Introduction

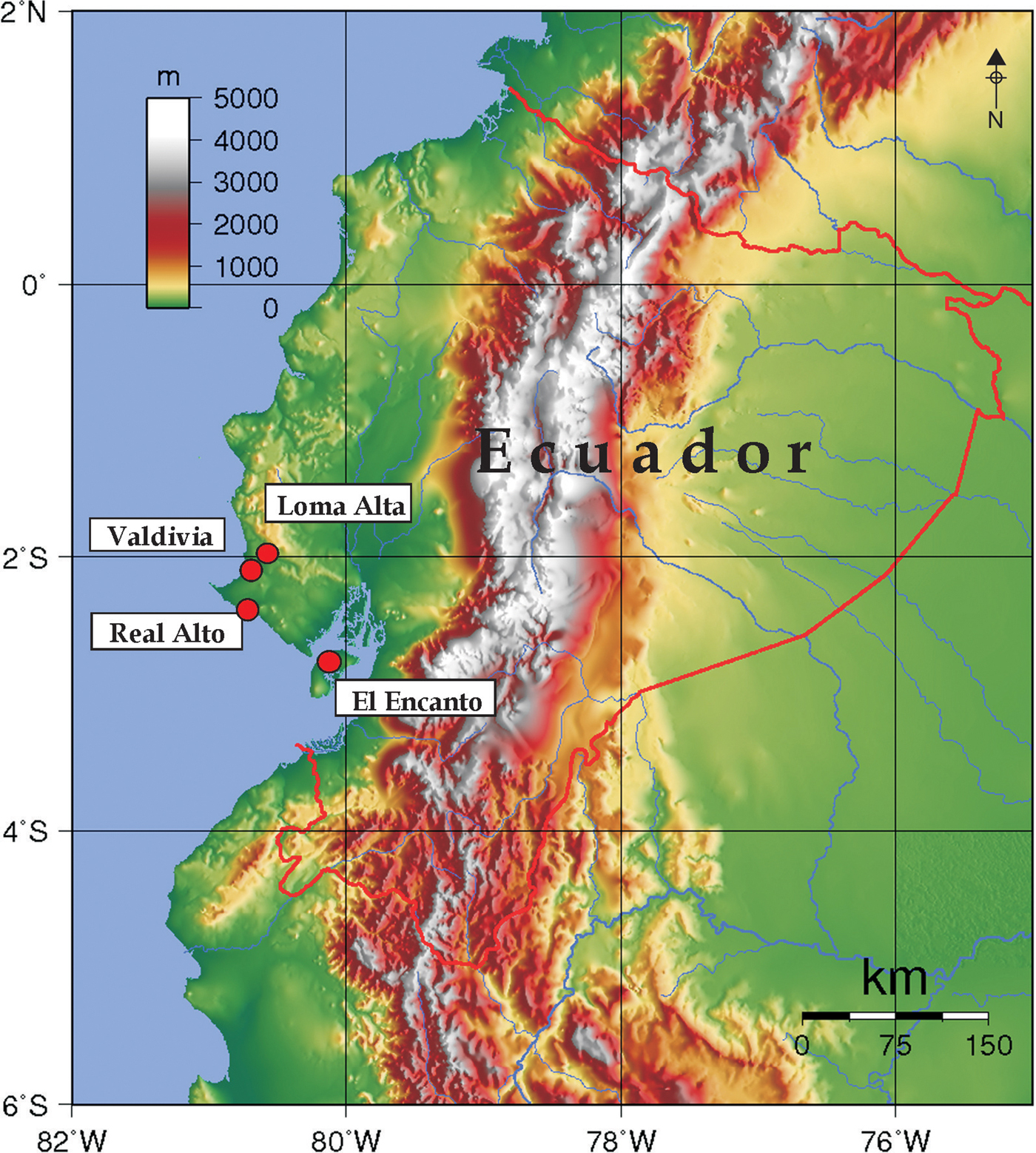

The quest for incipient pottery technology in South America originated in the late 1950s with the discovery of Early Formative complexes in lowland Colombia and coastal Ecuador (Hoopes Reference Hoopes1994) (Figure 1). In the 1960s, pottery from the Valdivia site was interpreted by Estrada and his American colleagues to indicate direct influence on Ecuador from the Jōmon culture of the Japanese Archipelago around 3050 BC (Meggers et al. Reference Meggers, Evans and Estrada1965). The oldest dates at the site, however, were associated with Valdivia 2 (2650–2350 BC), and subsequent investigations at Real Alto and Loma Alta during the 1970s and 1980s suggested a local origin based on pottery from an even earlier period (Valdivia 1: 3650–2650 BC).

