In 1975, the local savings bank in Wilhelmshaven, a medium-sized city in Germany'sFootnote 1 north-western corner, published an image brochure, which praised the city's past and its future prospects. The first page is full of grandiose slogans, such as ‘Germany's alternative to Rotterdam’, ‘green city by the sea’ or ‘horizon of national economic opportunity’.Footnote 2 The third slogan is particularly interesting since it denotes the contemporary optimism about the city's future. This optimism rested on the successful attraction of large-scale complexes from the petrochemical industry, which began in April 1970. After the first contract about settling a plant processing alumina was signed, local media and politicians were jubilant: ‘April 9th is the beginning of a new era. Industrialization has reached the Jade.’Footnote 3

This article will scrutinize the industrialization of Wilhelmshaven from the vantage point of such optimistic claims. It argues that these claims not only accompanied the industrialization process, but that optimism played a major part in its justification and perpetuation in spite of crises and problematic developments throughout the 1970s. The interplay of optimism and industrialization is indicative of an interesting discrepancy between the history of Wilhelmshaven in the 1970s and recent historiography about that decade. In his 2009 lecture at the German Historical Institute in London, Hartmut Kaelble summarized the scholarship on the 1970s in Europe and pointed out two major trends. The 1970s are either understood as ‘the dark interpretation of decline, of crisis, of disillusionment’ or interpreted as the beginnings of the present, ‘of new realism or even of promise’.Footnote 4 For the historiography on Germany, Kaelble's assertion is fairly accurate, even though most approaches to the 1970s are more balanced than his dichotomy suggests.Footnote 5

Both trends in historiography emphasize significant changes in production, labour and consumption, usually connected to notions about the changing role of industry. There are certainly good reasons for understanding the 1970s in Germany as a watershed in this respect. For the first time, the tertiary sector contributed more to the German gross domestic product than the industrial sector. Furthermore, the number of industrial workers continually declined from 1975.Footnote 6 These changes and the accompanying contemporary literature from various academic disciplines fostered the notion of an emerging post-industrial society and processes of de-industrialization.Footnote 7 Even though both diagnoses have recently received criticism and readjustment,Footnote 8 notions of the 1970s as the first de-industrializing decade prevail.

This might be due to contemporaries’ tendency to describe this process – and change in general – with the rhetoric of crisis.Footnote 9 As André Steiner pointed out, the contemporary experience of economic change was closely connected to such diagnoses. A case in point is the economist and ‘innovation researcher’, Gerhard Mensch. He identified the ‘drift of the structural change’ as the core of the crisis.Footnote 10 Even though most diagnoses remained blurry and the 1970s saw a wide variety of them, it seems reasonable to put an emphasis on contemporary perceptions of crisis when investigating the industrialization of Wilhelmshaven. This is even more so, considering Wilhelmshaven received the so-called ‘first oil crisis‘ in a spirit of optimism and, hence, sits uneasily with diagnoses of a ‘new era of “uncertainty and crisis” due to the global currency system's collapse and the oil shock of 1973’.Footnote 11

The latter serves as a popular caesura in German historiography on the 1970s and beyond. ‘The shorter the text, the more likely is a reference to the oil crisis as a factor or at least indicator for a substantial change from euphoric hopes of the boom years towards a pragmatic crisis management’,Footnote 12 as Rüdiger Graf characterizes the general trend in the majority of scholarship on the 1970s. The same tendency seems to prevail in German urban history, where the oil crisis is usually used as a means for periodization.Footnote 13 In addition to the interest in the peculiar mix of optimism and industrialization in Wilhelmshaven, this article thus provides a contribution to analysing perceptions of crises in cities beyond the well-established narrative of ‘urban crisis’.Footnote 14

This article is arranged in chronological order. After some preliminary remarks about Wilhelmshaven's history until the end of World War II, the interplay between industrialization, its perception and perceptions of crisis is discussed in four steps. In the first section, the years between the successful attraction of the very first industrial project and 1973 are scrutinized as a prelude to the first oil crisis, whose perception is discussed in the second section. Similar to the first section, the third section also forms a prelude. In the years between 1974 and 1980, optimism about the future collided with a disenchanting present. The accumulation of negative developments into another crisis and its effects on the industrialization of Wilhelmshaven are discussed in the fourth section.

As secondary literature about Wilhelmshaven's social and economic history after World War II is scarce, the article is predominantly based on primary source material, drawing upon published accounts as well as concrete developments in the city's industrial makeup. For the former, newspaper articles as well as commercial and promotional material from the municipal archives are consulted. Even though these sources have limitations for an in-depth analysis of the individual citizens’ experience, they provide at least a well-rounded picture about publicized accounts and official representations of optimism. The concrete measures for Wilhelmshaven's industrialization were a focus of the local newspaper reporting. In addition to that, political, administrative and academic sources are consulted.

