Introduction

Eating disorders (disturbances in eating, weight, and body image) are serious psychiatric disorders with a lifetime prevalence of 2% globally (Swanson et al., Reference Swanson, Crow, Le Grange, Swendsen and Merikangas2011). Clinical and subclinical symptoms of eating disorders can cause significant distress to individuals and their families, substantially impair interpersonal relationships, and increase the risk of medical morbidities, psychiatric morbidities, and early mortality, due to physical health complications or suicide (Demmler et al., Reference Demmler, Brophy, Marchant, John and Tan2019; Swanson et al., Reference Swanson, Crow, Le Grange, Swendsen and Merikangas2011). Eating disorders are often studied as discreet conditions, such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder, but as diagnostic instability, non-specific eating disorders (Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorders), and subclinical symptoms are common (Micali et al., Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy, Calzo, Sonneville, Swanson and Field2015; Schaumberg et al., Reference Schaumberg, Jangmo, Thornton, Birgegård, Almqvist, Norring, Larsson and Bulik2018; Zanarini et al., Reference Zanarini, Reichman, Frankenburg, Reich and Fitzmaurice2010), studies using symptoms-based rather than diagnostic-based approaches are needed. Although most disordered eating onsets and peaks during adolescence (Demmler et al., Reference Demmler, Brophy, Marchant, John and Tan2019; Micali et al., Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy, Calzo, Sonneville, Swanson and Field2015), the course of comorbidity and associated risk factors remain poorly understood (van Furth et al., Reference van Furth, van der Meer and Cowan2016).

Approximately half of individuals with an eating disorder present with a comorbid personality disorder, most commonly (22%), borderline personality disorder (BPD) (Martinussen et al., Reference Martinussen, Friborg, Schmierer, Kaiser, Øvergård, Neunhoeffer, Martinsen and Rosenvinge2017). BPD is another serious psychiatric disorder, demarcated by emotional, behavioral, and interpersonal instability, and like eating disorders, is associated with premature mortality (Temes et al., Reference Temes, Frankenburg, Fitzmaurice and Zanarini2019). Prior studies that investigated the overlap between eating disorders and BPD were primarily based on adult women, clinical samples, and cross-sectional or short-term prospective data (Martinussen et al., Reference Martinussen, Friborg, Schmierer, Kaiser, Øvergård, Neunhoeffer, Martinsen and Rosenvinge2017). To date, no study has investigated co-occurring trajectories of disordered eating and BPD or delineated temporality at the time of symptom onset. Unraveling the joint trajectories of disordered eating and BPD symptoms will have implications for understanding the developmental and temporal patterns of these psychopathologies at the intraindividual level. Determining temporal precedence has been identified as a clinical priority (van Furth et al., Reference van Furth, van der Meer and Cowan2016), largely because knowing whether symptoms of eating disorder or personality disturbance come first has consequences for the timing and ordering of treatment. Intuitively, it may seem reasonable to predict that personality disturbance precedes other psychiatric problems, but there is evidence that poor diet quality and disordered eating often precede other mental health problems (Lee & Vaillancourt, Reference Lee and Vaillancourt2018; Marx et al., Reference Marx, Moseley, Berk and Jacka2017; Micali et al., Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy, Calzo, Sonneville, Swanson and Field2015).

Considering the increased risk of early mortality and morbidity associated with eating disorders and BPD and that a high-risk dual trajectory would be found in the data, we were interested in identifying the comparative contribution of antecedent risk factors. Presently, a major limitation of research on risk factors is the lack of disorder-specific etiologies. This is because most risk factors and outcomes follow the principles of equifinality and multifinality, in that many risk factors can lead to the same outcome, and one risk factor can lead to many outcomes (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996). Much research has examined contemporaneous risk factors for disordered eating and BPD features, and the selected risk factors in the current study build on this prior work and fit within a psychosocial framework. We focused on risk factors available in the data set that were non-age-overlapping and have shown the largest effects previously. For each modifiable risk factor, small reductions in their occurrence could significantly reduce the incidence of eating disorders and BPD. Therefore, we examined population attributable fractions (PAF), an epidemiological tool that quantifies the impact of risk exposure and clinical burden in populations (Mansournia & Altman, Reference Mansournia and Altman2018; Williamson, Reference Williamson2010).

Our selected risk factors were broadly characterized as sociodemographic (i.e., sex, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, household income, parent education), interpersonal (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, bullying victimization, bullying perpetration), and clinical (i.e., anxiety, depression, somatization, hyperactivity, impulsivity). In previous umbrella reviews and meta-analyses, interpersonal factors, especially childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and peer bullying victimization have contributed the largest risks to eating disorders and BPD (Lereya, Copeland, Costello, et al., Reference Lereya, Copeland, Costello and Wolke2015; Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Stubbs, Ricca, Moretti, Busatta, Carvalho, Dragioti, Favaro, Monteleone, Shin, Fusar-Poli and Castellini2021; Winsper et al., Reference Winsper, Lereya, Marwaha, Thompson, Eyden and Singh2016). Clinical factors, such as comorbid mood and anxiety disorders, and neurodevelopmental conditions, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have also been strongly implicated in the development of disordered eating and BPD features (Reference Lee and Vaillancourt2019a; Haltigan & Vaillancourt, Reference Haltigan and Vaillancourt2016a; Jacobi et al., Reference Jacobi, Hayward, de Zwaan, Kraemer and Agras2004, Lee & Vaillancourt, Reference Lee and Vaillancourt2018; Stepp et al., Reference Stepp, Lazarus and Byrd2016; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall, Krygsman, Boylan, Duku and Hymel2014; Winsper et al., Reference Winsper, Lereya, Marwaha, Thompson, Eyden and Singh2016, Reference Winsper, Hall, Strauss and Wolke2017).

