Pre-law advising and the discipline of political science share a long history. As early as 1968, the APSA offered advice to pre-law advisors in PS: Political Science & Politics, its journal of record. The APSA Annual Meeting regularly includes short courses devoted to pre-law advising, and job openings in political science—particularly in the American politics and public law subfields—often include pre-law advising as a requirement for the position. Despite this long-standing association, little is known about the relationship between pre-law advising and the discipline of political science.

Although the American Bar Association (ABA) “does not recommend any undergraduate majors or group of courses to prepare for a legal education” (American Bar Association 2015), political science often is seen as an appropriate course of study for those interested in law school. Astin (Reference Astin1984) found that the political science major was frequently selected by freshmen who indicated that they planned to be an attorney and earn a law degree. Among those students, political science was the most popular major (31.7%), followed by pre-law (15.5%), business administration (7.8%), history (5.3%), and accounting (4.5%). According to recent data from the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), 18% of law school applicants were political science majors; the next three most popular majors (i.e., psychology, English, and history) were much less popular, each with rates of approximately 5% (Law School Admission Council 2015). However, it is not known if these same majors are those recommended by pre-law advisors and we do not have a sense of what pre-law advisors think about the political science major as a pre-law course of study.

As one might expect, there has been normative work about the best majors for law school. For example, Kelley (1960, 1184)—who cautioned against the traditional paths of political science or business when preparing for law school—wrote that:

Although general knowledge of the structure of state and national governments and the subtleties of double-entry booking are undoubtedly important to every lawyer and crucial to some, the prospective law student should devote a generous portion of his time to the study of cultural heritage; he should attempt at least a nodding acquaintance with modern science; he should become actually aware of the distinctions between statements of fact and value; he should know when the line has been crossed between the discussion of an idea and the propagation of an ideology.

We found one empirical study in which practicing attorneys and judges rated the top five majors for law school. According to this research, they ranked business, political science, economics, English, and philosophy as the best preparation (Martellaro Reference Martellaro1984).

In addition, LSAC data reveal that students who major in political science are successful at gaining admission to law school. Although they tend to have LSAT scores that are somewhat lower than those who pursue other majors, the admission rate for political science majors is fairly high, exceeding 80% in recent years (Law School Admission Council 2015). Given its popularity as a major and the extent to which it may enhance students’ chances for admission to law school, examining the nature of pre-law advising and the views of pre-law advisors on political science is an important addition to our understanding of the discipline and how political science can better serve pre-law students and their institutions.

In addition to discussions about different courses of study pursued by those interested in law school, the literature raises questions about the use of faculty or staff resources for pre-law advising. Political scientist Rebecca Gill investigated 16 peer institutions and found that 11 schools had professional staff and five employed faculty or instructors as pre-law advisors (Haynie Reference Haynie2014); however, it is not known whether this finding would hold up nationally.

Likewise, nothing is known about the educational background of pre-law advisors. Does the typical pre-law advisor have a PhD, a JD, both, or neither? In an effort to learn about the qualifications and preparation of these advisors, our survey included questions about their educational background.

Given the substantial changes taking place in legal education in the United States, we believe that this is a particularly appropriate time to investigate pre-law advising. Law school enrollment numbers continue to decline and the cost of attendance remains high (Olson and Segal Reference Olson and Segal2014). The price tag for a legal education is particularly problematic, given the challenges of gaining employment after graduation (Tamanaha Reference Tamanaha2012). Some law schools, confronted with smaller applicant pools, have even begun to admit more and potentially less qualified students (Rivard Reference Rivard2015).

This article offers an initial look at these issues by presenting the results of a survey of pre-law advisors at US colleges and universities. Our questions addressed a range of topics, focusing particularly on the presence and extent of pre-law curricula and the perspectives of pre-law advisors on political science as preparation for admission to and success in law school. We also compared the opinions of pre-law advisors about political science with other popular undergraduate majors. It is our hope that political science departments, pre-law programs, and university administrators can use these findings to assess their own programs and to develop strategies for improvement.