‘The emperor's most favourite child’ – contextualizing Wilhelmshaven

Among the numerous slogans, the brochure of the local savings bank also carried the claim ‘The emperor's most favourite child’,Footnote 15 which points towards Wilhelmshaven's origins in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 16 In the mid-1850s, Prussia bought the region where Wilhelmshaven would be situated to build a naval base. In 1869, the site of the base was called Wilhelmshaven for the first time, named after Wilhelm I. In the constitution of the German Empire, Wilhelmshaven was declared as the country's naval base for the entire North Sea fleet in 1871. Two years later, it gained town privileges.

It is evident that the city benefited enormously from its close connection to the navy – at least in times of military build-up, such as Wilhelm II's policy of naval expansion or the years before both World Wars. It is almost similarly evident that destruction and military demobilization after both wars significantly marred the city's attractiveness. Between 1910 and 1916, the population dropped from 35,000 to 21,000 inhabitants; the years 1939 and 1945 saw a drop from 125,000 to 89,000. In the following years, the city saw a slow but steady growth to 104,000 inhabitants in 1973. Afterwards, the population dropped more or less steadily to 75,000 in 2015.Footnote 17

Up until 1956, when the rearmament of the Federal Republic of Germany led to a return of the navy, the port was out of use due to severe destructions and Allied prohibitions.Footnote 18 The year not only marked the return of the navy but also Wilhelmshaven's first successful attraction of a seaward company: the Nord-West-Oelleitung GmbH (NWO), a corporation of several oil companies, which planned and constructed a jetty and a pipeline for landing oil at Wilhelmshaven and transporting it to the refineries in the Ruhr area and beyond. The crucial factor for both the NWO and the navy was the very deep waterway of the Jade, where Wilhelmshaven is situated. Yet, despite this locational advantage, further large-scale seaward companies or industries did not find their way to the north-west until the 1970s. The navy and Olympia, a manufacturer of office machines from nearby Roffhausen, which was beyond city limits, remained the main employers. While both employers were of great importance to the local labour market, they posed a fairly important fiscal problem for the city, too. Neither the navy nor Olympia were taxable in Wilhelmshaven. This problem was supposed to be solved by attracting capital-intensive industries in the 1970s.

Prelude I: ‘breakthrough towards a coastal seat of industry’ – Alusuisse and Mobil Oil

In April 1970, representatives of the city as well as from the federal and Lower Saxon state governments signed an option contract with the Swiss company Alusuisse, which planned to build a plant for processing alumina. The Alusuisse project is characteristic of three general traits in the city's industrial history. First, Wilhelmshaven did not undergo a process of a broad industrialization with a diversified portfolio. Isolated from Germany's main markets,Footnote 19 the city could not provide a reasonable market for capital goods, as representatives of both the cityFootnote 20 and industry argued. Thus, the city targeted extractive industries, relying on bulk cargo such as oil, coal, liquid gas and sodium chloride. To these industries, the city successfully marketed itself as an attractive deep water harbour, as a contemporary study found.Footnote 21 Secondly, the Alusuisse complex was supposed to be built on the Rüstersieler Groden, a polder area that was developed in the 1960s. This was in keeping with German post-war urban planning, which demanded a strict separation between living, business, leisure, and industry. In Wilhelmshaven, the goal was to ‘develop industrial sites at the city's lee side in the east’.Footnote 22

Thirdly and most importantly, the focus was solely on capital-intensive projects. These were supposed to create business tax revenues and solve the city's financial problems. According to the local newspaper, the company intended to invest roughly 5 billion Marks (£550 million).Footnote 23 Since administration and politics calculated that every 100 million Marks (£11 million) of investment would generate 1 million Marks (£110,000) of business tax revenue,Footnote 24 the rumoured 5 billion more than compensated for the poor impact the project would have on the local labour market. At the project's first expansion stage – which it never exceeded (see below) – only eighty new jobs were going to be created. Furthermore, almost nobody from the city or the region, with the exception of highly skilled technicians and scientists from all over Germany, were going to be employed.Footnote 25

The poor effects on the labour market did not impede the enthusiasm that swept over huge parts of Wilhelmshaven in the spring of 1970. When the contract was signed, newspapers and politicians rejoiced. The Wilhelmshaven part of the Nordwest Zeitung from the nearby city of Oldenburg saw a ‘breakthrough towards a coastal seat of industry’,Footnote 26 the mayor spoke of the ‘breakthrough towards industrializing Wilhelmshaven’,Footnote 27 and the Wilhelmshavener Zeitung (WZ) headlined ‘Wilhelmshaven turns into an industrial centre’.Footnote 28 The successful attraction of the Alusuisse project even made headlines with the established broadsheet newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung: ‘A billion Marks project for Wilhelmshaven’.Footnote 29 In Wilhelmshaven, the year 1970 abounded with further optimistic and enthusiastic receptions of the contract, which was finalized in September.Footnote 30 Accordingly, the project featured prominently in an optimistic article about the future 1970s, published on New Year's Eve in the WZ.Footnote 31

Yet, there was some criticism of the project. A group of environmentalists, which had formed in opposition to a titan-welding plant in the mid-1960s, now strongly opposed the Alusuisse project. In addition to damage to the Jade's eco-system, they disputed the project's economic relevance. Rather than supporting large-scale projects, they urged the city to invest in small- and medium-sized, labour-intensive businesses. In his speech about the municipal budget plan for 1972, chief-municipal director, Gerhard Eickmeier, fiercely defended the project against the criticism. His speech indicates that support for and enthusiasm about the project significantly exceeded the realm of local media: ‘City council, the unions, the trade associations, and the district's craftsmen association’Footnote 32 were in agreement that the project was valuable and important for Wilhelmshaven.

