IntroductionFootnote 1

No single body of primary sources in the literary heritage of sub-Saharan Africa has attracted as much attention or attained as much celebrity during the past 25 years as the fabled Arabic manuscripts of Timbuktu.Footnote 2 The Road to Timbuktu, the film series produced by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. featured them,Footnote 3 international conferences and major books focused on them,Footnote 4 the Tombouctou Manuscripts Project was launched in 2003, and the South Africa-Mali Project: Timbuktu Manuscripts was dedicated to their recovery and documentation.Footnote 5 With the Islamist intervention in Timbuktu in 2012 came the threat of their destruction and widespread international press coverage. Two books have been written on that episode and the heroic efforts made to safeguard them.Footnote 6 All told, during the past quarter-century, multiple major grants totaling millions of dollars from Europe, the Gulf states, Iran, and the U.S. have been generated to catalogue and preserve Timbuktu’s literary heritage. This notoriety, at the expense of similar manuscript libraries as near as Djenné or further afield in neighboring southern Mauritania and Niger, has triggered some justified grumbling from students of other repositories of Islamic learning in West Africa. But only one site carries the quasi-mystical appellation of “Timbuktu,” that has played so large in the European imagination for centuries. Nor have other sites been blessed with comparable cultural entrepreneurs who have been so effective in linking the story of Timbuktu’s scholarly past with twentieth-century manuscript writing. Indeed, the city’s three sixteenth-century scholarly lineages, upon which most of its historic fame rests, are well documented, but even better advertised (and pitched to funding agencies) are the vast numbers of Arabic manuscripts in and around Timbuktu today. A somewhat romanticized medieval scholarly past has long been assumed to be connected to the current manuscripts of Timbuktu; recent cataloguing of contemporary manuscript libraries there shows little if any link to that storied past.

Oddly, with all the attention they have received, and despite cataloguing efforts at the national manuscript collection in Timbuktu that dates back at least thirty years, the actual contents of the private libraries in Timbuktu remain largely unknown.Footnote 7 Much ink has been expended on claims about the numbers of manuscripts in and around Timbuktu and projections of manuscripts waiting to be discovered.Footnote 8 Almost no attention has been paid to what is in the manuscripts, what function or knowledge practice they served, and the levels and kinds of learning, teaching, and scholarship they represent. This can be attributed in part to the wonder and mystique that surrounds all manuscript libraries: they tend to be inaccessible and opaque, and private manuscript libraries in the southern Sahara are not immune from this. Contributing to our ignorance in West Africa, until recently, has been the absence of comparative data against which library holdings can be evaluated. In the absence of such comparisons, all authors, all manuscripts, all libraries are unique; little wonder that the Timbuktu libraries and manuscripts have attracted such attention from film producers. What is unique or original or commonplace or mundane can only be known by comparing works and libraries across the large sweep of West Africa’s manuscript culture.

The SAVAMA-DCI Libraries and Comparative Data from the West African Arabic Manuscript Database

Today, thanks to an ambitious project undertaken by a Malian consortium of private libraries, the Sauvegarde et Valorisation des Manuscrits pour la Défense de la Culture Islamique, (SAVAMA-DCI), we can begin to answer: What’s in the manuscripts of Timbuktu? Admittedly, SAVAMA-DCI represents only 35 of the private libraries in Timbuktu, but the volume of manuscripts inventoried in this project makes it a plausible cross-section of that city’s manuscript culture. The manuscripts number nearly 350,000 and SAVAMA-DCI, in collaboration with The Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures, University of Hamburg (CSMC), and the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML), St. John’s University, St. Cloud Minnesota, have been recording all of the manuscripts. Those inventories, from 35 member libraries, have been compiled during the past five years. In 2018, the SAVAMA-DCI inventories were made available to the University of California Berkeley West African Arabic Manuscript Database (WAAMD) and all those records are now available at the WAAMD site (https://waamd.lib.berkeley.edu/).Footnote 9 The analysis that follows comes from preparing the SAVAMA-DCI data for WAAMD, where 31 of the 35 SAVAMA inventories can now be found. For the first time, we can compare this cross-section of the manuscripts of Timbuktu with holdings in a dozen other West African public and private libraries. Although the roughly 20,000 SAVAMA-DCI records that contain author information make up only about 7 percent of the Timbuktu manuscripts inventoried, the number of records provides a statistically valid sample from which tentative conclusions can be drawn.

According to its founder, Abdel Kader Haidara, the idea of the SAVAMA-DCI consortium dates from 1991 or 1996, and the construction of a building to house private collections in Timbuktu began in 1999, then was renovated and expanded in 2005, and again in 2007, each with new infusions of external financial aid.Footnote 10 SAVAMA-DCI does not include the national collection at IHERIAB, noted above, nor does it include at least two other, important private libraries there: The Fondo Kati and Imam Assuyuti Library.Footnote 11 But the SAVAMA-DCI library inventories do represent the largest number of private libraries from a single locale in West Africa that have yet been accessible to researchers. And these are the same libraries that have been at the core of “marketing” the Timbuktu libraries for external support to preserve and catalogue Timbuktu’s manuscript culture during the past 25 years. The SAVAMA-DCI inventories are comprehensive compilations of all written material uncovered in the participating libraries, and this sets them apart from most of the other libraries accessible through WAAMD. With two exceptions, all previous library records entered in WAAMD were selective: previous libraries entered in the database have privileged manuscripts in the Islamic disciplines written by local or regional authorities and classical works.Footnote 12 Ephemera, the one and two folio items copied from manuscripts, which I have called “study sheets” below, some with identifiable authors, others with no known author, were largely ignored in most of the WAAMD collections.Footnote 13 Similarly, short therapeutic and prophylactic formulae in the esoteric sciences lacking an author attribution, like talismans and other letter, word, or numeric devices written for their predictive value or to resolve personal problems, were largely ignored by cataloguers. WAAMD, from the outset, has conscientiously replicated all records from the collections included, but in doing this it has also been held hostage to the judgement of their cataloguers on what constitutes a “manuscript.” This has generally resulted in privileging manuscripts with known authors and manuscripts that fall within the classic corpus of the Islamic sciences. Manuscripts with “author unknown” regularly appear in catalogues that make up the WAAMD listings, but prior to the SAVAMA-DCI inventories there was no collection in WAAMD that listed more than 20 percent of the contents of a library as works by “unknown author.” In contrast, the inventories in the SAVAMA-DCI project include a much higher number of unknown authors, typically 90–95 percent, including many one and two folio items lacking in searchable data points, i.e. records with no author, an attributed title, and subject identification that describes a work’s affect rather than its content (discussed below).

