Gambling, an ordinary leisure activity for over 70% of Britain’sFootnote a adult population, can nevertheless become problematic for some (Reference GriffithsGriffiths 2007). There is emerging consensus that gambling, akin to substance addiction, is best viewed as occurring on a spectrum of severity, ranging from social gambling, through problem gambling, to pathological gambling or gambling addiction, although there is no universal consensus on the boundaries between these designations. Sadly, in Britain, treatment provision for problem gamblers is scant and problem gambling has failed to attract serious interest from healthcare professionals, policy makers and commissioners.

Epidemiology: the British context

Problem gambling, viewed as gambling that disrupts or damages personal, family or recreational pursuits (Reference Lesieur and RosenthalLesieur 1991), is estimated to affect between 360 000 and 451 000 people in England, Wales and Scotland – around 0.9% of the adult population (an increase of 0.3% over the past 3 years). A further 7.3% of the adult population are deemed at risk of developing problem gambling in the future (Reference Wardle, Moody and SpenceWardle 2010). Gambling cuts across age, gender, class and culture; young people and ethnic minorities are likely to be particularly vulnerable (Reference Wardle, Moody and SpenceWardle 2010). International research strongly suggests that increasing the availability of gambling opportunities will result in increased rates of problem gambling and gambling-related problems (National Research Council 1999). Britain’s policy makers, gambling regulators, service commissioners and service providers should note this, as Britain has very liberal gambling laws (in the form of the Gambling Act 2005), a rapidly expanding online gambling industry and is awaiting the opening of casinos across the country.

Gambling and its consequences

Problem gamblers suffer high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, including depression, anxiety, substance misuse and personality disorders (Reference Petry, Stinson and GrantPetry 2005). Severe gambling disorder is also associated with several stress-related and other medical disorders (e.g. cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal), with resultant increased use of medical services (Reference Morasco, Pietrzak and BlancoMorasco 2006). Excessive gambling often results in financial losses, leading to debts and bankruptcy. Individuals may commit crime to fund their addiction. As the gambling addiction takes hold, employment and employability may suffer significantly. Moreover, it is estimated that for every pathological gambler, between 8 and 10 others are also directly affected, including family, friends and colleagues (Reference Lobsinger and BeckettLobsinger 1996). Spouses often bear the brunt, and instances of domestic abuse and violence are common (Reference Mulleman, Denotter and WadmanMulleman 2002). Children of gamblers have been found to have high rates of behavioural problems, emotional difficulties and substance misuse (Reference Jacobs, Marston and SingerJacobs 1989).

Why Britain should care more about its problem gamblers

Our clinical experience and international research evidence indicate that very few problem gamblers seek treatment and, even if they do, they present to non-gambling support services with symptoms that may not be directly attributable to gambling. This, coupled with the lack of awareness of the nature of gambling-related harm that we see in healthcare professionals, and a lack of dedicated services for people with gambling problems, often results in problem gambling going unrecognised and associated needs unaddressed: problem gamblers remain largely ‘hidden’ and ignored. Given the prevalence of problem gambling, its potential for harm to the individual, family, community and society, and the current significance of these issues for Britain, it is disappointing that treatment provision is at best patchy and at worst nonexistent.

