INTRODUCTION

Multinational corporations (MNCs) from developed economies play a major role in contributing knowledge, transferring technology, and increasing income and employment in the host emerging economies in which they operate (Almeida & Phene, Reference Almeida and Phene2004; Kogut & Chang, Reference Kogut and Chang1991). Emerging economies exhibit high growth yet lack the sophisticated institutional framework seen in developed economies (Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Obloj, Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Obloj2008; Khanna & Palepu, Reference Khanna and Palepu1997; Meyer & Tran, Reference Meyer and Tran2006). Vietnam, the focus of the present study, is one such economy. It has transitioned from a centrally planned economy to a market economy, and from a poor country heavily damaged by multiple wars to a lower-middle-income country (Christens & Kirshner, Reference Christens and Kirshner2011). It has recently become one of the fastest-growing star markets in South East Asia (Sickle, Reference Sickle2020; Vanham, Reference Vanham2018). By the mid to late 1990s, as a result of the ‘open door’ policy adopted by the Vietnamese government, numerous MNCs expanded their businesses into Vietnam through a number of foreign direct investment (FDI) projects – of which there were five times as many in 2000 as there were in 2007 (Ni, Spatareanu, Manole, Otsuki, & Yamada, Reference Ni, Spatareanu, Manole, Otsuki and Yamada2017; Yang, Reference Yang2019). The frequency with which MNCs have entered Vietnam over the past decades has, in part, been driven by opportunities arising from its market's sheer size and, until recently, impressive economic and population growth. With a population of over 90 million people and a market larger than that of several European countries, Vietnam's demographics are considered more favorable than those of China (Alam, 2020; Ni et al., Reference Ni, Spatareanu, Manole, Otsuki and Yamada2017). Vietnam's per capita income has more than quadrupled since the 1990s (GSO, 2014, 2015, 2018), its economic growth is 6–7% higher than China's, and almost 75% of the population are aged between 15 and 64. A fast-growing middle class and low labor costs make Vietnam an attractive proposition for MNCs, especially those who have recently made a strategic move to the country due to the current China–USA trade war (Jennings, Reference Jennings2019; Leng, Reference Leng2019; Reed & Romei, Reference Reed and Romei2019). The country has also coped well with the COVID-19 crisis (Alam, 2020; Sickle, Reference Sickle2020).

Numerous host country nationals (HCNs) seek employment with MNCs, typically because of relatively high pay and the opportunity to gain new knowledge and learn new skills. Overall, 1/3 of the country's labor force has worked for MNCs, growing from 330,000 in 1995 to 1.5 million in 2007, to 4 million in 2014 (MOLISA, 2015; Tran, Reference Tran2018). However, by the end of 2010, this trend was surprisingly reversed, with most HCNs leaving to establish their own businesses, having worked for these MNCs for some time (GSO, 2015; Viettonkin Consulting, 2019). A survey by the Topica Founder Institute in 2016 reported that 78% of people founding successful start-ups used to be MNC employees, 48% of whom used to work for foreign companies (Topica Founder Institute, 2016). Given the advanced working conditions, excellent learning opportunities, and substantially higher compensation compared to what domestic firms offer, this raises two questions: why do HCNs leave their MNC jobs to create their own ventures, and how do they achieve this?

The literature on HCNs typically assumes that HCNs stay as HCNs (Collings & Scullion, Reference Collings, Scullion, Scullion and Collings2006; Fee & Michailova, 2019; Harzing, Reference Harzing2001a, Reference Harzing2001b). HCNs in less developed countries are often viewed as lucky, fortunate, and/or privileged to work for MNCs from developed countries and are therefore not typically expected to quit their MNC jobs and create new ventures. Although several studies have examined expatriate entrepreneurship (Selmer, McNulty, Lauring, & Vance, Reference Selmer, Mcnulty, Lauring and Vance2018; Vance, McNulty, Paik, & D'Mello, Reference Vance, McNulty, Paik and D'Mello2016), few, if none, have recognized the phenomenon of HCN entrepreneurship. The entrepreneurship literature on employees leaving jobs to become entrepreneurs has predominantly focused on developed markets and manufacturing industries where institutions are less volatile. Such studies have generally examined dimensions of entrepreneurship with regard to motivation, decision-making, and regulatory focus, typically in spin-offs in high-tech industries and mainly for patent commercialization (Folta, Delmar, & Wennberg, Reference Folta, Delmar and Wennberg2010; Klepper, Reference Klepper2001). Little is known about this phenomenon in relation to HCNs and service industries in emerging markets such as Vietnam. This lack of insight is particularly regrettable as Vietnam's institutional context offers an exciting avenue for research: it both affords entrepreneurial opportunities and exhibits substantial institutional voids, leading to idiosyncratic forms and types of entrepreneurship.

Several scholars have highlighted the need for a deeper understanding of emerging markets as a context for entrepreneurial phenomena (Bruton et al., Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Obloj2008; Kiss, Danis, & Cavusgil, Reference Kiss, Danis and Cavusgil2012). Although emerging markets are becoming more important with regard to growth patterns and entrepreneurial activity (Bruton et al., Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Obloj2008; Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Puky, Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Puky2009; Peng & Meyer, Reference Peng and Meyer2011), they also exhibit significant institutional differences that have resulted in different forms and types of entrepreneurship (Webb, Khoury, & Hitt, Reference Webb, Khoury and Hitt2020). However, studies have not scrutinized the fact that in the absence of well-enforced institutions, new types of businesses can be founded by employees who used to work for MNCs. In the context of changing institutions, MNCs ignite the growth of local emerging economies where they operate through HCN entrepreneurship. This type of entrepreneurship has contributed to unleashing entrepreneurial energy and fueling growth in previously state-dominated economies.

