We must stand together. We have to take care of each other. But in a different way than we usually do. As Danes, we usually seek the community by being close together. Now we must stand together by standing apart.

—Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen (Denmark), March 11, 2020Footnote 1

I always treated the Chinese Virus very seriously, and have done a very good job from the beginning, including my very early decision to close the ‘borders’ from China—against the wishes of almost all.

— President Donald J. Trump (United States), March 18, 2020Footnote 2In early 2020, a deadly virus originating in Wuhan, China quickly spread to over two hundred countries and territories, yielding mass casualties, economic contraction, and social unrest. The novel coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV 2), produces symptoms ranging from mild dry cough, fever, and sore throat, to life-threatening cases of pneumonia, multi-organ failure, and septic shock. A not-insignificant percentage of those infected have lost their lives—more than five million people at the time of this writing. Covid-19 has been classified as a slow-moving mass casualty incident (MCI), a deadly catastrophe in which “the available local resources, such as personnel and equipment, are overwhelmed by the number and severity of casualties.”Footnote 3 To avoid overloading their systems, governments the world over responded with stay-at-home orders, quarantines, curfews, and lockdowns—cratering economies and producing massive job losses. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), defined as an “extraordinary event” in which disease threatens to spread internationally to other states, potentially “requiring a coordinated international response” (World Health Organization 2020a).

To track the looming menace, websites such as the Johns Hopkins University dashboard, the Singapore Ministry of Health Upcode, and the Oxford University COVID-19 Government Response Tracker quickly popped up, transforming the advancing pandemic into a macabre spectator sport. Researchers and publics alike were invited to use interactive tools to compare the “curves” of infection and death rates across different countries and draw their own conclusions about which states and locales were responding to the pandemic more effectively. Journalists and analysts began to evaluate the relative success or failure of different countries or nations in handling the crisis; invidious comparisons were made and just as quickly forgotten as each country’s individual rate of new daily infections and deaths were analyzed and evaluated for whether it had been “flattened”, meaning it was under control. Since emerging in Wuhan, Covid-19 spread to every corner of the globe, finally reaching Antarctica in December 2020. Beginning with the first wave of infections, governments were ranked on how well they protected their national economies, how quickly they procured and administered vaccines, and how effectively they shielded vulnerable groups from infection, death, and the economic costs of lockdowns over successive waves and multiple variants of the coronavirus.

At the outset of the pandemic, scholars warned that the forces of nationalism ruled out the coordinated global response recommended by the WHO to minimize the loss of life. Leading international relations scholar Stephen Walt predicted that Covid-19 would “strengthen the state and reinforce nationalism,” as “citizens look to national governments to protect them” (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Burns, Garrett, Haass, Ikenberry, Mahbubani, Menon, Niblett, Nye, O’Neil, Schake and Walt2020), while prominent nationalism scholar Liah Greenfeld projected that “it was transnational institutions, rather than the nation-state, that were likely to fall victim to the pandemic,” (Woods et al. Reference Woods, Schertzer, Greenfeld, Hughes and Miller-Idriss2020, 813). Other analysts ventured that the pandemic was just one more thing that would exacerbate preexisting tensions between the United States and China (Boylan, McBeath, and Wang Reference Boylan, McBeath and Wang2021), while still others forecast a “post-pandemic world” marked by less globalization, free trade, multilateralism, and development cooperation (Bhusal Reference Bhusal2020; Brands and Gavin Reference Brands and Gavin2020).

In the lead article of this symposium penned in early 2020, Florian Bieber predicts that the pandemic would have limited long-term effects on the global level of nationalism because governments were likely to follow their preexisting nationalist trajectories, which vary widely across countries. Indeed, Covid databases quickly revealed stark policy differences to the pandemic from the very beginning: South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and New Zealand crafted science-driven guidelines such as bans on gatherings, quarantines, and contact tracing with the aim of preventing widespread community transmission. New Zealand even implemented a “zero Covid” policy that entailed radical border restrictions. By contrast, both US President Donald Trump and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro downplayed the pandemic, scoffed at masking and social distancing and touted unproven miracle cures such as ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. Trump held packed rallies, while Bolsonaro took selfies with his supporters on the street. Indian prime minister Narendra Modi, too, brushed off warnings by epidemiologists about the seriousness of the virus, leaving millions of migrants unprotected when the government suddenly implemented a hard lockdown at the end of March 2020.

How does nationalism help us make sense of this diversity? Under Westphalian norms of sovereignty, state governments are tasked with safeguarding the health and well-being of their national populations. The challenge is how to aggregate the needs and wants of millions of people into a single "national interest". Whereas classical theorists focused on divining the collective identities and preferences shared by all members of the nation, both modernization and constructivists rightly emphasize the imagined properties of the nation that inform both policy and politics. Benedict Anderson famously described nations as “logo-maps” that represent the boundaries of the national community “beyond which lie other nations” (Reference Anderson1991, 7). Nations, in this view, are better thought of as “map-images” (Shelef Reference Shelef2020) based on a “desert island model,” (Espejo Reference Espejo2020), which are projected in political communication and deployed in policy-making, rather than as material “things-in-the-world.”Footnote 4 When governments craft national policy, in other words, they abstract away from the individuals who make up the nation to the notional needs of the nation as a whole. During national emergencies or crises such as pandemics, sovereigntist movements form around collective images of the idealized sovereign people, whose interests must be defended and voices represented (Jenne Reference Jenne2021).

