Introduction

On July 13, 2023, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) delivered its judgment in the case concerning Question of the Delimitation of the Continental Shelf Between Nicaragua and Colombia Beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Nicaraguan Coast (Nicaragua v. Colombia) (2023 Judgment).Footnote 1 This is the first decision addressing the question of the delimitation of the continental shelf, between states with opposite coasts, in a situation where one state asserts a continental shelf extending beyond 200 nautical miles (extended continental shelf) within the 200 miles from the baselines of another state.Footnote 2

Background

In Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia), Nicaragua had already requested the ICJ to delimit the overlapping area resulting from Nicaragua's entitlement, under Article 76(1) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to an extended continental shelf from its coast and the continental shelf within 200 nautical miles of Colombia's mainland coast.Footnote 3 However, in its 2012 judgment, the ICJ decided not to entertain Nicaragua's request since Nicaragua had not submitted information on the limits of its extended continental shelf to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) in accordance with Article 76(8) of UNCLOS.Footnote 4 Thus, Nicaragua had not established that it had a continental margin extending far enough to overlap with Colombia's 200 nautical mile entitlement to a continental shelf measured from Colombia's mainland coast.Footnote 5

On June 24, 2013, Nicaragua made a full submission to the CLCS, in accordance with Article 76(8) of UNCLOS, providing information on the limits of its extended continental shelf from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.Footnote 6 On September 16, 2013, Nicaragua instituted new proceedings against Colombia, requesting the ICJ to delimit the maritime boundary between Nicaragua and Colombia in the areas of the continental shelf that appertain to each of them beyond the boundaries determined by the ICJ in its 2012 judgement.Footnote 7

The ICJ's (Brief) Decision

The ICJ focused its decision on the question of whether, under customary international law,Footnote 8 a state's entitlement to an extended continental shelf may extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another state.Footnote 9 To reply to this question, the ICJ examined: (1) the relationship between the legal regime governing the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and that of the continental shelf extending within 200 nautical miles; (2) the legal regime of the extended continental shelf; and (3) the practice of states before the CLCS.

On the first point, the ICJ noted that the legal regimes governing the EEZ and the continental shelf within 200 nautical miles are different and distinct, but also interrelated.Footnote 10 The ICJ recalled that, under Article 56(3) of UNCLOS, which reflects customary international law,Footnote 11 within the EEZ the rights with respect to the seabed and subsoil are to be exercised in accordance with the legal regime governing the continental shelf.Footnote 12 In this sense, while a continental shelf can exist where there is no EEZ, there cannot be an EEZ without a corresponding continental shelf.Footnote 13 On the existence of “grey areas”Footnote 14 in the two “Bay of Bengal cases,”Footnote 15 the ICJ noted that “grey areas” of limited size were created as an “incidental result” of the use of an adjusted equidistance line in a delimitation between adjacent states.Footnote 16 Since the circumstances of those cases were different from the case at hand, the ICJ did not consider them relevant to answering the first question.Footnote 17

On the second point, the ICJ recognized that, under customary international law, there is a “single continental shelf,” to the extent that rights of the coastal state over its continental shelf are generally the same within and beyond 200 nautical miles from its baselines. However, it also noted that, under customary international law as reflected in Article 76(1) of UNCLOS, a state's entitlement to a continental shelf had two different bases: the distance criterion (continental shelf up to 200 nautical miles from the coast) and the natural prolongation criterion (beyond 200 nautical miles, with the outer limits to be established on the basis of scientific and technical criteria).Footnote 18

The ICJ then examined the travaux préparatoires of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) and concluded that the possibility of one state's extended continental shelf extending within 200 nautical miles of another state appeared not to have been debated during UNCLOS III.Footnote 19 However, the ICJ noted that the purpose of the substantive and procedural conditions for determining the outer limits of the extended continental shelf was to prevent the extended continental shelf from unduly encroaching on the international seabed area (the Area) and its resources, which are the “common heritage of mankind.”Footnote 20 It then assumed that the extended continental shelf would only extend into the Area, not within 200 nautical miles of another state.Footnote 21 To support its assumption, the ICJ reasoned that payments or contributions made under Article 81(2) of UNCLOS with respect to the exploitation of the non-living resources of the extended continental shelf would not achieve the aim of that provision in a situation where the extended continental shelf of one state extended within 200 nautical miles of another state.Footnote 22

On the third point, the ICJ noted that the “vast majority”Footnote 23 of states parties to UNCLOS had made submissions to the CLCS choosing not to assert outer limits of their extended continental shelf within the 200 nautical miles of the baselines of another state.Footnote 24 “Taken as a whole,” the ICJ considered this state practice as constitutive of customary international law, since it was sufficiently widespread, convincing, and uniform, as well as indicative of opinio juris (even though it may have been motivated in part by reasons other than a sense of legal obligation).Footnote 25 In the ICJ's view, this practice also reflected opinio juris, given its extent over a long period of time.Footnote 26 The ICJ then concluded that, under customary international law, a state's entitlement to an extended continental shelf, even if the state concerned can demonstrate its entitlement, may not extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another state.Footnote 27 As a result, if there are no overlapping entitlements over the same maritime areas, then there is no need for delimitation.Footnote 28 Because there was no possibility of an overlapping entitlement/area in the case at hand, the ICJ rejected Nicaragua's request for delimitation.Footnote 29

Based on its answer to the first question, the ICJ did not consider it necessary to address its second question on the criteria, under customary international law, for the determination of the limit of the extended continental shelf.Footnote 30

Conclusion

The ICJ's decision has been criticized by legal scholarsFootnote 31 and questioned by some of the ICJ judgesFootnote 32 on three main grounds.

The first ground is the identification of the opinio juris as a constitutive element of the rule of customary international law in this case.Footnote 33 Judges Tomka, Xue, and Robinson considered that states refraining from claiming an extended continental shelf within 200 miles from the baselines of another state in their submissions to the CLCS might have been motivated by reasons other than a sense of legal obligation.Footnote 34 In particular, a state concerned may want to avoid another state blocking the consideration of its submission by the CLCS if there is a dispute,Footnote 35 thus avoiding the situation where the establishment of the outer limits of its continental shelf remains unresolved.Footnote 36 Hence, the ICJ erred by inferring opinio juris from the practice of those states.

The second ground relates to the implications of the new rule of customary international law on the concept of the “single continental shelf” and the existence of “grey areas.” The rule identified by the ICJ implies that a state's entitlement to a continental shelf based on the distance criterion takes precedence over the entitlement of another state based on the criterion of natural prolongation. This contradicts the concept of the “single continental shelf” upheld by the ICJ (and other international tribunals). Not only does this imply that the former entitlement “expunges” or “trumps” the latter entitlement, but it also suggests that there are two different continental shelves, within and beyond 200 nautical miles, rather than a single one.Footnote 37

The rule that a state's entitlement to an extended continental shelf cannot encroach on the 200 nautical mile zone from the baselines of another state also implies the incompatibility of the “grey areas” with this rule;Footnote 38 and with the idea that the continental shelf regime is incorporated in the EEZ regime (separating seabed and subsoil from superjacent waters within 200 nautical miles would be contrary to the EEZ concept). However, Judge Tomka noted that the Bay of Bengal casesFootnote 39 and the ICJ judgment in Somalia v. Kenya, had recognized the existence of “grey areas”Footnote 40 and, in that sense, the 2023 Judgment departed from the ICJ's and other international tribunals' jurisprudence.Footnote 41Judge Xue also considered that, in those three cases, “the ‘grey area,’ albeit incidental in nature and small in size, is in itself a piece of hard evidence that disproves at least the inseparability of [the continental shelf and the EEZ] in the maritime delimitation.”Footnote 42

The ICJ might have decided that, in the case of opposite coasts, a state's entitlement to an extended continental shelf may not extend within an entitlement to a continental shelf within 200 miles of another state to avoid not only the potential creation of “grey areas,”Footnote 43 but also the creation of potential “complex legal and practical issues” because of the seabed and subsoil being within the national jurisdiction of one state and the superjacent waters being within the national jurisdiction of another state within 200 nautical miles.Footnote 44

In relation to the third ground, the rule identified by the ICJ not only put an additional limit to Nicaragua's entitlement to an extended continental shelf but could also make moot other similar maritime claims, such as in the South China Sea.Footnote 45 Also, it could have implications for maritime delimitation, including the possibility of small maritime features to trump competing claims to extended continental shelves.Footnote 46

13 JULY 2023 JUDGMENT

QUESTION OF THE DELIMITATION OF THE CONTINENTAL SHELF BETWEEN NICARAGUA AND COLOMBIA BEYOND 200 NAUTICAL MILES FROM THE NICARAGUAN COAST

(NICARAGUA v. COLOMBIA)

QUESTION DE LA DÉLIMITATION DU PLATEAU CONTINENTAL ENTRE LE NICARAGUA ET LA COLOMBIE AU-DELÀ DE 200 MILLES MARINS

DE LA CÔTE NICARAGUAYENNE (NICARAGUA c. COLOMBIE)

