Far from confirming the inevitability of the yuan’s rise, China’s uncertain effort to internationalize its currency has exposed the profound struggles that lie behind the country’s larger push to transform its economic model. – Sebastian Mallaby and Olin WethingtonFootnote 1

International currency use is obviously path dependent. It is not a level playing field; market actors and governments are already locked into certain patterns of behavior, institutionally and linguistically. Newcomers, therefore, start at a distinct competitive disadvantage that may be difficult to overcome. – Benjamin CohenFootnote 2

Introduction

Following the turbulence of the 2008 global financial crisis, the Chinese economic strategy to expand the global usage of the renminbi (RMB) – the currency of the People’s Republic of China (PRC, hereafter also China) – has attracted growing research interest.Footnote 3 Rolled out by the ruling Communist Party of China (CPC), this strategy appears globally significant because of the opportunities it presents for generating economic growth both offshore (primarily in foreign financial centres) and onshore (in targeted locations within China). At the same time, there is uncertainty over its rationale and impact. One segment of academia and policymaking circles considers RMB internationalization from a historically successive vantage point, with one reserve currency potentially succeeding another, and asks whether this process signals a movement towards a core condition of reserve currency status: full capital account convertibility.Footnote 4 This teleological perspective derives from the post-Second World War evolution of the US dollar from a domestic to a fully convertible and freely traded global reserve currency, and assumes any subsequent internationalization process should arrive at the same outcome.Footnote 5

Emerging empirical evidence indicates, however, that RMB internationalization is not evolving towards the same endpoint. Geographically, its global reach is connected in large part to the Chinese state. Functionally differentiated connections have been established between global financial centres designated by Beijing – first Hong Kong, followed by a fast-expanding list including London, Luxembourg, Singapore, and more – and selected territories within mainland China.Footnote 6 RMB-denominated loans were also granted to drive infrastructural construction in countries participating in the signature foreign policy of the contemporary Xi Jinping administration: the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI).Footnote 7 Historically, both the method and motivation underpinning this new strategy reflect a longstanding but highly adaptive quest for absolute political control over the domestic financial system since Mao Zedong proclaimed the formation of a new Chinese party-state in 1949. Even within the context of deepening global economic integration, set in motion by Deng Xiaoping with a series of ‘reform and liberalization’ policies after assuming the CPC leadership in 1978, the evolution of the Chinese financial system has been a spatially selective and path-dependent process to reproduce state-directed development.Footnote 8

Between 1949 and the early 1980s, credit provision was a function of the fiscal system, which in turn fortified state control over prices and resource distribution. While the banking system was de-coupled from the fiscal system after 1978, the CPC continued to control financial capital through a twofold policy of direct participation (the ‘Big Four’ banks, namely Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China, China Construction Bank, and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, are state-owned) and administrative regulation (multiple policies have been implemented to facilitate financial repression at the national, provincial and municipal level). This persistent control was explicitly emphasized during the summer of 2015 when the Chinese government pledged to intervene in domestic financial markets whenever it deems ‘necessary’.Footnote 9 At the same time, as this article will show, the Chinese government moved from a stance of ‘gradually’ attaining full capital account convertibility – which recognizes full convertibility as a necessary endpoint for global economic integration – to re-defining convertibility according to its own terms and needs.

Taken together, these developments raise two interrelated questions. First, what is the historical rationale of RMB internationalization, and what are its implications? Second, how does the rationale for, and implications of, RMB internationalization distinguish this process from the emergence of the US dollar as the global reserve currency? Addressing these questions first entails evaluating the commensurability between teleological conceptions of the RMB’s emergent global role and the evolution of the RMB as a national currency. Here, the historical analytical approach of Patrick Neveling is instructive: what appear as moments of radical ruptures may occlude transformative processes occurring before these moments, consolidate outcomes of earlier ruptures, and/or mark the continuities of established periods and/or practices.Footnote 10 Moments of ruptures at one level (e.g. the national) may not, however, engender the same impact at another (e.g. the global). A critical evaluation of RMB internationalization as a potential moment of radical rupture – i.e. fundamentally succeeding the dollar as the global reserve currency – therefore requires foregrounding the connections between ruptures, consolidations, and continuities at both the national and global levels.

Working towards this aim, this article will first frame the RMB internationalization process as a historical palimpsest that comprises three critical moments following the establishment of the PRC. These moments are, namely, the RMB as a ‘unifying’ tool in the Chinese state formation process (moment one), the consolidation of RMB value after 1994 (moment two), and RMB internationalization as a response to the 2008 global financial crisis (moment three). This historical framing underscores how changes evolved in tandem with an ongoing commitment to sustain absolute macroeconomic control – a commitment first instituted during the Mao-era (1949-76). The global historical significance of these three moments will then be ascertained through a comparison with the rationale and effects of dollar internationalization. This two-step approach collectively demonstrates how RMB internationalization does not constitute a rupture in global historical terms; rather, it paradoxically consolidates a dollar-centric global monetary system because of the CPC’s path-dependent national macroeconomic management.

This article will be laid out in six parts. The second section critically evaluates how currency internationalization has been historicized by first presenting the limits to teleological accounts before highlighting the problems associated with equating other currencies’ historical trajectories to RMB internationalization. If the history of the US dollar provides a guide, full convertibility was and remains an important precondition for the formation of a global reserve currency. That full convertibility is not occurring in tandem with RMB internationalization calls for a more open-ended historical inquiry. Sections three to five present and analyze the significance of each critical moment. Situating existing concepts within the context of path-dependent and spatially-selective macroeconomic regulation in post-Mao China, they explore specifically how the fixed exchange rate regime and credit provision enable the CPC to retain Mao-styled ‘fiscalization’ of the financial system and simultaneously deepen global economic integration. The global historical significance of these three moments will be assessed in relation to the dollar’s internationalization rationale and trajectory in section six. The conclusion will summarize the article’s key contributions.

The rationale of RMB internationalization: an analytical approach

The ‘internationalization’ of nationally issued currencies has corresponded with the emergence of large and globally influential economies. This first began with the far-reaching influence of the British Empire from the nineteenth century to the end of the Second World War; the adoption of the US dollar as the ‘anchor currency’ for gold convertibility following the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement; the offshore expansions of the Deutsche Mark and the Japanese yen as Germany and Japan became net exporters in the 1970s; and, more recently, the adoption of a common currency, the Euro, across the European Union (EU) common market. As Peter Kenen puts it, an ‘international currency is one that is used and held beyond the borders of the issuing country, not merely for transactions with that country’s residents, but also, and importantly, for transactions between non-residents’.Footnote 11 Underpinning this process are various combinations of the following preconditions: unrestricted trade in the currency domestically and abroad; the ability of all firms to invoice in that currency regardless of whether trade is actually conducted with the issuing country; the ability of foreign financial institutions to hold the currency in volumes they deem sufficient; the ability of these institutions to issue equity and debt instruments in this country; and the ability of financial institutions of the issuing country to issue these instruments in foreign markets.Footnote 12 In short, effective internationalization entails convertible capital accounts.