However, nations are not always visualized in the same way—even in the same society at the same point in time—and these differences can have distributional consequences for the population, particularly during crisis periods. Two images or models of the idealized sovereign community are particularly prevalent in modern democracies.Footnote 5 The liberal nationalist sovereignty, exemplified by the words of the Danish prime minister in this article’s epigraph, implies generous but hardened horizontal borders around the threatened in-group (which extends to the citizens and permanent residents of the state). This geographical closure is juxtaposed against the openness of its idealized demos, permitting governance by experts and scientific elites. By contrast, the ethnopopulist sovereignty envisions more exclusionary national borders—encompassing the core ethnopolitical group, while excluding hostile national others; the demos is understood to belong to “the people”, not elites. I illustrate these competing imagined sovereignties in the case of the United States with political artwork used to rationalize the pandemic policies of former US president Donald Trump versus those of former New York governor Andrew Cuomo. Over the course of the pandemic, both leaders came under intense fire for “failing” to protect their constituents, providing political space for alternative imagined sovereignties that called for different pandemic responses.

Nationalism, Populism, and Pandemic Politics

Under the Westphalian system, each state is presumed to enjoy a monopoly of legitimate authority over the territory and people within its borders.Footnote 6 Once based on dynastic or religious authority, the modern state derives its sovereign authority from nationalism, a political principle according to which “the political and national unit should be congruent,” (Gellner Reference Gellner1983, 1). In consolidated states, ethnonationalism calls for privileging the ethnic majority over those of minorities in the distribution of state resources.Footnote 7 Today, the boundaries of the state are assumed to be coterminous with the nation or core group in the name of which it governs. The concepts are so intertwined in contemporary politics that they are articulated interchangeably and in hyphenated form. Embedded in an explicitly international system, the state is unlikely to lose its national character any time soon (Malešević Reference Malešević2010). Even in today’s highly globalized world, societies have persisted in governing themselves territorially. According to Anthony Giddens, “the modern state, as a nation-state, becomes in many respects the pre-eminent form of power container, as a territorially bounded (although internally highly regionalized) administrative unity,” (Giddens Reference Giddens1987).

To understand the role of nationalism in pandemic policy making, it is useful to conceptualize the nation less as a stable community moving through time and more as an ephemeral and contested image of a territorialized group, to paraphrase Anderson (Reference Anderson1991, 6-7). In the nation-state conceit, the state is the defender of the nation,Footnote 8 which Anderson defines as an “imagined community” that is imagined specifically as flat, horizontal, and lateral, the borders of which abut neighboring nations (ibid.) Within the state’s territorial remit, the national government is deputized to defend the well-being of nationals, who vest their interests in the state.Footnote 9 The legitimacy of the government, in turn, derives from the extent to which it provides for “its nationals” (conceived either broadly as fellow citizens or narrowly as a particular ethnic or political group) by providing collective defense against existential threats.

What does collective defense mean in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic? Historically, pandemics have stimulated popular demands for territorial closure. In the fourteenth century, the bubonic plague ravaged much of Europe. During the Black Death of 1347–1351, as much as one third of Europe’s population perished; subsequent outbreaks of the plague in the centuries that followed decimated the populations of Genoa, Milan, Padua, Lyons, Venice, Marseilles, and Moscow. Recognizing that the pestilence followed trade routes, hard-hit medieval and early European towns placed restrictions on movement, quarantining travelers and commerce.Footnote 10 Even in the premodern age, territorial closures were meant to keep out threats, particularly from threatening “others”. During the 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, disease pathogens were nationalized; American journalists and politicians call the influenza the Spanish Flu even to this day, despite the fact that the first reported cases were in the state of Kansas (Barry Reference Barry2004, 3). Pandemics have also produced exclusionary ethnonationalism, generating nativist, medicalized prejudice that justified restrictions on immigrants, who were seen as carriers of disease (Kraut Reference Kraut2010).

Today, the term national defense implies border defense. It should therefore come as no surprise that the first response of governments around the world to Covid-19 was to close or sharply restrict their ports of foreign egress, despite repeated warnings from the WHO that most transmission occurs at the local level through droplets from close contact with those infected. For this reason, the WHO has consistently recommended social distancing, bans on big gatherings, and mask mandates over closing borders for suppressing outbreaks (World Health Organization 2020b).Footnote 11 Against those recommendations, there was a palpable rise in border nationalism, as governments around the world implemented travel bans, closed off borders, and tightened restrictions on migrants, tourists, and even international students—while at the same time allowing their own nationals to leapfrog border restrictions to return home before lockdowns. Even European Union countries suspended their freedom of movement and imposed export bans on pharmaceutical supplies, despite Italy’s appeals for assistance in the midst of a massive outbreak (Braw Reference Braw2020). Through it all, Covid-19 was configured as a foreign threat, even in countries that were already experiencing widespread community transmission. As vaccines came online in early 2021, there was a rise of “vaccine nationalism” as governments competed against one another to be the first to develop a vaccine that could protect their nation, even poaching one another’s scientific teams (Dyer Reference Dyer2020). “National others”, meanwhile, were largely excluded from, or given lesser access to, state aid. As of May 2021, some 46 million asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants still had not been covered in national vaccination plans (Safi Reference Safi2021).

In many democracies, the pandemic has also given rise to populist demands for political closure around an idealized demos—excluding both national and international elites. Demands for unmediated representation of the vox populi in government spiked dramatically in response to economic uncertainty, anxiety, and hardship caused by infection or fear of infection and lockdown-related job loss (Gugushvili et al. Reference Gugushvili, Koltai, Stuckler and McKee2020), in addition to ontological fears of an invisible enemy that was wreaking havoc from within. Invisible but deadly, pandemics are exactly the sort of crises that serve as grist for the populist mill. Particularly for people who place greater stock in “commonsense” understandings over scientific theories, a microscopic killer can seem simultaneously all-powerful and suspiciously overblown.

