There is a very important conundrum inextricably embedded in the democratic conception of the “will of the people.” This conundrum involves an “opening dilemma” that makes it impossible to create a constitutional assembly without relying on arbitrary decisions as to who will participate and how they will deliberate.Footnote 1 As a result, a democracy cannot found itself because the will of the people cannot, in the absence of unauthorized intervention, create an institutional form through which the people can rule themselves. Political theorists have primarily focused on the abstract problem of democratic legitimacy that attends the failure of a people to authorize themselves as a political collective. This study extends that discussion in several ways.

As political theorists have often noted, it is impossible for people to democratically decide that they constitute a “people.” This inability seriously, if not fatally, undermines their collective right to make democratic decisions that can bind those who dissent. Seyla Benhabib, for example, concludes that “we face a paradox internal to democracies, namely that democracies cannot choose the boundaries of their own membership democratically.”Footnote 2 Jason Frank notes that that Rousseau's invocation of the Lawgiver as a solution “actually models fundamental dilemmas of authorization that necessarily haunt the theory and practice of democratic politics.”Footnote 3 And, as Howard Schweber observes, this dilemma of democratic authorization involves “a basic political principle that those actors [who create a democratic state] are agents who represent (with all the myriad variations of that concept) the sole authorizing agent, the people.”Footnote 4

Bonnie Honig has described the theoretical angst that results from this impossibility as “democratic theory's uncomfortable yet unavoidable dependence on the unreliable even phantom agency of the ‘people’ who may be called into being when called on in democratic politics.” Working through the sometimes complicated analytical acrobatics of theorists such as Seyla Benhabib and Jurgen Habermas, Honig concludes that the “paradox of founding” is that “the people do not yet exist as a people,” and thus “neither does a general will. The solution cannot be the right procedure or standpoint, for the people are in the untenable position of seeking to generate, as an outcome of their actions, the very general will that is supposed to motivate them into action.”Footnote 5

For his part, Habermas notes that “the constitutional assembly cannot itself vouch for the legitimacy of the rules according to which it was constituted.”Footnote 6 He then contends that the solution is to view politics as a continuously unfolding “founding” in which the democratic legitimation of a constitution is a never-ending work in progress. Honig, on the other hand, concludes that we must nonetheless “demand that the lawgiving/charlatan institutions by which we are always already governed and shaped be responsive to the plural, conflicting agents who together are said to authorize or benefit from them: the ever-changing and infinitely sequential people, the multitude, and their remnants.”Footnote 7 This, of course, simply shifts attention to the ongoing politics of a democratic society, a politics that owes its organization and design to the arbitrary decisions that enabled the founding of that society in the first place. In effect, this focus on the ongoing politics of a democratic society merely justifies itself through a circular logic while ignoring the profound theoretical implications of the opening dilemma. Among those implications is the fact that entire democratic project is founded on an unavoidable contradiction.

In extending this discussion, I do several things. First, I formally restate the problem and thus illustrate that it involves three interrelated elements: the identity of the people (and their authorized representatives); the adoption of rules of procedure that would transform their speech acts into meaningful legislative actions; and the selection of a presiding officer who would both recognize people to make such speech acts and interpret their relation to the rules of procedure. Second, I provide an empirical analysis of how these several elements all play a part in the creation of a constitutional convention (and, thus, in the democratic founding of a state). This analysis also demonstrates how the opening dilemma can involve a very real problem with no logical solution.

Third, I offer an explanation for why the opening dilemma rarely surfaces in the practical politics of constitutional conventions. However, the very fact that it is rarely manifested means that political actors are wholly unprepared for its consequences when it does appear. Finally, I briefly suggest that there the opening dilemma might actually threaten the survival of American democracy if the United States were to attempt to hold a new constitutional convention.

I will take these things up in that order, beginning with a formal statement of the opening dilemma, then proceeding to a close analysis of the proceedings of the Illinois Constitutional Convention in 1869 in which the opening dilemma presented a very serious problem, and concluding with some thoughts on the implications of the opening dilemma for both the theory and political practice of democratic states.Footnote 8

1. The Opening Dilemma

A basic principle of almost all democratic theories is that a constitutional convention embodies the will of the people through and by way of its decisions. For that principle to be realized in political practice, the will of the people must also direct and determine the creation of the convention. However, the convention itself is the only legitimate authority through which the will of the people can be expressed, and it has not yet itself been created. In order to resolve this opening dilemma, a democratic institution must simultaneously create itself while also determining who will constitute the “people,” who will represent them in the chamber, and how those representatives will make decisions. As many political theorists have noted, this is impossible in theory. In this article, I will demonstrate that it is also dangerous in practice.

Because the opening dilemma always attends the moment when a constitutional convention is created, it is theoretically unavoidable. However, the opening dilemma, once resolved, does not further complicate democratic decision making; it only appears during the creation of a democratic institution. Once a constitutional convention is created, the members are the sole judges of the qualifications of their colleagues, are solely responsible for the election of its presiding officer, and solely determine the procedural rules under which they deliberate. The political autonomy of a constitutional convention depends on these prerogatives and, in turn, its legitimacy as the embodiment of the will of the people depends on that autonomy. The problem involves the creation of that convention.

Three decisions must be made when such a constitutional convention is created: a presiding officer must be chosen, rules of procedure must be adopted, and the members must be recognized as the legitimate representatives of their constituencies. The opening dilemma arises from the fact that each of these decisions is a necessary precondition for the others (see Table 1). For example, a presiding officer cannot be chosen unless the members have been recognized as legitimate representatives of their constituencies and rules of procedure have been adopted. The presiding officer can only be chosen when these things have already been decided. In turn, rules of procedure cannot be adopted unless there is a presiding officer who can recognize (and thus authorize) a motion to that effect and the credentials of the members as agents of the people have been approved. Finally, the credentials of prospective members of the constitutional convention cannot be officially validated unless procedures for determining their validity have been adopted and a presiding officer has been chosen who can then recognize a motion to that effect.

Table 1. The Opening Dilemma Attending the Creation of a Constitutional Convention

Note: The opening dilemma arises from the fact that no constitutional convention can avoid arbitrarily creating at least two of these three organizational elements: a presiding officer, recognition of the members, and adoption of rules of procedure. “Arbitrary” means acting in a manner that supersedes and is thus contrary to the convention's presumptuous legitimacy as the embodiment of the “will of the people.” The opening dilemma also applies to those legislative assemblies in which, on the one hand, all the members turnover in an election and, on the other hand, the chamber's legitimacy rests upon its autonomy from all other political institutions. For the example, the opening dilemma both theoretically applies to and has appeared in practice in the United States House of Representatives. However, because the United States Senate is a “continuing” body, the opening dilemma cannot appear when it reconvenes in a new Congress.