The value and importance attached to the project was in part due to the hopes for its pull-effects, as the mayor put it in May 1971. ‘World-renowned companies’, he told the WZ, ‘have already put out their feelers to Wilhelmshaven.’Footnote 33 Two of these companies, Amoco and Mobil Oil, looked into building refineries there.Footnote 34 A year later, a contract between the city and Mobil Oil was signed. Similarly to the reception of the Alusuisse project, the refinery became a point of reference for optimism and hope. Again, the press reported about huge sums to be invested,Footnote 35 the German chancellor called it an ‘impressive example of successful regional politics’,Footnote 36 and an increase of job opportunities was anticipated.Footnote 37 Unlike Alusuisse, which was a lot more low-key, Mobil Oil chimed in with the optimistic crescendo. In brochures distributed to almost every household, the company praised itself for its ecological precautions and the positive effects the refinery would have on the city's economic structure.Footnote 38 In addition to the immediate effects on the tax revenue, Mobil Oil suggested, it would have pull-effects on other companies and, thus, create further job opportunities beyond the refinery.Footnote 39

Wilhelmshaven's ‘breakthrough’, however, did not contribute to a significant growth of the job market or its economy in general, as a critical report, commissioned by local businesses, found.Footnote 40 Despite these findings, the ongoing criticism of the environmentalists, and the obvious shortcomings in terms of the labour market, the early 1970s had one important effect beyond business tax revenue: the successful attraction of both capital-intensive projects instilled a firm belief in the city's potential of overcoming the structural handicaps and to become a prosperous centre of industry. Rather than marring it, this belief was even fostered by the oil crisis.

Anticipation, validation and optimism: the first oil crisis

In October 1973, two crucial events strongly affected the global oil market and the countless economic players depending on oil. After a controversy between the Organization of the Petrol Exporting Countries (OPEC) and various oil companies could not be solved, the OPEC raised the price for oil. As a result of the Yom Kippur War, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) imposed an import embargo on several countries that they deemed to be in support of Israel.Footnote 41 Combined, both events constituted the so-called ‘first oil crisis’. In contrast to most assumptions about its historical impact on the ‘Western World’ in general or Germany in particular, Wilhelmshaven did not experience the oil crisis as a problem. On the contrary, even though the city's economic backbone relied heavily upon the turnaround of oil, local media, politicians, business and administration reacted surprisingly appreciatively.

In the wake of the crisis, an option contract about a liquid gas terminal was signed with a group of investors. This project had been discussed since 1971, but never made it beyond that stage until November 1973. To the local newspaper, these new developments were closely connected to the oil crisis, since the ‘terminal would have been necessary without the crisis, the current crisis just makes it all the more urgent’.Footnote 42 A similar take on the oil crisis as a bearer of the city's industrial future can be found in a letter local businessman Heinz Roscher sent to the mayor in January 1974. He detailed the local economy's ideas of reviving the ‘Niedersachsenbrücke’; that is, the jetty built for the Alusuisse project. As the aluminium industry was suffering from a severe drop in sales since early 1973, the project was halted and the jetty left more or less out of use. In a critical letter to the editor, a member of a recently formed local party closely tied to the environmentalist groupFootnote 43 sneered about the ‘romantic silence of the Niedersachsenbrücke …, disturbed only twice a month by a salt ship from the Netherlands’.Footnote 44 Roscher, however, did not discuss the economic shortcomings of the Alusuisse project, but suggested using the oil crisis as an argument for Wilhelmshaven. The crisis, he argued, demonstrated that the economy was too dependent on the oil-producing countries’ ‘mood’. Since their behaviour could find ‘imitators’, a ‘timely safeguard against supply disruptions’ was necessary. This, he concluded following broader economic trends towards diversification, could be Wilhelmshaven's chance as a potential national provisioning centre for natural resources.Footnote 45

The crisis not only served as an argumentative base for considerations about future developments, but also as a backdrop for validating past decisions and investments. In his speech at the festive setting of the refinery's foundation stone in May 1974, Mobil Oil's German CEO Herbert C. Levinsky explained that the oil crisis had not upset his or the company's belief in the validity of their decision. To him, building the refinery in Wilhelmshaven was as reasonable now as it had been in 1972. The oil crisis, he summarized, ‘has made the tasks we are facing here – contributing to energy supply and attracting further business – even clearer to us’.Footnote 46