The total number of items inventoried across the 35 SAVAMA-DCI libraries is 348,531; about 7 percent of that number, or 25,000 have attributed authors, many of whom are repeated within and across inventories.Footnote 14 About two-thirds of those authors’ names can be found in other WAAMD collections. Among the new names to the database, roughly half come from correspondence (names of letter writers as well as letter recipients are noted in WAAMD records), and the other half are new names, mainly local authors. This includes authors who are identified only by a single name (“Muhammad” or “Ahmad”), and who may only be fully known at some future date when script-recognition technologies can be applied to the documents. Similarly, more sophisticated technologies and/or methods of cataloguing will be required to tap the slightly over 300,000 items that are one and two folios in length, lacking authors, and with attributed titles. These one and two folio works make up 75 percent of the total items inventoried in the SAVAMA libraries, and they can be found in their original spreadsheet form for each library, accessible at a link found in the library’s description under the WAAMD tab “Manuscript Collections included.” There, readers can find the original entries, alphabetized by attributed titles (the most descriptive part of the entries). Longer works, exceeding two folios but also lacking author attribution, have been entered in WAAMD (about 33,000 records across all libraries). These longer works are the most likely to be identified by author and/or title when digital copies become available through the HMML project.

Across all the SAVAMA inventories there are approximately 180 unique author names, after duplicates are eliminated. That number does not include correspondence (there may be as many as 2,000 unique author names in letters), but it does include many incomplete names.Footnote 15 If we assume that the most frequently found author names are indicators of the core of a scholastic tradition, there are 55 authors whose works appear in at least half of the 31 libraries surveyed here.Footnote 16 Those authors are listed in Appendix A, where they are compared with all ninety SAVAMA authors who also appear in the Hall and Stewart “core curriculum” analysis of the most frequently found authors and texts across West Africa.Footnote 17

Hall and Stewart’s “Core Curriculum” methodology suggests that commonly found authors and texts across multiple libraries point to the probability that they were central to instruction and learning. Its corollary is that the absence or infrequency of an author or a subject implies work that was not part of the scholarly corpus. The “core curriculum” analysis was based on over eighty private library holdings across West Africa and roughly 21,000 manuscripts that had been entered in the WAAMD prior to 2011. We found 223 titles repeated in adequate numbers and widely distributed from the Atlantic to Lake Chad to permit us to tag them as West Africa’s historic “core curriculum.” The SAVAMA library inventories provide us with a rare opportunity to conduct a similar analysis since, unlike the sampling technique devised for the “core curriculum” analysis (based on library inventories that were biased in favor of the classical canon), the comprehensive inventories of the Timbuktu libraries permit a survey of all extant authored work in these libraries.Footnote 18 Thanks to the input protocol for the SAVAMA inventories, each time an author’s writing is identified, it is listed as a separate record, whether a single folio, a portion of the work, or a complete manuscript. It is well-known that manuscript libraries commonly contain portions of works, and that manuscripts were acquired both as complete works as well as in sections or chapters.

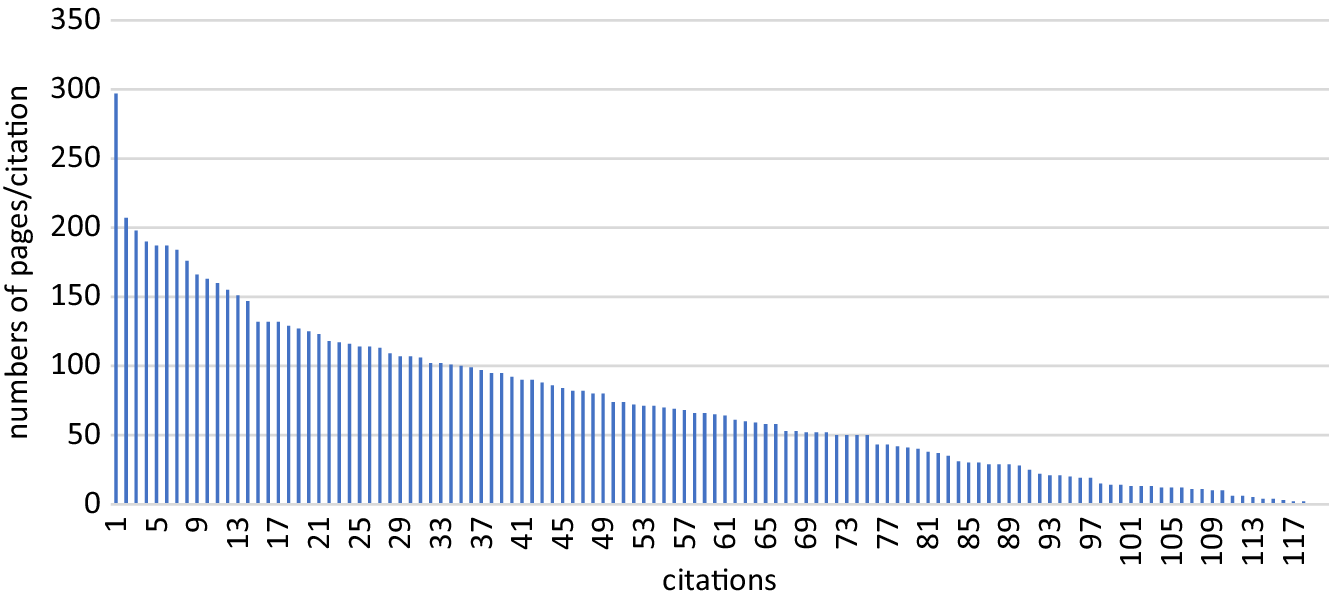

Clearly, from their small numbers of pages, some of the SAVAMA entries refer to segments of larger works. But many SAVAMA inventories also include what we are calling “study sheets,” each one catalogued as a separate manuscript. For example, Muḥammad b. Yūsuf al-Ḥasanī al-Sanūsī’s work on theology, commonly known under the titles `Aqīdat ahl al-tawḥīd al-ṣughrā and al-`Aqīdat al- ṣughrā and Um al-Barāhaīn, is found in 27 of the 31 SAVAMA libraries.Footnote 19 In them, it is listed 513 times (the three titles also appear at least 111 times elsewhere in the WAAMD database). The length of those complete works in manuscript form in WAAMD records varies, but is always more than fifteen folios. In the 513 SAVAMA citations, only 25 manuscripts meet or exceed that 15-folio threshold. Clearly, fewer than 5 percent of all SAVAMA citations of al-Sanūsī refer to a manuscript that may be his complete work. More than 90 percent of the “copies” of Sanūsī are what I have hypothesized to be “study-sheets,” less than 15 folios in length. Figure 1 captures the number of pages per copy of al-Sanūsī’s theology found in a single library.