Researchers have shown that populist attitudes are associated with conspiracy theories about “liberal” scientists, who are regarded as part of the corrupt, evil, or parasitic elite (Castanho Silva, Vegetti, and Littvay Reference Castanho Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017). To reduce their cognitive discomfort, people search for simple explanations for catastrophic events like pandemics (Douglas, Sutton, and Cichocka Reference Douglas, Sutton and Cichocka2017).Footnote 12 This has led to a rash of conspiracy theories about the origins of the virus—for example, that foreign actors worked together with disloyal domestic groups to spread the virus to weaken the nation, as in the “plandemic” theory that the Chinese government created Covid-19 in a secret laboratory, experimented with its effects in Wuhan (which was walled off from the rest of the country), and exported it to western countries as a form of bio-warfare (Eberl, Huber, and Greussing Reference Eberl, Huber and Greussing2021). National elites, multinational corporations, and shadowy international cabals are believed by QAnon supporters to be using mass vaccination as a vehicle to microchip the population so they can be more easily controlled. These and other folk theories have helped to fuel anti-lockdown protests around the world; in Italy, the Gilet Arancioni (orange vests) movement of so-called anti-vaxxers, Covid deniers, and an assortment of lockdown-vulnerable regular people coalesced around movements to open up national or local economies.

Populist leaders seek to harness revolutionary movements by promising to reconfigure the demos to return the reins of government to the “real” or “ordinary” people (Canovan Reference Canovan2005). In doing so, they idealize a sovereignty that is disembedded from liberal institutions and the liberal international order (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Kaltwasser2018; see also Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010; Mounk Reference Mounk2018; Müller Reference Müller2016). It is a sovereign imaginary in motion, in a permanent state of becoming. As populist scholar Natalia Urbinati (2019, 4-5) wrote, populist leaders are not dictators; they “disfigure democracy “but remain within democratic bounds. This implies that populism is a radical critique of liberalism—it calls for dismantling liberalism in the name of achieving a “true” democracy for the “unrepresented people”. In formulating their response to Covid-19, populist leaders the world over vowed “to go to the people”, rather than rely on technocrats, experts, or scientists. On the 2020 campaign trail, for example, Trump declared his own top scientist, Anthony Fauci, a “disaster”, while mocking Biden for wearing a large mask and listening to scientists (Associated Press 2020a). Boris Johnson likewise sought to listen to other voices besides scientists, rejecting their recommendation to lock down the country, failing to curb a massive wave of infections (Ward Reference Ward2020).Footnote 13 By aligning the government’s pandemic response with the perceived or expressed preferences of their constituents, populist heads of state create an apparently unmediated transmission belt between the people’s will and state-level pandemic policies. Although traditionally an outsider ideology, several state leaders have built their populist brand on fighting “the establishment”, in a David-versus-Goliath battle on behalf of the downtrodden against powerful globalist elites and their domestic enablers.