The NWO was not worried about the oil crisis either but even considered it as a legitimation of their efforts. When a further dredging of the waterway was finished in April 1974, Horst Apel, the NWO's director, declared that his company had been correct in demanding that the ‘Federal Republic needed to become at least partially independent of foreign import harbours and refinery sites’. The oil crisis did not just prove this point, he continued, but also Wilhelmshaven's importance for the German refineries. ‘Thanks to the expansions [supported by the NWO], the oil port was capable to remedy the shortages several refineries faced due to the embargo on Rotterdam.’Footnote 47 In January, Heinz Gerken, economic correspondent of the WZ, had already reasoned similarly. The NWO and Lower Saxony had invested more than ‘1bn in developing Wilhelmshaven into the German oil base, to become at least a little independent from Marseille and Rotterdam. These times of crisis confirm that the investments were economically profitable.’Footnote 48 These judgments were in keeping with the position of the administration, which Eickmeier had formulated very early on. In an interview with the WZ, he explained in early November 1973 that ‘this situation of crisis vividly demonstrates the necessity of developing the German deep water harbour here’.Footnote 49

It would be too simplistic to understand the oil crisis in the almost omnipresent formula of ‘crisis as opportunity’. Looking at the contemporary assessment of the oil crisis, there certainly was a decidedly anticipatory and optimistic dimension to it, which Roscher spelled out when he suggested using it as an argument. The perceptions of crisis contained the past as a temporal frame of reference, too. In this case, the crisis clearly validated past decisions and, hence, corroborated the local power relations: since the policy of industrialization was validated through the crisis, changing these policies must have seemed unreasonable.

