In pre-modern societies, long-distance trade constituted a key motor for economic growth. The expansion of trade in the British Atlantic facilitated social mobility and the emergence of the middling sorts as an economic and political force in England. Some prominent scholars have argued that it laid the foundations for the Industrial Revolution, making it the root of present-day global inequality.Footnote 1 The factors determining trade expansion, however, remain unclear. Economic historians researching trade have been strongly influenced by the New Institutional Economists (NIE).Footnote 2 These argue that within Europe, the emergence of strong, centralised states who enforced property rights enabled trade. European states were however unable to extend their control to the American colonies. The growth of trade in the Atlantic despite weak state structures poses a puzzle yet to be solved.

This article offers a solution to this puzzle. Based on the extensive records of colonial Philadelphia's Quaker Monthly Meeting, it shows that in the face of weak state institutions, formal religious institutions evolved to enforce property rights. Its argument is threefold. First, the Meeting established its own legal forum, where it solved commercial disputes through arbitration. Second, it did this in order to compensate for the unreliable public courts. Third, it ensured that litigants honoured its decisions by means of a formally reinforced reputation mechanism. The importance of reputation mechanisms in early modern trade is well established. The Quaker Monthly Meeting is distinct as it found a way to employ reputation mechanisms formally, thereby increasing their impact. It gathered, verified and published information about conflict parties and its own verdicts through the formal institutions of the Society of Friends. Thereby, it made sure that the information it had was reliable. Through its formal institutions, the Society was able to spread this information more widely and with greater credibility, thereby achieving greater impact than reputation mechanisms based on informal networks. This worked while Philadelphia's population remained small and relatively homogenous. When immigration increased and the city's society grew more diverse, the reinforced reputation mechanism lost its power and merchants stopped using Philadelphia Monthly Meeting for dispute resolution.

The article further explains that the reason scholars have paid little attention to the role of formal religious institutions in trade lies in the lack of communication between historical disciplines. Economic historians researching trade have ignored research by legal historians. These have established that the early modern world was legally pluralistic, bodies other than the state providing and enforcing law the norm. Combining these two disciplines’ findings reveals an explanation for the expansion of trade in the early modern Atlantic. The findings, moreover, hold implications for the roots of pre-modern trade expansion globally.

The article is divided into nine sections. Section 1 reviews the scholarship on pre-modern long-distance trade and sets out the problem of explaining Atlantic trade expansion. Section 2 discusses the scholarship on pre-modern legal institutions and governance. It shows that by relying too strongly on the New Institutional Economics, trade historians have missed legal historians’ findings on the legal pluralism of pre-modern societies. Section 3 sets out the current state of knowledge on Quaker dispute resolution. Section 4 outlines the legal, political and economic situation of early colonial Pennsylvania. Section 5 provides an empirical study of the number and types of disputes Philadelphia Monthly Meeting solved. Section 6 shows that a high percentage of conflict parties in the Meeting were merchants. Section 7 conducts a comparison between Philadelphia and London Monthly Meetings and reveals that dispute resolution was not an inherent part of Quaker discipline, but particular to the colonial context. Section 8 outlines how Philadelphia Monthly Meeting enforced its verdicts, using a special mechanism based on both formal structures and reputation. Section 9 sums up the findings and discusses their implications for our understanding of pre-modern trade expansion in general, and trade in the Atlantic in particular.

1. The fundamental problem of exchange

The key element inhibiting trade expansion is risk. Long-distance trade is marked by a time lag between delivery of goods and payment. Merchants in locations that are far apart agree to exchange payment and goods. They accept the risk that the other party will not deliver as promised. Such a breach of contract may cause financial ruin. Thus, this risk needs to be mitigated for trade to occur. The smaller the risk, the more individuals will be willing to enter the market, the more trade and exchange will take place, and the more economic growth occurs. In consequence, prosperity may increase and living standards improve. A growing body of opinion sees institutions as the solution to this problem. Depending on the quality of institutions for contract enforcement, trade will grow – or not – in a given time and place. This implies that trade increases reflect institutional improvement.

According to the NIE, in early modern Europe the state emerged as the main guarantor of property rights.Footnote 3 Beginning in the late Middle Ages, European countries moved from a situation in which private order institutions dominated contract enforcement towards one in which the state played an ever greater role. Public courts, relying on the state's monopoly of force to carry out their verdicts, came to replace earlier, private institutions. The English state proved particularly successful in monopolising contract enforcement. Over the course of the early modern period, it developed an increasingly centralised judicial system, which dealt out justice throughout the state's territory.Footnote 4 According to Douglass North and Robert Thomas, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 was a watershed in this development. It enabled the central government to consolidate control and complete the centralisation of the judicial system. This was important, as North and Thomas argue, because it allowed public courts to enforce contracts throughout the state's territory.Footnote 5 Similar developments took place, albeit to a less complete degree, throughout Europe. This meant that merchants in Europe could resort to courts when business associates broke their promises to pay debts or deliver wares. The courts heard the dispute, found one party guilty and ordered them to pay. The state then enforced its courts’ verdicts. Thereby it facilitated trade expansion and sustained economic growth.Footnote 6

In areas where courts were either unavailable or inefficient, merchants had to rely on private or community-based institutions to enforce contracts. Avner Greif famously theorised that in the medieval Mediterranean, the Maghrebi merchants used multilateral reputation mechanisms to enforce contracts. Any merchant who broke a promise was ostracised and lost the prospect of future trade with any member of the community. However, membership in pre-modern merchant communities was based on faith, kinship or other pre-existing, non-economic, criteria. This limited the number of those who could use the reputation mechanism, and thereby the number of people who would participate in the market. These private order institutions were, therefore, less capable of supporting trade than public courts, setting limits to market expansion and economic growth.

While Greif maintained that merchants accessed either public or private order institutions, and that these emerged sequentially, with public order institutions replacing private order ones, researchers including Jessica Goldberg, Regina Grafe and Oscar Gelderblom have since shown that pre-modern merchants used both state and private order institutions in tandem, making use of any tool available to reduce risk.Footnote 7 In the colonial trades, these included multilateral reputation mechanisms based on kinship, local origin and faith.Footnote 8 Merchants used courts, but only as a last resort. As Philadelphia merchant Isaac Norris informed a correspondent about his attempts to secure a debt, ‘I have been very pressing with Jos. Jones, and do all in my power, but don't love the law’.Footnote 9 Early modern merchants across the Western hemisphere shared in this sentiment.Footnote 10 Courts were expensive and slow; they could harm one's reputation and were thus best avoided.

Legal historians agree that whenever possible, traders resorted to arbitration instead.Footnote 11 This was particularly true for American merchants, who were faced with unreliable public courts. Their preference for arbitration continued until the mid-eighteenth century, when courts improved and litigation became prevalent.Footnote 12 For arbitration to be able to solve disputes and enforce contracts, arbitration awards need to be enforced. Yet it is unclear how American colonists accomplished this. Bonds are one contender.Footnote 13 A bond obliged parties to a contract to pay a fine if they did not fulfil their side of the agreement. However, enforcing bonds required going to court, which limited their use. Given these institutional constraints, how do we explain the sustained expansion of trade that took place in the Atlantic during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century?