Capital account convertibility is widely construed as the fundamental basis of a global ‘reserve’ currency. Standard economic definitions portray capital account convertibility as the freedom to convert local financial assets into foreign financial assets and vice versa. Conversion prices are to be determined by the market, with minimal state intermediation or regulation. While this characteristic has taken on a veneer of universality because of the joint advocacy of international free trade by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Trade Organisation (WTO), it is in fact an historically specific aspect of the global political economy. Indeed, convertibility incorporates three components of international trade and capital flows that have only become prominent after the Second World War, and many of these evolved at first in parallel with developments in Mao-era China before converging in varying degrees after the Chinese political economy’s (re)turn to market-like rule in 1978.

The first component is ‘Foreign Direct Investment’ (FDI). This encompasses investments in a local incorporated entity or a joint venture with a local entity, and which are deemed unlikely to pull out at short notice. FDIs have tended to be concentrated in developed economies since they emerged as a major economic process a century ago. The highly uneven influx of FDI into China is historically unique, however: while FDI was largely non-existent during the Mao era, China was one of the top recipients in the world, with US$290 billion of FDI, in 2013.Footnote 13 A central factor in this development was the formation of ‘Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in 1978, which in itself exemplifies and extends a consolidatory trend of SEZ formation in global economic history.Footnote 14 Hyper-mobile capital in search of low-cost and non-militant labour markets found the biggest such market of all in China. The result was a fast-growing inflow of FDI into China after the CPC nullified all geographical restrictions on FDI in 1992.

Because the Chinese economy was initially short of technological expertise and financial capital to drive industrialization, fully opening the FDI component in the capital account became a developmental strategy. It enabled foreign producers to move capital in and out of China relatively easily if their primary purpose is to invest in the production of goods and services (i.e. the so-called ‘concrete economy’). This in turn offers a fresh angle from which to write global monetary history as a geographically variegated process. The willingness on the part of CPC policymakers to embrace FDI represents a historical rupture from a national perspective (given its non-existence between 1949 and 1978) while it subsequently consolidated the global neoliberal project by reducing barriers to entry for transnational corporations and facilitating international trade.Footnote 15 The consolidatory process becomes complicated, however, because of a distinct continuity in the way the other two components of the capital account – ‘portfolio investments’ and ‘reserve assets’ – are regulated and managed.

Portfolio investment encompasses transactions in equity and debt securities. Equity securities refer to shares, mutual funds, and exchange-traded funds that usually denote equity ownership. The level of equity ownership that defines portfolio investment is less than the percentage required for controlling ownership in an entity. Debt securities include tradable instruments such as bonds and notes, debentures (long-term instruments), and money market instruments (short-term instruments such as treasury bills and commercial paper). A fully open portfolio component means that anyone, regardless of citizenship, could freely invest in or purchase these securities (usually denominated in the currency of the country that underwrites or issues these securities). Key contemporary examples of economies with highly open portfolio components are the United States, the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Switzerland. As it stands, the portfolio component in China remains highly insulated and only approved foreign institutional investors can invest in securities within Chinese markets.

The third component of the capital account, reserve assets, contains assets that can only be bought and sold by monetary authorities like the European Central Bank, the US Federal Reserve, and the People’s Bank of China (PBoC). This component primarily allows these authorities to finance trade imbalances, check the impact of foreign exchange fluctuations, and address other issues under the purview of the central bank. Regular interventions to manage the reserve assets thereby reflects a high degree of turbulence in both the current and capital accounts. A particular intervention in the Chinese context – which precludes full convertibility – is the ongoing absorption of all foreign currencies that flow into the country through trade or FDI and the issuance of RMB to buyers at prices the PBoC deems suitable. The end product is a large reserve asset component in the Chinese macroeconomic system (particularly US dollar holdings, the main trading currency), which is reallocated primarily through purchases of sovereign debt securities (particularly those issued by the US) as well as through the overseas financial investments of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Ironically, this reallocation is only possible because the economies receiving these Chinese purchases and investments have open portfolio accounts.Footnote 16

Research in economic history has demonstrated how a high degree of openness to portfolio investments – termed in economic parlance as ‘high elasticity’ – has been associated with both the causes and effects of financial crises over the past century.Footnote 17 It is also this openness, however, that leads to the increasing demand for currencies of the ‘open’ economies. Viewed against these developments, it is interesting to note that CPC policymakers actually believed it was necessary – and possible – to adopt full capital convertibility. At the Third Plenum of Fourteenth CPC Central Committee in 1993, the CPC announced its goal to ‘gradually make the RMB a convertible currency’.Footnote 18 After achieving current account convertibility in 1996, the CPC announced it would ‘gradually achieve RMB capital account convertibility’ at the Third Plenum of the Sixteenth CPC Central Committee in October 2003.Footnote 19 Such was the importance of this commitment, the attainment of capital account convertibility was included as a working target in the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2006-10) that was approved in March 2006.Footnote 20

These commitments were subsequently re-defined, however, when it became apparent that the CPC would not release its grip on the national economy’s capital account. The CPC’s persistent quest for absolute political control over the domestic economy after market-oriented reforms were launched in the 1970s means full exposure to foreign purchasing and investment decisions (including those that determine the price of the RMB) was untenable because it could destabilize the domestic financial system. At the same time, the CPC’s ambition to internationalize the RMB requires effective demand for the currency overseas; this demand would be weak if few international economic actors could invest their RMB holdings in equity and debt securities. Adding to the challenge of RMB internationalization is the CPC’s retention of a fixed exchange rate, which necessitates the management and redistribution of its reserve assets in ways that would not lead to the devaluation of these assets. In view of these developments, the-then PBoC Governor, Zhou Xiaochuan, proceeded to re-define capital account convertibility in an address to the International Monetary and Financial Committee (IMFC) in 2015:

It is worth noting that the concept of capital account convertibility has changed since the global financial crisis. The capital account convertibility China is seeking to achieve is not based on the traditional concept of being fully or freely convertible. Instead, drawing lessons from the global financial crisis, China will adopt a concept of managed convertibility. After achieving RMB capital account convertibility, China will continue to manage capital account transactions, but in a largely transformed manner, including by using macroprudential measures to limit risks from cross-border capital flows and to maintain the stable value of the currency and a safe financial environment.Footnote 21

Zhou’s comment underscores how the CPC views capital account convertibility as neither historically inevitable nor necessary for global economic integration. Not only is there no current supranational institution that enforces the compliance with a universal standard, debates on the necessity of full capital account convertibility have also become fierce amongst economists, the very inventors of this model. In an empirical analysis provocatively titled ‘Who Needs Capital Account Convertibility?’, Dani Rodrik argues that no correlation exists between the openness of countries’ capital accounts and investment amounts or their respective growth rates. For this reason, ascertaining the benefits of an open capital account becomes difficult. Conversely, in an argument consistent with the previously presented economic historical research on the intrinsic instability of openness to portfolio investments, Rodrik demonstrates how the costs of open capital accounts are regularly expressed through crises in emerging markets.Footnote 22 In the same year, Ross Levine and Sara Zervos published two studies that demonstrate how capital account liberalization had no effect on investments.Footnote 23 More recent studies on the unstable effects of open capital accounts on emerging economies have further affirmed these arguments.Footnote 24