Put another way, a presiding officer (most commonly, the president of a constitutional convention) cannot be democratically selected in the absence of an electorate (credentialed members) who are able to vote. And members are unable to offer and dispose of motions that might otherwise certify them as delegates if there is no presiding officer who can recognize them for that purpose. In the absence of such an officer, their motions (speech acts) are formally meaningless. Finally, in the absence of formal rules (which, like a presiding officer, must be democratically approved), members cannot even perform simple but necessary functions such as closing a debate so that the assembly can make a decision. Thus, at the very beginning of such an assembly, when the gathering is attempting to organize itself for the purpose of crafting a new constitution, there must be and always will be arbitrary decisions.Footnote 9 These arbitrary decisions resolve the opening dilemma confronting the constitutional convention by imposing by fiat at least two of the three preconditions: adoption of rules, selection of a presiding officer, and/or formal recognition of the members.Footnote 10

We will now turn to an instance when the opening dilemma was strikingly revealed in the organizing sessions of a constitutional convention. In this instance, the revelation that there was no way to proceed without making an arbitrary decision demonstrated, on the one hand, the fundamental connection between the “will of the people” and the creation of the convention and, on the other hand, that this connection must be superseded and violated in practice.

In November 1868, the people of the state of Illinois voted to hold a new constitutional convention by a slim majority of 1,408 votes (223,134 to 221,726). The state legislature subsequently issued the call for a convention to be composed of eighty-five members who would be elected from the same districts as those serving in the Illinois House of Representatives. The state legislature also provided that the election of the delegates would be conducted in the same way as in ordinary elections, that the delegates would be paid six dollars per diem plus travel expenses, and that the constitution adopted in the convention be submitted to the people for their approval. Eighty-five delegates were thus chosen in the November 2, 1869, election: forty-four Republicans and forty-one Democrats.Footnote 11

In 1862, Illinois had also convened a constitutional convention, but that constitution had been rejected, and the state constitution, which had been revised in 1848, was now two decades old. The motivation behind the new convention was a perceived need to modernize political institutions; enable policy responses to the rapid growth of corporate (primarily railroad) power; better provide public education to the children of the state; and address some of the now archaic (but still controversial) racial exclusions with respect to suffrage, militia service, and immigration into the state. Among other things, the constitution produced by this convention was intended to eliminate corruption by providing more secure and remunerative positions for government officials and impose more equitable rates for railroad operations (ultimately leading to the U.S. Supreme Court decision Munn v. Illinois, which upheld state regulation of rates charged by grain elevators). Illinois voters later approved the new constitution in its entirety (the primary text and eight separate propositions) in a referendum.

2. The 1869 Illinois Constitutional Convention

The delegates to the Illinois Constitutional Convention assembled in the state capitol building in Springfield at about half-past two o'clock on December 13, 1869.Footnote 12 The place and day (although not the precise time of day) had been designated in the same law that had authorized the election in which the delegates had been selected. And to that extent and that extent only, the convention was the creature of the legislature that had enacted the law.Footnote 13

The first entry in the convention record is an announcement by one of the delegates, Lawrence Church:

Gentlemen: The Convention will please come to order, and that we may proceed by some system, (as we do not know the difference between the delegates here, and others), I move that the Hon. William Cary, from Jo Daviess county, take the chair, as temporary President of this Convention.

As is the case in almost all constitutional conventions, there was no presiding officer when the delegates assembled. There were also no rules and recognized membership. Thus, when Church called for order, he was acting upon his own personal authority, an authority that could be rejected by any other person in the chamber because the chamber was not yet organized. His reason for so acting on his own authority tacitly rested upon practical necessity (“that we may proceed by some system”) because, in fact, there was no procedural structure in place at that moment. One of the consequences of that lack of structure was that “we do not know the difference between the delegates here, and others” who might also be in the chamber. In other words, the delegates had not yet been recognized as duly elected, a precondition for their ability to act as agents of the people they ostensibly represented. As a first step in remedying these defects, Church moved that one of his colleagues “take the chair.” While utterly ordinary in and of itself, his initiative was still quite audacious in that no one had, in a parliamentary sense, recognized him for the purpose of offering this (or, in fact, any other) motion. In fact, without rules and in the absence of a presiding officer, no one could recognize him for the purpose of offering this motion.

In most such situations, the delegates informally and consensually agree to the temporary elevation of one their number as leader for the purpose of organizing the convention.Footnote 14 But this was not the case here. Ignoring Church's attempt to claim the floor, James Allen offered his own motion:

Gentlemen of the Convention: I desire to put in nomination Col. John Dement, of Lee county, as temporary President of this Convention. This is that gentleman's third term of service as a member of a Constitutional Convention, and I think that such an honorable experience is sufficient reason to justify conferring on him the honor of temporarily presiding over this body.Footnote 15

After Charles McDowell seconded his motion, Allen immediately called a vote:

Gentlemen: As many as are of opinion that Col. John Dement, of Lee, be elected temporary President of this Convention, will say Aye. [“Aye!” “Aye!” and applause.] Those of the contrary opinion, will say No. [“No!’ “No!” and confusion.]

Allen then summarily announced, “The ayes seem to have it. The ayes have it. [Applause and confusion.]” This rather preemptory proclamation would have seemed to have given Dement the post. However, Church immediately responded by calling a vote on the nomination he had made.

Gentlemen: As many as are in favor of Hon. Wm. Cary for temporary President of this Convention will say Aye. [“Aye!” “aye!” ”aye!” and applause.] The contrary, No. [“No!” “no!” and applause and laughter. “Cary!” ”Cary!” “Dement!” “Dement!”]

Although the record does not show that Church summarily pronounced his own candidate to have been elected, we can safely assume that was what happened. In any event, the two nominees ascended opposite sides of the podium. Dement went up the stairs “from the democratic (south) side of the hall,” while Cary went up “from the republican (north) side of the hall.” When they met at the presiding officer's chair, “they shook hands amid great laughter and applause.”Footnote 16

Dement and Cary had been sponsored by their respective party contingents: Dement by the Democrats and Cary by the Republicans. In nominating them for the post of temporary president of the convention, Allen and Church had played the role of spokesmen for their respective parties. All the delegates of course recognized that was the subtext for their actions, thereby partially legitimating what they had done. For example, Church's nomination of Cary was not viewed as arrogant effrontery but as collective audacity on the part of his party. Allen's response was similarly interpreted but from the perspective of the opposite party. However, that subtext and the obvious good humor with which the delegates enjoyed the spectacle should not blind us to the fact that this was a collision of wills unmediated by any consensual understanding as to what constituted the rules of the game. When Dement and Cary shook hands at the rostrum, neither one of them had been appointed temporary leader of the convention.

Lawrence Church once again proposed a solution to the assembly's dilemma.

Presidents—I say Messrs. Presidents, for there is some doubt in the minds of the members of the Convention as to who should be addressed by me as President. In order that this question may be settled, and settled, too, in such manner as gentlemen in deliberation should settle such questions, I move that there be a division of this Convention, and than none except members of the Convention vote; and, therefore, that those in favor of Hon. Wm. Cary for temporary President take the north side of the hall, and those in favor of Hon. John Dement take the south side of the hall, and that Hon. Milton Hay and Hon. John Scholfield be appointed tellers to ascertain which has the larger number. With that, all, I suppose, will be content.

There are several aspects of Church's motion that deserve attention. First, although he, along with the rest of the delegates, understood that neither of the two “presidents” had been formally elected to the post, he appealed to them for recognition because, under the circumstances, that was all he or anyone else could do. The assembly absolutely required a leader in order to proceed with the organization, and if Dement and Cary were not to play that role, the delegates would be thrown back into the same quandary from which they had just emerged. So Church was now appealing to them for recognition where, originally, he had audaciously just stood up and announced his motion. Second, he had moved that the assembly vote on the two nominee-presidents, dividing up the hall into Republicans and Democrats. This proposal simultaneously recognized the quasi-authority of the two nominee-presidents (in that Church was asking them to permit him to offer this motion) and impeached that authority (by tacitly admitting that neither of them legitimately occupied their position without an election).