In terms of sociodemographic risks, girls are more likely than boys to be diagnosed with an ED or BPD. Girls typically feel more pressure to be thin than boys, and attempt to lose weight by engaging in restrained eating (Buchanan et al., Reference Buchanan, Bluestein, Nappa, Woods and Depatie2013; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, Ricciardelli and Finemore2002) and extreme weight loss behavior (McCabe & Ricciardelli, Reference McCabe and Ricciardelli2005), while boys typically feel more pressure to be muscular than girls (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, Ricciardelli and Finemore2002). Sociocultural influences (e.g., media images, family and peer pressure, bullying victimization and perpetration) may drive expectations about body shape or size differently for boys and girls (Helfert & Warschburger, Reference Helfert and Warschburger2011; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Guy, Dale and Wolke2017; Knauss et al., Reference Knauss, Paxton and Alsaker2007). However, some research suggests that adolescent girls and boys may be more similar in their disordered eating behavior than previously thought (Latzer et al., Reference Latzer, Azaiza and Tzischinsky2012), as there appear to be few sex differences in meal skipping (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Skelton, Perrin and Skinner2016) and laxative abuse (Buchanan et al., Reference Buchanan, Bluestein, Nappa, Woods and Depatie2013). Similarly, research has indicated that girls score higher on measures of BPD features than boys (Haltigan & Vaillancourt, Reference Haltigan and Vaillancourt2016a; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall, Krygsman, Boylan, Duku and Hymel2014), but in adulthood, the clinical presentation of BPD among women and men is more similar than different (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Gunderson, Stout, McGlashan, Shea, Morey, Grilo, Zanarini, Yen, Markowitz, Sanislow, Ansell, Pinto and Skodol2003). Sex assigned at birth may thus be a key predictor of trajectory membership among adolescents. Other demographics, such as race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors, have been inconsistently associated with ED and BPD (Meaney et al., Reference Meaney, Hasking and Reupert2016; Stepp et al., Reference Stepp, Lazarus and Byrd2016; Wildes et al., Reference Wildes, Emery and Simons2001), while research suggests that individuals with an ED or BPD features are less likely to be heterosexual (Castellini et al., Reference Castellini, Lelli, Ricca and Maggi2016; Reich & Zanarini, Reference Reich and Zanarini2008; Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Sharp, Kalpakci, Choi and Temple2016).

The aims of the present study were to examine: (a) the course of disordered eating and BPD features, (b) joint trajectories and patterns of co-occurrence, (c) temporal precedence, (d) unique and shared childhood risk factors, and (e) the burden of probable clinical cases attributable to each risk factor, using data from a community-based cohort study that spanned five years of adolescence (age 14–18 years). Based on prior research, we expected that there would be a high degree of co-occurrence between disordered eating and BPD symptoms (Martinussen et al., Reference Martinussen, Friborg, Schmierer, Kaiser, Øvergård, Neunhoeffer, Martinsen and Rosenvinge2017), that disordered eating would be a stronger precursor to BPD features than the reverse (Lee & Vaillancourt, Reference Lee and Vaillancourt2018), and that all interpersonal and clinical risk factors would be significant predictors of disordered eating and BPD features (Lee & Vaillancourt, Reference Lee and Vaillancourt2019b; Lereya, Copeland, Costello, et al., Reference Lereya, Copeland, Costello and Wolke2015), but that more girls than boys would be in the high symptom trajectories (Buchanan et al., Reference Buchanan, Bluestein, Nappa, Woods and Depatie2013; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, Ricciardelli and Finemore2002; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall, Krygsman, Boylan, Duku and Hymel2014).

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from the Canadian McMaster Teen Study, a longitudinal study examining bullying, mental health, and academic achievement. In 2008, a random sample of children (N = 875) were recruited from Grade 5 classrooms (M age = 10.91, SD = 0.36) across 51 schools in southern Ontario. Participants have been followed up annually until age 26, with 80% (n = 703) of children participating in the longitudinal arm of the study (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall and Duku2013). The present study included data from 544 adolescents (77%) who completed measures of disordered eating and BPD features between the ages 14–18 years. The analytic sample was restricted to participants with data on disordered eating and BPD features at one or more time point.Footnote 1 The sample consisted of 56% girls, were majority white (76.3%; African/West Indian = 4%, South Asian = 3.5%, Indigenous = 2.1%, Middle Eastern = 1.6%, Asian = 1.4%, South/Latin American = 1%, other = 1.9%, and missing = 8.2% ), with a medium income ($70,000–$80,000). Almost two-thirds of the sample had parents with a Bachelor’s degree. Most adolescents identified as heterosexual (86.4%; Lesbian/Gay = 1.6%, bisexual = 9%, other = 3.6%).

Procedure

This study complies with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human participants were approved by the McMaster University Research Ethics Board (grades 5–8) and the University of Ottawa Research Ethics Board (grades 9–12). Each year, written parental consent and child assent were obtained. In Grade 5, data were collected during school hours using a paper/pencil survey. In subsequent years, adolescents completed a paper/pencil or electronic version of the questionnaire at home. Participation was compensated with a gift card that incrementally increased in value.

Measures

Disordered eating behavior

The Short Screen for Eating Disorders (SSED) was used to assess disordered eating behavior (Miller & Boyle, Reference Miller and Boyle2009). SSED items reflect behavior identified in the DSM-IV for eating disorders and items were verified by a team of ED specialists, psychiatrists, psychologists, dieticians, pediatricians, and social workers (Miller & Boyle, Reference Miller and Boyle2009). The SSED exhibit 83–97% sensitivity-specificity in predicting cases versus non-cases among girls and boys. The scale consists of 12 items rated on a 5-point scale (0 = never, 1 = a few times a month, 2 = once a week, 3 = 2–4 times every week, 4 = almost every day) and examines clinically significant behavior (e.g., “How often did you take diet pills?”; “How often did you vomit on purpose after eating?”). Items were averaged to create a composite score, with higher scores reflecting higher severity of disordered eating behavior. The measure had good reliability at every time point (min–max α = 0.75–0.82).