The HCN-founded ventures also play a vital role as a major route through which knowledge spillovers occur and jobs are created (Agarwal, Ganco, & Ziedonis, Reference Agarwal, Ganco and Ziedonis2009; Bruton et al., Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Obloj2008; Meyer & Sinani, Reference Meyer and Sinani2009). Knowledge spillovers via the HCN entrepreneurship route arise from non-market transactions when knowledge resources are disseminated without a contractual relationship between the knowledge owner and recipient. However, the nature of such spillovers and how they emerge have not been examined in great detail from an entrepreneurship perspective; indeed, most of the findings in this area are concerned with macroeconomic relationships between FDI and economic growth. There are limited insights into the reasons why HCNs leave MNCs and become entrepreneurs, as well as the different paths they follow when deciding to establish their ventures. Given the dearth of knowledge on entrepreneurial ventures founded by HCNs in emerging economies, the research question we posed is: Why and how do HCNs exit the MNCs that employ them to become entrepreneurs?

Emerging market research has been criticized for its heavy reliance on existing questions, theories, constructs, and methods developed in the Western context (Jia, You, & Du, Reference Jia, You and Du2012; Plakoyiannaki, Wei, & Prashantham, Reference Plakoyiannaki, Wei and Prashantham2019; White, Reference White2002). To counter this, we adopted a phenomenon-based approach, allowing us to avoid such theoretical constraints and identify the puzzling issues that may emerge from case observations in a Vietnamese context (Davies, Reference Davies2006; Hambrick, Reference Hambrick2007; Kharuna, Reference Kharuna2007; von Krogh, Rossi-Lamastra, & Haefliger, Reference Von Krogh, Rossi-Lamastra and Haefliger2012). We began our process of inquiry by observing and then identifying and describing salient aspects of the entrepreneurial journey undertaken by Vietnamese HCNs who left their MNC employer to set up their business. Our fieldwork took place in 2015, 2017, and 2018 and found that the key reasons for becoming an entrepreneur are contextually driven rather than purely individually motivated, and include the following: (1) seize new local market opportunities created by MNCs themselves, (2) utilize advanced professional knowledge and skills acquired while working in an MNC, and (3) address work-life balance issues and limited options for career progress within MNCs. We were able to identify four different migration pathways HCNs tended to follow once they decided to leave the MNC: MNC returnees, transitional hybrids, committed hybrids, and direct spin-offs. We found that the transitional hybrid and committed hybrid pathways operate ‘under cover’ and are only made possible due to institutional voids.

Our article contributes to the employee entrepreneurship literature by exploring HCNs leaving MNCs in emerging markets for reasons idiosyncratic to the contrasting working conditions of MNCs and local firms. The key motivational factors that drive new ventures and the four paths we have identified differ from the prevailing literature on employee entrepreneurship facilitated by the absence of regulated and well-enforced institutions. Contrary to the literature on HCNs, our findings suggest that the typical view that HCNs typically continue to work for MNCs should be questioned. HCNs amount to so much more than being local employees who are merely there to support expatriates sent by the headquarters. Nor is their acquisition of knowledge and expertise merely a contribution to the development of the local subsidiary and, ultimately, the MNC. HCNs develop their own strategies while working for the MNC and, at a suitable time, prefer to exit and become entrepreneurs. Our study has implications for local governments in promoting local entrepreneurship and attracting well-trained talent. MNCs should also be aware that the HCNs who work for them can become their competitors.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. In the next section, we briefly outline existing research in the two streams of literature, HCNs and employee entrepreneurship, that form our study's conceptual background. This is followed by an explanation and justification for the methodological choices adopted and the fieldwork conducted. We then present our analysis and findings. Finally, we conclude and outline the key theoretical and practical implications of our study.

CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND

Host Country Nationals in MNCs

The literature on HCNs predominantly adopts an MNC- or expatriate-centered perspective. Discussion regarding HCNs centers around exploiting local advantages through knowledge sharing (Heizmann, Fee, & Gray, Reference Heizmann, Fee and Gray2018), staffing (Collings & Scullion, Reference Collings, Scullion, Scullion and Collings2006; Collings, Morley, & Gunnigle, Reference Collings, Morley and Gunnigle2008), compensation (Bonache, Sanchez, & Zárraga-Oberty, Reference Bonache, Sanchez and Zárraga-Oberty2009), and career progression (Vo, 2019) to facilitate MNCs’ international operation or support expatriates in the host countries. Because HCNs are familiar with the cultural, economic, political, and legal environment of the host country, they bring valuable local knowledge of the market and business practices (Harzing, Reference Harzing2001a) to both the headquarters and the subsidiary, thus decreasing the liability of foreignness among MNCs in the host country. It is, therefore, mainly because of HCNs that MNCs can react and respond better to the requirements, demands, and preferences of the host country. For instance, HCNs can easily address local idiosyncrasies associated with the specificities of the local environment (Fee & Michailova, Reference Fee and Michailova2020; Harzing, Reference Harzing2001b). HCNs are also the preferred subsidiary employees when local knowledge is more valuable than expatriates’ managerial and functional knowledge (Harzing, Reference Harzing2001b; Michailova, Mustaffa, & Barner-Rasmussen, Reference Michailova, Mustaffa and Barner-Rasmussen2016). Staffing by expatriates leads to escalating relocation overheads and administrative costs; and the headquarters fear failure or under-performing expatriates because of the long process of adjustment to the host country environment (Collings & Scullion, Reference Collings, Scullion, Scullion and Collings2006; Harzing, Reference Harzing2001a). The employment of HCNs, especially in key positions, is better received by host governments as it tends to be interpreted as a sign of an MNC's commitment to the host country (Selmer, Reference Selmer2004). Employing HCNs in visible subsidiary positions also indicates that an MNC is committed to developing their careers (Collings & Scullion, Reference Collings, Scullion, Scullion and Collings2006).