That an ideal-typical model of capital account convertibility is not reflected in practice even as neoliberal hegemony expanded across the post-Second World War global political economy makes it ironic that this model is widely portrayed in academic and policymaking circles as a major precondition of an internationalized currency.Footnote 25 From a global historical perspective, the apparent objective requirement of full capital account convertibility only emerged after the installation of the US dollar as the global reserve currency. In other words, this development is at once global and specific to the dollar-centric system that is both difficult to replicate and evade. It corresponds with the constructions of national income accounting and the so-called ‘development’ expertise by statistically-minded economists to create a new economic world order.Footnote 26 Integral to these constructions were two mutually reinforcing processes, namely the formulation of 1) new methods of income calculation and comparison, which produced a sensational new view of the world as a place of enormous poverty, and 2) the belief that problems within this world could be solved by applying a limited set of policy recommendations to all economies.Footnote 27 National income accounting, with its emphasis on balance of payments to capture international monetary flows, and seemingly universal ‘developmental’ guidance based, explicitly and implicitly, on its constituent categories (e.g. government expenditure, savings, asset formation, etc.), thereby coalesced into and constituted a post-war political project to consolidate the new dollar-denominated monetary system under the (unproven) assumption that full capital account convertibility represents a more ‘efficient’ allocation of financial capital in the world markets.

As the next section will elaborate, this assumption is inapplicable to the highly regulated and quasi-insulated Chinese macroeconomic system. Hans Genberg, the previous chairman of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, puts this development in sharp perspective:

When the euro was introduced, there was much talk about how it might challenge the role of the dollar, and predictions have been made about when the euro will overtake the dollar as the premier official international reserve asset. More recently, with the emergence of China as a major economic power, the possibility that the renminbi will become a major international, or at least regional, currency has been mentioned. Viewing currency internationalisation as a race between competing currencies raises at least two issues: what determines the evolution of the international use of a currency, and whether there is a case for policy interventions to promote such use.Footnote 28

Genberg’s observation illustrates two crucial aspects of currency internationalization that will be evaluated in this article: the historical foundations of a currency and the practical purpose of promoting the usage of a national currency on a global scale. To this end, this article establishes a critical engagement with research that portrays currency internationalization as a competition for historically successive global supremacy.Footnote 29 It foregrounds, specifically, the assumption that only one anchor currency can exist, and that the emergence of other internationalizing currencies constitutes an implicit threat to that anchor. Whether this is the real purpose of RMB internationalization cannot be ascertained from a teleological vantage point, however. As Miriam Campanella puts it, ‘we may become blind to actual developments if we approach RMB internationalization in the same way as we discuss basic requisites of other fully-fledged reserve currencies’.Footnote 30 Instead, an important ‘actual development’ is the CPC’s path-dependent and spatially differentiated macroeconomic management since the founding of the PRC in 1949. RMB internationalization, as this article will demonstrate, is a direct outcome of this path dependence and spatial differentiation.

Well-developed within historical institutionalism, the notion of path dependence has become increasingly prominent in historical studies and the social sciences.Footnote 31 Arguably the most common definition of path dependence is the dependence of current and future actions/decisions on the outcomes of previous actions or decisions. As Scott Page puts it, path dependence ‘requires a build-up of behavioral routines, social connections, or cognitive structures around an institution’.Footnote 32 Path formation is commonly construed as an accidental outcome; a chance event. Central to this process is the eventual formation of institutional ‘lock-in’, whereby a practice or policy becomes effective or feasible because a large number of people have adopted or become used to this practice or policy. Any drastic alterations to the path, even in the face of inherently superior alternatives, would thus encounter resistance from groups of ‘locked in’ actors whose interests would be compromised by the proposed changes.

A focus on the interaction between RMB internationalization and inherited developmental pathways such as the previously introduced fixed exchange rate regime offers a unique prism through which to examine both the effects of Chinese central planning since 1949 and, paradoxically, the relevance of pathways first instituted by the CPC’s arch enemy at the time: the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party 国民党).Footnote 33 At one level, path dependence explains how attempts to expand the RMB’s global circulation proceed in tension with established institutions at different levels. In exchange for retaining some Mao-era regulatory policies such as absolute state control over the currency price and supply of RMB overseas, more liberal reforms such as encouraging unregulated offshore trading in RMB are instituted. The paradoxical outcome therein lies in the dependence of change – including what appears to be moments of radical ruptures – on continuity.

At another level, however, the conceptual application of path dependence should be mindful of some of its biggest problems. Page identifies a lack of emphasis on the ‘build up’ to the formation of path-setting institutions.Footnote 34 This corresponds with Guy Peters and others’ observation of a tendency in research on institutional path dependence to accord history a logical trajectory, or ‘retrospective rationality’, such that available alternatives and political conflicts that occurred alongside more ‘visible’ historical processes are neglected.Footnote 35 It is important to be cognizant ‘that prediction of persistence does not help at all in understanding institutional change’.Footnote 36 These insights collectively foreground two interrelated blind spots in the historical institutionalist literature on path dependence that might obscure the historiography of RMB internationalization.

First, it is often unclear how the production of a specific ‘path’ within the national level evolves in tandem with changing global connections. Second, institutional persistence at the national level could entail changing policies and practices to accommodate changing engagements with the global economy. In other words, institutional change could be the precondition of continuity. Taking these two blind spots into consideration, this article is careful not to reduce RMB internationalization to a linear, national-level historical process that is exclusively derived from the post-1978 market-oriented reforms first discussed above.Footnote 37 Rather, the post-Mao Chinese government has been working at various levels – albeit on a tentative and, in some cases, contentious basis – to develop a currency that corresponds simultaneously to the demands of transnational capital circulation (an intrinsic aspect of global capitalism) and financial repression (an intrinsic requirement for consolidating and sustaining CPC rule).

Moving forward into the details of China’s global economic currency internationalization history, the overarching objective of the next three sections is thus to historicize contemporary RMB internationalization not as a l’art pour l’art exercise in chronological exposition, but to identify the historical-geographical conditions that shaped the RMB’s ongoing and, in many ways, capricious internationalization. Following this approach, these three sections collectively explore why, despite a series of policy changes during the post-Mao era that injected more flexibility into currency holdings and circulation, has the CPC refused to allow full capital account convertibility until today and why this is possible in a world of otherwise highly internationalized currencies.

