The importance of diversity is routinely proclaimed by leaders of the legal profession. Footnote 1 Socio-legal scholars, testing these proclamations against reality, have evaluated the diversity of large corporate law firms, law schools, and the judiciary. Footnote 2 However, similarly thorough study has not yet been made of diversity within the leadership of law societies and bar associations. Footnote 3 These organizations are of central importance in North America’s distinctive self-regulatory approach to legal services regulation. Footnote 4 In addition to long-standing authority over who can be a lawyer, and over what lawyers must and must not do, lawyers’ self-regulatory organizations increasingly bear responsibility for access to justice and for reconciling professionalism values with marketplace values. Footnote 5

When lawyers vote to elect the leaders of these self-regulatory organizations, what sort of people do they vote for? How representative of Ontario’s diversity are the Law Society benchers? How does the selection process affect the diversity of self-regulatory leaders and other elite lawyer sub-groups? To respond to these queries, this article quantitatively assesses the demographic and professional diversity of leadership in Ontario’s legal services self-regulator, the Law Society of Upper Canada (LSUC). Candidate campaign materials and voting pattern data from the five LSUC bencher elections since 1999 provide the data for the analysis. Footnote 6

The results suggest that those who currently lead the Law Society (known as benchers) are not disproportionately “male and pale.” Non-white members and women were elected in numbers proportionate to their shares of Ontario lawyers in the 2015 election. Regression analysis suggests that being non-white is not a disadvantage in these elections. Footnote 7 Being a woman actually seems to confer a surprisingly significant advantage. Footnote 8 This contrasts with the diversity situation in other elite subgroups of Canadian lawyers, especially the judiciary. The diverse employment contexts of the province’s lawyers were also fairly well represented in the 2015 class of benchers. Footnote 9 However one constituency—early-career lawyers—was completely unrepresented in the Law Society’s elected leadership. Footnote 10

This article begins by reviewing the literature on diversity, or lack thereof, in the legal profession and its regulatory leadership (Part I). The LSUC and its election system are introduced in Part II. The data source, hypotheses, and methodology for this study are discussed in Part III. The central empirical findings of this research, presented in Part IV, assess the diversity of the Law Society’s elected leadership along dimensions of diversity: visible minority/aboriginal status, practice context, gender, and career stage. Turning to the broader significance of these findings, Part V considers the effect of selection processes on the diversity of different elite legal subgroup groups. Part V also argues for career-stage constituencies in LSUC bencher elections, in order to position self-regulatory governance to better serve the public interest. Part VI summarizes and concludes.

1 Diversity in the Legal Profession and Its Leadership

Legal professionals in developed countries are usually less demographically diverse than the general populations from which they are drawn. For example, women and non-white people are generally under-represented among lawyers both in the United States Footnote 11 and in Canada. Footnote 12 Those who do become lawyers also often earn less money than their white male colleagues. According to Ronit Dinovitzer’s Law and Beyond survey, troubling income divergences are already apparent just two years after Canadian lawyers are licensed. Footnote 13 Black lawyers had a median income of $65,000, compared with $78,200 for other lawyer respondents. Footnote 14 Female lawyers earned on average only 93 percent of men’s salaries, just two years out. Footnote 15

Diversity in legal positions that are better paid or considered elite often trails behind diversity in the profession at large. Women and non-white people seem to be “funnelled out” after becoming lawyers: they are less likely to be found in roles such as judge and large firm partner than they are among “rank and file” lawyers. This is apparently true in several world jurisdictions, Footnote 16 including Canada. Of 2,160 Canadian judges analyzed in a recent study, only one percent were aboriginal and three percent were members of visible minorities. Footnote 17 Women are also still significantly underrepresented in the judiciary, even relative to their share of the legal profession. Footnote 18 Canada’s large “Bay Street” corporate law firms are suspected in some quarters of a similar reluctance to diversify their top ranks, Footnote 19 although reliable quantitative data are not yet available on this point. Footnote 20

Nevertheless, progress towards legal profession diversity has been made in parts of the world, especially at the entry level. In most developed countries, the newest cohorts of lawyers include approximately equal numbers of men and women. Footnote 21 Proportionate representation has also been achieved by black and minority ethnic (BME) individuals among the solicitors and barristers of England and Wales Footnote 22 and by Asian-born individuals among Australia’s solicitors. Footnote 23

Quantitative data can help us understand the profession’s diversity challenges, successes and opportunities. Footnote 24 This article therefore offers a quantitative diversity analysis of one elite lawyer sub-group: leaders of the Law Society of Upper Canada. The LSUC is the self-regulatory organization governing Ontario legal professionals.

Demographic dimensions of diversity such as gender, visible minority status, and aboriginal status are important in this context. As Faisal Bhabha notes, all of Canada’s law societies including the LSUC have made institutional commitments to diversity along such demographic dimensions. Footnote 25 However, professional dimensions of diversity, such as firm size and geographical location, are also relevant. Are sole practitioners, lawyers in firms of different sizes, and in-house corporate and government lawyers found in numbers proportionate to their numbers in the profession? How well are lawyers at different stages of their careers represented?