Prelude II: optimistic futures and disenchanting presents

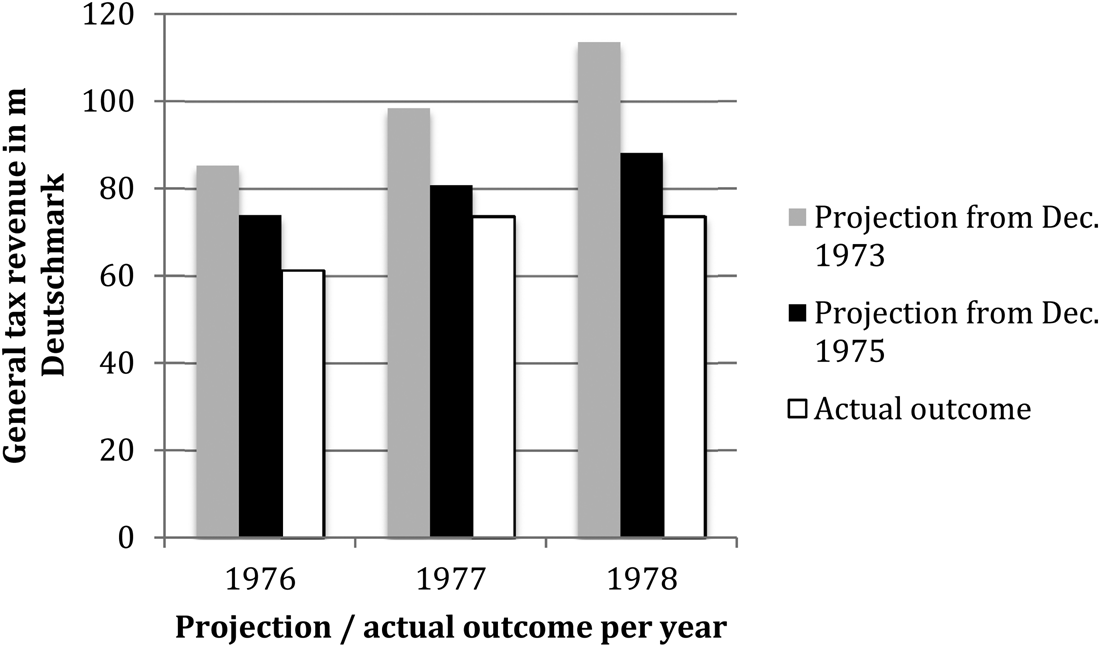

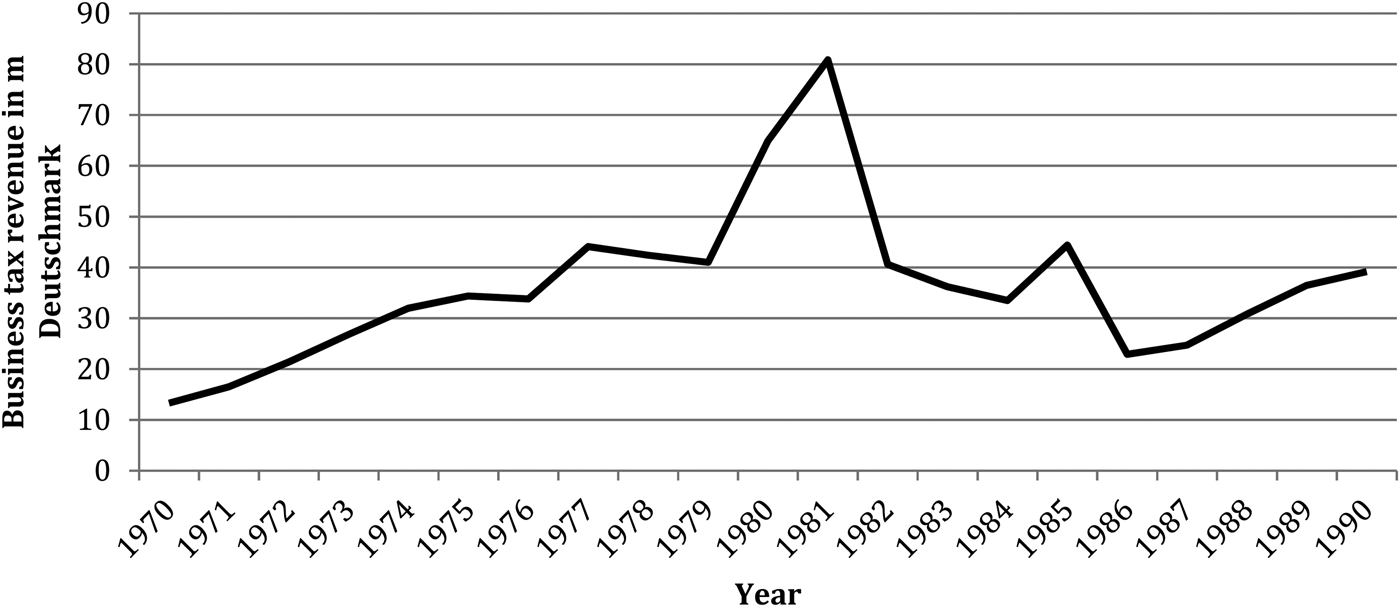

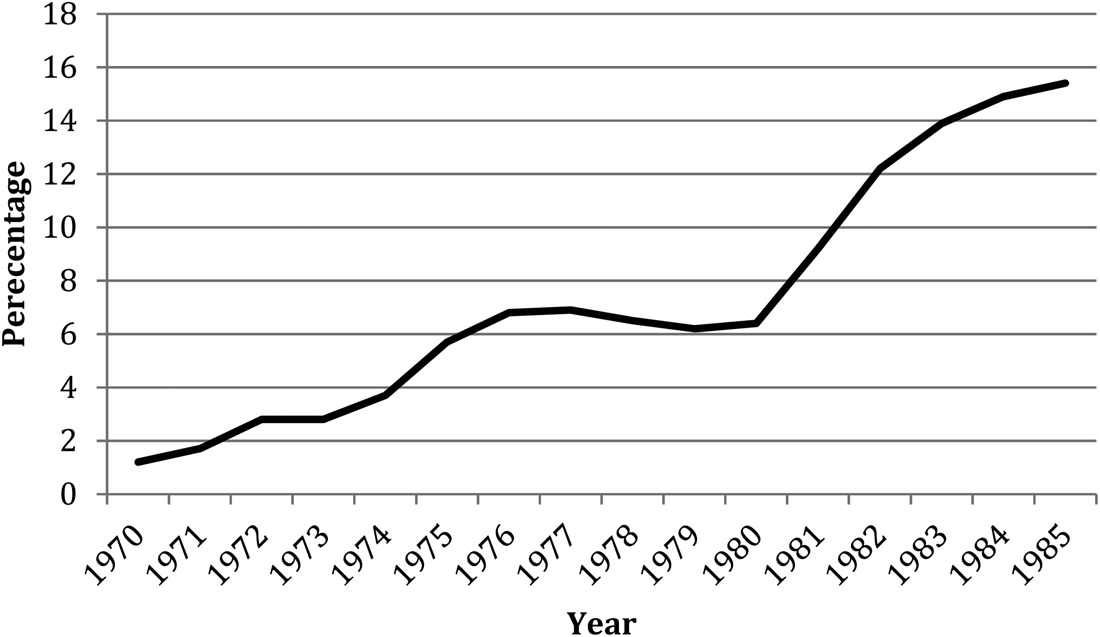

When the refinery was inaugurated in September 1976, Mobil Oil's vice executive president Curtis M. Klaerner recapitulated the developments of the past four years, in which ‘all of us have experienced the severe effects of opposing drifts in politics, economy, and currency’. These developments, he concluded, had an important learning effect for ‘the industrialized world … [, which] not only adapted to the situation but emerged stronger and more experienced than before’.Footnote 50 Klaerner's speech is representative of the general atmosphere in mid-1970s Wilhelmshaven, where an optimistic outlook at the future frequently met a disenchanting present. A prime example of this peculiar mixture can be found in the considerable discrepancies of the city's budget projections from 1974/75 and 1976/77 (Figures 1 and 2). Both the business tax and the overall tax revenue projections indicate a decreasing, but still prevailingly optimistic view of the future. As the third columns indicate, none of these projections ever came close to the real outcome. It even began to drop between 1977 and 1978. With two exceptions in 1980 and 1981, which are due to tax reforms on the national level, this trend remained constant until 1990 (Figure 3). City council and administration reacted to these trends, too. The disenchanting present becomes almost palpable in an unprecedentedly gloomy note for New Year's Eve in 1976. Here, the new mayor, Eberhard Krell, and Eickmeier told their readers that ‘everybody has their own problems’ and that this is not the time ‘for emotional words’ about the past year.Footnote 51 A year before, Krell's predecessor Arthur Grunewald and Eickmeier had not been so taciturn about the city's problems. ‘The past months brought bitter