Xi Jinping's 习近平 perceived power has impacted government workings from Beijing to the grassroots. The administration's anti-corruption and (re)centralization campaigns, unveiled in November 2012 and 2013 respectively, reconcentrated power at the central level.Footnote 1 This has intensified an atmosphere of uncertainty for local officials, making “once self-confident cadres begin to grow palpably afraid.”Footnote 2 Whether (re)centralization has impacted China's distinctly decentralized local policymaking, particularly local policy experimentation, remains unclear. Where local governments were previously encouraged to experiment, some observers contend that (re)centralization reduces local decision-making power and prevents experimental policymaking, while anti-corruption efforts heighten political risk.Footnote 3 Others argue that the Chinese regime is primarily concerned with self-preservation and local experimentation is vital to its continued resilience, suggesting that discouraging policy experimentation threatens regime survival.Footnote 4

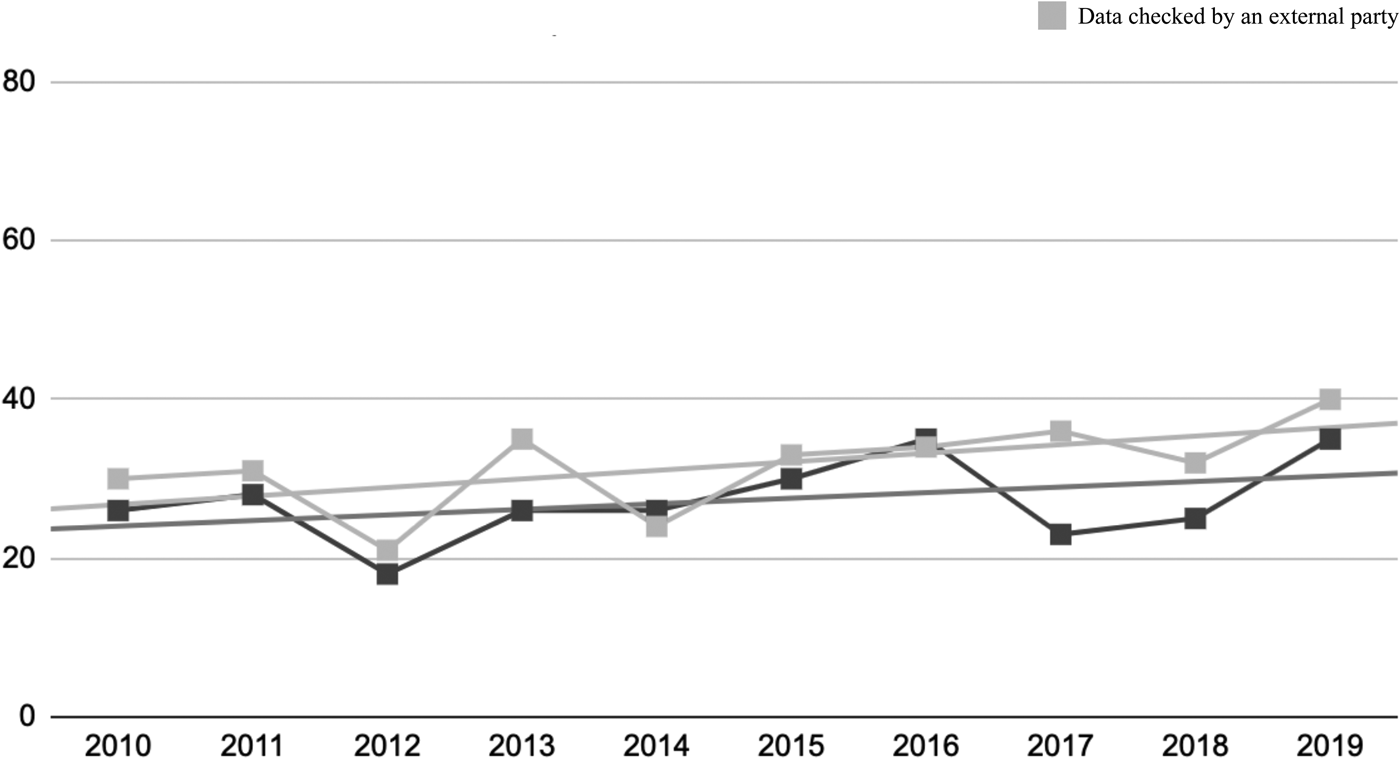

Before posing this article's overarching research question – how has local policy experimentation changed under Xi Jinping? – we must first question if anything has changed. The literature offers two conflicting answers. The first contends that Xi's (re)centralization drive has led to a dramatic decrease in local experimentation.Footnote 5 This is difficult to measure when experiments often begin without formal approval and are not necessarily called “experimentation.” To address this, we analysed the opening passages of all official regulatory documents (difang guifan xing wenjian 地方规范性文件) published between 2010 and 2019 by the people's municipal governments of ten diverse cities and found an increase in the proportion of regulations which authorized, called for or built upon local policy experiments.Footnote 6 Even the “less innovative” central region saw a distinct upward trend in experimentation.Footnote 7

Here, the literature offers a second answer, suggesting that increased uncertainty and risk under Xi encourages local compliance with central commands, therefore continued experimentation must be in accordance with a central demand for decentralized innovation.Footnote 8

It is from this second answer and two case studies that we depart. Although the Chinese policy process has changed under Xi, experimentation has not necessarily declined. Rather, experimentation remains such a vital component of policymaking under “top-level design” (dingceng sheji 顶层设计) that the centre seeks to “steer” local behaviour towards experimentation. Drawing on “political steering theory” and insights gained from two city-level experiments to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), we suggest that explicit changes in systemic pressure caused by political steering from the top have transformed experimentation from a choice to an immediate obligation. As such, in contemporary China, we may no longer be talking about “experimentation under the shadow of hierarchy”Footnote 9 nor is experimentation foremost dependent on the “political personalities” of individual policymakersFootnote 10 and the “policy innovation imperative” motivating them.Footnote 11 Rather, what we see is “experimentation under pressure,” a concept which seeks to further refine those mentioned above to explain forced policy experimentation under Xi Jinping.