Scholarship on Atlantic trade has overlooked an important piece of the institutional puzzle: the state was not the only provider of ‘law’ in the colonies. In the absence of a strong state, multiple alternatives can offer institutional solutions. These may include private corporations, such as the chartered trading companies, or religious bodies like the Anglican church. In Pennsylvania, religion was the most important of these. Religion's role as the basis for informal trading networks in the Atlantic is long established. This paper argues that religion did more than that. In Pennsylvania, the Society of Friends stepped in to fill the institutional vacuum left by weak state institutions: It established legal forums. These were formal institutions in that they followed standardised procedures based on written rules. As part of the institutional landscape of colonial Pennsylvania, they enforced contracts and thereby facilitated trade expansion.

2. Important lessons from Legal History have been overlooked

Why has the possibility of formal religious institutions enforcing contracts in the colonies been neglected? Studies on the institutional foundations of long-distance trade have been influenced strongly by the NIE view of the state. This is based on the concept of ‘legal centralism’. ‘Legal centralism’ assumes that ‘law’ only exists within and through the power of the nation state and that the nation state is in control of everything happening in its territory.Footnote 14 At the time of North's first writing on the state's role for protecting property rights in 1973, legal centralism was the generally accepted understanding of how law works. However, legal scholarship has since moved on from this view. Over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, legal historians replaced the idea of ‘legal centralism’ with that of ‘legal pluralism’.Footnote 15 There are two models of legal pluralism: ‘Weak’ legal pluralism posits that there are several legal orders in one territory, which ultimately derive their legitimacy from the state. ‘Strong’ legal pluralism frees law from its ties to the nation state. Instead, it posits that legal orders are connected to ‘semi-autonomous social fields’. A semi-autonomous social field is a ‘social group which engages in reglementary activities’.Footnote 16 It is not defined by its boundaries, but by ‘the fact that it can generate rules and coerce or induce compliance to them’.Footnote 17 At the same time, it is part of, and influenced by, a larger society.Footnote 18 Social fields overlap. Ergo, several legal orders will operate within the same social and economic space.Footnote 19 This means that within a state's territory, forces other than the state will provide and enforce law. The more socially diverse a society – its members organised along ethnic, socio-economic, religious and occupational lines – the more pluralistic the legal order in that society will be.Footnote 20

Contrary to North et al.'s theory, in early modern Europe, the state did not enjoy a monopoly of force. While it was making efforts towards greater judicial control, progress remained slow. The institutions European states created to address commercial disputes were hybrid, that is, they combined state and private elements. English bankruptcy commissions consisted of merchants who, while appointed by the Lord Chancellor, investigated commercial failures and determined debtors’ obligations and creditors' rights independently.Footnote 21 English colonies in North Africa and the Caribbean setup merchant courts, where instead of judges with legal training, merchants themselves decided commercial disputes.Footnote 22 At the King's Bench in London, Lord Mansfield relied on merchant juries in order to comprehend and decide commercial cases.Footnote 23 Sixteenth-century France created courts staffed by merchants rather than professional judges, who used their expertise to solve commercial disputes. Courts of this nature exist in France to this day, so legal centralism is still not a reality.Footnote 24

England remained legally pluralistic throughout the early modern period. Philip Loft recently showed that even after 1688, local corporations and power holders heavily curtailed parliament's influence.Footnote 25 The ‘state’ constituted one corporation among many, all of which governed by sharing power and cooperating with each other to various degrees.Footnote 26 Royal, local, ecclesiastical, and seigniorial jurisdictions, provincial and local estates, feudal lords, guilds, urban corporations and trading companies all provided and enforced law. Many of these legal institutions did not derive their legitimacy from the crown.Footnote 27 In Philip Stern's words, the early modern European ‘state’ was really a ‘composite of agents, networks, and “grids of power” that operated within, aside, and sometimes in conflict with the sovereign Crown’. Correspondingly, Larry Epstein argued that the NIE ‘project backwards in time a form of centralised sovereignty and jurisdictional integration that was first achieved ( … ) during the nineteenth century; they therefore fundamentally misrepresent the character of pre-modern states’.Footnote 28 These were unable ‘to enforce ( … ) a unified legal regime’.Footnote 29

The acquisition of overseas territories further increased legal plurality. In the colonies, new situations and conflicts arose which European law lacked the instruments to resolve.Footnote 30 Lauren Benton has shown how European empires responded to this challenge by adopting and incorporating local legal orders.Footnote 31 This understanding of the plurality of law has not yet been applied in research on the institutional foundations of long-distance trade, despite the recognised importance of semi-autonomous structures, such as the English and Dutch East India Companies in this context. As Philip Stern and Adam Clulow have shown, these corporations, crucial to the expansion of long-distance trade, enjoyed sovereignty and jurisdiction over their ‘subjects’, making and enforcing law that governed trade.Footnote 32

3. Quaker dispute resolution

One such non-state legal institution supported trade expansion in the Atlantic: the Philadelphia Quaker Monthly Meeting (PMM). Founded in 1682, Philadelphia suffered from a fragile institutional environment. The political situation was instable and the legal structure malfunctioning. These factors conspired to make Philadelphia an unlikely candidate for commercial success. Yet, the city's commerce thrived. How was this possible? This paper argues that Philadelphia Monthly Meeting played an important role in this development.

The Quaker Monthly Meeting was a religious private order institution. In colonial Pennsylvania, there were some overlaps between Quaker meetings and the state – some of PMM's officers also acted as judges or magistrates. Formally, however, the two were distinct, and the meeting was independent of the state. The Society of Friends’ arbitration procedure was based on scripture and followed the same pattern commonly used by English guilds to solve disputes between members.Footnote 33 Arbitration in a Quaker Monthly Meeting was open to Friends only. Friends were first to try and solve their differences privately. If unable to reach an agreement, the aggrieved party was to recruit some ‘judicious and discreet Friends’ to negotiate with the opponent. If their efforts failed, too, the parties were to ‘choose referees, or arbitrators’, and promise to honour their verdict. Only if an opponent refused to take this step, should Friends approach a monthly meeting for help. At the monthly meeting, the parties each chose several arbitrators who together would make inquiries, uncover evidence and discuss the conflict. The monthly meeting would ‘add one or more friends to them ( … ) for determining the said difference by a majority’.Footnote 34 The arbitrators were to determine the case swiftly and report to the next monthly meeting. Appeals could be directed to a quarterly meeting and eventually a yearly meeting.Footnote 35

We know that Friends arbitrated disputes in their meetings. Morton Horwitz argued that a Quaker preference for arbitration led to an unusually frequent use of that form of dispute resolution in Pennsylvania.Footnote 36 Carli Conklin's study of arbitration in colonial Quaker records has established that Friends in the Jerseys also used arbitration, as well as the rules by which this procedure took place.Footnote 37 Peter Philips argued that arbitration in Quaker meetings was common in the seventeenth century and gradually declined from the nineteenth century onwards. His study is based on several editions of the Society of Friends’ Discipline, using a few examples of disputes arbitrated by various American Quaker meetings for illustration. The Discipline, however, is not evidence of actual Quaker practice. It sets out how Yearly Meetings would have liked Friends to behave, while containing no information on what actually took place at the monthly meeting level.Footnote 38 None of these studies provide evidence of the frequency of arbitration in Quaker meetings, how it developed over time, who was involved and what types of conflicts were arbitrated. A quantitative study of arbitration in rural Pennsylvania Quaker meetings by William Offutt conflates dispute resolution with the meetings’ regular disciplinary procedures. In the latter, rather than responding to a member's complaint against another, monthly meetings became active on their own behalf to deal with members who broke the Quaker discipline, and whose behaviour threatened to cause the Society reputational harm.Footnote 39 This is distinct from dispute resolution, in which individual Friends approached the meeting with cases of disagreements with each other. As a consequence, the image that emerges from Offutt's study is distorted, overestimating the use of dispute resolution. To sum up: We know that Quaker dispute arbitration took place in Pennsylvania, and we know the formal rules the Society laid out for the procedure. So far, we do not know how common the procedure was, who used it, and what types of disputes they brought to the meetings.

