Niemann-Pick disease type C (NPC) is a rare autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder with pathogenic mutations in either the NPC1 gene on chromosome 18 (95% of cases) or the NPC2 gene on chromosome 14 (5% of cases). Reference Patterson, Mengel and Wijburg1 The age of onset and clinical presentation of NPC is highly variable, ranging from a perinatal presentation with rapidly progressive acute liver or respiratory failure to rare adult-onset chronic progressive neurodegenerative form.

The overall incidence of NPC is 0.35–2.2 per 100,000. Reference Vanier and Millat2 However, the incidence and clinical presentation in adults has not been well delineated with only a few case reports and case series available in literature. We report five adult-onset NPC cases from India, presenting with various movement disorders.

An eighteen-year-old male presented with gradually worsening academic performance and behavioral disturbance for 3 years (Case 1). He was first evaluated at 15 years of age, when he had left upper limb dystonia with mild cerebellar dysfunction along with declining scholastic performance. At 18 years, he had further decline in his cognitive and balance troubles with worsening dystonia progressing to left hemi-body (Video 1) with facial and perioral involvement. Development of myoclonus, vertical supranuclear gaze palsy (VSGP) (Video 2), and splenomegaly led to the suspicion of NPC with an NPC suspicion score (NPC-SS) of 140.

Brain MRI showed nonspecific findings of mild T2/FLAIR hyperintensities in bilateral posterior parietal lobes. Bone-marrow aspiration demonstrated foamy macrophages. Clinical exome sequencing showed compound heterozygous variants in the NPC1 gene. Table 1 summarizes the phenotypic characteristics and investigations, including exome sequencing of our patients.

Table 1: Clinical characteristics and investigations of patients with NPC

ACMG: The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; LP: Likely pathogenic; P: Pathogenic; VUS: variants of uncertain significance.

* Clinical exome sequencing was performed in all the five cases (It covers 8332 genes including the most relevant disease- associated genes from OMIM, HGMD, Clinvar and Swisswar).Sanger confirmation was done for all the novel variants.

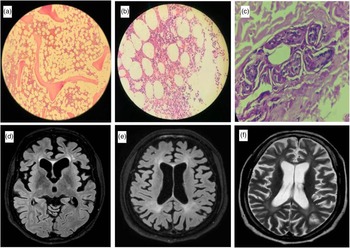

A 42-year-old female had a gradually worsening difficulty in looking downwards and upper limb tremors since the age of 25 years (Case 2). After 8 years of symptom onset, she developed gradual apathy, withdrawal, and memory loss along with bradykinesia, dysarthria, and urinary incontinence. The patient’s elder sister had a similar cognitive disturbance with onset at 22 years and wandered off from home after 5 years of disease onset. First examined at the age of 42 years, the patient had an MMSE score of 14/30 with predominant frontal dysfunction. She had slow saccades, broken pursuits, and VSGP involving downgaze more than upgaze. The examination also revealed bradykinesia, upper limb rest, postural and intention tremors, hypophonia, and unilateral foot dystonia along with bilateral upper limb choreiform movements with cortical myoclonus in distal upper limbs. Bone marrow aspiration showed abundant foamy histiocytes (Figure 1a, b), and skin biopsy showed perivascular histiocytic infiltration (Figure 1c). MRI brain showed marked frontal predominant atrophy (Figure 1d). Exome sequencing showed a novel homozygous variant in exon 3 of the NPC2 gene (Table 1).

Figure 1: Bone marrow aspiration of case 2 showing foamy macrophages at 100× (a) and 400× (b) magnification. Skin biopsy at 400× magnification showing perivascular infiltration of histiocytes (c). MRI brain showing axial FLAIR image with predominant frontal atrophy in case 2 (d). Axial FLAIR (e) and T2 image (f) of case 3 showing periventricular hyperintensities along with diffuse atrophy.

