In 2008 a sizable trench was excavated at the ancient Zoque city of Yoquí, also known as Chiapa de Corzo, in which two massive axe offerings were uncovered. This finding triggered a second season of excavations in 2010, and a large test unit placed atop Mound 11 revealed one of the most relevant finds for the archaeology of Chiapa de Corzo: the tomb of one of the earliest lords of the site (Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018; Figure 1). Other tombs of high-ranking individuals had been found previously at Chiapa de Corzo, like those documented from Mound 1 in the 1950s by the New World Archaeological Foundation (Agrinier Reference Agrinier1964, Reference Agrinier1975; Clark Reference Clark and Ségota2000; González Cruz and Cuevas Reference González Cruz and Cuevas1998; Valverde Reference Valverde and Ségota2000). What is notable about the recent tomb is its location in one of the pyramids that comprises the E-group at the site. Indirect dating from associated ceramics indicates that the tomb is some 2,700 years old (ca. 700 b.c.), making it the oldest tomb inside a pyramid uncovered to date in Mexico (Bachand and Lowe Reference Bachand and Lowe2012; Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018). In this article we focus on two objects found inside the tomb—two pyrite mirrors that were taken out of circulation from their social network and buried with their owners for use in the afterlife (it is unknown if the mirrors were used by the couple in life or if they were made exclusively for the burial). Why are these objects important? Firstly, the type of mirror recovered is unexpected, as the Olmec style one-piece concave mirror is what is typically seen in the Middle Preclassic. Although several hematite mirrors have been reported for coastal Chiapas (Cheetham Reference Cheetham2010), to our knowledge, not a single example of this type has been found in Preclassic sites of central Chiapas, albeit there has not been much research on the earliest and deepest occupations of these settlements. Secondly, the manufacturing techniques used to create the mirrors in general and the pyrite inlays in particular are unique. Why were these mirrors at the site of Chiapa de Corzo?

Figure 1. Area at the base of Mound 11 where, in 2008, an axe offering was located and an exploration trench conducted in 2010. Photo by Héctor Montaño, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia; Gallaga and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018:Figure 23.

The Zoque site of Chiapa de Corzo

The Zoque culture and its language in particular is derived from the Mixe-Zoquean linguistic family, whose speakers once occupied many areas of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Coast of Chiapas in the Early Preclassic and earlier (Campbell Reference Campbell1988; Campbell and Kaufman Reference Campbell and Kaufman1976). Their descendants can still be seen walking, eating, talking, and laughing, as part of the modern Chiapa de Corzo community made up of a rich cultural mix that includes Chiapanec and Hispanic roots. The archaeological site of Chiapa de Corzo constitutes one of the oldest human settlements in the region with continual occupation. Its earliest vestiges date back to the period 1500–1200 b.c., which coincides with the emergence of pre-Hispanic cities in the swampy regions of Tabasco and Veracruz, known as the nuclear area of Olmec culture, with communities such as San Lorenzo and La Venta (Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018).

Ancient Mixe-Zoquean groups settled in a region known as the Central Depression of the state of Chiapas, which is a long valley extending from the Sumidero Canyon on the outskirts of Tuxtla Gutiérrez northwest to the border of Guatemala, delimited by the Sierra Madre to the south and by the central highlands to the north (CONANP 2008; Helbig Reference Helbig1964; Figure 2). This natural corridor was of vital importance for the development of Zoque communities in general and for Chiapa de Corzo in particular, since it was a key route for people, materials, and ideas migrating from the Pacific coastal region to the swamps of Tabasco (Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018). The presence of significant quantities of non-local materials, such as jadeite jewelry, pyrite mosaics, and obsidian tools are evidence of this, as well as ceramic figurines and stone axes with Olmec motifs found at the site (Bachand and Lowe Reference Bachand and Lowe2011:83). A demonstration of the movement of ideas through this region is the so-called Middle Formative Chiapas pattern, which consists of an E-group assemblage and large platforms arranged along a north–south axis; this distinctive site layout pattern is seen at large Middle Preclassic centers in the Central Depression (Clark and Hansen Reference Clark, Hansen, Inomata and Houston2001; McDonald Reference McDonald1999), with a variation reported recently from the Usumacinta region in Tabasco (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, López, Fernández-Díaz, Omori, Méndez Bauer, Hernández, Beach, Cagnato, Aoyama and Nasu2020).

Figure 2. Map showing the location of Chiapa de Corzo and other sites of Chiapas at the Great Isthmus of Tehuantepec region. Drawing by Roberto Carlos Hoover; Gallaga and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018:Figure 1.

The archaeological zone of Chiapa de Corzo is known locally by the Chiapanec term Soctón Nandalumí, which means “water that runs under the hill.” The Zoque term for the site is Yoquí (the black place; Becerra Reference Becerra1932). Work by New World Archaeological Foundation (NWAF) archaeologists in the 1950s, and later salvage projects by the NWAF and Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) archaeologists have identified just over 200 structures at the site, arranged around courtyards or plazas, which formed a large settlement, taking advantage of the natural topography of the area (González Cruz and Cuevas Reference González Cruz and Cuevas1998; Figure 3). The plateau on which the site was built presents archaeological remains some 1,200 m from north to south and 1,800 m from east to west. The earliest remains at the site are primarily sherds of the Cotorra phase (1100–900 b.c.); no structures or other type of archaeological context had been identified for these early years of the Chiapa de Corzo community. Around 900 b.c., the first public, non-residential structures began to be erected, such as Mounds 7, 11, 12, and 13, which formed the initial nucleus of the site. Mounds 11 and 12 are particularly interesting. Mound 11 is somewhat squared and Mound 12 is rectangular, with a north–south axis. Mound 11 has a stairway on the east side and Mound 12 faces Mound 11. Together they form a complex of astronomical commemoration, called E-group by the researchers of the Preclassic or Formative period. It is identified as a great architectural solar observation system to measure the passage of the sun and stars, as well as to regulate agricultural and religious activities (Bachand and Lowe Reference Bachand and Lowe2011; Clark Reference Clark and Ségota2000; Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018; González Cruz and Cuevas Reference González Cruz and Cuevas1998; Valverde Reference Valverde and Ségota2000).