4. The Quaker colony and its courts

The Quakers are a dissenting group that emerged during the English Civil Wars in the 1640s. Their core belief was the immediate relationship between the individual and God, without the need for priests to serve as intermediaries.Footnote 40 They emphasised the importance of personal religious experience over the knowledge of scripture. The participation of those ‘convinced’ was central. At meetings, Friends might sit completely silent for hours, each listening for the voice of God within.Footnote 41 The early Quakers missionized very successfully, and by 1700, there were about 50,000 Quakers worshiping in meetings all over the British Empire.Footnote 42 A formal, hierarchically structured organisation connected their meetings. At its lowest tier stood local meetings for worship, where Friends gathered several times a week. At the next higher level stood the monthly meetings. They consisted of respected community members, often merchants or other, wealthier Friends. The monthly meetings were responsible for the administration of the communities in their areas. They organised poor relief, registered births, solemnised marriages, maintained Friends’ buildings and burial grounds. In this, they shadowed the Anglican parish. Quaker Monthly Meetings, furthermore, sanctioned Friends whose behaviour might cause the community's reputation to suffer, such as public drunkenness. Monthly meetings also kept up a regular correspondence with other Quaker meetings.Footnote 43 They sent emissaries to quarterly meetings, which in turn dispatched representatives to yearly meetings. Yearly meetings were the highest body within the Quaker organisation, possessing the greatest authority. The most important yearly meetings were located in London and Philadelphia. They formulated Quaker policies regarding all issues that concerned Friends or the public at large, from how to raise one's children to participation in privateering. They issued annual letters, called epistles, which form the basis of the Quaker discipline. They also decided internal conflicts. Their decisions were binding for all lower-tier meetings.

Until 1660, Quakers tried to bring about a radical reform of society. Emphasising equality before God, Friends rejected the authority of the Anglican Church and to a certain degree that of the state. The government responded to their dissent from social and political order with persecution. It banned Quaker meetings and expropriated Friends’ possessions. Thousands were incarcerated, hundreds died in prison.Footnote 44 Only with the Toleration Act of 1689 did persecution decrease and Friends gain some security.Footnote 45 In response to persecution, in 1681, William Penn obtained a charter from Charles II to found Pennsylvania as a place where Friends could live safely in accordance with their beliefs.

Settlement of the colony began in 1682. Historians agree that it was an immediate success.Footnote 46 Within three years of the first ships’ arrival, Philadelphia ‘was firmly established in the Barbados provisioning trade and had cut deep inroads into New York's control of the middle-Atlantic fur and tobacco markets’.Footnote 47 Gary Nash concluded that ‘There are few parallels in colonial history to the economic success of Pennsylvania in the first two decades’.Footnote 48 Philadelphia exported tobacco, skins, furs, lumber and flour to the West Indies. In return, its merchants received bills of exchange. These were used to purchase English manufactured goods via the New England colonies. This pattern lasted almost 40 years. Around 1720, a major change occurred: More wheat and flour were sold to Southern Europe and Ireland, and the coastal trade with the other colonies grew, too. In the following years, Philadelphia's external trade almost tripled.Footnote 49

Demographic developments mirrored these economic ones. In 1690, Philadelphia counted roughly 2,000 inhabitants, including 1,100 Quakers.Footnote 50 The city's population stagnated until 1718. Then, immigration increased. In 1720, just below 5,000 inhabitants lived in Philadelphia. By 1775, their number had grown to 32,000.Footnote 51 The new arrivals were pre-dominantly non-Quaker, many stemmed from continental Europe.Footnote 52 It is unclear when Friends became outnumbered by others. PMM's 1760 census lists 2,250 Quaker women, men and children.Footnote 53

Until about 1720, the colony suffered from political and legal instability.Footnote 54 The frame of government changed repeatedly.Footnote 55 The colonial assembly frequently passed laws, only to have them repealed by the crown. Offutt found that Pennsylvania suffered ‘the highest percentage of disallowed colonial legislation’.Footnote 56 For instance, in 1706, the Privy Council revoked 53 of 105 laws submitted by the assembly.Footnote 57 In between sending laws for approval to England and hearing back about their acceptance, rumours and uncertainty ruled. This led to general confusion over which laws were in place, as well as colonial courts’ jurisdiction.Footnote 58

Pennsylvania had four types of courts: The county courts sat four times a year, alternatively as courts of quarter sessions and common pleas. The quarter sessions heard non-capital criminal cases, while courts of common pleas handled civil disputes. In addition, there was an orphan court, which administered decedents’ estates and appointed guardians for their children. The lines between these courts were permeable, as the same judges presided in all four, deciding cases in common pleas, sessions, equity and orphan courts.Footnote 59 Finally, a ‘Provincial Court’, which travelled from county to county in circuit, heard the most serious criminal cases as well as appeals from civil and equity cases.

Of special importance to our study is equity jurisdiction. This was controversial, and nowhere more so than in the Quaker colony.Footnote 60 According to Stanley Katz, ‘Controversies over the nature of jurisdiction of equity courts was a distinguishing feature of early Pennsylvania political life’.Footnote 61 Proponents of equity courts argued that these were essential to economic development, as they remedied short-comings of common law which made it difficult to obtain justice in commercial cases. Proceedings in common law were bound by a stiff framework. Pleadings had to fall within established writs – or formulars – to allow for litigation. This considerably narrowed the types of grievances plaintiffs were able to bring to court. Common law pleadings, furthermore, had to be framed in a way that ‘narrowed the dispute to a single question of law raised against a single defendant’, in order to make them easier for juries to understand and decide. Moreover, common law did not permit the parties themselves to appear as witnesses, thereby disqualifying important evidence.Footnote 62 In equity courts, in contrast, plaintiffs were able to file cases against multiple parties, and others involved in the suit were able to add their own related claims. Equity courts relied on testimonies in writing, including that of the dispute parties, and generally included a broader range of evidence. This, as Amalia Kessler put it, increased ‘the probability that the suit would be decided in accordance with the actual facts’.Footnote 63

Some colonists worried because equity courts acted without juries, while at the same time being headed by the governor. They feared such courts would give too much power to proprietors, while disadvantaging the colonists. For instance, it might force them to pay quitrents.Footnote 64 These concerns existed across the American colonies. Different provinces found different solutions for the dilemma. New York, Maryland and South Carolina did introduce chancery courts, which were active for long periods of time.Footnote 65 Most of the New England colonies incorporated equity law and procedure into common law legislation and courts. In Massachusetts, home to the highly successful port of Boston, county courts were empowered to ‘act as courts of equity, and they retained this authorization throughout the colonial period’.Footnote 66 Pennsylvania experimented in this direction. Equity powers of common law courts were introduced or confirmed repeatedly between 1684 and 1720. However, the Queen repealed them each time. This meant that in the period between the assembly passing the legislation granting equity powers to the county courts, and news of the repeal reaching Pennsylvania, the county courts did hold these powers. They lost them the moment the repeal became known. Courts with equity powers were active in Pennsylvania briefly after 1684, again from 1690 to 1693, from 1701 to 1705, from 1710 to 1713 and 1715 to 1719.Footnote 67 This back and forth led to constant confusion over whether the courts held equity powers or not.Footnote 68 Importantly, it also caused insecurity as to whether verdicts issued by equity courts in these periods would hold and be enforced once the courts lost their equity powers again. Only in 1720 would the colony finally establish a durable equity court, which operated until 1736.Footnote 69 After the final abandonment of this court, common law courts slowly began to adopt individual equity procedures.Footnote 70