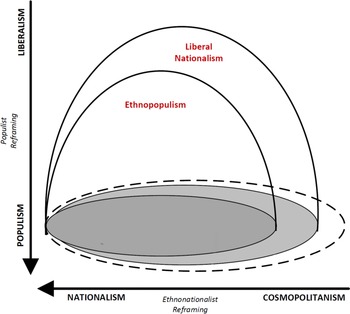

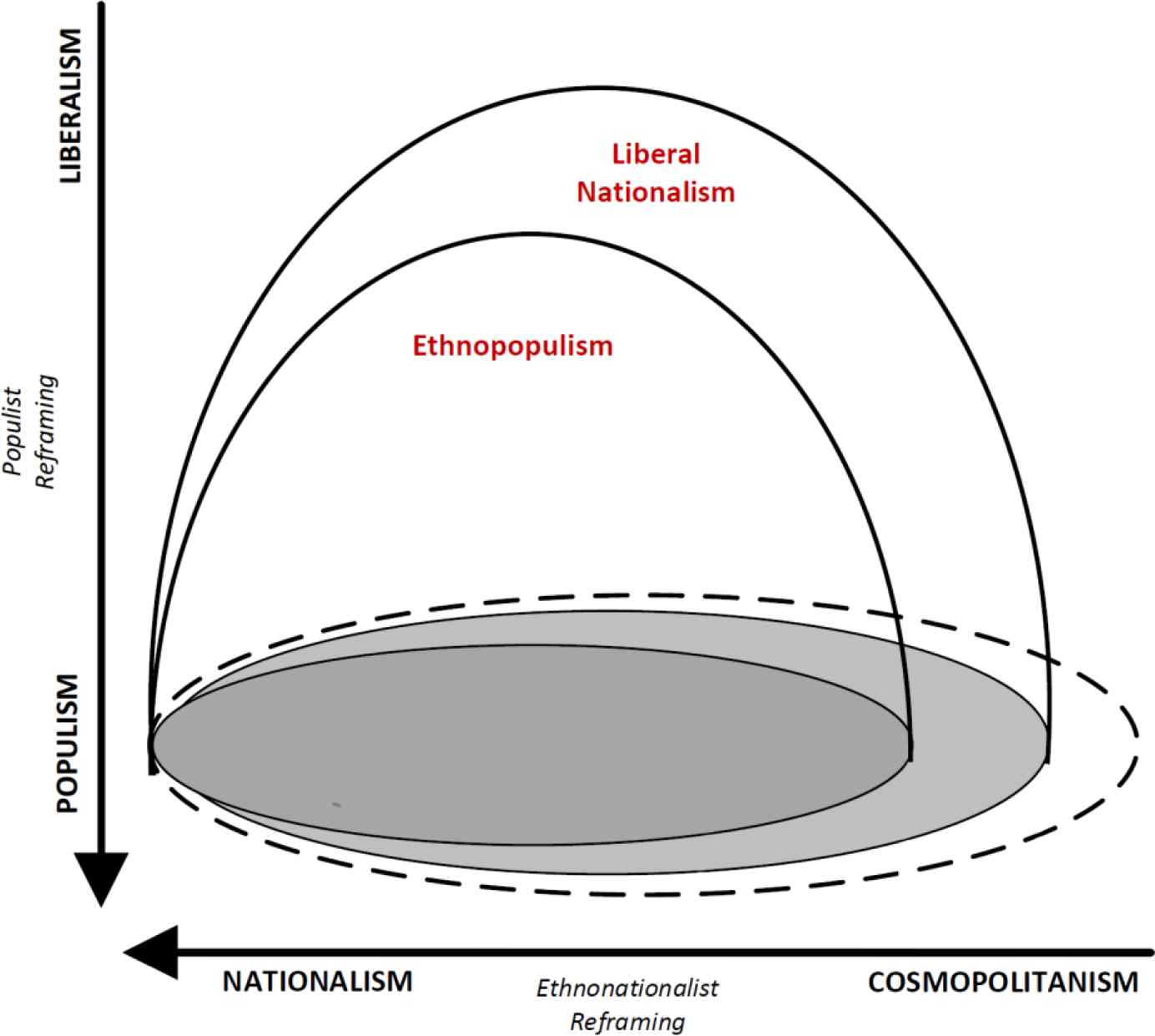

Populism and nationalism both serve to inscribe the boundaries of the idealized sovereign community more restrictively—excluding elites and “national others”, respectively. However, they differ in the political space that they divide, with nationalist frames used to restrict access to state resources, while populist frames are used to restrict access to representative institutions. Essex School discourse analytic scholars Benjamin De Cleen and Yannis Stavrakakis argue similarly that nationalism is an antagonistic in-out discourse that excludes non-nationals, while populism is an antagonistic up-down discourse that excludes elites or the political establishment (De Cleen Reference De Cleen, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017; De Cleen and Stavrakakis Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017; De Cleen et al. Reference De Cleen, Moffitt, Panayotu and Stavrakakis2020). These discourses or what we call sovereigntist frames are used by political agents to reconfigure the height and breadth, respectively, of the idealized sovereign community (Jenne Reference Jenne2021; Jenne, Hawkins, and Silva Reference Jenne, Hawkins and Silva2021).

Keven Olson describes these collectively shared imaged as imagined sovereignties Footnote 14 that mark the boundaries of the pre-political in-group (Olson Reference Olson2016). In democracies, these images are actively and continually articulated by political leaders, who use them as a means of competing for political office and as a crude template for discharging their duties while in office.Footnote 15 Instantiated in law and policy practice, political agents discursively ‘reframe’ the nation by projecting the national form in a more or less exclusionary way (see also Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996; Suny Reference Suny1993; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2018).Footnote 16 Figure 1 depicts a 2.5 dimensional projection of two common types,Footnote 17 which roughly map onto Liah Greenfeld’s well-known taxonomy of “dissimilar interpretations of popular sovereignty,” ranging from “individualistic-libertarian” to “collectivistic-authoritarianism.”Footnote 18 Although not considered here, nondemocratic governments are more likely to respond to such threats with an even smaller authoritarian nationalist imaginary that configures the interests of the nation and the regime leadership as organically fused; their leaders score wins for the nation through transactional policies that ensure the survival of the regime through the coercive power of the state.Footnote 19 In the following sections, I offer a sketch of the first two sovereign imaginaries with illustrations.

Figure 1. Dueling imagined sovereignties.

Liberal Nationalist Responses

In the liberal nationalist imaginary, humanity is divided geographically into territorially siloed communities, each of which has the right to self-determination or self-governance. Liberal nationalists configure the nation in broad terms, including both minorities and sometimes also non-citizens (see, for example, Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka1996).Footnote 20 Yael Tamir, a leading proponent of liberal nationalism as a form of government, argues that liberalism and nationalism are not only compatible, but nationalism serves as the necessary glue for liberalism because “no individual can be context-free, but … all can be free within a context,” (Reference Tamir1995, 14). David Miller, another defender of liberal nationalism, argued that although such “identities are inevitably partly mythical in nature, yet they answer a pressing modern need, the maintenance of solidarity in large, anonymous societies,” (Reference Miller1993, 3). Liberal nationalists favor an interconnected and interdependent world composed of nation-states that cooperate to solve global problems, while each state is tasked with protecting the welfare of its entire national population.Footnote 21 International relations scholar John Ruggie (Reference Ruggie1982) coined the phrase “embedded liberalism” to refer to the balance that states struck after the Second World War between maintaining open international trade and free capital flows and intervening domestically to ensure economic stability and social security to members of the nation.Footnote 22 During periods of economic expansion, members of liberal societies tend to be “parochial altruists”, meaning that they will be open to immigrants when doing so is so expected to benefit their compatriots (Kustov Reference Kustov2021). During economic downturn and crisis, however, the interests of the national in-group are given priority.

In the context of pandemics, liberal nationalism prescribes the broadest possible defense of diverse segments of society through robust border control as well as technocratic science-based methods to control the virus at the local level. Consistent with this expectation, even open political systems responded to the rapid spread of Covid-19 with reflexive nationalist closure—tightening and then relaxing border restrictions on the movement of people in and out of their countries across successive waves of coronavirus infections. At the same time, they remain committed to relatively free trade and supra- and transnational governance—maintaining rule of law domestically, protecting individual freedoms so far as possible, and attempting to balance the health of their nationals against the health of their national economy. In the liberal nationalist worldview, individual choice and freedom is predicated upon unflinching national defense.