In the following three sections, speeches by CPC leaders and others, policy documents, and Chinese-language journals and books have been collated, translated, and then assessed through an historical analytical framework that examines how path dependence is entwined with the processes of ruptures, consolidations, and continuities. Drawing from these materials, these sections will present the contradictions, tensions, and struggles of the RMB’s formation and evolution across three historical moments. This analytical approach foregrounds both the rationale of recent reforms in China’s financial system, with RMB internationalization at their core, and their shifting historical-geographical conditions. In turn, it underscores the importance of an historically grounded rather than a predictive and teleological framework for understanding currency internationalization.

Moment one: the RMB as a ‘unifying’ tool

The RMB was first issued on 1 December 1948 by the PBoC. Relative to the contemporary rationale of circumventing US dollar hegemony through RMB internationalization, this issuance was ironically facilitated by the USA. The CPC was engaged at the time in a seemingly intractable civil war with the KMT. The KMT had generated a hyper-inflationary economy between 1946 and 1948 through the unrestrained supply of fabi (法币), a fiat currency not tied to any commodity. To rescue the currency system and mitigate social unrest, an alternative ‘commodity currency’ – the gold yuan (jinyuanquan 金圆券) – was launched in August 1948.Footnote 38 Just like the RMB today, the KMT sought to peg the new currency to the US dollar (the ‘commodity’, with the dollar being ‘as good as gold’ given its placement on the gold standard) but was unable to build up dollar reserves.

This lack of reserves was due not only to a lack of trading surpluses, which were an outcome of the-then ongoing civil war and the preceding resistance against Japanese occupation during the Second World War, but more crucially due to an unwillingness of the US government to increase dollar loans to Chiang Kai-shek’s government.Footnote 39 In other words, the US government lost faith in the KMT even before the KMT’s own supporters within mainland China, and it was this vote of no confidence that broke its last line of economic defence.Footnote 40 The stage was then laid for the RMB to become the currency of ‘new China’ – the currency that would now come to be regarded as the potential successor to the US dollar.

Understanding the contemporary purpose of RMB internationalization entails an understanding of its role as a political tool in the first instance. According to the accounts in 1947 and 1948 from two leading CPC cadres, Dong Biwu and Liu Shaoqi, currency variations were also evident within the Communist-held areas already ‘liberated’ from the KMT, which consequently intensified the necessity for a ‘unifying currency’ (tongyi huobi 统一货币).Footnote 41 The PBoC was therefore established to undertake this task. Its role in rolling out the new currency was officially announced in the CPC’s then-fledgling (and now preeminent) newspaper, the People’s Daily, on 6 December 1948.Footnote 42 Naturally, the currency first issued by the ‘people’s bank’ would be termed the people’s (renmin人民) currency (bi 币). Mao was unequivocal about the significance of this currency: ‘The people now have their own armoury, their own political authority, their own land, now they even have their own bank and currency, this then truly defines a republic with the people as their own masters!’Footnote 43

Mao’s comment is central to understanding the national-level historical impact of the RMB’s issuance. By virtue of establishing a new central bank and national currency that encompassed what was then a spatially fragmented ‘China’, a radical rupture emerged and added to the confusion and chaos caused by the short-lived and ill-fated gold yuan. At the same time, however, its emergence offered an opportunity to consolidate the geographical impact of nascent CPC rule: economic transactions were previously predicated on the use of multiple and often hyper-inflationary currencies in territories such as Manchuria, land held by feudal warlords, KMT-controlled regions, and foreign concessions, etc. A currency that could be universally accepted would thereby legitimize the CPC’s power by acknowledging the CPC’s legal right to determine exchange value within this newly established state. Interestingly, the RMB represented a continuation of the fiat currency system – more specifically, that of the fabi that was not backed by commodities – of ‘old China’ under the KMT. Rather than overhaul the KMT’s hyper-inflationary currency system, this system was recalibrated in 1955 through a unilateral revaluation of 1 new RMB to 10,000 old RMB. The revaluation established the monetary platform for the CPC to roll out its variant of state capitalism that still exists in a geographically reconfigured form today.Footnote 44

Herein lies a clear distinction to currency use between the CPC and the KMT: Mao was keen to ensure there would be no new currency to replace the RMB even in the presence of inflationary surges triggered by excessive money creation, which occurred during his tenure and peaked at 16% in 1961.Footnote 45 In a telling conversation with a representative party of the Venezuelan Communist Party in 1964, Mao puts this approach in perspective: ‘An increase of 30% of the people’s living costs may not be felt as a major problem by the majority…a currency problem is not just about depreciation, it is about abolishing one and issuing another’.Footnote 46 This willingness to create money on demand, a common approach across the global system of capitalism over the past century, and yet ensure currency acceptance by the populace, would underpin the CPC’s subsequent macroeconomic management.

An additional consolidatory aspect of the RMB’s growth as a national currency is the highly internationalized nature of Chinese state capitalism from the outset. Tied intimately to the Soviet Model and connected through trade plans and technological sharing with the broader ‘socialist world economy’, state-driven capital accumulation was predicated on currency exchange rather than an abolishment of currency usage in toto.Footnote 47 A ‘one price rule’ was established for items available for sale – i.e. all trading partners would buy and sell a particular product at the same price – and these were denominated in the Soviet ruble, with the State Bank of the USSR serving as the clearing house. Chinese authorities therefore spent much of the 1950s trying to establish exchange rates between the RMB and ruble, with common disagreements on the precise value because the RMB was not backed by gold while the Soviet government had placed the ruble on its own gold standard since 1950.Footnote 48

To accumulate capital for trade and retain trading partners’ confidence in the value of the newly-minted RMB (which precluded large scale monetary expansion within a short period), the CPC relied primarily on an accumulation approach imported from the Soviet system: the ‘price scissors’ mode of accumulation (jiage jiandao cha 价格剪刀差). Under this approach, capital-intensive heavy industries that did not require a large labour power support base were located in the cities. To ensure these industries could receive a steady stream of funds and/or raw materials, surplus laborers and their families (totalling 80% of the population) were immobilized in the rural People’s Communes (renmin gongshe 人民公社).Footnote 49 This precluded the formation of autonomous ‘price signals’ for labour power; labour power could not move to locations that offered the highest wages, while employers could not use wages to attract their desired workers.

The accumulation process was reinforced through the administrative removal of price-setting powers by the peasants. To this end, the CPC institutionalized the ‘unified purchase and sale’ (tonggou tongxiao 统购统销) system in 1953, through which a monopsony purchased agricultural products from all communes at very low prices. The products were then used to sustain workers in the cities and/or used as raw materials in industrial production. The costs of paying industrial workers and of raw materials were consequently suppressed. At the same time, the state, acting as a monopolistic supplier, generated high profits by raising the prices of industrial products (e.g. machines, chemical fertilizers, textiles, etc.) that would then be re-sold to the communes. By accepting state-suppressed prices for their agricultural products and paying higher prices for goods produced by urban-based industries, peasants were effectively subsidizing national-scale industrialization in China. Specifically, the role of rural labour power became (and remains) the basis for the CPC to define and capture value.

