explicit understandings between the soft-line faction of the authoritarian incumbents, and the moderate wing of their oppositional challengers.Footnote 9 Further, there was the expectation that with the “crafting” of the right set of institutions through elite consensus, stable democratic outcomes were probable.Footnote 10

The literature on modes of transition moved the discussion on the effects of transition on long-term democratic stability beyond the content of the settlements to also encompass the means by which they were transacted.Footnote 11 Particular attention was paid to “the identity of the actors who drive the transition and the strategies they employ.”Footnote 12 The questions of whether authoritarian incumbents or their challengers were ascendant in the transition process and whether it involved a greater degree of accommodation or confrontation were seen as critical. Over time, this debate focused on whether transitions were pacted, negotiated, and controlled at the elite level, or contentious, where popular mobilization played a role in constraining elite power. I will argue that the Polish and Hungarian transitions do not easily fall into either type, which helped to structure similar patterns of post-transition politics that help us understand their unexpected paths to democratic backsliding.

I conceptualize the extrication from communism as a critical juncture for regime formation that created twenty years of democratic stability in both Poland and Hungary. This stability was disrupted, quite unexpectedly, by the incorporation of both countries into the EU, and by two external shocks, the great recession of 2007–9 and the European refugee crisis of 2015. In this discussion I will focus explicitly on the impact of the mixture of contention and accommodation in their democratic transitions, building on, but fundamentally revising the insights of the modes of transition literature. With benefit of hindsight, I will show that this dichotomy was an oversimplification that with rethinking helps to explain the vulnerability of democracy in both countries.

In thinking about the legacies of extrication from authoritarian regimes, partisans of theories of contentious versus accommodative processes disagreed strongly over which pattern contributed to democratic success. Early on, many believed that accommodation facilitated durable democracy. Michael Burton, Michael Gunther, and John Higley argued that negotiated elite settlements led to consolidated democracy by creating consensus on norms and rules, promoting legitimacy, limited government, moderation, and the effective channeling of popular demands.Footnote 13 In a variant of this argument, Gretchen Casper and Michelle Taylor argued that difficult negotiations that resolved substantive differences between incumbents and the opposition stood a better chance of making real democratic progress. When the opposition pushed hard for real democratic concessions this increased their popular support, causing incumbents to compromise and adapt to the emerging democratic environment. Failure of the opposition to take a strong stand would allow the authoritarian incumbents to structure post-extrication institutions to their advantage and delay or even block the full emergence of democracy.Footnote 14

In contrast to this, others stress contentious transitions as the key to long-term democratic stability. Stephan Haggard and Robert Kaufmann show that in cases where democratic transition includes distributional conflict, the quality of democracy improves in the long term.Footnote 15 This parallels Robert Fishman's paired comparison of Spain and Portugal, where in the long term Portugal's revolution created a higher degree of democratic responsiveness than Spain's elite bargaining.Footnote 16 Dawn Brancati demonstrates that the size of democratic protests has a salutary effect on the depth of democratic reform.Footnote 17 Both Donatella della Porta and I argue that popular participation and contention in episodes of democratization create better odds for success in transition and better democratic outcomes.Footnote 18 What all these studies stress is how mobilized citizenries block the ability of elites to channel reforms in ways that allow them to either maintain the status quo or convert their power into new forms of privilege.

Different analysts have discussed the Polish and Hungarian transitions as accommodative because both involved roundtable negotiations as critical components of the process, while others argue they were contentious because the oppositions in both countries were based on networks of civil society organizations that had emerged prior to transition under late communism. While the literature hypothesizes different outcomes on the basis of whether extrications from authoritarianism are accommodative or contentious, neither Poland nor Hungary is easily characterized as either. Both cases involved elements of accommodation and contention and phases in both processes could be characterized as one or the other. In the next section, I will explore how the categories in this literature do not neatly map onto Poland or Hungary. Further, I will then argue that this combination of negotiation and contention created conditions in the longer term that proved conducive to democratic backsliding despite early promising starts.

Retrospective Evaluation of the Extrications in Poland and Hungary

Quite often the Polish extrication of 1989 is treated as a prototypical negotiated transition to democracy.Footnote 19 This is because of the Roundtable Agreement of April 1989 in which the communist party relinquished its monopoly over organization and information and the terms of electoral competition were established. The Hungarians also had Roundtable talks, but they broke down before completion and the final shape of the rules for extrication were determined by a plebiscite due to the recalcitrance of elements in the opposition to adopt rules that favored the communist incumbents. The Hungarian extrication is thus presented as having both elements of accommodation and extrication while the Polish process is seen as accommodative.Footnote 20

This consensus is due for reconsideration, however. The Polish extrication is mischaracterized as simply accommodative. First, the initiation of the extrication process from communism and its ability to affect true democratic change was a function of the strength of the Polish opposition. The Solidarity opposition that negotiated with the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) in 1989 traced its roots back to 1976 with the emergence of several precursor organizations to the union, its sixteen months of legal existence in 1980–81, and its persistence as an underground opposition from Martial Law until its relegalization.Footnote 21

The Roundtable in Poland was triggered by a strike wave in 1988 that demonstrated that the regime's efforts to stabilize the country following Martial Law had failed. The regime was prepared to make wide-ranging concessions to draw Solidarity into a reform process. It relegalized the union and invited it to Roundtable Negotiations in March 1989. Under the terms of the agreement signed in April, competitive elections were scheduled for June, but with substantial guarantees for the ruling communists and their allies. The PZPR, the United Peasant Party (ZSL), and Democratic Party (SD) were guaranteed two thirds of the 460 seats in the Sejm, with the remainder fully contested. A second chamber, a Senat, was created and its 100 mandates were fully contested. The accord also created an executive president, elected by the joint membership of the two houses. Given the guarantees, the first occupant of that office was expected to be chosen by the PZPR. It was also expected that the first Prime Minister would come from the communist camp.Footnote 22