Third, Church had implicitly acknowledged that almost all the delegates in the chamber possessed a partisan political identity that strongly structured their orientation toward the proceedings, deeply informed how they interpreted the parliamentary situation, and, at the same time, appeared to promise a solution to the opening dilemma of the convention.Footnote 17 Finally, Church “supposed” that all the other delegates would be “content” with his proposal because consensus would solve all the procedural contradictions attending this highly irregular, from any parliamentary perspective, proceeding. In fact, consensual understandings are the routine method for resolving the opening dilemma in democratic institutions, and this situation, although far more complicated than most, was no more pregnant with procedural contradictions than any other.

However, James Allen was not about to concede the initiative to Church, declaring:

Mr. President: The gentleman is out of order. I think it is too late for the gentleman to call for a division, inasmuch as the division was not demanded until after the presiding officer had taken his place at the desk.

Here, Allen first declared Church to be “out of order,” a phrase describing an action that violates parliamentary rules. However, the phrase presumed that rules had been adopted, which, of course, had not yet happened. Even if they had been adopted, the convention lacked, as we have seen, a presiding officer who could decide whether the point of order was correct. By his use of the singular “president,” Allen was clearly asking Dement, his nominee for the post, to rule on his point of order.Footnote 18 And when he said that “it is too late” for a division, he also clearly implied that Dement had already been elected president of the convention. Underlying all of this is Allen's expectation (or, more likely, hope) that Dement would now step forward to the podium and claim the office by declaring Church to be “out of order.” If Dement had done this, there would have been, of course, no reason for the Republicans to have respected his construction of the situation. The result might have been pandemonium within the chamber if the Republicans contested the Democratic coup d’état. Alternatively, the Republicans might simply have bolted the convention. But, whatever happened, the opening dilemma was not going to be resolved in that way.

However, the two nominee-presidents had evidently been discussing the situation up on the rostrum. Dement now stepped forward to the “president's desk” and pleaded for harmony.Footnote 19 It was now Cary's turn to speak:

Gentlemen of the Convention: I cordially acquiesce in the remarks which have fallen from my honorable competitor, Colonel John Dement, of Lee county; and I suggest that the roll be called, or a division be had, as mentioned by the gentleman from McHenry [Mr. Church], and I will be satisfied with the result, be it as it may.

By aligning himself with Church and Cary, Dement clearly undercut Allen's ostensible role as spokesman for the Democratic party. Allen's objection now appeared entirely personal, inasmuch as Dement, the intended beneficiary of that objection, refused his assistance. By nominating him as the Democratic candidate for temporary president, Allen had recognized Dement's authority as a significant figure in the Democratic ranks, if not his party's leader in the chamber. Dement had now used whatever authority he had to oppose Allen's objection. But more importantly, because we might otherwise overlook the fundamentals of this situation, Dement and Cary were collectively claiming the role of temporary president(s) of the convention. They could not have made this claim had they disagreed. But by concurring, they could go a long way toward establishing their own legitimacy, even if that legitimacy was limited to the mere taking of a single vote. Since their authority ultimately rested upon the saliency of party identities as a structuring feature of the assembly, their ability to suggest that a consensus existed with respect to a division of the assembly once again demonstrated that party alignments within the chamber had to be taken into account.

2.1 The Convention Roll

The delegates seemed to have warmly embraced the proposal for a division, and many of them yelled, “Call the roll.” Lawrence Church formalized this request, saying, “Let the roll be called,” and adding, “I ask for the yeas and nays.” In response, the delegates called out “ayes and noes, ayes and noes.” However, just as the delegates were readying themselves for the vote, Allen again sought the attention of the presiding officer: “Mr. President….” At the same time, the temporary secretary of the convention began the roll, calling out “John Abbott—.”Footnote 20 Allen persisted and then objected to a roll call vote because: “We have no other means, in our present condition, of taking the vote of the Convention except by tellers.”

Given what we can surmise from the subsequent course of the convention's deliberations, Allen was apparently objecting to a recorded vote because the convention roll had not yet been approved. He evidently did not want a recorded vote because it would imply that the convention roll, whatever it might be, had been approved, and at least from his perspective, there might have been something or someone on that roll that he might have wanted to change. Because a division of the chamber in which tellers simply counted the delegates on each side of the question would not have involved approval of the roll, Allen wanted the chamber to use that method of voting.Footnote 21

From our perspective, however, the situation again displays the theoretically irresolvable qualities of the opening dilemma. The convention simply did not have a recognized membership that could legitimately do the voting, regardless of whether the delegates were simply counted or their names were individually called. A division of the chamber partially veiled the dilemma by making it seem as if the members “naturally knew” who had membership standing and who did not and thus would have exercised social pressure or some other device to prevent those from participating who were ineligible to vote. But the bottom line is that in the initial organization of the democratic assembly, as is the case for all democratic assemblies, there was simply no method for determining who was eligible to serve as a member.

Allen appears to have temporarily won this point, and the assembly was now preparing to vote for temporary president by tellers. However, Dement raised the leadership question once again. Standing at the president's desk with Cary right beside him, Dement made light of their predicament:

There is an embarrassing question before the Chair—the question of who has the right to put the question. [Laughter.]Footnote 22

In formal parliamentary terms, he was, of course, correct; the assembly did not yet have an acknowledged presiding officer who could put the question to the delegates. However, the social situation very strongly implied that, if Dement and Cary worked together, the delegates would follow their lead. At this point, one of the delegates, Milton Hay, suggested that

for the sake of harmony and peace, that the gentleman at the Secretary's desk be allowed to read the roll; and that the Convention hear the roll which he has made up.Footnote 23

Church immediately backed Hay's suggestion: “Let us hear the roll.”

This “roll” was a copy of a list of delegates compiled from the official election returns received from the counties. The list had been prepared by the Illinois secretary of state and then given to the convention. In many situations where a state constitutional convention or lower chamber of a legislature was initially organized, such a list served as a temporary membership list until the assembly could determine for itself who would or would not be a member. It should be stressed that this list had no more authority or standing in any convention or assembly than what the delegates wished to give it. Onias Skinner, one of the delegates opposed to using this list, succinctly summarized the limits of the secretary's role:

The duty of the Secretary of State is this, and no more; to attend at the opening of the body; to furnish the body with such documents, paper, stationery, etc., as the delegates may require. He has no power to present a roll for the government of this body in any respect whatever…. He has no power to come here with his roll, and say, A, B, and C are delegates to this Convention. The roll in his possession has no more vitality than simply an abstract copy of record in the county court, which is filed in his office and preserved as a mere duplicate.