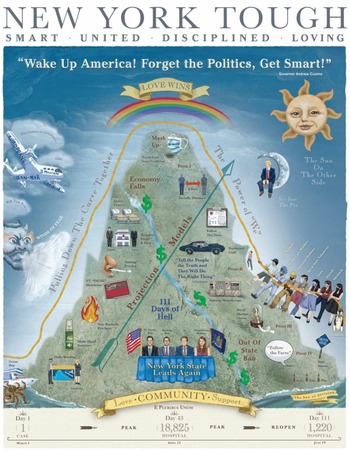

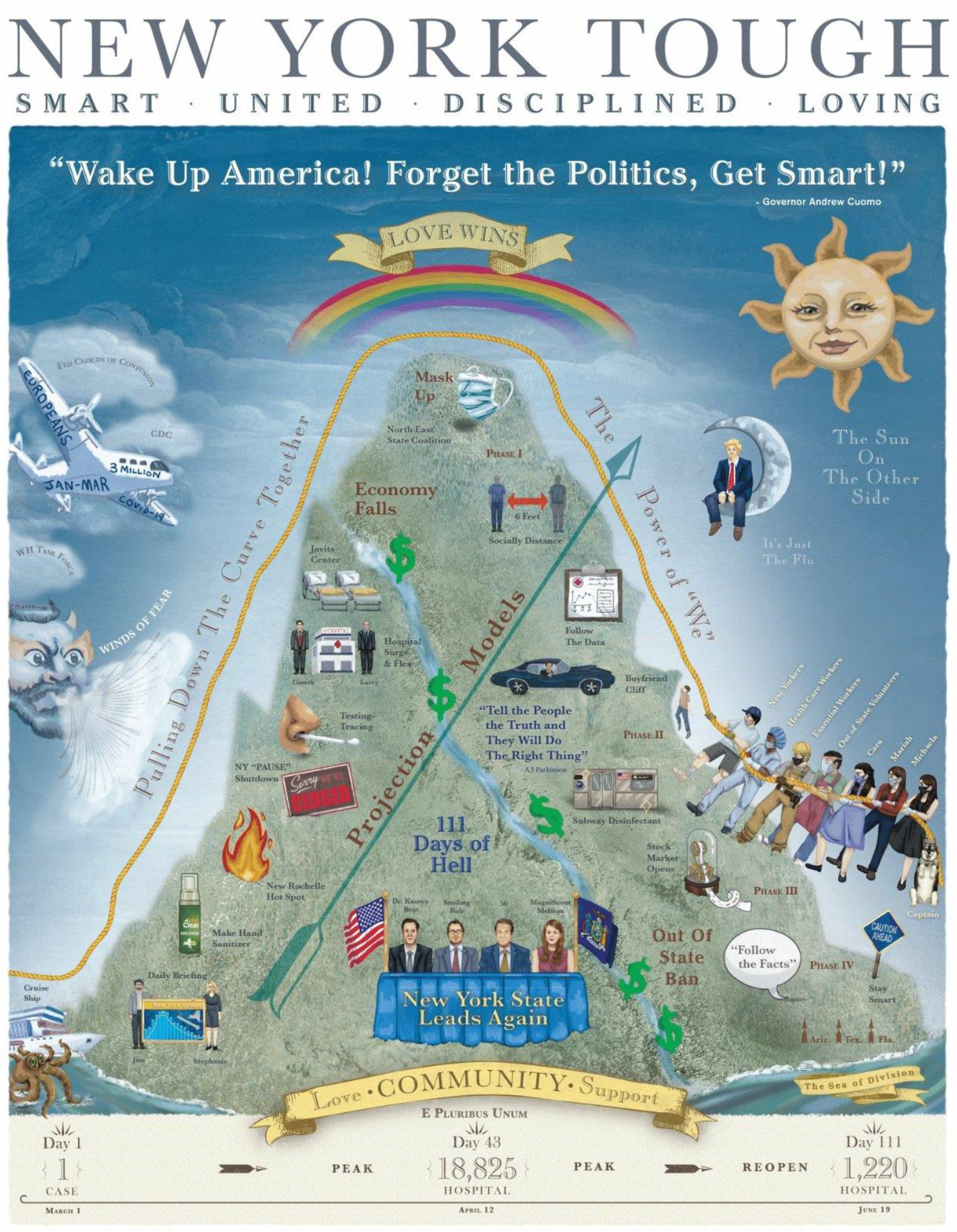

This sovereignty is reflected in a poster commissioned by former New York governor Andrew Cuomo to communicate his pandemic approach to the public (figure 2). Available on the New York governor’s official website in early 2020, the image recalled the style of posters of William Jennings Bryan, from the Progressive Era at the turn of the 20th century.Footnote 23 It depicts a “national” community of New Yorkers from different ethnic and occupational backgrounds coming together to “pull down the curve” of Covid-19 infections and deaths. At the bottom of the image are the words “love,” “community,” “support,” and “E. Pluribus Unum’ (out of many, one). This is an image of a multiethnic nation that looks after one another; it promises to protect the welfare of this diverse community and follows rules and science in order to do so. The poster exhorts the public to defer to science, enjoining them to “mask up” in the conviction that if you “tell the people the truth, they will do the right thing”.

Figure 2. New York Tough poster

Source: Reproduced with permission from Governor Cuomo’s office.

Nonetheless, this is also a bordered community. The poster suggests that New York’s boundaries must fortified against multiple external threats, including three million coronavirus cases entering the United States from Europe in January–March 2020—reflecting fears that European tourists were spreading Covid-19 to the United States. Further threats stem from populist “winds of fear” coming from the White House Coronavirus Task Force. There is a cruise ship containing Covid-infected passengers, and Donald Trump is featured as the out-of-touch man in the moon declaring “it’s just the flu.” This is a visual depiction of an inclusive national community beset by threats coming from without, against which every New Yorker must be protected.