Figure 1. Mas`ud b. Abi Bakr Library, 53 citations to al-Sanusī’s theology.

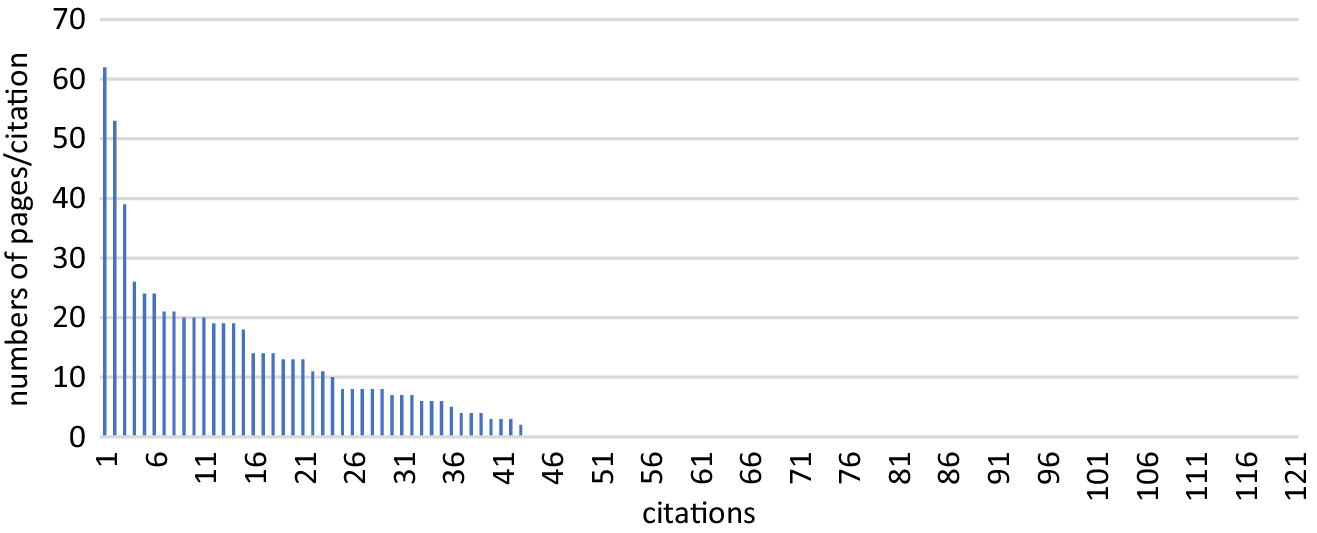

Another example is the famous devotional work on the Prophet by Muḥammad b. Sulaymān b. Abī Bakr al-Jazūlī al-Taghtīnī al-Simlālī, Dalā’il al-khayrāt, cited 521 times in thirty SAVAMA libraries (Figure 2). Fifteen of those 521 records exceed 175 pages, which, judging from the length of copies in WAAMD from elsewhere in West Africa, may be complete or nearly complete works. However, 506 of those citations appear to be fragments of the work, half of them (245) under thirty pages and likely to contain less than 10 percent of the work.

Figure 2. Abu Bakr b. Sa’id Library, 118 citations to al-Jazῡlī’s Dalā’il al-khayrāt.

Figure 3 illustrates the number of pages in 43 copies of al-Akhdarī’s work on religious duties in a single library.

Figure 3. Infa Yatara Library, 43 citations of al-Akhdarī’s work on religious duties.

These exhaustive listings in SAVAMA inventories in which each page of an identifiable work is recorded as a separate manuscript result in some oddly lopsided data on the importance of some authors as well as some very inflated numbers of manuscripts. They also must raise questions about the Hall and Stewart methodology for determining widely studied texts in the absence of page numbers/copies cited. But they do document authors and works that were evidently well studied in twentieth-century Timbuktu. The ratios of the number of “study-sheets” vs. complete works cited here for al-Sanūsī, al-Jazῡlī, and al-Akhdarī is typical for the frequently cited authors. More than 90 percent of the copies of classical works listed in SAVAMA inventories are, in fact, fragments, many very small fragments, of a work. My hypothesis that the many very brief “manuscripts” in the canon were, in fact, “study sheets” can be tested when digital copies become available. Which segments of works are found on these sheets, as well as the paper on which they are written, will also be revealing, since the availability of inexpensive paper in the twentieth century may explain their profusion. In short, the frequency of an author being mentioned in these records in the 31 libraries appears to tell us only that a writer was studied, but it also may indicate his relative importance to scholarship in recent times.

It has been noted that after duplicate names, correspondence, and unidentified partial names are eliminated, the 31 SAVAMA library inventories list just under 180 unique authors; 55 of them are found in at least half of the libraries. Three-quarters of them also appear in the Hall and Stewart “core curriculum.” Appendix A summarizes those authors and works that appear in the “Core Curriculum,” as well as the authors and works not in the “Core Curriculum” but common to half of the libraries. Interestingly, most of the authors who do not appear in the Hall and Stewart analysis are only found in catalogues dealing with the Niger Bend region and Northern Nigeria.Footnote 20 These seem to include some writers whose names may be conflated with classical authorities or who are also known (and have been inventoried) by local interpolations of their names. The anomaly of their unique appearance in the Segou/Kano/SAVAMA inventories (and nowhere else in West Africa) suggests the need to examine this handful of author attributions more closely.