While Skinner was undoubtedly correct, there was simply no way for the assembly to determine for itself who would or would not be a member.Footnote 24 Simply put, one of the preconditions for that determination was that the assembly formally recognize who should vote on the determination, a precondition that threatened to tie up the assembly in an infinite regress.Footnote 25

The convention secretary then read the list of delegates for the information of the assembly. This, however, was not the same thing as a calling of the roll, in which members would be asked to respond to their names. Such a call would constitute a major step toward determining who was a member of the convention because those whose names were not called would then have to establish their credentials another way. After the list had been read, Church moved that the roll be formally called and asked the delegates who favored calling the roll to answer “aye” and those who opposed to respond “no.” The record states that the “vote was accordingly taken,” apparently solely on Church's initiative. Immediately after the vote, Church declared that the “ayes have it.” However, many of the delegates disagreed, yelling out “no, no.”

Having encountered intense opposition, the whole proceeding fell to the floor, and the assembly again was at a stalemate. John Dement once more stepped into the breach:

Let me remark to the Convention that it seems to have no other officers selected from this honorable body to preside on this very momentous occasion, than the Hon. Mr. Cary and myself. We are perfectly willing that the questions that are propounded to the Chair shall be announced to the Convention by us, alternately, and in that way this matter can be easily settled.

This proposal prompted Elijah Haines to suggest an alternative method of creating a convention roll:

I am a member [of the convention], for I have a certificate to that effect. I make this suggestion, then (and I think it is the only one that can be made), that our certificates be all handed up to these two gentlemen [Dement and Cary]; that a roll be prepared by them, and that the members entered upon that roll proceed to select a temporary President.

The certificates to which Haines referred had been issued by the county or counties that composed the districts from which the delegates had been elected. The delegates (or at least most of them) had carried these certificates to Springfield, and Haines was suggesting that they now be turned over to nominee-presidents for the purpose of constructing a convention roll. This proposal would thus have sidestepped the mediating role of the Illinois secretary of state, although the information on the certificates in the possession of the delegates should have been identical (or nearly so) to the election returns reported by the Illinois secretary of state.

At this point, Skinner raised three issues that seemed to him to counsel against a speedy organization. The first was that “some claiming their seats in this Convention, as delegates, are not upon [the secretary of state's] list.” For that reason, the list could not be used as a temporary roll because it was incomplete. The second was that some of the delegates had not yet arrived in Springfield. He urged that the organization be postponed until all of them had arrived and could participate in the proceedings. Finally (and rather technically), he said that opening the convention at 2:00 in the afternoon was an arbitrary interpretation of the law. While that law designated December 13, 1869, as the day the convention should assemble, it did not say at what hour on that day the convention should assemble. In all this, Skinner was clearly speaking as a Democratic partisan. He felt that a postponement would allow the party to realize its full strength within the assembly, and when it did, the roll could be perfected to the best advantage of his party.

However, Skinner himself had informally agreed to 2:00 as the hour for opening the convention. Lawrence Church must have thus been a little taken aback, as he pointed out that the time had been selected in response to “a special request of the gentleman and his friends.” Henry Bromwell, like Church a Republican, then entered a full explanation into the convention record.

If the President will permit, I will say in response to the gentleman, the idea of convening at two o'clock arose in this manner: The gentleman from Crawford [James Allen, a Democrat] and myself, talked about an hour, and suggested to each other that some hour should be fixed; and we agreed, at first, that it should be three o'clock, and see who wanted it at that hour. We talked to half dozen or so, and it was suggested that the days were so short—three o'clock being pretty near dark—that two o'clock would be better; and we agreed to that, and everybody fell in with it, until perhaps thirty or forty had been spoken to on both sides of the Convention. That is all there was of that, so far as the time was concerned.

So the time had been informally agreed upon prior to the opening of the convention and had been set by consensus in a discussion heavily structured by partisan identities. If Skinner now impeached the legitimacy of that informal agreement, he was implicitly attacking either the integrity or good sense of his own party colleagues. But this apparently did not deter him, for he replied that “these gentlemen [had no authority] to make their arrangement among themselves, consulting with whomever they may happen to find hanging around the hall of the State house, in one office or another, or in this room.”

Because there were eighty-five delegates in the convention, the consultation among “thirty or forty” of them had actually been quite inclusive. And, if Church had correctly stated that Skinner himself had requested that time, Skinner's objection was both rather tardy and uncollegial.Footnote 26 However, we should not overlook the point that no one could invoke an authority, other than this informal agreement, for designating 2:00 as the hour for opening the convention. On that point Skinner was entirely correct.

But Skinner was already embarked on a tactic that he hoped would gain his side the time they needed. And Church recognized it for exactly what it was: a filibuster.

If the gentleman will indicate about what time it is necessary for him to speak, we will proceed with the calling of the roll, and let him at the same time go on. It has been suggested to me that there is a limit to the length of time which a gentleman, claiming to be a delegate, may speak.

The problem here was that the assembly had not adopted formal parliamentary rules, and there was thus no means of shutting off debate. So Church was suggesting that Skinner, if he so wished, could continue to address the assembly while the roll was called. For their part, the Republicans were ready to concede what appeared to be a major stumbling block: Church, as the party spokesman, thus proposed “that the name which is said [by the Democrats] to have been omitted from the roll be inserted therein, and that the business go forward.”

Skinner ignored Church's offer and launched into a long harangue in which he repeated, again and again, that the secretary of the state had no authority to even offer a list of delegates to the convention and that the doors to the chamber had been “swung open” at 2:00 p.m. in utter disregard for the rights of the delegates to the convention.Footnote 27 Although he did not admit that he was simply playing for time, Skinner urged that the convention “should now adjourn until tomorrow at twelve o'clock meridian.”Footnote 28 Presumably, he would have yielded the floor for that purpose, but no one stepped forward to take up his suggestion. Although we might consider his rhetoric a little overheated, Skinner did justify his request in language that accurately referenced the central core of the convention's legitimacy: its direct and unmediated connection to the popular will. Referring to the members of both parties who had struck the informal agreement on time, Skinner charged that:

You present to an intelligent world, palpably and fairly—and you cannot avoid the consequence, you cannot conceal the fact from the good people of Illinois and the civilized world—this spectacle of an attempt at seizure upon, and organization of, a Convention of the people of the State of Illinois, based upon the bargain of three or four, five or six individuals; based upon the action of the Secretary of State, without the color of law.

The problem with all this, of course, is that Skinner had nothing to offer as an alternative beyond adjournment to the next day. And the time he set for opening the convention on that day was even more arbitrary, because it reflected only his own personal will—a will made extraordinarily powerful because he held the floor and would not give it up.

Still, there might have been something to his request in that there were delegates who, for one reason or another (including misinformation as to when the convention would open), had not yet arrived in Springfield. Westel Sedgwick, one of the Republican delegates, rose to the occasion:

I ask the gentleman how he knows the delegates are not all here? The roll has not been called, and the presumption is that they are here.

Sedgwick was, of course, suggesting that Skinner was protecting the rights of phantoms. If all the delegates were, in fact, in the chamber, then there would be no harm in proceeding. The problem, from Skinner's perspective, was that the method of determining whether all the delegates were in the chamber (i.e., calling the roll) was the very thing he wanted to prevent.