Figure 3. Chiapa de Corzo site map. Drawing by Roberto Carlos Hoover, New World Archaeological Foundation, after original plans by Eduardo Martínez and Arnoldo González Cruz; Gallaga and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018:Figure 3.

Around 700 b.c., Chiapa de Corzo underwent a social reorganization, reflected in the ceremonial architecture, which gave the settlement a more formal character. New temples and platforms were built, and old ones were modified or expanded according to an architectural plan oriented from north to south. This architectural pattern, as mentioned previously, is referred to as the Middle Formative Chiapas plan, which also turns out to be very similar, if not identical, to the site layout of La Venta, indicating a close relationship between these two pre-Hispanic communities in the Middle Preclassic. New research in the region has revealed a variant of this plan—what has been identified as the Preclassic Usumacinta pattern—which is distinguished by a rectangular platform upon which E-group structures were located, as seen at the site of Aguada Fénix, and at many others in Tabasco (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, López, Fernández-Díaz, Omori, Méndez Bauer, Hernández, Beach, Cagnato, Aoyama and Nasu2020). These new data illustrate how interconnected culturally, economically, and probably politically, these Preclassic communities were.

Between 600 and 500 b.c., the construction phase of what would be a second plaza began at Chiapa de Corzo, slightly to the southeast of the E-group, with the center of power moving to a second key location (Bachand and Lowe Reference Bachand and Lowe2011; Clark Reference Clark and Ségota2000; Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018; González Cruz and Cuevas Reference González Cruz and Cuevas1998; Valverde Reference Valverde and Ségota2000). Between 450 b.c. and a.d. 250, the region underwent another political, economic and cultural rearrangement. La Venta was looted and destroyed around 400 b.c., perhaps by rival groups from the Maya Lowlands, eager to assume economic control of the region, marking the end of what some researchers have called the Pax Olmeca of the Middle Preclassic (Clark and Pye Reference Clark, Pye, Love and Kaplan2011). Around 300 b.c., the inhabitants of Yoquí began to trade with the Lowland Maya, especially with the new center of power, the community of El Mirador in the Peten, and perhaps with other zones such as Campeche and Yucatan. Cultural exchanges with the states of Tabasco, Veracruz, and Oaxaca were also expanded (Bachand and Lowe Reference Bachand and Lowe2011; Clark Reference Clark and Ségota2000; Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018; González Cruz and Cuevas Reference González Cruz and Cuevas1998; Valverde Reference Valverde and Ségota2000). The period of Maya influence came to an end around a.d. 100, and coincided with the collapse of El Mirador in Guatemala. Between a.d. 200 and 550, Chiapa de Corzo began to interact with the western side of the state of Chiapas, especially with Juchitan and Tehuantepec. Some researchers maintain that Chiapa de Corzo was abandoned by the Zoque around a.d. 700, or at least had few inhabitants and demonstrated little activity. In any case, the site did not remain dormant for long, since a migrant group of Otomangue speakers from Central America, known as the Chiapanec or Chiapa, entered the region around a.d. 800–900 and came to dominate much of the Central Depression, displacing the Zoque population to settlements in the northwestern area of the state, where they are found today (Bachand and Lowe Reference Bachand and Lowe2011; Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018).

Mirrors

Human beings like to know who and what they are, to change the way they see themselves, and how the things they acquire or own say something about them and the community to which they belong. This ability to understand and transform our environment led to the creation of a universe of objects that help us to understand, interact and change our environment into a familiar landscape, to name it, and with that act to make it our own. Among this great universe of artifacts, mirrors or reflective surfaces have occupied an important place in the human mind. Pendergrast (Reference Pendergrast2003:13) states that “the ability to recognize oneself in the mirror seems peculiar to higher primates,” but particularly among humans. Few animals on this planet have this capacity for abstraction and recognition. There is not a single human group on the planet that has not looked for a way to recreate its image on some surface and not been captivated by its reproduction in a mirror or other reflective surface. Just to mention a few of the ancient cultures who created objects that satisfied the need to have and control reflective surfaces, there were the Hindus, Chinese, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Incas, Aztecs, and Mayas (Albenda Reference Albenda1985; Baboula Reference Baboula and Serghidou2000; Beazley Reference Beazley1949; Bulling Reference Bulling1960; Cameron Reference Cameron1979; Cammann Reference Cammann1949; Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Lilyquist Reference Lilyquist1979; Pendergrast Reference Pendergrast2003).

The objects and artifacts that we use, possess or want are a reflection of our position in the society in which we live or the level to which we aspire. In archaeological research, certain artifacts are identified or recognized as items that convey status or prestige to their holders; mirrors were one such category in ancient times, when many reflective artifacts were created. They were often used as beauty or aesthetic accessories, but not always. Today, mirrors are considered typical household items; in the past they were not. Crafting them was something special and rare; the vast majority would likely have been commissioned, and therefore they were highly valuable. In ancient times, people who could and did have mirrors were members of the upper class, such as kings, priests, merchants, high-ranking military personnel, dignitaries, ambassadors, or high administrators (Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016).

The production of mirrors and other reflective objects was complex and time-consuming, and required access to various materials, as sumptuous as gold and silver or as common as iron, hematite, obsidian, or pyrite, as in the case of mirrors made in the Americas, which stand out within the universe of pre-Hispanic artifacts for their aesthetics and craftsmanship (Blainey Reference Blainey2007; Gallaga Reference Gallaga2014, Reference Gallaga, Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Healy and Blainey Reference Healy and Blainey2011; Pereira Reference Pereira2008; Salinas Reference Salinas Flores1995). Undoubtedly, these artifacts were used for mundane purposes in domestic contexts—for example, to assess the viewer's facial features. However, this was not the only purpose for creating and owning a mirror. Given their ability to project a reverse reflection of the viewer's reality (where the right becomes the left and vice versa), mirrors were used as divinatory or supernatural portals to communicate between two parallel dimensions, worlds, or realities (Blainey Reference Blainey2007; Gallaga Reference Gallaga2014, Reference Gallaga, Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Healy and Blainey Reference Healy and Blainey2011).