Borderline personality features

The Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children was used to examine self-reported BPD features from age 14 to 18 years (Crick et al., Reference Crick, Murray-Close and Woods2005). The scale consists of 24 items rated on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all true, 1 = hardly ever true, 2 = sometimes true, 3 = often true, and 4 = always true). A composite score was calculated at each time point by averaging the items, with higher scores indicating higher symptoms severity. Internal consistencies across time were excellent (min–max α = 0.90–0.91). Factorial invariance of the Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children has previously been established (Haltigan & Vaillancourt, Reference Haltigan and Vaillancourt2016b).

Risk factors

All modifiable risk factors were transformed into dichotomous variables to calculate odds ratios, relative risks, and population attributable fractions.

Sociodemographic factors. Sex assigned at birth was self-reported (boy = 0, girl = 1) and verified with parent reports. Race/ethnicity was based on a combination of self and parent reports and was dichotomized into White and non-White due to the low prevalence of most non-White racial/ethnic backgrounds. Household income was assessed using an 8-point scale using increments of $10,000. The median income for the province (Ontario) from which the students were recruited was $70,910 and for the city was $76,222 (http://www.statscan. gc.ca). The median income of our sample was $70,000–$80,000, which maps onto the city and province levels and represents a middle socioeconomic stratum in Canada, thus income was recoded as average (≥$70,000 = 0) or below average (<$70,000 = 1). When children were aged 11, parents reported their own highest level of education using a five-point scale (e.g., did not complete high school = 1; graduate degree = 5), which was dichotomized into <Bachelor’s degree = 0 or ≥Bachelor’s degree = 1 as above average incomes (≥$70,000) were clustered among those with university degrees. Adolescents were contacted at age 19–20 and reported on their sexual orientation. As there were low prevalence rates for each LGBTQ+ orientation, sexual orientation was dichotomized into heterosexual or LGBTQ+.

Interpersonal factors . Childhood bullying victimization and perpetration was measured from age 11 to 13 using an adapted version of the Olweus Bully/Victim questionnaire (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Trinh, McDougall, Duku, Cunningham, Cunningham, Hymel and Short2010), which consists of one general item “Since the start of the school year, how often have you been bullied at school?” and four specific items (i.e., physical, verbal, social, cyber victimization). Responses were on a 5-point scale (not at all = 0; many times a week = 4). The same items, with slight wording adaptations, were used to measure bullying perpetration. Children were classified as being exposed to bullying victimization or bullying perpetration if they responded that they had been victimized or had bullied others at least once a month at any time between ages 11 and 13 years. Child maltreatment was measured using the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire Short-Form (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, MacMillan, Trocmé, Jamieson and Boyle2008). Adolescents were contacted at age 19–20 and retrospectively reported on childhood physical and sexual abuse using the stem “How many times before the age of 16 did an adult…” followed by 3 items related to physical abuse and 1-item on sexual abuse. Adolescents who endorsed any of the physical abuse items (no = 0, yes = 1) were classified as being exposed to physical abuse and adolescents who endorsed the sexual abuse item (no = 0, yes = 1) were classified as being exposed to sexual abuse.

Clinical factors . Most clinical symptoms were examined using the Behavior Assessment System for Children-Second Edition (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, Reference Reynolds and Kamphaus2004). The BASC-2 is the gold standard measure for this age group and contains subscales on depression (12 items), generalized anxiety (10 items), hyperactivity (8 items), and somatization (7 items). Items were rated using a 5-point scale (never = 0; very often = 4) or a dichotomous response (false = 0, true = 2). Data on anxiety, depression, and hyperactivity were collected from age 11 and data on somatization were collected from age 13. Item raw scores were summed and transformed into standardized T-scores, with scores of 60 or above being clinically significant (clinical and subclinical symptom levels; Reynolds & Kamphaus, Reference Reynolds and Kamphaus2004). Children with T-scores ≥60 at any time between ages 11 and 13 years were classified as exhibiting clinically significant symptoms of anxiety, depression, somatization, or hyperactivity. Impulsivity was measured by parent-report from age 11 to 13 using the three impulsivity items from the Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Boyle, Hong, Pettingill and Bohaychuk2009). The Brief Child and Family Phone Interview has strong reliability and validity and been normed for parent samples. Items were measured on a 3-point scale (never = 0; often = 2), which were summed and transformed into z-scores. Children with z-scores ≥1 (equivalent to a T-score of 60) at any time between ages 11 and 13 years were classified as exhibiting clinically significant symptoms of impulsivity (Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Boyle, Hong, Pettingill and Bohaychuk2009).

At age 19–20, the M.I.N.I. International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Janavs, Weiller, Keskiner, Schinka, Knapp, Sheehan and Dunbar1997) was administered to participants by a trained postgraduate interviewer to examine diagnosable eating disorders. Adolescents were included in the ED clinical proxy group if they met criteria for any eating disorder (Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, or Binge Eating Disorder). As part of the clinical interview, the Borderline Symptom List (BSL) was also administered (Bohus et al., Reference Bohus, Kleindienst, Limberger, Stieglitz, Domsalla, Chapman, Steil, Philipsen and Wolf2009). Mean score cut-points on the BSL can be transformed into symptom severity classifications, whereby scores >1.5 (high, very high, or extremely high symptoms) separate treatment-seeking BPD patients from clinical and healthy controls (Kleindienst et al., Reference Kleindienst, Jungkunz and Bohus2020). Adolescents were included in the BPD clinical proxy group if they scored >1.5 on the BSL.

Analysis

Missing data patterns between participants included and excluded from the core analytic sample, as well as descriptive data, were examined using a series of independent sample t-tests, chi-square tests (χ2), and Pearson’s correlations in SPSS (IBM version 26). We compared adolescents retained in the sample with those who dropped on variables available at Time 1 (i.e., sex assigned at birth, race/ethnicity, household income, parent education, anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, impulsivity, bullying victimization, and bullying perpetration).