MNCs tend to deploy more HCNs in industries and functional areas where localization is more important than coordination and control (Putti, Singh, & Stoever, Reference Putti, Singh and Stoever1993). Therefore, especially in the service sector, MNCs often rely on hiring HCNs and making use of their locally-specific knowledge as well as their sensitivity to local demands and changing market conditions (Ando, Reference Ando2015; Ando & Endo, Reference Ando and Endo2013; Beamish & Inkpen, Reference Beamish and Inkpen1998). A vital part of this knowledge lies in HCNs’ familiarity with the way formal and informal institutions in the host country work (or not) and how institutional challenges can be overcome. This has been found to help establish effective relationships and reduce tensions and conflicts between the MNC and local entities (Ando, Reference Ando2015; Ando & Paik, Reference Ando and Paik2013). Therefore, hiring HCNs is an efficient way for MNCs to establish and promote the legitimacy of the company (Putti et al., Reference Putti, Singh and Stoever1993).

The HCN literature has offered some explanations for why some HCNs would consider leaving the MNC. Reiche (Reference Reiche2007), albeit in a different context, argues that existing literature reflects the view that ‘a huge number of foreign expatriates block HCNs’ career advancement opportunities and create sizeable income and status disparities, leading to frustration and dissatisfaction among locals’ (526). Another, somewhat related, reason is that HCNs are more likely to start and/or develop their careers with MNCs at the subsidiary in the host country (Tan & Mahoney, Reference Tan and Mahoney2006). Compared with expatriates and third country nationals, HCNs often occupy lower positions in the hierarchy (Michailova et al., Reference Michailova, Mustaffa and Barner-Rasmussen2016). However, these studies do not reveal what the HCNs ultimately do if they are frustrated in their career development; whether they stay or leave, and, if the latter, where they go. We address this by investigating HCNs leaving MNCs to set up their own business.

Employee Entrepreneurship: A Brief Review and Specificities in Emerging Economies

Employee entrepreneurship refers to employees who leave their jobs and start ventures in the same industry as their employer organizations (Agarwal, Echambadi, Franco, & Sarkar, Reference Agarwal, Echambadi, Franco and Sarkar2004; Franco, Reference Franco, Alvarez, Agarwal and Sorenson2005; Klepper, Reference Klepper2001), including individuals who develop a business idea during their paid employment (Bosma et al., Reference Bosma, Wennekers, Guerrero, Amorós, Martiarena and Singer2013). Current research has investigated the factors that motivate employees to quit and engage in entrepreneurial activity. These include a lack of attention and credible commitment by the former employer, contracts on entrepreneurial rents that are not enforceable, exhaustion of learning and career possibilities, or simply frustration (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Echambadi, Franco and Sarkar2004; Anton & Yao, Reference Anton and Yao1995; Burton, Sørensen, & Beckman, Reference Burton, Sørensen and Beckman2002; Gans & Stern, Reference Gans and Stern2003; Hellmann, Reference Hellmann2007; Klepper & Thompson, Reference Klepper and Thompson2010). Another substantial body of literature focuses on how the spillover and transfer of knowledge from previous employers affect new employee-founded firms' performance. In this stream of research, previous employer organizations act as contexts that define the types and characteristics of the knowledge, resources, and assets that are transferred to new firms. For instance, the transfer of knowledge and resources has been explored under the effects of either weak appropriability regimes (Campbell, Ganco, Franco, & Agarwal, Reference Campbell, Ganco, Franco and Agarwal2012; Carnahan, Agarwal, Campbell, & Franco, Reference Carnahan, Agarwal, Campbell and Franco2010; Garvin, Reference Garvin1983; Phillips, Reference Phillips2002; Simons & Roberts, Reference Simons and Roberts2008; Wenting, Reference Wenting2008) or strong appropriability regimes (Chatterji, Reference Chatterji2009; Ganco, Reference Ganco2013; Stuart & Sorenson, Reference Stuart and Sorenson2003a, Reference Stuart and Sorenson2003b) as well as in relation to the success, size, and age of the employer organizations (Phillips, Reference Phillips2002; Sørensen & Phillips, Reference Sørensen and Phillips2011)

The literature also highlights two main ways individuals can engage in employee entrepreneurship outside current employment contracts: hybrid-entrepreneurship and spin-offs. The former refers to the state of being active as an entrepreneur outside an existing employment contract (Burke, FitzRoy, & Nolan, Reference Burke, FitzRoy and Nolan2008; Burmeister-Lamp, Lévesque, & Schade, Reference Burmeister-Lamp, Lévesque and Schade2012; Folta et al., Reference Folta, Delmar and Wennberg2010; Petrova, Reference Petrova2012; Wennberg, Folta, & Delmar, Reference Wennberg, Folta and Delmar2006). Empirical work emphasizes the initiation of ventures (Folta et al., Reference Folta, Delmar and Wennberg2010) while simultaneously working for wages. Burmeister-Lamp et al. (Reference Burmeister-Lamp, Lévesque and Schade2012) focus on how hybrid entrepreneurs make decisions enabling them to allocate their time between entrepreneurial and employment-related activity. On the other hand, spin-offs are companies founded by the employees of incumbent firms after they have ceded their employment contracts (Klepper, Reference Klepper2001). Several factors are known to influence the survival of new ventures. For instance, Agarwal et al. (Reference Agarwal, Echambadi, Franco and Sarkar2004) argue that the quality of parent knowledge at the point of separation influences the sustainability of a spin-off: better knowledge eases the absorption of new knowledge about markets and how to serve them, as well as knowledge of technology and managerial processes (Shane, Reference Shane2003). The chances of a spin-off surviving have also been found to increase with higher levels of employment and a greater variety of positions held in previous jobs (Helfat & Lieberman, Reference Helfat and Lieberman2002). The literature on spin-offs indicates there is a logical nexus between the prior knowledge of founders and the survival of new ventures in the same industry.