In tandem with this accumulation approach was an emergence of ideological differences within the CPC regarding the role of currency exchange. As Mao implemented a ‘great leap’ towards communism through the absolute collectivization of resources and labour power in the late 1950s, Chen Boda, one of Mao’s closest associates at the time and a key interpreter of ‘Mao Zedong Thought’, launched a theory entitled ‘currency is of no use’ (huobi wuyong lun 货币无用论) and sought to experiment with vouchers that could fully replace money.Footnote 50 While Chen’s vision was regarded as extreme leftism, his suggestion was taken into consideration, modified, and then implemented nationwide in the communes, with workers compensated with ration tickets and paid a small proportion of their wages in RMB.Footnote 51

This juxtaposition of currency negation and embrace was evident most markedly during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76): at the same time as campaigns were launched to denounce ‘being led by profits’ (lirun guashuai 利润挂帅) and to portray ‘currency as the source of class differences’ (huobi shi chansheng jieji de genyuan 货币是产生阶级的根源), the CPC continued to expand monetary supply domestically and sustained a substantial banking presence in Hong Kong – and, by extension, its connection to the dollar-centric monetary system – throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Specifically, the Mao leadership not only retained a nominal RMB-dollar exchange rate, but also enabled what Catherine Schenk terms ‘considerable continuity in the banking relations between Hong Kong and Mainland China’.Footnote 52 While most foreign banks withdrew from China during the Mao era, the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (HSBC) maintained a presence in China, and by the early 1970s, thirteen PRC-controlled banks with a total of fifty-five branches were established in Hong Kong, holding more than HK$2 billion (US$354 million) in deposits.Footnote 53 Quite simply, Mao Zedong’s ideological commitment to create a communist heaven proceeded in tandem with sustained engagement with the global system of capitalism via Hong Kong, which was to become the launchpad of RMB internationalization after the mid-2000s. For this reason, Deng Xiaoping was able to re-introduce market-oriented rule in 1978 without much of the currency-related turbulence that greeted Mao in the late 1940s. (See also section six, below.) A consolidated and globally connected national monetary system was already in place.

Moment two: the consolidation of RMB value after 1994

While market-oriented developmental initiatives were implemented to much enthusiasm across China in the early 1980s, it was accompanied by a series of inflationary surges that triggered social unrest.Footnote 54 These surges were caused primarily by two factors. First, the Chinese state began adjusting prices for many products upwards towards levels that would normally ‘clear’ in markets (i.e. state prices were generally lower than market prices and hence needed upwards adjustments). Second, there was a direct connection between money supply and government spending: with government spending increasing in part to finance new investments by state-owned enterprises and in part to sustain inefficient operations, so did money supply.Footnote 55

These developments collectively generated instability in the national current account and a concomitant depreciatory pressure on the RMB during the 1980s and early 1990s. The Chinese national economy generated its worst deficit of more than US$11.6 billion in 1993, with the RMB known to be trading at between eight and nine yuan to the US dollar in the ‘private’ (i.e. underground) markets vis-à-vis the official rate of 5.80 yuan to a dollar.Footnote 56 Against this backdrop, Zhu Rongji, the-then First Vice Premier who was in charge of resolving economic issues and who was known to be advised by ideologically diverse economists and think tanks, decided to introduce a series of policies that ruptured institutional practices inherited from the Mao era.Footnote 57 Two of these policies transformed the domestic financial structure and the value of the RMB: the accordance of central banking autonomy to the PBoC and the convergence of RMB exchange values.

To free the PBoC from pressures by local governments and SOEs to generate loans through excessive credit creation, the ‘Law of the People’s Bank of China’ (中国人民银行法) was proposed in 1994 and implemented in March 1995.Footnote 58 This legislation fundamentally severed the positive relationship between monetary supply and budgetary demands at the local level. Launched in tandem with a new ‘tax sharing institution’ (fenshui zhi 分税制) that essentially shifted fiscal resources ‘upwards’ towards Beijing, the capacity of local governments and SOEs to overheat the economy was further weakened.

Additional steps to consolidate the central government’s control over the 1978 reform process were implemented in 1994 and 1995. Two ‘dual track’ currency systems that backed the reforms of 1978 were phased out via their merger by 1995. First, the CPC decided to abolish a dual track currency system instituted in April 1980 that permitted the use of RMB by Chinese citizens while foreigners were mandated to use foreign exchange certificates (FECs) ‘at designated places’.Footnote 59 FECs were nominally of the same value as the RMB and were intended for foreigners living in or visiting China to purchase consumer goods, many of which were sold at specialist shops such as ‘Friendship Stores’ that were not accessible to locals. Its associated, though not officially publicized, objective was to prevent foreign merchandise and currencies from flooding the domestic market.Footnote 60 Because exchange rate levels continued to be pegged unrealistically vis-à-vis the major international currencies until 1994, the cost of these certificates was invariably higher than if the RMB were freely traded.Footnote 61 These regulations therefore precluded large-scale capital inflows from abroad. The full withdrawal of FECs by 1 January 1995 meant the RMB became the sole currency of use for foreigners in China, a major step towards current account convertibility (i.e. the freedom to convert currency for imports and exports).

The second dual track system to be streamlined was the readjustment of the official RMB exchange rate to levels more in line with existing ‘market rates’. Although the CPC previously maintained its official rate, it began allowing firms to trade the RMB in designated ‘forex adjustment centres’ (外汇调剂中心) since 1986.Footnote 62 Forex trade was expanded after the PBoC founded the China Foreign Exchange Trade System (CFETS; 中国外汇交易中心) in April 1994. A distinctive feature of the CFETS was the official movement from centralized price-setting by the PBoC to an arrangement that enabled the RMB to be traded at prices determined by ten international banks.Footnote 63 The number of participants also increased: apart from domestic commercial banks and their authorized branches, non-banking financial institutions such as insurance companies, securities companies, fund management companies, financial companies, as well as foreign financial institutions authorized to engage in RMB business, were allowed to trade.