Mirrors were also often seen as a means of contact with ancestors and, more importantly, with the gods. It is not difficult to imagine complex ceremonial activities, accompanied by singing and dancing in secluded places, perhaps involving fasting and the ingestion of hallucinogens. Such rituals might have been necessary to prepare and train the body and mind to be in contact with the spirits, whose advice, guidance, and support was important in decision-making or developing a course of action. The individual or the group of individuals who carried out these activities, conceived as required tasks for the common good of the whole community, would have acquired great prestige or position within their society, regardless of whether the individual was a ruler, advisor, priest, shaman, sorcerer, or healer.

Here, we address pyrite mirrors produced in the cultural region known as Mesoamerica, whose manufacture, precision assembly, and sacredness render them one of the most elaborate of pre-Hispanic objects. In particular, the focus is on two pyrite mirrors found at the site of Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas, Mexico, which we believe could represent good examples of early attempts to create what would become the hallmark Classic period pyrite mirrors.

Mesoamerican mirrors

The place of origin for these mirrors is still debated. For Mesoamerica, mirrors existed as early as the Early Preclassic period and appear to have peaked in use during Classic times, although they were around until the arrival of the Spaniards (Carlson Reference Carlson and Benson1981; Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Heizer and Gullberg Reference Heizer, Gullberg and Benson1981; Soustelle Reference Soustelle1984; Taube Reference Taube and Berlo1992; Zamora Reference Zamora2002). Their functions seem to have changed over time and ranged from being highly prestigious ceremonial items in the Early Preclassic period to being more common objects available in Aztec markets in the Late Postclassic era (Gallaga Reference Gallaga2014; Mohar Reference Mohar1997; Sahagún Reference Sahagún1985; Taube Reference Taube and Berlo1992; Zamora Reference Zamora2002). There has been renewed interest in these artifacts, building on what is already known in Mesoamerican prehistory (Ekholm Reference Ekholm1973; Gallaga Reference Gallaga2014, Reference Gallaga, Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Pereira Reference Pereira2008). For the objectives of this article, we will focus on the first two periods.

Early/Middle Preclassic period, 1400–400 b.c.

The first mirrors recorded in an archaeological context were located in the Olmec region, particularly at the site of La Venta (Carlson Reference Carlson and Benson1981; Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Gullberg Reference Gullberg, Drucker, Heizer and Squier1959; Heizer and Gullberg Reference Heizer, Gullberg and Benson1981; Pires-Ferreira and Evans Reference Pires-Ferreira, Evans and Browman1978). These mirrors are typically made of metallic minerals (magnetite, hematite, and ilmenite), formed from a single piece, with a finely polished concave surface and, in some cases, with perforations, quite possibly for use as pendants or pectorals. This type of concave mirror is thought to have been used for diffracting sunlight and for lighting a fire (Ekholm Reference Ekholm1973; Lunazzi Reference Lunazzi, Gallaga M. and Blainey2016). Unfortunately, there has been limited analysis of the manufacturing process of this Olmec mirror type, so it is not possible to compare it with pyrite mirror production techniques. It is possible that experimentation with materials led to the discovery of reflective characteristics, such as those seen in magnetite, hematite, and ilmenite. Most likely, craftsmen created a flat surface on a single stone, upon which they later made the concave area to the desired size, and then polished the piece. Suspension holes (Type # 3 being the most common), when they are present, would be undertaken last. Why pyrite was not a focus of interest for early craftsmen remains an unanswered question.

Several small Olmec-style iron-ore mirrors, both whole and partial, have been reported from Paso de la Amada (9 items) and Cantón Corralito (10 items) on the Pacific Coast of Chiapas during the Early Preclassic Cherla phase (1400–1300 b.c.; Cheetham Reference Cheetham2010). Cantón Corralito, in particular, had close ties with the early Olmec center of San Lorenzo. According to Cheetham (Reference Cheetham2010:434), the iron ore might have been imported in a raw state from Oaxaca or western Chiapas, but probably most or all of the mirrors came from the Gulf Coast region or elsewhere to Chiapas in a finished state. To date, none of these specimens have been analyzed for composition or manufacture. In the same Mazatán region, a large fragment of a large mirror was found at the Los Álvarez site (John Clark, personal communication 2021). A fragment of an unfinished iron-ore mirror was also located in excavations at Mirador-Plumajillo, at the western end of the Central Depression; it was found together with more than 2,000 pieces of ilmenite and magnetite (worked and unworked) in a probable workshop area for the production of multi-perforated blocks during the Early Olmec Pac phase (1300–1200 b.c.; Agrinier Reference Agrinier1984:81). Other examples of this type are reported from Cara Sucia in El Salvador, a looted site in the Pacific piedmont, close to the border with Guatemala (Bruhns and Amaroli Reference Bruhns and Amaroli2011).

Early/Late Classic a.d. 150/200–900

In this phase, the manufacture of mirrors undergoes a radical transformation: they begin to have flat surfaces instead of concave; they are not made from a single piece, but have a base on which multiple polygonal pyrite tesserae are placed in a mosaic fashion. This change represents a technological advance and innovation, as the manufacture of mirrors allowed greater aesthetic freedom to develop designs with the pyrite mosaics and, in some cases, adornments on the back of the base (Ekholm Reference Ekholm1973; Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Pereira Reference Pereira2008; Taube Reference Taube and Berlo1992).

Teotihuacan is considered one of the pyrite mirror workshop centers for this period, but there have not yet been adequate manufacture analyses to prove this. In addition to pyrite, the Teotihuacan people were interested in other reflective materials, such as mica used to make mirrors or adornments, or the possible decoration of a newly discovered tunnel under the Plaza de la Ciudadela with pyrite pieces (Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Gazzola et al. Reference Gazzola, Julie, Calligaro, Gallaga M. and Blainey2016). Nonetheless, we cannot rule out the existence of other important manufacturing centers, such as the valley of Oaxaca or the Maya Highlands, as could be the case for the mirrors in this analysis (Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Mohar Reference Mohar1997; Pires-Ferreira and Evans Reference Pires-Ferreira, Evans and Browman1978). Recent analyses have been undertaken on the pyrite mosaics from the Maya site of Tak'alik Ab'aj in the Pacific piedmont of Guatemala, dating to the end of the Late Preclassic, which are recorded as “reflectors” and not mirrors. These mosaics were made from several hundreds of small, quadrangular, pyrite tesserae, notably placed on a flexible base, possibly made of natural rubber. The purpose of these artifacts seemed to be “to reflect the sunlight with the movement of the holder” (Schieber de Lavarreda Reference Schieber de Lavarreda2024).