Things did not go according to plan. Ultimately, all contested seats, save one in the Senate, were won by the Citizen's Committees created by Solidarity and many seats reserved for the communists were left unfilled because of insufficient vote totals. The weak performance of the PZPR led the ZSL and the SD to defect from their efforts to form a government. A compromise was then negotiated for a national unity government led by a Solidarity Prime Minister, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, in return for allowing the PZPR's leader, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, to assume the presidency. With this failure of the Roundtable to live up to its terms, the Polish extrication path once again moved from negotiated to contentious.

Once the terms were breached, Solidarity activists continued to push against the remaining guarantees for the communists that stood in the way of full democracy. A cadre of activists left out of the government, centered on Solidarity's leader, Lech Wałęsa, continued to push for more radical reforms, whereas the Mazowiecki government continued to stress abiding by the terms of the previous negotiated compact. The pressure from below proved too much to resist and a second set of negotiations led to direct election of the president in 1990, a contest won by Wałęsa, and the replacement of the Mazowiecki government. This new government, in turn, called fully competitive legislative elections in 1991.

The extrication in Hungary was similarly contentious, but less protracted. As the second to move, the Hungarians faced less uncertainty about Soviet intentions. The political opposition in Hungary was not as developed as its Polish counterpart. It supported an alternative uncensored public space, but was more modest in its outreach to society at large. However, late in the tenure of the communist regime it showed an increasing capacity to demonstrate and stage other public events on national anniversaries and on issues such as ecological destruction, the rights of the Hungarian diaspora, and peace. It was divided between a more liberal/social democratic Budapest-based component and a more provincial Christian democratic wing. These two wings crystalized into competing proto-parties—the Free Democratic Union (SzDSz) and the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF). Another important actor was the liberal student milieu organized as the Young Democratic Union (Fidesz).Footnote 23

Reading the writing on the walls, the ruling Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (MSzMP), which had a sustained history of reformism and back-tracking, took a proactive stance after the removal of longtime leader János Kádár. They made contact with the opposition and tried to draw them into the process of reform from a position of strength. Their leading figure, Imre Pozsgay, had good relations with the MDF, but failed to draw them into a durable cross-camp alliance in a gambit to extend his power. Such overtures were rejected by the SzDSz and other elements in the opposition and the Roundtable Negotiations in Hungary broke down over the question of whether a new executive president, to which Pozsgay aspired, would be directly elected prior to parliament, or would be appointed by a freely elected one. SzDSz then mounted a petition campaign for a referendum to resolve the issue and the parliamentary elections were held first and selected the president. In those elections the MDF won a plurality and formed a government.Footnote 24

Impact on Post-Extrication Political Actors

Both the Polish and Hungarian extrication processes included a combination of intense contention and negotiation. Of all the post-communist cases, it was in these two that the opposition both had a relatively developed organizational capacity and the ability to strategically protest in struggles with the party-state. The ability of the communist incumbents to negotiate and persist in the face of the uncertain outcomes of those processes showed that they still had the ability to evolve and respond effectively to rapidly changing political environments. Their ability to do so combined with the resource advantages they enjoyed as ruling party successors allowed them to expunge hardline elements, make new allies, and remake themselves as reformist social democratic parties.Footnote 25 Their effectiveness was attested to by their ability to rebound, win elections, and form governments in 1993 in Poland and in 1994 in Hungary.

The recovery of these parties was consequential for subsequent developments. Both the Polish and Hungarian postcommunist successor parties, the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) and Hungarian Socialist Party (MSzP), adopted programs supporting democratic and market reform, and membership in NATO and the European Union. This also meant that the ability of the opposition to distinguish itself from the main postcommunist successor party on programmatic grounds was now highly constrained.

The literature on transitions, especially if one considers the Polish process as one that extended from 1989–91 and the breakdown of the Hungarian Roundtable, overstates the unity of the opposition to the regime. The account above highlights important areas of contention within the opposition in both countries during the extrication process on tactical and temperamental grounds. Further, once extrication was complete, the need for solidarity by the opposition against the regime or its successors was no longer necessary for political survival. This led to a diversity of post-oppositional parties that competed with each other and the communist successor parties. The pattern of electoral competition and government formation in both countries settled into alternation between postcommunist-led and opposition-led coalitions. This also meant that in order to form governments post-oppositional political actors needed to distinguish themselves to win elections, lead governments, and claim portfolios in the cabinet.

The nature of the contentious but negotiated extrications led to the opening up of a specific discursive space into which political actors willing to take what has been labelled a memory warrior stance hostile to the transition process were able to cultivate a stable constituency and compete for power in durable fashion following the extrication process.Footnote 26 The strategy of the memory warriors was to discredit the foundation of democracy by claiming that the negative effects of communism persisted despite the “purported” transition to democracy, thus delegitimizing the current system and political actors implicated in its origin. In this rhetoric a true democratic transition did not take place because a corrupt deal was struck between the communists, who were frenetically trying to defend their power and privilege as the system collapsed, and the members of the opposition who negotiated with them, purportedly continuing to collaborate with them in a pact of mutual enrichment. This rotten deal denied the true fruits of democracy and economic transformation to “real” Poles and Hungarians.Footnote 27 This rhetoric strongly aligns with the notion of ideologically thin populism that partitions society into a corrupt elite, which takes advantage of some sort of invented, pure people who embody a purported general will.Footnote 28 What is unique about these populists, compared to others in the region, is that they emerged out of the democratic opposition as a consequence of transitions that combined contention and accommodation. Accommodation provided the grievance and contention provided a form of political capital conducive to pursuing it.