Figure 1. Location of sites in Ecuador (figure by authors).

Bischof and Viteri (Reference Bischof and Viteri1972) re-analysed materials from a Valdivia profile and suggested that Valdivia 2 was preceded by a more ancient complex represented by 27 sherds: the San Pedro complex. Lathrap with colleagues (Lathrap et al. Reference Lathrap, Collier and Chandra1980: 27) wrote that the earliest Formative period is represented by two pottery traditions: San Pedro and a “yet undiscovered complex ancestral to the earliest Valdivia”, or Valdivia 1. Damp and Vargas (Reference Damp, Vargas, Barnett and Hoopes1995) reported a small number of San Pedro sherds (trench C at Real Alto) at depths between 0.4–0.6m, stratigraphically below the living floor of Valdivia 2. At other sites (Valdivia, El Encanto), these were also located below those containing Valdivia 2 deposits, so he postulated a chronological position between Valdivia 1 and 2 (Damp & Vargas Reference Damp, Vargas, Barnett and Hoopes1995).

New excavations at Real Alto

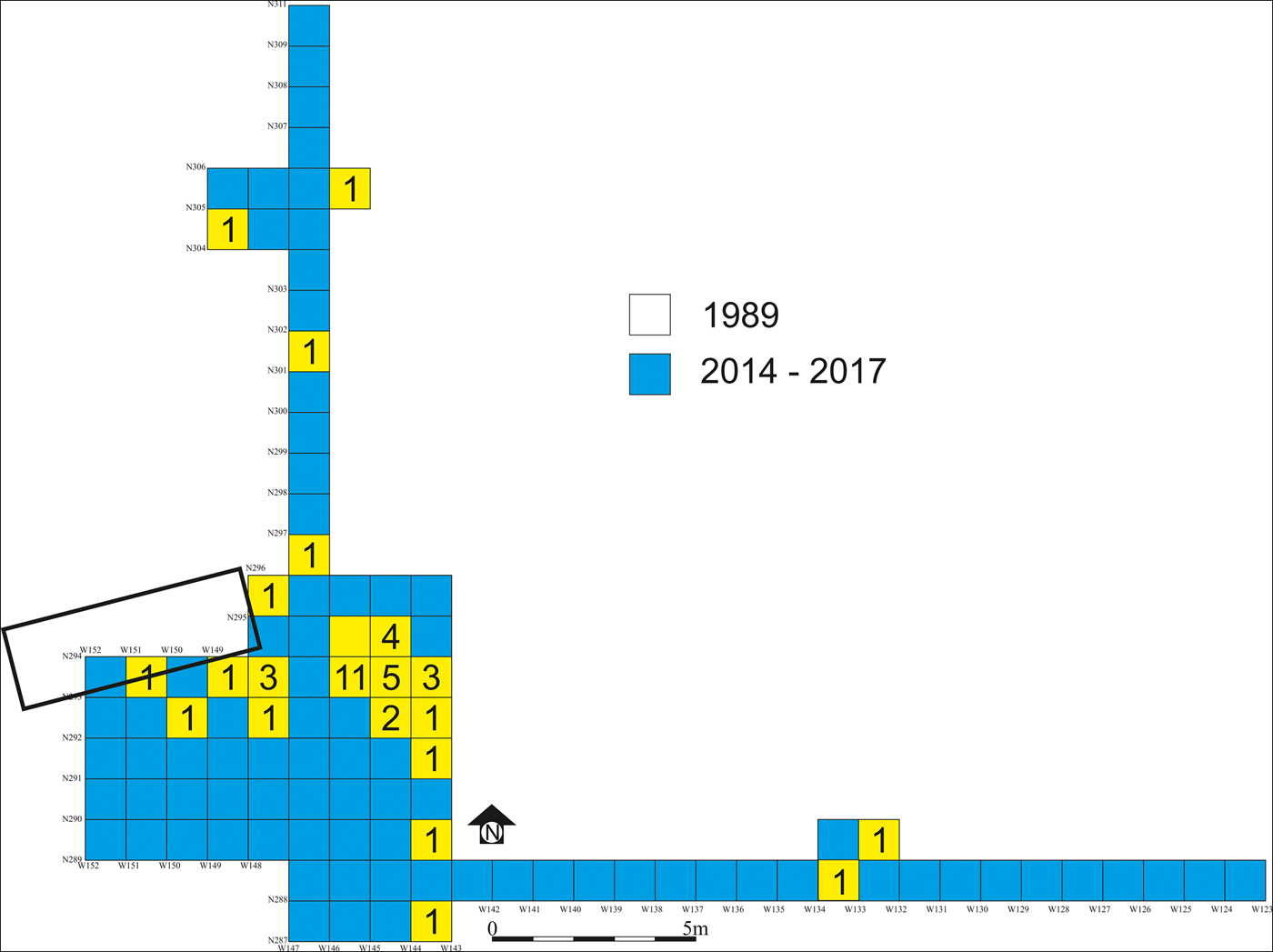

Since 2014, the transition from pre-ceramic to early ceramic cultures on the Ecuadorian coast has been the focus of a Russian-Japanese-Ecuadorian project. New excavations in the far north-east portion of Real Alto (with the excavation area, including two trenches, totalling 102m2) revealed strata corresponding to Valdivia 1 and 2 as well as earlier non-ceramic periods (Tabarev et al. Reference Tabarev, Kanomata, Marcos, Popov and Lazin2016).