In general, pyrite-embedded mirrors consisted of four characteristic elements: base, adhesive layer, pyrite plates, and perforations. The description of each of these elements has been discussed elsewhere (Gallaga Reference Gallaga2014; Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Figure 4), so here, only a description of the pyrite mirrors of Chiapa de Corzo will be provided.

Figure 4. Components of a mirror and identified types of perforations. Drawings by Gallaga.

In the royal tomb at Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas, archaeologists found two square mirrors, each with a flat surface, composed of several thick pyrite pieces (or “tesserae”), surrounded by a thick layer of stucco on the edges, on what is believed to be an organic support, albeit decomposed (probably wood or natural rubber, like those discovered at Tak'alik Ab'aj), dating to 700–500 b.c. This find indicates that already somewhere in Mesoamerica, mirrors made with multiple pieces of pyrite were manufactured earlier than we thought. These Chiapa de Corzo pyrite pieces, however, are thick and rectangular in shape, very different from the thin, polygonal tesserae used in mirrors identified for the Classic period. In addition, it is the first find of this particular type of multiple pyrite mosaic mirror. The working hypothesis is that this is an early pyrite mirror at Chiapa de Corzo, which seems to fall somewhere between the styles of the Preclassic and Classic eras (Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018; Melgar Tísoc et al. Reference Melgar Tísoc, Ciriaco and Desruelles2018). In other words, someone, somewhere, began a new tradition of crafting mirrors out of several pyrite tesserae, instead of single pieces of magnetite, hematite, or ilmenite (Olmec style), and that is probably why the pyrite pieces are somewhat less elaborate in these mirrors from Chiapa de Corzo (Figure 5). In addition, since mirrors were a ceremonial item, the production changes in mirrors from the Preclassic to the Classic era are likely tied to changes in ritual behavior as well.

Figure 5. Pyrite tesserae from Mirror A. Photos by Melgar.

Archaeological context of Chiapa de Corzo Tomb 1 mirrors

Around 700 b.c., the ceremonial core of Chiapa de Corzo was centered on the E-group, formed by Structures 11 and 12, in whose plaza a pair of massive offerings and a cruciform deposit of stone axes of Olmec affiliation had been placed (Bachand and Lowe Reference Bachand and Lowe2011, Reference Bachand and Lowe2012). Structure 11 was the western pyramid of the E-group and may have reached 17 m in height in its last construction phase. The explorations carried out in the nucleus of this structure identified the presence of 20 overlapping constructions dating from the Middle Preclassic (ca. 900 b.c.) to Classic times. The earliest construction of the Chiapa III, Escalera phase (700–500 b.c.) was a clay-covered pyramid, 6 m tall, which guarded an important burial, Tomb 1. The placement of the funerary enclosure of one of the first Zoque dignitaries and his probable consort in Structure 11, including rich offerings with a great variety of imported materials, seems to confirm the existence of a hierarchically organized society at this early stage of the site's history, with ties to late Gulf Olmec and other regions and the establishment of early exchange and communication routes (Lowe Reference Lowe2020).

Tomb 1 was placed under the floor in the central part of the upper temple; this structure associated with the floor seems to have been built of perishable materials, since only the postholes and clay floor remained. The tomb consisted of two adjoining chambers, walled with rammed earth and uncut stones (Figure 6). The roof was constructed with wooden planks and beams placed transversally, which had collapsed in antiquity, the traces of which could be seen during the excavation process, thanks to the imprints and carbonized remains preserved in the mud core. The main chamber contained the skeletal remains of a middle-aged male, who was entirely covered with bright red cinnabar. He was placed on his back, with his head to the north, and had been interred with exquisite ornaments and rare funerary items, made of jade, shell, pearls, and pyrite, indicative of his high social position. Along the sides of the enclosure, 16 ceramic vessels were deposited, some of them decorated with resist geometric patterns, as well as andesite axes in the same style as those found in the massive offerings in the plaza. Two additional individuals, an adolescent male and an infant, were deposited without offerings near the head of the principal individual, perhaps as attendants or sacrificial victims.

Figure 6. Plan of Tomb 1, Mound 11, Chiapa de Corzo, indicating the location of (a) Mirror A and (b) Mirror B. Drawing by Lowe and Roberto Carlos Hoover, Chiapa de Corzo Archaeological Project, NWAF (Gallaga and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018:Figure 40).

The tomb had a smaller annex to the north, where we found the remains of another regal individual, in this case a middle-aged female, who was placed in an extended position, with her head oriented to the east and her body covered with red cinnabar. The elaborate funerary ornamentation of this woman was similar to that of the male placed in the primary chamber, suggesting that the two interments were simultaneous; both presented the same kind of miniature beadwork, face/mouth coverings, belt pendants, quadrangular mirrors and ceramic vessels, all deposited as part of a single construction event in the mound.

The quantity and quality of preserved artifacts comprising the attire of the principals buried in the tomb is impressive for Middle Preclassic times. The offerings of Tomb 1—which included numerous jade ornaments, pearls, shells, pyrite mirrors, amber, quartz, and turquoise beads, as well as ceramics, hematite, and obsidian pieces—totaled 3,728 elements and provide information of great relevance for understanding cultural relationships and possible exchange routes. The mineralogical analyses of these objects, using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy, were carried out by members of the Institute of Physics (Instituto de Física) at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM; Manrique et al. Reference Manrique, Claes, Casanova-González, Ruvalcaba, García and Lowe2014). Clearly, the most abundant non-local trade item was jadeite, perhaps the most prestigious mineral resource for the ancient peoples of Middle America. According to the analysis performed by Manrique and colleagues (Reference Manrique, Claes, Casanova-González, Ruvalcaba, García and Lowe2014), jade artifacts from this context showed variations in their physical attributes, like color and transparency, but still revealed a degree of chemical compositional unity suggesting that they had all originated from closely related sources in the Motagua River Valley in Guatemala.