Five aspects of the Polish and Hungarian extrications gave rise to this discursive space conducive to a memory warrior stance vis-à-vis transition. First, the initiation of extrication via Roundtable Negotiations opened up the possibility to cast the outcome as a rotten deal in which part of the opposition and the communists divided the spoils. By their very nature negotiations necessitate compromise and the confining of maximalists to the sidelines. This opened the post-extrication order to the charge that it was an incomplete or corrupt revolution, which instead of creating a “true” democratic order enriched a select group of oppositionists who agreed to shield the interests of the communists for a share of the spoils. Second, the divisions on the post-oppositional side of the political spectrum provided incentives for the weaker political parties on the right to radicalize. In particular, the marginalization of maximalists provided no incentive for moderation. Third, the emergence and persistence of strong postcommunist social democratic parties made the pattern of alternation in power by post-communist and opposition-derived political parties possible. This lent some “face plausibility” to the rotten deal narrative inasmuch as parties often founded and staffed by former opposition moderates, as well as regime reformers continued to rule. Fourth, the adoption of the democratic, pro-market, and pro-western agenda of the opposition by the postcommunist successor parties created a highly constrained set of postcommunist policy choices from which voters could choose. This led many voters to give credence to the narrative that transition was crooked inasmuch as it offered highly constrained policy choices. Fifth, given the tradition of contentious political engagement which played a decisive role in their extrications from communism, the capacity of these societies for contentious politics provided the proponents of the rotten deal/incomplete revolution narrative other means to push their agenda even when they were marginalized from state institutions.

In Hungary, the actor that came to occupy this space was Fidesz, which soon after extrication became the main party of the Hungarian center-right and the most effective competition to the communist successor party, the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSzP). In Poland this was Law and Justice (PiS), led by the Kaczyński brothers, and the parties of the Solidarity right that preceded it. On several occasions these parties played an important role in the post-Solidarity party coalitions that alternated in power with the communist successor party, the Alliance of the Democratic Left (SLD). Until recently, PiS and its predecessors fared worse than their liberal and centrist competitors from Solidarity, such as Freedom Union (UW) and Civic Platform (PO). The discourse of both Fidesz and PiS even before the current populist backlash against liberal democracy had begun to incorporate interwar and wartime nationalist rhetoric back into the national political culture. This has been most explicit in Hungary, where Trianon has been rehabilitated as a defining national grievance and an ideology of shared fate with Hungarian minorities in neighboring states. This reassertion of elements from aggressive interwar nationalism has begun to explicitly include rehabilitation of reactionary, wartime collaborationist political actors, as well as Holocaust revisionism and denial. The reemergence of anti-democratic rightwing traditions, the condemnation of the democratic revolutions of 1989, the embrace of illiberalism, and the cultivation of new varieties of xenophobia have all worked to create a politics that is confrontational in opposition and ruthless in power.

The paths that both parties took to illiberal populism were somewhat different. PiS had lived in the discursive space of rotten revolution since its outset. Its origins go back to the war at the top in Solidarity over whether the union should challenge General Jaruzelski's legitimacy to hold the presidency. The Kaczyński Brothers founded their first party—the Center Compact (PC)—to support Lech Wałęsa's push for the presidency in 1990. After a moderately strong showing in the parliamentary elections of 1991, it led the Olszewski coalition government (December 1991 to June 1992), which unsuccessfully attempted to weaponize the secret police archives and rapidly fell from power.

They also took part in the Solidarity Electoral Action (AWS) alliance that brought Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek to power. The coalition joined together Solidarity liberals, moderates, and conservatives in a single government for one last time from 1997–2001. For the elections of 2001, the Kaczyński brothers broke with former allies and assembled a coalition of conservative factions into Law and Justice (PiS). Following another round of SLD rule, PiS emerged as the strongest party following the elections of 2005 and formed two short-lived governments from 2005–7. This election marked the eclipse of the SLD which found itself fully discredited by a series of corruption scandals. With this the postcommunist left lost its broad electoral appeal and a new Polish left of consequence has yet to reemerge. Electoral politics in Poland became a contest between post-Solidarity political forces.

In early elections in 2007 PiS lost to their more moderate, liberal Solidarity competitors, the Civic Platform (PO). PO ruled from 2008–15 and was the first party to win two consecutive parliamentary elections in Poland (PiS replicated this in 2019). It was during this period that PiS began its aggressive attempt to discredit the legacy of the events of 1989, in particular the Roundtable Negotiations. Initially the memory warrior stance was not an effective strategy for returning to power.Footnote 29 Why it became so and was able to support a successful illiberal backlash is a subject to which I will return following the discussion of Fidesz in Hungary.