The insecurity regarding Pennsylvania's courts was further aggravated by the ‘oath controversy’ from the 1690s to about 1720.Footnote 71 The English legal system required the swearing of oaths throughout. As part of their beliefs, Friends refused to swear. In Pennsylvania, they therefore replaced oaths with affirmations. However, Pennsylvania colonists from the outset included other protestants as well. Soon, a power struggle between Friends and non-Quaker settlers emerged, centring around the use of oaths. Anglicans argued that the lack of oaths made the justice system unfit to deal with crime, lobbying for a replacement of affirmations by oaths locally and with the government in England. Losing the option of affirming would have put Quakers at a serious disadvantage in the legal system, making it impossible for them to litigate, and excluding them from acting as judges or jurors. Moreover, it raised the question whether courts’ decisions based on the use of affirmations would continue to be binding, if these became outlawed. Churchmen brought the legal process to a halt repeatedly.Footnote 72 Between 1705 and 1710, Pennsylvania's courts functioned merely based on ordinances issued by the governors. During brief periods in 1708 and 1709, they did not sit at all.Footnote 73

Political instability further eroded trust in the courts. William Penn was twice arrested after the Glorious Revolution under charges of treason, due to his close relationship with former King James II. Between 1692 and 1694, the colony came under crown control, as it failed to take measures to defend itself against the French in the War of the League of Augsburg.Footnote 74 In 1708, Penn again was imprisoned, this time for debts. Close to bankruptcy, he prepared to sell the colony to the crown. These plans hung over Pennsylvania until his death in 1718. Penn's heirs held on to the colony and appointed governors to represent their interests vis-à-vis the Pennsylvania Assembly. The legal and political situation improved dramatically from about 1722 onwards.Footnote 75 Political unrest calmed down, laws remained in place and courts sat regularly.

Given the constraints described above, how did Philadelphia Quaker merchants solve commercial disputes and enforce contracts? The inhabitants of early modern European states and empires, including merchants, compared the services and possible outcomes they could expect from dispute resolution in different legal forums, choosing the one they thought would provide for them most desirable outcome.Footnote 76 The seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century records of Delaware Valley courts outside Philadelphia show that in spite of their unreliability, Friends at times did apply to the courts for help.Footnote 77 Moreover, their letters show that they often used informal arbitration, which was common practice in both the colonies and England.Footnote 78 In addition, as the following sections of this paper will show, Friends obtained help from the Quaker Monthly Meeting to solve disputes.

5. The Quaker meeting offers an alternative to public courts

Philadelphia Yearly Meeting's 1719 Book of Discipline first defined the types of conflicts that might be brought to monthly meetings’ attention. These included ‘differences (that) happen or arise between any Friends’ in ‘their interests, claims or properties in worldly affairs’.Footnote 79 It specified debts, bonds and ‘differences in accounts’.Footnote 80 This tells us first, that the Yearly Meeting intended the arbitration process not for spiritual or religious matters, but for conflicts of a secular nature. Specifically, it had in mind differences that arose during the conduct of business – conflicts likely to involve contracts. To what extent did PMM employ this procedure? What types of conflicts did it focus on in practice? Its minutes provide answers to these questions. They survive for the entire colonial period. In 1772, PMM split in three to accommodate the growing size of the city and community. For the sake of simplicity, this study uses only the records of the original monthly meeting and ends in 1772 (Table 1).

Table 1. Conflicts arbitrated by Philadelphia Monthly Meeting

Source: Haverford Special Collections, Philadelphia Monthly Meeting Minutes.

The minutes specify the causes of conflicts for 161 cases (56.1 per cent). The remainder concerns undefined ‘differences’ or ‘complaints’. Which causes were specified appears determined by chance. The known causes were divided into categories according to issues which appeared most frequently. The largest category is ‘debt’, constituting 57.5 per cent of causes. In 1744, for example, George James complained that Samuel Redman was ‘indebted to him and delays payment’.Footnote 81 PMM appointed two Friends to ‘use their endeavours to get the matter accommodated’.Footnote 82 The following month, these reported that Redman ‘promiseth to pay the money in a few days’.Footnote 83 In response, PMM directed the two Friends to follow up on the case, to ensure he kept his promise. Again, the following month, they reported to the meeting that the procedure continued, and the next, the minutes noted that it was ‘ended’.Footnote 84

The next largest group is ‘estates’, with 21.9 per cent. This includes cases in which creditors complained against the executers of deceased persons’ estates. The vast majority of these concern the settlement of debts owed by, or to, the deceased. Therefore, both ‘debts’ and ‘estates’ constitute conflicts over the payment of debts. Together, conflicts over financial obligations make up at least 79.4 per cent of cases PMM arbitrated.

A closer look at the debt cases reveals that they often concerned commerce, some explicitly long-distance trade. They include conflicts over bills of exchange, differences in accounts and money lent on bond.Footnote 85 The minutes often do not specify whether the conflict was between Friends residing in Philadelphia, or elsewhere. While PMM arbitrated his complaint, Francis Richardson was actually living in New York. This is not obvious from the minutes, however, and is only revealed by his correspondence.Footnote 86 Other Friends in PMM may have acted as agents for their overseas correspondents, without this being specified in the minutes. Fifteen cases (16.3 per cent) can with certainty be identified as involving at least one party living in a different colony or in England.Footnote 87 These Friends were represented at PMM by their agents, or their home meetings approached PMM by letter.

For instance, in 1687, Daniel Wharley, Quaker and hatter of London needed help with a bill of exchange he received from Philadelphia Quaker merchant Griffith Jones. Instead of taking the case to court, Wharley asked his correspondent, Samuel Carpenter, merchant of Philadelphia, for support. Carpenter approached Jones but could not convince him to compensate Wharley for the protested bill. As a next step, Carpenter turned to PMM. He reported Jones ‘for not satisfying this Bill of Exchange to him in the behalf of Daniel Wharley with charge of protest and interests since it became due’. He requested PMM exert pressure on Jones. PMM directed that:

Griffith Jones shall pay unto Samuel Carpenter on the behalf of Daniel Whaley the money due upon the aforesaid bill of exchange protested, with the lawful damage and protest, and also the full interest of six p cent since the first day the bill arrived in Pennsylvania after it came back protested from England, and to pay the same in silver money or to content of the said Carpenter in three months after this day without fail.

The ‘lawful damage and protest’, and the interest rate of six per cent were standard procedure in Pennsylvania at the time. PMM enforced commercial contracts.