Twenty-nine-year-old male had progressive gait disturbance along with cognitive decline in the form of executive dysfunction along with apathy beginning at the age of 21 years (Case 3). He developed apraxia early in the disease course with difficulty in using gadgets and simple tools followed by progressive gait disturbance with swaying while walking and unprovoked falls. He had spastic dysarthria, VSGP (prominently involving downgaze), and axial and appendicular cerebellar ataxia. The patient also had distal myoclonus, blepharospasm, and mild hepatomegaly with an NPC-SS of 90. Brain MRI showed cerebral atrophy with confluent T2/FLAIR hyperintensities in deep white matter (Figure 1e, f).

Thirt-one-year-old female had intentional tremors of hands for the past 4 years, leading to a significant change in her handwriting (Case 4). This was followed by cerebellar ataxia and dystonic posturing of the left hand that increased on walking. In the past year, she developed memory problems and depressive symptoms. The vertical saccades were slow, and pursuits were broken with downgaze VSGP. She had mild upper limb cogwheel rigidity with asymmetrical upper limb and facial dystonia. She had distal, rapid, jerky movements suggestive of cortical myoclonus in both upper limbs (Video 3). The examination also revealed pan-cerebellar dysfunction with brisk deep tendon reflexes.

A 34-year-old male presented with a 4-year history of gradual difficulty in planning, calculation, and handling finances (Case 5). One year after symptom onset, he had social disinhibition, inappropriate sexual behavior, and emotional lability. After an year of onset, he developed left lower limb dystonia that progressed to generalized dystonia involving all four limbs and the trunk. Additionally, examination revealed appendicular rigidity, slow saccades, and VSGP. His MMSE was 26/30, with frontal and parietal lobe dysfunction. Splenomegaly was found clinically and confirmed on ultrasound.

NPC is a multisystem disease with a wide range of psychiatric, neurological, and visceral manifestations. The adult-onset form of the disease is rare, and only a few case series have been reported (Table 2).

Table 2: Clinical characteristics of adult patients with NPC in different serie

VSGP- vertical supranuclear gaze palsy.

In an international disease registry, 27% patients had adolescent/adult-onset. Reference Patterson, Mengel and Wijburg1 The mean age of onset of symptoms in our series of adult/adolescent onset of NPC patients was 20.7 years (range 10–30 years), which is similar to the age of onset of neurological or psychiatric manifestations reported previously for adult patients with NPC Reference Bonnot, Gama and Mengel3,Reference Sévin, Lesca and Baumann4 . Late adult-onset of NPC has been rarely reported. Reference Kumar, Rizek, Mohammad and Jog5 A diagnostic delay of 4–17 years was found in our case series, likely due to a low index of suspicion, nonspecific phenotype, and a lack of well-defined diagnostic criteria. Table 2 compares the current series' clinical profile with that of two large adult-onset NPC series.

Among adults, movement disorders have been reported in 58–62% of patients. Reference Bonnot, Gama and Mengel3,Reference Sévin, Lesca and Baumann4 Dystonia, the most common movement disorder in NPC, is reportedly more commonly in adults than children. Reference Bonnot, Gama and Mengel3 All of our patients had one or more type of movement disorder as part of their clinical presentation probably because of their recruitment from the movement disorder clinic. There is variability in the percentage of patients who had dystonia as a clinical feature based on the type of patients enrolled. In a study that screened patients with cerebellar ataxia and cognitive decline for NPC1 mutations screening, only one patient had dystonia whereas in other cases series of adult/adolescent-onset NPC, 40% of patients had dystonia. Reference Schicks, Muller vom Hagen and Bauer6,Reference Anheim, Lagha-Boukbiza and Fleury-Lesaunier7 In contrast, dystonia was part of the clinical spectrum in all of our patients. Cerebellar ataxia has been found to be the commonest movement disorder in a previous case series but was the second most common movement disorder in our case series. Reference Anheim, Lagha-Boukbiza and Fleury-Lesaunier7 Four of our patients had cerebellar ataxia, two had tremors and one had chorea. NPC patients can have different kinds of myoclonus including rhythmic cortical myoclonus, stimulus-sensitive myoclonus, and myoclonic storm. Reference Anheim, Lagha-Boukbiza and Fleury-Lesaunier7 The patients in our series had clinical features in keeping with cortical myoclonus. Similar to other series, hyperkinetic movement disorders were dominant in our case series and only two patients had parkinsonism. Reference Anheim, Lagha-Boukbiza and Fleury-Lesaunier7