Whereas PiS and its predecessors have occupied a relatively consistent position in the party spectrum in Poland, Fidesz has gone through a number of transformations in Hungary. It began as a party of liberal youth and then became a party of the center-right. After a disappointing performance in the elections of 1994, it changed its name to Fidesz—Hungarian Civic Party (Fidesz-MPP), breaking with the liberal international and growing more conservative over time. Unlike PiS and its predecessors, it was the most successful post-opposition party in its country. Whereas its competitors—the Free Democratic Union (SzDSz) and the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF)—faded, Fidesz transformed itself into a broad catchall party that consistently challenged the postcommunist Hungarian Socialist Party (MSzP) from the late 1990s throughout the 2000s. Since 2010 it has become a hegemonic party.

Viktor Orbán's first stint as Prime Minister came in 1998 to 2002 and was followed by two close losses to the MSzP in 2002 and 2006. Its loss in 2006 led to a further radicalization of Fidesz. The MSzP became the first party to win consecutive elections in postcommunist Hungary, but did so because the Prime Minister, Ferenc Gyurcsány, blatantly and knowingly lied about the state of the economy on the cusp of the election. It was at this point Fidesz began its transformation from conservatism to illiberalism.

From Reactionary Discursive Space to Illiberal Government

The path to this populist national conservative form of illiberal rule was made possible not only by the existence of the discursive space on the right, which I have argued was a product of the path of extrication from communism in both countries, but a set of facilitating structural changes as well. While both Fidesz and PiS were successful in occupying this space, taking a memory warrior stance against the exit from communism only brought them intermittent success until the 2010s. It is important to remember that prior to their current accessions to power, both had lost two consecutive general elections. Three structural developments were essential to their reversal of fortune. First, and quite counterintuitively, was the entry of both countries into the European Union in 2004. When countries seek accession into the EU their compliance with a set of legal and institutional norms (the Copenhagen criteria) are closely monitored and if they do not comply, they are not admitted. Once they are admitted into the EU their compliance with its fundamental norms is not subject to decisive enforcement mechanisms. At this point political actors who were reticent to break with EU political norms because of the cost were now freer to do so because the ability of member states to diverge from or even flaunt EU norms is much greater than that of candidate states.Footnote 30

Further, two recent exogenous shocks have also played an important role in making the memory warrior stance that both parties have assumed more valuable. Here, of course, I refer to the global financial crisis and the subsequent great recession (2007–9), and to the influx of a large number of Muslim refugees from failed states such as Syria, Libya, Iraq, and Afghanistan into Europe that reached crisis proportions in the summer of 2015. The narrative of failed revolutions in 1989 gained credence as global liberalism and EU membership, to which postcommunist Poland and Hungary had aspired, failed to protect Europe from a deep economic crisis and provoked a wave of xenophobia as millions of refugees flooded into the Schengen area. The rehabilitation of past national narratives of ethno-national xenophobia and arguments for protecting citizens against the uncertainties of the market gave both parties solid governing majorities that have allowed them to undertake their illiberal agendas.Footnote 31 The betrayed revolution memory warrior narrative was expanded to encompass global liberalism and the Brussels-based elite, and began to assert an illiberal European identity that poses traditional values in opposition to western decadence. Increasingly, politicians on the right depict Brussels as an imperial center that seeks to impose cosmopolitan values on the traditionally-oriented populations of the region.

Fidesz's slide into illiberalism began with its electoral loss in 2006. This led to an extensive campaign of civil disobedience and protest by Fidesz supporters and rightwing youth, who clashed violently with the police outside Parliament. It was during this period that the previously marginal ultra-right party Jobbik also began to gain strength. Protests began on September 17, 2006, after the release of a taped conversation where Prime Minister Gyurcsány admitted to lying about the state and prospects for the economy during the previous electoral campaign. Fidesz's ability to engage in this sustained campaign of protest was based on a long-term strategy of investing in civic organization at the grassroots level through the creation of an extensive network of Civic Circles following its electoral defeat in 2002.Footnote 32

Protest was concentrated in the main square outside Parliament and continued for over a month until October 23, the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. The protests garnered large crowds, an estimated 40,000 participants on September 18, demanding the resignation of the prime minister and the government. That evening a riot ensued when a group of protestors attempted to seize the national television studios, leading to dozens injured and extensive property damage. During this period there were also protests in smaller cities such as Miskolc, Szeged, Eger, Pécs, Debrecen, Szécsény, Békéscsaba, Salgótarján, and Nyíregyháza.Footnote 33

The largest protests occurred on October 23, the anniversary of the outbreak of the Revolution of 1956. Street battles ensued when the police attempted to clear Kossuth Square by Parliament in the early morning hours. This led to separate commemorations by the government and Fidesz at different locations in the city later in the day. Fidesz and its allies held a rally at the Hotel Astoria, an area of intense fighting in 1956, which drew a crowd estimated at 100,000. In his speech, Orbán drew parallels between government lies in 1956 and 2006 and accused the MSzP of being no better than the former ruling communists. Things got rough again in the evening with rioting and destruction of property, and the use of water cannons, tear gas, and rubber bullets by police. The demonstrations began to ebb from this point on, with one additional high point—a peaceful candlelight march to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution on November 4, 1956.Footnote 34

