Introduction

Across over 20,000 U.S. municipalities—geographically delineated by the Census Bureau as places, local governments use a wide range of policy levers to shape where people live. For example, practices such as restrictive density zoning and the spatially targeted construction of affordable housing contribute to differential sorting of racial groups across neighborhoods within places (Lens Reference Lens2022; Massey et al., Reference Massey, Rothwell and Domina2009; Owens Reference Owens2019; Rugh and Massey, Reference Rugh and Massey2014), and many of these policies also contribute to growing between-place segregation by influencing the overall racial composition across different places in the United States (LaBriola Reference LaBriola2022; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi and Taquino2015; Rothwell and Massey, Reference Rothwell and Massey2009; Shlay and Rossi, Reference Shlay and Rossi1981; Trounstine Reference Trounstine2018). In this paper, I argue that how municipalities manipulate their boundaries through annexations is one such practice that should be scrutinized because of the ways that boundaries influence racial composition, which may contribute to between-place segregation and underrepresentation of minority racial groups in municipal elections (Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi and Taquino2015).

Municipal annexations can exclude Black and Hispanic residents at the municipal fringe by avoiding annexation into those territories, also known as municipal underbounding (Aiken Reference Aiken1987; Durst Reference Durst2014, Reference Durst2019; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Parnell, Joyner, Christman and Marsh2004; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi, Grice and Taquino2007; Moeser and Dennis, Reference Moeser and Dennis2020; Mukhija and Mason, Reference Mukhija and Mason2013; Murphy Reference Murphy1978). Most research on municipal annexation has focused on the practice of municipal underbounding because of its serious implications for quality of life for excluded Black and Hispanic residents. However, municipal annexations also have important consequences for racial minority residents residing within the municipality. If annexed territory has a higher White composition than the municipality, the annexation of that territory dilutes minority political power in municipal elections (Gomillion v. Lightfoot 1960; Moeser and Dennis, Reference Moeser and Dennis2020; Murphy Reference Murphy1978; Richmond v. U.S. 1975).

Until the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder, minority-diluting annexations were theoretically subject to federal oversight for certain jurisdictions that met criteria, in accordance with Sections 4 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). Under Section 5, jurisdictions that met Section 4’s criteria—those with a history of racial discrimination in voting—are “covered” by Section 5 and must submit changes to electoral arrangements, including changes to electoral district boundaries through municipal annexations, to the Department of Justice for preclearance before they can be put in place. Jurisdictions had burden of proof to demonstrate that their proposed changes would not harm minority voters before the change can be approved. However, evidence is scarce on the extent to which minority dilution occurs through municipal annexation across the country, or whether minority dilution through annexations were exacerbated when the preclearance regime was rendered unenforceable on June 25, 2013, by the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder.

In this paper, I analyze Census shapefiles and demographic data for over 15,000 municipalities between 2007 and 2020, covering all forty states that have annexable land, to investigate whether the Shelby County ruling is associated with an increase in minority-diluting annexations.Footnote 1 Using difference-in-differences regression models, I examine whether municipalities that were previously subject to oversight are more likely to conduct annexations in general and annexations that reduce racial minority composition after Shelby County, compared to municipalities that were not subject to the preclearance regime. I find no evidence that ending federal oversight of municipal annexations resulted in Section 5 municipalities annexing more compared to municipalities not covered by Section 5—at least not in the six years after Shelby County. I also find no evidence that ending federal oversight of municipal annexations resulted in Section 5 municipalities more frequently annexing in patterns that decrease Black and non-Black minority population composition. However, these findings should not be taken as evidence that Sections 4 and 5 were no longer necessary: descriptive evidence shows that pre-Shelby County, Black and non-Black minority-diluting annexations nevertheless occurred in covered municipalities.

These findings complicate our understandings of the VRA’s effectiveness at promoting minority civil rights because this descriptive evidence suggests that Sections 4 and 5 were ineffective at preventing minority-diluting municipal annexations from occurring even when the preclearance regime was in place. One explanation for these unexpected findings is that voter suppression tactics may be complementary: since practices like enforcing strict voter ID and last-minute polling place changes are no longer subject to scrutiny under Sections 4 and 5, annexations are no longer needed as a tool of minority voter suppression. These findings have important implications for future policies modeled after the preclearance regime in the pre-Shelby County VRA. This study contributes to research on administrative boundaries as a source of racial inequality, the limitations of regulations in preventing racial exclusion, and highlights a need to better understand the Black/non-Black racial boundary in voter suppression.

Background

Federal Oversight Through Section 5 Preclearance

In 1965, Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act (VRA) to guarantee citizens’ rights to free and fair elections without racial discrimination.Footnote 2 Some scholarship hails the VRA as the most important and most successful of the civil rights laws from the 1960s for its effects on increasing overall representation of minority political interests at all levels of government (Issacharoff Reference Issacharoff2013; Sass and Mehay, Reference Sass and Mehay1995; Schuit and Rogowski, Reference Schuit and Rogowski2017; Shah et al., Reference Shah, Marschall and Anirudh2013). Under Section 5 of the VRA, jurisdictions subject to the preclearance requirement had burden of proof to show in federal court that any proposed changes to electoral arrangements would not result in disparate racial impact on political representation and must obtain federal approval for these proposed changes.Footnote 3 Section 4(b) outlined a formula for determining which jurisdictions met the criteria for coverage (hereafter “Section 5”/“covered” jurisdictions), using a combination of historical voter registration statistics and a demonstrated history of using racist voter suppression techniques like poll taxes and literacy tests.Footnote 4 Coverage varied both across and within states. Eight states in the South were covered entirely, a few states had only some counties covered, and a few counties in other states were at one time covered but later bailed out (released from oversight) after judicial review.Footnote 5 Municipal annexations were subject to the preclearance requirement under Section 5 because they could result in minority population dilution and threaten minority citizens’ right to fair representation of their political interests in municipal elections (Baumle et al., Reference Baumle, Fossett and Waren2008; Berri Reference Berri1989; Motomura Reference Motomura1982). Between the VRA’s enactment in 1965 to Shelby County in 2013, over 112,000 proposed municipal annexations were submitted to the Department of Justice seeking preclearance, by far the most prevalent form of municipal boundary changes submitted for consideration compared to municipal incorporation or consolidation.Footnote 6

On June 25, 2013, the coverage formula used in Section 4 was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder, thereby rendering the preclearance requirement in Section 5 unenforceable. Jurisdictions that had previously been subjected to the preclearance rule in Section 5 (hereafter “previously covered” jurisdictions) no longer need to submit preclearance requests prior to changing elections-related laws.Footnote 7 On the same day immediately after the decision was announced, multiple previously covered jurisdictions enacted voter ID laws that had previously been rejected at Section 5 hearings for having a racially disparate effect (Hardy Reference Hardy2020; Herron and Smith, Reference Herron and Smith2015). Many scholars and activists expected that the removal of Sections 4 and 5 would result in drastic erosion of minority voting rights (see, e.g., amicus briefs filed in support of defendant, Shelby County v. Holder 2013).Footnote 8

On the one hand, removing a regulation against racial discrimination would plausibly result in increases in racial discrimination. Sean F. Reardon and colleagues (Reference Reardon, Grewal, Kalogrides and Greenberg2012) find that schools previously subject to court-mandated desegregation orders resegregated after the mandates ended, albeit at a slower pace than expected. Specific to the VRA, case studies show that minority voter suppression laws like strict voter ID and registered voter purges increased significantly after Shelby County in previously covered jurisdictions (Feder and Miller, Reference Feder and Miller2020; Hardy Reference Hardy2020; Herron and Smith, Reference Herron and Smith2015). On the other hand, removing an ineffective law may not be associated with increases in those behaviors if the regulation never successfully deterred that behavior, as in the case of harsh policies intended to deter immigration (Cox and Goodman, Reference Cox and Goodman2018; Ryo Reference Ryo2019; Wong Reference Wong2018). A study of pre-Shelby County annexations in the Houston metropolitan area concludes that Section 5 was not effectively preventing annexations that reduce minority population shares in Houston-area municipalities (Baumle et al., Reference Baumle, Fossett and Waren2008). However, even if the law was never effective overall, its removal could still worsen already existing trends nationwide by legitimating the problematic behavior.