Policy Experimentation Revisited

Scholars often use the terms policy “experimentation” and “innovation” interchangeably. Some see policy innovation as any act of converting “ideas and concepts into new policies or policy instruments,” and policy experimentation as something initiated by higher administrative levels.Footnote 12 Others contend that higher-level governments do not initiate experiments, but rather select “successful” grassroots experiments for emulation.Footnote 13 Innovation is a single, integral part of the policy experimentation process; local governments initiate policy experimentation cycles by operationalizing policy innovations.Footnote 14 Policy experimentation is a multidirectional process wherein some aspects are decentralized and others centralized, incorporating bottom-up policy innovations into top-down policymaking without sacrificing central control.Footnote 15 However, the literature does agree that policy experiments must be new to that jurisdiction and the result of local action, not central imposition.Footnote 16

The mainstream literature largely argues that increased risk under Xi has led to a decline in local policy experimentation.Footnote 17 Some approach this observation theoretically, as resulting from increased central interference in policymaking.Footnote 18 Others highlight a causal centralization-decentralization dichotomy, arguing that dismantling subnational governments’ discretionary power reduces willingness to experiment and paralyses the local policy process.Footnote 19 Research on Chinese policy processes has long emphasized this dichotomy, downplaying the absolute authority of the centre in steering decentralized policymaking. Scholars speak of the centre “suffocating” local initiatives, a “broken policy process” and a rule-based “iron cage” for local officials.Footnote 20 The centre's “firm grip” on decision-making power, however, may not prevent experimentation, even as it steers local behaviour,Footnote 21 nor does local experimentation necessarily equal an “erosion” of central power.Footnote 22 “Experimentation under hierarchy,” as conceptualized by Sebastian Heilmann and others, is a “correcting mechanism” balancing state planning with local innovation – complementing rather than contradicting hierarchical control.Footnote 23

The centre can steer local behaviour by monopolizing the power to recognize experiments as “successful.”Footnote 24 For example, although the “Shunde 顺德 model” of auctioning state-owned enterprises (SOEs) was “much disputed” locally, central recognition meant this experiment became national policy.Footnote 25 Without recognition, it might have stalled, like electoral experiments in Sichuan, which were halted by the centre despite widespread popular support.Footnote 26 Policy experimentation has always been a process vulnerable to central intervention at any stage, distorting otherwise organic local outcomes.Footnote 27 Similarly, competition for central recognition historically pressured local governments to be first-movers, not followers; different localities may have similar policy goals, but their methods vary hugely.Footnote 28 The absence of a local “contagion effect” in Chinese policy experimentation supports this assertion: “The appeal to devise new policy innovations is so high that officials refrain from emulating the measures of neighbouring locations.”Footnote 29

Not all “successful” experimental policies are as locally unpopular as the Shunde model, however. The experimental policy process allows the centre, which controls the permissive space in which experimentation occurs, to effectively gather information on popular local demands to incorporate into real policies. Experimentation thus performs an important feedback function for the regime, appeasing public demand and tying the interests of diverse social actors to regime survival.Footnote 30

Subjected to central steering, local policymakers use experimentation to cope with upper-level commands which conflict with immediate local or personal objectives. Local governance requires resources which are sometimes controlled by, for example, private-sector actors.Footnote 31 Local policymakers must bargain for resources they lack, like capital, by offering resources they control, such as allowing non-state actors access to policymaking processes.Footnote 32 Guanxi 关系, an institutional arrangement referring to relationships between actors, creates “discrepancies in access to resources.”Footnote 33 Local officials leverage guanxi to “relieve pressure” from the centre and, sometimes, reverse it.Footnote 34 Relationships with higher-level patrons can increase the chances of a local policy experiment being recognized as successful and reduce risk; a lack of patronage can prevent local officials from experimenting at all.Footnote 35 Under Xi, seeking higher-level support sees local officials “requesting authorization” before experimenting.Footnote 36 Like the risk-reducing patronage condition, requesting authorization provides local actors with much-needed political (approval/recognition) and material (funding) resources. Local policymakers lacking state funding turn to private sector alliances built through “continued exchanges of favours, emotions and resources”: guanxi.Footnote 37 These alliances are “endlessly negotiated,”Footnote 38 but the central state's authority is always “looming” in the background.Footnote 39

As the literature shows, policy experimentation is not only a means of central control over local officials or a feedback mechanism, it also provides bargaining opportunities for policymakers lacking resources needed to provide effective governance. As such, preventing experimentation seems neither to benefit the Chinese regime nor local governments. Why, then, would the Xi administration consider discouraging it?

Theorizing Experimentation under Pressure

As this brief literature review shows, local policy experimentation performs several important functions. It is a means of controlling China's vast local government apparatus via central recognition of local policy innovation. It channels feedback between diverse actors (local government, private sector, the public) and the regime. Today, experimentation is a centrally controlled security valve that relieves and exerts pressure on lower-level bureaucracies according to central interests. In the context of our conceptual approach of experimentation under pressure, we need a theoretical framework which addresses two questions. First, how has the central state increased interference in local experimentation under Xi Jinping? Second, how does local government behaviour reflect this? We suggest “political steering theory,” which departs from an analysis of the central state's steering capacity and local governments’ governability, as a useful way to explain how experimental policymaking is going through a period of fundamental change.Footnote 40

Gunter Schubert and Bjørn Alpermann define steering capacity as the centre's ability to control lower-level behaviour using a combination of steering instruments.Footnote 41 Governability is how local governments react to steering efforts from above, i.e. through avoidance strategies like coping and shirking, or counter-steering against top-down commands. Although the centre increased steering capacity in some areas as early as the mid-1990s, multiple sources of systemic pressure (steering instruments) have converged under Xi, making it nearly impossible to disobey direct administrative commands.

Scholars often describe aspects of steering theory when conceptualizing the Chinese system. For example, the concept of steering capacity has already permeated the literature on Chinese policymaking, although it is often referred to in terms of (re)centralization or top-level design. Kevin O'Brien and Lianjiang Li describe the centre's “increasing pressure” in policy implementation and the “rightful resistance” against it, which could also refer to steering capacity and governability.Footnote 42 Similarly, Frank Pieke describes the sometimes conflicting “pressures” built into the Chinese bureaucracy that control local political agency, just like steering instruments.Footnote 43 Local officials themselves use this language of “pressure” when explaining the rationale behind starting a policy experiment.Footnote 44

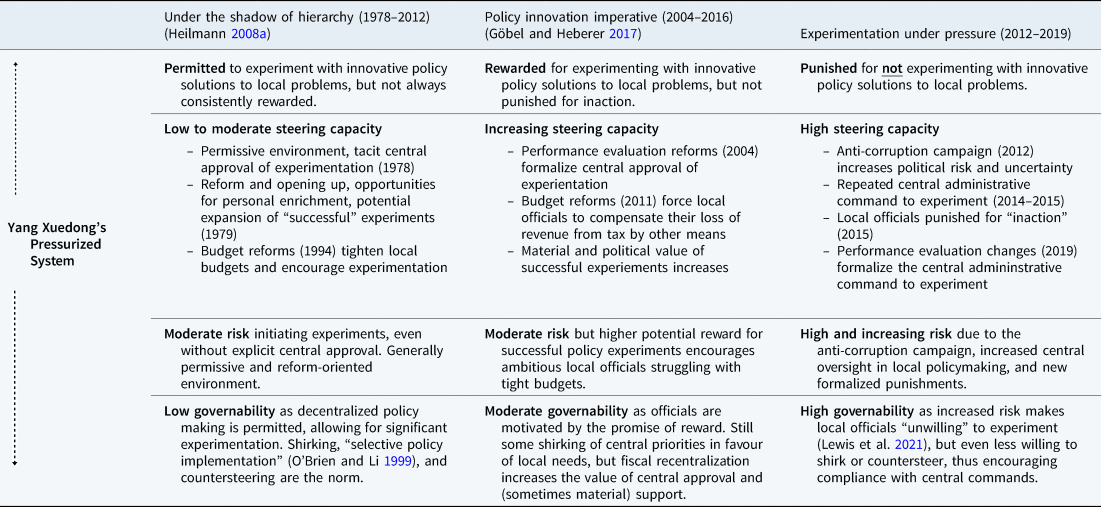

This tendency persists within Chinese academia. For example, the “pressurized system” concept developed in the 1990s explains how the centre exerts pressure on local officials using different steering instruments such as task setting, resource allocation, performance evaluation and material incentives.Footnote 45 As Yang Xuedong argues, the “core pressure” of top-down administrative commands is not enough to steer local behaviour; the centre needs multiple sources of pressure – i.e. it needs to increase its steering capacity.Footnote 46 Although Yang and colleagues identify an “intensification” of pressure under Xi, many of the steering instruments they describe were developed before Xi's inauguration and have since been radicalized.Footnote 47 As such, there is some overlap (Table 1), which we seek to overcome by characterizing our time periods according to the introduction of new steering instruments, which increase pressure on local governments to experiment while also increasing the political risk of doing so.