13 JUILLET 2023 ARRÊT

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Paragraphs

Chronology of the procedure....................[1–20]

I. General background....................[21–26]

II. Overview of the Parties' positions....................[27–34]

III. First question formulated in the Order of 4 October 2022....................[35–79]

A. The preliminary character of the first question....................[37–45]

B. The customary international law applicable to the maritime areas at issue....................[46–53]

C. Under customary international law, may a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of its territorial sea is measured extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State?....................[54–79]

IV. Second question formulated in the Order of 4 October 2022....................[80–82]

V. Consideration of Nicaragua's submissions....................[83–103]

A. The request contained in the first submission made by Nicaragua....................[85–87]

B. The request contained in the second submission made by Nicaragua....................[88–92]

C. The request contained in the third submission made by Nicaragua....................[93–102]

Operative clause....................[104]

2023 YEAR 2023

13 July General List No. 154 13 July 2023

QUESTION OF THE DELIMITATION OF THE CONTINENTAL SHELF BETWEEN NICARAGUA AND COLOMBIA BEYOND 200 NAUTICAL MILES FROM THE NICARAGUAN COAST

(NICARAGUA v. COLOMBIA)

General background — Geography — The Court's 2012 Judgment in Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia) delimiting the Parties' continental shelves and exclusive economic zones up to a 200-nautical-mile limit from Nicaragua's coast — Application filed by Nicaragua on 16 September 2013 — Request to determine maritime boundary in areas of continental shelf beyond the boundaries determined in 2012 Judgment — Delimitation lines proposed by Nicaragua in its written pleadings — The Court's Order of 4 October 2022 — Certain questions of law to be decided first.

*

First question formulated in the Order of 4 October 2022 — Whether a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from its baselines may extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State — Determination of the existence of overlapping entitlements as a first step in any maritime delimitation — Preliminary character of the first question — Must be answered to ascertain whether the Court may proceed to the delimitation requested by Nicaragua.

Customary international law applicable to the maritime areas at issue — Nicaragua is a party to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (“UNCLOS”), Colombia is not — Drawing up of UNCLOS at the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (the “Conference”) — State practice taken into account during the drafting of UNCLOS — Method of negotiation of UNCLOS — Comprehensive and integrated text forming a package deal — Relationship between Part V of UNCLOS on the exclusive economic zone and Part VI on the continental shelf specified in Article 56, paragraph 3, of UNCLOS — Article 56 of UNCLOS reflects customary rules on rights and duties in the exclusive economic zone — Definition of continental shelf in Article 76, paragraph 1, of UNCLOS forms part of customary international law.

Legal régime governing the exclusive economic zone set out in UNCLOS result of a compromise reached at the Conference — Articles 56, 58, 61, 62 and 73 of UNCLOS on rights and duties of coastal States and other States in the exclusive economic zone reflect customary international law — Interrelated nature of legal régimes that govern the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf within 200 nautical miles from a State's baselines — There cannot be an exclusive economic zone without a corresponding continental shelf — Question of “grey area” — Incidental result of adjustment of equidistance line — Circumstances in Bay of Bengal cases distinct from situation in the present case — Criteria for determining outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles were the result of a compromise reached during the final sessions of the Conference — Aim to avoid undue encroachment on maritime areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction (the “Area”) — Text of Article 76 of UNCLOS suggests that States participating in negotiations assumed that extended continental shelf would only extend into maritime areas that would otherwise be located in the Area — Payments in respect of exploitation of the non-living resources of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles — Possibility of one State's extended continental shelf extending within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State apparently not debated during the Conference — Vast majority of States parties to UNCLOS that have made submissions to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (“CLCS”) have not asserted limits that extend within 200 nautical miles of the baselines of another State — Practice of States before the CLCS is indicative of opinio juris — Objections where States have asserted a right to an extended continental shelf encroaching on maritime areas within 200 nautical miles of other States — Practice of States sufficiently widespread and uniform — This State practice may be seen as an expression of opinio juris — Under customary international law, a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from its baselines may not extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State.

*

Second question formulated in the Order of 4 October 2022 — Identification of the criteria under customary international law for the determination of the limit of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles of a State's baselines and question whether paragraphs 2 to 6 of Article 76 of UNCLOS reflect customary international law — No need for the Court to address the second question in light of the answer to the first question.

*

Consideration of Nicaragua's submissions made in its written pleadings.

Request contained in Nicaragua's first submission — Nicaragua proposes co-ordinates for the continental shelf boundary in the area beyond 200 nautical miles from its baselines but within 200 nautical miles from Colombia's baselines — Nicaragua not entitled to an extended continental shelf within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of Colombia's mainland coast — No area of overlapping entitlement to be delimited — Request contained in Nicaragua's first submission cannot be upheld.

Request contained in Nicaragua's second submission — Nicaragua's contention that maritime entitlements of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina should not extend east of the 200-nautical-mile limit of its exclusive economic zone — Nicaragua not entitled to an extended continental shelf within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of San Andrés and Providencia — No area of overlapping entitlement to be delimited — Request contained in Nicaragua's second submission cannot be upheld.

Request contained in Nicaragua's third submission — Effect, if any, of the maritime entitlements of Serranilla, Bajo Nuevo and Serrana on any maritime delimitation between the Parties — Two possibilities regarding Serranilla and Bajo Nuevo — Either they are entitled to exclusive economic zones and continental shelves, or they are not — In either case, no area of overlapping entitlement to be delimited — Effect of Serrana's maritime entitlements determined conclusively in the 2012 Judgment — Request contained in Nicaragua's third submission cannot be upheld.

JUDGMENT

Present: President DONOGHUE; Vice-President GEVORGIAN; Judges TOMKA, ABRAHAM, BENNOUNA, YUSUF, XUE, SEBUTINDE, BHANDARI, ROBINSON, SALAM, IWASAWA, NOLTE, CHARLESWORTH, BRANT; Judges ad hoc MCRAE, SKOTNIKOV;

Registrar Gautier.

In the case concerning the question of the delimitation of the continental shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 nautical miles from the Nicaraguan coast,

between

the Republic of Nicaragua,

represented by

HE Mr Carlos José Argüello Gómez, Permanent Representative of the Republic of Nicaragua to the international organizations based in the Kingdom of the Netherlands, member of the International Law Commission,

as Agent and Counsel;

Mr Alex Oude Elferink, Director, Netherlands Institute for the Law of the Sea, Professor of International Law of the Sea at Utrecht University,

Mr Vaughan Lowe, KC, Emeritus Chichele Professor of Public International Law, University of Oxford, member of the Institut de droit international, member of the Bar of England and Wales,

Mr Alain Pellet, Emeritus Professor of the University Paris Nanterre, former Chairman of the International Law Commission, President of the Institut de droit international,

as Counsel and Advocates;

Ms Claudia Loza Obregon, Legal Adviser, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Nicaragua,

Mr Benjamin Samson, Centre de droit international de Nanterre (CEDIN), University Paris Nanterre,

as Assistant Counsel;

Mr Robin Cleverly, MA, DPhil, CGeol, FGS, Law of the Sea Consultant, Marbdy Consulting Ltd,

as Scientific and Technical Adviser;

Ms Sherly Noguera de Argüello, Consul General of the Republic of Nicaragua,

as Administrator,

and

the Republic of Colombia,

represented by

HE Mr Eduardo Valencia-Ospina, former Registrar and Deputy-Registrar of the International Court of Justice, former member, Special Rapporteur and Chairman of the International Law Commission,

as Agent and Counsel;

HE Ms Carolina Olarte-Bácares, Dean of the School of Law at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, Ambassador of the Republic of Colombia to the Kingdom of the Netherlands,

HE Ms Elizabeth Taylor Jay, former Ambassador of the Republic of Colombia to the Republic of Kenya, former Permanent Representative of the Republic of Colombia to the United Nations Environment Programme and the United Nations Human Settlements Programme,

as Co-Agents;

HE Mr Álvaro Leyva Durán, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Colombia,

HE Mr Everth Hawkins Sjogreen, Governor of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina, Republic of Colombia,

as National Authorities;

Mr W. Michael Reisman, Myres S. McDougal Professor Emeritus of International Law, Yale University, member of the Institut de droit international,

Sir Michael Wood, KCMG, KC, former member of the International Law Commission, member of the Bar of England and Wales,

Mr Rodman R. Bundy, former avocat à la Cour d'appel de Paris, member of the Bar of the State of New York, partner at Squire Patton Boggs LLP, Singapore,

Mr Jean-Marc Thouvenin, Professor at the University Paris Nanterre, Secretary-General of the Hague Academy of International Law, associate member of the Institut de droit international, member of the Paris Bar, Sygna Partners,

Ms Laurence Boisson de Chazournes, Professor of International Law and International Organization at the University of Geneva, Professor at the Collège de France (2022-2023), member of the Institut de droit international,