To adjudicate between these competing possibilities about the effects of ending Section 5 enforcement, I leverage panel data on municipalities’ annexation behavior spanning the period before and after Shelby County. Formally, I hypothesize that after invalidation by Shelby County, Section 5 municipalities are more likely to conduct annexations than non-Section 5 municipalities compared to pre-invalidation (H1). This is because Section 5 municipalities have a demonstrated history of engaging in racially discriminatory voting practices, which is what brought them under the preclearance regime to begin with, compared to the jurisdictions that did not meet criteria for federal oversight. Additionally, since annexations are no longer subject to federal oversight before they can take place, previously covered municipalities thus have more freedom to conduct annexations.

Municipal Boundaries and the Governance of Race

Even as the country becomes more racially diverse as a whole, racial diversification patterns between places remain uneven (Hall and Lee, Reference Hall and Lee2010; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi and Taquino2015). Daniel T. Lichter and colleagues (Reference Lichter, Parisi and Taquino2015) document a rise in racial segregation across places within metropolitan areas as places become more racially homogenous. In concluding, they call for more research on how “places—as political and economic actors—play a large and typically unappreciated role in excluding blacks and other minorities from the geographic mainstream” (p. 870).

Municipalities exclude Black and other non-White residents by reinforcing racial boundaries. Practices like burdensome fines and fees and increased police surveillance in minority neighborhoods can have the effect of disproportionately discouraging minority residents from living there, even if there is no expressed racist intent (Beck Reference Beck2019, Reference Beck2023; Carmichael and Kent, Reference Carmichael and Kent2014; Collins et al., Reference Collins, Stuart and Janulis2022; Harris Reference Harris2016; Muhammad Reference Muhammad2011; Pacewicz and Robinson, Reference Pacewicz and Robinson2021). Municipalities can also enforce limits on geographic boundaries that deter Black and minority population growth. For example, the proliferation of zoning laws in many municipalities is associated with growth in the number of higher income White residents while suppressing the availability of housing for lower income minority residents (LaBriola Reference LaBriola2022; Lens Reference Lens2022; Rothwell and Massey, Reference Rothwell and Massey2009; Shlay and Rossi, Reference Shlay and Rossi1981; Trounstine Reference Trounstine2018). Research from other types of administrative boundaries shows how boundaries for school districts, state legislative districts, and congressional voting district boundaries can be manipulated in ways that facilitate racial inequality, even relying on prison construction to inflate district voter counts (see, e.g., Bischoff Reference Bischoff2008; Cain and Zhang, Reference Cain and Zhang2016; Cooperstock Reference Cooperstock2023; Palandrani and Watson, Reference Palandrani and Watson2020; Reardon et al., Reference Reardon, Yun and Eitle2000; Remster and Kramer, Reference Remster and Kramer2018; Vargas et al., Reference Vargas, Cano, Del Toro and Fenaughty2021; Yarbrough Reference Yarbrough2002).

Recent research by Robert Vargas and colleagues (Reference Vargas, Cano, Del Toro and Fenaughty2021) reveals how the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Louis city councils gerrymandered their city council voting district boundaries since as early as the 1800s to maintain White political dominance over growing threats of Black political strength. Politicians in these municipalities manipulated the redistricting process to use political boundaries as “an instrument of race- and class-based social control” (Vargas et al., Reference Vargas, Cano, Del Toro and Fenaughty2021, p. 3). Their research focused on municipal redistricting of internal boundaries, whereas I argue that the boundaries of the municipality itself is also an instrument of race- and class-based social control because they are the “locality where political or economic battles are fought and where affluent or poor, White or minority, or immigrant or native groups are included or excluded from the community” (Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi and Taquino2012, p. 367).

Termed municipal underbounding, some municipalities refuse to annex neighboring territories at the fringe of the municipality with racial minority groups and instead annex majority-White neighborhoods (Aiken Reference Aiken1987; Anderson Reference Anderson2008; Durst Reference Durst2014, Reference Durst2019; Durst et al., Reference Durst, Cai, Tillison-Love, Huang and Henry2021; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Parnell, Joyner, Christman and Marsh2004; Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Parnell and Joyner2010; Mukhija and Mason, Reference Mukhija and Mason2013; Murphy Reference Murphy1978). Most of the research on municipal annexations focuses on the phenomenon of municipal underbounding by comparing the racial composition of fringe territory that was and was not annexed. Municipal underbounding can have serious consequences on the quality of life for predominantly Black and Hispanic communities relegated to the municipal fringe with worse services (Aiken Reference Aiken1987; Durst Reference Durst2014). However, municipal annexations can also have consequences for racial minority residents already living within the annexing municipality. Annexation weakens minority political power in local government if the addition of predominantly White residents through annexation dilutes their population shares (Baumle et al., Reference Baumle, Fossett and Waren2008; Moeser and Dennis, Reference Moeser and Dennis2020; Taper Reference Taper1962). If pursued in this way, municipalities can use racially selective annexations to shape their overall demographic makeup to the effect of racial and class control (Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi and Taquino2015; Vargas et al., Reference Vargas, Cano, Del Toro and Fenaughty2021), but prior research on this aspect of annexations is limited in geographic scope and has not looked at post-Shelby County changes.Footnote 9 Noah J. Durst (Reference Durst2019) finds that compared to non-Section 5 municipalities, Section 5 municipalities were more likely to underbound Black fringe territory during annexation after Shelby County, but this research does not address whether the consequences of annexations for minority populations within annexing municipalities were exacerbated. It is possible that municipalities prefer to annex territory that had a lower Black composition than other annexable territory but the annexation itself nevertheless does not affect the existing Black population share in the municipality. Hence, it is necessary not only to examine whether municipalities discriminate between annexable territory, but also to measure what the demographic consequences of annexation are for the municipality. Formally, I hypothesize that after invalidation, Section 5 municipalities will be more likely to conduct annexations that reduce their percent Black and percent non-Black minority population shares, since they are no longer subject to federal oversight prohibiting such annexations (H2).

The Changing Color Line and Black Exceptionalism

Previous research on municipal annexations has primarily investigated the avoidance of Black communities (Aiken Reference Aiken1987; Durst Reference Durst2019; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Parnell, Joyner, Christman and Marsh2004; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi, Grice and Taquino2007), with three exceptions that investigate the avoidance of Hispanic communities (Durst Reference Durst2014, Reference Durst2018; Wilson and Edwards, Reference Wilson and Edwards2014). But, as the United States continues to experience growth in racial minority populations through immigration from a diverse set of countries, municipalities are becoming even more diverse beyond Black, White, and Hispanic, with the predominant racial minority group(s) additionally varying across metropolitan areas and states (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Jones, Rabe, Pratt, Medina, Orozco and Spell2021). The theory of racial threat posits that as places become more racially diverse, White people intensify efforts to maintain their dominant group position (Blumer Reference Blumer1958; Bobo and Hutchings, Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Wilkes and Okamoto, Reference Wilkes and Okamoto2002). Other research finds that White people living in places with a decreasing White population share exhibit fear towards these demographic changes and direct this resentment towards Black groups (Abascal Reference Abascal2022; King and Wheelock, Reference King and Wheelock2007; Stacey et al., Reference Stacey, Carbone-López and Rosenfeld2011). Sections 4 and 5 were intended to protect racial minority groups in general and not only Black or Hispanic groups, but existing research on the impacts of post-Shelby County municipal annexations has not yet examined consequences for other racial minority groups.