However, the extant employee entrepreneurship literature does not offer an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon in the context of emerging economies. For instance, although the literature on hybrid entrepreneurship highlights the motivation to pursue employee entrepreneurship outside current employment contracts, no insights exist in relation to HCNs in this context. Conversely, most of the empirical research on spin-off survival has been conducted in traditional manufacturing industries as well as high tech industries in developed markets. Other than a series of studies on returnee entrepreneurship in China that are built upon knowledge spillover theory and human mobility (Liu, Lu, & Choi, Reference Liu, Lu and Choi2014; Liu, Wright, & Filatotchev, Reference Liu, Wright and Filatotchev2015; Liu, Lu, Filatotchev, Buck, & Wright, Reference Liu, Lu, Filatotchev, Buck and Wright2010; Liu, Wright, Filatotchev, Dai, & Lu, Reference Liu, Wright, Filatotchev, Dai and Lu2010), little is known about how the transition of employees to entrepreneurship is affected by the unique characteristics of other emerging economies in Asia in the context of MNCs. Emerging markets are characterized as high growth, large markets but with institutional voids that do not support stable, efficient, and effective economic activities and entrepreneurship (Bruton et al., Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Obloj2008; Bruton et al., Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Puky2009; Henry & Welch, 2016; Meyer & Tran, Reference Meyer and Tran2006; Ni et al., Reference Ni, Spatareanu, Manole, Otsuki and Yamada2017; Peng & Meyer, Reference Peng and Meyer2011; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Khoury and Hitt2020). It is unclear whether the absence of well-regulated institutions would support or constrain enterprise pursuit (Khoury & Prasad, 2016; Light & Dana, 2013; Mair, Martí, & Ventresca, Reference Mair, Martí and Ventresca2012), particularly in the context of employee entrepreneurship.

In summary, although a considerable amount of generic knowledge exists about employee entrepreneurship, less is known about HCN employees leaving MNCs to become entrepreneurs in the context of emerging markets. Why they leave, the pathways they choose to optimize their circumstances, and the characteristics of the emerging markets that make this transition process idiosyncratic are key questions that need to be addressed. The present article aims to answer these questions. In so doing, we deepen the understanding of MNCs’ role in promoting local entrepreneurship in emerging markets. We also provide valuable input for MNCs in terms of raising their awareness of the trade-off between benefits and brain drain when dealing with HCNs. In the next section, we explain how the present study was conducted to achieve these objectives.

METHODS

Phenomenon-Based Approach: How Fieldwork Changed the Initial Aim of Our Inquiry

One of our research team members previously worked in an MNC in Vietnam and then left to study abroad. When she returned, she found that most of her colleagues, family members, and friends who had worked for MNCs had quit their jobs and established their own businesses in sectors similar to those of their former MNC employers or in supplementary (supplying or contracting) industries. Most newly established ventures provide professional services, probably because of the relatively low capital investment needed to set them up. These HCN entrepreneurs brought the professional knowledge and skills they had acquired while working for the MNC to their new ventures and the social networks they had established and cultivated, including government and MNC contacts. Some entrepreneurial ventures grew into large businesses and expanded internationally; others eventually failed.

Intrigued by this phenomenon and the lack of research that explains what had occurred, we decided to explore this more thoroughly. Because only a limited body of research exists linking the literature on HCNs with employee entrepreneurship perspectives in general and emerging economies in particular, a phenomenon-based approach was deemed most appropriate (Cheng, Reference Cheng2007; Hambrick, Reference Hambrick2007; von Krogh et al., Reference Von Krogh, Rossi-Lamastra and Haefliger2012). Although we invoke two streams of literature, we began our inductive study, unaware of whether this literature would either resemble or differ from our findings. Phenomena are defined ‘as regularities that are unexpected, that challenge existing knowledge (including the extant theory) and that are relevant to scientific discourse’ (von Krogh et al., Reference Von Krogh, Rossi-Lamastra and Haefliger2012). Thus, the aim of our phenomenon-based research was to capture, describe, and document, as well as conceptualize, a phenomenon so that appropriate theorizing and the development of research designs can proceed at a later stage or in a different/subsequent study. We subscribe to Hambrick's argument (Reference Hambrick2007: 1346) that too strong a focus on theory is likely to ‘prevent the reporting of rich details about interesting phenomena for which no theory yet exists’. We began with a broadly scoped inquiry and remained flexible about our focus. We kept an open mind and worked with various questions, including what motivated HCNs to become entrepreneurs, why some new businesses founded by HCNs survived and grew while others were short-lived, and what factors were responsible for the success and failure of such ventures.

Sampling and Interviewing

We applied for and received funding from one of our universities to conduct fieldwork for the research, entitled ‘Employee spin-offs from MNCs in emerging markets: The case of Vietnam’. We were interested in HCN entrepreneurs who had previously worked for MNCs and survived in the new business they had launched. We chose to sample the service sector because this was the sector in which MNCs’ entry was most commonly observed. It was also more common for HCNs to create a new business in this sector as there were fewer entry requirements. We specified three inclusion criteria. The venture had to: (1) be established by former or current HCNs; (2) have a minimum of three years of survival (except for MNC returnees); and (3) operate in the professional service sector. We identified and interviewed 30 HCNs who satisfied all three criteria. The fieldwork began in 2015 and continued for three months. After initial data collection and analysis, we undertook further in-depth fieldwork in 2017 and 2018. Semi-structured interviews were at the heart of our fieldwork.

We began by adopting a naturalistic inquiry approach, which allowed us to engage physically and psychologically with the study's context. We stayed in direct contact with participants and therefore obtained in-depth accounts of the field (Plakoyiannaki et al., Reference Plakoyiannaki, Wei and Prashantham2019). We conducted each interview with an open mind as we wanted to explore the phenomenon rather than test any pre-defined predictions. We stayed alert to potential new issues, stories, and patterns that emerged as we continued the data collection. We treated each HCN's story as a case study that represented a new venture that they had started, with a retrospective view on what happened to them and their company. We took an open approach to interviewing by letting the participants tell us about their career stories and noting any critical events that took place along the journeys they described. We consistently asked them why they did what they did and how their story had unfolded.