Demographic and professional diversity in regulatory leadership is a matter of equity, but also arguably a matter of professional vitality. Commentators have suggested that the robust form of self-regulation enjoyed by American and Canadian lawyers is at risk of being replaced by state-dominated “co-regulation,” as it already has in the United Kingdom and Australia. Footnote 26 Drawing on perspectives from a diverse group of leaders may strengthen lawyers’ self-regulatory organizations. It can help them make better-informed decisions in the public interest, on specific discipline files but also on broader policy issues such as legal education, articling and licensing reform, and whether to permit non-lawyer investment in law firms.

Some legal self-regulatory organizations are diverse by constitutional design. The American Bar Association House of Delegates, for example, includes representatives of the Young Lawyers Division, the National Association of Women Lawyers and the Solo, Small Firm, and General Practice Division among others. Footnote 27 The Council of the Law Society of England and Wales includes seats representing groups such as the Black Solicitors’ Network, the Child Care Law group, and the Junior Lawyers Division. Footnote 28 By contrast the Law Society of Upper Canada, which is the focus of this article, ensures geographically diverse representation but leaves other dimensions of diversity to the candidates and the voters.

2 The Law Society of Upper Canada

Ontario’s 51,000 licensed legal professionals are regulated by the LSUC. Footnote 29 Compared with lawyers’ self-regulatory organizations in other countries, the Law Society enjoys a hegemonic position in Ontario legal services regulation. Footnote 30 It establishes entry, conduct, and business structure rules for legal professionals, and it exercises professional discipline, with minimal interference from either the government or the courts. Footnote 31 Law Society membership is mandatory for all Ontario lawyers and licensed paralegals. Footnote 32

The Law Society is led by “benchers,” who assemble formally in “Convocation.” Footnote 33 Benchers serve part-time, in a role somewhat comparable to corporate directorship. Footnote 34 Apart from the Attorney General (a provincial cabinet minister) and eight non-lawyers appointed by the government, the voting benchers are elected by licensed legal professionals. Five benchers are licensed paralegals, and forty are licensed lawyers. In addition to making major policy decisions and serving on disciplinary hearing panels, the benchers elect a Treasurer to serve as their President, and appoint a permanent Chief Executive Officer of the Law Society. Footnote 35

2.1 Law Society Bencher Elections

The focus of this paper is the forty elected lawyer benchers, who make up approximately 75 percent of those eligible to vote on most Law Society decisions. Footnote 36 Elections for lawyer benchers are held every four years, most recently in April of 2015. Any lawyer whose license has not been suspended may be a candidate, provided that he or she is nominated by five other lawyers. Footnote 37 There is a term limit for elected lawyer benchers of twelve years (three terms). Footnote 38

In the terminology of electoral design, lawyer benchers are elected under a multi-member, two-district plurality voting system. The electoral constituencies are based on geography. Each Ontario lawyer may vote for up to twenty candidates practicing law within the City of Toronto, and for up to twenty candidates practicing law elsewhere in the province. Footnote 39 One distinctive feature of this electoral system is that while there are two districts (Toronto and non-Toronto), Footnote 40 each voting lawyer can vote for up to twenty candidates from each district, regardless of where the voter resides. This ensures that non-Toronto candidates make up half of Convocation, which would otherwise be unlikely. Footnote 41

In a further effort to ensure that all regions are heard from, a regional bencher provision was adopted in 1999. This system divides the province into eight regions, and designates the candidate practicing within each region who receives the most votes from the voters in that region as “Regional Bencher.” Footnote 42 The regional bencher provision does not add to the count of forty elected lawyer benchers, but it does ensure that Convocation will include lawyers from across the province.

However, the regional districts and constituencies also mean that non-Toronto candidates with relatively few votes are elected in lieu of Toronto candidates with significantly more votes. For example, in the 2015 bencher election, Fred Bickford was elected Regional Bencher for the sparsely-populated Northwest region of Ontario. Footnote 43 Mr. Bickford received 101 votes from lawyers in that region, along with 778 votes from lawyers in the rest of the province for a total of 879 votes. Footnote 44 By contrast, Toronto candidates Tanya Walker and Renatta Austin received 2,871 and 2,329 votes respectively but were not elected because they stood twenty-second and twenty-seventh within the Toronto district. Footnote 45

Walker and Austin are both women in their first decades of practice, and they are both members of visible minorities. Their candidacies exemplify the apparently deleterious—although presumably unintended—effect that the regional constituency system has on other dimensions of diversity. This topic is further considered in Parts V and VI of the paper.

3 Methodology

3.1 Data Source

This analysis draws on data about 486 bencher candidacies from the five Law Society elections held since 1999. These data were obtained from the Law Society’s election records and from bencher election candidate guides. Footnote 46 The guides contain a one-page statement and a picture from each candidate in each election. A candidate’s statement typically includes biographical information, policy proposals, and occasionally endorsements from individuals or organizations.