The analyses were performed in several steps that aligned with the research aims. To examine the independent trajectories of disordered eating and BPD features, semiparametric group-based models were estimated in Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017) using latent class growth analysis with full information maximum likelihood estimation to handle missing data. Latent class growth analysis identifies heterogeneity within a sample and classifies individuals based on the probability that they belong to a given class (Nagin, Reference Nagin2005). We tested up to four-class solutions for disordered eating behavior and BPD features separately to identify the number and shape (e.g., linear, quadratic) of distinct trajectories. Evaluation of the best fitting models was based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test, the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test, entropy, and the identification of a conceptually meaningful set of classes (Nylund et al., Reference Nylund, Asparouhov and Muthén2007). We then used the growth parameters from the final trajectory models as the starting values for the joint trajectory model (Haltigan & Vaillancourt, Reference Haltigan and Vaillancourt2014; Vaillancourt & Haltigan, Reference Vaillancourt and Haltigan2018). Conditional probability analyses were run to examine the joint patterning of co-occurring symptoms and the temporal precedence of disordered eating and BPD trajectories. Conditional probability analyses are a standard method of examining temporal precedence in these models (Haltigan & Vaillancourt, Reference Haltigan and Vaillancourt2014; Vaillancourt & Haltigan, Reference Vaillancourt and Haltigan2018).

To examine unique and shared childhood risk factors, we used multinomial logistic regressions on joint class membership. Model 1 included each unadjusted (crude) risk factor. Models 2–4 were partially adjusted for sociodemographic, interpersonal, and clinical risk factors, respectively. To examine the burden of probable clinical cases, we calculated the adjusted population attributable fraction (aPAF) for each modifiable risk factor that remained statistically significant in the adjusted models (Williamson, Reference Williamson2010). Adjusted PAFs are calculated using the following formula:

where PD is the prevalence of exposure among cases (i.e., exposed vs. not exposed) and RRA is relative risk adjusted for confounders. Risk factors were therefore dichotomized into the same metric to compare RRA and calculate PAFs. The highest symptom trajectory classes of disordered eating and BPD features were transformed into binary outcome variables and used as proxies of clinical cases. As a post hoc analysis, we examined whether the adolescent high-risk trajectory classes were adequate proxies for adult clinical cases using binary logistic regressions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to examine whether the high-risk trajectory classes predicted clinically diagnosable ED or BPD in the future.

Results

Missing and descriptive data

Little’s test indicated that data were not Missing Completely at Random, χ 2(375) = 506.709, p < .001. Adolescents who dropped out had lower household income (t = −6.44, df = 615, p < .001), lower parent education (t = 7.70, df = 805, p < .001), were more likely to be non-White (χ2 = 7.23, df = 1, p = .007), and had higher levels of anxiety (t = 2.705, df = 794, p = .007), depression (t = 4.06, df = 694, p < .001), hyperactivity (t = 2.94, df = 718, p = .003), impulsivity (t = 4.33, df = 636, p < .001), bullying victimization (t = 2.26, df = 782, p = .024) and bullying perpetration (t = 2.83, df = 621, p = .005) at Time 1. There were no sex differences in dropout (χ2 = 0.16, df = 1, p = 9.46). Variables had an average of 9.3% missing data (min = 0, max = 20.2).

Mean rates of disordered eating behavior for the total sample gradually increased over time (Table 1), while mean rates of BPD features were stable over time. There were large within-time correlations between disordered eating behavior and BPD features across adolescence (age 14 r = .57, age 15 r = .56, age 16 r = .60, age 17 r = .55, and age 18 r = .51, all ps < .001). Of the total sample, 13.6% identified as LGBTQ+, 15.6% reported physical abuse, 8.4% reported sexual abuse, and 48% reported being bullied. Approximately one in five adolescents reported clinically significant anxiety, depression, or hyperactivity (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