Especially striking was the deceased male's jade necklace—a remarkable composition of nearly 1,000 tiny beads, each measuring around 5 mm in diameter and spaced among 17 miniature jade “spoon” or “clamshell” pendants in Olmec style. The clamshells were crafted from superficially distinctive types of jade, including a translucent pale green that contrasts with the bright green of the round beads. Also, he was adorned with beaded strands of jade on his upper arms, wrists, knees, and ankles. At the back of his waist were three large beads that likely formed part of a belt; the central section of which was carved in the shape of a bird or a serpent head.

The woman's necklace was shorter and comprised of several tiny pearls, arranged with 24 jade pendants of varying quality, each delicately worked into the shape of aquatic birds, such as ducks and cormorants, which likely dangled from two perforated rods and were balanced with a large bead on the back of the neck. Her limbs were draped with hundreds of jade, iron-ore, and pearl beads. Each of her bracelets consisted of nearly 200 apple-green jadeite beads. Her calf and ankle ornaments resembled those of the male, save the addition of numerous iron-ore beads. As mentioned, the mineralogical analyses of these objects using XRF and IR and Raman spectroscopy were carried out thanks to the collaboration of specialists at the Institute of Physics at UNAM (see Manrique et al. Reference Manrique, Claes, Casanova-González, Ruvalcaba, García and Lowe2014). Unique to the female was an elegant belt adorned with small jade and amber beads, which was secured at her lower back by two large gourd-shaped beads arranged on either side of a jade tube, which had been carved to resemble a howler monkey's head.

Spondylus shells covered the mouths of both of the principals; however, the female's shell was more elaborate, having been carved into the shape of a tiny mask with eyepieces of polished shell. Polished obsidian disks lying nearby could have represented the eyes of the funerary masks. Unique to the male individual was a loincloth decorated with 126 mother-of-pearl shell beads. Another gender distinction was the presence of a stingray spine, probably a bloodletter, located on the right side of the woman's chest.

Of remarkable importance in this context was a quadrangular, stucco-surrounded mirror composed of pyrite plaques placed against the male occupant's right shoulder (Mirror A). A second mirror, larger than the one placed with the male, but poorly preserved, was placed next to the female's right knee (Mirror B). Other iron-ore artifacts were also associated with the tomb. A thin mosaic of polished hematite with a single perforation, maybe part of a larger element of attire, was noted on the center of his pelvis, surrounded by a circular zone of gray clay. The couple had distinctive dental incrustations: iron pyrite was inlaid into the male's upper incisors; and the woman had double incrustations in each of the upper lateral incisors. Finally, we uncovered evidence of a stucco mask deposited inside a bowl; the stucco was completely powdered, but there was a pair of mosaic eyes made of shell and hematite, still in their correct anatomical position (Bachand and Lowe Reference Bachand and Lowe2012).

Description of Tomb 1 mirrors

Mirror A, associated with the male occupant in Tomb 1, was the best preserved; it had a rectangular shape, measuring 10 ×15 cm approximately, and was composed of thick pyrite tesserae, several of them fragmented (Figure 7). The tesserae had a brilliant, dark gold color and averaged 2.5 cm wide by 4–5 cm long and 1–2 cm thick. Along the edges of the mirror there were still traces of a thin white stucco layer, about 2 cm wide, although the original support of the piece, probably made of wood, had not survived. The identification of the pyrite pieces was confirmed by portable XRF equipment of the Institute of Physics (UNAM), together with a slight presence of cinnabar from the red pigment that had covered the contents of the tomb (J. L. Ruvalcaba, personal communication 2013). Four pieces of this mirror were compared with modern pyrite minerals using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy at the Scanning Electron Microscope Laboratory of INAH, confirming the results obtained previously with XRF.

Figure 7. Mirror A, placed against the principal occupant's right shoulder in Tomb 1, Mound 11, Chiapa de Corzo. Photograph by Lowe, Chiapa de Corzo Archaeological Project, NWAF.

Mirror B, associated with the female occupant in the attached chamber, was found in very poor condition. It has a quadrangular shape, measuring 15 ×15 cm, with an irregular surface of a brownish-yellow color, a product of the corrosion on the artifact, and a thin white stucco border 1 cm thick (Figure 8). There was no evidence of the original support, which was possibly made of wood or another perishable material. The consolidation and restoration of the artifact, carried out by the Coordinación Nacional de Conservación (at INAH), contributed interesting data on its composition. The radiographic study showed that it was a mosaic composed of six thick tesserae, all of a quadrangular shape; these were surrounded by lime mortar and covered by a thin layer of corrosion. Again, using portable XRF equipment, it was possible to verify the presence of iron and sulfur in the mosaic pyrite pieces (FeS2; Portocarrero Navarro Reference Portocarrero Navarro2014:6).

Figure 8. (a) Mirror B, placed next to the female occupant's right knee, Tomb 1, Mound 11, Chiapa de Corzo. Photograph by Bruce Bachand, Chiapa de Corzo Archaeological Project, NWAF. (b) X-ray image of Mirror B in which some of the remaining pyrite tesserae can be seen. After Portocarrero Navarro Reference Portocarrero Navarro2014:Figure 1.

The use of this kind of pyrite mirror, as well as other distinctive mortuary practices identified in the Tomb 1 context—in particular, the Spondylus shell covering the deceased's mouth, probably as part of masks, the presence of highly elaborate jade, shell, and amber jewelry, and black-slipped ceramics—all point to the presence of an enduring local Zoque cultural tradition coexisting with Gulf Coast symbolic ties distinctive of Middle Preclassic times in southern Mesoamerica.

Another finding that confirms the presence of pyrite artifacts during the Middle Preclassic at Chiapa de Corzo was a rectangular pendant carved in low relief, depicting a reclining deer that was part of the funerary offering of Burial 4, found in the same structure (Bachand and Lowe Reference Bachand and Lowe2011:Figure 10). Other evidence of mirrors at the site includes a quadrangular piece with a ceramic worked-sherd backing covered with pyrite mosaics, reported as part of Offering 7-2 at Mound 7, in a late Middle Preclassic context; the pyrite pieces appear to have been held in place by lime mortar, although the pieces were very weathered, oxidized, and almost disintegrated (Lowe Reference Lowe1962:145, Plate 26-d4). It is likely that mirrors were in use at Chiapa de Corzo during the Early Classic period, as indicated by the presence of small, angular pieces of brilliant pyrite, probably from a mirror, found in looted Tomb 2 of Mound 12 (Mason Reference Mason1960:24). Other isolated pyrite mosaics were reported from this mound in Tomb 3 and Cache 12-11 (Mason Reference Mason1960:28, 29). According to Navarrete (Reference Navarrete1966:94), small pieces of pyrite could have been obtained from boulders in the Río Chiquito, which surrounds Chiapa de Corzo, where they are found as small spheres deep inside the cracks of boulders, but it is also possible that raw materials or manufactured mirrors were imported from other regions.