Mr Lorenzo Palestini, Lecturer at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies and at the University of Geneva,

as Counsel and Advocates;

Mr Andrés Villegas Jaramillo, Co-ordinator, Group of Affairs before the International Court of Justice at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Colombia, associate of the Instituto Hispano-Luso-Americano de Derecho Internacional,

Mr Makane Moïse Mbengue, Professor at the University of Geneva, Director of the Department of Public International Law and International Organization, associate member of the Institut de droit international,

Mr Eran Sthoeger, Esq., Adjunct Professor of International Law at Brooklyn Law School and Seton Hall Law School, member of the Bar of the State of New York,

Mr Alvin Yap, Advocate and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Singapore, Squire Patton Boggs LLP, Singapore,

Mr Gershon Hasin, Visiting Lecturer in Law at Yale University,

Mr Gabriel Cifuentes, adviser to the Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Colombia, as Counsel;

Ms Jenny Bowie Wilches, First Secretary, Embassy of the Republic of Colombia in the Kingdom of the Netherlands,

Ms Viviana Andrea Medina Cruz, Second Secretary, Embassy of the Republic of Colombia in the Kingdom of the Netherlands,

Mr Raúl Alfonso Simancas Gómez, Third Secretary, Embassy of the Republic of Colombia in the Kingdom of the Netherlands,

Mr Oscar Casallas Méndez, Third Secretary, Group of Affairs before the International Court of Justice,

Mr Carlos Colmenares Castro, Third Secretary, Group of Affairs before the International Court of Justice, as representatives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Colombia;

Rear Admiral Ernesto Segovia Forero, Chief of Naval Operations,

CN Hermann León, Delegate of Colombia to the International Maritime Organization,

CN William Pedroza, National Navy of Colombia, Director of Maritime and Fluvial Interests Office,

as representatives of the Navy of the Republic of Colombia;

Mr Lindsay Parson, Geologist, Director of Maritime Zone Solutions Ltd, United Kingdom, former member and Chair of the United Nations International Seabed Authority's Legal and Technical Commission,

Mr Peter Croker, Geophysicist, Consultant at The M Horizon (UK) Ltd, former Chair of the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf,

Mr Walter R. Roest, Geophysicist, Director of Roest Consultant EIRL, France, member of the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf,

Mr Scott Edmonds, Cartographer, Director of International Mapping, Mr Thomas Frogh, Cartographer, International Mapping,

as Technical Advisers,

The Court,

composed as above,

after deliberation,

delivers the following Judgment:

1. On 16 September 2013, the Government of the Republic of Nicaragua (hereinafter “Nicaragua”) filed in the Registry of the Court an Application instituting proceedings against the Republic of Colombia (hereinafter “Colombia”) with regard to a dispute concerning “the delimitation of the boundaries between, on the one hand, the continental shelf of Nicaragua beyond the 200-nautical-mile limit from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of Nicaragua is measured, and on the other hand, the continental shelf of Colombia”.

2. In its Application, Nicaragua sought to found the jurisdiction of the Court on Article XXXI of the American Treaty on Pacific Settlement signed on 30 April 1948, officially designated, according to Article LX thereof, as the “Pact of Bogotá”.

3. In accordance with Article 40, paragraph 2, of the Statute of the Court, the Registrar immediately communicated the Application to the Government of Colombia. He also notified the Secretary-General of the United Nations of the filing of the Application by Nicaragua.

4. Pursuant to Article 40, paragraph 3, of the Statute of the Court, the Registrar notified the Members of the United Nations through the Secretary-General of the filing of the Application, by transmission of the printed bilingual text.

5. Since the Court included upon the Bench no judge of the nationality of either Party, each Party proceeded to exercise the right conferred upon it by Article 31, paragraph 3, of the Statute to choose a judge ad hoc to sit in the case. Nicaragua chose Mr Leonid Skotnikov. Colombia first chose Mr Charles N. Brower, who resigned on 5 June 2022, and subsequently Mr Donald McRae.

6. By an Order of 9 December 2013, the Court fixed 9 December 2014 and 9 December 2015 as the respective time-limits for the filing of a Memorial by Nicaragua and a Counter-Memorial by Colombia.

7. On 14 August 2014, before the expiry of the time-limit for the filing of the Memorial of Nicaragua, Colombia, referring to Article 79 of the Rules of Court of 14 April 1978 as amended on 1 February 2001, raised preliminary objections to the jurisdiction of the Court and to the admissibility of the Application. By an Order of 19 September 2014, the Court, noting that by virtue of Article 79, paragraph 5, of the Rules of Court the proceedings on the merits were suspended, fixed 19 January 2015 as the time-limit for the presentation by Nicaragua of a written statement of its observations and submissions on the preliminary objections raised by Colombia. Nicaragua filed its statement within the time-limit thus fixed.

8. By a letter dated 10 November 2014, pursuant to the instructions of the Court under Article 43, paragraph 1, of the Rules of Court, the Registrar addressed to States parties to the Pact of Bogotá the notification provided for in Article 63, paragraph 1, of the Statute of the Court. In accordance with the provisions of Article 69, paragraph 3, of the Rules of Court, the Registrar also addressed to the Organization of American States (hereinafter the “OAS”) the notification provided for in Article 34, paragraph 3, of the Statute. By letter dated 5 January 2015, the Secretary-General of the OAS indicated that the Organization did not intend to present any observations in writing within the meaning of Article 69, paragraph 3, of the Rules of Court.

9. By a letter dated 17 February 2015, the Government of the Republic of Chile (hereinafter “Chile”), referring to Article 53, paragraph 1, of the Rules of Court, asked to be furnished with copies of the pleadings and documents annexed in the case. Having ascertained the views of the Parties in accordance with that same provision, the President of the Court decided to grant that request. The Registrar duly communicated that decision to the Government of Chile and to the Parties. Copies of the preliminary objections raised by Colombia and the written statement of its observations and submissions thereon filed by Nicaragua were therefore communicated to Chile.

10. Public hearings on the preliminary objections raised by Colombia were held on 5, 6, 7 and 9 October 2015. In its Judgment of 17 March 2016, the Court found that it had jurisdiction, on the basis of Article XXXI of the Pact of Bogotá, to entertain the first request put forward by Nicaragua in its Application (see paragraph 18 below), asking the Court to determine “[t]he precise course of the maritime boundary between Nicaragua and Colombia in the areas of the continental shelf which appertain to each of them beyond the boundaries determined by the Court in its Judgment of 19 November 2012” in the case concerning Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia), and that this request was admissible (Question of the Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Nicaraguan Coast (Nicaragua v. Colombia), Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2016 (I), p. 140, para. 126).

11. By an Order of 28 April 2016, the Court fixed 28 September 2016 and 28 September 2017, respectively, as the new time-limits for the filing of a Memorial by Nicaragua and a Counter-Memorial by Colombia. These pleadings were filed within the time-limits thus fixed. Along with its Memorial, Nicaragua also provided to the Court copies of its full submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (hereinafter the “CLCS” or the “Commission”), explaining that this submission was part of its Memorial and that it was classified as confidential in accordance with the rules contained in Annex II to the Rules of Procedure of the CLCS.

12. By letters dated 6 October 2016 and 22 November 2016, respectively, the Government of the Republic of Costa Rica (hereinafter “Costa Rica”) and the Government of the Republic of Panama (hereinafter “Panama”), referring to Article 53, paragraph 1, of the Rules of Court, asked to be furnished with copies of the pleadings and documents annexed in the case. Having ascertained the views of the Parties in accordance with the same provision, the Court granted those requests, with the exception of the submission of Nicaragua to the CLCS, which would not be provided to Costa Rica and Panama. The Registrar duly communicated those decisions to Costa Rica and Panama and to the Parties. A copy of Nicaragua's Memorial, not including said submission, was also made available to Chile (see paragraph 9 above).

13. By an Order of 8 December 2017, the Court authorized the submission of a Reply by Nicaragua and a Rejoinder by Colombia, and fixed 9 July 2018 and 11 February 2019 as the respective time-limits for the filing of those pleadings. The Reply of Nicaragua and the Rejoinder of Colombia were filed within the time-limits thus fixed.

14. In an Order of 4 October 2022, the Court indicated that, in the circumstances of the case, before proceeding to any consideration of technical and scientific questions in relation to the delimitation of the continental shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of Nicaragua is measured, it was necessary to decide on certain questions of law, after hearing the Parties thereon. Accordingly, the Court decided that,

“at the forthcoming oral proceedings in the case, the Republic of Nicaragua and the Republic of Colombia shall present their arguments exclusively with regard to the following two questions:

(1) Under customary international law, may a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of its territorial sea is measured extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State?

(2) What are the criteria under customary international law for the determination of the limit of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured and, in this regard, do paragraphs 2 to 6 of Article 76 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea reflect customary international law?” (Question of the Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Nicaraguan Coast (Nicaragua v. Colombia), Order of 4 October 2022.)