For each candidacy, the outcome measures were (i) whether or not the candidate was elected, and (ii) the candidate’s vote share, expressed as a percentage. If a candidate had a 20 percent vote share in the 2015 election, that means her name was selected by 20 percent of all lawyers voting in that election. Footnote 47 The average vote share among all 486 candidacies was 15.1 percent, and the average elected candidate had a vote share of 22.7 percent. Because of the regional constituency system described above, the elected candidates were not always those with the highest vote shares. Footnote 48

The key independent variables were the various “dimensions of diversity” applicable to the candidates. These were (i) Region; (ii) Visible Minority / Aboriginal Status; (iii) Practice Context (firm size or employment status); (iv) Gender; and (v) Career Stage (for 2015 candidates only). A sixth independent variable, Name Recognition Proxy Measure, was added to help isolate the effects of the others. Footnote 49 The research team gathered this information about each candidate from the candidate statements (supplemented, where necessary, by internet searches). Data were stored and analyzed in a FileMaker Pro database, in Excel spreadsheets, and in the SPSS statistical analysis package.

3.2 Hypotheses

The author formulated the five top-level hypotheses with regard to these data.

-

Hypothesis 1. Non-white people are funnelled out:

-

1a. in the process of becoming lawyers (they are less likely than white people are to be lawyers);

-

1b. in the bencher nomination process (they are less likely than white people are to be bencher candidates);

-

1c. in the bencher elections (they attract fewer votes than white candidates do).

-

-

Hypothesis 2. For those in private practice, the size of the firm in which a candidate practices is positively correlated with the candidate’s vote share (candidates from larger firms get more votes).

-

Hypothesis 3. Women are funnelled out:

-

3a. in the process of becoming lawyers (they are less likely than men are to be lawyers);

-

3b. in the bencher nomination process (they are less likely than men are to be candidates for bencher);

-

3c. in the bencher elections (they attract fewer votes than male candidates do).

-

-

Hypothesis 4. Early-career lawyers are funnelled out:

-

4a. in the bencher nomination process (they are less likely than later-career lawyers are to be bencher candidates);

-

4b. in the bencher elections (they attract fewer votes than later-career candidates do).

-

-

Hypothesis 5. The status quo geographic constituency voting system reduces the demographic diversity of the elected benchers, compared with a hypothetical system in which the top vote-getters are elected regardless of where they practice.

3.3 Analysis of Data

Representativeness along the dimensions of diversity was analyzed by comparing each class of elected benchers with: (i) all candidates in that election, (ii) the population of Ontario lawyers at the time of the election, and (iii) the entire population of Ontario at the time of the election (where applicable). The effects of candidate characteristics on voter behaviour were estimated using ordinary linear regression, with candidate vote share as the dependent variable. This method estimates the effect of different candidate diversity attributes (e.g. being non-white or being a woman) on voters’ willingness to support that candidate. Footnote 50

Omitted variable bias and selection effects are possible problems with this method for estimating effects on voter behaviour. Footnote 51 It could be that an unmeasured variable exerts an influence on voter behaviour and renders one or more of the apparent effects spurious. For example, female candidate gender appears to have a significant positive effect on voter support. Footnote 52 The Name Recognition Proxy Measure data, described in the Appendix, was collected to test whether this was actually a consequence of differing levels of name recognition among male and female candidates. Footnote 53 The regression analysis suggests that this is not the case. Footnote 54 However, it remains possible that controlling for some other unknown variable would diminish or eliminate the effects reported here.

It is also important to note that the candidates were self-selected, not randomly selected, from the population of Ontario lawyers. This makes it conceivable that the candidates differ from the lawyer population in a manner that skews this study’s results. Nevertheless, the results presented here illuminate voters’ preferences in choosing among actual candidates, and there is no reason in particular to believe that the candidate sample is skewed in a meaningful way.

The regression results for all candidates in the five elections are presented in Table 1. Results that are statistically significant at the 0.05 level are in boldface. Part IV (below) will discuss the statistically significant findings from this regression analysis.

Table 1 Regression Analysis: All Candidates

a This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant.

A separate regression analysis was performed of 2015 candidates (Table 2). For this group, two additional types of data were available: Name Recognition Proxy Measure and practice context. Footnote 55

Table 2 Regression Analysis: 2015 Candidates

a This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant.