Technological analysis of the manufacturing traces of the lapidary objects

Due to the lack of production contexts for lapidary objects in Mesoamerica, like pyrite mirrors, Melgar (Melgar Tísoc Reference Melgar Tísoc2018; Melgar Tísoc and Solís Ciriaco Reference Melgar Tísoc and Ciriaco2009; Melgar Tísoc et al. Reference Melgar Tísoc2018) developed an experimental archaeology workshop, in operation since 2004, to perform traceological analysis of the manufacturing traces on lapidary items in Mesoamerican assemblages. Traceology is the study of any evidence of use-wear, manufacturing processes, residues, or surface alterations (Alonso et al. Reference Alonso, Baena and Canales2017; Gurova and Bonsall Reference Gurova, Bonsall, Bar-Yosef, Bonsall and Choyke2017).

The analysis of microwear marks produced through experimental archaeology can demonstrate that the manufacture or use of similar objects, following similar patterns, will leave characteristic traces that can be differentiated from each other (Ascher Reference Ascher1961; Binford Reference Binford1977; Velázquez Castro and Melgar Tísoc Reference Velázquez Castro and Tísoc2014). With this in mind, an object's modifications can be reproduced (abrasions, cuts, incisions, perforations, polished and brightened surfaces), based on the manufactured raw material and employing the tools and processes that are believed to have been used by the various peoples of Mesoamerica. Such indigenous knowledge and technology come from a variety of historical sources (Durán Reference Durán2005; Sahagún Reference Sahagún1985), archaeological data (Englehardt et al. Reference Englehardt, Caballero, Tísoc, Maldonado, Torres, Bernard and Carrasco2020; Melgar Tísoc Reference Melgar Tísoc, Alonso, Baena and Canales2017; Melgar Tísoc and Mathien Reference Melgar Tísoc, Mathien, Fábregas, Nelson and Rodríguez-Rellán2020; Velázquez Castro and Melgar Tísoc Reference Velázquez Castro and Tísoc2014), and proposals by researchers (Gallaga Reference Gallaga, Gallaga M. and Blainey2016; Mirambell Reference Mirambell1968; Smith and Kidder Reference Smith and Kidder1951).

The materials used in the experimental archaeology workshop include a great variety of rocks (volcanic, sedimentary, and metamorphic) and abrasives (sand, volcanic ash, obsidian powder, chert powder, hematite powder, quartz powder), as well as bone utensils (turkey and deer), spines (cactus), fiber (ixtle and sisal), reeds (Otatea acuminata), and skins (deer and rabbit; Table 1). A record of each experiment registered the following information: experiment identification number (consecutive); name of the experiment; the objective; materials used (specifying their characteristics and measurements); description of the procedures used (type and direction of movements); start and end time of the work.

Table 1. Materials employed at the experimental archaeology workshop.

During each experiment, detailed photographic records were taken, from the raw materials involved to the resulting reproduced modification. The modifications seen in the archaeological mirrors from Chiapa de Corzo were reproduced (abrasions and cuts; Figure 9).

Figure 9. Experimental archaeology on pyrite: (a) abrading with sandstone; (b) cutting with obsidian. Photos by Melgar.

For the traceological research, we analyzed seven inlays from Mirror A—two complete and five fragments with good surface and edge conditions. Unfortunately, the inlays of Mirror B are too corroded and weathered for analysis. Despite that, both mirrors show thick inlays with similar polygonal shapes (mostly rectangular and quadrangular), and the same lengths on two sides (15 cm).

Abrasions

The pyrite inlays from Mirror A have flat and regular surfaces, as a result of abrading with lithic tools (flat stones and/or metates). The experiments performed to reproduce this modification consisted of flattening the surfaces of the inlays, abrading them on different rocks, using a back-and-forth motion, without abrasives, or by adding moistened sand during work (Table 2).

Table 2. Experiments for abrading.

Cuts

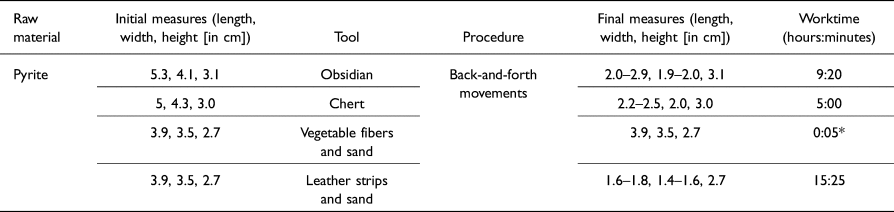

The inlays presented straight edges, as a result of cutting with stone tools or using an abrasive, together with leather strips or vegetable fibers stretched on a bow. The experiments performed to reproduce this modification consisted of cutting inlays with lithic tools (flakes and blades), as well as using abrasives, together with leather or fibers. In all instances, the tools were used in a back-and-forth motion (Table 3).

Table 3. Experiments for cutting.

*This experiment could not be completed due to the vegetable fibers (agave, ixtle, or sisal) quickly and continuously breaking (in seconds).

Along with the experiments, systematic comparisons were made between the modern and archaeological examples, with the help of a 10× magnifying glass and a stereoscopic microscope enhanced with an Olympia digital camera Tz s2-STS taking pictures at 10×, 30×, and 63×.

Finally, the characterization of the traces of manufacturing was undertaken with scanning electron microscope Jeol JSM-5900LV at 100×, 300×, 600×, and 1000× (Figure 10), in high-vacuum mode and using the same parameters (SEI signal, voltage of 20kV, distance of 10 mm, and 47 spotsize). The described variables and attributes included the following: the superficial characteristics, such as roughness, smoothing, porosity, and presence of particles, as well as the lines, bands, or textures presented in the micrographs. The approximate measurements of the lines and bands could be taken, thanks to the scale in microns incorporated into each image.