Table 1: From under the Shadow of Hierarchy to Experimentation under Pressure

Increased pressure on local governments to experiment ![]()

Increased political risk involved in experimentation ![]()

While we see increased pressure as the intended result of targeted central steering – aspects of which precede Xi – increased political risk is a more subtle form of central control. Risk refers to the purposeful creation of insecurity, felt by local policymakers when they implement policies. The policy experimentation literature highlights different manifestations of political risk that are unique to the Xi era: the risk of punishment under the auspices of Xi's anti-corruption campaign;Footnote 48 the risk of punishment if an experiment fails to meet targets;Footnote 49 and the risk of punishment should an experiment unwittingly cross a central red line.Footnote 50 To this we add one more: the risk of punishment for ignoring or shirking Xi's repeated command to experiment. While the risk of punishment forces local governments to experiment, the other political risks keep experimentation free from corruption and measurably goal-oriented while also forcing local governments to remain hyper aware of central red lines and directives. It is unsurprising that local officials may feel “less willing” to experiment yet do so despite increased risk.Footnote 51

As detailed in Table 1, reform-era experimentation “under the shadow of hierarchy” was defined by low steering capacity and minimal central intervention, moderate but manageable levels of personal risk and low governability, as local governments were willing and able to shirk or even counter-steer against central commands. However, we can observe an overall upward trend in steering capacity, risk and governability that began with the fiscal reforms of 1993–1994, strengthening the centre's power over local budgets and pushing local governments to experiment with “creative strategies in order to meet their ordinary expenditure requirements.”Footnote 52 Limited local finances had long convinced local officials to challenge “the centre's restrictive strategy” through economic policy experiments, such as with FDI.Footnote 53 The financial reward of experimentation, for governments and individuals, often outweighed the shadow of hierarchical punishment. The “policy innovation imperative” period introduced steering instruments designed to reassert central control and involvement in local experimentation. Although the possibility of hierarchical reward and punishment existed and conditioned behaviour in the first period, the 2004 “Decision on enhancing the Party's ability to govern” and 2005 “Several opinions regarding the deepening of reforms of the cultural system” explicitly rewarded “refined” cadres committed to “incessantly strengthening their practice” and “innovation orientations.”Footnote 54 Existing steering instruments like budget reforms also intensified, “placing all government revenues under [central] budgetary management.”Footnote 55 All served to encourage experimentation, both in response to new performance evaluation rewards and budget limitations, and therefore increased governability. The result was that even underdeveloped and backward regions, like Ganzhou 赣州 in Jiangxi province, launched their first major experiments.Footnote 56

Although steering instruments of earlier periods encouraged and even rewarded local governments for experimenting autonomously, cadres were never explicitly punished for not doing so. A “hold-to-account” mechanism existed to punish local officials generally, but the “actual risk” of punishment was considered low.Footnote 57 The current period, then, is defined by steering instruments that (re)centralize control at the top by using increased political risk and clear, comprehensive and formalized punishment to ensure high levels of local compliance with central commands. For example, the anti-corruption campaign, paradoxically, functions as both a hard-steering mode ensuring central control and a method of soft-steering, using signal politics to perpetuate an environment of uncertainty, particularly among local officials.Footnote 58 This uncertainty keeps local officials self-steering, demonstrating their compliance by paying heightened attention to direct administrative commands such as speeches and directives given by the top leadership. As our case studies show, local officials directly cite these commands while experimenting. Where others argue that uncertainty and risk make officials less willing to experiment, we suggest that they also prevent them from shirking or ignoring the direct administrative command to experiment for fear of becoming the next “fly” punished for corruption.Footnote 59

The direct administrative command to experiment began with Xi's clean governance campaign right after he took office. Even before his inauguration as CCP general secretary in 2012, he had actively punished cadres for “inaction” (bu zuowei 不作为).Footnote 60 From there, he began constructing an image of the “good cadre” who “dares” to face problems and “take responsibility” (chengdan zeren 承担责任), while turning against officials who “do not seek merits, but seek no demerits”Footnote 61 – “bureaucratic autocrats” who avoid experimentation and innovation when they are discerned to be too personally risky.Footnote 62 This command was formalized in the CCP Central Committee's 2019 Notice on cadre evaluation, which explicitly stated that if “the official does not display enough entrepreneurial spirit […] is afraid to face contradictions or unwilling to get into trouble,” he will not receive a positive evaluation or promotion.Footnote 63 “Inaction” is now considered corruption and a precedent was set for punishment in mid-2015.Footnote 64 Where previous administrations made it possible to creatively sidestep implementing central commands to the letter, avoiding Xi's explicit command to experiment now means punishment.Footnote 65

The performance evaluation system had long included both “material rewards” and punishments like the “one-vote veto,” where failure to complete certain tasks resulted in a performance score of zero and no chance of promotion.Footnote 66 However, the one-vote veto was not previously applied to experimentation. Compared to the “policy innovation imperative” wherein ambitious officials are willing to risk failure for a “quick and dramatic promotion”Footnote 67 because “the normal route of upward mobility is slow and uncertain,”Footnote 68 this latest addition to the incentive structure actively punishes those who do not experiment.

“Experimentation under pressure,” therefore, describes a central–local relationship wherein the centre seeks to pressure local officials to experiment, and increased steering capacity makes doing so more effective, with the observable result that even local governments that were unlikely to experiment before Xi are experimenting. We conceptualize experimentation under pressure as a steering mode that describes both central pressure and local government responses – that is, behaviour adopted to reduce risk while still visibly experimenting. Thus, with the aim of conceptualizing the interaction of multiple, sometimes contradictory top-down steering methods, experimentation under pressure refers to the conditions steering local experimental behaviour in contemporary China.