4 Diversity in Regulatory Leadership and Voter Preferences

4.1 Non-White Status

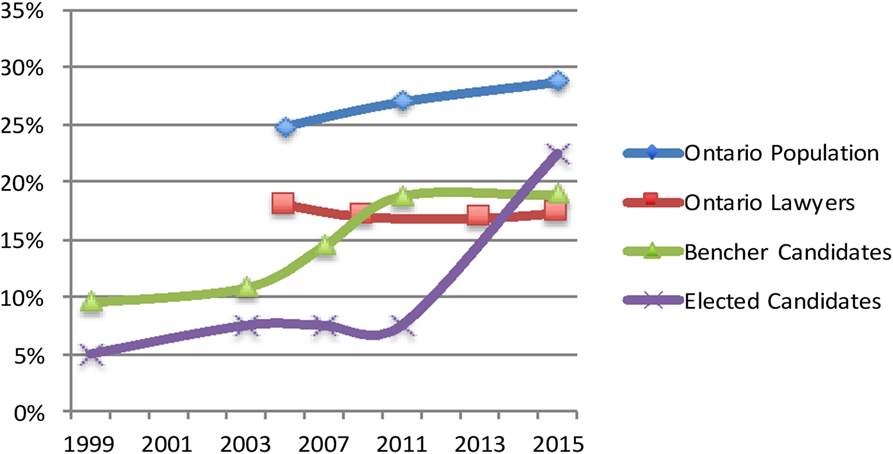

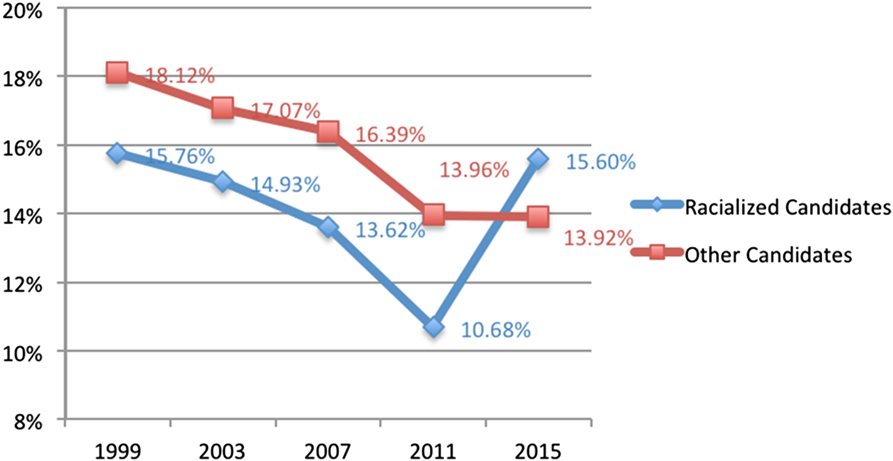

The 2015 election was either a historical anomaly, or a breakthrough for non-white candidates. The nine candidates who were elected constitute 22.5 percent of the total, which exceeds their share among Ontario lawyers (Table 3 and Figure 1). This figure remains below the 26.2 percent share that visible minorities and aboriginals together hold within Ontario’s population according to the 2011 census.

Table 3 Proportion Who Are Non-White

Figure 1 Proportion who are racial minority members.

The average vote share received by non-white candidates in 2015 exceeded the average share received by white candidates, while in previous elections the opposite was true. However, the regression analysis shows no statistically significant correlation between non-white status and vote share, either in 2015 or over all five elections (Figure 2). Footnote 56 Thus, regarding the funnelling out of non-white individuals, hypothesis 1(a) cannot be rejected but hypotheses 1(b) and 1(c) can be rejected based on these data. Footnote 57

Figure 2 Average vote share by candidate status, 1999–2015.

4.2 Practice Context

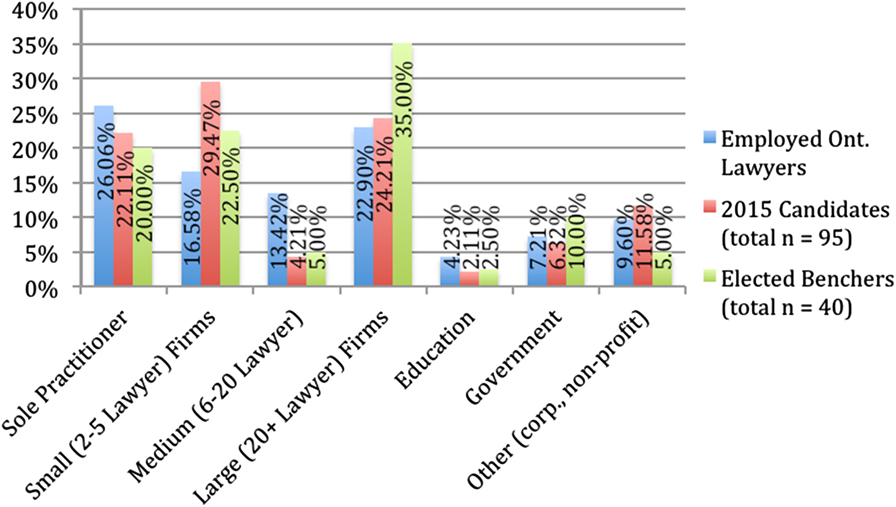

Practice context is a “professional” dimension of diversity that many people want to see reflected in lawyers’ self-regulatory leadership. Concerns have been raised about whether sole practitioners, corporate in-house counsel, and lawyers with non-litigation practices are appropriately included in Ontario’s benchers. Footnote 58 From this point of view, it is encouraging that the benchers elected in 2015 include some lawyers with each of the major employment statuses found in the Ontario bar (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Proportion by employment context in 2014–2015.