Gaps in current service provision

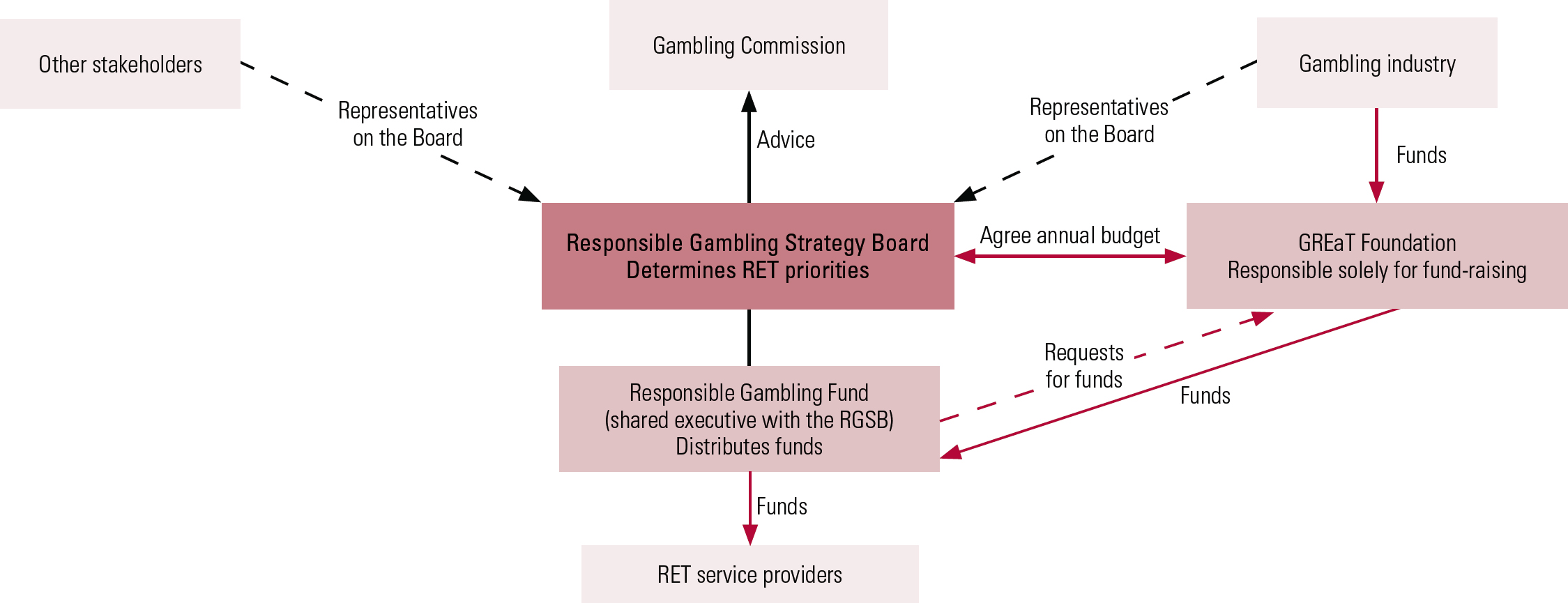

Treatment for problem gamblers in Britain is almost exclusively provided through the non-statutory or third sector, and largely funded via the Responsible Gambling Fund (RGF). The RGF disperses its funds via three work streams – research, education and treatment. The RGF’s fund-raising body is the Gambling Research, Education and Treatment (GREaT) Foundation (Fig. 1).

The largest provider of gambling treatment in Britain is GamCare, a non-governmental organisation and charity that ‘provides support, information and advice to anyone suffering through a gambling problem’ (www.gamcare.org.uk). Based in London, it offers services both directly and through its partner agencies in several parts of Great Britain, although its geographical coverage is by no means comprehensive. Other non-statutory treatment providers include Gamblers Anonymous (www.gamblersanonymous.org.uk), a self-help group network modelled on Alcoholics Anonymous but operating on a considerably smaller scale across the UK, and the Gordon Moody Association (www.gordonhouse.org.uk), which offers only limited residential and online help. Finally, Gamble Aware (www.gambleaware.co.uk) is an internet portal to information on gambling and sources of help for problem gamblers. It is run by the gambling industry and administered by the GREaT Foundation.

This system of service provision has numerous limitations, despite the best efforts of current providers. As an indicative regional example, and using a mixed qualitative–quantitative study (unpublished), we mapped out the scope and range of gambling services provided by non-statutory agencies in the West Midlands, and identified the following limitations in treatment provision:

-

• no coherent policy or drivers (such as exist in the field of substance addictions)

-

• lack of clearly defined model/s of care (such as a tiered-care approach)

-

• inadequate engagement with primary care and specialist mental health services

-

• absence of regional commissioning impetus

-

• competition for resources with drug and/or alcohol treatment services

-

• lack of integrated care pathways.

FIG 1 The voluntary arrangements of fund-raising and the funding of research, education and treatment (RET). The Responsible Gambling Strategy Board (RGSB) forms part of a tripartite structure comprising a single-purpose fund-raising body, the Gambling Research, Education and Treatment (GREaT) Foundation; a distributing body, the Responsible Gambling Fund (RGF); and the RGSB, which determines the strategy and priorities for RET and passes a strategic funding framework to the RGF. The RGSB and RGF work closely together, but are independent of each other. Redrawn with the kind permission of the GREaT Foundation.