Figure 10. Analysis of the pyrite inlays from Chiapa de Corzo with SEM. Photo by Melgar.

Traceological analysis of the pyrite mirrors from Chiapa de Corzo

In general terms, all the analyzed pyrite pieces from Mirror A at Chiapa de Corzo showed polished flat surfaces crossed by some straight lines (Figures 11a and 11b). These traces, especially the fine lines, are closest in appearance to those experimental examples obtained by abrading directly on flat stones (Figure 11c), and differ from the smooth and rounded surfaces produced by the experimental abrading with abrasives (Figure 11d). It is important to note that for all the archaeological pieces, the observed lines were more diffuse on the front surfaces than on the back, probably because one side was polished and/or brightened, while the second was in contact with the base and the adhesive.

Figure 11. (a and b) Analysis of archaeological surfaces of artifacts from Chiapa de Corzo; and the comparison with experimental abrading (c) directly on flat stones and (d) with abrasives. Photos by Melgar.

Using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the diffuse straight bands measure 33 μm (Figure 12a). These marks are similar to the experimental traces produced by abrading with rhyolite metates and subsequently polishing with leather (Figure 12b), and differ from the traces produced by abrading with other stones, like basalt (Figure 12c) or sandstones (Figure 12d).

Figure 12. Analysis of surfaces with SEM: (a) archaeological inlay, compared with experimental abrading with (b) rhyolite, (c) basalt, and (d) sandstone. Photos by Melgar.

The pyrite inlays presented rugged edges and some diffuse, irregular lines (Figures 13a and 13b). These traces are closer to the experimental examples produced with obsidian flakes (Figure 13c) than to the straight lines obtained with chert flakes. With SEM, the edges showed fine lines of 0.6–1.3 μm in width (Figure 14a). These marks are similar to traces obtained by experimental cutting with obsidian flakes or blades (Figure 14b) and differ from the traces produced with chert flakes (Figure 14c). Also, the bands produced by other tools for cutting, abrading, or regularizing the edges are absent, confirming the employment of obsidian (Figure 15a).

Figure 13. (a–b) Analysis of edges of archaeological artifacts from Chiapa de Corzo; and the comparison with experimental cutting with (c) obsidian flakes and (d) chert flakes. Photos by Melgar.

Figure 14. Analysis of edges: (a) archaeological inlay, compared with experimental cutting with (b) obsidian flakes and (c) chert flakes. Photos by Melgar.

Figure 15. (a) Edge of pyrite inlay without bands from abrading tools; (b) experimental abrading with dacite. Photos by Melgar.

Discussion

The strategic position of Chiapa de Corzo in the Central Depression of Chiapas, along a route linking the coastal plains of the Gulf of Mexico with the Guatemala Highlands, in addition to the nearby confluence of the Grijalva and Santo Domingo rivers, favored the circulation of local and foreign materials and products and interaction with other regions (Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018:26; Sullivan Reference Sullivan2009:15). Evidence of this is the large amount of exotic stone artifacts recovered in archaeological contexts at the site, such as jade jewelry, pyrite mosaics, and obsidian tools (Bachand and Lowe Reference Bachand and Lowe2011:83). While there are non-local geological materials found at the site, this does not imply that the artifacts were imported as finished objects. Archaeologists uncovered objects (Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018:27, 70), such as the incised axe decorated with an Olmec image in Massive Offering 1 (Bachand Reference Bachand2013:34–35), whose method of production allows for the possibility of having been made locally at Chiapa de Corzo (Solís Ciriaco et al. Reference Solís Ciriaco, Tísoc, Lowe, Arroyo, Méndez and Ajú2016). In contrast, some of the worked jade might be considered Olmec goods, such as the belt beads in the shape of a monkey and pumpkins, or the miniature “spoon” and bead strands, which are very similar to items reported in offerings at La Venta (Bachand Reference Bachand2013:29). This dichotomy between local and foreign production is what we address for the pyrite mirrors recovered in Tomb 1 of Mound 11, since the nearest known deposits of this iron-ore material are located in the Maya Highlands of Guatemala, some 200–350 km away (Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018:102). Unfortunately, there are no documented workshops or reported evidence of mosaic mirror production for the era when these objects were deposited in the tomb at Chiapa de Corzo (Gallaga Reference Gallaga, Gallaga M. and Blainey2016:32).

From a technological viewpoint, we highlight the characterization of the manufacturing marks on the pyrite inlays as being produced by instruments of volcanic origin: rhyolite for abrading and obsidian for cutting. This is noteworthy because the majority of the lapidary objects recovered in Middle Preclassic contexts, such as the serpentine and jade axes analyzed with XRF and IR and Raman spectroscopy (Manrique et al. Reference Manrique, Claes, Casanova-González, Ruvalcaba, García and Lowe2014), as well as beads from Tomb 1 and the ear spools from Massive Offering 1, exhibited surfaces abraded with sandstone (Solís Ciriaco et al. Reference Solís Ciriaco, Tísoc, Lowe, Arroyo, Méndez and Ajú2016). Sandstone is locally available, and several flat slabs of this material have been recovered at the site, with channel marks that have been interpreted as the result of surface abrasion from polishing and sharpening axes (Bachand Reference Bachand2013:37).

In the case of the pyrite inlay edges, although they all have cuts made by obsidian tools (a volcanic rock), the surfaces of both mirrors were abraded by sandstone (a sedimentary rock). This technological particularity and the near absence of rhyolite tools in the site's lithic assemblage, except for one chopper (Lee Reference Lee1969:154), suggests that both pyrite mosaics were made elsewhere by a different group of lapidary artisans. Geological data from the region supports this idea, because while limestone, sandstone, and mudstone predominate in the surroundings of Chiapa de Corzo (Bachand Reference Bachand2013:37; INEGI 2008), the nearest sources of rhyolites are located 170 km away to the southeast, in the Motozintla Basin near the border with Guatemala (Caballero Miranda Reference Caballero Miranda2002; Sánchez Núñez et al. Reference Sánchez Núñez, Macías, Zamorano Orozco, Saucedo, Torres and Novelo2012:174). Interestingly, there are pyrite deposits close to this area in the adjacent Guatemala Highlands at Huehuetenango, Aguacatlan, and Quetzaltenango (Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018:102), only 80–100 km away from Motozintla. With this in mind, the technological and geological data reinforce the idea of non-local manufacture of the mosaic mirrors found at Chiapa de Corzo.