15. Having ascertained the views of the Parties and in light of the scope of the oral proceedings, the Court decided, pursuant to Article 53, paragraph 2, of the Rules of Court, that copies of the written pleadings and documents annexed would not be made accessible to the public at the time of the opening of the oral proceedings.

16. Public hearings on the two questions formulated by the Court in its Order of 4 October 2022 (see paragraph 14 above) were held on 5, 6, 7 and 9 December 2022, at which the Court heard the oral arguments and replies of:

For Nicaragua: HE Mr Carlos José Argüello Gómez,

Mr Vaughan Lowe,

Mr Alex Oude Elferink,

Mr Alain Pellet.

For Colombia: HE Mr Eduardo Valencia-Ospina,

Sir Michael Wood,

Mr Rodman Bundy,

Mr Lorenzo Palestini,

Mr Jean-Marc Thouvenin,

Ms Laurence Boisson de Chazournes.

17. At the hearings, a Member of the Court put a question to Colombia, to which a reply was given orally in accordance with Article 61, paragraph 4, of the Rules of Court. Nicaragua submitted written comments on the oral reply provided by Colombia on 15 December 2022.

*

18. In the Application, the following claims were made by Nicaragua: “Nicaragua requests the Court to adjudge and declare:

1. First: The precise course of the maritime boundary between Nicaragua and Colombia in the areas of the continental shelf which appertain to each of them beyond the boundaries determined by the Court in its Judgment of 19 November 2012.

2. Second: The principles and rules of international law that determine the rights and duties of the two States in relation to the area of overlapping continental shelf claims and the use of its resources, pending the delimitation of the maritime boundary between them beyond 200 nautical miles from Nicaragua's coast.”

19. In the written proceedings, the following submissions were presented by the Parties:

On behalf of the Government of Nicaragua,

in the Memorial:

“For the reasons given in the present Memorial, the Republic of Nicaragua requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:

1. The maritime boundary between Nicaragua and Colombia in the areas of the continental shelf which appertain to each of them beyond the boundary determined by the Court in its Judgment of 19 November 2012, follows geodetic lines connecting the points with the following co-ordinates:

2. The islands of San Andrés and Providencia are entitled to a continental shelf up to a line consisting of 200 nm arcs from the baselines from which the territorial sea of Nicaragua is measured connecting the points with the following co-ordinates:

3. Serranilla and Bajo Nuevo are enclaved and granted a territorial sea of twelve nautical miles.”

in the Reply:

“For the reasons given in the Memorial and the present Reply, the Republic of Nicaragua requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:

1. The maritime boundary between Nicaragua and Colombia in the areas of the continental shelf which appertain to each of them beyond the boundary determined by the Court in its Judgment of 19 November 2012, follows geodetic lines connecting the points with the following co-ordinates:

2. The islands of San Andrés and Providencia are entitled to a continental shelf up to a line consisting of 200 nm arcs from the baselines from which the territorial sea of Nicaragua is measured connecting the points with the following co-ordinates:

3. Serranilla and Bajo Nuevo are enclaved and granted a territorial sea of twelve nautical miles, and Serrana is enclaved as per the Court's November 2012 Judgment.”

On behalf of the Government of Colombia,

in the Counter-Memorial:

“[F]or the reasons set out in this Counter-Memorial, and reserving the right to amend or supplement these Submissions, Colombia respectfully requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:Nicaragua's request for a delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from its coast is rejected with prejudice.”

in the Rejoinder:

“[F]or the reasons set out in its Counter-Memorial and Rejoinder, and reserving the right to amend or supplement these Submissions, Colombia respectfully requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:

Nicaragua's request for a delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from its coast is rejected with prejudice.”

20. At the oral proceedings, the following submissions were presented by the Parties:

On behalf of the Government of Nicaragua,

“In the case concerning The Question of the Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Nicaraguan Coast (Nicaragua v. Colombia), for the reasons explained in the Written and Oral phase, Nicaragua respectfully requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:

I. The response to the questions of law is in the affirmative:

A. Under customary international law a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured may extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State.

B. Paragraphs 2 to 6 of Article 76 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea reflect customary international law.

II. Nicaragua respectfully requests the Court to proceed to fix a timetable to hear and decide upon all of the outstanding request in Nicaragua's pleadings.

Nicaragua, formally reserves its right to complete its Final Submissions in view of the factual circumstances of the case as decided by the Court in its Order of 4 October 2022.”

On behalf of the Government of Colombia,

“With respect to the Question of the Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Nicaraguan Coast (Nicaragua v. Colombia), having regard to the Order dated 4 October 2022 and the questions of law contained therein, Colombia respectfully requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:

1. In relation to the first question:

i. Under customary international law, a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of its territorial sea is measured cannot extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State.

2. In relation to the second question:

i. Under customary international law, there are no criteria for the determination of the limit of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured whenever the outer limit of said continental shelf is located within the 200-nautical-mile zone of another State.

ii. Paragraphs 2 to 6 of Article 76 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea do not reflect customary international law.

Furthermore, considering that the answers to these two questions govern all of Nicaragua's submissions as set out during the course of the proceedings, Colombia further requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:

3. Nicaragua's request for a delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from its coast is rejected with prejudice.

4. Consequently, Nicaragua's request for the fixing of a timetable to hear and decide upon all the outstanding requests in Nicaragua's pleadings is rejected.”

*

* *

I. GENERAL BACKGROUND

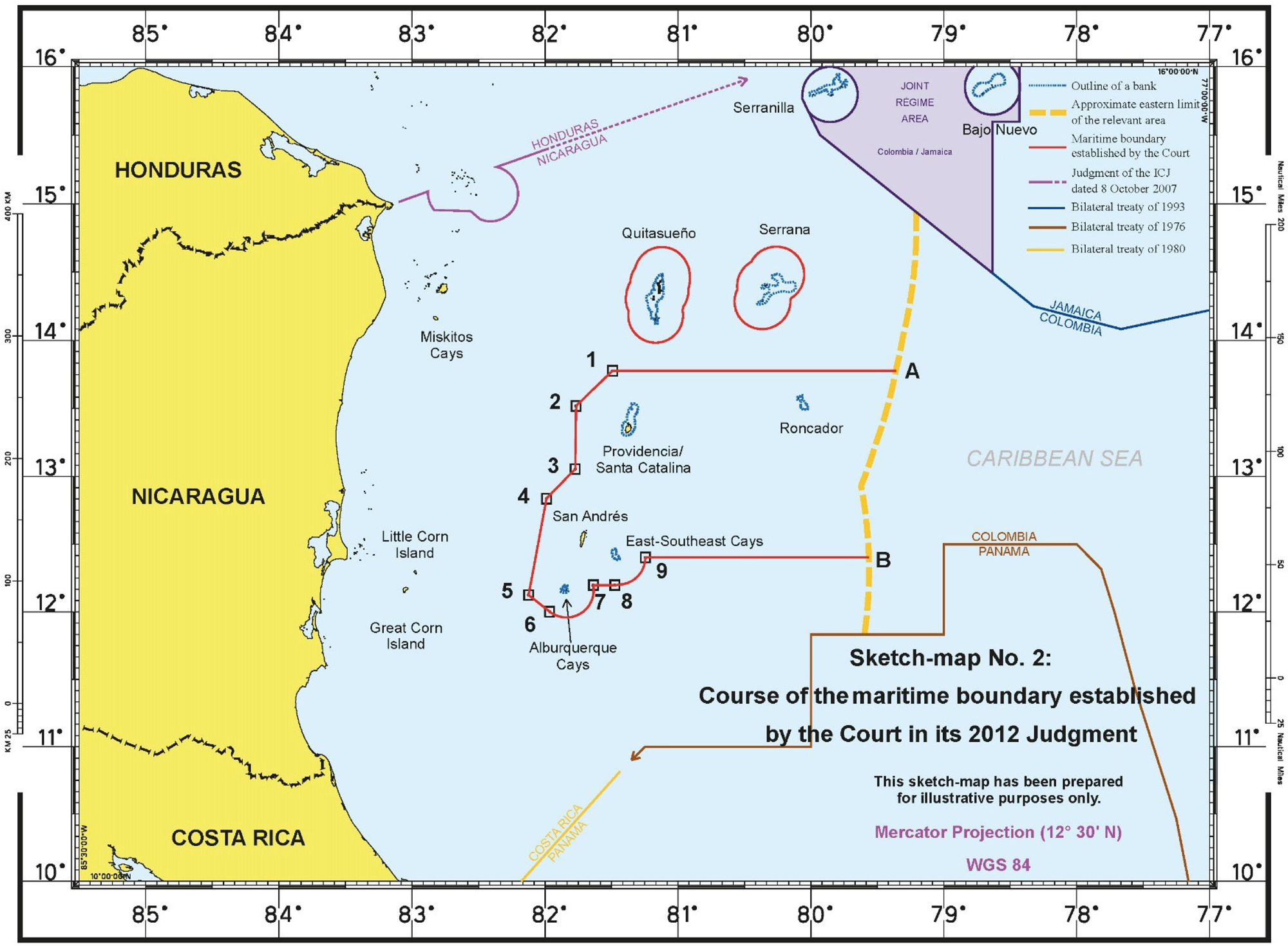

21. The maritime areas with which the present proceedings are concerned are located in the Caribbean Sea, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean partially enclosed to the north and east by a number of islands, and bounded to the south and west by South and Central America. Nicaragua's eastern coast faces the south-western part of the Caribbean Sea. To the north of Nicaragua lies Honduras and to the south lie Costa Rica and Panama. To the north-east, Nicaragua faces Jamaica, and to the east, it faces the mainland coast of Colombia. Colombia is situated to the south of the Caribbean Sea. On its Caribbean front, Colombia is bordered to the west by Panama and to the east by Venezuela. The Colombian islands of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina lie in the south-west of the Caribbean Sea, approximately 100 to 150 nautical miles to the east of the Nicaraguan coast. (For the general geography of the area, see sketch-map No. 1.)