As our chosen policy field leaves officials particularly vulnerable to corruption, it is a good test for whether risk and uncertainty outweigh the direct administrative command to experiment and the risk of a one-vote veto. Our case studies show local officials from diverse backgrounds still experimenting, suggesting that balancing the promise of promotion against the risk of punishment does not account for variation in the occurrence of experimentation.Footnote 69 Even in a policy area as inherently risky in terms of corruption as FDI, and even in regions with minimal experience with policy experimentation (and even less experience experimenting with FDI policy), experimentation is still happening. It is from this puzzle that our case studies depart.Footnote 70

Two Case Studies: Foshan 佛山 and Ganzhou 赣州

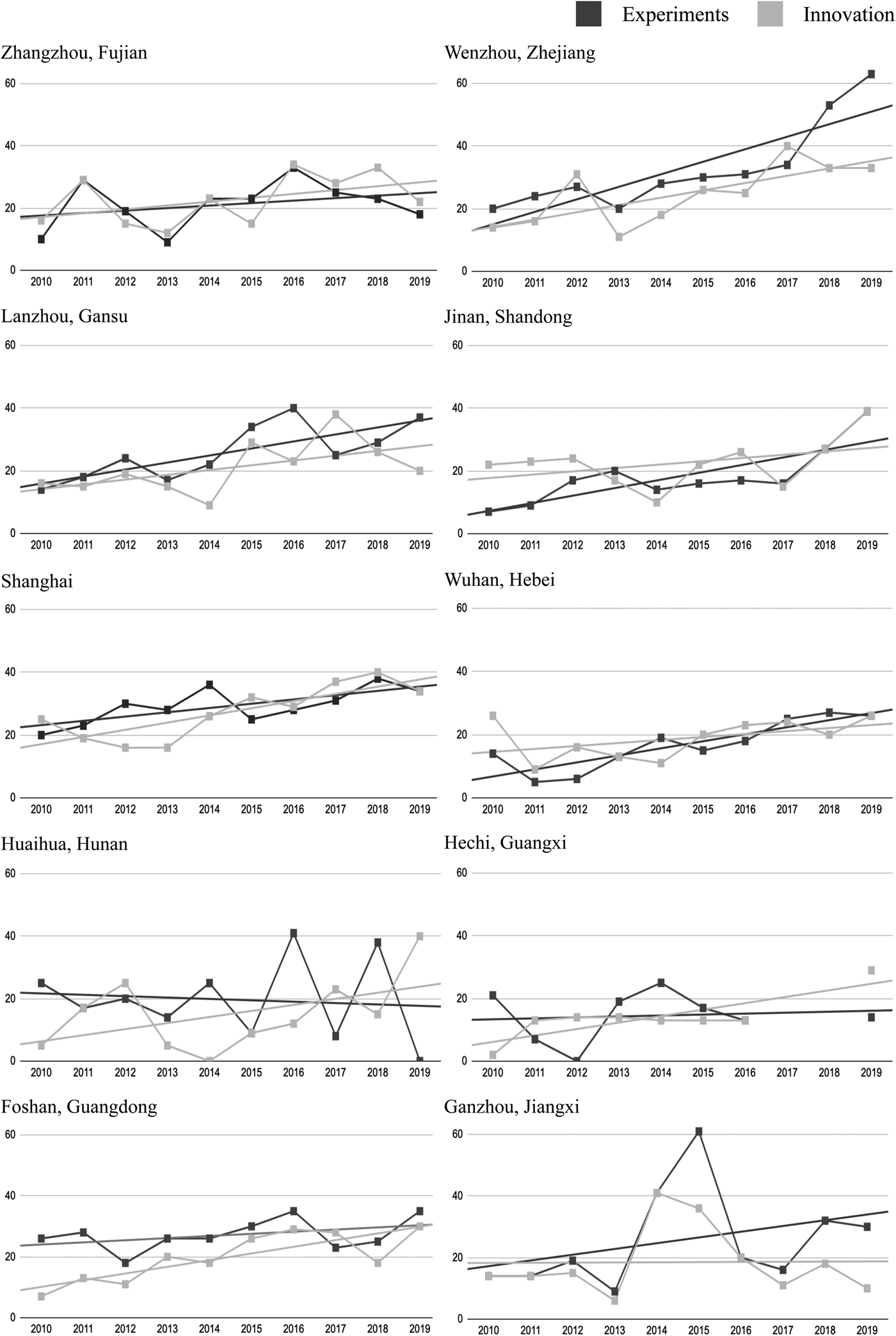

In our analysis of over 3,000 official documents across ten diverse locations between 2010 and 2019, we found a general upward trend in experimentation, with only one case showing a slight decline (Figure 1).Footnote 71 Documents were coded as “experimental” if they authorized, called for or built upon “trials,” “demonstrations,” new “models” or “pilots” – what Sebastian Heilmann would call “experimental points.”Footnote 72 Experimentation occurred in fields as diverse as government transparency, citizen policy consultation and workplace rights. This analysis enabled us to identify time periods of decreased or increased experimental activity. All cases see a drop in experimentation at some point between 2012 and 2014, but pick up again by 2016, following a series of Xi's speeches in 2014–2015 identifying “innovation, coordination, green(ness), openness and sharing” as the foundation of the “four comprehensives” (si ge quanmian 四个全面) development concept.Footnote 73

Figure 1: Experimentation and Innovation (% of All Official Documents 2010–2019)

The Party theory department interpreted the “four comprehensives” as calling for “innovation in all aspects of governance,”Footnote 74 previously cited as referring to investigation, research and reform in policymaking, i.e. experimentation.Footnote 75 To test the relationship between Xi's “four comprehensives” and experimentation, we looked at citations of “innovation” within local regulations and found an upward trend. We then looked at specific mentions of the “four comprehensives” and found that documents pertaining to experimentation made up 67 per cent of mentions. Although some cities may have a patchy relationship with experimentation, all seem to be responding to Xi's various commands to experiment.