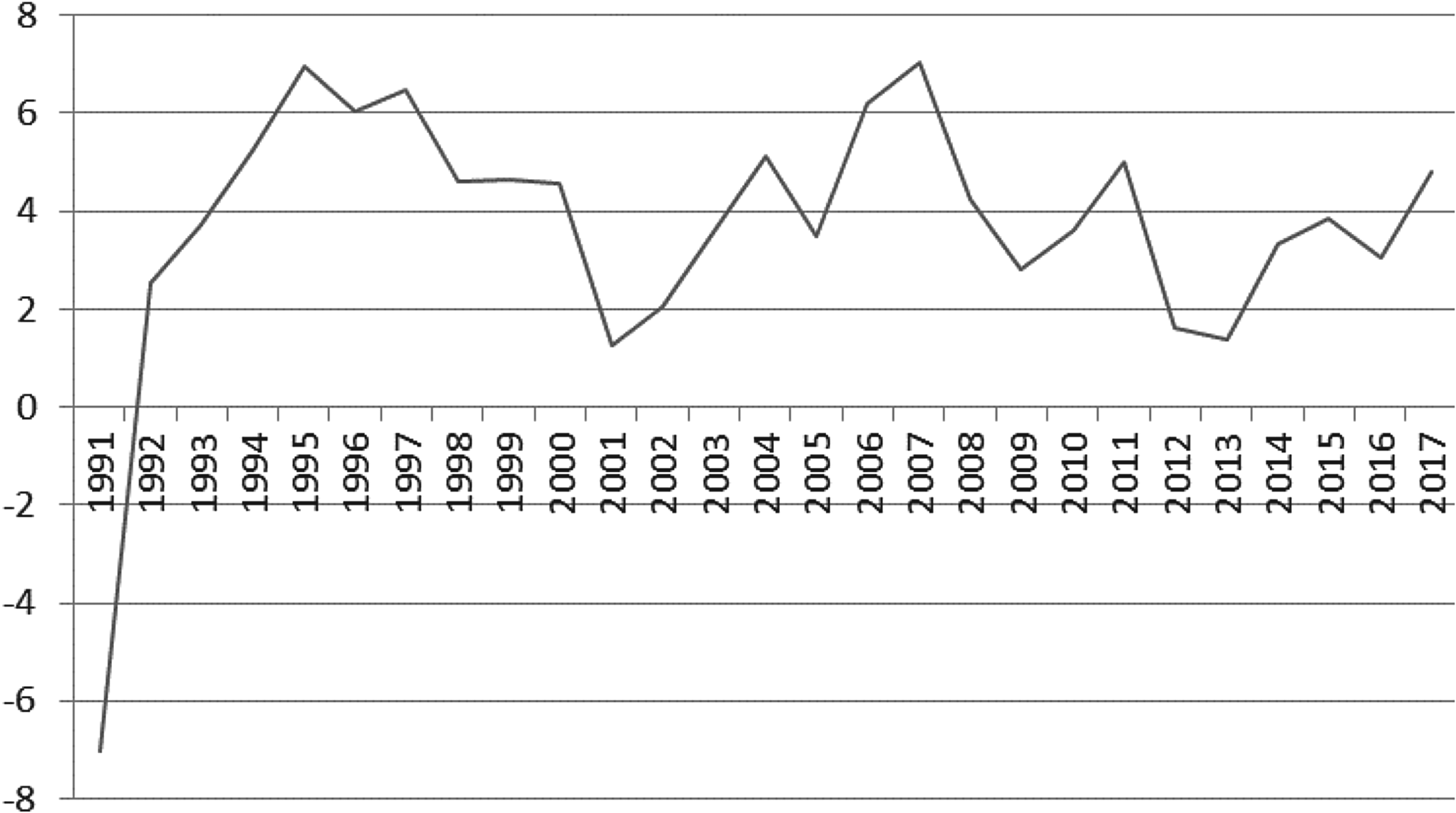

If we examine the impact of economic developments on the situation in Hungary, we see that the Hungarian economy went into recession somewhat earlier than the global economy. Figure 2 below shows that Hungary had already gone into a major growth slowdown in 2007 prior to the global meltdown in late-2008.Footnote 35

Figure 2: Percent Change in GDP per Capita Hungary, 1992–2017

The Gyurcsány government was able to weather the protests and the economic slowdown but when the full brunt of the economic crisis hit it resigned in March 2009 and was replaced by the minority government of Gordon Bajnai, composed of independent and MSzP ministers with the external support of the SzDSz. The cost to the MSzP was major; it lost a huge measure of its former support. In the elections to the European Parliament in June 2009, Fidesz took an outright majority, with the MSzP falling to 17 percent and losing five of its nine deputies. Most shockingly Jobbik, a rightwing populist party, participating for the first time, took almost fifteen percent of the vote. During this period the Hungarian right not only became dominant electorally, but began to dominate the public space as well. Béla Greskovits and Jason Wittenberg have collected protest and demonstration data for the period 1995 to 2011 and find that since the foundation of the Civic Circles, right-leaning Fidesz-affiliated civil organizations dominated protest activity between 2002 and 2010. They also show a major uptick in radical right activity starting in 2005 with a high point in 2006, which coincides with the rise of Jobbik as a major actor.Footnote 36

This all set the stage for Fidesz to return to power in the general elections of 2010. Running in coalition with the Christian Democrats (KDNP), they won 263 of the 386 seats in Parliament, giving them a constitutional majority. The MSzP came in second, falling to fifty-nine seats (a loss of 133). Jobbik was represented for the first time in the parliament with forty-seven MPs. Fidesz's constitutional majority gave them the power to begin to change the rules of government to suit their interests and in the period since they have moved to radically curtail the power of the judiciary, obstruct the autonomy of civil society, change the election laws to their own advantage, and consolidate their control over both the state and private media.Footnote 37 They have effectively weakened many important countervailing power centers that provide horizontal accountability. Fidesz received this constitutional majority based on a simple electoral majority of just over fifty percent in the first round of elections. The electoral system was designed to prioritize governability over representativeness, overrepresenting large at the expense of small parties.Footnote 38 Unintentionally, this aspect of institutional design meant to promote stability abetted Hungary's illiberal turn.