Sketch-map No. 1: General Geography

22. On 6 December 2001, Nicaragua filed in the Registry of the Court an Application instituting proceedings against Colombia in respect of a dispute consisting of “a group of related legal issues subsisting” between the two States “concerning title to territory and maritime delimitation” in the western Caribbean (case concerning Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia)).

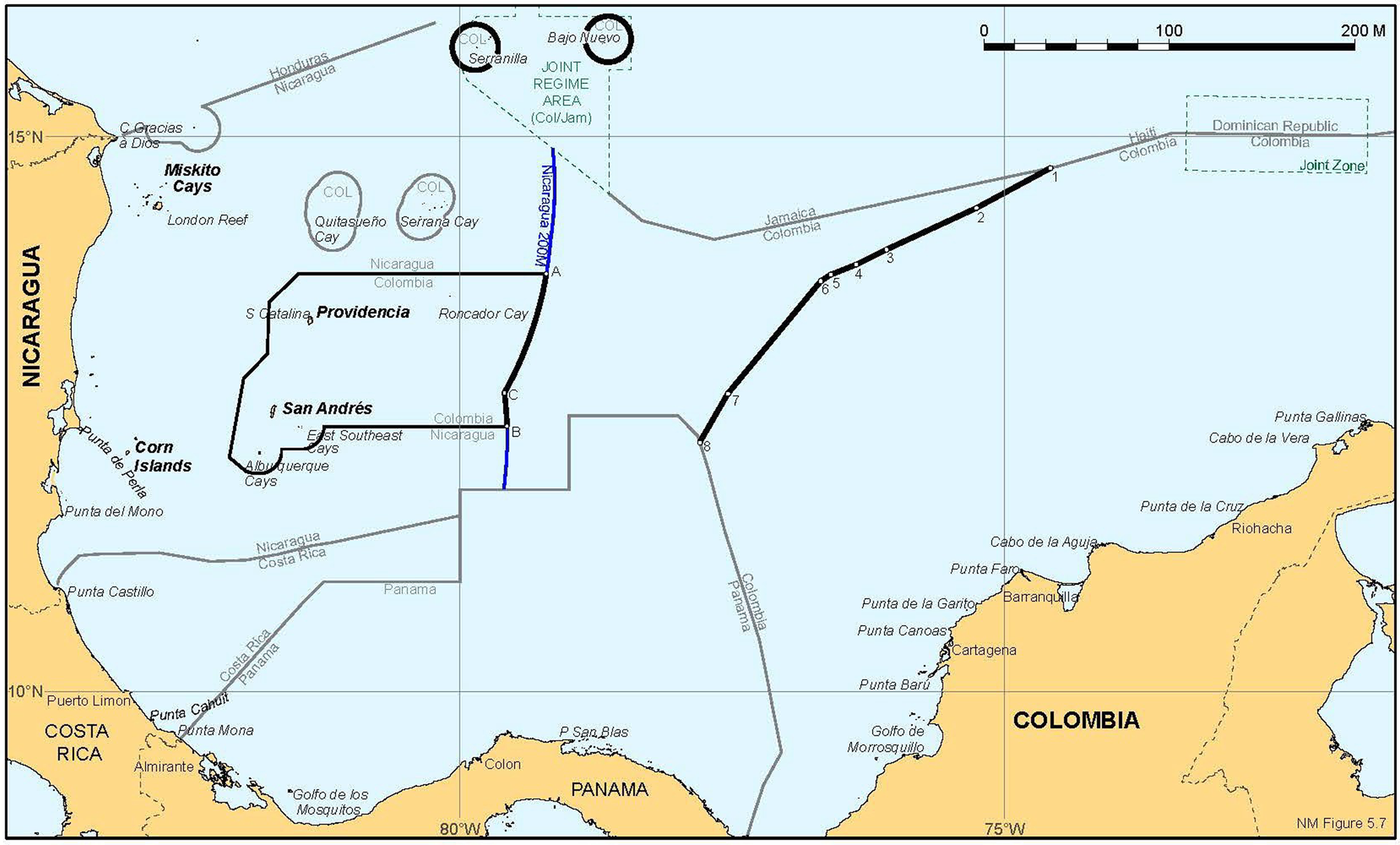

23. In the Judgment rendered by the Court on 19 November 2012 in.the case concerning Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia) (hereinafter the “2012 Judgment”), the Court decided that Colombia “has sovereignty over the islands at Alburquerque, Bajo Nuevo, East-Southeast Cays, Quitasueño, Roncador, Serrana and Serranilla” (I.C.J. Reports 2012 (II), p. 718, para. 251, subpara. 1). The Court also established a single maritime boundary delimiting the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zones of Nicaragua and Colombia up to the 200-nautical-mile limit from the baselines from which the territorial sea of Nicaragua is measured (ibid., pp. 719-720, para. 251, subpara. 4). The Court, however, noted in its reasoning that, since Nicaragua had not yet notified the Secretary-General of the United Nations of the location of those baselines under Article 16, paragraph 2, of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (hereinafter “UNCLOS” or the “Convention”), the precise location of the eastern endpoints of the maritime boundary could not be determined and was therefore depicted only approximately on the sketch-map included at page 714 of that Judgment (ibid., p. 713, para. 237). (For the course of the maritime boundary established by the Court in its 2012 Judgment, see sketch-map No. 2.)

Sketch-map No. 2: Course of the maritime boundary established by the Court in its 2012 Judgment 28.

24. In the 2012 Judgment, the Court further found that it could not uphold Nicaragua's claim contained in its final submission I (3), requesting that the Court adjudge and declare that

“[t]he appropriate form of delimitation, within the geographical and legal framework constituted by the mainland coasts of Nicaragua and Colombia, is a continental shelf boundary dividing by equal parts the overlapping entitlements to a continental shelf of both Parties” (Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2012 (II), p. 636, para. 17, and p. 719, para. 251, subpara. 3).

In particular, the Court noted that,

“since Nicaragua . . . ha[d] not established that it ha[d] a continental margin that extends far enough to overlap with Colombia's 200-nautical-mile entitlement to the continental shelf, measured from Colombia's mainland coast, the Court [was] not in a position to delimit the continental shelf boundary between Nicaragua and Colombia, as requested by Nicaragua, even using the general formulation proposed by it” (ibid., p. 669, para. 129).

The Court observed in this regard that Nicaragua had submitted to the CLCS only “Preliminary Information” which “[fell] short of meeting the requirements for information on the limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles” to be submitted under Article 76, paragraph 8, of UNCLOS (ibid., p. 669, para. 127).

25. On 24 June 2013, in accordance with Article 76, paragraph 8, of UNCLOS, Nicaragua presented its full submission to the CLCS regarding the limits of its continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of its territorial sea is measured.

26. On 16 September 2013, Nicaragua filed the Application instituting the current proceedings, requesting the Court to adjudge and declare the precise course of the maritime boundary between Nicaragua and Colombia in the areas of the continental shelf which appertain to each of them beyond the boundaries determined by the Court in its 2012 Judgment (see paragraph 1 above).

Both Parties have adduced extensive technical and scientific evidence as to whether Nicaragua has established an entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured (also referred to as an “extended continental shelf”) and, if so, the precise outer limits of that continental shelf.

II. OVERVIEW OF THE PARTIES' POSITIONS

27. Nicaragua argues that it has an entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles of its coast. In order to substantiate its claim, Nicaragua relies on the submission that it presented to the CLCS on 24 June 2013, which, in its view, contains “complete technical information” that enables the Commission to review that submission and make its recommendations under Article 76, paragraph 8, of UNCLOS on the outer limits of Nicaragua's continental shelf. Nicaragua contends that it has established the existence of a natural prolongation of its land territory up to the outer edge of the continental margin and that there is both geological and geomorphological continuity between its landmass and the sea-bed and subsoil beyond 200 nautical miles from its baselines.