Skinner simply answered Sedgwick by saying, “The presumption is that, according to all human experience, they are not here.” He then continued his harangue, again with the evident purpose of filibustering the proceedings. Here, too, Skinner reminded his colleagues of the rather unusual position in which they were placed. If they were to make an error in the organization, there would be “no appeal” to a higher authority because there was, with reference to the state of Illinois, no higher authority than the constitutional convention itself. And, “as there is no remedy, and you [referring to the Republicans] have the power” to effect a partisan organization and thus “can effect a revolution [in which] to carry out your preconcerted plans—you are invulnerable, because there is no power but the great Jehovah can avert the consequences.” This would be “a revolution, according to the understanding of mankind. And if you can consummate it, make the revolution effectual—then there is no remedy.” Once more, Skinner's rhetoric is perhaps overblown but still rested on a fundamental recognition that a state of nature existed within the bounds of a constitutional convention, a state of nature that did not admit and could not admit of any higher authority than what would be created within it.Footnote 29

In the midst of Skinner's observations on revolution and Jehovah, James Allen asked if he might “interrupt a moment.” Allen then brought the filibuster back to Earth by identifying the crux of the problem and offering a solution:

It seems there are some errors on this roll. I desire to propose to the gentlemen of this Convention an adjournment until some hour tomorrow. And we ask that the two gentlemen (laughter) prepare a corrected list of the members sent to the Convention, so that they may present it. We are anxious to have a speedy organization.

Because he, like Skinner, was a Democrat, Allen was probably speaking for the both of them and other party colleagues as well. And, like Church previously, he seized on the quasi-leader roles of the “two gentlemen,” Dement and Cary, as possibly effecting a compromise by asking them to jointly correct the list of delegates provided by the Illinois secretary of state. In the meantime, the convention would adjourn until the next day.

Church responded for the Republicans by stating that he favored, as consistent with the “forms of law,” an alternative method of correcting the roll in which

the roll-call would have proceeded. Any gentleman who is not upon the list would have been placed upon it, and our temporary organization would have been effected; and then, if adjournment should have been required to further the organization of the Convention, of course we would have been governed by the circumstances. All we ask is, that we may effect a temporary organization, and not be here to lag and mope away the day, but act like reasonable men.

In the course of his remarks, Church deplored the way in which Skinner had characterized the Illinois secretary of state, who “should be treated with proper respect” and termed Skinner's harangue a “factious interruption … made for what purpose we cannot conceive.”

Allen and Church had thus offered two alternative methods of creating a temporary roll of delegates. In some ways, the two methods appeared to be very similar in that they would both use the Illinois secretary of state's list as a template and would consensually correct mistakes on that list. But there was a very important difference between them that meant everything in terms of party interests in the convention. Allen's method would allow the convention plenary authority, through its two quasi-leaders, to construct the roll. Because the Illinois secretary of state's list would be nothing more than a convenient starting point for this construction, there might be substitutions in which one man claiming to be a delegate would be displaced by another. Church's method, on the other hand, would have conferred much more legitimacy upon the Illinois secretary of state's list by making it prima facie evidence that a particular man should be considered a member-elect. If the right of a man to a seat at the convention were challenged, it was not entirely clear what would happen because Church had himself talked about corrections. But normal practice, in state and national legislatures, was to note the challenge and give those men their seats until the challenges could be resolved. Since the parties were so closely balanced in the convention and because most of the challenges would be made by Democrats, the Democrats feared that Church's method would advantage the opposition. From our perspective, however, this possible partisan advantage is rather unimportant. What is more significant is that these two alternatives were equally arbitrary in that, despite Church's appeal to the “forms of law,” there was simply no way to confer more legitimacy upon one, as opposed to the other. The opening dilemma was thus just as firmly ensconced as it ever was.

When Skinner charged that the Republican proposal was politically motivated, Church answered:

We [the Republicans] have no partisan object to accomplish by pressing this matter. But we repeat that the hour of two o'clock was the hour, as every one, I suppose, knows, arranged for our meeting, with the concurrence of all parties. And now I will suggest that this body adjourn until tomorrow morning at ten o'clock. This is proposed with the understanding that this opposition [evidently referring to Skinner's filibuster] will be withdrawn, and that no further embarrassment will be offered to the organization of this Convention.

Church was thus acceding to Allen's request for an adjournment while attaching conditions. However, there was still no apparent agreement on a method for constructing a roll.Footnote 30

Stating that he wanted to make an explanation, Allen admitted that “I did agree with my friend here [Mr. Bromwell] that the hour of two o'clock was a very convenient time for us to get together,” thus confirming that a consensus on time had been reached between the parties. He then explained that the Democrats had, just after the convention opened, “received a telegraphic dispatch from a member elect, that owing to the severe illness of his father he had not been able to leave [home]. He will probably be here tonight or tomorrow.” So, in fact, one of the motives behind Skinner's filibuster was merely to delay the proceedings until this person arrived.

At this point Samuel Hayes, one of the Democratic delegates, rose and summarized the situation in which convention found itself. Since his summary closely conforms to the state of nature interpretation of the convention, it is worth a glance or two. After discussing the various kinds of evidence that might document the election of a delegate, Hayes launched into a broad theoretical description of just what the assembly was when it made a constitution.

I hold the doctrine that the people of the State of Illinois are sovereign, within the limitations of the Constitution of the United States, and that they have the right, within the limitations of that constitution, to frame and remodel their organic law. I hold that the power cannot be taken away from them by representatives of the people who are elected merely to pass ordinary acts of legislation, and I therefore hold that it is incompetent for the Legislature to restrict the representatives of the people elected to frame the organic law, in regard either to the mode of their organization or to the extent of their power after they have been organized….

I hold, then, that while the Secretary of State is bound to attend upon the proceedings of the Convention—the law requiring him to do so—the Convention is the only judge of the election returns and qualifications of its members—and I think that gentlemen of all parties will agree to that proposition.

When we meet together in this hall, we are only prima facie members of the Convention. We meet here and recognize one another as persons who are presumed to be members of the Constitutional Convention. We generally have no difficulty in selecting a temporary President, for the reason that the office of the temporary President is merely to secure the regular organization of the Convention, by presiding over its proceedings, and securing the vote of those who appear to be members.

While this was a particularly lucid analysis of the situation, executed at a high level of abstraction, Hayes did little more than confirm that the assembly was still securely lodged in the opening dilemma. Acknowledging the sovereignty of the convention over its own proceedings merely indicated that the convention alone was responsible for resolving that dilemma.Footnote 31

2.2 Election of the Temporary President

When Hayes sat down, however, the partisan stalemate began to break up. First, Thomas Turner, one of the Democrats in the assembly, stated his belief (formed “after consulting with a number of the members”) that “there is but one error in the Secretary [of state]'s list.” If the delegates were to “consent that his name be called,” the Democrats would be willing to proceed to elect a temporary president because “every gentleman is [now] present whom we have any reasonable cause to suppose will be present within the next two or three days.”

Turner's suggestion appears to assume that the member or members the Democrats had been waiting for had already arrived.Footnote 32 The only other obstacle in creating a convention roll was the status of this one member from Du Page County, who, although he had the proper certificate of election in hand, did not appear on the secretary of state's list. Suggesting that he himself had offered to place that delegate's name on the roll much earlier in the proceedings, Church immediately agreed to this solution and the Republicans were on board. The assembly then immediately proceeded to call the roll, as corrected, with each of the delegates announcing as they responded whom they favored for the post of temporary president. As they voted, some of the Republicans explained that they were voting for John Dement out of deep respect for his long service to the state, including membership in the 1847 and 1862 Constitutional Conventions. Other Republican delegates evidently abstained on this vote as well. As a result, Dement easily defeated Cary, 44 to 32, and was subsequently escorted to the president's chair.