Prior literature on Black exceptionalism suggests that trends for Black groups would be distinct from any other racial minority group. Black exceptionalism refers to the distinctly large social distance between Black versus non-Black residents compared to any other pairwise comparisons between racial groups (Parisi et al., Reference Parisi, Lichter and Taquino2011), for example the social distance between White and Asian groups are smaller compared to the social distance between White and Black groups. This bright Black/non-Black boundary is apparent in residential segregation patterns, individual preferences for neighborhoods by neighborhood racial composition, and other indicators of social closeness like interracial relationships across a variety of contexts (see Hwang and McDaniel (Reference Hwang and McDaniel2022) for a review).Footnote 10 Therefore, I expect that if municipalities discriminate and use annexations to dilute minority population shares, their annexation patterns would also reflect this bright Black/non-Black boundary and exhibit Black exceptionalism (Fox and Guglielmo, Reference Fox and Guglielmo2012; Lee and Bean, Reference Lee and Bean2004). In other words, municipalities may be more likely to pursue annexations that dilute Black population shares than to pursue annexations that dilute other non-Black minority population shares. Formally, I hypothesize that the treatment effect of Shelby County would be larger for Black-diluting annexations than for non-Black minority-diluting annexations (H3).

Data and Methods

Outcome Variables

Identifying Annexations

To address the first question of whether probabilities to annex changed after Shelby County, I use a binary indicator of conducting an annexation as the outcome variable. This is assigned 1 if the municipality conducted an annexation in a given period and 0 otherwise. Municipalities—which correspond geographically to Census places—conduct annexations. Census blocks, which nest up to Census places, are the smallest available geographic unit that can be annexed. I identify municipal annexations by comparing block- and place-level shapefiles at the beginning and end of a specified time interval (e.g., comparing 2007 to 2008 for annual intervals, comparing 2007 to 2009 for two-year intervals, or comparing 2007 to 2013 for six-year intervals), aided by spatial analysis tools in the R package ‘sf’ (Pebesma Reference Pebesma2018). As with prior approaches, I define a block as having been annexed if a block 1) exists both in the beginning and the end of the time interval; 2) was not already part of another municipality at the beginning of the time interval; and 3) was not within the boundary of a place in the beginning of the time interval but became within the boundary of a place by the end of the time interval (Durst Reference Durst2014, Reference Durst2018, Reference Durst2019; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi, Grice and Taquino2007; Wilson and Edwards, Reference Wilson and Edwards2014).Footnote 11 Annexations up to 2013 correspond to events that occurred prior to the Supreme Court decision; annexations after 2014 correspond to the period after the decision. I do not consider any annexations in 2013–2014 since the decision was in June of 2013 and shapefiles are only updated annually to January 1 of that year. Hence, the last available pre-Shelby County municipal boundaries are as of January 1, 2013 and the first post-Shelby County municipal boundaries are as of January 1, 2014. If I analyze annexations between 2013–2014 using the 2013 and 2014 shapefiles, I would not be able to distinguish between annexations that occurred before and after the decision.

One significant challenge of this approach is that boundaries change between years for reasons unrelated to annexation. Refinements in how Census place boundaries are drawn over time, even when based on the same Census boundary-year, may result in boundary changes that are incorrectly recorded as annexation. Oddly shaped municipalities, such as those with “holes” within the municipality or jagged edges (see Durst et al., Reference Durst, Cai, Tillison-Love, Huang and Henry2021 for examples), are particularly sensitive to refinements in shapefile boundaries unrelated to annexation.

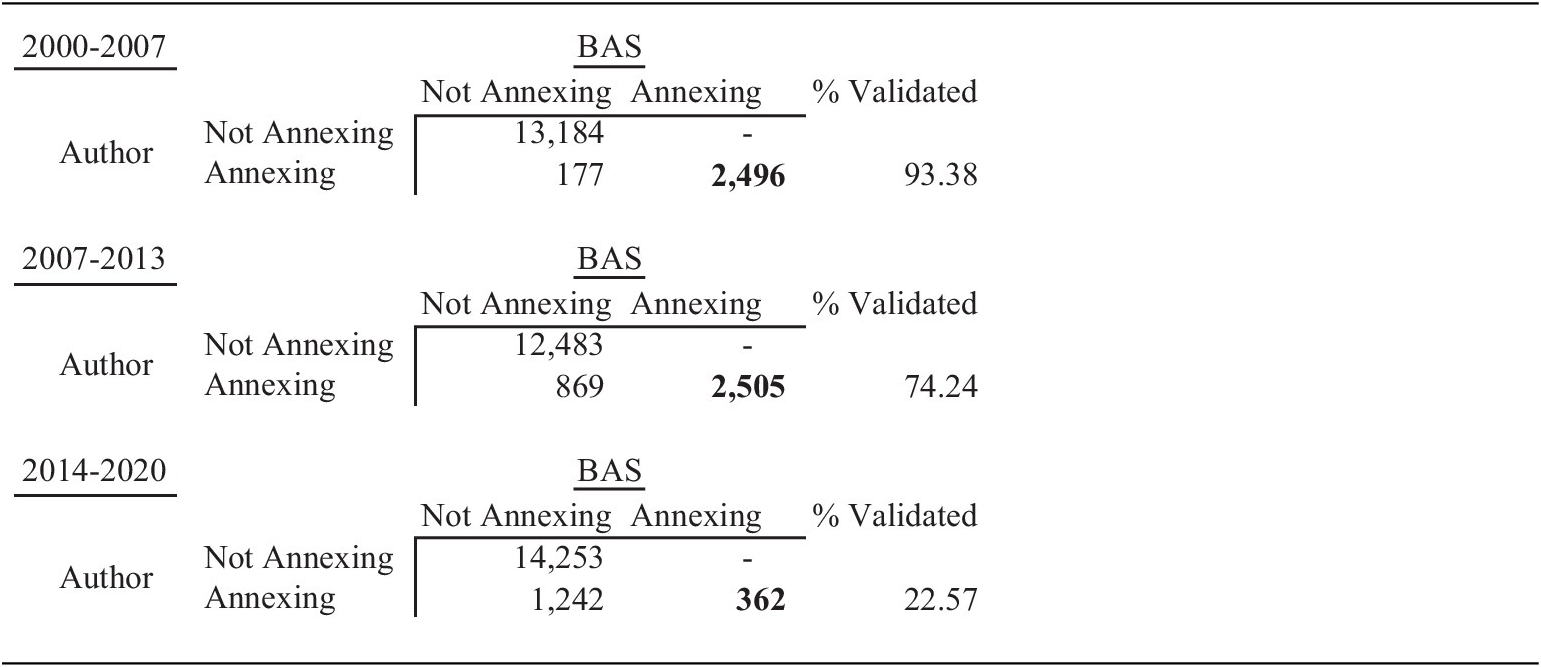

I reduce the possibility of misclassification in two main ways: First, I only classify Census blocks as being within a place if there is at least ninety percent areal overlap with the place boundaries, both at the beginning and at the end of the time interval. Thus, all annexed blocks I identified have at least ninety percent areal overlap with the annexing place’s boundaries at the end of the period. Second, I validate my identified annexations with annexations recorded in the Census Bureau’s Boundary and Annexation Survey (BAS), which is the only official source of boundary changes. Researchers do not typically rely on the BAS to identify annexations because the survey is optional, there can be extensive lag time before annexations become officially recorded in the BAS, and no geographic identifiers are provided for annexed territory, which makes it impossible to measure the demographic characteristics of annexed territory.Footnote 12 Nevertheless, I check whether a municipality I identified as having conducted an annexation during a given period is also officially recorded as having conducted an annexation in the BAS. Even though the validation rate against the BAS is low—especially for more recent annexations (see Table A1 in the Appendix), I do not miss any annexations: there are no municipalities recorded officially in the BAS as having annexed that year that I do not pick up. Relying only on the subset of observations that are validated in the BAS does not change my substantive results.Footnote 13