28. Nicaragua defines the outer edge of the continental margin, wherever the margin extends beyond 200 nautical miles of its coast, by reference to the formulae and criteria contained in Article 76, paragraphs 4 to 6, of UNCLOS. It asserts that the CLCS applies these provisions to determine the existence of a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles. According to Nicaragua, Article 76, paragraphs 2 to 6, of UNCLOS reflect customary international law.

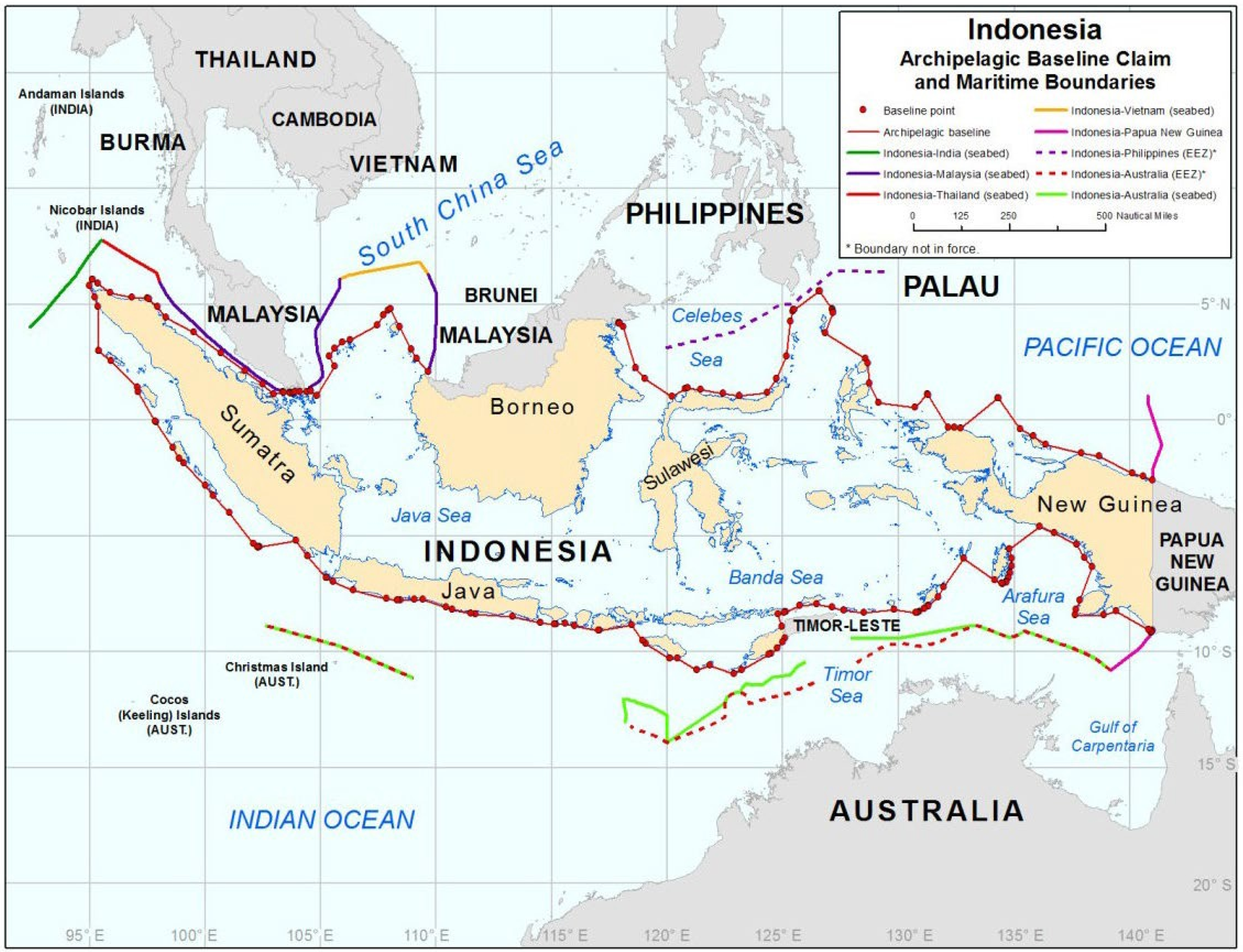

29. Nicaragua notes that Colombia only claims, with respect to its mainland, a continental shelf up to 200 nautical miles from its baselines. Nicaragua proposes, with respect to Colombia's mainland, a provisional delimitation line which Nicaragua refers to as the “provisional mainland-mainland delimitation line”. This line divides equally the area of overlap between the 200-nautical-mile limit of the continental shelf entitlement generated by Colombia's mainland coast and the outer limits of the extended continental shelf as described by Nicaragua in its submission to the CLCS. That line is depicted in figure 5.1 of Nicaragua's Memorial, which is reproduced below.

30. With respect to the entitlement derived from Colombian islands, Nicaragua contends that only the maritime features of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina qualify as islands entitled to a continental shelf in accordance with the customary rule reflected in Article 121, paragraph 2, of UNCLOS, whereas Quitasueño, Alburquerque, Bajo Nuevo, East-Southeast Cays, Roncador, Serrana and Serranilla fall under the definition of “rocks” under customary international law reflected in Article 121, paragraph 3, of UNCLOS and do not generate any entitlement to a continental shelf. Nicaragua considers that San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina are situated on the same continental margin as Nicaragua's mainland and hence could have a potential continental shelf entitlement beyond 200 nautical miles to the edge of that continental margin. In Nicaragua's view, however, the continental shelf of these islands should not extend east of the 200-nautical-mile limit from Nicaragua's baselines because the 2012 Judgment already allocated these islands continental shelf rights that are very substantial in relation to their limited size. Thus, Nicaragua is of the view that these islands are entitled to a continental shelf up to a line consisting of 200-nautical-mile arcs from the baselines from which the territorial sea of Nicaragua is measured connecting points A, C and B, the co-ordinates of which are indicated in the submissions presented by Nicaragua in its Memorial and reiterated in its Reply (see paragraph 19 above). Nicaragua also considers that the Colombian maritime features of Serranilla Cay and Bajo Nuevo should be afforded only a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea. The final delimitation proposed by Nicaragua is depicted in figure 7.1. of its Reply, which is reproduced below.

Map showing the “provisional mainland-mainland delimitation line” proposed by Nicaragua

(Source: Nicaragua's Memorial, figure 5.1, p. 128)

*

31. Colombia asks the Court to reject Nicaragua's request for a delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles of the latter's coast. It argues in particular that, as a matter of customary international law, a State may not claim a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from its baselines that encroaches on another State's entitlement to a 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone and continental shelf measured from its mainland coast and islands.

32. With respect to the alleged entitlement of Nicaragua to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles of Nicaragua's coast, Colombia argues that the Applicant erroneously assumes that its submission to the CLCS is in itself proof of the existence of its extended continental shelf. According to Colombia, Article 76, paragraphs 2 to 6, which set out precise scientific and technical formulae for fixing limits beyond which an extended continental shelf may not be claimed, do not reflect customary international law. The Respondent contends that a coastal State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles must be based on the natural prolongation of its land territory as evidenced by the physical characteristics of the shelf based on geological and geomorphological factors. In this regard, Colombia argues that Nicaragua fails to demonstrate with scientific certainty the existence of the natural prolongation of its land territory beyond 200 nautical miles of its coast. Colombia claims that there are a number of fundamental geomorphological disruptions and geological discontinuities in the physical continental shelf that terminate the natural prolongation of Nicaragua's land territory well before the 200-nautical-mile limit from the Nicaraguan coast is reached.

Map showing the final delimitation proposed by Nicaragua

(Source: Nicaragua's Reply, figure 7.1, p. 208)

33. Turning to its own entitlements, Colombia alleges that, in conformity with customary international law, both its mainland and its islands are entitled to a 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone with its “attendant” continental shelf. It recalls that, in the 2012 Judgment, the Court ruled that San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina generated a territorial sea, an exclusive economic zone and a continental shelf, and that they possessed substantial entitlements to the east of the 200-nautical-mile line from Nicaragua's baselines. Colombia further asserts that Roncador, Serrana, Serranilla and Bajo Nuevo are not rocks and are thus entitled to an exclusive economic zone with its “attendant” continental shelf, including in areas lying more than 200 nautical miles from Nicaragua's baselines. It contends that all these islands are capable of sustaining human habitation or economic life of their own. It adds that, even if Serrana, Roncador, Serranilla and Bajo Nuevo were deemed not to be entitled to an exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, Nicaragua's claim would still fail because its extended continental shelf cannot “leapfrog” over or “tunnel” under the exclusive economic zone and “attendant” continental shelf of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina.