DATA AND METHODS

We conducted a web-based survey of pre-law advisors in February 2015. We sent surveys to all pre-law advisors listed in the Fall 2014 LSAC Directory. The directory included two categories of pre-law advisors: “sole/coordinating” advisors and “supporting” advisors. Because we wanted to focus on the primary advisor at each institution, we sent our survey to sole/coordinating advisors only. Our final mailing list included 1,396 valid e-mail addresses. In addition, each person on the list had one of six regional affiliations with the Pre-Law Advisors National Council: 20% from the Midwest Association, 31% from the Northeast Association, 10% from the Pacific Coast Association, 21% from the Southern Association, 12% from the Southwest Association, and 6% from the Western Association. We received 313 completions, for an overall response rate of 22%. Fortunately, the regional affiliations of our respondents matched well with our population: 19% from the Midwest region, 28% from the Northeast region, 11% from the Pacific Coast region, 20% from the Southern region, 13% from the Southwest region, and 9% from the Western region. We sent an initial e-mail on February 4, 2015, and two reminder e-mails requesting completion of the survey, which included 26 questions.

One of the first questions the survey asked was whether advisors were classified as faculty or staff at their college or university. We discovered that 76% of respondents identified as faculty and 24% identified as staff.

FINDINGS

One of the first questions the survey asked was whether advisors were classified as faculty or staff at their college or university. We discovered that 76% of respondents identified as faculty and 24% identified as staff. As one might expect, these percentages differed considerably across the type of institution. Using three Carnegie classifications (i.e., bachelors, masters, and doctoral), we found that 73% of advisors from bachelors institutions, 92% from masters institutions, and only 55% from doctoral institutions were faculty. Our findings are similar to previous research, reporting that 69% of schools utilized staff and 31% relied on faculty (Haynie Reference Haynie2014). We also note that pre-law advisors held a variety of faculty titles, including adjunct professor, lecturer, assistant professor, associate professor, professor, department chair, associate dean, and even dean. Staff titles included academic advisor, coordinator, and director. Our survey also was completed by a university librarian and a university general counsel.

We asked pre-law advisors how long they had worked in their current position. As one might expect, there was considerable range in the amount of experience, from only a few months to one respondent who reported serving as a pre-law advisor for 50 years. Overall, we discovered that pre-law advisors have considerable experience, serving an average of 12.4 years in the position. We also found that there was a statistically significant difference (i.e., p<0.05) between the years of experience for faculty and staff. Faculty served in the position for an average of 13.2 years, whereas staff served for an average of 9.6 years. There were no notable differences in the amount of time that a pre-law advisor had served across institutional type.

We also wanted to study the educational background of pre-law advisors. Given the high percentage of faculty serving as pre-law advisors, it is not surprising that 58% of respondents hold a PhD. As mentioned previously, bachelors and masters institutions were more likely to have faculty serving as pre-law advisors than doctoral institutions. Therefore, it was not particularly surprising that there was a higher percentage of pre-law advisors with a PhD at bachelors- and masters-level schools than at doctoral-granting institutions. We also asked how many pre-law advisors had law degrees and discovered that 43% had a JD. Doctoral institutions had a slightly higher percentage of JD pre-law advisors than masters and bachelors institutions. In addition, we found that 19% of pre-law advisors indicated that they had both a PhD and a JD. Last, we found that 18% of respondents indicated that they had neither a PhD nor a JD.

We discovered that almost all pre-law advisors work without monetary compensation. According to the survey results, 93% of the respondents indicated that they did not receive any additional compensation for serving as a pre-law advisor. Of those who reported additional compensation, the amount ranged from $100 to $25,000, with an average of approximately $5,400. Stipend amounts were substantially higher at masters and doctoral institutions than they were at bachelors institutions.

The results were similar regarding course-release time. We asked respondents who were also faculty whether they received any course releases for serving as pre-law advisor, and we were surprised to learn that 81% of respondents did not. Only 13% reported receiving a one-course release and only 5% reported being released from two or more courses in the academic year. Several respondents commented on the lack of course releases as a particularly challenging aspect of their job. As one might expect, the amount of course-release time was greater for pre-law advisors at doctoral-granting institutions than at masters and bachelors schools.