Annexations are identified for all states in the United States except the nine states in the Northeast, consistent with prior approaches that exclude these states due to lack of available territory for annexation (Durst Reference Durst2018, Reference Durst2019; Edwards Reference Edwards2008). Census Designated Places (CDPs) are unincorporated communities assigned place IDs by the Census but do not have conventional municipal government structures. I exclude them as places that could conduct annexations. Since all places in Hawaii are CDPs, there are no municipalities from Hawaii in my analysis, yielding coverage of forty states in total. Unincorporated Census blocks and blocks in CDPs located within a 400-meter buffer of places are candidates for annexation (Durst Reference Durst2018, Reference Durst2019).Footnote 14 Annually updated place boundaries are available beginning in 2007. While I collected data on annexations using these annual periods (e.g., 2007–2008, 2008–2009, …, 2018–2019, 2019–2020), the main analyses presented here rely on annexations identified based on comparisons of boundaries across two six-year periods that correspond to pre-Shelby County and post-Shelby County: 2007 to 2013 and 2014 to 2020. The closest pre-2007 shapefiles are from 2000, so I compare place boundaries between 2000 and 2007 (instead of 2001 to 2007) as an additional pre-Shelby County period. I present results from these wider periods because the identification of annual annexation activity is noisy with jumps and dips in activity between consecutive years (see Figure A1 in the Appendix). Additionally, the validation of my identified annexations against the BAS is substantially higher using wider periods than annual ones. However, I repeat all analyses presented here with annexations measured annually and in two-year intervals and the conclusions I draw are consistent.

In my main analysis, municipalities must have been in continued existence from 2007 to 2020 without missing data on covariates in 2007 and 2014 to ensure a balanced panel. This means that newly incorporated municipalities or those that disincorporated at any point between 2007 to 2020 are not included. Municipalities that only annexed unpopulated blocks are not considered to have annexed since the main goal of this paper is to understand annexations that involve populations. In total, my balanced panel consists of observations for 15,857 unique municipalities between 2007–2020 across forty states and 4978 annexations.