After 20 interviews, we realized that most of our research participants wanted to converse primarily on two issues: why they became entrepreneurs and how they achieved this. At this point, we decided these two issues would become the two elements of our research question. Through recursive recycling, the use of replication logic, and by comparing interview transcripts (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007), we began to see how certain motivations to start a new venture were associated with a particular way of establishing this venture and the factors underpinning its success. We also started to identify distinctive patterns of migration that were surprisingly different from those established in both the HCN and the employee entrepreneurship literature. We began to realize that each migration pathway was characterized by a certain set of specificities not shared by other pathways.

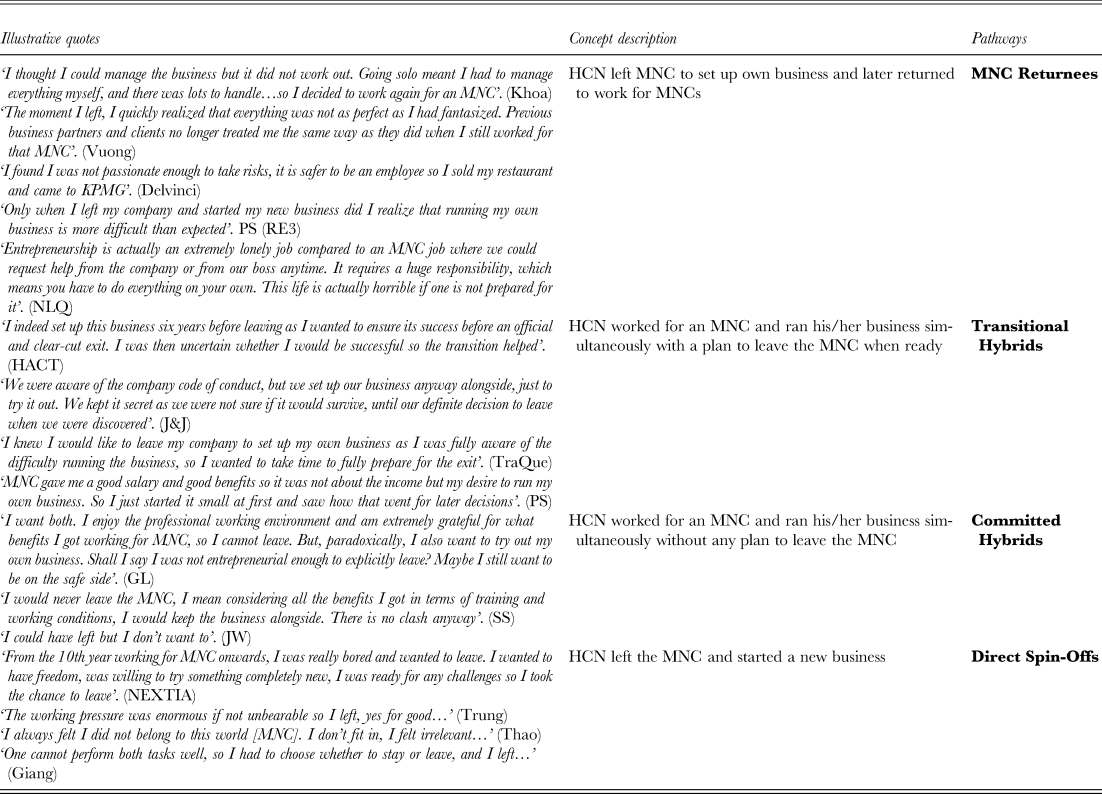

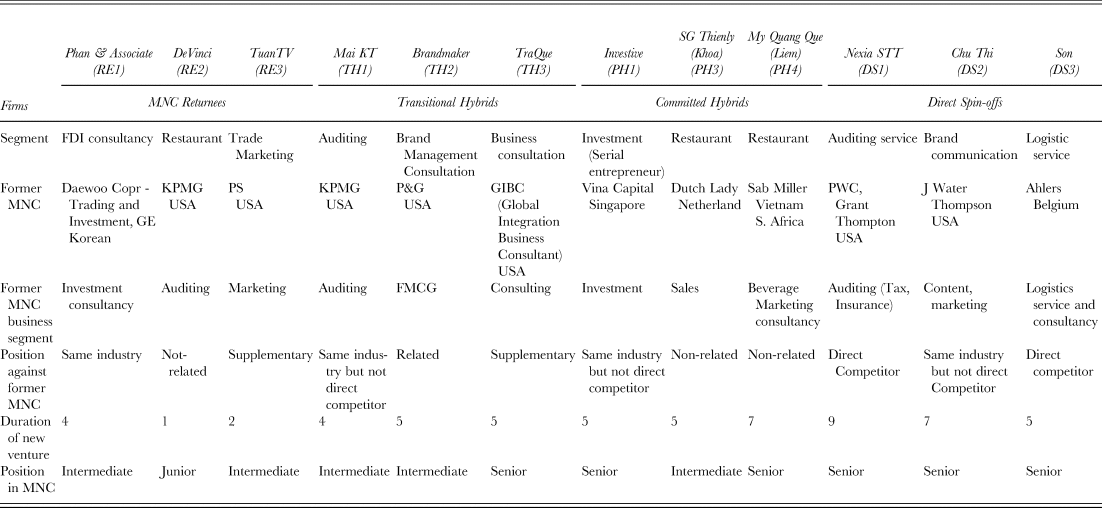

After identifying the pathways from a large sample (see Table 1 for illustrative quotes for each pathway), we decided to include 12 cases in our final sample for further in-depth exploration, with three cases representing each pathway. The cases were theoretically sampled because they were particularly suitable for understanding the phenomenon of HCNs’ entrepreneurial journey and can provide the answer to our research questions (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007; Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1998). Our criteria for retaining these 12 cases were duration of around 5–10 years for each new venture to ensure a stable pathway had been established (except for the case of MNC returnees where a period of 1-year survival was deemed sufficient). As summarized in Table 2, the sample was mixed, with varying levels of seniority, working experience, sectors, and the associations between previous MNC sectors and new businesses. Some HCNs worked for service firms but opened a product-related business, while others worked for manufacturing industries but in a trade marketing and consultancy capacity. All qualified for our sample as being service-related.