Fidesz-KDNP was able to repeat their electoral victory in 2014. After changing the electoral statute to increase their advantage at the polls, they received 133 of the 199 seats in the reformed parliament (just enough for a constitutional majority).Footnote 39 They did so on the basis of 45 percent of the popular vote, a mere plurality victory. Despite improvement in the economy (see figure 2 above) the ruling party was losing popularity. The regime moved to consolidate its position by developing its own indigenous ideology which it christened “illiberal democracy.” This was unfurled by Orbán in a major speech at Băile Tușnada in Transylvania, Romania, ironically at a summer camp to promote dialogue between Romanians and Hungarians. In the speech he attacked the west, calling its values decadent, devalued the role of society and its autonomy, declaring it to be a foreign agent and an enemy of the nation, and instead lauded the critical importance of a strong state in today's globally competitive world.

I would articulate this as a race to invent a state that is most capable of making a nation successful. As the state is nothing else but a method of organizing a community, a community which in our case sometimes coincides with our country's borders, sometimes not, but I will get back to that, the defining aspect of today's world can be articulated as a race to figure out a way of organizing communities, a state that is most capable of making a nation competitive. This is why, Honorable Ladies and Gentlemen, a trending topic in thinking is understanding systems that are not Western, not liberal, not liberal democracies, maybe not even democracies, and yet making nations successful. Today, the stars of international analyses are Singapore, China, India, Turkey, Russia.Footnote 40

Having declared himself an aspirational dictator, the biggest threat that Viktor Orbán faced was not from the liberals or the left, which were highly disorganized, beset by personality squabbles and petty differences, but from Jobbik, which positioned itself as radically right and more nationalistic than Fidesz. Polls in March and April of 2015 showed the popularity gap between the two parties closing. Some polls showed Fidesz's support falling into the twenties and Jobbik's climbing into the high teens, and even more ominously, Jobbik was beating Fidesz in some highly visible 2015 by-elections, taking an outright majority in the first round in one of them.Footnote 41

In this sense, the timing of the refugee crisis of the spring and summer of 2015 was fortuitous for Orbán and Fidesz. As refugees began to stream into Hungary in June, seeking asylum in richer states to the north, Orbán capitalized on the xenophobic fears of the population and began to build a border fence to control the influx, putting the Hungarian government in conflict with the EU refugee policy. The battles with Brussels over the border fence and refugee policy reestablished Fidesz's popularity, and since they have won both a third general election in 2018 and an EP election in 2019. They have also tightened their control over remaining centers of countervailing power, including the Office of the Prosecutor General, the State Audit Commission, the Electoral Commission, the state media, and the Constitutional Court.Footnote 42 They have also consolidated their hold on the private media sector and, after attacking Central European University and the Academy of Sciences, control of the public higher education sector.Footnote 43 And while they have not managed to fully control Hungarian civil society, they have consistently manipulated the law in search of ways to diminish social accountability.Footnote 44

If the descent into populist authoritarianism was unexpected in Hungary it was even less expected in Poland, though it has not proceeded as far. First, the postcommunist side of the political divide collapsed earlier (in 2005) and was replaced by two party alternation by post-Solidarity political formations—Law and Justice (PiS) and Civic Platform (PO). PO was initially the more successful of the two formations, winning consecutive elections in 2007 and 2011. PiS took up a position as a mnemonic warrior arguing that the transition of 1989 had been stolen by a cabal of reform communists and opposition collaborators who had swindled the Polish nation. Initially, PO was able to effectively counter this strategy.Footnote 45 At least part of this was due to the unprecedented long-term growth of the Polish economy, which has been Europe's most consistent and fastest growing. It has grown every year from 1992 to the present without a downturn, though it did slowdown during the great recession. The GDP data are presented in figure 3 below.Footnote 46

Figure 3: Percent Change in GDP per Capita, Poland 1991–2017

Given this trend, it is hard to attribute the growth of populism in Poland to the kind of severe economic contraction and EU imposed austerity measures that plagued Greece, Spain, or Italy after the global fiscal meltdown. There is, however, a great deal of uncertainty and anxiety among the Poles about their economic future due to rapid economic and social change, particularly among workers in low-skilled sectors of the economy. Beyond the anxiety sparked by a global economic meltdown, there was a sense that growth is harder to maintain in today's global markets, that competition is intensifying, and that the global crisis itself made things more difficult in the long run.Footnote 47

There is evidence that the social change that accompanied rapid growth plays a role. A substantial part of Polish society is highly traditional and religious, and anxiety over social change can be as threatening as economic uncertainty, despite success.Footnote 48 The new prosperity in Poland has also been accompanied by higher levels of inequality, with gains more concentrated in high income groups, a trend that has been increasing since 2005.Footnote 49 Estimates put the percentage of materially deprived households in 2010 at 28.45, and severely materially deprived households at 14.2.Footnote 50 This too may well explain why the GDP figures presented above do not tell the whole story.