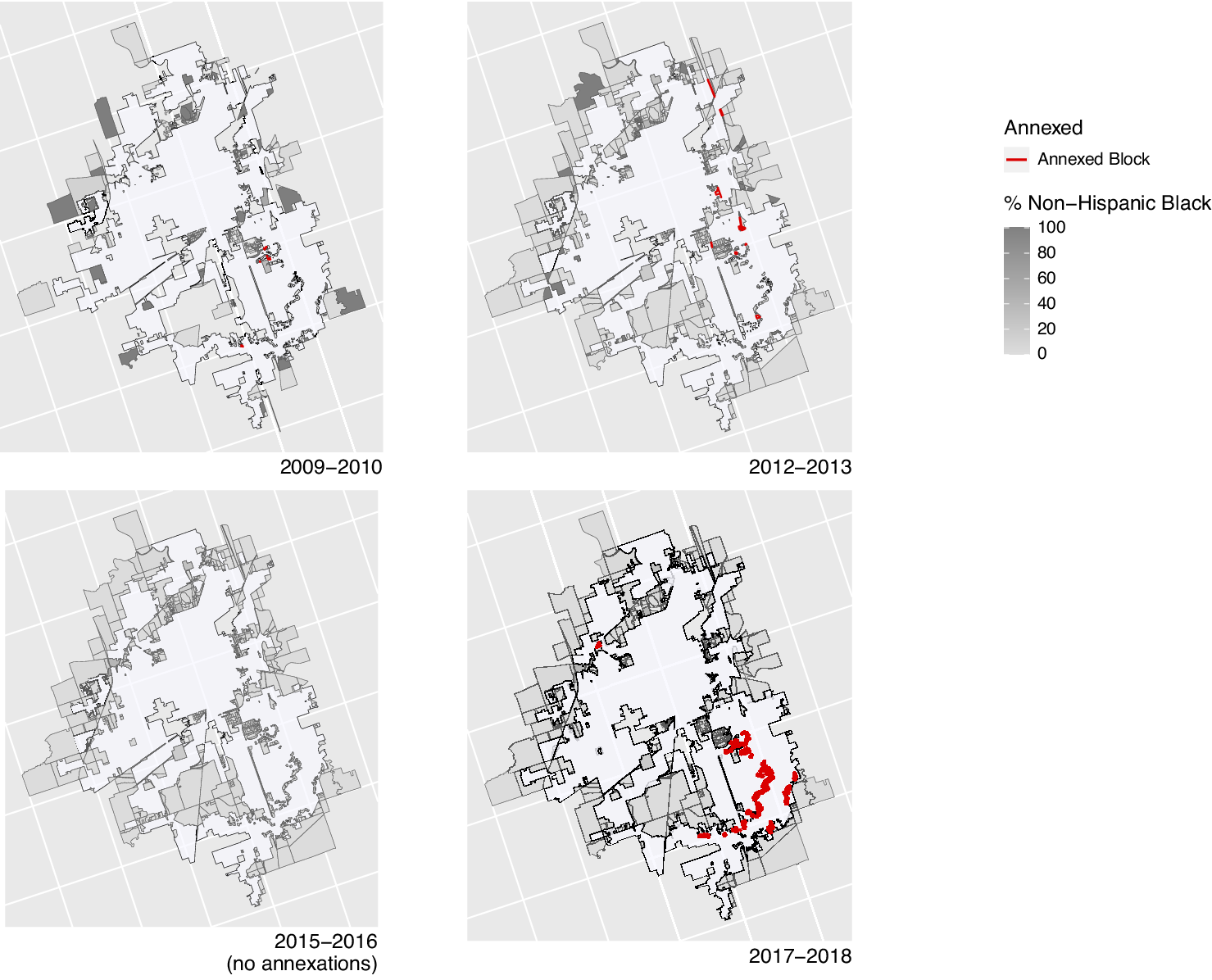

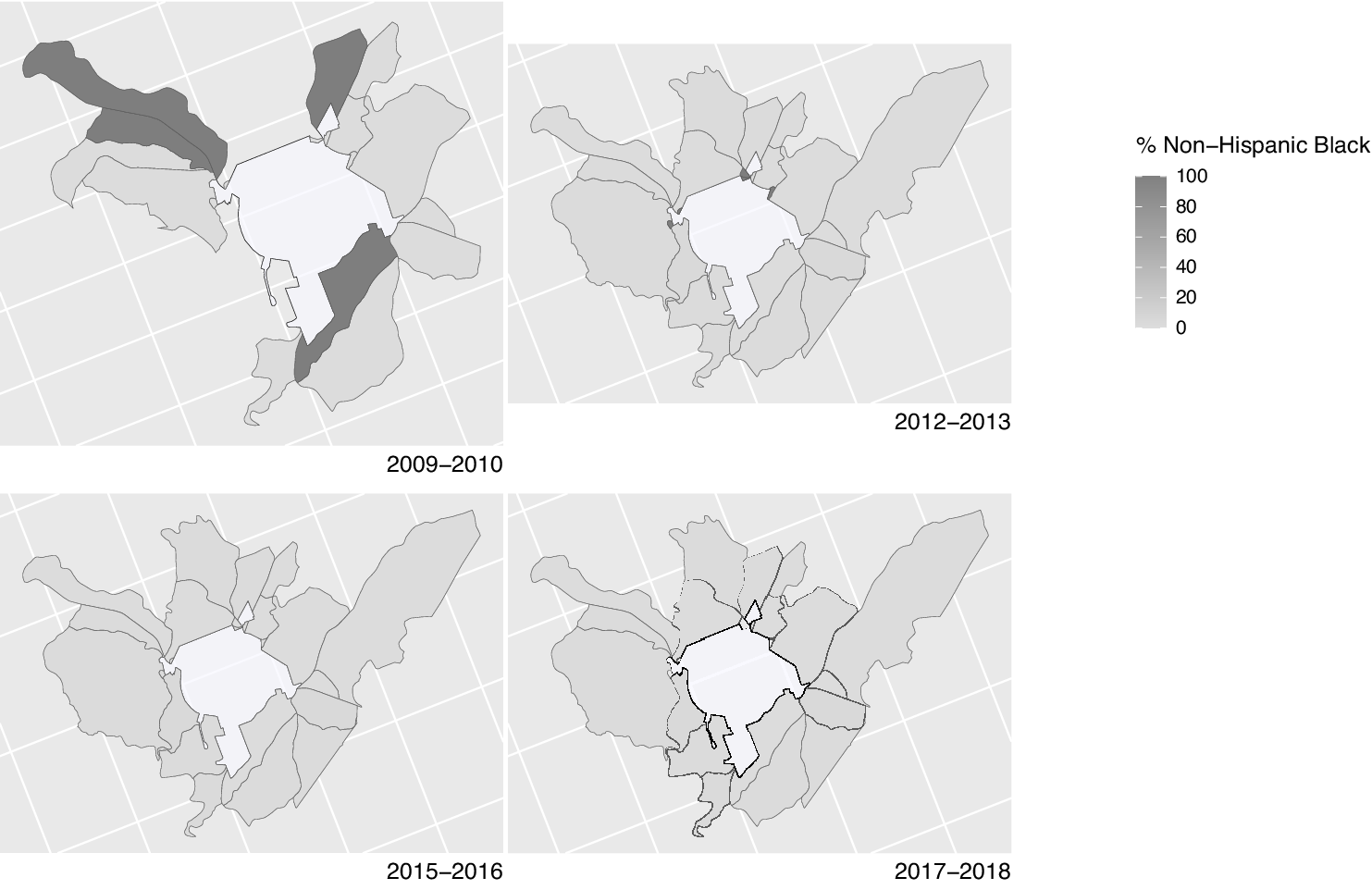

Figures 1 to 3 show municipal boundaries for Atlanta, GA, Springville, IL, and Waleska, GA, over four annual periods—two pre-Shelby County and two post-Shelby County. Blocks are shaded with a greyscale gradient corresponding to Black composition of the fringe territory. Blocks highlighted in bold red outlines are those that I identify as having been annexed during the period. These plots show that my identification strategy allows me to identify some annexations even when very few blocks are involved and even when municipal boundaries are oddly shaped.

Fig. 1. Atlanta, Georgia municipal boundaries, 2007-2020.

Fig. 2. Springfield, Illinois municipal boundaries, 2007-2020.

Fig. 3. Waleska, Georgia municipal boundaries, 2007-2020 (No Annexations).

Measuring Demographic Consequences of Annexations

Prior to Shelby County, any decrease in minority composition as a result of annexation by a Section 5 municipality required approval by a federal court through the preclearance process. To answer the second question of whether previously covered municipalities are more likely to conduct minority-diluting annexations after Shelby County, I generate a binary indicator based on a comparison of the racial composition between the municipality and annexed territory. I also use this indicator to answer the third question of whether the treatment effect is stronger for Black groups. If the annexed territory has a lower Black or non-Black minority composition than the municipality, the annexation dilutes the existing Black and non-Black minority population shares. One indicator focuses on whether the annexed territory has a lower Black composition, which takes on value 1 if the Black composition in the annexed territory is lower than that in the annexing municipality and 0 otherwise, or if the municipality did not annex during the period. I generate a similar binary indicator for assessing whether the annexed territory has a lower share of non-Black minority (i.e., Hispanic, Asian, Native, other/multi-racial composition) population than the municipality. Black composition refers to the population that is Black only (e.g., non-Hispanic Black only). The population composition variables are assessed at the baseline year. I combine all non-Black racial minority groups because the vast majority of municipalities have very small shares of non-Black and non-Hispanic racial minority groups.

Data

I use Census and American Community Survey (ACS) data to measure municipal characteristics, and Census data to measure block characteristics. Only the 5-Year place-level ACS data—as opposed to the 1-Year or 3-Year, which are limited based on population thresholds of 60,000 and 20,000 respectively—contain observations for all municipalities in the United States in each survey, regardless of population size. I use the midpoint year for the 5-Year ACS surveys: 2007 data is measured with the 2005–2009 ACS; 2014 data is measured with the 2012–2016 ACS; and 2000 data for the additional, pre-Shelby County period used in the difference-in-differences analysis is measured with the 2000 Census.

For block-level data, I use linear interpolation to generate data for 2007 and 2014 using 2000, 2010, and 2020 Census data. To harmonize 2000 and 2020 data to 2010 boundaries, I use the 2000-to-2010 and 2020-to-2010 block-to-block crosswalk files provided by the NHGIS. Unique cross-year block pairs are selected by only retaining blocks with the largest areal overlap. Blocks with missing weights, no corresponding 2010 block IDs, or missing data at either the beginning or end of the period are dropped from the analysis. Variables are then multiplied by the weights given in the crosswalk files (Manson et al., Reference Manson, Schroeder, Van Riper, Kugler and Ruggles2021).

Independent Variables

For the first question on whether the Shelby County decision is associated with changes in municipalities’ probability to conduct annexations, the independent variables are a binary indicator of Section 5 coverage and a binary indicator of being in the post-Shelby County annexation period (i.e., after 2014). Some states are covered by Section 5 entirely, whereas in others only a selection of counties is covered. If the municipality is in a fully covered state or if it is in a covered county, it is assigned 1 for the Section 5 variable throughout all periods (time-invariant). Census places—which I use to operationalize municipalities—do not have county identifiers since they can cross county lines, but Census blocks have both place and county identifiers. If any block in the municipality is within a Section 5-covered county, the municipality is assigned 1 for the coverage variable. Since I am relying on a difference-in-differences framework, described more below, I only interpret the interaction term between these two variables. If this interaction term is statistically significant, it suggests that the Shelby County decision has an associated effect on previously covered municipalities’ likelihood to conduct annexations.

In the second question, I ask whether previously covered municipalities are more likely to conduct minority-diluting annexations after the Shelby County decision. I use a similar estimator as above. If the coefficient on the interaction term is statistically significant, it suggests that Section 5 invalidation has an associated effect on the prevalence of minority-diluting annexations. In the third question, I ask whether the treatment effect is larger against Black populations compared to non-Black minority populations. I compare the estimator size among models analyzing the outcome for Black population dilution and for non-Black minority population dilution.

Control Variables

For the first outcome—probability to annex—I include controls for the municipality’s population size and population density at the baseline year (Durst Reference Durst2019; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi, Grice and Taquino2007). Racial composition of the municipality and of its annexable territory are also likely associated with the likelihood to annex. A predominantly White municipality may be less likely to annex predominantly Black blocks. I include controls for the municipality-level percent Black and percent non-Black minority (Durst Reference Durst2019; Durst et al., Reference Durst, Cai, Tillison-Love, Huang and Henry2021; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi, Grice and Taquino2007). Percent White is omitted due to collinearity. I also include controls for demographic characteristics of the annexable blocks surrounding municipalities—specifically, the percent Black and non-Black minority population (Durst Reference Durst2019; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi, Grice and Taquino2007).

Socioeconomic considerations play a role in annexation decisions (Anderson Reference Anderson2008, Reference Anderson2010), but Census block-level data are limited in socioeconomic indicators beyond housing tenure, which I already include. Areas with commercial activities that could generate high sales tax revenue and areas with potential for increasing property and income tax bases are attractive candidates for annexation (Durst Reference Durst2018, Reference Durst2019). I use the Census block-level Residential Area Characteristics (RAC) and Worker Area Characteristics (WAC) files from the Census Bureau’s LODES datasets to provide additional insight into the potential economic benefits of annexing particular blocks. Using the annual RAC files from 2007 and 2014 (on 2010 boundaries using the LODES7 dataset), I derive the percent of residents in each Census block earning at least $3,333 per month—the highest salary tier in the data. Using the WAC file for these same years, I calculate the percent of jobs in each block in the retail and manufacturing industries for each base period year. At the municipality-level, I include median home value, median household income, percent poverty, and percent owner-occupied housing units. Because socioeconomic considerations can often mask underlying racial stereotypes, I include a control for the percent Black and percent non-Black minority in poverty (Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi, Grice and Taquino2007).