Table 1. From HCNs to entrepreneurs: Identification of four key pathways and illustrative quotes

Table 2. Cases and their key characteristics

Two research team members conducted interviews with HCNs-turned-entrepreneurs in the three largest cities in Vietnam: Ha Noi, Ho Chi Minh, and Danang. Each interview lasted 45–90 minutes. The interviews commenced with a series of open-ended questions to explore how HCNs transitioned into becoming entrepreneurs, how they switched between an employee and an entrepreneur role, and what particular pathway they followed and why. We also arranged follow-up interviews via phone or through an exchange of emails when the information from the first interviews was unclear or inconsistent with what we had learned from later interviewees. Interviews were conducted in the Vietnamese language by two native-speaking researchers with an in-depth knowledge of the local context (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Tsui-Auch, Yang, Wang, Chen and Wang2019; Outila, Piekkari, & Mihailova, Reference Outila, Piekkari and Mihailova2019; Win & Kofinas, Reference Win and Kofinas2019). This meant that only a selection of interviews were back-translated from Vietnamese to English (Easton, Reference Easton2010; Outila et al., Reference Outila, Piekkari and Mihailova2019). This translation was conducted by two independent researchers fluent in both languages. To ensure accuracy, a comparison was then made until the translation was finalized. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed.

Data Analysis

In line with the phenomenon-based research approach, we immersed ourselves in the data. We coded all transcripts and defined the patterns relative to the data. Four broad categories relating to the four pathways HCNs followed to entrepreneurship emerged relatively early in the analysis stage. Because we were somewhat surprised to have identified the four distinct pathways at such an early stage, we asked industry experts to check whether our initial labeling made sense. Once we were assured the emerging codes were meaningful, we labelled them MNC returnees, transitional hybrids, committed hybrids, and direct spin-offs. While collecting data from the 12 focal cases, we remained anchored in our research question: why and how do HCNs become entrepreneurs? We continued the coding process in accordance with the guidelines developed by Glaser and Strauss (Reference Glaser and Strauss1998) and Miles and Huberman (Reference Miles and Huberman1994). Our goal for each case was to explore independently emerging concepts characterizing the pathways and then analyze these with respect to the research question. Our primary purpose was to explore the contextual phenomenon in an original and genuine manner (Michailova, Reference Michailova2011); therefore, rather than drawing on existing theories or comparing the findings to literature in other emerging market settings, we remained open to new categories emerging inductively from the cases in this particular context. In line with recent critiques of narrow theorizing practices in qualitative methodologies (Plakoyiannaki et al., Reference Plakoyiannaki, Wei and Prashantham2019), we did not intend to build theories by conceptualizing constructs, capturing their causal relationships, or channeling our theoretical contribution in the direction of ‘factor analytic proposition or variance models’ (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2017: 368; Plakoyiannaki et al., Reference Plakoyiannaki, Wei and Prashantham2019). The coding exercise was useful for identifying emerging categories of pathways or themes relating closely to our research question. We also believe that reporting the phenomenon in the rarely studied context of Vietnam rendered the study both insightful and original.

RESULTS

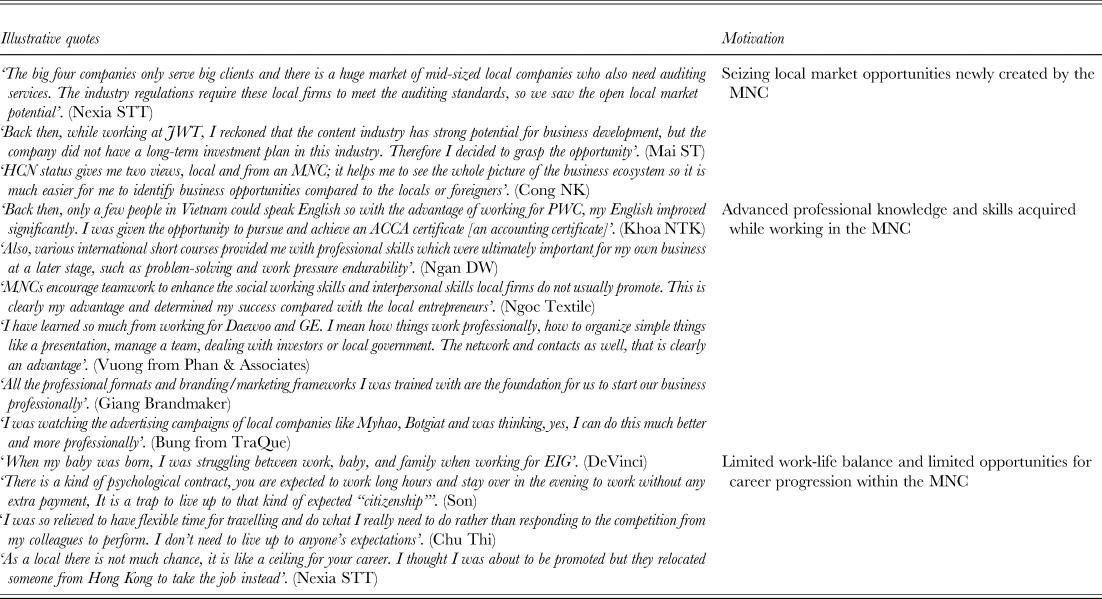

In this section we present the findings of our study. This first subsection addresses the first part of our research question: why do HCNs become entrepreneurs; while the second subsection is devoted to how do they achieve this. For clarity, we present our findings in summary form in Table 3 and then elaborate further upon them in subsequent sections.

Table 3. From HCNs to entrepreneurs: Key motivations

Why Do HCNs Become Entrepreneurs?