PO's popularity and credibility were hurt just before the presidential and parliamentary elections of 2015 when several of its leaders were illegally taped for dozens of hours. In June of 2014 the Polish news magazine Wprost released excerpts of these conversations.Footnote 51 The uncensored conversations did not cast either the party or some of its leading politicians in the best light and led to several prominent resignations, including that of the Speaker of the Sejm, Radosław Sikorski, and Jacek Rostowski, one of Prime Minister Ewa Kopacz's top economic advisors. It also led to a shake-up of the cabinet. The electoral season in Poland coincided with the refugee crisis in Europe. The presidential election was held in May at the beginning of the crisis and Parliamentary elections at its height in October. The Kopacz government found itself in the difficult position of supporting the humanitarian efforts of the EU to aid refugees and at the same time pushing back on higher quotas for Poland and rejecting the notion of accepting economic immigrants.Footnote 52 Just prior to the parliamentary elections, Kopacz agreed to admit an additional 5000 refugees, adding to the previously negotiated level of 2000, though she explicitly requested that they be Christians. PO's opponents on the right, as well as the newly elected PiS presidential candidate Andrzej Duda, were hostile to taking in refugees, and Kopacz's attempts to work with the EU did not help the party's electoral fortunes.Footnote 53 Poles tend to look at immigration as an emotional issue and are easily swayed by affective arguments against it.Footnote 54

During the period of PO rule there was substantial growth in rightwing mobilization in Polish civil society. As in Hungary, substantial organizing took place across the country in many local communities. In particular, the Clubs of Gazeta Polska, a conservative weekly, have been crucial in creating rightwing political networks in many localities and have been seen as instrumental in drumming up support for PiS throughout the country in the 2015 electoral campaign.Footnote 55 There has also been extensive growth in far-right and skinhead activity, aimed at stigmatizing ethnic and religious minorities, LGBTQ+ individuals and their organizations, and feminists, including a constant barrage of propaganda from the Radio Maryja, a traditionalist Catholic outlet.Footnote 56 One of the most curious aspects in this regard has been the creation of the reactionary counternarrative of the “ideology of gender” that is seen as the center of a challenge to traditional norms.Footnote 57

PiS and other forces on the right have used a number of public events to build their capacity for protest and create intense support. There is extensive belief in a conspiracy that members of the PO government conspired with the Russians to hide the truth about the Smolensk tragedy of 2010 in which President Lech Kaczyński and many other prominent Poles perished. The efforts of the PO government to move a memorial cross from in front of the Presidential Palace to the St. Anne Church across the street was the subject of extensive protests and counter-protests throughout the summer and fall of 2010.Footnote 58 Another important mobilizing event for the right is the annual Independence Day March in Warsaw on November 11. This National Holiday, marking the restoration of the country's sovereignty, had not been officially celebrated since the interwar era. The opposition had marked it in various unofficial ways starting in the 1970s, and it was officially restored in 1989 under PZPR rule. After 1989, it was officially celebrated in solemn ways, but did not initially include an official march. This changed in 2006 when the National Radical Camp (ONR) marched through Warsaw. In 2008 two far-right groups—the All-Polish Youth and the ONR—began to organize annual marches. The early marches were limited to this milieu and attracted only a few participants. Since 2010 it has grown in both size and controversy. Periodically, it has erupted in violence between far-right marchers and the police. Beginning in 2012, President Bronisław Komorowski attempted to organize an official state march in response to the desire of many mainstream Poles to celebrate the anniversary. The effort was not a full success as the far-right continued to march separately.Footnote 59 In 2018, the 100th anniversary of Polish Independence, President Duda also led an official march, and it reached its largest size (estimates run as high as 250,000). More recent marches have attracted a large number of ordinary Poles, but still attract a substantial concentration of far-right zealots whose provocations consistently grab headlines.Footnote 60 As in Hungary, the ability of the right and the far-right to protest, demonstrate, and mobilize has generally grown, abetting the rise of the populist right to power.

Public opinion polls showed PO losing its advantage over PiS in April 2015 just prior to the May Presidential election. Incumbent Bronisław Komorowski came in second in the first round to PiS challenger Andrzej Duda, and lost in the second round. In the October Parliamentary elections PiS won 38 percent of the vote and became the first party in postcommunist Poland to win a majority of seats in the Sejm (235/460) and the Senat (61/100).Footnote 61 In the period since the party has moved to undermine horizontal accountability mechanisms, in particular weakening the independence of the judiciary and the state media, turning them into the propaganda arm of the ruling party.Footnote 62 PiS has not been as successful as Fidesz. Its tenure in power has been shorter. The EU seems more proactive in calling out Poland and resistance by Polish civil society seems stronger. PiS also lacks the kind of constitutional majority that Fidesz has. In the elections of 2019, PiS held onto its majority in the Sejm, but lost its majority in the Senat. However, Senat rejection of bills passed by the Sejm can be overruled by an absolute majority of the latter; thus PiS retained the far more important of the two houses.

Whereas it is not unreasonable to talk about a Fidesz dictatorship in Hungary, it would certainly be premature to talk in such terms about Poland. Why has Fidesz been much more effective than PiS in realizing its populist vision? At first blush, the Fidesz government has had a substantially longer tenure in power and its electoral system more readily converts pluralities and majorities into constitutional majorities. Thus, Fidesz has faced less horizontal constraint on its rule to start compared to PiS, and it has used its ability to rewrite the constitution to further reduce it.

Further, popular pushback against PiS has been stronger in Poland. My intent here is not to dismiss the resistance in Hungary. There have been some large and truly impressive protest campaigns. Recently the protests against the attacks on CEU, or stripping overtime protection from workers and reducing autonomy in the higher education sector have been large, involving tens of thousands of participants, and have been sustained. Still, the volume and intensity has been greater in Poland. Thus PiS, while facing stronger horizontal constraints, also faces stronger social accountability. In contrast, in Hungary the lack of almost any horizontal constraint has allowed Fidesz to crack down on civil society and take control of the press, undermining social resistance to its exercise of power.