A number of state-level regulations govern annexations, such as ordinances requiring petitions and public hearings (Durst Reference Durst2018). Though these laws may change over time, available data on these laws are time-invariant. Since there are no municipalities in my sample that cross multiple state lines, state-level variations in laws governing annexations are captured in municipality fixed effects.Footnote 15

For the second set of outcomes—Black-diluting and non-Black minority-diluting annexations—I include control variables for the respective composition (i.e., percent Black; percent non-Black minority) in the municipality and among annexable blocks. For instance, it may not be possible for a municipality to avoid conducting a Black-diluting annexation if all annexable fringe territory has a higher White composition. In all models, I use municipality fixed-effects to account for unobserved, time-invariant municipality-level variation influencing likelihood to annex, such as local regulations that affect how easy or hard it is to conduct annexations, community appetite for annexations, taste for discrimination, and so on.

Analytic Strategy

To model the probability of annexation using this panel data, I use a two-group and two-period difference-in-differences model. I use an interaction term between the binary variables for Section 5 coverage and being in the post-Shelby County period. This interaction term is used to assess whether the Shelby County decision is associated with an increase in the probability of a previously covered municipality to conduct an annexation. Interaction terms in a logistic model are not easily interpretable (Ai and Norton, Reference Ai and Norton2003) and its use in a difference-in-differences set-up that relies on the interaction term is challenging and not recommended without further restrictions to the data (Athey and Imbens, Reference Athey and Imbens2006; Karaca-Mandic et al., Reference Karaca-Mandic, Norton and Dowd2012). To facilitate a more straightforward analysis of the coefficient, I use a linear probability model regressing annexation on the difference-in-differences estimator:

Where

![]() $ {Annex}_i $

is a binary indicator assigned 1 if a municipality i conducted an annexation within the period and 0 otherwise. Section 5 is a binary indicator assigned 1 if municipality i is covered by Section 5 and 0 otherwise. Post-Shelby County is assigned 0 if the period is prior to 2013, and 1 if the period is in 2014 or after. Xi is a matrix of time-varying covariates for municipality i, The use of time-varying covariates is contentious in difference-in-differences estimation, especially if the treatment influences the covariate in the next period (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2009; Caetano et al., Reference Caetano, Callaway, Payne and Rodrigues2022; Gelman and Hill, Reference Gelman and Hill2007). This source of confounding is especially plausible here. Prior research suggests that, for example, the socioeconomic status of Black residents in Section 5 jurisdictions declined after the decision (Aneja and Avenancio-León, Reference Aneja and Avenancio-León2019), which may then affect the relationship between Black population composition and the likelihood of annexations, and also the effect of annexations on Black population composition. The use of lagged variables is also not advised with panel data (Allison et al., Reference Allison, Williams and Moral-Benito2017). Following the approach taken in recent work to address these sources of potential bias in modeling choices, I estimate models both with and without these time-varying covariates and use unit-clustered (municipality) robust standard errors (Faber Reference Faber2020; Torche and Rauf, Reference Torche and Rauf2021). In all models, I additionally cluster standard errors at the state-level because the treatment status of each municipality is not independently assigned. It depends on their county or their state. I do not use county for clustering because the Census Bureau does not assign county identifiers to municipalities since municipalities can cross county boundaries.

$ {Annex}_i $

is a binary indicator assigned 1 if a municipality i conducted an annexation within the period and 0 otherwise. Section 5 is a binary indicator assigned 1 if municipality i is covered by Section 5 and 0 otherwise. Post-Shelby County is assigned 0 if the period is prior to 2013, and 1 if the period is in 2014 or after. Xi is a matrix of time-varying covariates for municipality i, The use of time-varying covariates is contentious in difference-in-differences estimation, especially if the treatment influences the covariate in the next period (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2009; Caetano et al., Reference Caetano, Callaway, Payne and Rodrigues2022; Gelman and Hill, Reference Gelman and Hill2007). This source of confounding is especially plausible here. Prior research suggests that, for example, the socioeconomic status of Black residents in Section 5 jurisdictions declined after the decision (Aneja and Avenancio-León, Reference Aneja and Avenancio-León2019), which may then affect the relationship between Black population composition and the likelihood of annexations, and also the effect of annexations on Black population composition. The use of lagged variables is also not advised with panel data (Allison et al., Reference Allison, Williams and Moral-Benito2017). Following the approach taken in recent work to address these sources of potential bias in modeling choices, I estimate models both with and without these time-varying covariates and use unit-clustered (municipality) robust standard errors (Faber Reference Faber2020; Torche and Rauf, Reference Torche and Rauf2021). In all models, I additionally cluster standard errors at the state-level because the treatment status of each municipality is not independently assigned. It depends on their county or their state. I do not use county for clustering because the Census Bureau does not assign county identifiers to municipalities since municipalities can cross county boundaries.

For question 2, to understand whether the Shelby County decision increased the prevalence of annexations that alter a municipality’s racial composition, I use a similar difference-in-differences model as above:

Where r refers to the racial composition outcomes for Black, and non-Black minority for municipality i. Lower racial composition is a binary indicator assigned 1 if the racial composition of annexed territory is less than in the annexing municipality. As with model 1, I also compare models with and without time-varying covariates and I cluster standard errors at the state-level. For question 3, to compare the treatment effects for Black and non-Black minority groups, I compare the difference-in-differences estimator across the two outcomes.

The advantage of the difference-in-differences model is that the use of unit and time fixed effects allows me to use each municipality as its own control over time, thus “differencing out” the contributions of unobservable municipality- and time-specific factors to the outcome. However, I do not interpret results here with causality as the two key assumptions for the difference-in-differences model to produce causal estimates are not perfectly met (Wing et al., Reference Wing, Simon and Bello-Gomez2018). The difference in outcomes between covered and not covered municipalities prior to Shelby County does not appear to be strictly parallel using a visual test, whether assessing annual, two-year, or six-year intervals (Figure 4 and Figure A1). While the overall trends between covered and not covered municipalities roughly mirror each other, the gap widens and narrows at different times and does not remain strictly parallel. Plotting trends conditional on key covariates such as municipal population density, White composition, and population size of annexable territory does not improve pre-treatment parallel trends.

Fig. 4. Pre- and post-Shelby County trends in annexation activity, by type.

Furthermore, an important second assumption is that there is no treatment anticipation such that treatment is strictly exogenous (Wing et al., Reference Wing, Simon and Bello-Gomez2018). If municipalities ramped up or ramped down annexation activity in anticipation of the Shelby County outcome, this would violate the strict exogeneity assumption. Anticipation is plausible since the lawsuit leading to the Shelby County v. Holder decision began in 2010, in part because Shelby County wanted to challenge a DOJ objection to the results of an election after 177 municipal annexations in the City of Calera, AL, none of which were ever precleared (Shelby County v. Holder 2011). Figure 4 shows that there was a spike in general annexation and Black-diluting annexation activity pre-Shelby County, from 2000–2007 to 2007–2013.

I take advantage of more fine-grained annual interval data to perform multiple sets of sensitivity analyses to check the extent to which my results are robust to violations of these two key assumptions underpinning the difference-in-differences model. First, Ashesh Rambachan and Jonathan Roth (Reference Rambachan and Roth2023) recommend a sensitivity analysis that allows for violations of the parallel trends assumption pre-treatment. In this approach, given an amount of slope deviation from parallel trends in the pre-treatment periods, one can set a restriction that the reported treatment effect may not deviate from the counterfactual linear trend by that same amount. A deviation (the reported treatment effect) that is greater would be considered sensitive to a violation of parallel trends by that amount. Using the R package ‘HonestDiD’ created by the authors, I generate sets of confidence intervals corresponding to varying magnitudes of these violations of parallel pre-trends to test whether the treatment effect is still statistically significant at various magnitudes of slope deviation. In other words, how severe would the violation of the parallel trends assumption need to be in order to invalidate the reported treatment effect?