6. Merchants embrace the new institution

If PMM's contract enforcement supported trade expansion, we would expect a large number of merchants among those submitting complaints or being ‘sued’. Two sources on Philadelphia merchants exist: First, Gary Nash compiled a list of Philadelphia merchants active in the city between 1682 and 1740. This is based on a wide range of colonial records and probably captures most merchants active in Philadelphia during this time. It comprises 245 merchants, including 131 Quakers.Footnote 88 Of these 131 Quaker merchants, 56 (42.7 per cent) appeared in PMM arbitration cases up to 1740. They acted either as defendants, plaintiffs, attorneys or were the deceased, whose estates their survivors negotiated.

Second, a PMM ledger containing copies of 482 marriage certificates for the period 1672–1759 survives.Footnote 89 The certificates frequently include husbands’ occupations, thus allowing the identification of arbitration parties’ occupations. Comparing the names appearing in the arbitration cases to these two sources allowed the identification of 19.6 per cent as merchants. The disproportionate importance of merchants among the conflict parties becomes even clearer when calculated for a single year. In 1690, roughly 330 adult male Friends lived in Philadelphia.Footnote 90 Of these, ten (3 per cent) were merchants.Footnote 91 That year, PMM arbitrated nine disputes, involving 21 individuals. Of these, seven, or 33.3 per cent, were merchants.

Clearly, a significant number of Philadelphia Quaker merchants used PMM to solve disputes, and a disproportionate number of arbitration parties were active in trade. Merchants found PMM useful for enforcing contracts, suggesting that it supported trade expansion.

7. Why did the society of friends resolve disputes?

But why did PMM become involved in its members’ commercial conflicts? The reason was the colony's weak institutional environment. This becomes apparent when comparing the conflicts which PMM negotiated to those brought before the courts. Only one Philadelphia court ledger survives for the early colonial period. It contains Philadelphia county court's cases for the year 1695/1696. That year, the court sat four times each as a court of common pleas and quarter sessions. The court of common pleas that year held equity powers.

The 1695/1696 Philadelphia court ledger was used to compare the types of cases the court decided to those brought before PMM. PMM arbitrated too few cases in 1695/1696 to allow a meaningful comparison. Therefore, PMM cases from the entire period under investigation were used. These included a total of 159 cases. Of these, 92 concerned debt, 33 estates, 12 land disputes, 3 defamation and 19 miscellaneous issues. The court ledger contains 35 cases and lists dispute causes. Comparing the two revealed that the types of cases the court dealt with were identical to those of PMM. In fact, the correlation coefficient, a statistical tool to measure degree of correlation between two sets of cases, is 1.0, indicating the highest possible correlation. Therefore, PMM offered not merely an alternative legal forum. By focusing on equity, it specialised in an area particularly under-served by the state. Moreover, the pattern of cases brought before PMM resembles that of contemporary courts elsewhere. Across the Delaware Valley in the period 1680–1710, disputes over debts and contracts constituted 82.3 per cent of identifiable issues.Footnote 92 In mid-seventeenth-century London, debt suits accounted for 88 per cent of the business of the court of common pleas, and 80 per cent of that of King's Bench.Footnote 93 Craig Muldrew argued that these figures prove that the courts ‘played an important role in economic life’.Footnote 94 Following this logic, the same must be claimed for PMM.

Did PMM arbitrate disputes in order to compensate for the unreliable courts? We can determine this by comparing monthly meeting practices in different locations. The ideal comparison for Philadelphia is London. London was the biggest port at the time and possessed a sophisticated court system. It was also home to the largest single community of Quakers, counting 5,000–8,000 Friends in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century.Footnote 95 Unlike Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, London Yearly Meeting at the time did not explicitly prohibit Friends from entering law-suits. It, however, repeatedly encouraged Friends to solve disputes by arbitration and ‘avoid the scandal of going to law one with another’.Footnote 96 London Friends were organised into six monthly meetings. For five of them, the complete minutes for the period 1682–1772 survive. Searching these records for arbitration cases for sample years of one in ten reveals that while they did occasionally dabble in arbitration, this was far less common than in Philadelphia. Consider the year 1700. While the London community at the time was at least five times the size of that of Philadelphia, PMM arbitrated nine disputes that year, the five London Monthly Meetings for which records survive, together only one.Footnote 97 What is more, among the Philadelphia minutes of 1690, entries concerning arbitration make up 30 per cent of overall entries. In some months, arbitration constituted the only type of activity entered in the minutes aside from marriages.Footnote 98 Finally, the London Monthly Meetings’ involvement in arbitration remained consistently low throughout the period, with three cases at most, in contrast to the high volatility PMM showed in its involvement in arbitration.Footnote 99 Hence, arbitration was not inherently part of Quaker monthly meetings’ tasks. Instead, PMM must have adopted the practice for a reason.

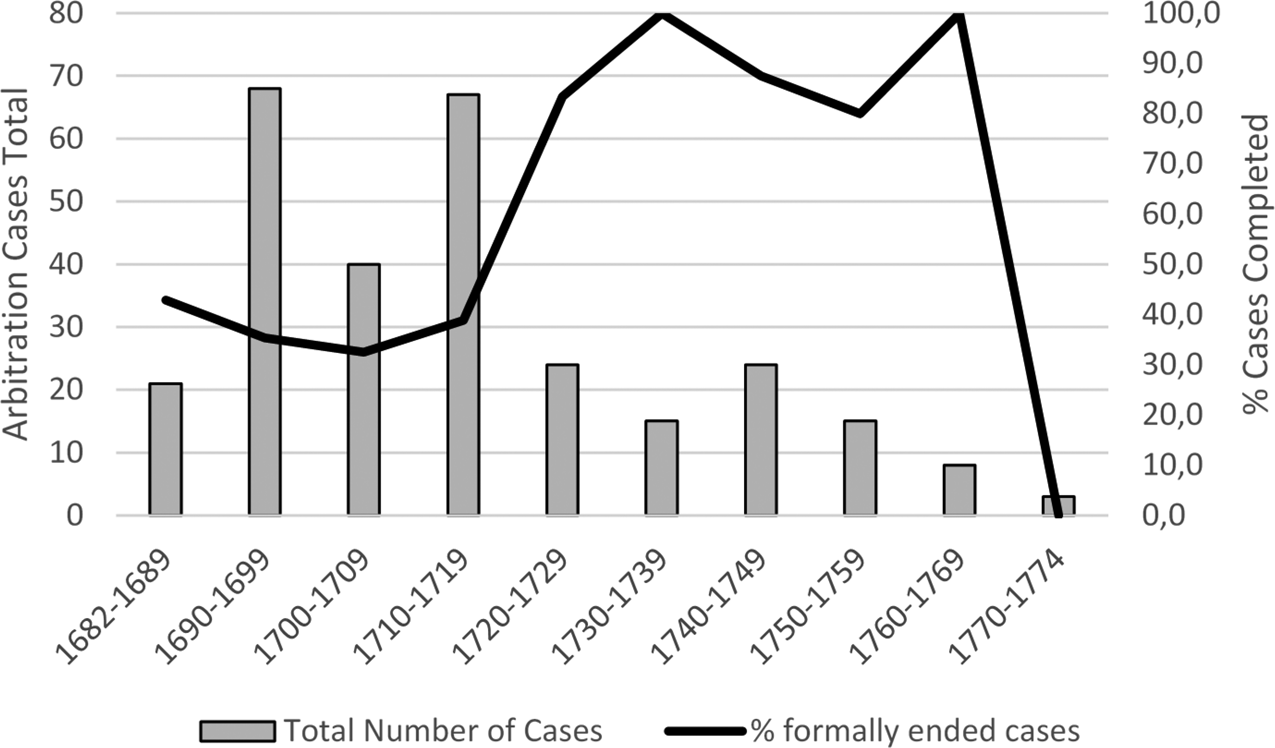

If PMM arbitrated disputes because courts were not reliable, we would expect its involvement in arbitration to vary according to the political situation. Figure 1 shows that the distribution of cases is uneven. PMM's first years saw few cases. Their number increased rapidly towards the end of the seventeenth century. Declining briefly in the early 1700s, they rose again to peak in the 1710–1714 period. They then declined again and reached a nadir in the early 1730s. Rising again briefly during the 1740s, they consequently petered out.