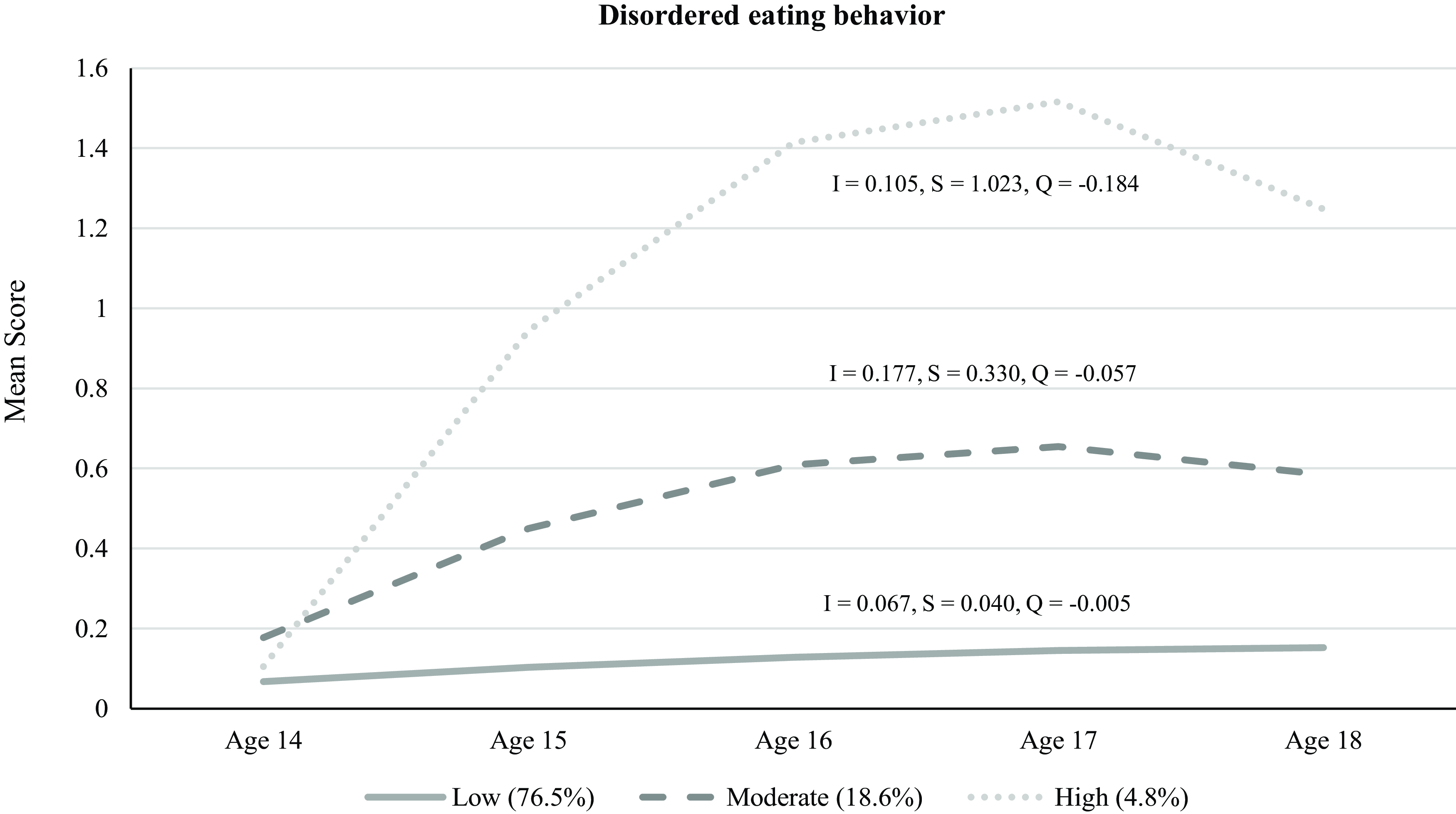

Course of disordered eating behavior

A three-class solution was selected (Figure 1) as it had the lowest BIC value and all other model fit statistics were good (Table 2). Most adolescents followed a stable and low trajectory of disordered eating (n = 418, 77%). The next largest group followed a moderate trajectory (n = 100, 18%), which began low in early adolescence and increased over time (slope = 0.33). The smallest group followed a high trajectory (n = 26, 5%), which began low in early adolescence and rose rapidly in subsequent years (slope = 1.02) peaking at age 17. The posterior probabilities indicated that adolescents were well matched to their trajectory group (.97 for the low group, .90 for the moderate group, and .97 for the high group).

Figure 1. Three-class solution for trajectories of disordered eating behavior.

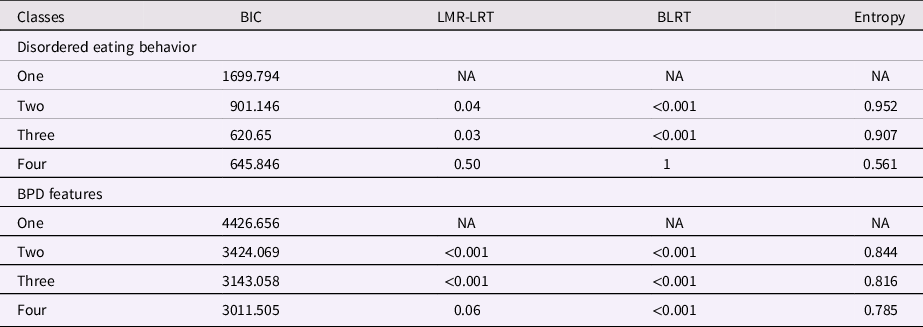

Table 2. Model fit statistics

Note. BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria; LMR-LTR = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test; BLRT = bootstrapped likelihood ratio test.

Course of BPD features

A three-class solution was selected (Figure 2) because although the BIC value was slightly higher than the four-class solution, the other fit indices suggested the three-class solution was more parsimonious (Table 2). The largest group of adolescents followed a stable and moderate trajectory of BPD features (n = 225, 41%). The next largest group followed a stable and low trajectory (n = 204, 38%). The smallest group followed a moderately stable and high trajectory (n = 114, 21%), in which there was a slight increase in symptoms across early adolescence (slope = 0.18) that peaked at age 16. The posterior probabilities indicated that adolescents were well matched to their trajectory group (.94 for the low group, .89 for the moderate group, and .92 for the high group).

Figure 2. Three-class solution for trajectories of features of borderline personality disorder.

Joint trajectories and patterns of comorbidity

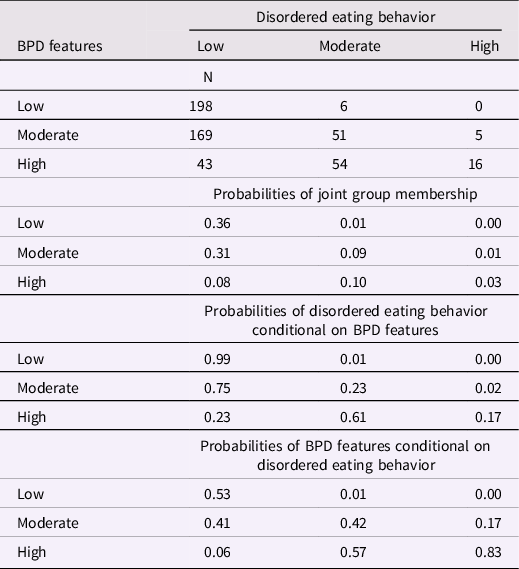

The proportions of adolescents within each joint trajectory group are displayed in Table 3. Although there were nine possible joint trajectories (3 × 3 classes), there were no adolescents in the high disordered eating/low BPD features group. The largest proportion of adolescents reported low disordered eating/low BPD features (healthy group). Almost a quarter of the total sample (23%) had co-occurring symptoms.