Concomitant with the establishment of the CFETS in 1994 was a one-off re-adjustment of the RMB value from under 5.8 RMB to the US dollar to 8.7 RMB. This ushered in a period of ‘strict pegging to the dollar’, as Zhu Rongji puts it, from 1994 to 2005.Footnote 64 Tellingly, Zhu is keen to emphasize that the new exchange rate did not represent a devaluation:

The combination of exchange rates took on good effect, it was a vital aspect of our financial reforms. Doing so required huge determination and involved risks. Currently there are people who viewed our 1994 policy as a massive devaluation for the RMB, as pricing the RMB too low. What they did not understand was the situation involving two exchange rates, with a higher focus on adjusting prices in the [private] foreign exchange market. Import and export depended on adjusting the foreign exchange rates [to levels acceptable by foreign firms], hence in actuality we did not experience a massive devaluation when the rates were merged. Rather, the RMB appreciated [nominally] from 8.7 RMB to 8.28 RMB to a dollar [and against the black market rates of between 9 to 11 RMB to a dollar].Footnote 65

At one level, these developments constitute a historical rupture because they marked the first instance since the founding of the PRC that exchange rates were aligned to levels determined by key actors in international money markets. From a global historical perspective, the US dollar peg also marked the complete about-turn in China’s relationship with the United States, a country that was ridiculed by the Mao regime as the emblem of imperialism. Chinese macroeconomic policies now depended on the inflow and retention of US dollars and, hence, they contributed to the continuity of American hegemony within the global political economy. Zhu’s approach was of historical significance because it officially re-established a Chinese currency’s direct connection to the US dollar last seen during the short-lived era of the gold yuan. At another level, these ruptures collectively consolidated the CPC’s macroeconomic control after the financial instability of the 1980s and early 1990s. Indicative of a commitment to non-inflationary monetary and fiscal policies, the dollar peg set the path for current account convertibility, which was actualized in 1996, and made it more straightforward and attractive for foreign investors to operate in China.

Zhu Rongji’s decisive interventions further re-defined the international role of the RMB: the shift to a US dollar peg was meant to augment international confidence in a financial system that was teetering on the brink of collapse, yet it coincidentally became a political-economic asset when the Asian financial crisis unfolded in 1997. While many Asian economies suffered from currency volatility vis-à-vis the US dollar and had to introduce devaluation as a desperate monetary policy response, the RMB gained in value because of its peg to the US dollar. As China’s trading partners found it more expensive to purchase Chinese goods, there was high expectation that the Chinese government would aim for competitive devaluation. Quite unexpectedly, however, the Chinese government generated goodwill amongst its Asian neighbours – with a tacit aim of lubricating its entry into the WTO – by deciding against devaluation.Footnote 66 This was arguably the first instance since the formation of the PRC that CPC control over the domestic financial system, albeit here in the form of a US dollar peg, generated distinct macroeconomic effects at the international level.

Moment three: RMB internationalization as a response to the 2008 global financial crisis

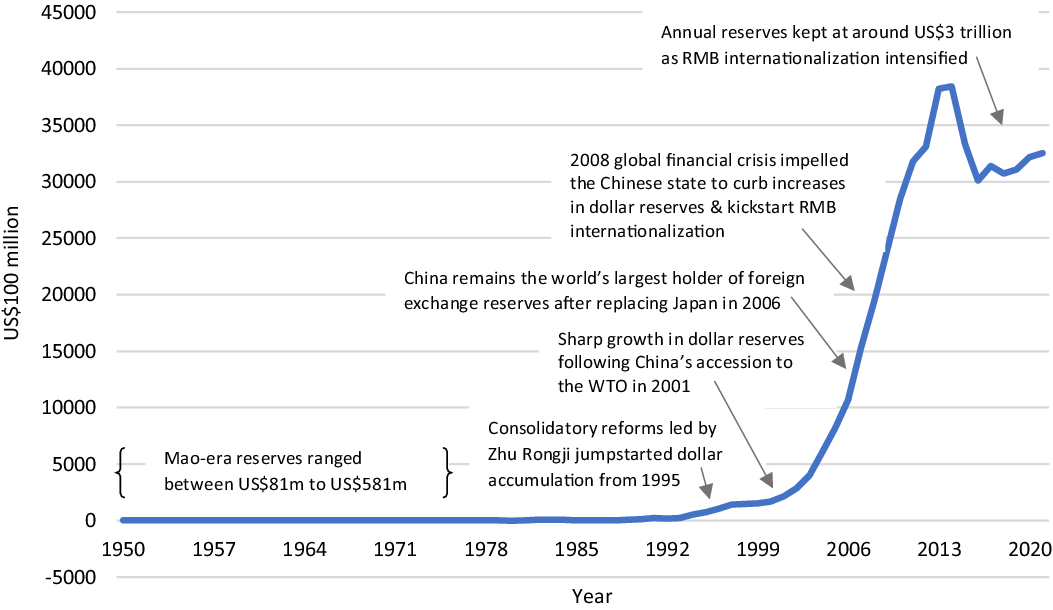

RMB internationalization attracted attention from scholars and policymakers when the Chinese government announced trials for cross-border trade settlements in Shanghai and Guangdong in April 2009. Details of these settlements involved ten Southeast Asian countries and were subsequently published in July 2009.Footnote 67 Further moves to promote the use of the RMB came through 1) the designation of offshore RMB centres (人民币离岸中心), and 2) the China-driven geo-integration programmes known as ‘Go Abroad’ and the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’. A growing lack of confidence in the value of the US dollar after the 2008 global financial crisis triggered the move towards this further internationalization of the RMB. As Figure 1 shows, the Chinese State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) began to accumulate significant amounts of US dollars after Zhu’s reforms. Those reserves grew rapidly after China’s accession to the WTO in 2001. Yet because the US dollar value had gradually declined and because that decline worsened when the US government decided to resolve the 2008 crisis through ‘quantitative easing’ (i.e. money creation), the-then Chinese Premier, Wen Jiabao, famously expressed in 2009 that he was ‘definitely a little worried’.Footnote 68 What followed this ‘worry’ was a proactive attempt at encouraging the global use of the RMB.

Figure 1. China’s foreign exchange reserves in US$, 1950-2021.

Source: China State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) statistics, available at: https://www.safe.gov.cn/en/ForexReserves/index.html

Author’s compilation and diagrammatic expression.

It should be noted, however, that the 2008 global financial crisis offered an opportunity for the Chinese state to reflect on and recalibrate the large-scale accumulation of reserves since Zhu Rongji’s financial reforms of the mid-1990s. That the Chinese state could react, with bilateral settlements, to what it perceived as an ill-conceived US government handling of the financial crisis in 2009 was in large part because China’s foreign policy had created the economic-geographical conditions for internationalization during the preceding decade. Since the late 1990s, the RMB was used by firms and individuals in geographically proximate economies such as Hong Kong, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Mongolia. The 2009 RMB-denominated trade settlement pilot scheme built on a related development in the same year: China was a signatory of the Chiang Mai Initiative in 2009, a multilateral currency swap agreement involving the ten nations of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Japan, and South Korea. This correspondingly promoted small-scale, cross-border trade between China and its neighbours by increasing the supply of RMB for trade settlements.