Because the focus of the research was on MNC employee spinoffs in Vietnam, our interviews began with questions exploring the key factors in Vietnam that facilitate this. Initially, the questions were rather open and the answers referred to numerous factors; however, through a process of data reduction and coding, these were condensed into the three main factors listed in Table 3: (1) seizing local market opportunities newly created by the MNC; (2) advanced professional knowledge and skills acquired while working in the MNC; and (3) limited work-life balance and opportunities for career progression within the MNC. We now elaborate on each of these factors.

Seizing newly created local market opportunities created by the MNC

Most of the businesses launched by MNCs in Vietnam were new to the local market when the economy opened up, especially in professional services such as auditing, shipping, insurance, and management and education consultancy. Numerous businesses within the country began shifting from industrial manufacturing and agricultural development toward services to embrace and pursue new business opportunities and address gaps that existed for decades. There was a growing demand for newly emerging high-knowledge intensive services at different scales. As one HCN from Nexia STT (DS1) commented: ‘The big four companies only serve big clients, and there is a huge market of mid-sized local companies who also need auditing services. The industry regulations require these local firms to meet the auditing standards, so we saw the market potential’. Expressing a similar view, another HCN from VinaCapital (PH1) reflected: ‘By working for an MNC, I could spot many investment opportunities’. Another HCN from Chu Thi (TH1) stated: ‘Back then, while working at JWT, I reckoned that the content industry had strong potential for business development, but the company did not have a long-term investment plan in this industry. Therefore I decided to grasp the opportunity’.

Notably, one interviewee who worked in a logistic service company (DS3) indicated that working in an MNC provides opportunities to see the potential of a market that is less likely to be recognized by local entrepreneurs: ‘HCN status gives me two views, local and from an MNC; it helps me to see the whole picture of the business ecosystem so it is much easier for me to identify business opportunities compared to the locals or foreigners’. This reflects HCNs’ ability to access much needed information. Given that the raison d’être of an entrepreneur is not ownership but negotiation and control (Casson, Reference Casson, Buckley and Casson1985), possessing unique information provides HCNs with more opportunities to be(come) entrepreneurs. Adopting the perspectives and position of being both an MNC employee and a local, HCNs are in the unique position of having a dual perspective through which to recognize unexplored market loops and establish their business.

Advanced professional knowledge and skills acquired while working for the MNC

Professional knowledge refers to the knowledge MNCs provide to employees through training courses or apprenticeship programs. Working in an MNC provides HCNs with excellent opportunities to acquire professional knowledge and skills not readily available elsewhere – giving them a distinct competitive advantage over local entrepreneurs. This is particularly the case in professional services where tacit knowledge and skills are less likely to be codified and transferred and thus remain largely embedded within HCNs. A shortage of such knowledge and skills in the local market creates a high demand for HCNs. This gives them confidence and strengthens their belief that they can effectively exploit their advantages if they run their own businesses.

Advanced professional knowledge (compared to that of local entrepreneurs) was the strongest reason identified across all cases when HCNs were asked about their motivation to leave the MNC and become entrepreneurs. For example, one HCN from Investive (DS1) shared his story as follows: ‘Back then, only a few people in Vietnam could speak English so with the advantage of working for PWC, my English improved significantly. I was given the opportunity to pursue and achieve an ACCA certificate [an accounting certificate]. Also, various international short courses provided me with professional skills which were ultimately important for my own business at a later stage, such as problem-solving and work pressure endurability’. An interviewee who worked for Ahlers (DS2) stated that most HCNs received a series of highly professional training programs that enabled them to work closely with various departments in the organization. Consequently, he acquired a wide variety of knowledge and skills that enabled him to adopt a holistic approach to business. As DS4 explained: ‘MNCs encourage teamwork to enhance the social working skills and interpersonal skills that local firms do not usually promote. This is clearly an advantage and determined my success compared with the local entrepreneurs’. Vuong from Phan & Associates revealed the following: ‘I have learned so much from working for Daewoo and GE, I mean how things work professionally, how to organize simple things like a presentation, managing a team, dealing with investors or local government. The network and contacts are also beneficial, that is clearly an advantage’. Brandmaker's founder commented: ‘All the professional formats and branding/marketing frameworks I was trained in provide the foundation for us to start our business professionally’. Bung from TraQue confirmed: ‘I was watching the advertising campaigns of local companies like Myhao and Botgiat and I was thinking, yes, I can do this much better and more professionally’. These and several other interview quotes clearly suggest there is knowledge spillover from MNCs to the local new businesses established by HCNs in terms of advanced service management, mentality, and ways of conducting business.

Limited work-life balance and few opportunities for career progression within the MNC

Our findings show that MNCs’ working environment, especially in Japan or South Korea, is typically stressful and demanding and often creates a hostile relationship between HCNs and their foreign managers. Across all cases, we identified a clear career pyramid with limited promotion opportunities for HCNs. There is also an additional implicit ‘expatriate favoring HR policy’ that gives expatriates an advantage over the locals (i.e., only expatriates can hold high positions in the company, which means there are no incentives for HCNs to make any further effort in their career development with the MNC). Moreover, compliance with international standards, the requirements for professionalism, and the deadline-focused nature of professional service firms all create a high-pressure atmosphere in which HCNs are expected to perform. Having no free time for themselves or their families impelled numerous employees to leave their jobs and start their own business. For instance, HCN from DeVinci (RE2) stated: ‘When my baby was born, I was struggling between work, baby, and family when working for EIG’. Furthermore, the pressure to perform created unhealthy competition among peers and colleagues. Such a highly competitive environment in MNCs presented severe challenges for HCNs and led them naturally to a decision to leave. For instance, one of the HCNs, Ms. Hong Anh at Chu Thi (DS2), decided to leave her job to start her own business and enjoyed her new-found autonomy and flexibility: ‘I was so relieved to have flexible time for travelling and do what I really need to do rather than responding to the competition from my colleagues to perform. I don't need to live up to anyone's expectations’.