Table 3. Joint and conditional probabilities

Temporal precedence of comorbidity

Conditional probability analyses (Table 3) indicated that belonging to the high disordered eating trajectory was a better indicator of belonging to the high BPD features trajectory than was the reverse. That is, there was a high probability (0.83) that adolescents in the high disordered eating trajectory would also be in the high BPD features trajectory, while there was a low probability (0.17) that adolescents in the high BPD features trajectory would also be in the high disordered eating trajectory. The probability that adolescents in the moderate disordered eating trajectory would be in the high BPD features trajectory (0.57) was similar to the probability that adolescents in the moderate BPD features trajectory would be in the high disordered eating trajectory (0.61).

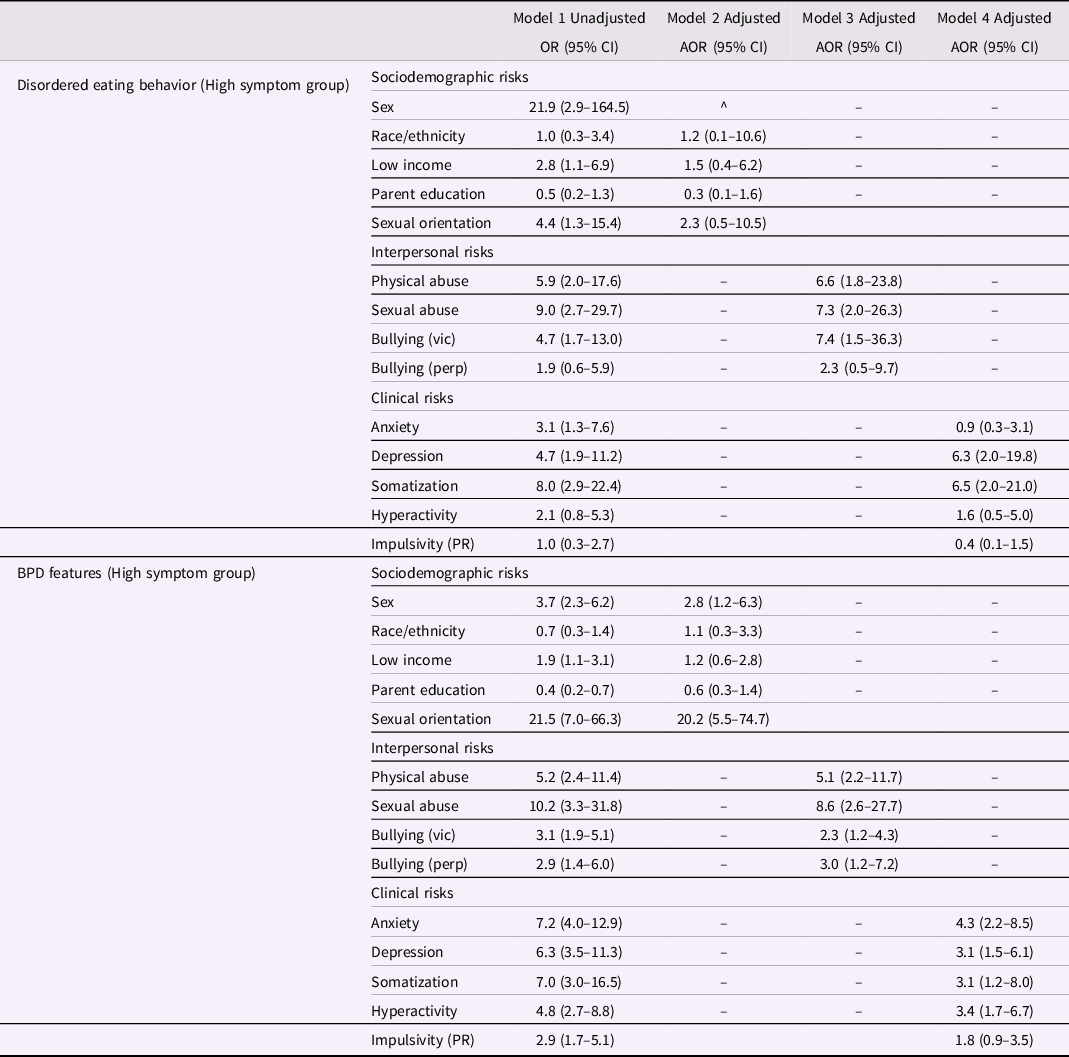

Unique and shared childhood risk factors

Most risk factors were statistically significant in the unadjusted (crude) models (Table 4, Model 1), except for race/ethnicity in the disordered eating and BPD features models, and parent education, bullying perpetration, hyperactivity, and impulsivity in the disordered eating models (see Table 4 for high vs low symptom trajectory groups; all other comparisons are in the supplementary material). Sex (being a girl) was the largest risk factor for belonging to the high disordered eating group (OR = 21.9, 95% CI = 2.9–164.5), while sexual orientation (LGBTQ+) was the largest risk factor for belonging to the high BPD features group (OR = 21.5, 95% CI = 7.0–66.3). In the adjusted models for disordered eating, sex could not be computed because there was only one boy in the high disordered eating trajectory. Most risk factors remained significant and of similar magnitude in the partially adjusted models (Models 2–4) and most risk factors were shared among disordered eating and BPD features. There were no unique risks for disordered eating, but bullying perpetration and hyperactivity were unique risk factors for BPD features.

Table 4. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for high vs low symptom trajectory groups

Note. Model 1 values are the crude estimates for each univariate risk factor; Model 2 estimates are adjusted for sociodemographic risk factors; Model 3 estimates are adjusted for interpersonal risk factors; Model 4 estimates are adjusted for clinical risks factors. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; Vic=victimization; Perp=perpetration; PR = parent-reported. In all models the low symptom trajectory group was used as the reference category.