A correlation between classical authorities represented in the Timbuktu libraries and the “Core Curriculum” found across West Africa might be expected. But on closer inspection, the subject matter emphasized in the SAVAMA inventories does differ in significant ways from writing and teaching reflected in other libraries in WAAMD. Table 1 presents very rough ratios of subjects compared across the “Core Curriculum,” SAVAMA libraries (based on 67 of the most frequently cited authors in 31 libraries across 20,000 SAVAMA records), and, for comparison, the original 1991 Timbuktu handlist (all 4,664 records in WAAMD), and the `Umarian, Segou library (4,138 records in WAAMD inclusive of 1,903 unknown authors).

Table 1. Comparison of subject matter in select West African collections.

Comparison of Subject Matter in Select West African Collections

A careful comparison of these subject classifications, documented by different cataloguers, leads one to understand the wisdom of the decision in some collections to not try to classify manuscript subjects. There are few immutable rules for the inclusion and exclusion of material in the Islamic disciplines, although Arabic language and Qur’an might be cited as two of the less ambiguous subjects. Even jurisprudence is fungible insofar as a subject like “religious duties” (of outsized importance in the SAVAMA inventories) might be as correctly viewed as part of religious practice (ergo, labeled under “Belief”) as a matter of jurisprudence. Thus, the differences between high and low percentages of works on Belief/Theology in the chart above are likely due to the inclusion/exclusion of writing on religious duties. Writing on the biography, attributes, and characteristics of the Prophet Muhammad is commonly fused in the SAVAMA records with Prophetic love literature (described as “devotional” literature in WAAMD), and sometimes Hadith. The SAVAMA inventories also contain an elevated number of records dealing with conduct and spiritual counsel in comparison to the other collections in this chart. In short, any subject classification system must be approached with caution.Footnote 21 That said, there are remarkable parallels across these collections as well as differences that may reflect variants within West African intellectual history.

One caveat to understanding the historical depth of these libraries: There is no data on the age of manuscripts in the SAVAMA-DCI inventories. A frequent description under “manuscript condition” indicates “modern script,” which suggests writing within the past 50–75 years, but this and the occasional reference to a “very old” work are the only clues to the age of manuscripts. Thus, an important measure of any continuity of today’s libraries with Timbuktu’s “golden age” in the seventeenth century is missing. That continuity might be implied if we found copies of work that date from that era, but, alas, they are rare.Footnote 22 The near total absence of seventeenth-century writing, the large number of “study sheets” described above, and the inventories all suggest that the SAVAMA libraries, with a very few exceptions, are not ancient, but rather of twentieth-century provenance.Footnote 23

What are the Distinguishing Features of the SAVAMA-DCI Manuscripts?

There are several observations that can be made about the subject matter in SAVAMA inventories that do reflect the intellectual baggage in those library holdings. Most striking is apparent confirmation of a note that first appeared in my “Calibrating the Scholarship of Timbuktu.”Footnote 24 There, I hypothesized that the near absence of writing on Arabic grammar in seventeenth-century Timbuktu might be explained by a culture in which the teaching of Arabic was monopolized by select scholarly lineages.Footnote 25 The paucity of works on grammar demonstrated by the negligible proportion (only 2 percent) of the content of SAVAMA libraries that include either Ibn Mālik’s al-Alfiyya, or Ibn Ājurrūm’s al-Muqaddima al-ājarrῡmiyya Footnote 26 point to the likelihood that Arabic syntax was still not widely studied in these twentieth-century libraries, or not studied from the classic authorities. Arabic study even in the Golden Age of Timbuktu was likely a subject guarded by a small class of literati; in Goody’s description, it was an oligoliterate culture.Footnote 27 Reference below to the widespread presence of pre-Islamic poets in these libraries suggests the intriguing possibility that applications of Arabic grammar found in early Islamic prosody have supplemented or replaced reliance on classical teaching on syntax. Insofar as al-Ḥarīrī and pre-Islamic prosody may have served this function, it would argue for a contribution this literature may make to our understanding of the evolution of literacy.

There is no shortage of copies of the Qur’an or sections of the Holy Book in SAVAMA inventories, and the treatment of specific verses and their efficacy in resolving personal problems is a major theme in the esoteric sciences. But at first glance there is a lacuna in the SAVAMA inventories in Qur’anic commentaries/tafsīr and recitation/tajwīd, although a handful of works identified as Qur’anic knowledge/`ilm al-Qur’ān may contain such sub-sets in the discipline of Qur’anic sciences.Footnote 28 The lack of works on recitation, like the relatively few grammars, points to the likelihood that Qur’anic recitation was left to the specialists and was not a widely studied subject. The correct pronunciation of words and styles of recitation have always been a fundamental take-off point in Islamic education, which makes the absence of this subject even more curious in the SAVAMA inventories. The dearth of formal tafsīr/Qur’anic exegesis in some quarters in West Africa has been explained as an artifact of inadequate libraries to research and support interpretation of the Holy Book.Footnote 29 Yet as Bondarev has demonstrated in annotated copies of the Qur’an from early Bornu, a thorough examination of older Qur’anic texts may reveal past access to tafsīrs that are no longer extant in these collections. Footnote 30 Aside from one exegesis by `Abd al-Raḥmān b. Abī Bakr al-Suyūṭī, found in two libraries, no other Qur’anic commentaries appear among the most frequently found authors in the SAVAMA inventories.Footnote 31 This may be a genre more frequently found in `ajamī writing, as Bondarev has observed and Tal Tamari has described in Bamana texts, but the near absence of classical authorities remains puzzling.Footnote 32 As with the query into the absence of standard grammars above, the source and form of most widely consulted tafsīr may not have been the “free-standing” texts devoted to this but rather in marginalia (not well documented in these inventories) or unauthored pages addressing the efficacy of particular sῡra in the esoteric sciences.