That being said, the benchers are not perfectly representative along this dimension of diversity. No in-house corporate lawyers were elected. Lawyers practicing in firms larger than twenty are over-represented, with 22.9 percent of the province’s lawyers but 35 percent of the benchers (n = 14). According to the analysis in Table 2, practicing in a large firm (twenty or more lawyers) has a significant positive effect on vote share received. Meanwhile the medium-size firms (six to twenty lawyers) would require an additional three to four benchers to be proportionately represented, and sole practitioners would require an additional two to three benchers. However, there is no significant correlation between these other practice contexts and vote share. The data partially support hypothesis 2 regarding the correlation between firm size and vote share. Footnote 59

4.3 Gender

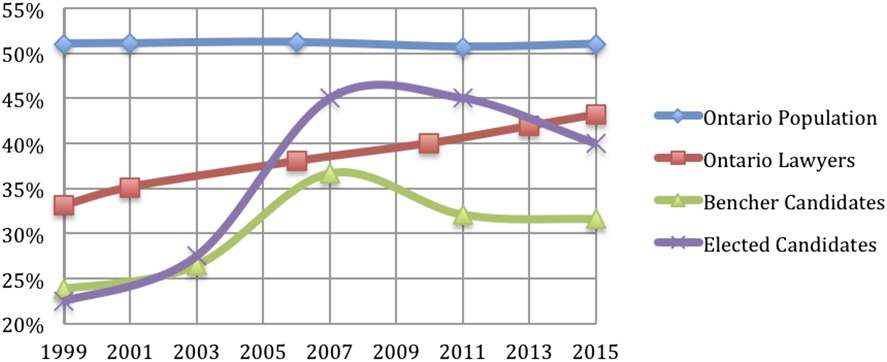

In the 2007, 2011, and 2015 elections, women were elected as benchers in numbers proportionate to their share of the Ontario legal profession. Table 4 shows the evolving gender balance over time. Of the 120 benchers elected over this period, 43.3 percent (n = 52) have been women. In 2013, women made up 41.9 percent of all Ontario lawyers (Figure 4), confirming hypothesis 3(a). Footnote 60

Table 4 Proportion who are Female

Figure 4 Proportion who are female.

Consonant with hypothesis 3(b), women are less likely than men to be candidates, in these as in some other elections. Footnote 68 However, exactly 50 percent of the 144 female candidates in bencher elections since 1999 were elected, compared with only 37.2 percent of the 341 male candidates. Female candidates have tended to attract more votes: an average vote share of 17.7 percent, compared with 14.7 percent for the average male candidate. Footnote 69 The linear regression analyses show that gender has a significant effect after controlling for the other measured variables such as candidate name recognition and years of experience. They also show that the gender effect was larger in 2015 than it was in previous elections. Footnote 70 Thus, hypothesis 3(c) (voter preference for male candidates) can clearly be rejected based on these data. Footnote 71

4.4 Career Stage

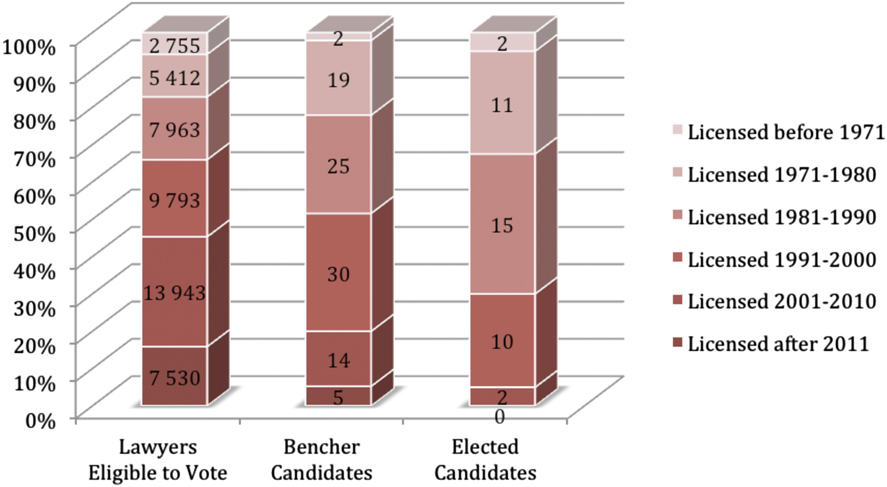

Early-career lawyers make up the only group studied here that was significantly under-represented in the 2015 class of benchers. Those who had been practicing for less than fifteen years, who made up almost half of all Ontario lawyers at the time (45.31% of the total, n = 21,473), contributed only two of the forty benchers elected in 2015 (Figure 5). These two benchers had twelve and thirteen years of experience respectively. None of the benchers elected in 2015 were among Ontario’s lawyers in the first decade of practice, who made up 25 to 30 percent of all lawyers in the province.

Figure 5 2014–2015 lawyers, candidates, and elected benchers by career stage.

The under-representation of recent licensees is not a new phenomenon. Of the 200 benchers elected in the five general bencher elections since 1999, only six were licensed less than ten years before they were elected. Moreover, two of these six had lengthy careers in other fields before being licensed as Ontario lawyers. The average bencher elected over this period had been licensed in Ontario for 27.53 years at the time of his or her election. Footnote 72

4.4.1 Why are recent licensees under-represented?

On one level, the lack of early-career benchers is not surprising. Career stage is obviously correlated to age, and older individuals predominate in most elections. Footnote 73 The average age of benchers is similar to the average age of Canadian members of parliament. Footnote 74 Nevertheless, it is worth asking why there are not more early-career benchers, and the data offer some insights on this point.