After the newly elected temporary president gave a short speech, the convention turned to the election of a convention secretary. Here the partisan balance in the convention was starkly evident as the Democratic nominee, Harmon G. Reynolds, and the Republican candidate, George H. Harlow, tied at 42 votes apiece. Two delegates, one a Republican and the other a Democrat, then rose and offered motions that the nominees be considered “temporary secretary” and “temporary assistant secretary” of the convention.Footnote 33 This suggestion was approved, and the convention then elected two temporary doorkeepers, one from each party, as well.

2.3 Oath of Office

Now that temporary convention officers had been installed, the assembly turned to the task of formally recognizing the prospective delegates as members of the convention. In many legislative bodies and constitutional conventions, members are confirmed by taking an oath of office. The oath simultaneously performs two functions. On the one hand, the member must step forward and voluntarily take the oath, thereby symbolically demonstrating that the member is willing to serve. On the other, eligibility to take the oath confirms that the assembly recognizes the delegate as having all the rights, obligations, and privileges of membership. Like everything else in a constitutional convention, the assembly has total control over the form that the oath will take. In this instance, Lawrence Church proposed that the oath take the following form:

You do solemnly swear to support the Constitution of the United States, and of this State, and to faithfully discharge the duties of your office as members of the Convention. So help you God.

This oath may seem almost completely ordinary and thus devoid of controversy. But it was not.

After the clerk had read Church's resolution, James Allen immediately rose and moved to strike the words “and of this State” from the oath. The reasons he gave for this motion go to the very heart of the state of nature in which the convention deliberated.

I do not see how we are very well to alter and amend our Constitution, or any provision of our Constitution, while taking an oath to support its provisions. I move to strike out “and of this State” from the resolution, so that the oath may be taken to support the Constitution of the United States and faithfully discharge our duties.

In sum, Allen was contending that no one could support the existing Illinois State Constitution and also, at the same time, be engaged in a collective effort to replace that constitution with a new document. As he put it,

It … would be an absurdity for us to take the oath solemnly to observe the provisions of the Constitution of the State, while we are engaged in taking to pieces that Constitution and substituting something else for it.

Anticipating what would turn out to be the Republican position on this issue, Allen also said that he was “aware that the [Illinois] Legislature has prescribed the oath which this body should take, but not believing that the Legislature had power to prescribe the form of oath to be administered to the members of this body, I make this motion to strike out.”

Church rejected Allen's interpretation by contending that their collective task to “revise, alter or amend the Constitution of Illinois” was, in fact, a process entirely framed by that same constitution.

Though we are here to take to pieces, examine, correct and revise that instrument, we are here to do it in a method pointed out by that instrument, holding our power and authority from that instrument, and from a law made in pursuance and protection of it, under which law we are required to take the oath to support the Constitution of the United States, also that of the State of Illinois, and also the usual oath of office, to discharge our duties here.

Church's position thus had two parts. The most important was that they could only change the constitution within a process authorized and set out within that constitution. In other words, the constitution both anticipated and sanctioned the process in which they would amend it. They were thus acting in accord with its provisions even as they changed those provisions. He also noted that the state legislature, in calling the convention together, had specified this oath for its delegates and they were thus bound by law to use it. Church rejected the notion that they were

a revolutionary body, resorting to first principles,—the elementary right of revolution,—but are simply here as a legally constituted body, acting under a properly constituted power.

If they had gathered together to change the state constitution outside the color of law, they would be making revolution, and thus swearing an oath to support the state constitution would be a complete and utter contradiction. But, because this was an ordinary process, fully enjoying the sanction and drawing upon the authority of the state, the oath he offered was perfectly consistent with their obligations and responsibilities.

Henry Bromwell agreed with his Republican colleague and drew a scenario for the delegates that would starkly contrast with the situation in which they found themselves.

We are not in the position of a body of men on an island, who should assemble, after being cast away in a storm, and attempt to lay the foundations of a government. Here the foundations are laid. The Constitution is made. The machinery of the State government goes forward. In that machinery it is provided that whatever alterations or amendments may be desired, shall be made in a certain manner, in a manner conformable to certain laws, in a mode pointed out and ordered beforehand.

One difference between the position Allen assumed and the Republican interpretation drew upon what would happen if the convention were to fail to adopt a new constitution. All three men clearly recognized that, if the convention were to fail, the people of Illinois would not revert to a state of nature because the current state government would remain legitimate, with all its powers still in force and all its officials exercising its authority. For Church and Bromwell, this fact was proof positive, along with the clear sanction for their actions by the state, that they were well within the ambit of the state constitution as they deliberated.

Allen clearly accepted the premises but rejected the conclusion. For him, the delegates would step into a state of nature, albeit limited, when they began to deliberate. They could thus appropriately swear an oath to the national constitution because that charter was not suspended as they deliberated. In fact, one of the constraints under which they would work was that nothing they adopted could conflict with the United States Constitution. But the state constitution was necessarily suspended with respect to the delegates. While this suspension was very narrowly limited to their deliberative roles in the convention, they could not simultaneously deliberate on a constitutional revision and pretend, at the same time, that they were supporting the state constitution.Footnote 34

All three men also believed that, as Bromwell put it, the Illinois “Legislature is entirely powerless to prescribe the scope of our action when once [the constitutional convention] is assembled in due form.” But the Republican delegates emphasized that, once they were finished, the revised constitution would be submitted to the people of Illinois for approval in an election. That meant, for one thing, that their labors were provisional, not definitive. Furthermore, because the revised constitution would only come into being when and if the people voted their approval, the existing state constitution would still be in place once they adjourned. And, because that election would be held under Illinois law, the existing state constitution thus controlled both entry into (when and how the delegates were elected) and exit (popular approval of the revision) from the convention. To pretend otherwise, again in Bromwell's words, was to “jump at once from the control and order of law into the wild field of anarchy, and say that we are unlimited in our powers.” If the convention were to adopt such an attitude, “society will be remitted to its first principles [and the delegates and the Illinois people] shall be but a step from barbarism.”

The prospect of a return to the state of nature clearly disturbed some of the delegates. The Republicans appear to have seized upon the oath as a way of preventing a potential slide into anarchy in that, if the delegates swore to support the state constitution, they would be at least committed to a postconvention process in which an election, sanctioned and overseen by the state legislature, would be required for ratification.Footnote 35 In other words, by swearing such an oath, the delegates would pledge to support the process of ratification currently set out in the existing state constitution. If they did not swear to support the state constitution, the delegates could possibly change that process by, for example, simply declaring their revision to be ratified before they adjourned. The oath proposed by the Republicans would thus constrain the decisions of the conventions before the delegates began to deliberate.Footnote 36

During this debate, the Democrats never said that they wanted to supersede the ratification process currently set out in the state constitution. What they did say, and said repeatedly, was that they could not honorably swear to support the state constitution and, at the same time, deliberate on its revision. In that sense, the two sides on this question were speaking past one another. Even so, the Democrats did seem to interpret the convention's sovereignty much more expansively than did the Republicans. William Archer, for example, had also served in the 1847 Illinois Constitution Convention in which this very issue had been

very fully and very elaborately discussed; and I know that it was the opinion of some of the most eminent jurists who held seats upon that floor that no oath at all was necessary—that that Convention was an elementary body, deriving its authority from no source; that absolute sovereignty and paramount authority were the attributes of such a body; that it owed allegiance to no person and no body of men; that it was, as it were, the people en masse, and that no oath at all was necessary.