Concomitant with the rise in RMB usage outside China was the establishment of what is now known as ‘offshore RMB centres’. This development did not occur in 2009, but emerged from the PBoC’s gradual and experimental approach to establishing an offshore RMB capital market in Hong Kong in 2004. Limited RMB circulation was permitted in Hong Kong at the time, with an 100% required reserve ratio on deposits. This made credit creation impossible as the clearing bank in Hong Kong, the Bank of China, had to transfer all of the reserves back to the branch of the PBoC in Shenzhen, the city located just across Hong Kong’s border with the Chinese mainland.Footnote 69 RMB-denominated bonds issued in Hong Kong – widely referred as ‘dim sum bonds’ – were subsequently permitted in 2007, and this was then followed in 2010 by experiments with interest rate liberalization by allowing banks in Hong Kong to issue loans to businesses based in a specially designated territory within neighbouring Shenzhen-Qianhai New Area.Footnote 70

To enhance offshore-onshore connections, a primary ‘bridging mechanism’ in a designated RMB offshore trading centre was the granting of licenses to companies that qualify as a ‘Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor’ (RQFII). RQFII-licensed firms could channel RMB funds raised in the offshore trading centre (e.g. Hong Kong, London, and Singapore) into securities markets within mainland China.Footnote 71 Offshore RQFII holders (typically multinational banks like HSBC and Standard Chartered) may issue public or private funds or other investment products using their allocated RQFII quotas. Non-RQFII products in the offshore RMB centres are geographically delimited to those centres, e.g. RMB-denominated bonds issued within Hong Kong or London, RMB bank deposit accounts, etc. For this reason, these products are significantly less attractive because they cannot be re-invested into non-financial sectors within the Chinese economy.

At the onset of its launch in August 2011, the quota for reinvestment was set at a relatively low 20 billion yuan (∼US$3.3billion).Footnote 72 Subsequent demand saw the quota revised multiple times before the programme lost popularity vis-à-vis the emergence of more straightforward investment channels such as Stock Connect (which allows trading of stocks between Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Shenzhen without licenses), Bond Connect (very similar to Stock Connect), and the China Interbank Bond Market (CIBM, which opened up to foreign investors in 2015, a year before the launch of Bond Connect).Footnote 73 SAFE eventually announced in September 2019 that the RQFII scheme would be scrapped.Footnote 74

While these initiatives triggered an increase of RMB flows overseas, it has not jumpstarted a sharp growth in RMB usage after more than a decade of explicit internationalization. According to the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), the RMB’s share of global payments stood at 2.2% in July 2022, substantially lower than the Euro (35.49%) and the US dollar (41.19%).Footnote 75 The lack of full capital account convertibility arguably contributed to the RMB’s limited uptake offshore. Path dependence is very much evident in this regard: the Chinese government continues to wield huge control of the domestic capital market despite the institution of market-oriented reforms.Footnote 76 It has consolidated the holdings of its state-owned enterprises (at both central and provincial levels), retained high foreign barriers to entry to the two domestic stock exchanges, and influenced credit provision through policy directives to the major banks, which are state-owned. Corresponding to Zhou Xiaochuan’s re-definition of capital account convertibility in 2015 (quoted above in section two), these developments collectively reflect a lack of opportunities for offshore RMB holders to invest in sectors and channels that could generate both short-term (e.g. stocks, interest rate arbitrage) and long-term yields (e.g. real estate, RMB-bonds issued within China).

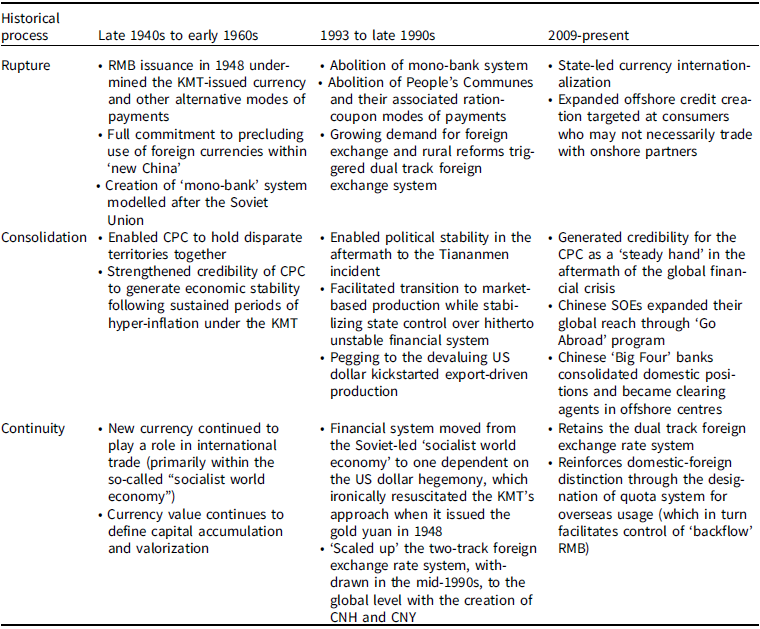

Table 1 provides an overview of the connections between the three historical moments of RMB internationalization. The analytical approach developed in the previous three sections has uncovered three rolling historical moments of RMB internationalization that build on one another like a palimpsest. Instead of the widespread assumption of a radical rupture in China’s economic policies after 1976 and especially so with the 1978 and 1979 reforms, an analytical approach that examines the connections between ruptures, consolidations, and continuities reveals enduring historical layers of the CPC’s insistence on absolute political control over the domestic financial system. The unification of currency rates, currency types, and disparate economies was and remains the motif of this control. Despite expanding the global usage of the RMB, domestic conditions remain ensconced within a control-centred regulatory logic extending as far back as the 1950s.Footnote 77 And it is this entwinement with the past that entails an interpretation of RMB internationalization as historically grounded and, by extension, distinct from those of other globally prominent currencies, namely the US dollar, British pound sterling, Japanese yen, and the Euro. The next section will critically assess the global historical significance of this process with the emergence of the dollar as the current global reserve currency.

Table 1. The evolution of the RMB: three key moments

Source: Author.

The global historical significance of RMB internationalization: a comparative overview

All the three critical moments of RMB evolution introduced in this article were linked to the dollar-centric global monetary system in different ways. While the RMB’s domestic and international role has changed substantially, a distinct continuity is apparent: a willingness on the part of the CPC to accumulate and transact in dollars. As section three demonstrated, the Mao leadership chose to remain coupled with the global monetary system (via PRC-owned banks in Hong Kong) during the height of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s and early 1970s even though this simultaneously went against the prevailing campaign against ‘capitalist roaders’. And this continuity would play an important role in Deng’s market-oriented reforms in the 1980s (which drew many investors from Hong Kong) and Hong Kong’s role as a conduit for RMB internationalization after sovereign rule of Hong Kong was handed over to the PRC in 1997 (as discussed above). From a global historical perspective, then, the emergence of RMB internationalization occurred against a backdrop of sustained engagement with the dollar-centric monetary system – it reflects an alignment with rather than a challenge to the dollar-centric pathway.

To speak of the RMB as a ‘challenge’ to the US dollar would be to think in what Benn Steil and Manuel Hinds term ‘monetary sovereignty’: nation-states compete to impose sovereign power at the global scale through currency internationalization.Footnote 78 Yet, the well-researched history of the dollar’s transformation into the global reserve currency indicates it was an outcome of a unique combination of historically-specific characteristics. These characteristics emerged both at the domestic level in the US, particularly the tenuous path towards the formation of a central bank, the Federal Reserve, and at the global level, particularly after the British government abandoned the sterling’s peg to gold and paved the way for the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944.Footnote 79 In other words, the emergence of the US dollar as the global reserve currency was less a case of competition between the USA and other states for monetary sovereignty and more a case of a coalescence of favourable domestic and international factors.