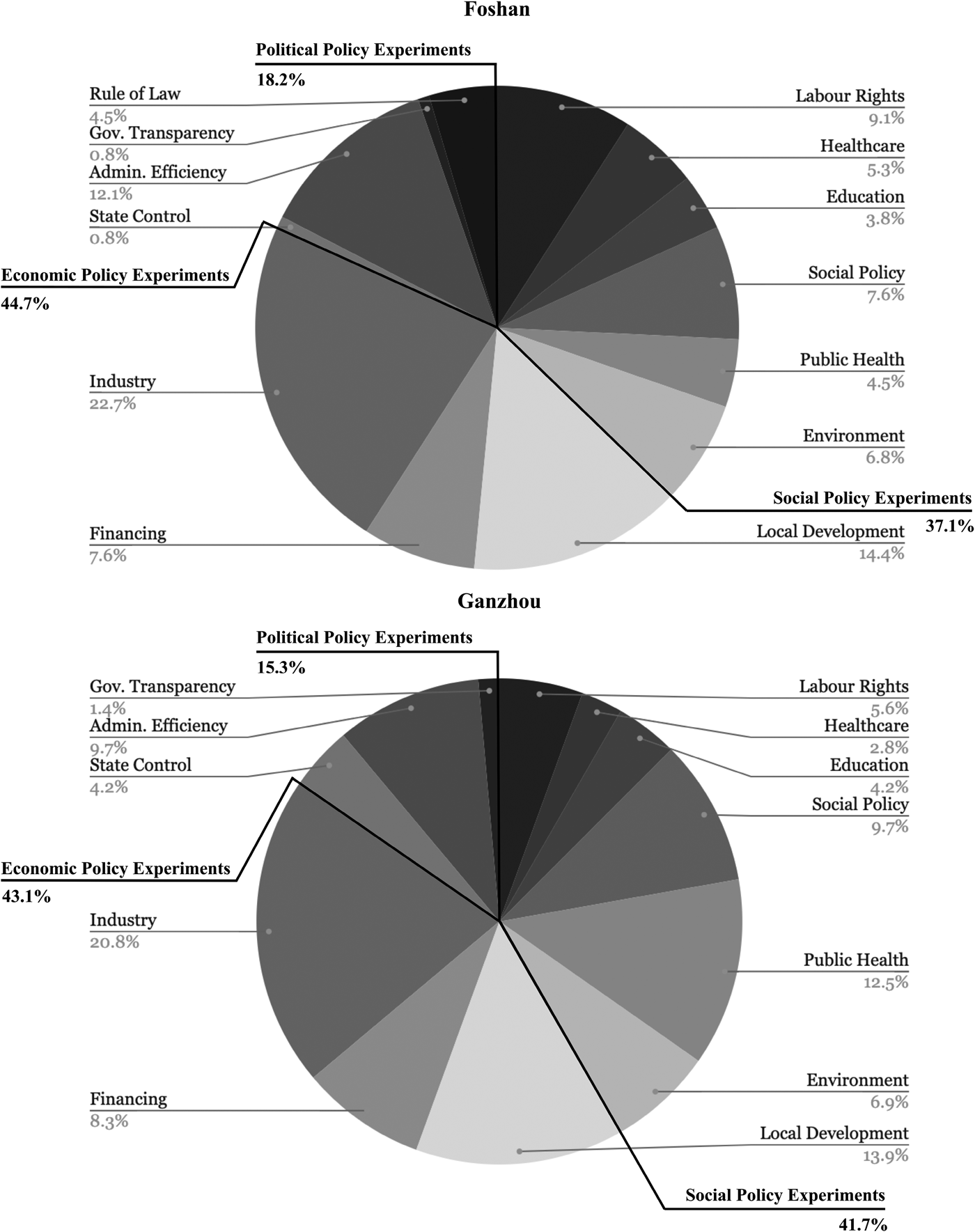

To gain a better understanding of “innovation in all aspects of governance,” we selected two very different case studies to represent one case from an “innovative” region (Foshan) and one from China's “least innovative” region (Ganzhou).Footnote 76 Despite differing local conditions, which influence whether experimentation in a specific policy area will occur in a set province,Footnote 77 the proportion of experiments categorized as political, social or economic was similar in both cases (Figure 2). Explicit central policy priorities, such as industrial upgrading and environmental protection, were equally prioritized.

Figure 2: Experimentation by Policy Area in Foshan and Ganzhou (2010–2019)

Despite this, local conditions are relevant. In economically well-developed Foshan, local officials have a long history of successful policy experimentation, initiating more ambitious political experiments, such as those seeking to ensure “a government ruled by law” and public oversight in government transparency (Figure 2).Footnote 78 In Ganzhou, we see pertaining to developmental issues in “lagging” regions, for example in public health issues and social policy transfers. Ganzhou initiated more experiments that explicitly sought to assert state control, such as increasing Party oversight.

Both Foshan and Ganzhou prioritized local development, which required significant local spending.Footnote 79 Here, our chosen policy field is important because foreign investment provides the fiscal resources needed to implement policies mandated by the centre, such as social policies that “put the people first” and “respond to their wishes,”Footnote 80 as well as to ensure local development. Inbound FDI has, however, plummeted in recent years,Footnote 81 declining from 6.2 per cent of GDP in 1993 to 1.5 per cent in 2018.Footnote 82 Local officials face difficulties attracting FDI, even in well-developed coastal regions:

After more than 30 years of rapid development, the driving force behind our locational advantages continues to decay. At the same time, inland cities continue to learn, clone our past practices, and are now rushing to catch up. [We] have gradually lost our comparative advantage. If [we] do not further reform and initiate new policies … to renew these advantages, [we] will hit a dead end.Footnote 83

In both experiments discussed below, FDI is seen as a means to achieving local development aims. However, while Foshan has a history of successful experiments in this policy area, Ganzhou does not, making an experiment there with FDI even more risky.

Local conditions can reduce the risk of experimenting under pressure in specific policy fields, thereby encouraging experimentation. However, another potential variable is that some officials may be more sensitive to risk than others. Xiaobo Hu and Fanbin Kong suggest that those close to retirement age are more likely to avoid risk through “inaction.”Footnote 84 Orion Lewis, Jessica Teets and Reza Hasmath's typology suggests that “autocratic” personality types are considerably less likely to experiment under Xi.Footnote 85 While Foshan's experimental policymaker fits the bold, risk-taking, “entrepreneurial” personality type and was only 48 when experimenting, Ganzhou's policymaker conforms to the more hierarchically minded “strategic autocrat” type and was 59 – one promotion away from retirement. Strategic autocrats are not as risk averse as “bureaucratic autocrats” but they pay close attention to central signalling and are acutely aware of risk, particularly the risk of negative evaluation. Despite these differences, both experimented.

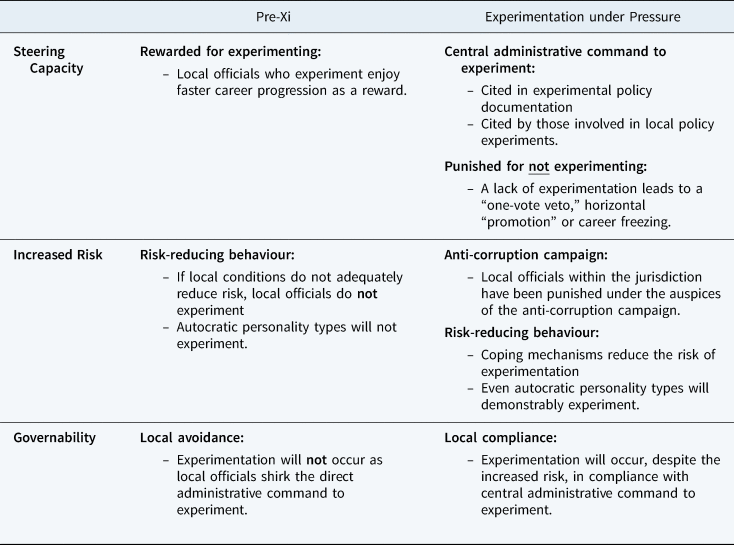

As we posit above, policy experimentation under Xi Jinping has become obligatory rather than optional. However, we are not only interested in how the centre might steer the behaviour of local officials, enforcing the administrative command to experiment, but also in how local officials respond to upper-level steering by reducing the inherent risk of experimentation while still experimenting. Some steering instruments and risk-reducing behaviour precede Xi's inauguration; others form part of a new policymaking context of experimentation under pressure (Table 2).