Psychiatric manifestations have been reported in 25–45% of patients with NPC, including depression, apathy, delusions, hallucinations, self-mutilation, bipolar disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. Reference Patterson, Mengel and Wijburg1,Reference Bonnot, Gama and Mengel3,Reference Sévin, Lesca and Baumann4 Three of our patients had psychiatric symptoms. Early-onset psychiatric manifestations without other neurological features can lead to a delay in diagnosis and could be challenging to manage. Additionally, if neuroleptics are used to manage the psychiatric symptoms, it could be a challenge to discern the etiology of movement disorders from drug-induced dyskinesia.

Cognitive dysfunction has been reported in 61% of 68 adult patients with NPC. Reference Sévin, Lesca and Baumann4 Similar to our series, frontal lobe dysfunction, apathy and mutism, aphasia, apraxia, and memory impairment have been reported in late-onset NPC cases, with frontal dysfunction being the most common. Reference Bonnot, Gama and Mengel3,Reference Sévin, Lesca and Baumann4

Brainstem and cerebellar dysfunction in the form of VSGP, dysarthria, dysphagia, gelastic cataplexy, deafness, and ataxia are the key features that should point toward the diagnosis of NPC. Movement disorders, VSGP, dysarthria, and ataxia are more common in late-onset NPC and has been reported in large proportion of patients in all the case series (Table 2). Reference Bonnot, Gama and Mengel3,Reference Sévin, Lesca and Baumann4 Vertical supranuclear saccade palsy with isolated vertical saccade initiation delay (Video 2) is a clinical hallmark of the adult-onset disease that may help in earlier diagnosis of this rare disorder. As the disease progresses, VSGP emerges.

Bone marrow aspirate is a relatively accessible tissue to demonstrate the lipid storage that is the hallmark of the disease. Foamy macrophages/sea blue histiocytes were seen in four out of five of our cases. However, with increasing availability of the genetic testing, this invasive test is not necessary for diagnosis. NPC suspicion index is a tool which aids in screening for patients with a high likelihood of NPC for further diagnostic evaluation. A score ≥70 should warrant NPC genetic testing. Reference Wijburg, Sedel and Pineda8

About 550 NPC1 and 29 NPC2 variants have been reported to date (The Human Gene Mutation Database, http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php). The p.Gly992Arg pathogenic variant in the NPC1 gene found in one of our cases, resulting in c.2974G>C, has been reported previously in multiple individuals with Niemann-Pick disease type C. Reference Millat, Marçais and Tomasetto9,Reference Sedel, Chabrol and Audoin10 Three of our patients showed novel homozygous missense variation in exon 3 of the NPC2 gene (chr14:74951123G>T; c.358C>A) resulting in substitution of Threonine for Proline at codon 120 (p.Pro120Thr). Different missense variation c.358C>T (rs104894458) that causes p.Pro120Ser has been reported in Iranian patients with juvenile/adult-onset disease with slow progression, similar to our cases. Reference Alavi, Nafissi, Shamshiri, Nejad and Elahi11 The novel change c.358C>A, found in three of our patients, seems to be a common variant in the Indian population with late-onset NPC and needs further exploration.

NPC is a rare neurodegenerative disease with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations. A high index of suspicion for NPC should be kept for patients presenting with movement disorders like dystonia, ataxia along with VSGP irrespective of the age of presentation.

Ethics Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects for publication.

Statement of Authorship

JP: Drafted the manuscript, Management of the patient

DD: Concept, review and editing of manuscript, Management of the patient

BA: Editing the genetics part of the manuscript

MK: Editing the genetics part of the manuscript

RR: Editing the manuscript, management of the patients

DV: Editing the manuscript, management of the patients

RKS: Editing the manuscript, management of the patients

RB: Editing the manuscript, management of the patients

NG: Editing the genetics part of the manuscript

MT: Editing the manuscript, management of the patients

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2021.222.