Thus, the near absence of rhyolite tools in the archaeological contexts from Chiapa de Corzo, as well as the potential Guatemalan origin of the pyrite, and the uniqueness of both mirrors in the lapidary assemblage of the site, all seem to indicate that the two pyrite mosaic mirrors found in Tomb 1 at Mound 11 were probably acquired through interactions with other groups from southeastern Chiapas or the Guatemala Highlands. The workshop from which the mirrors originated was unlikely to have been Tak'alik Ab'aj, a coeval site to Chiapa de Corzo on the Guatemala piedmont. Pyrite mosaic mirrors there are of a different type; they are made with dacite tools (Melgar Tísoc and Solís Ciriaco Reference Melgar Tísoc and Ciriaco2019)—dacite being a volcanic rock common to that area, and most of the grinding instruments and sculptures are made from it. Dacite produces texturized surfaces with bands of 40–50 μm (Figure 15b); such traces are absent in the Chiapa de Corzo artifact assemblage.

Another noteworthy aspect of the technology employed on the mirrors from Chiapa de Corzo is that it does not appear to have been the most efficient, since the absence of the use of abrasives would have increased the working time to produce them. Given this, the increased investment of working time must have increased the value of the items as prestige goods, which tend to be from scarce, non-local materials, created with specialized skills and secret or ritually sacralized techniques (Drennan Reference Drennan and Rattray1998:26–28; Inomata Reference Inomata2001:321). Perhaps cultural and symbolic aspects involved in the crafting of these objects favored pyrite mosaic mirrors, which allowed for new shapes and dimensions in these objects, in contrast to mirrors made from a single piece of specular hematite, ilmenite, or magnetite, like those reported in sites of the Gulf Coast, the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, the Basin of Mexico (Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016:16; Gallaga M. and Lowe Reference Gallaga M. and Lowe2018:82), the Pacific Coast of Chiapas (Cheetham Reference Cheetham2010), and El Salvador (Bruhns and Amaroli Reference Bruhns and Amaroli2011).

An additional difference between these single-piece mirrors and the lapidary objects from Olmec sites is the technology reported at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan, La Venta, and Arroyo Pesquero; manufacturing traces reported on the surfaces of a variety of objects from those sites indicated abrading tools made of sandstone and basalt (Bernard Medina Reference Bernard Medina2018, Reference Bernard Medina2020). While sandstone abraders were reported for Chiapa de Corzo, basalt is absent, and none of the pyrite inlays from Mirror A presented traces of both sandstone and basal tools. Based on this, we can discard a Gulf Coast Olmec origin for the Chiapa de Corzo mirrors and address new questions about their cultural provenance and place of manufacture.

Conclusions

We have provided the traceological analysis of Chiapa de Corzo Mirror A using experimental archaeology and SEM to examine the manufacture of this object. Based on these analyses, we identified the materials and techniques employed to craft them. Surprisingly, the abrading tool used on the mirrors is from a non-local volcanic rock, absent in the archaeological record of Chiapa de Corzo, and contrasts with other lapidary items at the site produced with sandstone slabs and boulders of the region. The various technological patterns demonstrated on the mirror could be the result of the development of workshops with specialized artisans, potentially located at several sites. Following this idea, the pyrite inlays might have been crafted outside Chiapa de Corzo, given the near absence of rhyolite tools at the site, while the rest of the lapidary objects were crafted from tools recovered in the archaeological record, like sandstone abraders. Given that the particular tools employed were scarce or specialized, along with the possibility that workshops from different sites were involved, this would also signal increased labor investment in the lapidary objects, resulting in increased prestige.

In addition, technological analysis of the tools used to create the traces of manufacture indicates that pre-Hispanic artisans who created the pyrite mirrors did not use the most efficient tools or techniques to make them, like the employment of abrasives in the abrading procedure to reduce the worktime for this modification. Perhaps they were more interested in increasing the value of the items based on the increased labor invested in its production, and not in the efficiency of their production. It is also important to keep in mind that pyrite mirrors were not common household objects; they were expensive prestigious elite items, as well as ceremonial/ritual objects (Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016).

The pyrite mirrors found at the site of Chiapa de Corzo seem not to have been crafted there; potentially, they were commissioned by the ruling couple buried inside Mound 11, or they might have been received as precious gifts from other dignitaries as part of regional political alliances, prestige objects then taken out of circulation after the couple died. It is interesting that there are several objects of possible Olmec origin at Chiapa de Corzo, but so far not a single Olmec mirror type has been recorded at the site or in the region. Olmec type mirrors reported from the Chiapas Pacific Coast and the western Central Depression are dated to Early Preclassic times, contemporaneous with San Lorenzo in the Gulf Coast. At some point these Olmec mirrors with concave surfaces were no longer produced. The so-called “reflector” mirrors at the site of Tak'alik Ab'aj, composed of multiple pyrite tesserae, may have been the new regional fashion for the Late Preclassic/Early Classic period (Schieber de Lavarreda Reference Schieber de Lavarreda2024).

In addition to the change in mirror styles and manufacturing techniques, it is also worthwhile considering the significant shift in the selection of raw materials—from the black/gray ilmenite, hematite, and magnetite preferred in early times, material probably obtained in Oaxaca or western Chiapas, to the golden pyrite mosaics characteristic of the Maya Highlands. This change might have involved a modification in symbolic values and ceremonial/ritual requirements, as well as shifting exchange routes or political alliances. At this point, it is not yet clear why there was a change from a single concave piece to multi-piece mirrors, but to date, the Chiapa de Corzo mirrors represent two of the earliest versions of the pyrite mosaic mirror type that would become a hallmark in the Classic period in Mesoamerica. We hope these data will be enriched by new findings, studies, and comparisons with coeval pieces, both in the Zoque region and the Mayan Highlands, as our knowledge of the Middle Preclassic period and its complex cultural interactions advances.