Former German federal chancellor Angela Merkel projected a similar imaginary in her address to the nation on March 18, 2020, in which she asserted that since German unification, or even the Second World War, “there has not been a challenge for our country in which action in a spirit of solidarity on our part was so important,” (Merkel Reference Merkel2020). While affirming the importance of freedom of movement in a democracy, she argued that social distancing and masking—while onerous—“are vital at the moment in order to save lives.” Based on the recommendations of top scientists, the government implemented a strict lockdown and secured airport hangars, old trade fairs and hotels to repurpose into makeshift hospitals to care for the hospitalized.

New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern took the protection of the country’s population even further with her “zero Covid” policy, vowing to fully eradicate the virus on the small island. Months later she recalled how the government had arrived at this choice: “I remember my chief science adviser bringing me a graph that showed me what flattening the curve would look like for New Zealand. And where our hospital and health capacity was. And the curve wasn’t sitting under that line. So we knew that flattening the curve wasn’t sufficient for us” (Associated Press 2020b). Both leaders remained committed to protecting the health of their nationals at all costs, while explaining their actions in an open and transparent way going forward, so long as the pandemic continued.

Consistent with the tenets of liberal nationalism, these governments adopted pandemic responses broadly in line with the recommendations of WHO officials and mainstream scientific community—encouraging (or mandating) wearing face masks and practicing social distancing, prohibiting large gatherings, and vigorously enforcing all of the above, and later, administering safe and effective vaccines to their national populations. Internal controls on movement—lockdowns, social distancing and mandatory mask orders—were aligned with the injunction to protect the health of the nation, broadly conceived.Footnote 24 The liberal nationalist sovereignty also calls for striking a careful balance between liberal openness and national defense: the government must prioritize the well-being of its nationals, while working together with regional and international organizations to identify global solutions. These priorities are often in tension with each other, as evidenced in the European Union’s slow vaccine development and rollout. The bloc’s response to the pandemic was slow and collaborative, leading to significant delays in vaccine delivery. For countries like Hungary, which secured Russian and Chinese vaccines without waiting for approval from the European Medicines Agency, or the United States and United Kingdom, which invested heavily in developing their own vaccines to inoculate their citizens first, vaccine delivery was relatively quick. This contrasts with the vaccine rollout in France and Germany, which refrained from pursuing country-first vaccine policies in order to strengthen EU collective action and negotiate cheaper prices for vaccines (Apuzzo, Gebrekidan, and Pronczuk, Reference Apuzzo, Gebrekidan and Pronczuk2021; Chazan Reference Chazan2021). The resulting lags in vaccine delivery were seen by some as a performative weakness of liberal nationalism in health emergencies.

Ethnopopulist Responses

As uncontrolled outbreaks of Covid-19 undermined public trust in government, populist movements coalesced around demands for political closure against self-serving, exploitative elites. Although a wave of non-nationalist (left-wing) populism was always a possible response to the pandemic, we saw very little of it at the state level—most likely due to simultaneous demands for national-territorial closure against a threatening “foreign” virus in societies.Footnote 25 For this reason, Covid-19 outbreaks have served as fertile mobilizational ground for ethnonationalist populist—or ethnopopulist—movements to “take back the country” from ethnic minorities, refugees and the sold-out (liberal) elite class. Ethnopopulism privileges a political subset of that ethnonational dominant group—the “real” national core. Ethnopopulists pledge to protect the “people-nation” from hostile elites and nonnationals, who are believed to be conspiring to undermine the dominance of the ethnopolitical core.Footnote 26 In the ethnopopulist worldview, the truly “authentic” sovereign community extends only or primarily to a particular political or social subset of the dominant ethnopolitical group—“the people” who are a subset of “the nation” (supporters of Donald Trump in the United States, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, or Narendra Modi in India). Other contemporary right-wing populist governments, including Bolsonaro’s and the Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice) government in Poland, continually declared that the people’s will must prevail against “globalists” who were working in league with communist nations. In the context of pandemics, blaming out-groups or designated others is one way that societies have of making sense of the devastating effects of contagious diseases, while also making them seem controllable.

Ethnopopulism has also been described as an “elite strategy for winning votes and concentrating power” (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2020, 318). This calls attention to the ways in which embattled leaders employ hyper-exclusionary rhetoric to remain in power within still-competitive electoral systems. At the rhetorical level, ethnopopulists reconfigure the idealized sovereign community so restrictively that large swaths of the population are deliberately left out of its imagined boundaries—implying that they are to be excluded from the full protections of the state. Ethnopopulism “blends these threats “by propagating narratives whereby enemies from beyond (migrants, immigrants, ethnic minorities) couple or even conspire with enemies from above (the EU, UN, IMF [International Monetary Fund], ‘global elites’ or foreign powers) to undermine or even de-nationalize the nation-people” (Jenne Reference Jenne2018, 549; see also Vachudova Reference Vachudova2020; Zellman Reference Zellman2019; Stroschein Reference Stroschein2019; Bieber Reference Bieber2018; Hronešová Reference Hronešová2021; De Cleen and Stavrakakis Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2020; Heiskanen Reference Heiskanen2020; Koch Reference Koch2020; Jovanović Reference Jovanović2020). Conspiracy theories perform a vital function in mobilizing support for right-wing populist movements by identifying nefarious elites believed to be scheming with globalists and national others to destroy the “true” people (Wojczewski Reference Wojczewski2021).

This antagonistic sovereignty comes to life in figure 3, a Covid-19-themed political cartoon penned by Ben Garrison, a pro-Trump American cartoonist. Here, we see both horizontal and vertical sovereign reframing in action. The dragon is China or the Chinese Communist Party, which menaces the entire world. The cartoon not only depicts both enemy nations and elites as threats, but as conjoined threats working together to destroy victim nations of Hong Kong and Tibet. Notably, Democratic leaders are actually riding the marauding Chinese dragon; Bill and Hillary Clinton are perched on its spine, along with then-candidate Joe Biden, who is shown holding a bag of money to symbolize his collusion with the Chinese Communist Party. Former secretary of state Henry Kissinger—derided by Steve Bannon in his War Room: Pandemic YouTube Channel as a “Davos man” who has taken “blood money from Xi”—also rides the Chinese dragon. It is an image of globalist elites colluding with a powerful external enemy (representing compounded threats from above and beyond), wreaking havoc not only on the American nation, but on the world as a whole.