Population attributable fractions (PAFs)

Adjusted PAFs were estimated for each modifiable risk factor that remained significant in the adjusted models (sex and sexual orientation were not deemed to be modifiable). Under the assumption that adolescents in the high symptom trajectory groups were at risk of becoming clinical cases, the results indicated that eliminating bullying victimization would have the largest impact on incidence reduction; keeping all other exposures constant and eradicating bullying victimization would prevent new cases of eating disorders by 66% and BPD by 37% (see supplementary file for all adjusted PAFs).

Post hoc tests for clinical proxies

The prevalence of clinical eating disorders by age 19–20 was 41.7% among adolescent in the high disordered eating trajectory (vs. 17.8% in the moderate trajectory and 4.8% in the low trajectory). The odds that adolescents in the high disordered eating trajectory would develop a clinical eating disorder was 14 times higher than adolescents in the low disordered eating trajectory (OR = 14.18, 95% CI = 3.96–50.77).

The prevalence of clinical BPD by age 19–20 was 36.8% among adolescent in the high BPD features trajectory (vs. 15.2% in the moderate trajectory and 1.5% in the low trajectory). The odds that adolescents in the high BPD features trajectory would develop clinical BPD was 37 times higher than adolescents in the low BPD features trajectory (OR = 37.21, 95% CI = 8.46–163.64).

Discussion

We examined the course of disordered eating and BPD features, patterns of co-occurrence, temporal precedence, and risk factors across a developmentally sensitive period for the onset of these psychiatric problems. The main findings were that: (a) five percent of adolescents followed a high symptom trajectory of disordered eating, while 21% of adolescents followed a high symptom trajectory for BPD features; (b) almost a quarter of symptomatic youth reported co-occurring disordered eating and BPD features; (c) high levels of disordered eating were a stronger indicator of high levels of BPD features than was the reverse; (d) non-modifiable risk factors were the strongest predictors of belonging to a high trajectory group (girls and LGBTQ+ youth). Most risk factors were shared, but bullying perpetration and hyperactivity were unique to BPD features; and (e) bullying victimization contributed the largest burden to expected clinical cases of eating disorders and BPD.

As the individual trajectories and rates of comorbidity found in this study are in line with previous work (Aimé et al., Reference Aimé, Craig, Pepler, Jiang and Connolly2008; Haltigan & Vaillancourt, Reference Haltigan and Vaillancourt2016a; Martinussen et al., Reference Martinussen, Friborg, Schmierer, Kaiser, Øvergård, Neunhoeffer, Martinsen and Rosenvinge2017), we focus the discussion on the novel findings related to our other aims. First, although prior research has suggested substantial comorbidity between eating disorders and BPD, as replicated in this study with 23% of symptomatic youth reporting co-occurring symptom, there has been a lack of research investigating temporality. For the first time, we found that adolescents can experience high levels of BPD features without engaging in disordered eating behavior, but moderate or high levels of disordered eating were associated with moderate or high levels of BPD features. This finding mirrors research showing that disordered eating precedes depression (Lee & Vaillancourt, Reference Lee and Vaillancourt2018) and fits broadly with the field of nutritional psychiatry (Marx et al., Reference Marx, Moseley, Berk and Jacka2017). Disordered eating may also be an indicator of self-harm or self-neglect that precipitates other symptoms of psychopathology. Compromised eating behavior thus plays a nonignorable role in mental health. The clinical implications are that interventions targeting disordered eating may inhibit the development of comorbid psychopathology. This warrants further investigation.

Second, girls were at the largest risk for high levels of disordered eating behavior, while LGBTQ+ youth were at the largest risk for high levels of BPD features. Regarding disordered eating, our results corroborate prior research showing that girls engage in more pathological eating behavior than boys (Croll et al., Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Ireland2002; Micali et al., Reference Micali, Ploubidis, De Stavola, Simonoff and Treasure2014), but we are cognizant that we were likely underpowered to detect effects among boys. Likewise, our results align with cross-sectional research showing that LGBTQ+ status confers risk for BPD, above and beyond sex assigned at birth, anxiety, and depression (Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Sharp, Kalpakci, Choi and Temple2016). To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to show that LGBTQ+ adolescents are at risk of fitting a profile of high BPD features longitudinally. Adolescence is a time of identity formation, which may explain why we found a higher proportion of adolescents with BPD features in this sample (21%) than has been found among university samples (9.7%; Meaney et al., Reference Meaney, Hasking and Reupert2016). LGBTQ+ youth may experience unique difficulties in identity formation in the face of invalidating environments and the enduring stigmatization of sexual orientations that deviate from heterosexual. Because we used a blunt characterization of sex (boy vs. girls) and sexual orientation (heterosexual vs. LGBTQ+), further research is needed to identify patterns for specific sexual and gender orientations and to examine the social and neurobiological mechanisms that link gender and sexuality to disordered eating and BPD features. Further research is also needed to examine risk factors for intersectional identities, as we were underpowered to test for these potential interactions.

Third, most risk factors were shared, but there were two unique childhood risk factors for high levels of BPD features: clinically significant hyperactivity and bullying perpetration. Although the overlap between ADHD and BPD is well documented (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall, Krygsman, Boylan, Duku and Hymel2014; Winsper et al., Reference Winsper, Hall, Strauss and Wolke2017), questions remain as to whether ADHD and BPD are the same disorder in different stages of development (Gomes Cano et al., Reference Gomes Cano, Pires and Serrano2017) or whether they are different disorders with shared etiology, with early regulatory problems being one potential pathway (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall, Krygsman, Boylan, Duku and Hymel2014; Winsper et al., Reference Winsper, Hall, Strauss and Wolke2017). Although bullying perpetration was a unique risk factor, bullying perpetration and victimization often co-occur (Haltigan & Vaillancourt, Reference Haltigan and Vaillancourt2014; Lereya et al., Reference Lereya, Copeland, Zammit and Wolke2015), and prior research has shown that childhood bullying victimization is a risk factor for probable BPD (Wolke et al., Reference Wolke, Schreier, Zanarini and Winsper2012). Developmentally sensitive research on the precise mechanisms that result in divergent pathways to BPD and eating disorders is therefore needed. The non-specific effects of the other sociodemographic, interpersonal, and clinical risk factors align with the principles of equifinality and multifinality (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996) and may explain the high levels of co-occurring symptoms.