Our survey also included several questions about additional resources available to pre-law advisors. We found that only 19% of respondents had a separate budget for pre-law advising. Among those who indicated a separate budget, the amount ranged from $100 to $75,000, with an average of approximately $7,300. We were surprised to find that 29% of pre-law advisors at bachelors-only schools had a separate budget, compared to 13% at masters schools and 25% at doctoral-granting institutions.

We also asked about the availability of Law School Admission Test (LSAT) preparation courses on the respondents’ campuses. We found that 31% of advisors indicated that their school offered LSAT preparation and 69% indicated that their school did not. Several respondents mentioned that they provided informal assistance with the LSAT as part of their advising duties, such as sponsoring LSAT workshops and offering mock LSAT testing. Last, the likelihood of LSAT preparation did not differ significantly by institutional type.

Given the national news about the decline of law school applications and the difficult job market facing law school graduates, we were interested in how pre-law advisors would rate the job prospects for today’s graduates. The results from this question, shown in figure 1, indicate that slightly more than 50% of pre-law advisors rated job prospects for law school graduates as either “Poor” or “Fair.” In fact, the modal rating category was “Fair,” at 42%. The other half of respondents were slightly more positive about job prospects for today’s law school graduates: 37% rated them as “Good” and 10% as “Very Good.” Only 3% of respondents rated job prospects as “Excellent.”

Figure 1 Pre-Law Advisors’ Rating of Job Prospects for Law School Graduates

We also investigated the presence of specific pre-law programs at colleges and universities. We asked pre-law advisors whether there was a pre-law major, a pre-law minor, or a pre-law concentration at their institution. As shown in figure 2, a pre-law concentration was the most common type of program, with 33% of respondents indicating its presence. A pre-law minor was also a fairly common occurrence, with 28% of pre-law advisors reporting a concentration. Pre-law majors, however, were rare, with only 6% of respondents indicating that it was possible to major in pre-law at their institution. It is interesting that whereas one respondent expressed a strong desire to have “a more formal pre-law curricular option,” that same respondent also stated that “students can do a great job in law school and as lawyers without the curricular offering.” Another respondent commented that the ABA and the LSAC both recommend against students pursuing a pre-law major, advice that—given the dearth of pre-law majors—institutions seem to be following. There were not many differences in the number of pre-law majors, minors, and concentrations among institutional types. We discovered that a slightly higher percentage of masters institutions had a pre-law concentration (i.e., 41%), compared to only 30% at both doctoral-granting and bachelors institutions.

Figure 2 The Presence of Pre-Law Majors, Minors, and Concentrations on Campuses

We then asked pre-law advisors for feedback on 14 common majors for students planning to attend law school. We asked them to rate each major in terms of how well it prepares students for admission to and academic success in law school. We decided to include these two questions in our survey because we believed that gaining admission to law school and being a successful law student do not necessarily require the same skills or attributes. We asked pre-law advisors to rate majors in general rather than a particular program at their institution. We instructed respondents to leave the question blank if they were not able to provide a rating.

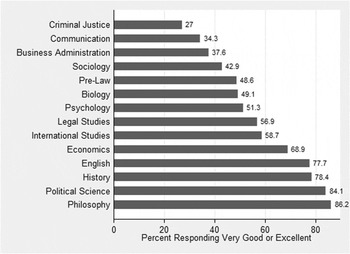

Figure 3 shows the ratings of majors in terms of how well they were rated as preparation for admission to law school. The solid bars represent the percentage of respondents who rated the major as “Very Good” or “Excellent.” As shown in figure 3, pre-law advisors rated political science as the second-best major in terms of preparation for law school, slightly behind philosophy. The traditional liberal-arts majors of history, English, and economics were also rated fairly highly, ranking third, fourth, and fifth, respectively. In the open-ended section of the survey, respondents also specifically mentioned “hard sciences like engineering” and even physics as helpful majors.