Table 2: Indicators of Experimentation under Pressure

Fieldwork for both case studies was conducted during visits to China in September 2018 and June 2019, and in follow-up discussions with 39 subnational governments involved in attracting FDI – mostly bureaus of commerce (BofCom hereafter) and investment promotion agencies (IPAs hereafter).Footnote 86 The Foshan BofCom provided policy documents and arranged interviews with those officials directly involved in initiating the Foshan experiment. Jiangxi province's BofCom provided information on Ganzhou's experimental taxation policy and put us in contact with the Ganzhou BofCom for further clarification. We then supplemented these discussions with news reports, media interviews and secondary commentary on the policies in question.Footnote 87

Foshan: hiring foreigners to attract FDI

As Foshan officials were experimenting long before Xi's direct administrative command told them to do so, we did not expect to see a dramatic increase in the proportion of regulations involving experimentation (Figure 3). Based on the Foshan case at its outset in 2013, the experimentation follows the pre-Xi model. However, in 2015, Foshan's direct geographical competitors visited the city to learn from this experiment, challenging pre-Xi understandings of local experimentation.

Figure 3: Experimentation as a % of All Official Documents (Foshan)

Foshan has a long history of initiating policy experiments without explicit central approval, many of which have involved FDI.Footnote 88 When Zhou Zhitong 周志彤, director of the Foshan BofCom, published a job advertisement to hire foreign nationals for local government posts before applying for approval, he followed the pre-Xi precedent of experimenting first and asking permission later. In July 2013, three months after the advert was published and six months after the launch of the experiment, bureau officials drafted a formal proposal to the city government requesting approval and funding.Footnote 89 The project was already well under way when, in 2014, it gained central approval: the Ministry of Commerce declared Foshan “an example” for others to follow.Footnote 90 As the former vice-director of the Foshan BofCom told us: “As the first domestic government agency to hire foreign employees, this innovative approach was reported to the national Administration of Foreign Experts Affairs, receiving recognition and affirmation.”Footnote 91

Zhou's “unusual experiment” attracted the attention of international media outlets and positioned Foshan as an award-worthy investment location.Footnote 92 When discussing his reasons for initiating this experiment, Zhou cited his experience with civil servants in Italy and South Korea.Footnote 93 Pre-Xi experimentation often included consultation with non-Chinese actors, companies and institutions without direct central oversight.Footnote 94 Since 2013, however, the centre has curbed local governments’ engagement with foreign actors through hard-steering instruments such as targeted budget cuts.Footnote 95 Zhou's experiment itself created channels through which foreign actors could engage with local officials, thus preserving pre-Xi patterns of local experimentation.

Similarly, pre-Xi experimentation often involved close collaboration with the private sector. For example, Foshan entrepreneurs “spontaneously” developed China's first shareholding enterprise in 1982.Footnote 96 However, the anti-corruption campaign has made public–private collaboration politically dangerous. Regardless, Zhou actively sought private-sector engagement and the innovation he operationalized was a direct result of this consultation:

The original idea came from Mr Wu Shengbo 吴胜波, then-president and CEO of Osram Asia Pacific. In 2013, I asked him about Foshan's foreign trade and investment promotion … As the effectiveness of past methods has diminished significantly, what new methods can we use to our advantage? He replied: to further open-up, Foshan should expand from opening to things, to opening to people [and] might consider recruiting talents from all over the world to form an international team.Footnote 97

Perhaps stemming from his own private-sector background, Zhou is an “entrepreneurial” official who is genuinely interested in changing the current way of doing things, regardless of personal risk.Footnote 98 As the vice-section chief of the Foshan IPA noted: “It was a creative and brave decision at that time because no government had hired foreigners as real government employees before. There were no examples or existing principles to follow.”Footnote 99

The Foshan case supports the argument that “entrepreneurial” personality types are less susceptible to changes in hierarchical pressure and therefore are more likely to continue experimenting under Xi.Footnote 100 Entering the emulation stage of the experimental policy process, however, some unexpected developments emerged: “After the central government learned that Foshan had hired a foreign team to attract investment, Guangzhou and Huizhou 惠州 came to learn from Foshan['s foreigner experiment].”Footnote 101

If Guangzhou or Huizhou initiated their own competing foreigner policy, it would challenge the argument that Chinese policymakers do not follow the policy experiments of their direct competitors and that there is no local contagion effect.Footnote 102 The Sino-European Industrial Services Zone in Shunde, Foshan's competitor, had already followed the city's example and hired a foreign staff member in 2016.Footnote 103

Towards the end of the pilot-phase of the Foshan project, there is evidence of horizontal promotion and career freezing. In the early years, officials involved in Zhou's experiment were promoted: the-then Party secretary Liu Yuelun 刘悦伦 moved up to leadership roles in the provincial capital; the section chief overseeing the foreign team was made vice-director of the BofCom; and staff members moved up internally. Since then, however, a lack of either observable results, new experiments or nationwide expansion has stalled the careers of those involved. Zhou remains at the bureau after a leave of absence for health reasons and, according to colleagues, has had his workload reduced. The vice-director was transferred horizontally to the position of secretary general of the Foshan Association of Industry and Commerce (Foshan shi gongshangye lianhui 佛山市工商业联会). None of the first generation of foreign employees remain. Only former-Party secretary Liu has continued to innovate in his role as Guangzhou Committee chairman of the provincial CPPCC, forging new partnerships to promote the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area.Footnote 104

The Foshan case suggests that rather than encouraging one-off, high-impact policy experiments, experimentation under pressure mandates continuous innovation and “entrepreneurial spirit.”Footnote 105 Further, despite increased risk, experimentation continued unabated in Foshan with the introduction of bold, new policy solutions, which could later be integrated into national policymaking. However, even in regions with a long history of successful experimentation, the increased risk of experimenting under Xi's “top-level design” has led to horizontal promotion and career freezing, thereby influencing the policy equations of local officials, as evidenced by the emergence of immediate local policy learning.