Figure 1. Cases arbitrated by Philadelphia Monthly Meeting.

This trend roughly mirrors the development of political and legal stability in the colony. Within the first years after arrival, Friends learned that the courts were unreliable. Then political conflict began: the crown expropriated Penn, placing the colony under the jurisdiction of non-Quaker New York from 1692 to 1694. Simultaneously, the oath controversy, lasting from the 1690s to about 1720 impeded the courts’ functioning. Penn's 1708 bankruptcy and pending threat to sell the colony until 1718 gave Friends cause not to trust the authorities, including courts. In this context, it is also worth noting that Offutt found an increased frequency of civic contempt across the colony, ‘as courts struggled to maintain their authority’.Footnote 100 Courts’ difficulties to enforce their verdicts gave Friends even more reason to turn to their monthly meeting, instead.

The literature agrees that courts improved significantly from 1720 onwards, as legal instability and political conflict subsided. Importantly, from 1720 to 1736, a court of equity was active in the colony. In this period, PMM's case load receded. This may reflect Friends’ growing trust in the courts. On the other hand, from the 1750s onwards, a major political crisis shook Pennsylvania. During the Seven Years' War, Pennsylvania Quakers quarrelled with the colony's proprietors over military spending. In consequence, Friends eventually withdrew from all public office, including the justice system.Footnote 101 If Friends’ use of PMM for dispute resolution merely mirrored the level of trust in, or access to courts, PMM's case load would have increased again in this period. Yet, it did not. While level of accessibility probably mattered, another factor must have been at play in determining PMM's involvement in dispute resolution. As the next section will show, this factor was PMM's ability to enforce its arbitration awards.

8. How Philadelphia Monthly Meeting harnessed reputation to enforce its verdicts

The final question regarding PMM's arbitration must address enforcement: For a legal institution to be effective, it requires reliable tools to enforce its verdicts. What instruments did PMM possess to ensure Friends honoured its decisions? Three forms of enforcement emerge from the sources.

First, ‘disownment’. This was a form of ostracism, which PMM sometimes applied to Friends who broke its rules or tarnished the Society's reputation. Carli Conklin and Peter Philips attributed much power to disownments, assuming it a harsh measure.Footnote 102 However, if we look at the practice of disownments, a different picture emerges: A disownment consisted of a declaration in front of the community explaining the person's crimes and that PMM no longer considered them a member. Disowned Friends were no longer allowed to preach or receive poor relief. They could however continue to attend meetings for worship, and later apply for re-admission. For pious Friends, membership in the Society was important, and many submitted ‘self-condemnations’ in which they admitted their guilt and apologised. The self-condemnation was publicly read at monthly meetings before the Friend was re-admitted. The nature of the ostracism, as well as reinstatements into membership, suggest that disownments derived at least part of their power from public shaming. The exposure a culprit's misconduct received through the publicity of a disownment caused reputational damage.Footnote 103

PMM recorded hundreds of disownments for disciplinary digressions during the colonial period.Footnote 104 In the context of arbitration, disownment appears 18 times.Footnote 105 PMM actually ‘executed’ a disownment in eight of these instances.Footnote 106 Twice the parties reached an agreement immediately after PMM threatened disownment.Footnote 107 The remaining cases dragged on, some of them occasioning several threats of disownment before disappearing from the minutes.Footnote 108

A second enforcement instrument was PMM's granting plaintiffs permission to approach the public courts. The minutes include 47 such instances. While the Discipline prohibited Friends from entering law-suits without permission, we know that Pennsylvania Quakers litigated regularly without facing repercussions from their monthly meetings.Footnote 109 Yet, Friends sometimes approached PMM, explaining their grievance over another Friend's conduct and requesting ‘liberty to go to law’. If they did not have to fear repercussions for appealing to court of their own accord, why did they bother asking PMM's permission? Most likely, this served to threaten defendants.Footnote 110 By seeking PMM's permission to sue, plaintiffs communicated the seriousness of their intention, while still avoiding the disadvantages of a law suit. PMM met more regularly than the courts, shortening the waiting periods a person wanting to litigate would otherwise have to endure. Approaching PMM first might also save court fees, as the meeting's service was free. As Isaac Norris put it in a letter to a Friend in England, whose claims on an inheritance he was representing: ‘I had thoughts of entering an attachmt and recover it legally but that will be chargeable & therefore apply'd again to our meeting who have appointed Two Ffrds to assist me’.Footnote 111 The 1,717 case of Mary Howard illustrates this further: In that instance, Richard Moore, as attorney to one Henry Childs of Maryland, issued a complaint with PMM against Mary Howard for refusing to settle a debt. PMM appointed two Friends to ‘endeavour to persuade her to pay the money’.Footnote 112 The following month, ‘she appearing justly indebted to the said Childs, the same friends are continued, and desired to put her upon making pay to said Childs ( … ), or otherwise to let her know, that he or Richd. Moore on his behalf may take a legal course against her’.Footnote 113 Four weeks later the case was minuted as ‘ended’.Footnote 114 Apparently, the threat worked. There were also multiple cases which disappeared from the minutes without formal ending. In these instances, we do not know whether the dispute was settled as a consequence of PMM's threat, or whether Friends in fact continued their conflict in court. As Friends employed this method quite frequently, they appear to have thought it useful.

Friends used disownments and law-suits as threats. Both practices involved a high degree of publicity, they shone a light on the conflict parties and their behaviour. This indicates that reputation played an important role in PMM's resolution of disputes. Indeed, the importance of reputation in the early modern world cannot be overstated. Its role in long-distance trade has been discussed above. No less important, a person's reputation determined her or his standing in their local community, both socially and economically. With little currency in circulation, economic transactions, from intercontinental trade to buying bread at the local baker's, were based on credit.Footnote 115 Whether others would grant you credit or not depended on whether they trusted you to repay them. Their trust depended on a person's reputation. If someone's reputation was tarnished, others would refuse to deal with them.

The impact of spoken words is further reflected in the use and practice of law. American colonists turned to courts to salvage their reputations after having been slandered. Slander suits included instances of ‘charging the target with fraudulent or deceptive business practices’.Footnote 116 Mary Beth Norton found that ‘The two epithets most commonly employed by men against other men, “rogue” and “knave”, both implying a lack of trustworthiness’.Footnote 117 In early colonial Pennsylvania, accusations of commercial malfeasance were among the three most common causes of slander accusations.Footnote 118 The frequency of slander suits reflects the damage people feared loss of reputation would do to their social and economic lives.