The candidate pool is one factor. Since 1999, only 10 percent of the bencher candidates (an average of 9.8 candidates per election) have been in the first decades of their careers. In fact, the average career stage of candidates has increased steadily over this time, from 21.06 years post-license in 1999 to 24.53 years post-license in 2015. Thus, hypothesis 4(a) regarding funnelling out of early-career lawyers at the nomination stage is supported.

Voting patterns are also relevant. First-decade lawyers had an average vote share of 10.75 percent, compared with 16.04 percent for later-career candidates. Mean vote share per candidate climbs along with experience category, and the regression analysis for all five elections (Table 1 above) shows that those in the first two experience categories (zero to ten years and ten to nineteen years) received significantly fewer votes than their more experienced colleagues did. Footnote 75 Voters in Law Society elections may perceive later-career candidates to have advantages such as life experience, career security, and the discretion to dedicate more time to the work of serving in Convocation.

However, in the 2015 candidate regression analysis, where name recognition data are included, the career-stage effect is no longer statistically significant. Footnote 76 Thus, it is plausible that candidate experience has a less important effect on voter behaviour than does name recognition. If so, it is not necessarily (or not entirely) that voters prefer older candidates per se, but rather that they tend to vote for candidates whom they have heard of. Given that there is very little campaigning, name recognition will primarily be developed over time, and early-career candidates are less likely to enjoy this advantage. Thus the data only partially support hypothesis 4(b) regarding funnelling out of early-career lawyers at the vote-getting stage.

The candidate pool and voter behaviour cannot entirely explain the lack of early-career lawyers in Convocation. First-decade lawyers received 6.86 percent of all the votes cast in the five elections since 1999, but made up only 3 percent of the benchers elected. The constituency system, which is explored in the next section of this paper, is a significant cause of the dearth of early-career lawyers in the Law Society’s leadership.

5 Elite Sub-Groups, Selection Processes, and Diversity

In order to place the data in a broader context, this part asks what the findings can tell us about the relationship between selection processes and diversity. The consequences of the law society constituency system for bencher diversity are considered first. An argument for career-stage constituencies in legal self-regulator elections is then made in section 2 of part V. Finally, section 3 asks whether the relatively strong diversity of the 2015 benchers indicates a path toward greater diversity in other elite lawyer sub-groups such as judges.

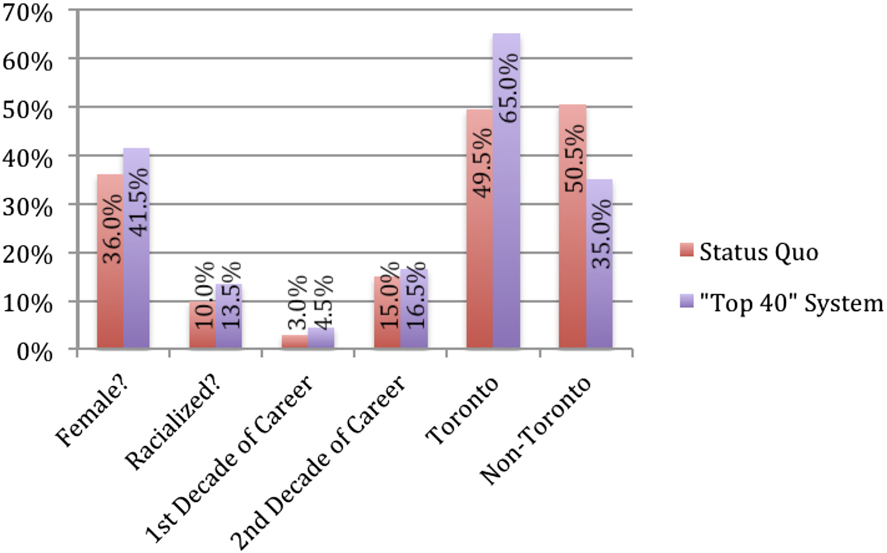

5.1 Law Society Bencher Election Constituencies

As noted above, the current Law Society constituency system is based entirely on geography. It favours non-Toronto candidates, who need many fewer votes than their Toronto colleagues do to be elected. Footnote 77 It is possible, however, to imagine alternatives that would have interesting effects on diversity. What if there were no geographic constituencies, and the top forty vote-getters in each election became benchers? As Figure 6 shows, under this “Top 40” system the leadership since 1999 would have included more women, more visible minority lawyers, and more early-career lawyers. The number of non-white benchers elected would have increased most dramatically, from twenty to twenty-seven (Table 5). Thus, hypothesis 5, regarding the effect of the status quo system on diversity, is clearly supported. Footnote 78

Figure 6 Benchers elected in past five elections under different constituency systems.

Table 5 Numbers of Benchers elected under status quo and “Top 40” systems

The Top 40 system would have elected a more demographically diverse Convocation because female, non-white, and early-career candidates are more likely to run in Toronto than outside of the city. Footnote 79 Tanya Walker and Renatta Austin, who ran in 2015 and would have been elected under Top 40, are examples. Footnote 80 This system would also, arguably, better reflect the collective democratic will of Ontario’s lawyers, insofar as candidates like Walker and Austin would be chosen instead of candidates who garnered less than half as many votes as they did.