Figure 3 Pre-Law Advisors’ Ratings of How Well a Major Prepares Students for Admission to Law School

International studies, an interdisciplinary major that political science department chairs rate as less academically rigorous than political science (Knotts and Schiff Reference Knotts and Schiff2015), appeared in the middle. We were surprised to find that sociology and psychology, two other traditional liberal-arts majors popular among pre-law students, did not receive higher ratings from pre-law advisors. It also was interesting to note that the three majors with close connections to the study of law (i.e., legal studies, pre-law, and criminal justice) were rated less well by pre-law advisors, with criminal justice ranking in last place. Whether right or wrong, criminal justice programs are known more for providing job training for law-enforcement personnel than for preparation for law school.

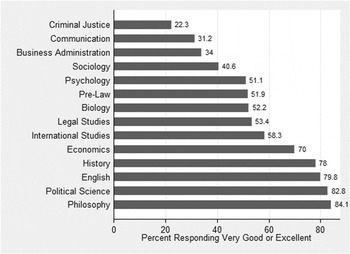

There appears to be little difference in pre-law advisors’ sense of the best undergraduate majors for admission to versus performance in law school.

Figure 4 presents results from the survey question about how well particular majors prepare students for academic success while in law school. The results illustrated in figure 4 are similar to those in figure 3. Philosophy and political science are again rated the highest by pre-law advisors, whereas communication and criminal justice are again rated the lowest. The only notable difference between the results presented in figures 3 and 4 was that English and history reversed places in the ranking. There appears to be little difference in pre-law advisors’ sense of the best undergraduate majors for admission to versus performance in law school.

Figure 4 Pre-Law Advisors’ Ratings of How Well a Major Prepares Students for Academic Success in Law School

We began by investigating the differences between the ways that JD and non-JD advisors rated political science. We found that 81% with a JD rated political science as “Very Good” or “Excellent” preparation for admission to law school, compared to 87% of those without a JD. Likewise, 79% of advisors with a JD rated political science as “Very Good” or “Excellent” preparation for academic success while in law school, compared to 87% of non-JD advisors.

We also explored differences in the ways that faculty versus staff rated political science. We found that 85% of faculty rated political science as “Very Good” or “Excellent” preparation for admission to law school, compared to 81% of staff. In terms of rating political science as preparation for academic success in law school, 85% of faculty rated the major as “Very Good” or “Excellent,” compared to 78% of staff.

Next, we used a regression model to predict the rating of the political science major in terms of preparation for admission to and performance in law school. Given the categorical dependent variables, we used an ordinal logit model. We included six independent variables: whether the pre-law advisor was faculty or staff, the number of years the pre-law advisor has served in the position, whether the pre-law advisor has a JD, whether the advisor was a political scientist, the Carnegie classification for the advisor’s school, and the average SAT score at the respondent’s institution. Footnote 1 Last, to more easily interpret our results, we report some predicted probabilities for the significant independent variables.

The results of our model are in table 1. As shown in the table, whether pre-law advisors self-classified as faculty or staff was not a significant predictor of how they rated the political science major. The average SAT score at advisors’ institutions also does not affect their ratings of political science. These two results were consistent across both of our dependent variables. The results for the Carnegie variable (i.e., bachelors = 1, masters = 2, and doctoral = 3) indicate that advisors at higher Carnegie-classification schools rated the major less favorably than those at lower Carnegie-classification schools—but only for admission to law school. There was no difference among the advisors at different types of institutions about how well political science prepares students for academic success in law school.

Table 1 Rating the Political Science Major for Admission to and Success in Law School

Note: Entries are ordinal logit regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0 .10; **p < 0 .05; ***p < 0 .01(two-tailed test).