A second observation from the “Calibrating” analysis, also confirmed by the SAVAMA holdings, is the absence of any indication of obvious tension between local, customary law and the shari’a. Elsewhere in West Africa, this is a barometer for signaling efforts to integrate the shari’a into local usage. Typically, one finds it expressed in “problems” and “answers” in the juridical literature, or commentaries in uṣῡl al-fiqh. The SAVAMA inventories are striking for the near absence of this genre of legal writing. Associated with this is also the study of logic, through which skills are acquired to interrogate, parse, and argue legal precedent. Admittedly, the study of logic – where one finds it in the Mauritanian maḥaẓra tradition – went against the grain of Traditionalists, who took pains to avoid the discipline. But it was widespread enough in West Africa that it is unusual that only two of the 31 SAVAMA inventories list any manuscripts on logic (and those sans author and title).Footnote 33

The fact that the SAVAMA inventories include less than half the writing in jurisprudence that is found in other West African libraries is distinctive. One possible explanation, noted above, is that the libraries surveyed here are not “historic” centers of learning with pre-twentieth-century roots. Rather, they reflect twentieth-century scholarship when much of the pre-colonial legal writing had been compromised by colonial administrative law. This is the conclusion I arrived at when comparing two substantial bodies of legal writing in southern Mauritania from the mid-nineteenth and from the mid-twentieth centuries in the same village and written by jurists within the same family, three generations apart.Footnote 34 The “bread-and-butter” economic issues from pre-colonial times had largely been replaced 100 years later with fatāwā on religious matters; the well-born and well-connected had evidently found manipulating French legal code, certainly in economic matters, to be more in their interest than rulings according to the shari’a. Something like this may explain the dearth of legal literature in these libraries where the principal applications of the shari’a appear to have been in matters defining religious duties, itself a focus for much historic legal writing and studying in West Africa. What is striking, not unlike the dearth of legal writing altogether, is the near total absence of local authorities who authored commentaries, summations, or condensations of legal writing on that one dominant concern: religious duties. Perhaps, as with Qur’anic exegesis, this is where an examination of `ajamī texts will reveal local commentaries and explanations of classical writing.

For libraries that are not strong in the classical literature, it might be surprising to find the near-uniform attention given in two-thirds of these libraries to pre-Islamic poetry and the classic authority on prosody, Qāsim b. `Alī b. Muḥammad al-Ḥarīrī.Footnote 35 Unlike many of the other classic authorities, 75 percent of the al-Ḥarīrī manuscripts appear (by their length) to be substantial if not complete texts of his Maqāmāt. Of equal importance are the number of pre-Islamic poets and poets from the early years like Shanfara `Amr b. Mālik al-Azdī,Footnote 36 Zuhayr b. Abī Sulama al-Muzanī,Footnote 37 Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan b. Durayd al-Azdī,Footnote 38 Imru’ al-Qays b. Ḥujr b. al-Ḥārith al-Kindī,Footnote 39 and Ḥasan b. `Alī al-Iṣfahānī al-Ṭughrā’ī.Footnote 40 Their significance lies in the likelihood that they provided the method and template for adapting Arabic script to poetry in African languages and/or adapting poetry in African languages to classical Arabic forms. It may also provide a clue to an application of these texts for the study of grammar in lieu of classical texts. This relation between al-Ḥarīrī, the pre-Islamic poets, and templates for `ajamī writing awaits research, but something similar is found in Hassaniyya poetry, and Tal Tamari has described the influence of al- Ḥarīrī on Bambara prosody.Footnote 41 A similar methodology may be anticipated in adapting Arabic to other African languages, and, if demonstrated, the strong presence of these authorities across these libraries suggests their importance in fostering `ajamī writing. The WAAMD records indicate 213 documents in `ajamī from the SAVAMA inventories, which does not include the large number of short items that are only available on their original spreadsheets in WAAMD. Nor is it inclusive of the most common use of `ajamī, the insertion of translations or explanations of Arabic words in the marginalia of texts. `Ajamī is found in about 11 percent of the SAVAMA entries in WAAMD; across all WAAMD records, `ajamī ranges between 10–15 percent.Footnote 42 The field of `ajami studies and the notion of the “`ajamization of Islam” in West Africa is relatively new, recently summarized by Fallou Ngom.Footnote 43 At Hamburg’s CSMS, Dmitry Bondarev is directing a long-term project focused on documenting and exploring `ajami materials in the SAVAMA-DCI manuscripts reviewed here.

The SAVAMA-DCI inventories contain more correspondence than any other collection in WAAMD. Over 7,000 letters provide insight into quotidian affairs, from social relations and commerce to legal opinions.Footnote 44 The two most frequently cited subjects are social greetings and commercial affairs; if, as suggested above, these libraries represent mainly twentieth-century holdings, bodies of this correspondence should offer a unique vantage point on colonial occupation and the colonial economy from the point of view of the literati. Individual libraries tend to be dominated by their custodians’ correspondence (or their custodians’ forebearers letters), but names of particularly prolific letter writers reappear across libraries often enough to track the affairs of a few of the correspondents. The much larger number of letter writers than scholars, evident in this sampling, invites inquiry into the training for letter writing supported by these libraries that, as the volume of letters suggests, must have been an important teaching subject.Footnote 45

The relatively heavy concentration of texts on Belief/tawhīd in SAVAMA inventories deserves comment. This one body of writing not only features more of the “Core Curriculum” texts than any other category, but when joined with devotional material accounts for three-quarters of all the texts that are new to the “Core Curriculum” compilation. If there is a center to the Islamic culture in this Timbuktu literature it would be this – theology and spiritual instruction – and that contrasts with typical foci (that vary) in other WAAMD libraries on jurisprudence, language and literature, and the Prophet Muhammad. Why this should be the case, or if this may be a misreading of the SAVAMA inventories, will be solved by future research. Certainly, these inventories do not contain the quantity and depth of praise literature and poetry typically found in other Saharan libraries, although this may be revealed in `ajamī writing, and they are rich in Prophetic love literature. The intellectual ingenuity on display here is not to be found in the study, commentaries, and adaptations of classical Islamic texts but rather in adaptations of the Arabic script to African languages in `ajamī writing.