Figure 3. Ben Garrison Cartoon

Source: Ben Garrison (reproduced with the permission of the artist)

The presidency of Donald Trump offers a textbook example of ethnopopulism during the coronavirus pandemic. The former president pointedly and continually referred to Covid-19 as the “China virus,” while simultaneously minimizing the risk and harms of the virus and hawking folk coronavirus remedies over the advice of his top scientists and his own Centers for Disease Control. He reportedly dropped an ambitious testing program due to his perception that the coronavirus was just a “blue state” problem. In the federal distribution of much-needed ventilators and personal protective equipment, the administration prioritized Republican over Democratic-led states, employing in-group favoritism in the distribution of federal coronavirus aid (Stieb Reference Stieb2020). The administration simultaneously sought to cut Obamacare and other assistance programs for low-income communities, which would have affected African American and Hispanic populations disproportionately. Such discriminatory policies, also known as welfare chauvinism, appear to enjoy significant support in the Republican base; conservatives were also significantly more likely than liberals to favor international travel bans as a solution to Covid outbreaks (Su and Shen Reference Su and Shen2021). Channeling the anti-lockdown preferences of his populist supporters, Trump slammed governors and mayors who imposed strict pandemic restrictions, while holding campaign rallies around the country that are estimated to have led to thirty thousand infections and more than seven hundred deaths (Bernheim et al. Reference Bernheim, Buchmann, Freitas-Groff and Otero2020). There is also statistical evidence that Trump’s use of terms such as “Kung flu” and “Chinese virus” triggered a rise in anti-Asian hate speech on Twitter. Hate crimes against Asians are estimated to have increased 150 percent from 2019 to 2020 (Hart Reference Hart2021).

Brazilian president Bolsonaro offers a second example of ethnopopulist framing. As infections began to spike in the country, he dismissed it as “a little flu,” proclaiming himself to be a strong, athletic man who was invulnerable to the virus. Like Trump, he went to war with his own health ministers, firing two in quick succession over their objections to his promotion of hydroxychloroquine, an unproven remedy for Covid-19. Also like Trump, he repeatedly blamed China for the virus and deliberately went on “walkabouts” to meet his supporters face to face, calling on citizens to ignore isolation orders. He denigrated state governors from the political opposition as “a bunch of scoundrels” whose restrictions would lead to unemployment and “undue economic damage” (Sandy and Milhorance Reference Sandy and Milhorance2020). His popularity remained intact in the early months as a direct consequence of emergency payments to Brazilian citizens, but dipped precipitously when the death toll spiked in early 2021 (Rosati Reference Rosati2021).

A third ethnopopulist response can be found in India, where sectarian tensions were already on the rise, due in part to the actions of the populist nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party government, which introduced a discriminatory Citizenship Amendment Act in 2019. In early March, a rapid acceleration of coronavirus cases in March 2020 was sourced to a Muslim religious ceremony in Tablighi. Although outbreaks were later traced to Hindu religious ceremonies as well, Islamophobic rhetoric surged on social media in discussions about the virus. Instagram pages @Hindu_Secret and @Hindu_he_hum accused Muslims of willfully spreading the virus; hashtags such as #Corona Jihad and #Tablighi Virus trended on Instagram and Twitter. Although Prime Minister Narendra Modi refrained from hyper-exclusionary rhetoric himself, his government held health briefings that included a separate category for Tablighi-related infections, reinforcing the public perception that Muslim practices presented a public health hazard. As the number of cases across the country exploded, attacks spiked against Muslims who were perceived as carriers of the disease (Rajan and Venkatraman Reference Rajan and Venkatraman2021). Except where democratic institutions are strong, populist governments appear to have performed worse than non-populist governments in suppressing outbreaks (Cepaluni, Dorsch, and Dzebo Reference Cepaluni, Dorsch and Dzebo2021b) (Even populist leaders who responded to the pandemic effectively in the beginning later put the interests of their administration over public health; see Buštíková and Baboš Reference Buštíková and Baboš2020.).

Success Theater and Flipping the Script

If a government is perceived as failing to protect their nation-in-need, the performative crisis can become the site of political struggle.Footnote 27 In the case of Covid-19, governments seen to have failed to manage their outbreaks are at risk of losing legitimacy. A poor performance can lead to the end of a leader’s career or even the end of the political regime. In such cases, the leader may attempt to recapture legitimacy through “success theater,” which business writer Eric Ries defines as “the work we do to make ourselves look successful” in the face of evidence to the contrary (Reference Ries2011, 54). As policy failures in the face of Covid-19 accumulated, incentives also mounted for political leaders to exaggerate their successes and play down their failures. Regime de-legitimation creates the space not only for a new leader, but for an alternative governance model that can provide superior protection to the nation during crisis. It also creates incentives for incumbent leaders to engage in aggressive image management to regain popular legitimacy as a means of hanging onto power.