Regarding advisors’ own backgrounds, those who were political scientists were more likely to rate political science more positively, across both dependent variables. Having a JD did not affect a pre-law advisor’s rating of political science in terms of admission to law school, but it affected the second dependent variable. A pre-law advisor with a JD was significantly more likely to rate political science less positively for success in law school. Footnote 2

In addition, years on the job had a positive and significant effect on the rating of the political science major—again across both dependent variables. A pre-law advisor with more years in the position was more likely to rate political science more positively, in terms of both admission to and success in law school, even after controlling for the advisor’s own background in political science. Footnote 3

In terms of substantive effects, the predicted probabilities show that having more experience as a pre-law advisor has a significant effect on the evaluation of the political science major. As the variable capturing the number of years serving as pre-law advisor increases from its minimum to its maximum, the probability of rating political science as an “Excellent” major for admission to law school increases from 32% to 61%—an increase of 29 percentage points. As for whether the major is “Excellent” preparation for performance in law school, the increase is even larger, at approximately 37 percentage points. Footnote 4 It appears, therefore, that those who have been a pre-law advisor longer are more inclined to view political science as more helpful for admission to law school than those with less experience. They also are much more likely than those with less experience to view it as helpful for academic success in law school.

The type of institution has a moderate substantive effect. Advisors who work at doctoral-granting institutions are 14% less likely to rate political science as “Excellent” preparation for admission to law school than those who work at bachelors institutions and 7% less likely to do so than those who work at masters institutions. Footnote 5

If a pre-law advisor is also a political scientist, this increases the ratings of political science—but perhaps not by as much as one might expect. If advisors are political scientists, they are 15% more likely to rate the discipline as “Excellent” preparation for admission to law school and 14% more likely to rate it as “Excellent” preparation for performance in law school than those who are not political scientists. Political scientists are more favorable toward their own discipline, but the effect is not overwhelming. The time spent as an advisor appears to have a greater effect.

However, we discovered differences among different categories of pre-law advisors. Those with a JD rate political science less favorably than non-JDs—at least in terms of helping students perform well in law school. As mentioned by several respondents, this may reflect their sense that skills are more important than content for academic success in law school—skills that other majors also may provide.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Given the strong connection between political science and law school and the dearth of knowledge about what pre-law advisors think about the discipline, our study provides new information that political scientists should find helpful as they guide students interested in pursuing a legal education. In addition, our results provide political scientists an opportunity to see how their approach compares with other schools and to consider how the discipline as a whole might better prepare students for law school.

Our findings indicate that the majority of pre-law advisors are faculty members, that they operate without a separate budget, and that few receive course releases or additional compensation for their pre-law advisory duties. We also found that pre-law advisors are favorable toward a major in political science regarding both admission to and academic success in law school. Indeed, only a philosophy major was evaluated more highly.

However, we discovered differences among different categories of pre-law advisors. Those with a JD rate political science less favorably than non-JDs—at least in terms of helping students perform well in law school. As mentioned by several respondents, this may reflect their sense that skills are more important than content for academic success in law school—skills that other majors also may provide.

It is not surprising that advisors who were political scientists were more likely to evaluate political science positively. Nevertheless, marked differences were observed between longer- and shorter-serving pre-law advisors. Longer-serving advisors feel particularly positive about a political science major; indeed, as pre-law advising experience increases, the probability of deeming political science as “Excellent” as preparation for both admission to and academic success in law school increases substantially. Presuming that more experience as a pre-law advisor generates a better understanding of law school admissions and the rigors of law school, political scientists should know that their discipline remains a well-regarded major for those interested in a legal education.

We hope that future research will look beyond specific majors and focus on the ways that certain classes prepare students for law school. As Grigsby and Murphy (Reference Grigsby, Murphy, Garrison and Guliuzza2012) discovered, admission to law school may be more closely related to a student’s ability to complete coursework rather than enrollment in a particular political science class. Several respondents also suggested that academic skills are more important than particular courses. One respondent stated that “law school is skills based…[and] a student can get those skills in any major.” Another specifically mentioned using advising time “persuading students that law-related [course] content is far less important than law school skills development.” Future research might consider surveying law school admissions directors and/or law school faculty to determine the specific skills that are useful for success in law school, as well as evaluating whether and how political science departments can provide those skills.