In addition to this analysis, I perform a falsification test to address potential violations of the no-anticipation assumption. Since treatment occurred in 2014, there should not be a treatment effect if the treatment year were artificially set to another year pre-treatment (Lechner Reference Lechner2011). In this test, I drop observations after 2014 and set 2010 as the artificial, placebo treatment year. Using annual periods (e.g., 2007–2008, 2008–2009), I code annexations from 2007–2008 and 2008–2009 as pre-treatment and annexations from 2010–2011 and 2011–2012 as post-treatment. Using an event study regression, I ascertain whether there is an artificial treatment effect for 2010–2011 and 2011–2012. Third, in the event that the pre-trends for control cases differ too substantially from those for treated cases to be used as controls, I test results from an alternative model. I drop control cases altogether and only compare outcomes for covered municipalities pre- and post-Shelby County to assess whether these outcomes were more likely to occur for covered municipalities after Shelby County. My conclusions drawn are robust to these three sets of sensitivity analyses. All underlying data and replication code for main and supplementary analyses are publicly available on the project repository for the article.Footnote 16

DESCRIPTIVE RESULTS

Table 1 below compares the differences between covered and not covered municipalities pre-Shelby County and post-Shelby County for the three outcomes—annexing, annexing territory with lower Black composition, and annexing territory with lower non-Black minority composition. I also compare characteristics of the municipalities themselves and of annexable territory. Statistical significance for the differences between covered and not covered municipalities is calculated based on a two-sample t-test. Table 1 shows a few important trends: first, prior to Shelby County, in the 2007–2013 period, a larger proportion of covered municipalities conducted any annexations (around 5% more) and annexations of territory with lower Black composition (around 3% more) than not covered municipalities. After Shelby County, these differences are smaller in magnitude, but still a larger proportion of covered municipalities conduct any annexations (2.7% more) and annexations of territory with lower Black composition (around 2% more) than not covered municipalities. If Sections 4 and 5 were working as intended, it is unexpected that covered municipalities were more likely to annex and to annex territory with lower Black composition than not covered municipalities pre-Shelby County. The difference in the proportion of municipalities that conduct annexations of territory with lower non-Black minority composition is not statistically significant in either period. Moreover, in both periods and across municipalities, non-Black minority-diluting annexations are more frequent than Black-diluting annexations. This trend is contrary to what is expected under the Black exceptionalism hypothesis, which posits that Black-diluting annexations would be more frequent. Finally, among municipalities that annexed, covered municipalities on average annexed territory with more population and larger area than not covered municipalities, which suggests that covered municipalities pursue annexations for different reasons (e.g., to grow in population size and land area) than not covered municipalities or that the characteristics of annexations by covered municipalities differ from annexations by uncovered municipalities. However, these differences do narrow over time.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for analytical sample

Notes: *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; two-tailed tests; $ values adjusted to 2020 amounts.

Covered and not covered municipalities differ significantly on many demographic characteristics that may explain these differences in annexation patterns, which supports the inclusion of these covariates in my difference-in-differences models. For example, covered municipalities are significantly more racially diverse and are less socioeconomically advantaged. Characteristics of fringe territory of covered and not covered municipalities differ significantly as well. A significantly higher proportion of covered municipalities are surrounded by territory that is more White than the municipality, but annexable territory to covered municipalities is nevertheless more racially diverse compared to annexable territory to not covered municipalities.

RESULTS

Figure 5 plots the difference-in-difference coefficients from linear probability regression models for all three outcomes—annexations, Black-diluting annexations, and non-Black minority-diluting annexations. Coefficients for the baseline model without time-varying covariates are plotted in circles next to coefficients for the full model with covariates in triangles. Results do not differ substantially between the baseline model and the full model for all three outcomes, and an ANOVA test shows that the addition of covariates does not significantly improve variance explained by the models. Standard errors are clustered by municipality and state across both models.

Fig. 5. Difference-in-differences coefficients by outcome.

On the leftmost side of the figure, coefficients for the annexation outcome are plotted. Consistent with descriptive results, there is no evidence of a statistically significant positive treatment effect in the years after Shelby County. That is, the removal of the preclearance requirement in Shelby County is not associated with a significant jump in annexations among previously covered municipalities. Contrary to expected, I fail to reject the null hypothesis for H1. Overall, there is no evidence to conclude that Shelby County encouraged previously covered municipalities to conduct more annexations, at least not within the first six years after the decision.

Racial Composition by Section 5 Coverage and Shelby County

Next, I turn to analyzing what the consequences of annexations are. Even though annexations decreased in frequency after Shelby County, municipalities that conduct annexations may still do so in ways that dilute existing Black and non-Black minority population shares more than compared to prior to Shelby County. I hypothesized that after Shelby County, Section 5 municipalities will conduct more annexations where the annexed territory has a lower Black and non-Black minority composition than in the annexing municipalities (H2). I also hypothesized that the effect will be larger for Black compared to non-Black minority populations (H3).

In the middle of Figure 5, difference-in-differences coefficients for Black-diluting annexations are plotted. Contrary to expectations, the coefficients suggest that Shelby County had a statistically significantly negative treatment effect. That is, invalidation of Sections 4 and 5 reduced these sorts of annexations. However, statistical significance is not robust to the sensitivity analysis suggested by Rambachan and Roth (Reference Rambachan and Roth2023) at even very small magnitudes of potential deviation from parallel pre-trends. Hence, I do not conclude that Shelby County caused previously covered municipalities to reduce Black-diluting annexations. Nevertheless, I have insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis in H2. That is, there is no evidence that Black-diluting annexations increased significantly in previously covered municipalities.

On the rightmost side of Figure 5, difference-in-differences coefficients for non-Black minority-diluting annexations are plotted. There is no evidence of a statistically significant positive treatment effect in the years after Shelby County: the removal of the preclearance requirement in Shelby County is not associated with a significant jump in non-Black minority-diluting annexations among previously covered municipalities. Given that neither set of coefficients is statistically significant for Black-diluting and non-Black minority-diluting annexations, I have insufficient evidence to reject the null in H3. I find no evidence that Shelby County exacerbated the use of municipal annexations to dilute Black populations in previously covered municipalities to a more severe extent than for non-Black minority populations.

Taken together, results from all three models are contrary to expectations. They do not align with expectations that Shelby County would result in increased annexation activity in general (H1), and in increased annexations that dilute Black populations (H2) that highlight a bright Black/non-Black boundary (H3). These conclusions are robust to alternative specifications of annexation based on validation against the BAS, to generalized difference-in-difference models using annual and two-year intervals (event study regressions), and to sensitivity analyses addressing violations of assumptions underlying the two-period, two-group difference-in-differences model.Footnote 17

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Shelby County v. Holder removed a crucial protection against minority voter suppression by releasing Section 5 jurisdictions from seeking federal oversight prior to enacting voting law changes. Despite the widespread belief among legal scholars and activists that Shelby County would exacerbate minority voter suppression practices among previously covered jurisdictions, little is known about the extent to which these predictions came true in the case of a specific practice: minority population dilution through changing municipal boundaries. This is partly due to overwhelming interest in laws like strict voter ID and gerrymandering at higher geographic levels of politics and less interest in local politics as a source of racial inequality (Trounstine Reference Trounstine2009). In this article, I focus attention on how municipal boundaries can be leveraged against racial minority groups through a difference-in-differences analysis of trends before and after Shelby County, decided on June 25, 2013. My findings are contrary to expectations generated from prior research: First, municipalities that were previously covered by Section 5 are not significantly more likely to conduct annexations after Shelby County. Second, I find that even prior to Shelby County, Section 5 municipalities were significantly more likely to conduct Black-diluting annexations than not covered municipalities, and yet these types of annexations do not significantly increase after Shelby County. Moreover, municipalities do not appear to discriminate against Black populations more than non-Black minority populations in their annexation practices.