Unfortunately, these benefits would come at the expense of geographic diversity. Over the five elections, Top 40 would have produced 130 out of 200 elected benchers practicing in Toronto, leaving non-Toronto lawyers under-represented relative to their numbers in the profession. Also, it is worth recalling that the status quo system did elect proportionate numbers of women and non-white lawyers in the 2015 election. Footnote 81 Indeed, among the dimensions of diversity analyzed here, career stage is the only one for which the most recent class of benchers is significantly unrepresentative of Ontario’s practicing bar.

5.2 For Career-Stage Constituencies

Introducing career-stage constituencies, as candidate Renatta Austin proposed, Footnote 82 would fix this problem without undermining geographic diversity. The By-Laws could be amended to provide that each five-year career stage (lawyers with zero to five years of practice; lawyers with five to nine years of practice; etc.) must be represented by at least two benchers, one from Toronto and one from elsewhere in Ontario. Like the Regional benchers, the “Career-Stage Benchers” would be the candidates in each constituency who received the most votes from within those constituencies.

Why should regulatory leadership include career-stage diversity? Legal services regulation should serve the public interest, Footnote 83 and it should be client-centric as opposed to lawyer-centric. Footnote 84 A regulator with career-stage diversity in its leadership can better meet these challenges. Early-career lawyers have first-hand insight into important regulatory policy issues such as legal education (including the effects of tuition and debt) and the licensing process. They are the only lawyers likely to be working as employed associates in private practice. They can therefore speak knowledgeably in leadership meetings about key issues like the ethical pressures of billable hour requirements and reconciling partners’ demands with clients’ interests. In the words of early-career candidate Renatta Austin:

Adapting the regulatory model to the needs of the 21st century public, ensuring fair and equal access to the legal profession and cultivating a legal culture where diversity and inclusion are the norm, rather than challenges to be overcome, are policy issues that primarily impact the next generation of lawyers. Yet, we are largely excluded from the governance table. Footnote 85

That early-career lawyers have valuable perspectives on regulatory issues is recognized by some within the Law Society. Twenty of the 2015 candidate statements made reference to special issues facing these lawyers, Footnote 86 and Treasurer Janet Minor created a New Licensee Roundtable to hear from them. Footnote 87 While this attentiveness is commendable, it would be even better to have the voices of early-career lawyers heard in a democratic way within the leadership boardroom.

Guaranteeing early-career lawyers a voice within self-regulatory governance would also plausibly increase their participation in these elections. Turnout in Law Society bencher elections has declined steadily from 56.0 percent in 1987 to only 33.84 percent in 2015. Footnote 88 In the 2015 election, only 31.02 percent of those licensed between 2001 and 2010 participated. Footnote 89 Having the right to select one of their own to present their distinct perspective in Convocation could be a way to spark interest among relatively new lawyers.

It merits reiteration that failure to attract votes is not the only reason, or even the primary reason, why there are no early-career lawyers in Convocation. As noted above, under the pure democratic “Top 40” system, two lawyers in their first decades of practice would have been elected in 2015, including Renatta Austin who was licensed in 2013.

If early-career lawyers are to have their own constituencies, then why shouldn’t other groups such as in-house corporate counsel, non-litigating solicitors, or sole practitioners? Footnote 90 In the words of bencher Raj Anand, “Once you start creating seats, it’s difficult to know where to stop.” Footnote 91 Would the present proposal slide the electoral system down a slippery slope towards an elaborate tokenism with numerous niche constituencies? The result might have little correspondence to the democratic will of the electorate as indicated by the top vote-getters.

The law society embarked down the road of compromising pure “at large” democracy in favour of broad representativeness when it created geographic constituencies. Perhaps the question should actually be, why stop travelling now? Constituencies promote diversity and good decision-making, albeit at the expense of deviation from the collective democratic will of the electorate. Footnote 92 Travelling further down this road, representation could be based at least in part on communities of practice, defined by Lynn Mather et al. as “groups of lawyers with whom practitioners interact and to whom they compare themselves and look for common expectations and standards.” Footnote 93 As noted above, groups such as the American Bar Association and the Law Society of England and Wales have a somewhat comparable system. Footnote 94

Where exactly to stop on the road from pure democratic representation towards multiple constituencies is a question beyond the scope of this paper. The argument here is that, given the significant aspects of the public interest that early-career benchers could elucidate in Convocation, we should take at least this one further step down the road.

5.3 Diversity of Benchers and other Legal Elites

The process by which elite lawyer subgroups are selected seems to have consequences for the diversity of the groups. Notwithstanding the lack of early-career lawyers, the benchers elected in 2015 are significantly more diverse than other elite Canadian lawyer sub-groups. They are clearly more demographically diverse than the judiciary. Footnote 95 They are also likely more diverse than large firm partners (although the data are less clear on that point).

Why are Ontario’s benchers more demographically diverse than other elite sub-groups? Can any lessons be drawn for those who would like to see more diversity on the bench and in large firm partners’ suites? Benchers are chosen in a transparent election, in which any Ontario lawyer in good standing can run and each Ontario lawyer has an equal number of votes. Judges and large firm partners, by contrast, are invited into their respective clubs after opaque, closed-door processes controlled by existing club members and other elite actors. Expanding the base of decision-makers, and increasing the transparency of the decision-making process, might bring more diverse talent into these other elite lawyer clubs. Transparency is favourable to diversity, as Lyon and Sossin among others have pointed out. Footnote 96 The “diversity gap”—between our benchers selected through transparent elections on one hand, and our judges selected through mysterious backroom consultations on the other—arguably illustrates the relationship between transparency and diversity.