Statutory-sector services for problem gamblers have very limited capacity. For example, there is only one specialist National Health Service (NHS) treatment centre for problem gamblers in England and Wales, the Central and North West London (CNWL) National Problem Gambling Clinic (www.cnwl.nhs.uk/national_problem_gambling_clinic.html). The clinic receives over 400 referrals a year, and uses a multidisciplinary, evidence-based treatment approach. It is also the national hub for the UK Problem Gambling Research Consortium (H. Bowden-Jones, personal communication, 2011).

A report on gambling addiction and its treatment in the NHS commissioned by the British Medical Association specifically called for treatment for problem gambling to be provided under the NHS (Reference GriffithsGriffiths 2007). It also highlighted the need for better screening for gambling problems in primary care, mental healthcare, and in substance misuse, probation and prison settings, and more education and training of general practitioners (GPs) in the diagnosis, referral and treatment of people with gambling problems. Despite this, progress has been disappointingly slow and, to date, the health sector and particularly the NHS has ignored calls to fund more dedicated services. That said, offering considerable promise in this regard is the recently announced (March 2011), albeit RGF-funded, Royal College of General Practitioners’ commitment to develop and implement a 3-year training programme for GPs to support people with gambling problems (Responsible Gambling Fund 2011).

A crucial factor in successfully setting up and sustaining treatment services is the funding mechanism that supports them. Here, as opposed to the environment prevailing in relation to substance addictions, gambling treatment services are effectively exclusively dependent on funds derived from voluntary contributions made by the gambling industry, as outlined in Fig. 1. Note, however, that the gambling industry in Britain has an annual turnover of over £80 billion (2006/2007 data) and the government receives millions of this in tax revenue each year. Also note a stark contrast here with expenditure in the field of drug misuse: the government spent £581 million in 2008/2009 to treat approximately 250 000 Class A drug users in England alone (National Audit Office 2010).

Opportunities to improve service provision

In planning to improve service provision for people with gambling problems and those around them, four key questions emerge:

-

1 Who should commission these services?

-

2 What should these services look like?

-

3 Is there an ethically sound model for funding?

-

4 Who should provide these services?

Who should commission gambling services?

As it stands, the RGF (funded by the gambling industry) commissions most of the (predominantly third-sector-led) gambling treatment services in Britain. This carries the limitation of an exclusive reliance on the industry’s generosity. In our view, given that problem gambling is a public health issue, the NHS should commit and invest more. This by no means diminishes the role, scope and value of the non-statutory sector. In light of the latest White Paper on the NHS (Department of Health 2010), commissioning roles are set to shift away from primary care trusts to GPs, so the latter will have an important part to play. We see GPs as having dual purchaser and part-provider roles, including screening, offering brief interventions and referring problem gamblers to specialist services as needed (Reference George and GeradaGeorge 2011). Given the above-noted capacity of the RGF and the Department of Health/NHS as commissioning bodies, perhaps it is reasonable – and even opportunistic – to propose a co-commissioning model, part NHS and part RGF.

What should a commissioning framework for gambling services look like?

Here it is useful to conceptualise problem gambling as a public health issue (Reference Adams, Raeburn and De SilvaAdams 2009) and to adopt a three-level approach for the prevention of gambling-related problems:

-

1 primary prevention: measures aimed at preventing gambling from becoming a problem, such as raising awareness, education about potential for harm and other public health approaches;

-

2 secondary prevention: measures targeted at early diagnosis and treatment, involving screening in settings such as primary care and mental health services, followed by brief specialist interventions for gamblers and their families;

-

3 tertiary prevention: specialist and intense psychological and psychiatric interventions for problem gamblers, support for their families, and so on.