Colonial courts, in turn, used the force of reputation to punish crimes.Footnote 119 In seventeenth-century Maryland, courts sentenced those convicted of slander to apologise publicly to the person s/he had slandered and explain that their accusations were false.Footnote 120 Pennsylvania law ‘mandated that those found guilty of fraud ( … ) have their names published as frauds and that disorderly people be publicly termed “Breakers of the Peace”’.Footnote 121

A connection between reputation and arbitration has been suggested by Bruce Mann's 1984 study of dispute resolution in seventeenth-century Connecticut. He showed that formal dispute resolution mechanisms replaced informal arbitration as the local population's size and composition changed.Footnote 122 His illuminating research predates more recent work on private order institutions for contract enforcement, and a possible role of reputation mechanisms for the enforcement of arbitration awards remains unexplored. When disputes were arbitrated in early modern Scotland and England, Margo Todd argued more recently, publicity provided by ‘large numbers of witnesses’ ensured that ‘the settlement would be kept, since violating an agreement witnessed by the whole neighbourhood would bring charges of duplicity and undermine reputation’.Footnote 123

It is here that the key to PMM's success as a legal forum lies: Its most powerful tool was the ability to tarnish a malfeasant Friend's reputation. In order to enforce its arbitration awards, PMM deliberately employed reputation mechanisms, in a fashion similar to that of American courts. According to Marc Galanter, the ability to provide stigma is among courts’ most powerful instruments, and courts’ impact on disputes derives largely from their ability to disseminate information.Footnote 124 Thanks to the Atlantic-wide scope of the Society of Friends’ formal organisation, PMM could disseminate information further, making its arbitration particularly useful to long-distance merchants.

PMM developed means to gather, verify and disseminate information about individual Friends’ conduct. First, it appointed and monitored arbitrators. These investigated disputes and reported back to PMM regularly. Through these investigations PMM ensured that the information it obtained was accurate. Next, PMM diffused this information locally and internationally. It discussed cases at its monthly gatherings, which were open to the public. As mentioned above, merchants tried to avoid taking disputes to courts because they feared the damage to reputation this could cause.Footnote 125 PMM made use of this fear. Discussing a dispute at PMM increased its visibility in the community, as well as the (mis-)conduct of the dispute parties. It thereby exerted pressure on the defendants.

PMM, furthermore, transmitted information through the Society of Friends’ Atlantic-wide organisation of meetings. According to its minutes, PMM corresponded formally with other monthly meetings in America and Europe in order to solve conflicts. In 1690, PMM contacted the Monthly Meeting of Hartshaw, Lancashire, regarding the payment of maintenance by some Lancashire Friends to Thomas Hodge in Philadelphia. They asked Hartshaw Friends

that they would be pleased to stir up those Friends concerned to send over ( … ) the interest of the foresaid money for the reasonable charges of the said Thomas Hodges, as also for £21.9s d0 he hath paid for the use of Fairslife Hodges with the interest thereof, which also hath been refused hitherto.Footnote 126

Alternatively, if there was a conflict between a Philadelphia Friend and a Friend belonging to another monthly meeting not too far away, representatives of both meetings would meet to settle the dispute. In 1696, PMM noted:

There being a matter of difference brought to this meeting by Ralph Jackson between himself and Josiah Ferne belonging to the monthly meeting of Derby. In order to the putting an end thereunto, this meeting requests John Kinsey & David Lloyd to meet with two Friends appointed by the monthly meeting of Derby for the same purpose, that they may end it if possible.Footnote 127

Those corresponding monthly meetings would then discuss the conflicts as well, increasing the circle of those who learned PMM's verified information.

Furthermore, many of PMM's officers were merchants. A list of names of those acting as officers in arbitration cases for one year in every ten includes 70 individuals. The sources discussed above allowed for the identification of 39 of these, 55.7 per cent, as merchants. They maintained business correspondence with agents across the Americas and Europe. While their surviving correspondence contains no evidence of their passing on information gleaned specifically from PMM arbitrations, they do share information about each other's conduct of business and character regularly with their correspondents.Footnote 128 Jonathan Dickinson, for instance, appeared as an arbitrator in 1698.Footnote 129 His letters include addressees in London and Jamaica.Footnote 130 Officer Samuel Carpenter traded with Barbados, Samuel Richardson with Boston and New York.Footnote 131 It is unlikely that these merchants, concerned with sharing important information with their correspondents, would have omitted intelligence gleaned from arbitration procedures.

Through its investigations PMM ensured that the information it obtained was more reliable than rumours circling informally. Through the public discussion of this information at monthly meetings in Philadelphia and elsewhere, and its ‘leaking’ by officers, the Society of Friends reinforced reputation mechanisms.

PMM, moreover, showed concern over the reputational damage its procedures might cause. In 1687, John Ithell accused merchant Robert Turner of malfeasance. PMM thereupon ‘appointed some friends to hear the matter in difference between them’. These Friends reported back that, according to the best of their judgement, the said John Ithell had ‘wrongfully charged him the said Robert Turner’.Footnote 132 PMM ordered further investigations, and two months later, it directed several Friends to ‘draw up a certificate ( … ) to be sent to England & Ireland for the clearing him (Robert Turner) of those scandalous reports that hath been spread concerning him in those parts to his defamation’.Footnote 133

A comparison of the development of arbitration cases with Philadelphia's population reveals more evidence. As discussed above, there is a certain correlation between the numbers of cases PMM arbitrated, and political crises in the colony. Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate a stronger, negative correlation between three factors: PMM's case load and case outcomes, on the one hand, and Philadelphia's demographic development, on the other.

Figure 2. Completed arbitration cases. Sources: Haverford Special Collections, Philadelphia Monthly Meeting minutes and Billy G. Smith, ‘Death and life in a colonial immigrant city: a demographic analysis of Philadelphia’, The Journal of Economic History 37, 4 (1977), 863–89.

Figure 3. Meeting arbitration cases and Philadelphia population. Sources: Haverford Special Collections, Philadelphia Monthly Meeting minutes and Billy G. Smith, ‘Death and life in a colonial immigrant city: a demographic analysis of Philadelphia’, The Journal of Economic History 37, 4 (1977), 863–89.

From the late 1710s onwards, PMM's case load decreased dramatically. Moreover, cases’ outcomes changed. Overall, 48 per cent of cases disappeared from the minutes without a formal ending, that is, the minutes do not mention them for 12 consecutive months. This number closely resembles that for Delaware Valley courts.Footnote 134 Figure 2 shows that the formally ended cases were distributed unevenly. Constituting roughly 50 per cent until about 1720, their proportion increased rapidly thereafter.

The decline in PMM's case load and the number of cases without formal ending coincided with the exponential increase in migration to Philadelphia. Local Quaker merchant James Logan in 1717 described this development as follows:

… there are divers hundreds, arrived here who have not one word of English and bring no credentials with them ( … ) the numbers of these strangers have given some uneasiness to the inhabitants here, & will encrease it, if they continue thus their swarms.Footnote 135

The changes in PMM's handling of cases were not due to its limited capacity. It expanded its work dramatically during this period. This is evidenced by the number of pages of minutes for each session. While the Philadelphia Quaker population roughly doubled between 1690 and 1760, the length of PMM's minutes increased about 26-fold.Footnote 136 This demonstrates an intense increase in PMM's effort of administration per capita. However, it chose not to use this extra capacity for conflict arbitration, instead focusing on other matters.