* *

34. In its Order of 4 October 2022, the Court stated that, in the circumstances of the case, it was first necessary to decide on certain questions of law, after hearing the Parties thereon, and thus posed two questions to the Parties (see paragraph 14 above). The Court will examine the first question (Part III) before turning to the second question (Part IV). It will then consider the requests contained in Nicaragua's submissions (Part V).

III. FIRST QUESTION FORMULATED IN THE ORDER OF 4 OCTOBER 2022

35. The Court recalls that the first question formulated in the Order of 4 October 2022 (hereinafter the “first question”) is worded as follows:

“Under customary international law, may a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of its territorial sea is measured extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State?” (Question of the Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Nicaraguan Coast (Nicaragua v. Colombia), Order of 4 October 2022.)

36. The Court will begin by considering the preliminary character of the first question (Section A). It will then determine the customary international law applicable in this case to the maritime areas at issue (Section B), before responding to the first question (Section C).

A. The preliminary character of the first question

37. The Court recalls that, in its Application of 16 September 2013, Nicaragua instituted proceedings against Colombia with regard to a dispute concerning

“the delimitation of the boundaries between, on the one hand, the continental shelf of Nicaragua beyond the 200-nautical-mile limit from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of Nicaragua is measured, and on the other hand, the continental shelf of Colombia”.

38. In its Order of 4 October 2022, the Court considered that, in the circumstances of the case,

“before proceeding to any consideration of technical and scientific questions in relation to the delimitation of the continental shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of Nicaragua is measured, . . . it [was] necessary to decide on certain questions of law, after hearing the Parties thereon” (Question of the Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Nicaraguan Coast (Nicaragua v. Colombia), Order of 4 October 2022).

39. The Court notes that, while the Parties agree that the first question posed by the Court arises in the particular factual context of the present case, the Parties have approached this question differently.

40. Nicaragua contends that there is an overlap between its own entitlement to an extended continental shelf and Colombia's entitlement to a continental shelf within 200 nautical miles of the latter's coast and that, therefore, the Court must proceed to an equitable delimitation. According to Nicaragua, it is this overlap that necessitates the delimitation of maritime zones in the area in which the Parties have competing entitlements.

41. Colombia, for its part, considers that a State must first establish that it has a legal title to a certain maritime area that overlaps with an area that may be claimed by another State, before the principles and rules of maritime delimitation come into play. In Colombia's view, it is not delimitation that generates a legal title, but rather a legal title that gives rise to the need for delimitation.

42. As the Court has indicated previously, “[a]n essential step in any delimitation is to determine whether there are entitlements, and whether they overlap” (Maritime Delimitation in the Indian Ocean (Somalia v. Kenya), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2021, p. 276, para. 193; see Continental Shelf (Tunisia/Libyan Arab Jamahiriya), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1982, p. 42, para. 34). Determining whether there is any area of overlap between the entitlements of two States, each founded on a distinct legal title, is the first step in any maritime delimitation, because “the task of delimitation consists in resolving the overlapping claims by drawing a line of separation of the maritime areas concerned” (Maritime Delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v. Ukraine), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2009, p. 89, para. 77).

43. Therefore, the first question has a preliminary character in the sense that it must be answered in order to ascertain whether the Court may proceed to the delimitation requested by Nicaragua and, consequently, whether it is necessary to consider the scientific and technical questions that would arise for the purposes of such a delimitation.

44. The Court asked the Parties to base their arguments on customary international law, which is applicable to the present case because, unlike Nicaragua, Colombia is not a party to UNCLOS.

45. The Court will now determine the customary international law applicable to the maritime areas at issue, namely the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf.

B. The customary international law applicable to the maritime areas at issue

46. The Court recalls that “the material of customary international law is to be looked for primarily in the actual practice and opinio juris of States”, and that “multilateral conventions may have an important role to play in recording and defining rules deriving from custom, or indeed in developing them” (Continental Shelf (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya/Malta), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1985, pp. 29-30, para. 27; see also North Sea Continental Shelf (Federal Republic of Germany/Denmark; Federal Republic of Germany/Netherlands), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1969, p. 42, para. 73).

47. UNCLOS was drawn up at the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, which was held over a period of nine years, from December 1973 until the adoption of the Convention in Montego Bay on 10 December 1982. As is indicated in the preamble of UNCLOS, the objective of the Convention was to achieve “the codification and progressive development of the law of the sea”. Even prior to the conclusion of the negotiations, certain aspects of the legal régimes governing the maritime areas of coastal States, notably the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zone, were reflected in State practice, primarily through declarations, laws and regulations. This practice was taken into account during the drafting of the Convention. A very large number of States have since become parties to UNCLOS, which has significantly contributed to the crystallization of certain customary rules.

48. As recognized in the preamble to the Convention, “the problems of ocean space are closely related and need to be considered as a whole”. The method of negotiation at the Conference was designed against this background and had the aim of achieving consensus through a series of provisional and interdependent texts on the various questions at issue that resulted in a comprehensive and integrated text forming a package deal.

49. The integrated character of the various parts of the Convention is particularly evident in relation to Part V of UNCLOS, which concerns the exclusive economic zone, and Part VI, which concerns the continental shelf. The relationship between these two parts is specified in Article 56, paragraph 3. This Article provides:

“1. In the exclusive economic zone, the coastal State has:

(a) sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the sea-bed and of the sea-bed and its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy from the water, currents and winds;

(b) jurisdiction as provided for in the relevant provisions of this Convention with regard to:

(i) the establishment and use of artificial islands, installations and structures;

(ii) marine scientific research;

(iii) the protection and preservation of the marine environment;

(c) other rights and duties provided for in this Convention.

2. In exercising its rights and performing its duties under this Convention in the exclusive economic zone, the coastal State shall have due regard to the rights and duties of other States and shall act in a manner compatible with the provisions of this Convention.

3. The rights set out in this article with respect to the sea-bed and subsoil shall be exercised in accordance with Part VI.”

50. In the case concerning Alleged Violations of Sovereign Rights and Maritime Spaces in the Caribbean Sea (Nicaragua v. Colombia), the Court concluded that Article 56 reflects customary rules on the rights and duties in the exclusive economic zone of coastal States (Judgment of 21 April 2022, para. 57).

51. The Court turns next to the continental shelf, which is defined in Article 76, paragraph 1, of UNCLOS:

“The continental shelf of a coastal State comprises the sea-bed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin, or to a distance of 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured where the outer edge of the continental margin does not extend up to that distance.”

52. The Court recalls that this definition forms part of customary international law (Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2012 (II), p. 666, para. 118).

53. In view of the foregoing, the Court will consider whether, under customary international law, a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of its territorial sea is measured may extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State.

C. Under customary international law, may a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of its territorial sea is measured extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State?

54. The Parties disagree as to whether a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of its territorial sea is measured may extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State.

55. Nicaragua argues that a State's entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles may extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State.

56. Nicaragua asserts that the continental shelf and the rights relating to it automatically appertain to the coastal State, without there being any need for that State to exercise or declare those rights, which is not the case for the exclusive economic zone. According to the Applicant, there is no rule in customary international law, or in UNCLOS, that makes an exclusive economic zone an ipso facto and ab initio appurtenance of every coastal State.

57. Nicaragua acknowledges that, where there is an overlap between a State's continental shelf based on natural prolongation and another State's 200-nautical-mile zone, States have in general preferred to have a single maritime boundary rather than have any part of the continental shelf of one State lie within the 200-nautical-mile zone of the other. It adds, however, that this practice is not proof of a customary norm in this regard, given the lack of opinio juris. Nicaragua argues that the practice of States that refrain from asserting, in their submissions to the CLCS, outer limits of their extended continental shelf that extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State is motivated by considerations other than a sense of legal obligation, in particular a desire to avoid the possibility of their submission giving rise to a dispute with the result that the Commission would not consider it. Nicaragua also refers to certain examples of States which have made submissions to the CLCS that included the extension of their continental shelf within 200 nautical miles of another State, and notes that this practice supports the argument that the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles may extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of a neighbouring State.

58. Nicaragua also refers to the two cases concerning delimitation in the Bay of Bengal: Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Bay of Bengal (Bangladesh/Myanmar), Judgment, ITLOS Reports 2012, pp. 64-68, paras. 225-240, and Bay of Bengal Maritime Boundary Arbitration (Bangladesh v. India), Award of 7 July 2014, United Nations, Reports of International Arbitral Awards (RIAA), Vol. XXXII, pp. 104-106, paras. 336-346 (hereinafter the “Bay of Bengal cases”). According to Nicaragua, the decisions in these two cases mean that, when a State's continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from its baselines extends within the exclusive economic zone of another State, this gives rise to a “grey area” in which the two States must co-operate. It follows, in Nicaragua's view, that there is no rule of customary international law extinguishing the entitlement of one State to an extended continental shelf that overlaps with another State's entitlement to a continental shelf within 200 nautical miles from the latter's baselines.