Fourth, this is the first study to examine population attributable fractions in relation to disordered eating. We included a broad range of the most common and largest risk factors, but we were unable to examine all risks common to ED and BPD, such as genetic predisposition, gene–environment interactions, neglect, emotional abuse, or sleep problems (Amad et al., Reference Amad, Ramoz, Thomas, Jardri and Gorwood2014; Morales-Muñoz et al., Reference Morales-Muñoz, Durdurak, Bilgin, Marwaha and Winsper2021; Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Stubbs, Ricca, Moretti, Busatta, Carvalho, Dragioti, Favaro, Monteleone, Shin, Fusar-Poli and Castellini2021; Winsper et al., Reference Winsper, Lereya, Marwaha, Thompson, Eyden and Singh2016; Yilmaz et al., Reference Yilmaz, Hardaway and Bulik2015). In this study, childhood physical and sexual abuse were the largest interpersonal risk factors for BPD and bullying victimization was the largest interpersonal risk factor for disordered eating. The higher prevalence of bullying victimization in comparison to child maltreatment meant that expected clinical cases of eating disorder and BPD could be reduced the most by eradicating bullying. A study of large population-based cohorts from the United States and United Kingdom has similarly shown that being bullied in childhood is a stronger risk factor for internalizing problems than child maltreatment (Lereya et al., Reference Lereya, Copeland, Costello and Wolke2015), while other research has shown that bullying and physical abuse have similar effects on mental health (Lee & Vaillancourt, Reference Lee and Vaillancourt2019b). The bullying measure used in this study examined general bullying, however, prior work has shown that bullying victims do receive more negative feedback about their appearance, which likely increases the risk of disordered eating (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Dale, Guy and Wolke2018). The strikingly high PAFs observed in this study mean that coordinated efforts to intervene early in childhood bullying remain a priority.

Despite the merits of our study, including the prospective design and the person-centered approach, it is not without limitations. Notably, we were unable to compare all levels of symptom co-occurrence because of relatively small numbers and thus low power within some of the trajectory groups. Further research is needed to determine whether risk factors are differentially associated with varying levels of comorbidity. As is typical in longitudinal research, there was participant attrition (9.3%). We accounted for missing data using the full information maximum likelihood estimation estimator, which has equivalent performance to multiple imputation (Lee & Shi, Reference Lee and Shi2021). However, as missing data were systematic, we cannot conclude that the results are representative of our randomly sampled population. The analytic sample consisted of adolescents with higher household income and parental education, lower levels of mental health morbidities, and lower levels of bullying victimization and perpetration. As highly vulnerable adolescents were therefore most likely to drop out, the effect sizes may be larger than reported here. Our sample was also mostly white, and although this is reflective of the Canadian population (http://www.statscan. gc.ca), further large-scale and well-powered studies are needed to examine intersectionality (e.g., race/ethnicity and LGBTQ+). We used a composite measure of disordered eating, which did not allow us to test associations between BPD features and disorder-specific eating pathologies such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge eating disorder. However, the composite allowed us to overcome issues associated with female-centric and thinness-orientated (anorexia, bulimia) classifications (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Nagata, Griffiths, Calzo, Brown, Mitchison, Blashill and Mond2017) and to account for diagnostic instability, Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorders, and subclinical symptomology. Our measure is also unique because it focuses on eating disorder behavior and not thoughts, which are normative and overrepresented in community samples of girls (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Vaillancourt and Hanna2009). Most of our measures were self-reports, which can inflate effect sizes because of shared method variance, although our inclusion of parent-reported data and the longitudinal design helped to mitigate some of this bias. Last, the implications and generalizations that can be drawn from the data are limited by the equivocal link between symptoms and disorders. However, in our post hoc analyses, we found that almost half of adolescents in the high disordered eating trajectory and over a third of adolescents in the high BPD features trajectory met the criteria for a clinical disorder by age 19–20. As subclinical symptoms are common and debilitating (Micali et al., Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy, Calzo, Sonneville, Swanson and Field2015; Schaumberg et al., Reference Schaumberg, Jangmo, Thornton, Birgegård, Almqvist, Norring, Larsson and Bulik2018; Zanarini et al., Reference Zanarini, Reichman, Frankenburg, Reich and Fitzmaurice2010), and most mental health problems remain undiagnosed and untreated (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Angermeyer, Borges, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, de Graaf, Gureje, Haro, Karam, Kessler, Kovess, Lane, Lee, Levinson, Ono, Petukhova and Wells2007), the measurement of symptoms in community samples remains valuable and important.

Notwithstanding the above limitations, this is the first study to systematically examine the joint trajectories, comorbidity, and unique risk factors for adolescent eating disorders and BPD – two of the most serious and enduring psychiatric illnesses – and we make several new contributions to knowledge. Although girls and LGBTQ+ youth fit profiles of high vulnerability, bullying prevention efforts could notably reduce eating and BPD pathology. Research into the early treatment of eating problems warrants further investigation, and the assessment of sexual orientation may be valuable when screening for BPD in young people.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579423000792.

Availability of data and material

Data available on request.

Code availability

Code available on request.

Funding statement

This research was supported by Grants 833-2004-1019 and 435-2016-1251 from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Grants 201009MOP-232632-CHI-CECA-136591 and 201603PJT-365626-PJT-CECA-136591 from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, and the Grant PA-13-303 from the Ontario Mental Health Foundation.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Ethical standard

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All persons gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.