As Table 2 shows, the Bretton Woods Agreement was a moment of global historical rupture because it marked the official recognition of the dollar as the global reserve currency. This recognition was possible only because it consolidated the-then fledging gold standard and offered much needed stability to many countries that were experiencing the debilitating economic effects of the Second World War. Where RMB internationalization is concerned, however, there was no such rupture: it was a unilateral process by the Chinese state to address the contradictions of sustaining a fixed currency regime within a context of global economic integration.

Table 2. RMB internationalization from a global historical perspective: a comparison with dollar internationalization

Source: Author.

The role of offshore centres to drive currency internationalization is a geographically distinct process that underscores fundamental differences in the global historical significance of the dollar’s and RMB’s internationalization trajectories. Contrary to the nationally-driven attempt to internationalize the RMB through Hong Kong as the primary clearing site, the rise of London as a Eurodollar capital market was initially an attempt by Midland Bank, which originated in the UK, to achieve regulatory arbitrage through seeking US dollar funds to then exchange for sterling (and hence sidestep the tight monetary controls within the UK).Footnote 80 The establishment of non-resident convertibility in 1958 precipitated the involvement of American and Japanese banks that were seeking regulatory and price arbitrage in and through London. The Eurodollar market grew primarily because 1) the US dollar was increasingly adopted as a currency for loans, swaps and trade settlements, which increased the dollar supply and deposits outside the US; and 2) because there was simultaneously strong demand for the overseas dollars by American banks facing liquidity challenges within the US.Footnote 81 These developments jointly engendered a pathway during the 1960s that both enabled and encouraged transnational dollar flows, with the first major Asia dollar market subsequently appearing in Singapore in 1968.Footnote 82

With reference to Table 2, the proliferation of offshore US dollar markets in the 1960s and 1970s consolidated the dollar’s role as a post-Second World War global reserve currency by creating new trading opportunities that were beyond the regulatory reach of the issuing country (the USA). Such was the significance of this consolidatory effect that the decision by Richard Nixon, the-then US President, to de-couple the dollar from the gold standard in 1971 did not trigger an anticipated global financial instability wherein dollar holders would rush to ‘cash in’ dollars for gold and search for an alternative reserve currency. Indeed, the possibility – or, more precisely, the fear – of a ‘gold run’ on the Federal Reserve was a major factor that underpinned Nixon’s 1971 decision. Paul Volcker, the former US Federal Reserve Chairman who played an instrumental role in the US government’s push to break away from the Bretton Woods Agreement, noted in an un-dated interview during the 2000s that the outcome of the so-called ‘Nixon shock’ was unexpected: ‘There was great irony…People were more willing to hold dollars that weren’t backed by gold than they ever were willing to hold dollars that were backed by gold.’Footnote 83 This ‘irony’ suggests the 1971 decision marked a true moment of global historic significance – the world’s faith in the credibility of gold as the backer of US dollar value effectively shifted to a faith in the credibility of the US government as the backer of this value.

The crucial point here, as the previous three sections demonstrate, is that the RMB internationalization process also reflects this faith in the US government. Attempts to stimulate greater RMB usage in offshore centres like London and Singapore are fundamentally predicated on confidence in the RMB’s dollar peg. Insofar as the Chinese central government continues to accumulate large dollar-denominated reserves while permitting offshore RMB holders to transact through the current rather than the capital account, RMB internationalization would not engender a moment of rupture in global monetary history. What it demonstrates, rather, is the CPC’s path dependence on the dollar-centric global monetary system that in turn sustains its absolute domestic financial control (see Table 2). All signs are suggesting, indeed, that this national-level continuity is the overarching goal of RMB internationalization.

Concluding reflections

A currency, currency exchange, and its related institutions are neutral; it serves whoever controls it. – Mao Zedong, 1974Footnote 84

Much has certainly changed since Mao’s passing in 1976. A fully-fledged banking system now stands apart from the fiscal system in China, and macroeconomic governance is entwined with global capital markets, particularly those of sovereign bonds. At the same time, the persistence of many aspects of Mao-era regulatory rationale problematizes the possibility of a neat and linear periodization of the global political economy as existing in a neoliberal epoch: the banking system in China is dominated by state-owned banks that continue to direct much needed financial capital to state-owned enterprises that are increasingly re-investing this capital globally; foreign capital inflows and outflows remain tightly scrutinized; leaders of the interest rate-setting PBoC are appointed by the CPC; and the state actively intervenes in stock exchange trading, which is quasi-insulated vis-à-vis the global financial market to begin with.Footnote 85 Through these rigorous controls of both financial demand (through state-owned enterprises) and supply (through credit creation from the state-owned ‘big four’ banks and large-scale stimulus packages underwritten by these banks), the Chinese government has been able to prevent crisis-induced debt-deflation typically associated with capitalist economies.Footnote 86 In doing so, it could sustain its sovereign power over the PRC.

This article has foregrounded this path dependent process through an analytical approach that traces and critically examines the ruptures, consolidations, and continuities in the RMB’s national and international roles. As the three moments presented above demonstrate, the RMB’s evolution from a unifying national currency to one that is increasingly used in international trade reflects institutional continuities at both the domestic and global level. Domestically, state monopoly of the domestic financial system and the retention of a quasi-fixed exchange rate system entails consistent monitoring and intervention by the CPC. This is the main reason why the capital account in China cannot be fully convertible; it is why there remains a foreign-domestic or onshore-offshore distinction for a currency that is supposed to be(come) ‘international’. Globally, as the preceding section demonstrates, the RMB’s evolution is underpinned by engagements with rather than exclusions from a dollar-centric global monetary system. It is this path dependence that precludes an interpretation of the RMB’s growing global usage from a teleological perspective. Foregrounding these national-global relationships offers a new dimension to William Kirby’s important argument that ‘the history of the PRC is simply incomprehensible without a strongly international perspective’.Footnote 87

Specifically, this article has shown how the RMB evolved in and through a Chinese financial system that experienced changing relations with the international economy. The contexts of these three moments were very different, to be sure: Mao was developing a system that was capable of engaging the ‘socialist world economy’ in the 1950s; Zhu Rongji was confronted with the inflationary pressures engendered by deepening global economic engagements; while the Hu Jintao regime was addressing the crisis-prone tendencies of intensifying financialisaton. Yet one aspect remains unchanged: absolute CPC control remains the paramount goal of macroeconomic management in China. If anything, then, the historically grounded examination of RMB internationalization offers an important prism through which to identify and explain why the process to sustain CPC rule now involves controlling national currency use at the global scale.