Ganzhou: offering tax incentives to attract FDI

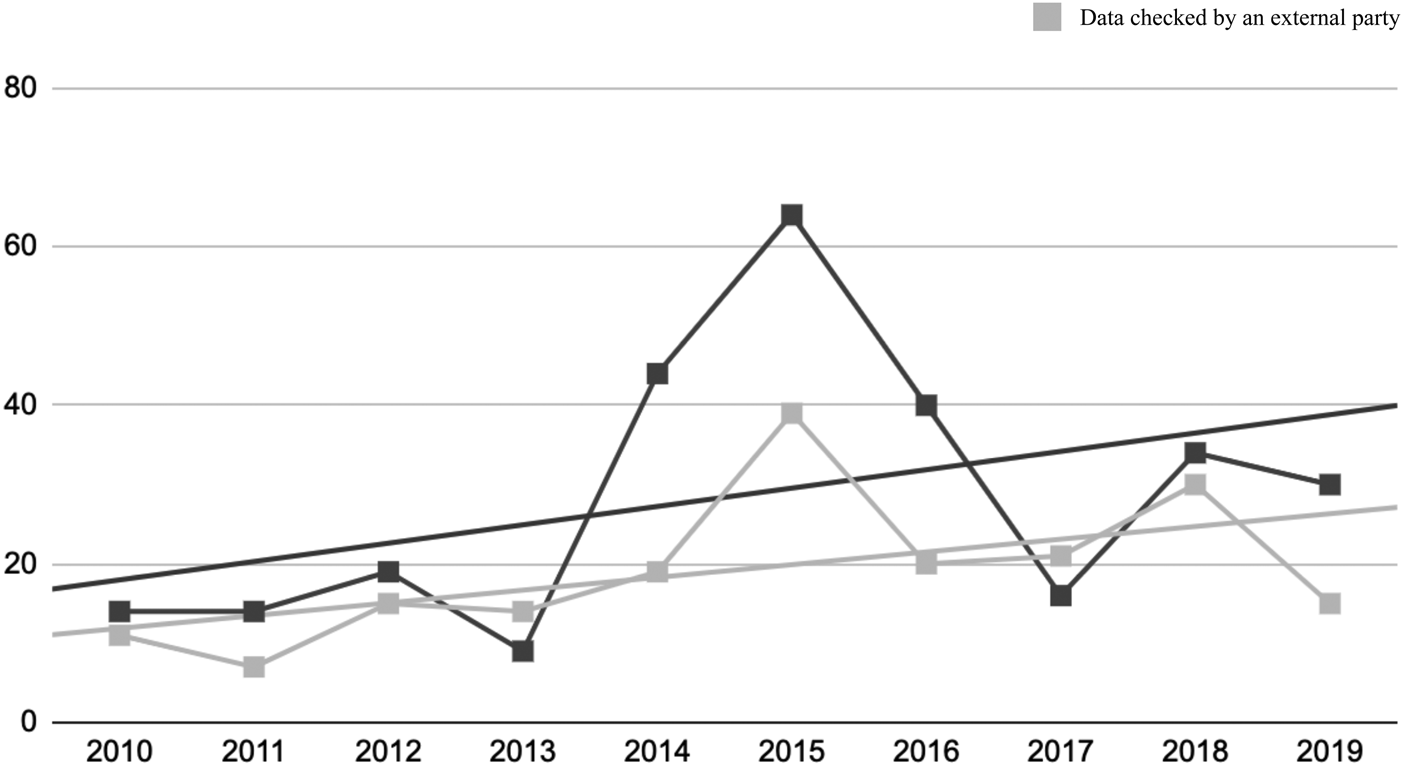

A 30-year time lag separates Ganzhou from Foshan's history of experimental national firsts, and early experiments leaned heavily on patriotic language borrowed from central policymakers.Footnote 106 Unlike Foshan, which saw a slow, steady increase in experimentation, Ganzhou's experimental policymaking has been erratic, dropping sharply after 2015, the year Party secretary Shi Wenqing 史文清 left office. While Guangdong is well developed, Jiangxi lags behind the rest of the country and the gap was still widening in 2012.Footnote 107 Ganzhou is typical of an “underdeveloped region”Footnote 108 but one of several powerful subregions challenging provincial dominance over policymaking.Footnote 109

In 2012, Shi Wenqing bypassed provincial authorities and petitioned central leaders to permit the region to initiate a new policy in a move never attempted before in Jiangxi: he proposed using tax incentives to attract FDI. According to the section chief of the Ganzhou IPA: “Between 2012 and 2013, Ganzhou, the core of the former Central Soviet Area, made a special report to national leaders to request [approval for] the [revitalization and development of Gannan and other former soviet areas].”Footnote 110 The policy was one of many under Shi's flagship experiment to “revitalize” southern Jiangxi, which was approved by the State Council in June 2012 and aimed at encouraging innovation and pilot projects. During the uncertainty of 2013, the only experiments initiated in Ganzhou were those related to this flagship experiment (Figure 4). In 2014–2015, almost 50 per cent of all experimental regulations cited it. When Shi left office at the end of 2015, mentions of his experiment dropped.

Figure 4: Experimentation as a % of All Official Documents (Ganzhou)

Shi reduced the risk of failure and punishment by leveraging guanxi within the Communist Youth League and the General Office of the NPC Standing Committee.Footnote 111 Appealing for central patronage reduces risk and ensures central recognition. Shi's experiment, which, like that of his predecessor, was wrapped in revolutionary-era patriotism, sought to use FDI to develop Ganzhou:

Economic development … in southern Jiangxi is lagging … descendants of the Red Army and revolutionary martyrs live in embarrassing conditions … The [policy] is not only a major economic task but also a political one. [Ganzhou must] improve the level of opening up to the outside world, transform and upgrade foreign trade and export.Footnote 112

Preferential tax policies (shuishou youhui 税收优惠) are neither new nor unusual and have been used across China for decades to encourage foreign investors to fulfil central development priorities.Footnote 113 Location-specific tax incentives channel FDI into areas in need of development or else attract companies in specific industries.Footnote 114 Shi's experiment was a learned innovation, not a newly generated national first, and therefore was less risky. Even though Ganzhou is a central-region city, Shi's experiment repurposed a national policy intended to develop the western region (xibu da kaifa 西部大开发) in order to gain support for his flagship experiment: “It is the only region in East China (hua dong 华东) that implements the taxation policy for western development.”Footnote 115

Coupled with Shi's direct petition for central approval, the adoption of a learned policy is a more cautious approach than Foshan's nationally unprecedented experiment, which was initiated with only tacit approval. Although Shi “punched above the weight of a typical city-level leader,”Footnote 116 he was successful within the confines of hierarchical command and oversight, achieving clearly measurable results. As a leading official in the Ganzhou IPA remarked: “Since the 13th Five-Year Plan, Ganzhou has maintained rapid growth and momentum in attracting foreign investment, growing at an annual rate of 10.08 per cent, reaching US$2.012 billion in 2019, ranking first in the province.”Footnote 117

Shi is a textbook “strategic autocrat” in that he is motivated by reward and promotion rather than a genuine desire for change, and is highly sensitive to personal risk.Footnote 118 As the Xi administration seeks to curb rather than encourage local autonomy, strategic autocrats only experiment in compliance with central directives; if none existed, officials like Shi would not experiment under Xi.Footnote 119 Yet Shi not only experimented, he also tailored his presentation of this experiment to fit Xi's “good cadre” rhetoric, which demands clean, innovative cadres willing to face risk (feng xian 风险), take responsibility (zeren 责任) and constantly innovate (gexin 革新): “We must devote ourselves to … self-purification, self-improvement, self-innovation … being aware of risks and having a sense of responsibility.”Footnote 120

Shi's rapid response to Xi's “good cadre” rhetoric, initiating an experiment during the 2012–2014 slump (Figure 1), supports the argument that he is a strategic autocrat – ambitious, sensitive to risk, and hyper aware of top-level directives. Strategic autocrats like Shi not only find ways to reduce the inherent risk of experimentation – by, for example, requesting authorization before experimenting and policy learning – they also experiment in conscious compliance with Xi's order to innovate.

Like Foshan, another interesting development in the Ganzhou case is evidence of an immediate local learning effect. The provincial capital, which is Ganzhou's direct competitor, is now experimenting with its own tax incentive policies to “stabilize” FDI.Footnote 121 The “successful” experiment in Ganzhou has been expanded to a competing neighbouring city, again, directly contradicting the literature on policy experimentation before Xi.