The outcome of that debate in 1847 was that the delegates swore an oath that omitted any reference to the state constitution. Archer then concluded that

the act of the people, in calling this Convention, is a resumption of power of government into their hands, and the election of delegates to this Convention is a transfer of that sovereignty to this body; and if it be sovereign, I am at a loss to know to what authority it is amenable, except to the Federal Constitution, to which, under God, every government, State and Federal, and all State Constitutions must conform.

While Archer did not explicitly say that the delegates could, in fact, legitimately specify a change in the process through which their new constitution would be adopted, there is clearly nothing in his position that would prevent such an assumption of authority. And that is what had the Republicans worried.

The debate over what the oath should entail and how it would be administered consumed several days.Footnote 37 At one point, one of the Democrats suggested a substitute for the oath Church had presented.

Resolved, That the delegates to this Convention take the following oath: “You do solemnly swear to support the Constitution of the United States, and faithfully discharge the duties of delegates to revise, alter or amend the Constitution of the State of Illinois.”

Because this would place determination of what “the duties of delegates” might be in the hands of the individual delegates, the substitute effectively evaded the question of whether or not the delegates would be pledged to support the state constitution. Nothing came of this suggestion.

Later on, the Mayflower Compact was alluded to in support of the Republican position.Footnote 38 At another point, one of the delegates presented a catalog of past state constitutional conventions in which he showed that many of them had required no oath at all.Footnote 39 After more debate, Thomas Turner moved that the convention “proceed to take the question” upon the alternative oath that had been offered as a substitute amendment. This motion was immediately seconded. After more debate, Orville Browning (the member who had previously said that he stood “outside of all party organizations”) offered yet another alternative oath:

That I will support the Constitution of the United States, and of the State so far as its provisions are compatible with, and applicable to my position and duties as a member of this Convention, and that I will faithfully discharge my duties as a member of said Convention.

The Democrats, possibly recognizing that the vote was going to be close and that Browning's oath was little different from their own, accepted his version in place of their alternative. After much more debate, the convention finally voted, pitting Browning's oath against the one originally offered by Church. Browning's alternative prevailed, 44 to 40. The convention then adopted Browning's oath as the one they would use to swear in the delegates. The assembly then adjourned.

On the next day, however, the delegates soon discovered that the controversy over the oath was not quite finished. James Allen suggested that the assembly might, by unanimous consent, allow delegates to choose to swear the oath the convention had adopted or, alternatively, the oath passed by the legislature. However, Charles Emmerson, a Republican objected, saying,

I must confess that the taking of a multiplicity of oaths does not look proper to me. It seems to me that when we organize we all should take an oath; and that every member should take the same oath, and not a number of different oaths.

This question was left in the air as the delegates, twelve at a time, came to the bar of the chamber and were sworn by Samuel H. Treat, a judge serving on the bench of the United States District Court for Southern Illinois. Then the question again reverted to the legislature's oath. After much parliamentary maneuvering and debate, the convention decided to allow those delegates who desired to take the legislature's oath, in addition to the convention oath, to rise in their places and be sworn by Judge Treat.Footnote 40

2.4 Election of a Permanent Convention President

Now that the delegates were sworn the convention had defined its membership. It also had a serviceable presiding officer in John Dement, the temporary president, and the assembly now turned its attention to the election of a permanent president. Charles Hitchcock, a Democrat, was subsequently elected with none of the existential angst that had accompanied some of the other stages in the assembly's organization.Footnote 41

2.5 Adoption of Procedural Rules

On the afternoon of the fourth day of the convention, the assembly finally adopted procedural rules. They came in the form of a resolution authorizing the appointment of a committee “to prepare and report rules for the government of this Convention.” Until that committee reported back to the assembly, the rules of the previous constitutional convention, held in 1862, were to be enforced. The following day, December 17, 1869, the Committee on Rules reported back to the convention. After debate, their proposed rules were adopted by voice vote.

3. Summary

One way to think about the relationship between the opening dilemma and the will of the people is to distinguish between (a) the clearly evident and empirically demonstrable existence of “individual wills” and (b) the metaphysical collective entity that democratic belief constructs when it refers to the sum of those individual wills as the “will of the people.” At one level, this is merely a terminological conceit in which the “will of the people” is rhetorically deployed. But on another and often more important level, the will of the people is explicitly manufactured out of the expression of individual wills. In order for that transformation to be legitimate in a democracy, we must first agree upon the algorithm that manufactures the metaphysical will of the people out of a set of individual wills. For example, we might simply count the individual wills with respect to a choice between two alternatives and decide that a majority is to be construed as the will of the people. That majority rule is probably the most commonly used algorithm in democratic practice.

The opening dilemma is more general in its implications because it demonstrates that the algorithm itself cannot be democratically chosen. In order to adopt an algorithm, the set of individual wills that are to be consulted must be defined, and paradoxically, defining that set of individual wills itself requires an algorithm. Put another way, at the very onset of the convening of a constitutional convention (and thus the founding of a democracy) there is a catch 22: The set of individual wills that will be processed in the algorithm must be specified before the algorithm is chosen but, if a people (or their representatives) are to democratically decide how to specify their membership, an algorithm for that purpose must have already been adopted. The only way to resolve this dilemma is to arbitrarily create an algorithm by fiat.

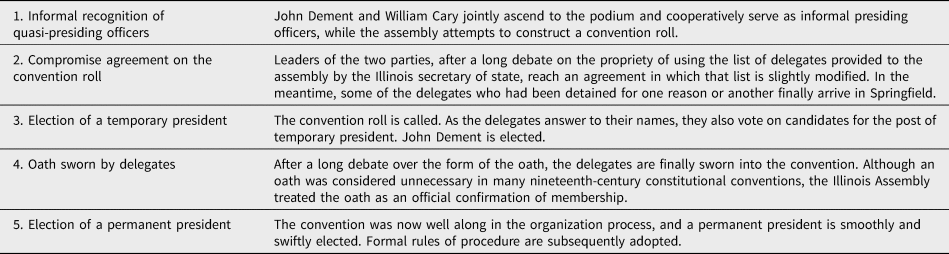

The 1869 Illinois Constitutional Convention directly confronted the opening dilemma and groped, sometimes blindly, toward an answer as it sought to discover what might be the least objectional arbitrary decision that might allow it to organize. The opening dilemma was resolved in stages, beginning with the highly irregular recognition of two delegates as quasi-presiding officers (summarized in Table 2).

Table 2. Stages in the Resolution of the Opening Dilemma in the 1869 Illinois Constitutional Convention

Although the course of this convention's organization was unique in many respects, the general form was quite common in the United States during the nineteenth century. Most assemblies would apparently open with the selection of a temporary presiding officer. In many cases, this selection was consensual. When it was not, as in the present case, the assembly would have to decide who could vote on the selection. After the selection of a temporary presiding officer, the assembly would then proceed to the construction of an official membership roll. When this was completed, the convention would elect a permanent presiding officer. Last and in many ways least, the assembly would adopt formal rules of procedure. By this point, the members, of course, had been offering motions and making points of order for some time.