The leaders of Kosovo and Mongolia made numerous missteps in early 2020 that led to abrupt resignations (BBC News, March 26, 2020). In 2021, New York governor Andrew Cuomo also resigned from office amid months-long calls for impeachment—not only over charges of sexual misconduct but over revelations that he had inadequately protected the elderly from infections and doctored statistics to cover up the number of deaths in nursing homes—all in violation of his liberal nationalist creed (Young and Gronewald Reference Young and Gronewold2021). Taking direct aim at the liberal nationalist responses of mostly Western governments, right-wing populist groups mobilized local resistance to national lockdowns across the developed world. From Italy to France to Germany and beyond, right-wing parties have leveled a range of criticisms against liberal nationalist governments—calling for stronger lockdown measures against non-native groups (National Rally leader Marine Le Pen), dismissing the counsel of government scientists, and insisting that lockdowns and mask mandates be abolished as “authoritarian” (Vox in Spain and Alternative for Germany in Germany) (Wojczewski Reference Wojczewski2021). Matteo Salvini of the League Party in Italy castigated Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte for failing to “defend Italy and Italians” with “armour-plated borders” against purportedly disease-carrying migrants from rescue ships (Luca 2020, 31; Tondo Reference Tondo2020).

We have also seen the discrediting of ethnopopulists over the course of the pandemic—most notably in the United States. In November 2020, a majority of US voters rejected President Trump’s model of pandemic management, tipping the election decisively against him.Footnote 28 The new US president, Joe Biden, offered a starkly different policy approach to American voters. In his first presidential address on the pandemic, Biden implored his audience to “follow the scientists and the science” to “protect … the American people,” to “work together” to protect the vulnerable and the essential workers. In his speech, he reminded his listeners that “government isn’t some foreign force in a distant land,” but “all of us,” at the same time condemning “vicious hate crimes” against Asian Americans (Associated Press 2021). After the first few months of his administration, with the aid of a massive coronavirus economic stimulus and a rapid vaccine rollout, two-thirds of Americans approved of Biden’s handling of the pandemic response (Kahn Reference Kahn2021). Although US borders remained just as closed, the new administration focused less on controlling refugees from the Southern border and more on protecting the nation from Covid-infected travelers, illustrating the divergent policy concerns that flow from the different sovereign frames (Alden Reference Alden2021).Footnote 29

Sometimes a discredited government can redeem itself through learning and policy adaptation. Arguably, this could be seen in UK prime minister Boris Johnson’s decision to scrap the government’s laissez faire pandemic response in spring 2020. The Tory leader had originally recommended that elderly people should isolate while the rest of the general public continue its normal activities. Among other things, he counseled UK citizens to “basically just go about [your] normal daily lives … the best thing you can do is to wash your hands with soap and hot water while singing Happy Birthday twice,” (Conn et al. Reference Conn, Lawrence, Lewis, Carrell, Pegg, Davies and Evans2020). The implied goal was to achieve herd immunity quickly, if not painlessly. Confronted by a massive surge in cases and deaths, and after being hospitalized in intensive care and almost dying from the virus himself, Johnson eventually came out in favor of lockdowns, social-distancing, and masks. He later acknowledged that the wisdom of his earlier choices was “an open question” because “for the first few weeks and months” the government had not understood the virus (Kuenssberg Reference Kuenssberg2020). Nonetheless, despite his early course correction, Johnson continued to have a fraught relationship with his top scientists, partly in response to outbidding on the right from the strongly anti-lockdown wing of the Conservative backbenchers.

Conclusions

Over the past two years, we have seen governments around the world implement Covid-19 policies that broadly conform to their prior nationalist trajectories, as Bieber expected. I have argued that these enterprises are grounded in divergent images of the idealized sovereign community (see Cynthia Miller-Idriss for a similar typology [Woods et al., Reference Woods, Schertzer, Greenfeld, Hughes and Miller-Idriss2020, 810–13]). For leaders of liberal democracies like German Chancellor Angela Merkel and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, that image was liberal nationalism, yielding a science-based, technocratic, liberal approach that extends protection to the entire nation, broadly conceived. For Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and US President Donald Trump, that image was ethnopopulism, which prescribes a redistribution of state resources and political representation from out-groups to the ethnopolitical in-group (The Economist 2020). Migrants and refugees are configured in both sovereignties as out-groups and potential disease-carriers that must be segregated from the nation. This helps us make sense of both the widespread failure to manage the spread of Covid-19 among migrant and refugee communities and the over-reliance on border restrictions to manage outbreaks.

The conceptualization of nationalism as variably inclusive sovereigntist frames that can be used by both state and local leaders alike challenges the reflexive statism in much of the nationalism literature. We can see these dueling sovereignties at play in the discursive struggles between the Bolsonaro and the governors of liberal states in Brazil, between Trump and the liberal governors of blue states, and between the US president Joe Biden and the governors of red states, who themselves have locked horns with the mayors of liberal cities over Covid-19 policies such as public mask mandates and social distancing in schools. This shows that nationalist framing is operative in Covid responses not only at the state but also at the local level--like Matryoshka nesting dolls.

Bieber concludes his article optimistically that “there is nothing inevitable about the dominance of exclusionary nationalism” because “at a critical juncture, different paths are available,” (Reference Bieber2020, 13). I agree with Bieber’s point that the pandemic afforded leaders a great deal of discretion in crafting pandemic policy. Although their initial responses were a product of prior sovereigntist framing, state leaders routinely veer off-script, suggesting that they enjoy considerable discretion over how they protect their nationals from the virus. The open contestation over competing imagined sovereignties within the same political system—often at different levels of government—also suggests that these trajectories are less stable and uniform, more flexible and constantly contested, than is usually acknowledged. In other words, there is value in conceptualizing “the nation” as a model or practice rather than a “thing-in-the-world”, as it reminds us that these trajectories may not be as “sticky” or preordained as commonly believed.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sherrill Stroschein, Christopher LaRoche, Semir Dzebo, Liliia Sablina, Matthijs Bogaards, Dieter Reinisch, Xymena Kurowska, Nassim AbiGhanem, Barbora Valikova, Dominik Sipinski and other members of the Conflict and Security Research Group (ConSec) at Central European University for useful feedback on previous drafts of this paper. I also benefited from editorial feedback from Ned Whalley, Harris Mylonas and an anonymous reviewer at Nationalities Papers.

Disclosures

None.