Despite central patronage, his cautious but materially successful policy experimentation and his subsequent promotion in 2015, Shi Wenqing was placed under investigation for corruption in September 2020.Footnote 122 Successful policy experiments do not protect officials from the anti-corruption campaign. The Ganzhou case demonstrates that experimentation has continued under Xi but also that it continues despite dramatically increased risks for officials seeking to distinguish themselves as innovators.

Discussion

Despite huge differences in local conditions and the likelihood of experimentation occurring, our two cases initiated and developed policy experiments under Xi Jinping. To explain why some local officials might still experiment despite the increased risks associated with Xi's anti-corruption and (re)centralization campaigns, Lewis, Teets and Hasmath put forward personality type as the explanatory variable, arguing that “authoritarian” personality types will not experiment under Xi owing to their sensitivity to increased risk, while “entrepreneurial” types will continue to experiment regardless.Footnote 123 In our study, both the “strategic autocrat” and the “entrepreneurial” personality types initiated policy experiments. This does not challenge the value of personality types in understanding experimental behaviour in China, especially considering the drop in experimentation after Shi left office; however, it does point to the existence of a central directive mandating experimentation. Strategic autocrats will only experiment if doing so complies with central directives and, as Shi Wenqing's own speeches show, local officials explicitly cite Xi's repeated demand for constant innovation while experimenting.

Another interesting similarity between these two contrasting cases is the emergence of new coping mechanisms used to reduce the inherent risk of experimentation. Ganzhou's cautious approach suggests that learning from elsewhere might become a more common method of experimentation. Although policy learning itself is nothing new, previous studies of Chinese experimentation saw no immediate local learning. Both our cases show evidence of a possible local learning mode of experimentation wherein competing governments seek to emulate the successful experiments of their neighbours. This contradicts previous observations that Chinese policy experiments tend not to emulate innovations adopted by neighbouring locations.Footnote 124 It also suggests local officials could become less interested in gaining recognition as first movers and more likely to initiate a learned experiment from nearby, thereby minimizing the risk of failure while still demonstrating their willingness to experiment.

An interesting difference is that Ganzhou's experimentation mode did not follow the traditional, pre-Xi model that Foshan seems largely to adhere to; instead, a new coping mechanism developed. By requesting authorization before initiating his experiment, Shi reduced risk and ensured central recognition should the experiment succeed. This could also suggest that while those regions with a history of experimentation may feel more confident taking innovative steps before officially requesting permission to do so, regions without this experience may be more inclined towards “the policymaking mode of the Xi Jinping era” by explicitly requesting authorization to both mitigate the risk of failure and ensure recognition.Footnote 125

The biggest change discussed in both the extant literature and demonstrated in our two cases is that experimentation is no longer optional: it is obligatory. This has been made possible by the centre's increased steering capacity, which forces inexperienced regions that would be very unlikely to experiment to comply with Xi's administrative command to do so. For its part, increased steering capacity does not necessarily coincide with Xi Jinping coming to power. Although new steering instruments such as the anti-corruption and (re)centralization campaigns have been introduced under his leadership, others were developed by previous administrations. Some changes made under Xi are part of longer-term trends in which aspects of decentralized policymaking were already being (re)centralized – for example, local budget reforms. The combination of potentially contradictory commands – that local governance must be clean and innovative – has created a novel situation wherein pressure to experiment no longer allows local governments not to experiment. Having observed the response to these changes in two case studies, it is possible to make a few observations about how policy experimentation may have changed under Xi Jinping across the country, although more research is certainly needed to substantiate the claims that we derive from our findings.

The political risks associated with experimentation are higher than ever. In both cases, despite differences in local conditions, officials fell victim to career freezing. In Foshan, those charged with implementing the experiment simply failed to reach targets or produce new innovations, while the Ganzhou case involved corruption. Interestingly, in both cases, individuals who were “punished” had previously been promoted for their involvement in experimental policies. However, experimentation is still occurring, which suggests that the political risk of not experimenting is higher than the increased risk involved in experimenting, an assertion further supported by explicit references to the direct administrative command to experiment in Shi Wenqing's speeches. However, to provide further support for this assertion, it is necessary to study more recent policy experiments, experiments initiated by older “bureaucratic autocrats,” cases where local leaders did not initiate experiments, and experiments in other policy fields.Footnote 126

The pay-out from successful experimentation in both cases appears decidedly short term, both in terms of personal benefits for policymakers and the creation of new, innovative solutions to the challenge of attracting FDI. Neither experiment contributed to central policymaking in a genuinely novel or useful way. Central FDI policies, such as the slight liberalization offered in the new Foreign Investment Law promulgated in January 2020, are also failing to appease international investors.Footnote 127

Conclusion

We can conclude that experimental policymaking under Xi may have seen a reduction in quality, if not quantity. Even if experimentation is occurring in regions that previously would have been very unlikely to experiment, the actual scope of those experiments may be limited to emulation rather than innovation.

This begs the question of what experimentation under pressure means in terms of governance quality. Does it represent a genuine search for innovative policy instruments or just a performative response to top-down steering? The answer is: it varies. Our analysis of official regulations showed that many experiments which began as trials, pilots and demonstrations were deemed successful enough to later become regular policies. However, in 2021, despite referring to pilots as the “most effective” policymaking method, Xi criticized performative “show-style” (xiu shi 秀式) experimentation and “grandstanding” (huazhongquchong 哗众取宠).Footnote 128 It was not our purpose to judge the success of local policy experiments; however, this is clearly a valuable point of departure for future research.

Although generalizing the results of these comparative case studies may prove difficult, this article does justify further work to refine the experimentation under pressure concept and thereby gain a better understanding of how different sources of pressure converge to define the behaviour of local officials across China and across different policy fields. The emergence of similar coping mechanisms in this article's case studies also justifies further research on whether experimentation under pressure leads to requesting authorization and a local learning mode in other regions and policy fields.

Ultimately, several unfortunate events limit this research's generalizability. First, since Shi Wenqing was accused of corruption in December 2019, local officials were unwilling to discuss his policies or situation. Second, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in January 2020 made contacting government officials exceptionally difficult. It remains to be seen to what extent experimentation under pressure can be researched on-site in the future.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Appendix

Using the PKU Law database, we recorded every “official (administrative) regulation” (defang guifanxing wenjian 地方规范性文件) issued by the Municipal People's Government between 2010 and 2019 in which a “trial” (shixing 试行), “demonstration” (shifan 示范), new “model” (moshi 模式) or “pilot” (shidian 试点) was authorized, called for or built upon.Footnote 129 If slightly different terms were used to describe an experiment, i.e. prove/demonstrate (lunzheng 论证), the document was recorded only when contextually relevant. We also recorded every document citing “innovation” (chuangxin 创新), regardless of context.

PKU's database only offers a limited preview (50 per cent) of documents, in some cases only the regulation title. Here, we looked up the regulation via the city's government website. We then had a third party perform the same process for Foshan and Ganzhou and two further cases (Wuhan, Shanghai). Our results remained consistent.

Abbey S. Heffer is a PhD candidate at the University of Tübingen. She researches modern authoritarianism, local policymaking and central–local relations in China.

Gunter Schubert is chair professor of greater China studies at the University of Tübingen. He specializes in local governance and policy implementation in China, cross-Strait political economy and Taiwan domestic politics.