The dominant genre in the SAVAMA-DCI libraries presents a special challenge to bibliographers: the tens of thousands of short, one- and two-page items without authors, with attributed titles, and with subject matter that often specifies the affect or the efficacy of the text. This also presents one of the greatest challenges to utilizing most of the documents in these inventories. These one- and two-page items make up 75 percent of all SAVAMA inventories. At least one-quarter of all these records describe their subject matter with the terms: fawā’id (beneficial), or al-manaf`a (of benefit), or as faḍā’il (of virtue), or al-khawāṣ (special value). These are frequently items in the esoteric sciences, and their attributed titles indicate they deal with a specific sῡra, discrete branches of the esoteric sciences, specific types of devotions, conduct, ethics, or elements of belief (names of God, names of saints, etc.). For records exceeding two pages identified in this way that have been entered in WAAMD, where key words in titles made more precise content identification possible, those topics have been identified as subjects. But this has also corrupted those qualitative subject designations entered in the field. For these, students will need to consult the original subject designation assigned in the field, available on the library inventory spreadsheets at the CSMC/SAVAMA site and, for the one- and two-page items lacking authorship, at the link on WAAMD collections pages. Paul Naylor has argued that these items might best be categorized by the qualitative value assigned by cataloguers in the field.Footnote 46 There may be a typology for their categorization waiting to be formulated, based on the intersection of the texts of origin and the social context in which they found application. A team at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library is currently working on such a system of categorization of these items that will hopefully make them more accessible than they are at present.

Conclusion

The SAVAMA-DCI inventories give us the first near-comprehensive inventory of a West African manuscript culture within a circumscribed site. That the site is Timbuktu is bound to add luster to any findings, but it is, in fact, probably also typical of many urban, Islamic cultures in the twentieth century where multiple private libraries are found or have been amalgamated. The SAVAMA-DCI libraries provide a unique opening to the intellectual makeup of Islamic Africa in the twentieth century. It is therefore more profound and complicated than earlier assumptions about a seventeenth-century scholarship still alive 300 years later in the fabled manuscripts of Timbuktu. Clearly, most of these are not libraries of any great historical depth, nor do they contain much extended writing in the Islamic disciplines by local authors.

These libraries document well the fact that Timbuktu was not the center of West African Islamic scholarship that popular belief has wanted it to be. The paucity of Arabic language texts suggests an oligoliterate culture, and the absence of subjects like logic suggest legal reasoning was not a part of the limited juridical writing. Further, the lack of evidence of tension between customary law and the shari’a implies not an Islamic culture that rested on jurisprudence, but rather one where the overwhelming juridical preoccupation was with religious duties.Footnote 47 The profusion of Prophetic love literature appears to largely define this Islamic culture and is without a parallel in other WAAMD libraries. If a manuscript library can reveal the teaching and learning most valued in an Islamic culture, we must look outside the classical canon in the Islamic sciences to find the value of these manuscripts of Timbuktu. Despite the claim in much of the hype about the Timbuktu manuscripts that they are an embodiment of classical Islamic learning dating back to the sixteenth century, this is not reflected in the contents of these libraries.

What is reflected in the contents of these libraries is something far more complex and much more interesting. What the SAVAMA inventories tell us is that the importance of Timbuktu’s manuscript culture needs to be assessed in its own terms. This can begin by taking seriously the vast corpus of one- and two-page, largely twentieth-century formulas. This genre grew, in part, out of sources drawn from the classical disciplines, no doubt married to local needs. The modest number of classical sources evidenced today in these libraries ought to make the mapping of their classical roots relatively easy. This is a body of literature that may be an artifact of the relative ease of access to paper in the early twentieth century. It also suggests that inexpensive paper may have also ushered in a new way of learning in a post-lauḥ age, as well as explaining the “study sheets” noted above.Footnote 48

Perhaps most significant is the evidence of al-Ḥarīrī and the pre and early Islamic poets across these libraries and the possible link between that literature and adaptations of classical meter to `ajamī verse. In brief: This body of literature opens questions and calls for a new thinking about the intellectual history of Timbuktu, not constrained by an Islamic canon but innovative and original in its applications of an Arabic literary past to the formulations of an African literature in Arabic script.

Appendix A

Core Curriculum authors/works and their frequency in SAVAMA libraries. Bold entries indicate 23 authors not present in the Core Curriculum, but found in at least three-quarters of SAVAMA libraries.Footnote 49

Qur’anic Sciences

-

• Recitation (tajwīd)

-

○ Ibn al-Barrī, al-Durar al-lawāmi` Footnote 50

-

○ Ibn Jazarī, al-Muqaddima al-jazariyya Footnote 51

-

-

• Qur’anic revelation (tanzīl) and abrogation (naskh)

-

○ Ibn Juzaī, al-Tashīl li-`ulῡm al-tanzī Footnote 52

-

-

• Exegesis (tafsīr)

-

○ al-Suyūṭī and al-Maḥalīli, Tafsīr al-Jalālayn Footnote 53

-

Arabic Language

-

• Lexicons and Lexicology

-

○ Muḥammad b. al-Mustanīr Quṭrub, Muthallath Quṭrub Footnote 54

-

○ `Abd al-`Azīz b. `Abd al-Waḥīd al-Lamṭī al-Miknasī, Sharḥ al-Mῡrith Quṭrub Footnote 55

-

-

• Morphology

-

○ Ibn Mālik, Lāmiyyat al-af`āl Footnote 56

-

○ Ibn Mālik, Tuḥfat al-mawdῡd fī ‘l-maqṣῡr wa-‘l-mamdῡd Footnote 57

-

○ Ibn Durayd, al-Maqṣῡr wa-‘l-mamdῡd Footnote 58

-

-

• Syntax

-

○ Ibn Mālik, al-Afiyya Footnote 59

-

○ Ibn Ājurrūm, al-Muqaddima al-ājarrῡmiyya Footnote 60

-

-

• Rhetoric

-

○ `Abd al-Raḥmān b. Muḥammad al-Akhdarī, al-Jawhar al-maknῡn Footnote 61

-

-

• Literature/Prosody

-

○ Qāsim b. `Alī b. Muḥammad al-Ḥarīrī, al-Maqāmāt li-‘l-Ḥarīrī Footnote 62

-

○ Shanfara `Amr b. Mālik al-Azdī, Lāmiyyat al-`arab Footnote 63

-

○ Ḥasan b. `Alī al-Iṣfahānī al-Ṭughrā’ī, Lāmiyyat al-`ajam Footnote 64

-

○ Ibn Durayd, al-Maqṣῡra Footnote 65

-

○ Imru’ al-Qays b. Ḥujr b. al-Ḥārith al-Kindī, Bānat su`ād Footnote 66

-

Prophet Muhammad

-

• Biography (sira)

-

○ `Abd al-`Azīz b. `Abd al-Waḥīd al-Lamṭī al-Miknasī, Qurrat al-abṣār Footnote 67