59. Nicaragua contends that there can be no difference in law between a State's entitlement to a continental shelf based on the natural prolongation criterion and one founded on the distance criterion. Nicaragua argues that there is a single continental shelf within and beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines of the coastal State and that the same legal régime applies to all of it. While recognizing that States parties to UNCLOS are obligated to make contributions in return for the exploitation of the non-living resources of their continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles, Nicaragua argues that the juridical nature of the rights of the coastal State is the same throughout its entire continental shelf. It adds that the unity of the continental shelf was confirmed in the 2006 arbitral award in the Barbados v. Trinidad and Tobago case (Award of 11 April 2006, RIAA, Vol. XXVII, pp. 208–209, para. 213), the decision of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in the case between Bangladesh and Myanmar (Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Bay of Bengal (Bangladesh/Myanmar), Judgment, ITLOS Reports 2012, pp. 96–97, paras. 361–362) and the decision of the Special Chamber of ITLOS in Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Atlantic Ocean (Ghana/Côte d'Ivoire) (Judgment, ITLOS Reports 2017, p. 136, para. 490, and p. 142, para. 526).

60. According to Nicaragua, natural prolongation is the source of the coastal State's legal title both within and beyond 200 nautical miles. It considers that no “distance” criterion has been introduced to limit the scope of continental shelf claims, except in the provisions of UNCLOS concerning the determination of the outer edge of the continental margin, and that such is the situation at present. Recalling the historical origins of the concept of the continental shelf, Nicaragua asserts that, in the North Sea Continental Shelf cases, the Court confirmed that every coastal State has sovereign rights over the exploitable natural resources of the sea-bed that constitutes a natural prolongation of its land territory into and under the sea, with no “distance” criterion to be applied.

*

61. Colombia, for its part, considers that the continental shelf of a State beyond 200 nautical miles may not extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State.

62. Colombia argues that Article 56, paragraph 3, in Part V of UNCLOS, which concerns the exclusive economic zone, provides that the rights with respect to the sea-bed and its subsoil are to be exercised in accordance with Part VI of the Convention, which concerns the continental shelf, and that the rules of Part VI are thus incorporated by reference into the legal régime that governs the exclusive economic zone.

63. The Respondent asserts that the delimitation Nicaragua seeks would entail the vertical superimposition of two distinct national jurisdictions for distinct layers of the sea. According to Colombia, Nicaragua's claim in this case bears no relation to the “grey areas” created in the delimitation decisions in the Bay of Bengal cases. Colombia argues that such grey areas are a by-product of the adjustment made to the equidistance line in plotting the single maritime boundary between two States with adjacent coasts. It adds that the existence of a grey area cannot be upheld in this case without calling into question the very notion of the exclusive economic zone, which, it claims, was meant to join all the physical layers of the sea under one national jurisdiction in which the coastal State would exercise sovereign rights over both the living and non-living resources. Colombia concludes on this matter that the two Bay of Bengal decisions are irrelevant in this case, since those proceedings did not involve a delimitation between the 200-nautical-mile entitlement of one State and the extended continental shelf claim of another.

64. Colombia emphasizes that the legal régime that governs the exclusive economic zone is the result of a compromise reached at the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, taking into account the proposals made by a number of Latin American and African countries regarding the creation of a new sui generis 200-nautical-mile zone. In this zone, which was to have a “specific legal regime” and that would be neither territorial sea nor high seas, the coastal State would have exclusive sovereign rights over all the living and non-living resources of the water column, the sea-bed and the subsoil. The Respondent thus contends that an exclusive economic zone the water column of which is divorced from the sea-bed and subsoil is no longer an exclusive economic zone.

65. With regard to the continental shelf, Colombia recalls that, within 200 nautical miles, legal title depends on distance and that geology and geomorphology are not pertinent in this regard. While recognizing that the substantive content of the institution of the continental shelf is generally the same within and beyond 200 nautical miles from a State's baselines, Colombia maintains that the idea of the single continental shelf put forward by Nicaragua is irrelevant because the rules to be followed in determining a coastal State's entitlement to a continental shelf are different depending on whether the area in question is within or beyond 200 nautical miles.

66. According to Colombia, the package deal reflected in UNCLOS results from the negotiators' concerns about defining the outer limits of the continental margin in relation to the international sea-bed area (hereinafter the “Area”), considered the common heritage of mankind. In its view, this is confirmed by the obligation incumbent on the coastal State to make certain payments and contributions in respect of minerals taken from the area beyond 200 nautical miles.

67. According to the Respondent, in certain circumstances, State practice may be evidence of opinio juris and an examination of the extended continental shelf submissions filed by States with the CLCS clearly shows that the vast majority of those States do not claim a continental shelf that would encroach on maritime areas within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State. Colombia adds that the great majority of delimitations by way of agreement between States have disregarded geological and geomorphological features within 200 nautical miles of any coast.

* *

68. In support of their respective positions, the Parties have set out their views both on the relationship between the régime governing the exclusive economic zone and that governing the continental shelf and on certain considerations relevant to the régime governing the extended continental shelf. The Court considers each of these in turn.

69. The Court recalls that the régime that governs the exclusive economic zone set out in UNCLOS is the result of a compromise reached at the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea. Notably, this régime confers exclusively on the coastal State the sovereign rights of exploration, exploitation, conservation and management of natural resources within 200 nautical miles of its coast, while specifying certain duties on the part of the coastal State (Article 56), as well as the rights and duties of other States in that zone (Article 58). The Court has stated that the rights and duties of coastal States and other States in the exclusive economic zone set out in Articles 56, 58, 61, 62 and 73 of UNCLOS reflect customary international law (Alleged Violations of Sovereign Rights and Maritime Spaces in the Caribbean Sea (Nicaragua v. Colombia), Judgment of 21 April 2022, para. 57).

70. As stated above (see paragraph 49), the legal régimes governing the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf of the coastal State within 200 nautical miles from its baselines are interrelated. Indeed, within the exclusive economic zone, the rights with respect to the sea-bed and subsoil are to be exercised in accordance with the legal régime that governs the continental shelf (UNCLOS, Article 56, paragraph 3) and the coastal State exercises sovereign rights over the continental shelf for the purpose of exploring it and exploiting its natural resources (UNCLOS, Article 77, paragraphs 1 and 2). The Court stated in its 1985 Judgment in the Continental Shelf (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya/Malta) case that

“[a]lthough the institutions of the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zone are different and distinct, the rights which the exclusive economic zone entails over the sea-bed of the zone are defined by reference to the régime laid down for the continental shelf. Although there can be a continental shelf where there is no exclusive economic zone, there cannot be an exclusive economic zone without a corresponding continental shelf.” (Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1985, p. 33, para. 34.)

71. As regards the Bay of Bengal cases, the Court recalls that, in the case between Bangladesh and Myanmar, ITLOS delimited the 200-nautical-mile zones of two adjacent States by constructing a provisional equistance line, which it then adjusted. The Tribunal determined that both parties had entitlements to an extended continental shelf and it continued the course of the adjusted equidistance line beyond the 200-nautical-mile limit of Bangladesh (Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Bay of Bengal (Bangladesh/Myanmar), Judgment, ITLOS Reports 2012, p. 118, paras. 460-462). The use of an adjusted equidistance line produced a wedge-shaped area of limited size located within 200 nautical miles of the coast of Myanmar but on the Bangladesh side of the line delimiting the parties' continental shelves. As the Tribunal noted, this “grey area ar[ose] as a consequence of delimitation” (ibid., pp. 119-120, paras. 463 and 472). Likewise, in the case between Bangladesh and India, the arbitral tribunal found both parties to have entitlements to an extended continental shelf and followed an adjusted equidistance methodology, which produced a “grey area” of limited size lying within the extended continental shelf of Bangladesh and the 200-nautical-mile zone of India (Bay of Bengal Maritime Boundary Arbitration between Bangladesh and India, Award of 7 July 2014, RIAA, Vol. XXXII, p. 147, para. 498). Each tribunal specified that, within the “grey area”, the maritime boundary determined the rights that the parties had over the continental shelf pursuant to Article 77 of UNCLOS, but did not otherwise limit the rights of Myanmar and India, respectively, to the exclusive economic zone, as set out in Article 56 of UNCLOS, notably those with respect to the superjacent water column. Both tribunals underlined that it was for the parties to take measures they considered appropriate with regard to the maritime areas in which they had shared rights, including through the conclusion of further agreements or the creation of a co-operative arrangement (ibid., pp. 148-149, paras. 505 and 507-508; Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Bay of Bengal (Bangladesh/Myanmar), Judgment, ITLOS Reports 2012, p. 121, paras. 474-476).

72. In the two Bay of Bengal cases, the use of an adjusted equidistance line in a delimitation between adjacent States gave rise to a “grey area” as an incidental result of that adjustment. The circumstances in those cases are distinct from the situation in the present case, in which one State claims an extended continental shelf that lies within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of one or more other States. The Court considers that the aforementioned decisions are of no assistance in answering the first question posed in the present case.