Early on, the lead in Poland was taken by the Committee in Defense of Democracy (KOD), which organized street protests in defense of the Constitutional Tribunal, the politicization of state media, and the civil service.Footnote 63 Polish women's and feminist movements also moved to block attempts to reduce reproductive freedom through a sustained campaign that culminated in the Black Monday (October 3) protests of 2016, when hundreds of thousands of Polish women dressed in black in protest against further restrictions to safe abortion access, including in cases of rape, incest, and threats to the mother's life and health.Footnote 64 Similarly, in July 2018, a proposal to reduce the retirement age of judges to appoint more PiS candidates onto the bench was met with extensive public protest in defense of the constitution.Footnote 65 And in January 2020, judges from several European countries marched in Warsaw in support of Polish judges and supporters of the rule of law. Following a ruling by the Constitutional Court, which was aimed at reducing access to safe abortions, a month of new women-led protests erupted in the fall of 2020, which were more extensive than the events of 2016.

The questions that motivated this study were how and why Poland and Hungary have become twin poster children for democratic backsliding. It treats their extrications from communism as critical junctures in which domestic actors freed of the constraints of the communist past launched fledgling democracies. We can think of Hungary's twenty years of democracy and Poland's currently threatened democracy as products of that juncture, which achieved a measure of path dependence. However, we know that institutional lock-in is subject to disruption by exogenous shocks and changing structural constraints, which is precisely what has happened in the last several years.

The pattern of extrication in both countries had long-term ramifications that were not anticipated by the literature on democratization. Transition theory posited a dichotomy between extrication processes from authoritarianism as either accommodative (negotiated, pacted) or contentious. This article argues that this dichotomy misses something fundamental about the Polish and Hungarian transitions, however. They were both accommodative and contentious. In both cases Roundtable Negotiations partially solved the procedures for democratizing the political system but left important issues unresolved. And these were resolved by pressure from below organized by political actors, by contentious politics.

This combination of contention and accommodation created a contentious discursive space for actors from the communist-era opposition following democratic transition. These memory warriors argued that the democratic transition was illegitimate because competing elements from the anti-communist opposition purportedly colluded with the communists in negotiation and continued to collaborate with postcommunist successor parties, thus protecting their power and privilege. This contentious and accommodative pattern of transition thus created a potential grievance that actors schooled in contentious politics could pursue. PiS and its predecessors attacked the Polish roundtable from the outset. It was not until 2015, however, that they were able to win an election that gave them a free hand to govern, despite participating in or leading earlier governments. Fidesz moved from youthful liberalism to the center-right and to outright illiberal extremism over time. 2006 represented a breakpoint in the degree to which it would utilize extremism to pursue its aims, and subsequent development provided a conducive environment for it.

The memory warrior strategy was less successful directly following democratization, but conditions began to change in 2004 with the admission of both countries into the EU. Paradoxically, members can flaunt EU norms with greater impunity than candidates for admission. Candidates are monitored more systematically and can have their membership postponed or rejected for bad behavior. Admission gave PiS, Fidesz, and other actors the leeway to resurrect cultural elements from past nationalist and xenophobic traditions, and to deploy anti-Brussels rhetoric to combat the EU's efforts to curtail the reemergence of these divisive discourses.

The global financial crisis and ensuing Great Recession had a powerful impact in Hungary, where the Gyurcsány government was already under attack for its misrepresentation of the economy during the elections of 2006. When the economy went into deep recession, the triumph of Fidesz in the election of 2010 was preordained. Poland's record setting economic growth only slowed during the recession, and dissatisfaction was more concerned with inequality and the erosion of traditional values that accompanied economic growth. Finally, the European refugee crisis of 2015 was the main precipitant of PiS's return to power that year. In the case of Hungary, it worked to extend Fidesz's grip on power when it looked like Jobbik might well overtake them. Orban's use of xenophobia, his declaration of illiberalism, and cultural attacks on the west allowed Fidesz to recover.

Ultimately, entry into the EU reduced constraints on the extremism of the arguments that PiS and Fidesz could deploy in politics. And the sequential economic and refugee crises constituted a major challenge for democracy both in Europe and globally that made the memory warrior assault on democracy more attractive to the voters. The illiberalism of the present is the product of a long-term legacy of the combination of accommodative and contentious extrication from communism. However, the danger posed by the memory warriors to democracy was realized only in the context of the economic and security crises of European liberalism in the 2000s. Furthermore, when the crisis of liberal-democracy emerged, both PiS and Fidesz were not only ideologically positioned to benefit but had invested in civil society organization as a long-term strategy to enhance their electoral effectiveness. At critical junctures, such as crises, the political forces that have the superior organization at the level of civil society have a distinct advantage.

If illiberalism has gone further in Hungary, it has been because the conditions there have been more fortuitous. Not only has Hungary been beset by both external shocks, but the timing of the second allowed Orbán to beat back Jobbik's challenge. Further, democratic institutions in Hungary, engineered to promote governability rather than representation by favoring larger parties to a greater degree than in Poland, made it much easier to enact antidemocratic constitutional change. While PiS has generally led a disciplined government, it has faced greater social constraints from organized protest. This combination of less conducive democratic institutions and greater counterpressure from below may serve to preserve minimal levels of democracy in Poland, whereas Hungarian democracy will need to be rebuilt in the future.