-

-

• Devotional Poetry

-

○ Mughalṭāy b. Qilīj b. `Abd Allāh al-Bakjarī al-Ḥikrī al-Ḥanafī, Khaṣā’iṣ al-muṣṭafā Footnote 68

-

○ Muḥammad b. Sa`īd al-Būṣīrī al-Ṣanhājī, and Muḥammad b. `Abd al-Raḥmān al-Marrākushī (sic), al-Burda [al-Kawākib al-durriyya…] Footnote 69

-

○ `Abd al-Rahman b. Yakhlaftān b. Aḥmad al-Fāzāzī, al-`Ishrīnīyāt Footnote 70

-

○ Muḥammad b. Sulaymān b. Abī Bakr al-Jazūlī al-Taghtīnī al-Simlālī, Dalā’il al-khayrāt Footnote 71

-

○ Muḥammad b. `Abd Allāh b. Sa`ād al-Fῡtī, Qaṣīda fī madḥ al-nabī Footnote 72

-

○ Ibn Naḥwī: Abū al-Faḍl Yusuf b. al-Naḥwī al-Tawzari, Qaṣīda al-munfarija Footnote 73

-

○ Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. Marzūq al-Tilimsānī, al-Qaṣīda al-marzūqiyya Footnote 74

-

○ Muḥammad b.`Abd al-`Azīz b. al-Warrāq al-Iskandarī, and Muḥammad b. `Abd al-`Azīz al-Lakhmī, Qaṣīda al-watariyya Footnote 75

-

○ Zuhayr b. Abī Sulama al-Muzanī, Bānat su`ād Footnote 76

-

○ `Umar b. Sa`īd b. `Uthmān b. al-Mukhtār al-Fūtī, Kasb al-faqīr Footnote 77

-

○ Muḥammad b. Muḥammad b. Aḥmad al-Ghazālī, al-Kanz al-a`ẓām and Ṣalāt al-kaymayā’ Footnote 78

-

○ `Uthmān b. Muḥammad Fūdī, Mukhtῡb al-ṣalāt `ala al-nabī Footnote 79

-

Hadith collections

-

-

○ Muḥammad b. Ismā`īl b. Ibrāhīm al-Bukhārī, Ṣaḥiḥ al-Bukhārī Footnote 80

-

○ Ibn al-Jazari, Ḥiṣn al-ḥaṣin Footnote 81

-

-

• Sciences of Hadith

-

○ `Abd al-Raḥīm b. al-Ḥusayn al-`Irāqī, Alfiyyat al-`Iraqī Footnote 82

-

Jurisprudence (fiqh)

-

• Uṣῡl al-fiqh

-

○ Tāj al-Dīn `Abd al-Wahhāb b. `Alī al-Subkī, Jam` al-jawāmī fī ‘l-uṣῡl Footnote 83

-

-

• Furῡ’ al-fiqh: Foundational texts

-

○ Mālik b. Anas al-Aṣbaḥī, al-Muwaṭṭa’ Footnote 84

-

▪ Sulaymān b. Khalaf b. Sa`d al-Bājī, al-Muntaqā sharḥ al-muwaṭṭa’ Footnote 85

-

-

○ Khalaf b. Abī al-Qāsim Muḥammad al-Barādhi`ī, Tahdhīb masā’il al-mudawwana Footnote 86

-

-

• Furῡ’ al-fiqh: Fiqh manuals

-

○ Ibn Abī Zayd al-Qayrawānī, al-Risāla Footnote 87

-

▪ `Alī b. Muḥammad al-Manūfī al-Shādhilī, Kifāyat al-tālib al-rabbānī li-‘l-Risāla Footnote 88

-

-

○ Khalīl b. Isḥāq al-Mālikī al-Miṣrī, Mukhtaṣar Khalīl Footnote 89

-

▪ Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm b. Khalīl al-Tatā’ī, Jawāhir al-durar Footnote 90

-

▪ `Abd al-Bāqi b. Yusuf al-Zurqānī, Sharḥ mukhtaṣar Khalīl Footnote 91

-

▪ Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan al-Bannānī al-Fāsī, Fatḥ al-rabbānī fī mā dhahala `an-hu al-Zurqānī Footnote 92

-

▪ Muḥammad b. `Abd Allāh al-Kharshī al-Mālikī al-Miṣrī, Sharḥ `alā ‘l- Mukhtaṣar Khalīl Footnote 93

-

-

○ Ibn `Āṣim al-Gharnāṭī, Tuḥfat al-ḥukkām fī nakt wa-‘l-aḥkām Footnote 94

-

▪ Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Mālikī al-Fāsī, al-Tanqāt wa’-l- aḥkām Footnote 95

-

-

○ Ibn `Askar al-Baghdādī, Irshād al-sālik ilā ashraf al-masālik Footnote 96

-

○ `Alī b. Muḥammad al-Manūfī al-Shādhilī, al-Muqaddima al-‘izziya li-‘l-jamā`a al-azhariyya Footnote 97

-

○ `Alī b. Aḥmad b. Sa`īd b. Ḥāzim al-Andalusī , Kitāb al-Ṣalāt and Du`ā’ miḥan al-rufāt Footnote 98

-

• Didactic texts

-

○ `Abd al-Raḥmān b. Muḥammad al-Akhdarī al-Th`ālbī al-Jazā’irī, Mukhtaṣar fi ‘l-ibādāt Footnote 99

-

○ Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. `Uthmān al-Mazmarī, al-`Abqarī fī naẓm sahw al-Akhdarī Footnote 100

-

○ `Abd al-Bārī al-Rifā`ī al-`Ashmāwī, al-Muqaddima al-`ashmāwiyya Footnote 101

-

-

• Al-Qawā’id al-fiqiyya

-

○ Ibn Juzay al-Gharnāṭī, Qawānin al-aḥkām Footnote 102

-

-

Belief (tawhīd)

-

○ Aḥmad b. `Abd Allāh al-Jazā’irī, Manẓῡmat al-Jazā’iriyya fī ‘l-tawḥīd Footnote 103

-

○ Khālid b. Yaḥyā b. Yῡsuf al-Jazῡlī, Natīja al-ilhām fī waṣf dar al-Islām Footnote 104