The new immigrants differed from their predecessors. First of all, they were not Quakers.Footnote 137 Ergo, they would not participate in monthly meetings and witness arbitration proceedings there. They were also less likely to learn of information discussed in Quaker meetings from other Quakers. Additionally, many of them were German and spoke no English.Footnote 138 As Jack Marietta and G.S. Rowe put it, the new arrivals’ ethnic and linguistic diversity ‘diluted the homegeneity of the province’.Footnote 139 Population growth, combined with the change in religious and linguistic composition, must have posed a barrier to the flow of information. Thereby it lowered the possible impact of reputation mechanisms. Social pressure exerted through everyone in town learning about alledged misconduct would have diminished significantly. The degree of public shaming for malpractice diminished, and thereby the reputation mechanism's power to pressure conflict parties into giving in and finding informal solutions. Consequently, PMM's power to enforce contracts faded. Friends noticed this and began searching for alternative forms of contract enforcement. As discussed above, Pennsylvania's courts improved from about 1720 onwards, as political and legal stability finally arrived in the colony. Likely, Friends now turned to the courts to solve disputes between them.

9. Conclusion

Research on Atlantic trade expansion has been strongly influenced by the New Institutional Economists. For the NIE, long-distance trade expansion is contingent on the replacement of private order, communitarian institutions by public order institutions provided by the state. Public order institutions could better enforce contracts and protect property rights because they were backed by the state, who, holding sovereignty throughout its territory, would enforce court's verdicts. This lowered transaction costs and enabled trade to expand. In the American colonies the state was underdeveloped, public courts unreliable and the collection of debts notoriously difficult. In spite of this, trade in the Atlantic grew a great deal. Philadelphia Quaker merchants were prominent in the colonial trades from the colony's earliest days, and the city soon emerged as one of North America's greatest ports. In the face of its weak institutions, Philadelphia's commercial ascent needs explaining.

This paper has argued that the solution to the puzzle of Philadelphia's success lies in the realm of religion. Religion as the basis for informal trading networks in the Atlantic is well established. The PMM records, however, show that religion did more than provide the basis for informal networks. It also supported trade through formal institutions. PMM arbitrated commercial disputes among merchants. It specialised in equity, a branch of law that while important for the enforcement of commercial contracts, was underserved in the colony. PMM enforced its arbitration awards by highlighting commercial conflicts within the community. It did this locally, through its monthly gatherings, as well as through its formal organisation of meetings across the English/British Atlantic world. This placed pressure on the parties: In order to limit reputational damage, they had to come to an agreement quickly. As Philadelphia grew in size and diversity, the flow of information through informal channels became more difficult. PMM lost the power to enforce its decisions, and consequently its popularity among Friends.

PMM acted as a legal forum that specialised in settling commercial disputes between its members. In so doing, the Society of Friends de facto provided law in the colony. In colonial Pennsylvania, ‘Quaker law’ existed as an alternative to ‘state law’. As Quaker merchants resorted to PMM often, we can deduce that it played an important role for their businesses and thereby the growth of Philadelphia's trade. Rather than a hinderance, legal fragmentation was at the root of colonial Philadelphia's commercial success.

What are the implications of this finding for research on pre-modern trade expansion? The growth of pre-modern long-distance trade depended primarily on two sets of actors. These were first, the chartered trading companies, and second, religious diasporas.

It is well-established that the English East India Company (EIC) and Dutch East India Company (VOC) had sovereignty in Asia and jurisdiction over English and Dutch subjects in ‘their’ territories.Footnote 140 They made and enforced law through their own institutions. While EIC regulations were formally supposed to be in accordance with English law, de facto company legal practice was independent.Footnote 141 In practice, European commerce in the Indian Ocean depended largely on the law of non-state actors.

Religious diasporas formed the second spearhead of trade expansion. The most prominent of these included Armenians, Sephardim and Quakers. Sebouh Aslanian has located an institution very similar to the Quaker Monthly Meeting in Safavid New Julfa. The ‘Assembly of Merchants’ supported Armenian merchants’ global trade networks by gathering information about merchants’ behaviour overseas and disseminating this among the community. Thereby it reinforced reputation mechanisms.Footnote 142

Research by Nuala Zahedieh, Jessica Roitman and Hugo Martins has shown that Sephardi merchants in Europe and the American colonies also benefited from private courts. Communities from Hamburg to Curacao elected boards of elders – the Mahamad – who ensured community members’ compliance with religious rules. They also arbitrated commercial conflicts according to formally written rules. How they enforced their decisions, and what role reputation played in this context has yet to be fully explored. The records do, however, show striking similarities to PMM in terms of the causes of conflicts they dealt with and the procedures they followed.Footnote 143 This suggests that the creation of legal forums for commercial dispute resolution was not restricted to the Society of Friends, but a common feature of pre-modern religious trading diasporas. If so, this would help explain the prominence of religious diasporas in long-distance trade.

It would appear that non-state law played an important role not only for Philadelphia merchants, but pre-modern trade expansion in general. Why was that? Colonies, whether those of European states or trading companies, were more diverse than societies in the European mother countries. Lauren Benton and others have pointed out that this diversity gave rise to conflicts which were novel to the metropole, and for which European law had no ready solutions. Law developed locally by those with first-hand experience of colonial life and economy was more likely to serve the colonists’ purposes. It was also cheaper for metropolitan governments than developing new legal structures and forcing these upon colonial populations.

Second, the diaspora communities so crucial to trade expansion often had a history of oppression. When first settling in Pennsylvania in the 1680s, Friends were still suffering persecution in England. While they had the privilege of shaping legal institutions in Pennsylvania, the ‘oath controversy’ and threat of expropriation suggested that the situation could turn with public courts becoming instruments of oppression once again. The dissenting protestant founders of other American colonies shared these experiences. Sephardi Jewish merchants carried with them the heritage of the inquisition and flight from the Iberian Peninsula. While settling in various European cities, they continued to face discrimination and harassment from both the public and state authorities. These minorities’ experience with state courts was often one of imprisonment and property confiscations – a far cry from the image North et al. paint of the helpful institution that enforces contracts and protects property rights. Under these circumstances, it made sense for persecuted minorities to prefer alternative legal forums to public courts.

A final reason for resorting to non-state law lay in European trade policy. Mercantilism forbade subjects to trade with destinations outside the empire, heavily limiting commercial opportunities. We now know that merchants often ignored these prohibitions and that illegal inter-imperial trade was substantial.Footnote 144 Bernard Bailyn called smuggling ‘integral to the working of the Atlantic system’.Footnote 145 Illegal commerce depended on the enforcement of contracts, too. Self-evidently, merchants could not turn to state courts for help with errant payments or faulty wares. Non-state legal forums would have been one way to overcome these challenges.

Philadelphia's Quaker legal forum suggests that we need to reassess the role of both religion and the state for trade expansion. Contrary to what North et al. have argued, the rise of strong states and public order institutions was not the basis for early modern trade expansion. Religious diasporas leading Atlantic trade expansion, including the Quakers, built their trading empires by drawing on alternative law. Rather than strong central governments, the key to trade expansion and economic growth in the Atlantic was institutional diversity.

Acknowledgements

For their input and support I thank Yadira Gonzalez de Lara, Daniel Strum and the participants of the ‘Institutional foundations of pre-modern long-distance trade' meetings, Nuala Zahedieh and the participants of the ‘Economic and Social History of the Early Modern World’ seminar, Amalia Kessler, Patrick Wallis, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Alberto Winterberg and three anonymous reviewers.