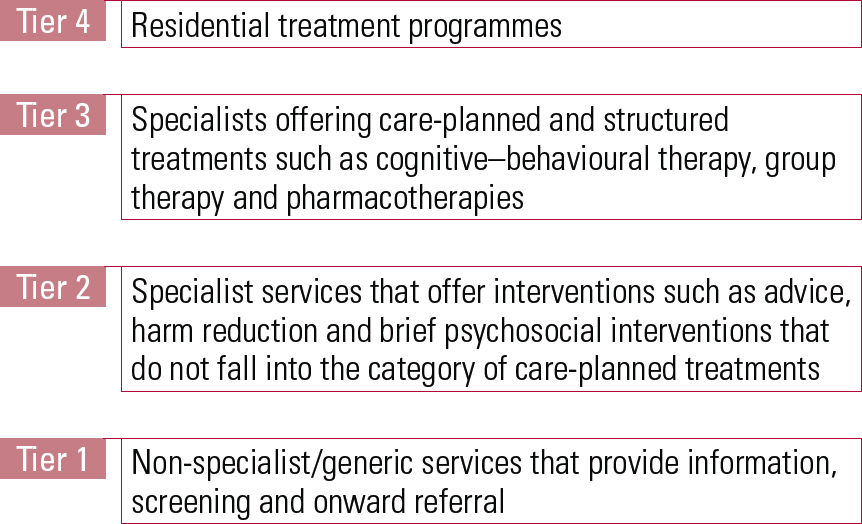

An ideal framework for the commissioning and provision of treatment for problem gambling would be a four-tiered service delivery model such as that used in the field of drug misuse (outlined in Fig. 2).

FIG 2 A four-tier service delivery model for the treatment of problem gambling (after National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse 2006).

If resources are at a premium, as is currently the case, it might be appropriate to invest more in Tier 1 (gambling-related information and advice, screening and referral by non-specialist/generic agencies) and Tier 2 (brief interventions in more specialist settings and support for gamblers’ families) services. Very recently (2010/2011), the RGF has made a promising start in this regard by commissioning three time-limited early intervention pilots across Britain. Furthermore, as noted earlier, it has recently commissioned the Royal College of General Practitioners to train GPs in helping problem gamblers in primary care. Such measures should, however, run alongside appropriate regulation and monitoring of the gambling industry and its future expansion. Further consideration must also be given to setting up additional Tier 3 specialist treatment centres for gamblers with complex problems who require structured, care-planned treatment. Viewing problem gambling as a public health problem, it is equally important, albeit more challenging, also to implement an effective public health approach to addressing the harms of gambling (Reference Adams, Raeburn and De SilvaAdams 2009).

Is there an ethically sound model of funding?

To be ethically sound, the provision of treatment should be independent of the gambling industry: ‘independent’ providers could be the government (via the NHS) and/or the third sector. However, such complete independence in the current financial climate may not be entirely realistic. A pragmatic and workable solution would be a combined treatment-funding stream, with both the government and the industry as donors, although the imposition and monitoring of a strict ethical code of practice for the industry’s involvement would be vital.

Who should provide these services?

The answer to whether treatment should be offered by the NHS or by non-statutory services need not necessarily be an either/or one: partnerships between statutory and non-statutory agencies are increasingly being recognised as a good way forward (Reference George, Boulay and MackinnonGeorge 2009). Our own experience in providing services for alcohol and drug misusers in Birmingham and Solihull lends further support to such a model, in demonstrating cost-effectiveness, patient-centredness and sustainability. Other significant benefits of such an integrated model of service delivery include joined-up care pathways, efficient care coordination and a seamless service.

Much as we can and should draw on the international evidence base, there is no denying the importance of further UK-generated research. However, this should not delay better treatment provision for problem gamblers. We hope that the immediate future will see more clinician and government interest, treatment guidelines, resource commitment and the development of national policies.

Conclusions

One thing is very clear: the current level of treatment provision for problem gambling in Britain is grossly inadequate. Of lesser clarity is the question of who is – partly or wholly – responsible for improving the situation. Is it health professionals, policy makers, commissioners, the gambling industry or a ‘coalition of the willing’ from among these constituencies? Whatever the case, there is an obvious need for all parties to acknowledge gaps in current service provision, consider these as opportunities and work together to plug them in the immediate future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jim Fearnley, Jim Orford and Nancy Petry for their comments on drafts of this manuscript, and Henrietta Bowden-Jones for her support.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.