-

○ Muḥammad b. Yūsuf al-Ḥasanī al-Sanūsī, al-`Aqīda al-ṣaghīr and `Aqīda al-Sanūsī Footnote 105

-

○ Muḥammad b. `Abd al-Raḥmān b. `Alī al-Ḥawḍī, Wāsiṭa al-sālūk Footnote 106

-

○ Muḥammad b. Abῡ Bakr b. Muḥammad Baghayogho, Nazm ṣaghīrī al-Sanūsī Footnote 107

-

○ Yaḥya b. `Umar al-Qurṭubī al-Azdi, Urjūza al-waladān Footnote 108

-

○ Naṣr b. Muḥammad b. Aḥmad al-Samarqandī, Tanbīh al-ghāfilīn Footnote 109

-

○ Aḥmad b. `Abd Allāh al-Jazā’irī, al-Manẓūma al-jazā’riyya fī al-tawḥīd Footnote 110

-

○ Ibrāhīm b. Ibrāhīm b. Ḥasan al-Lāqanī, Jawahir al-tawḥīd Footnote 111

-

○ Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Maqqarī al-Tilimsānī, Ida’āt al-ḍujunna fī `aqā’id ahl al-sunna Footnote 112

-

○ Muḥammad b. al-Mukhtār b. al-A`mash al-`Alawī, Futūḥāt dhī al-raḥma fī sharḥ ida’at al-dujunna fī al-Maqqarī Footnote 113

-

○ Arbāb al-Kharṭūmī: Arbāb b. `Alī b. `Āwn b. `Amir b. Aṣbaḥ al-Kharṭūmī, al-Jawāhir al-ḥisān fi taḥqīq ma’rifat arkān al-imān Footnote 114

-

○ `Abd al-Wāḥid b. Aḥmad b. `Alī b. `Āshir al-Anṣārī al-Fasī, al-Murshid al-mu`īn `alā ‘l-ḍarūrī min `ulūm al-dīn Footnote 115

-

○ Muḥammad al-Ṣāliḥ b. `Abd al-Raḥmān al-Awjalī, Dalīl al-qā’id li-kashf asrār ṣifāt al-wāḥid Footnote 116

-

○ Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan al-Shaybānī, `Aqīda al-Shaybānī Footnote 117

-

○ `Abd al-Raḥmān b. Aḥmad al-Waghlīsī, al-Muqaddima al-Waghlīsī Footnote 118

-

○ Muḥammad al-Ṭughūghī b. Muḥammad Inālbush al-Sūqī, Nazm `aqīda sūra al-ikhlāṣ and Shāfiyya al-qalūb Footnote 119

-

○ Abū `Imrān al-Jurādī, Kitāb fi tawḥīd Footnote 120

-

○ Abῡ `Abd Allāh Muḥammad b. `Umar, al-Bida` al-shayṭāniyya Footnote 121

-

○ Muḥammad b. `Uthmān b. Aḥmad al-Baghūnī al-Awsī (Aūsī), Bada’ al-āmālī Footnote 123

-

○ `Alī b. Muḥammad al-Sakhāwī, `Aqīda al-Sakhāwī and al-Kawkab al-waqād Footnote 123

Devotional and spiritual counsel, esoteric sciences, other

-

○ Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. Marzūq al-Tilimsānī, Qasīda al-munfarija Footnote 124

-

○ Abū Madyan Shu`ayb b. al-Ḥusayn al-Anṣārī al-Tilimsānī, Maqṣūra al-jawahir and Istighfār Abu Maydan Footnote 125

-

○ Wahhab b. al-Wardī, Kitāb fī al- mawā`iẓ Footnote 126

-

○ Muḥammad al-Wālī b. Sulaymān al-Fulānī al-Bāghirmāwī al-Barnāwī, Manhal mā’ al-`athb li-`ilm asrār ṣafāt al-rabb Footnote 127

-

○ Muḥammad b. Salāma b. Ja`far b. `Alī al-Quḍā`ī, al-Shahāb fī al-mawā`iẓ walādan Footnote 128

-

○ Bad b. al-Faqih Sanba b. Buḍ al-Fulānī, Manẓῡma fī al-mawā`iẓ and Qaṣīda Banat su’ād Footnote 129

-

○ Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Zarnūjī, Ta`līm al-muta`allim li-tarīq al-ta`llum Footnote 130

-

○ Ibrāhīm b. Mas`ūd b. Sa`īd al-Ilibīrī, Qasīda tā’iyya Footnote 131

-

○ `Alī al-Wa`īẓī, Manẓῡma fī al- mawā`iẓ Footnote 132

-

○ `Alī b. Abī Ṭālib al-Qurashī al-Hāshimī, `Aqīda al-imām `alā Ibn Abi Ṭālib and Manẓῡma fī al- mawā`iẓ and Makhtῡb fī al-naṣā’iḥ Footnote 133

-

○ Aḥmad al-Bakkā`ī b. Sīdī Muḥammad Sidi al-Mukhtar al-Kuntī, Qasīda fī tawassul and al- Qasīda al-ma`rῡfiyya Footnote 134

-

○ Sīdi Muḥammad b. Sīdi al-Mukhtār al-Kuntī, variousFootnote 135

-

○ Sīdi al-Mukhtār b. Aḥmad b. Abī Bakr al-Kuntī, variousFootnote 136

Sufism (taṣawwuf)

-

○ `Abd al-Qādir b. `Abd Allāh b. Mūsa al-Jaylānī, Qasīda al-Jaylānī and Qasīda al-ghuthiyya and Kitāb fatḥ al-ghaib Footnote 137

-

○ al-Ḥasan b. Mas`ūd al-Yūsī al-Marrākashī, Dāliyyat al-Yῡsī Footnote 138

-

○ Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. `Abd al-Karīm b. `Aṭṭā’ Allāh al-Iskandarī, Kitāb al-Ḥikam Footnote 139

-

○ Aḥmad b. Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. `Īsā b. Zarrūq al-Burnusī, Qawā’id al-Zarrῡq Footnote 140

-

○ Yūsuf b. Sa`īd al-Filālī, al-Durur al-munaẓẓama Footnote 141

-

○ Ḥasan b. Abī al-Qāsim b. Bādīs, al-Nafḥa al-qudusiyya Footnote 142

Appendix B: The 34 SAVAMA-DCI Libraries