6 Conclusion

The diversity of lawyers in positions of self-regulatory leadership is important for at least two reasons. First, these are “elite” positions within the profession that carry power and prestige (as well as time commitments and service obligations). It would be highly problematic in equity terms if male, and/or “pale,” and/or “stale” lawyers had preferential access to them. Second, it stands to reason that self-regulatory governance will work best when it can draw on the talents and perspectives of as many parts of the profession as possible.

Self-regulatory organizations and their governance matter. Admittedly, some still follow Max Weber and write self-regulatory organizations off as mere stalking horses for privileged occupational groups dedicated to “closure of social and economic opportunities to outsiders.” Footnote 97 However, a more optimistic school envisions self-regulatory organizations creating opportunity, equity, and stability: not only for their diverse workers, but also for their diverse clientele and for society as a whole. Footnote 98 Across the common law world, legal self-regulatory organizations today take influential if not determinative positions on questions of legal education, access to the profession, and access to justice. The Law Society of Upper Canada, for example, is confronted with controversies about mandatory apprenticeship, Footnote 99 paralegal scope of practice, Footnote 100 and alternative business structures for law firms. Footnote 101 From this point of view, it is clear that the diversity and quality of law society and bar association leadership is relevant not only to practitioners of law but also to all those for whom law is practiced.

It is therefore encouraging to find that the lawyer benchers of the Law Society of Upper Canada elected in 2015 are broadly representative of Ontario’s legal profession in terms of gender, non-white status, and practice context. They are somewhat more “male” and “pale” than the general population, but no more so than the average Ontario lawyer. Only time will tell whether non-white candidates’ strong performance in 2015 was a blip or a breakthrough, but being a woman has consistently conferred a significant apparent advantage to candidates in attracting votes. Other important dimensions of diversity, such as sexuality and socio-economic status, cannot be evaluated on the basis of these data.

Despite the apparent diversity success in terms of gender and race, the lack of early-career lawyers was a gaping hole in the 2015 Convocation. While not necessarily “stale,” the average bencher was certainly in the middle or late stage of his or her career. Just as the lawyers of each region have the right to elect candidates from among themselves, lawyers in each five-year career-stage segment should be given the right to select two representatives to Convocation. This modest reform is arguably the last missing piece of the diversity puzzle at the Law Society. Introducing it now will help ensure that the Law Society can continue to confront its many challenges and opportunities as a robust and vital public interest regulator.

Appendix: Independent Variables for Statistical Analysis

The independent variables in this analysis are as follows:

-

(i) Candidate Region. As noted above, the province is divided into eight regions. Toronto is one of these, and twenty of the forty benchers are elected from Toronto.

-

(ii) Candidate Visible Minority or Aboriginal (yes/no). The team read each candidate statement. Based on the candidate’s name, picture, and statement, each team member indicated whether or not the candidate was, in the team member’s opinion, either (i) a member of a visible minority as defined by Statistics Canada, Footnote 102 or (ii) a member of an aboriginal group. Candidates meeting either one of these criteria, according to a majority of the three raters, were coded as non-white. Footnote 103

-

(iii) Candidate’s Practice Context. The following practice categories, used by the Law Society in its statistical reporting, were also used in this study: (1) Sole Practitioner; (2) Small Firm (2 to 5 Lawyers); (3) Medium Firm (6 to 20 Lawyers); (4) Large Firm (20+ Lawyers); (4) Employed in Education; (5) Employed in Government; and (6) Employed in Other Context (including corporate and non-profit sectors).

-

(iv) Candidate Female (yes/no). This was also coded by team members based on reading the statements and looking at the accompanying pictures.

-

(v) Career Stage (2015 candidates only). The year in which the candidate was first licensed to practice law in Ontario was subtracted from the year of the election to give the candidate’s years of experience at the time of the election. Footnote 104 Years of experience were aggregated into career-stage categories: (1) 0 to 9 years; (2) 10 to 19 years; (3) 20 to 29 years; (4) 30+ years.

-

(vi) Name recognition proxy measure (NRPM) (2015 candidates only). This measure included (i) the number of times the candidate had been mentioned in the two trade newspapers for Ontario lawyers, and (ii) the number of times the candidate’s name appeared in AccessCLE, which is the Law Society’s database of continuing legal education articles and presentations. Footnote 105 For each of the 2015 candidates, the number of hits from these sources prior to election day in 2015 was tallied. The reasoning behind this proxy measure is that the more often a candidate’s name appeared in an Ontario legal trade newspaper, and the more often he or she spoke at events for Ontario lawyers, the more likely it is that his or her name would have been recognized by voters reviewing the bencher election ballots. NRPM is not a dimension of diversity. However, as explained above, Footnote 106 it is correlated with vote share and its use strengthens the study’s conclusion about the effects of gender.