Although the confusion was often amicable and even humorous, the opening moments of this convention amply illustrated the problems that can attend the opening dilemma. In the resulting deadlock, possible resolutions of the dilemma were constructed out of “general understandings” of the shared experience and values of the delegates. The delegates appealed to these understandings as they searched for the pivot upon which the convention could be levered into existence. For example, in the debate over what a “day” might be, the members cited legal interpretations that would have been at home in a court of law, thus appealing to the professional occupation of many of the delegates as lawyers. Similarly, the competing interpretations of the list of members presented by the secretary of state rested upon various understandings of the relation of the certificates forwarded by the county courts. These were treated by the Democrats as “matters of fact” of which the secretary had no more cognizance that did the delegates themselves while the Republicans gave much more credence to the list. The travel plans of the delegates, appealed to early on, were said to have been influenced by a general custom under which legislative assemblies began their deliberations on Tuesday because travel on Sunday was customarily understood to be a possible violation of the Sabbath, and it would take some members at least a day to arrive at the state capital.

The most pervasive reliance upon consensual understandings was common acquiescence to what was sometimes called “general parliamentary practice.”Footnote 42 In the absence of formal rules, what was considered appropriate and reasonable arose out of the prior experience of the delegates in other venues: most commonly the state legislature, but also city councils and party conventions. For example, Lawrence Church criticized Onias Skinner for mounting what we would call a filibuster.Footnote 43 Underpinning all these disputes was the understanding (indeed, certain knowledge) that most of the organization of the chamber would rest upon a division of the delegates into the two major party organizations: generally, the North (Republican) and South (Democratic) sides of the chamber.

The opening dilemma is theoretically irresolvable by purely democratic means. Without a presiding officer, a recognized membership, and formal rules of procedure, no assembly can democratically make a decision. However, assemblies have been, in fact, able to organize themselves for legislative deliberations without seeming to impeach their legitimacy as democratic agents serving the will of the people. One major contributor to their success is a shared orientation toward and respect for consensual political principles such as general parliamentary practice that allow delegates to act as if one of the legs of the opening dilemma—the absence of formal rules—had already been resolved.

Another is the intrusion of preexisting social and political identities. In many cases, for example, one of the formally organized political parties is commonly conceded to have a clear majority in an assembly once it is up and running. In such instances, many of the practical decisions concerning the initial organization of a chamber are made within that party and presented in the assembly to the minority as simply what is going to happen. When the majority party imposes its decisions on a convention or legislative assembly, its actions do not eliminate the opening dilemma, but it does make any resistance to its actions appear to be undemocratic obstruction. From that perspective, the problem facing the 1869 Illinois Constitutional Convention was that it was unclear which party would control the chamber when the assembly was finally organized.

In sum, a convention could not resolve the opening dilemma without appeal to dimensions of political life external and prior to the legislative session. Everything else being equal, the ease with which a convention could organize depended on how robust those dimensions proved in producing a consensual understanding on how to proceed. In some ways, strong challenges to this understanding threaten to throw the proto-assembly back into chaos by exposing those aspects of a political culture that are routinely (and often unconsciously) taken for granted or assumed. For example, when delegates pointed out that an assembly had not adopted formal rules of procedure, it was almost as if they were denying that they could share and thus communicate in the very language of legislative deliberations. Even the observation that the assembly had not adopted formal rules of procedure, which usually took the form of a point of order addressed to the presiding officer, required use of that deliberative language, a language that the observation simultaneously used and denied. Such challenges often, if not always, addressed the foundational role of the assembly in creating a democratic government. However, that foundational role is thoroughly suspended, as we have seen, between the horns of the opening dilemma.Footnote 44

In the opening moments of the 1869 Illinois Constitutional Convention there were at least three different levels of rhetorical abstraction. On the most mundane level, the delegates debated the specifics of the situation in which they were deliberating. These specifics included what evidence could legitimate the credentials of the members-elect, the proffering of commonsense resolutions of particular disagreements, and pragmatic suggestions that they take up other matters when they were stymied by a particular issue. On this level, the delegates practically confronted and dealt with the opening dilemma without recognizing it for what it was or that it was common to all such assemblies.

These exchanges frequently moved to a higher level in which the delegates cited what they considered to be persuasive precedents arising out of practice in previous constitutional conventions or metaphorical constructions of what they thought was reasonable arising out of personal experiences in their professions or political careers. Intended to generalize the situation in which the delegates found themselves by illustrating commonalities with other, similar venues, these precedents and metaphorical applications contended that political and social practice at other times and places could and should inform the present. As such, they constructed a fiction that could resolve the opening dilemma if the delegates accepted the precedent or metaphorical application.Footnote 45 As jerry-rigged acts of imagination, they were persuasive only to the extent that the political culture of the delegates allowed them to conceive of their relevance and applicability in the same way.Footnote 46

The most theoretically abstract level was reached when intense disagreement precluded pragmatism and imagination. For example, one of the most effective ways of rejecting the relevance of precedents and personal experience was to stress the sovereignty of the convention, a sovereignty that could not and should not be compromised by deference to external authorities, including past conventions. Whenever sovereignty of this kind was invoked, the delegates could be certain that they were impaling themselves on one of the horns of the opening dilemma (i.e., that the delegates were deliberating in a state of nature). They were similarly impaled whenever the delegates were reminded that the assembly's obligation to enact the people's will demanded an uncompromising devotion to democratic principles (e.g., that partisanship might inhibit a delegate's ability to truly represent his constituency).

In many assemblies (this Illinois Constitutional Convention was no exception), partisan identities and allegiances were criticized as fundamentally incompatible with pure representation of the popular will.Footnote 47 The delegates, of course, did not shed their party allegiances in the convention, but they were often compelled to present partisan proposals very circumspectly, using arguments that appeared to rest on anything but partisan interest or desires. The opening dilemma also showed its horns when delegates stressed that the way they deliberated would haunt the future peace and prosperity of their society. In all these ways, an insistence that the assembly democratically enact the will of the people threw the delegates upon the horns of the opening dilemma because there was just no way to both organize the convention for business and be completely faithful to democratic principles.Footnote 48 In all these things, the delegates only gradually came to understand that they had blundered into the opening dilemma because they had been entirely unaware of its existence and implications before they had gathered together.

At the beginning of all conventions and legislatures in which all the members are elected at the same time, there is thus something that we might, perhaps unfairly, call a “dirty little secret.” The secret is that any legislature organized for the purpose of founding a democracy must first lay its own foundation by violating, one way or another, democratic principles. And the reason that this can be termed a “secret” is that it is never openly admitted. The secret can also be called “dirty” in the sense that the violation of democratic principles impeaches the very authority of the assembly as it goes about the task of constructing the legitimacy of the democratic state it is founding. That fact opens the assembly and the delegates to the charge of hypocrisy at the very outset of their deliberations. However, we should always remember that the problem ultimately arises from an unavoidable contradiction in the logic of the situation and is thus not the product of a willful failure of virtue. Finally, whether or not this is a “little” secret usually depends on whether or not the delegates in the assembly share a wide, deep political culture.Footnote 49 If they do, they might not even notice the arbitrary ground upon which the opening decisions in the assembly are made.Footnote 50