The first finding highlights the ongoing gap in knowledge about the consequences of removing anti-exclusion regulation and the need for more theory to help explain these findings. Many forms of voter suppression did intensify after Shelby County (Feder and Miller, Reference Feder and Miller2020; Hardy Reference Hardy2020; Herron and Smith, Reference Herron and Smith2015; King and Smith, Reference King and Smith2016), providing a rebuttal against the potential conclusion that problematic annexation activity decreased after Shelby County due to a diffusion of minority voter protection norms. One possibility is that different forms of voter suppression tactics are compensatory—decreases in one type can be accompanied by increases in another type and vice versa. Prior to Shelby County, municipalities were nevertheless still able to conduct annexations significantly associated with Black population share reductions. After Shelby County, these annexations are significantly less likely to happen, but the other types of voter suppression practices increased. Future research could further investigate interactions between various types of minority voter suppression tactics.

The second finding contributes novel quantitative evidence to discussions about racial exclusion in municipal annexations. Prior research on this area has primarily focused on municipal underbounding and its consequences for Black and Hispanic communities at the fringe (Aiken Reference Aiken1987; Durst Reference Durst2019; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Parnell, Joyner, Christman and Marsh2004; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi, Grice and Taquino2007; Wilson and Edwards, Reference Wilson and Edwards2014). I show that municipal annexations are important to understand additionally for their potential impacts on minority populations already living within the municipality. Pre-Shelby County trends in Black-diluting annexations highlight the limited effectiveness of the preclearance requirement when it was in place to prevent the use of annexations to suppress Black population shares. Understanding why Sections 4 and 5 did not effectively prevent Black-diluting annexations and why these annexations in fact decreased after Shelby County—for all municipalities, whether previously covered or not—allows us to be more vigilant about the precise strengths and weaknesses of legislation to prevent racial exclusion in municipal annexations.

This is a particularly pressing concern because Congress is currently considering legislation modeled after Sections 4 and 5 of the 1965 VRA—the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act (JLVRAA). The proposed legislation is modeled after Section 4 and sets a specific formula for determining preclearance. According to what is proposed in Section 4A(b)(2) of the JLVRAA, a municipality conducting an annexation would be subject to preclearance if 1) the voting age population share of a given minority group would decrease by more than 3% as a result of the annexation and 2) at least two separate minority groups in the jurisdiction each comprises at least 20% of the voting age population.Footnote 18 Only 0.85% of the municipalities in my analytical sample fulfill the latter criteria and only forty-nine out of the almost 5000 observed annexations (0.98%) would have been subject to preclearance under the combination of these two requirements.Footnote 19 In addition to only applying to a small handful of jurisdictions, evidence from my study suggests future requirements modeled after the preclearance mechanism in Sections 4 and 5 in the 1965 VRA are unlikely to prevent questionable municipal annexations from still occurring.

Finally, the third finding presents mixed evidence for the Black exceptionalism hypothesis, which posits that there is still a bright Black/non-Black boundary that significantly distinguishes Black residents from other racial minority groups and disadvantages them (Fox and Guglielmo, Reference Fox and Guglielmo2012; Lee and Bean, Reference Lee and Bean2004; Parisi et al., Reference Parisi, Lichter and Taquino2011). I do find that covered municipalities are significantly more likely than not covered municipalities to conduct Black-diluting annexations, whereas there are no significant differences in their frequency of conducting non-Black minority-diluting annexations. However, the rate of non-Black minority-diluting annexations is higher than the rate of Black-diluting annexations. Given scholarship suggesting that anti-minority resentment tends to be uniquely directed towards Black communities (Abascal Reference Abascal2022), it is unclear why trends are in fact more unfavorable towards other non-Black minority residents. Further research should disentangle factors that selectively contribute to bright Black/non-Black racial boundaries to explain these unexpected findings.

There are a few important limitations that provide fruitful avenues for further research. First, there could be measurement error at both the municipal- and block-levels. For the 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 periods in particular, the low rate of validation against the BAS could either be due to a lag in official records of annexation or due to measurement error. While my results are still robust to the subset of annexations validated against the BAS, another study using a different method of identifying annexations may find different trends. Second, my results are robust to annual and two-year intervals of measuring annexations, but I am still unable to determine whether municipalities that annexed did so through one annexation or multiple, additive annexations. Studying each annexation event individually could yield richer information on the relationship between annexation and racial composition, and future research would benefit from identifying sources of data to conduct this analysis. For example, it could be possible that many annexations happened immediately after the Shelby County decision, between June 25, 2013 and December 31, 2013, which I am unable to observe based on annual shapefiles. These two limitations highlight the need for more timely, complete, and official recordkeeping on annexations with enough block-level detail, which would not only help with further research, but also with enforcement of federal laws. Annual trends (Figure A1) show that the number of annexations is slowly but consistently increasing in recent years. Therefore, it is also possible that effects have not yet emerged, such that future research using a longer time span after Shelby County would yield different results.

Third, my analysis does not incorporate information on other boundary changes like incorporations and mergers, which also fell under the purview of Section 5. Unincorporated, predominantly White communities can use incorporation to avoid being annexed into a more racially diverse neighboring city (Miller Reference Miller1981), or if they are already part of the city, secede (Owens and Gillespie, Reference Owens and Gillespie2018). My analysis does not account for these boundary changes, as the vast majority of officially recorded boundary changes are annexations.Footnote 20 Secession movements by wealthy White enclaves in cities have drawn a lot of recent attention, but their occurrence still pale in comparison to annexations. Relatedly, my analysis does not address whether residents at the municipal fringe wish to be annexed or resist it (Durst Reference Durst2018; Miller Reference Miller1981). Similarly, I am unable to address whether minority communities in municipalities encourage or resist the municipality’s annexation plans. Including this data would provide a more complete picture of the experiences of affected communities, and it is an important qualitative aspect beyond the scope of the present study. Lastly, while racial composition is one way of understanding the consequences of annexation for minority groups, I am not able to analyze local electoral outcomes for all municipalities represented in this study to assess whether minority-diluting annexations translate into tangible political consequences. Although my findings highlight the importance of paying attention to how boundaries can be leveraged to shape racial composition, future research could shed light on concrete political outcomes at stake for individuals and communities belonging to these racial groups.

In conclusion, these findings center municipalities as important units of analysis for racial inequality. Building on recent work highlighting municipal practices that exclude racial minority groups (Beck Reference Beck2019, Reference Beck2023; Douds Reference Douds2021; Pacewicz and Robinson, Reference Pacewicz and Robinson2021; Vargas et al., Reference Vargas, Cano, Del Toro and Fenaughty2021), I show how annexations are yet another way municipalities can exert racial control. These findings also provide avenues for further research into how to better craft federal legislation to guard against racially exclusionary behavior. Since municipalities continue to conduct annexations, we should also continue to monitor municipal boundary changes after the Shelby County v. Holder decision. Much attention is placed on the gerrymandering of higher-level boundaries like congressional districts, but gerrymandering of municipal boundaries merits attention and has important implications for macro-segregation and minority political representation (Anderson Reference Anderson2010; Durst Reference Durst2018; Durst et al., Reference Durst, Cai, Tillison-Love, Huang and Henry2021; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi and Taquino2015). Future research on municipal boundaries would benefit from better and more timely reporting of data on annexations at the appropriate geographic levels.

Acknowledgements

Jackelyn Hwang, Asad Asad, Mike Bader, Michael Rosenfeld, and C. Matt Snipp provided extensive feedback to earlier versions of this paper. The author also thanks members and audiences of various workshops and conferences for helpful comments and suggestions. Tyler McDaniel, Vas Kumar and Jessica Chen provided invaluable technical support. Some of the computing for this project was performed on the Sherlock cluster supported through the Stanford Research Computing Center. The Digital Humanities Graduate Fellowship at Stanford University provided partial funding for this project. The author declares no competing interests.

Appendix

Fig. A1. Pre- and Post-Shelby County trends in annexation activity, by type, annual intervals.

Table A1. Validation of identified annexations against the Census boundary and annexation survey