disappointments, as the general recession hit Wilhelmshaven, too, and increased the citizens’ unemployment.’Footnote 52 Indeed, the unemployment rates had been rising almost continuously since 1970 (Figure 4). One segment affected by job losses was the construction business. Even though this was a general trend in 1970s Germany, the job losses in Wilhelmshaven are particularly striking, because the refinery and a coal power station were huge construction sites. Combined, both sites attracted more than 3,000 construction workers, of whom, however, fewer than 500 came from Wilhelmshaven or nearby regions.Footnote 53

Figure 1. Business tax revenue projections and outcome

Figure 2. General tax revenue projections and outcome

Figure 3. Business tax revenue (long term)

Figure 4. Unemployment rate (long term)

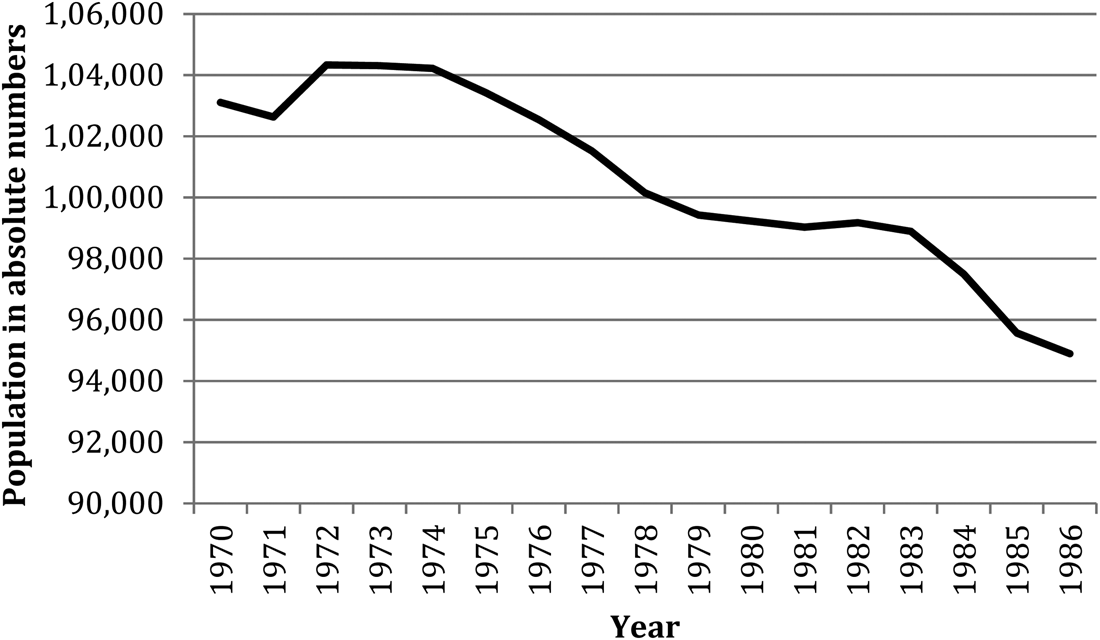

Industrial workers also severely suffered from job losses.Footnote 54 The loss of industrial jobs was in keeping with general trends in Germany, where a segregated labour market evolved that could not absorb a workforce trained for industrial labour.Footnote 55 An internal report of the planning department indicated a direct connection between the loss of industrial jobs and the slow but steady decline of Wilhelmshaven's population (Figure 5). Emigration beyond city limits, the report from 1980 found, was ‘clearly characterized by jobs from the producing sector’.Footnote 56 Interestingly, the larger proportion of jobs – roughly 1,400 – in the industrial sector was lost between 1970 and 1975; that is, the time largely marked by optimism and euphoria about the successful attraction of Alusuisse and Mobil Oil. In comparison, between 1975 and 1980, ‘only’ approximately 400 further jobs were lost here.Footnote 57 This incongruity suggests that the aforementioned patterns of optimism and validation that had developed since April 1970 then concealed the problematic structural developments.