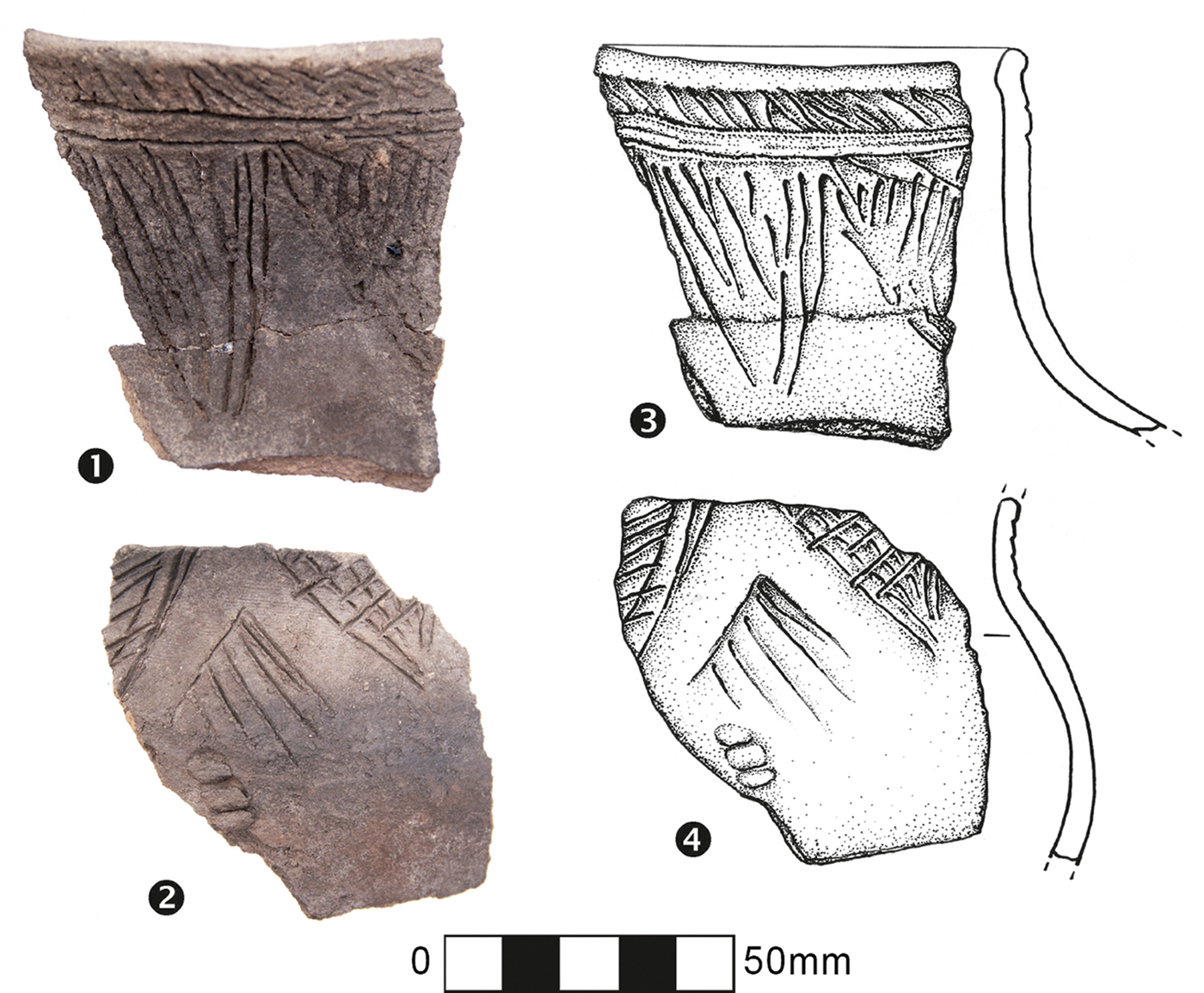

In 2015, San Pedro sherds were recovered at the interface of Valdivia 1 and non-ceramic horizons (Figure 2). This was followed in 2017 by the discovery of a larger concentration of San Pedro sherds at the site (Figure 3), while a review of materials from a 1989 test pit at Real Alto in collections at ESPOL revealed additional sherds (Figure 4). In 2018, almost half of a vessel was found during the cleaning of trench 2 (Figure 5). This work produced a total sample of more than 40 sherds from several vessels of the San Pedro complex with additional contextual data. All were stratigraphically located 0.75–1m below the surface, 85 per cent in a zone between 0.8–0.9m (Figure 6). Sherds are either black or black-and-brown, from bowls and globular, necked jars, 4–5mm thick. They were made using grog and stone temper, including some large (approximately 3mm) particles visible on the surface. The pottery is handmade and constructed from clay coils that were subsequently smoothed without burnishing on either the exterior or the interior. It appears to have been fired at a low temperature (approximately 800–1000°C), and the appearance is typical of firing in reducing conditions (limiting the amount of oxygen during the firing process). The rough, geometric decorations were made with shallow, linear incisions that had irregular margins as well as finger-gouging and rows of round punctation. Charcoal residues suggest that some vessels were used for cooking.

Figure 2. San Pedro sherds, 2015: 1–2) photographs; 3–4) drawings (figure by authors).

Figure 3. San Pedro sherds found in 2017 (photograph by authors).

Figure 4. San Pedro sherds from the ESPOL collections (photograph by authors).

Figure 5. San Pedro sherds found in 2018 (photograph by authors).

Figure 6. Real Alto: distribution and number of San Pedro sherds (yellow boxes) within excavation area (trenches 1–2) (figure by authors).

The characteristics of San Pedro pottery differ considerably from the typical red-slipped and burnished Valdivia vessels, which are often decorated with more deliberate, smooth-sided incisions. For the first time, AMS dates have been obtained directly from the carbon residue samples on two different vessels of San Pedro pottery. These are very close together: 4640±20 BP (IAAA-171318) and 4460±30 BP (IAAA-181069); and they are contemporaneous with the end of Valdivia 1. While not the earliest dates from Real Alto, they provide a chronology for San Pedro pottery with much higher confidence than previous studies.

Conclusion

These new data on San Pedro pottery from Real Alto demonstrate its stratigraphical, typological and chronological identity as one of the earliest ceramic forms in the Americas, and they confirm the existence of Early Formative cultural variability in Ecuador.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (16K03149, 16KK0020).