Figure 5. Population in absolute numbers

Yet, the bleak present neither tarnished the belief in future prospects nor – and this is more important – the politics of attracting capital-intensive industries, even though their anticipated pull-effects for labour-intensive industries came to nothing. In his speech about the budget plan for 1976, the treasurer spelled out the almost eschatologicalFootnote 58 dimension of the authorities’ belief in the future. Although ‘the current situation of our finances and of our budget poses a challenge’, the authorities should not be ‘discouraged by the dictate of the empty coffer’. He called on the council members ‘to contribute to an improvement of the general atmosphere – from pessimism towards faith and confidence!’Footnote 59 This, he explained, was in keeping with the suggestions of the National Council of Economic Experts.

Representative brochures and notes on the New Year, published on New Year's Eve, became the medial habitat for the city's optimism. Despite the anxiety about the oil crisis, Eickmeier and Grunewald explained by the end of 1974 that the city had made a ‘step forward’.Footnote 60 A year later, a journalist of the WZ claimed that the city ‘consolidated itself as a seat of industry in the past year’ and would continue to thrive in the upcoming ‘year of destiny and regional elections’.Footnote 61 The representative texts were, of course, even more outspoken about Wilhelmshaven's opportunities. In a promotional journal from 1976, where any city could represent itself, Wilhelmshaven boasted with ‘41,000 crisis-proof jobs’.Footnote 62 Brochures from 1975 and 1978 propagated the slogan of a ‘young city full of opportunity’,Footnote 63 another brochure took up maritime tropes and spoke of ‘economic upwinds’,Footnote 64 and the local savings bank proudly declared in 1979 that Wilhelmshaven had ‘every chance for the future’.Footnote 65

Since the beginning of Wilhelmshaven's ‘breakthrough’ in 1970, Lower Saxon politicians also encouraged the city's belief in a prosperous future – if the attraction of industries continued. In May 1974, Lower Saxony's secretary of commerce, Helmuth Greulich, declared his ‘optimism about the future development: there is a strong interest in Wilhelmshaven and Mobil Oil's foundation stone will certainly not be the last to be laid here’.Footnote 66 When the contract with the liquid gas terminal was signed in 1976, Greulich's predecessor, Walther Leisler Kiep, took almost the same line. He knew of no fewer than eight companies interested in settling in Wilhelmshaven, a regional newspaper from the nearby city of Jever reported.Footnote 67 Again, the liquid gas terminal as well as the coal power station and the refinery, which were opened a few months later, were praised for their contributions to the city's tax revenues and their potential pull-effects for labour-intensive industries.Footnote 68 The conviction of potential pull-effects becomes almost tangible in a headline from February 1977, when Mobil Oil's plans to build a crackerFootnote 69 transpired: ‘An initial spark for further industrial settlements can be expected from the Mobil Oil Refinery.’Footnote 70

Even though the plants themselves created a meagre 500 jobs, the Social Democrats, then governing the city, promised to ‘continue the ongoing politics of attracting industry’Footnote 71 in their programme for the 1978 Lower Saxon elections – and they did. Shortly before the elections, an option contract about building a PVC production site was signed with the British ICI – despite the ecological uncertainty of the projectFootnote 72 and the company's questionable closure of its Offenbach plant in 1978. When the plant opened in 1981, the company sent image brochures to the citizens, explaining that ‘Wilhelmshaven needs an active economic life’ to which the ICI would contribute. They praised the ‘consequent and well-measured economic policy’ and promised to contribute to the city's further prosperity, modernity and success in the future.Footnote 73

‘The most difficult situation since the end of World War II’ – the end of industrialization

In its issue for New Year's Eve 1979, the WZ took a proud look back at the decade in which ‘Wilhelmshaven established itself as a seat of industry.’ The journalist had spoken to local politicians, who ‘characterized the industrial settlements … as one of the most important events of the fading decade’.Footnote 74 In 1985, only six years later, the situation was assessed completely differently. The new chief-municipal director Arno Schreiber diagnosed an ‘eminently difficult situation, maybe the most difficult situation since the end of World War II’.Footnote 75 These diametrically different assessments about Wilhelmshaven's situation mark the beginning and the end of a phase in which various problems escalated in fairly rapid succession.

Wilhelmshaven's changing slogans illustrate this process. The ‘young city full of opportunity’,Footnote 76 which was a motto throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, became ‘the likeable city at the ocean’Footnote 77 by 1984 – and this likeable city faced severe economic problems, whose inception can be detected in Eickmeier's comment about the new challenges the city would have to cope with in the 1980s. In an outlook of the next decade, he said, ‘we will need labour-intensive plants as satellites around the Voslapper Groden at any cost’.Footnote 78 Apparently, administration and politics had realized that the declining population and the problems of the labour market were due to the lack of labour-intensive industries. But these industries did not come. Instead, the city intended to attract a coal-gasification complex by the Shell company. When the ‘second oil crisis’ was over and the petrol price began to drop to its pre-crisis level, Shell quickly discontinued the project in 1983. The coal-gasification complex would prove to be the last large-scale industrial project.Footnote 79 The liquid gas terminal also never made it beyond the project stage and in 1985 the refinery closed its doors for good. Between these severe setbacks for the city's industrialization strategy, Eickmeier resigned in 1984 amidst allegations of bribery.Footnote 80

Historian Thomas Mergel characterizes crises as ‘times of rapid change’.Footnote 81 Even though this is a broad-brush characterization, it is certainly accurate for the phase between 1983 and 1985. Furthermore, contemporaries began to use the term as a means to describe Wilhelmshaven's situation for the first time since the early 1950s. At the Social Democrats’ district congress in May 1984, where the negative spiral of events – from the scandal evolving around Eickmeier through to the economic and social problems – created quite a stir, the district party leader, Udo Bergner, cautioned against social hardships in the ‘solution of this crisis’. To him, ‘this crisis’ was composed of the ‘crash of business tax revenue … and the simultaneous increase of benefit expenditure’.Footnote 82 A year later, the party's regional candidate for the general elections, Wilfried Adam, added ‘the shutdown of Mobil Oil, the rapid increase of social costs, high unemployment, and so on’.Footnote 83 In the mid-term urban development plan that Schreiber commissioned immediately after taking over from Eickmeier, he spoke of crisis, too. After detailing the dramatic budgetary situation, for which he held the ‘investment decisions of the 1970s’Footnote 84 responsible, he declared: ‘Now, we do not need the encompassing “fine weather” planning based on safe growth rates, but an instrument to detect and overcome crisis-ridden developments and to reorient in difficult times.’Footnote 85 In order to overcome ‘the barriers for further development’,Footnote 86 he suggested to put emphasis on supporting local and medium-sized business. Effectively, this meant the end ‘of the long-term fixation on large-scale industrial complexes’.Footnote 87

Conclusion

For the greater part of the 1970s, media, politicians, corporations and administration drew a positive and optimistic picture about Wilhelmshaven's present and, in particular, its future. This optimism was closely connected to the attraction of specific industries, specifically large-scale extractive complexes from the petrochemical industry. Yet it also belied the problematic developments of the city's finances and on the labour market. Furthermore, the initial successes of attracting Alusuisse and Mobil Oil glossed over the failure of attracting further plants let alone labour-intensive industries. Hence, the more encompassing and general historiographical findings about Germany in the 1970s are both borne out and called into question by local developments in Wilhelmshaven.

Wilhelmshaven was in keeping with the general trend of a declining industrial labour market. Yet, this did not correspond with a decline in industrial investment. The city rather saw a surge of huge construction activity for industrial complexes. This raises the question of the nature of Wilhelmshaven's industrialization. In its self-description and in the context of planning, Wilhelmshaven surely was an industrializing city. Moreover, industrialization was more than just plans on paper. Concrete steps were taken: plants were built and industrial areas had their infrastructure developed. In addition, there was opposition to the attraction of extractive industries, their ensuing ecological problems and their irrelevance to the labour market. If Wilhelmshaven had not been an industrializing city, such protest would have been neither necessary nor plausible. These findings provoke further research into the history of (sea) port cities and their politics of industrialization. At least for Antwerp, Rotterdam and Hamburg, a growing interest in the petrochemical sector can be observed, too.Footnote 88 Especially because of their varying degrees of success, a comparative look at these politics seems to be a promising field of research on (sea) port cities.

Next to these findings about the city's industrialization, the Wilhelmshaven case contradicts well-established narratives about the 1970s in Germany. In Wilhelmshaven, the 1970s were not the tipping point from optimism to pessimism. None of the ‘common suspects’; that is, the collapse of the Bretton Woods currency system, the first oil crisis, or the ensuing recession, impaired the general atmosphere of hope and optimism. Only after the acceleration of problematic developments in the first half of the 1980s did administration and politics put a stop to further industrialization. This ties in with Frank Bösch's recent suggestion that 1979 was the significantly more important date when it comes to a history of our present.Footnote 89

These findings are suggestive for at least three perspectives on the concept of crisis in urban history. First, the analysis of the first oil crisis has shown that historiographical diagnoses about it being a watershed are subverted by local developments. Studying global diagnoses in a local context is not only a benefit of urban history but also a necessary prerequisite when investigating crises. Secondly, a closer look at crises in cities beyond tropes such as ‘urban crisis’, or rise and fall narratives, seems promising. Even though the characterization of crises as ‘times of rapid change’Footnote 90 is not a sufficient definition, it is illuminating to take a closer look at precisely such phases of acceleration, when past and present developments collide and create a constellation generally referred to as ‘crisis‘, i.e. a phase of latency when a city's weal and woe are at stake. Both crises, thirdly, had decidedly temporal dimensions. While the first oil crisis served as an argumentative framework for validating past decisions, fostered the belief in future progress and sharpened the perspective on the present, the mid-1980s saw a collision of the past with the present, in which a severe change of the city's economic policy was deemed necessary for the future.