How Do HCNs Transition to Entrepreneurs?

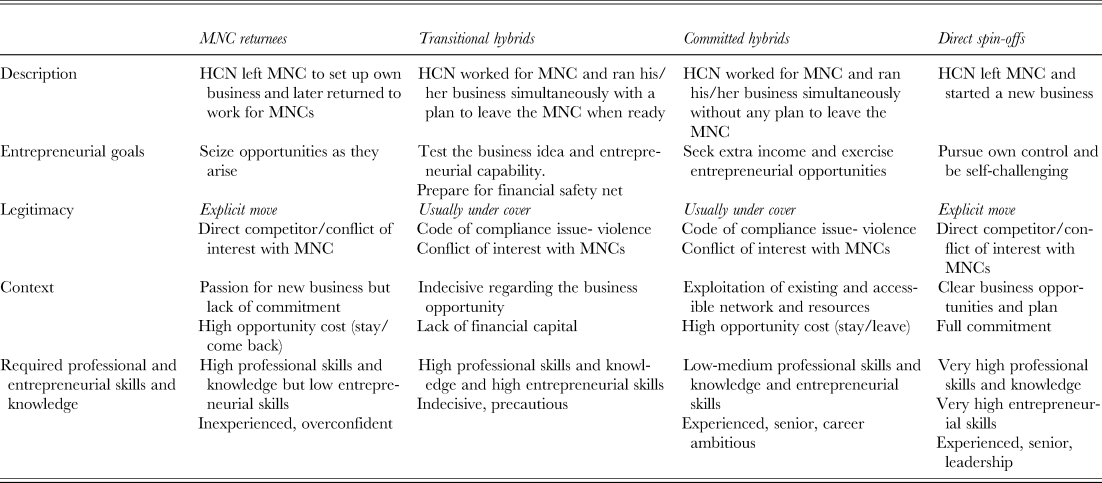

As depicted initially in Table 1 and elaborated on in Table 4, four different pathways leading HCNs to become business entrepreneurs emerged from our data, namely: (1) MNC returnees: those who launched their business but failed and returned to work for MNCs; (2) Direct spin-offs: those who quit their jobs and created new ventures; (3) Transitional hybrids: those who simultaneously established and ran their business while remaining employed for a while; and (4) Committed hybrids: those who simultaneously establish and run their business without any plan to quit their jobs. In the following sections, we analyze these pathways in greater depth.

Table 4. From HCNs to entrepreneurs: Migration paths and their characteristics

Path 1: MNC returnees

MNC returnees are HCNs who left the MNC that employed them to establish a business but then returned to work either for the same or a different MNC. They typically saw new available business opportunities emerging and were sufficiently confident to seize them. In our data, no clear pattern was observed regarding whether the new business was the same as that of the MNC; they ranged from a similar business sector to an unrelated business. These HCNs were confident in their professional knowledge and strongly believed they could manage the business on their own. However, our findings suggest that immature business plans caused by a lack of entrepreneurial skills and strong commitment discouraged them from continuing the business. Moreover, the stay versus leave trade-off between the benefits provided by the MNC and the difficulties of launching a business was the principal concern that led HCNs to abandon their new business. They were unable to bear the pressure of running a new venture and were not determined enough to abandon the (relatively) high income provided by MNC and take a risk with their new firm(s). Their entrepreneurial mindset was not strong enough. In the words of one HCN: ‘I found myself not passionate enough to take the risk, it is safer to be an employee so I sold my restaurant and came to KPMG’.

Tuan, who worked in the trade department of PS (RE3), was one among many MNC returnees in Vietnam. While working at a trade marketing division, he thought he could create a new venture and become the supplier of consultancy services for PS. However, having overestimated the vitality of the business opportunity, he could not persuade his former company to allow him to become their supplier. He also revealed that he did not possess the important business skills needed to run his own business. He explained: ‘Only when I left my company and started my new business did I realize that running my own business is more difficult than expected’. HCNs were often too confident in their ability to successfully launch a new business. They overestimated their professional knowledge while underestimating their entrepreneurial skills; skills their local counterparts may have acquired in abundance while working for local companies or running a business for several years. Their success at MNCs often led HCNs to believe in their ability to master environmental turbulence and market competition; sometimes, this belief was not justified. This was often a result of underrating some of the specificities arising from conducting a business alone. For instance, after spending five years running her own business, Vuong (Phan & Associates) (RE1) returned to work for the GE corporation and confessed: ‘Entrepreneurship is actually an extremely lonely job compared to an MNC job where we could request help from the company or from our boss anytime. It requires a huge responsibility, which means you have to do everything on your own. This life is actually horrible if one is not prepared for it’.

All interviewees concurred that the working conditions in an MNC were so different from those involved in establishing and running one's own business that often HCNs could simply not adapt to a new working life as an entrepreneur. Some respondents stated that they returned to the MNC because they did not want to lose the benefits they had enjoyed while working there: a high salary, a professional working environment with good support from a well-organized system, and a business class lifestyle. One interviewee from DeVinci (RE2) admitted that even though she recognized her entrepreneurial ability and passion, she still preferred the MNC life and eventually decided to return.

Path 2: Transitional hybrids

Transitional hybrids are ventures launched by HCNs who simultaneously work for an MNC and run their own business, albeit with a plan to leave. This group of HCNs do not plan to maintain their hybrid lifestyle in the long term. Their business is typically similar to that of the MNCs they work for; they, therefore, understand that a hybrid status may result in them breaking the code of conduct of the MNC. However, they are unsure whether they have a viable business idea and sufficient entrepreneurial skills to successfully run their business. This transition period would therefore help them nurture their business and ascertain whether they are, in fact, are up to the challenge of exiting and becoming full-time entrepreneurs. Fully cognizant of the contrasting conditions between the two working environments, they are not willing to countenance the difficulties associated with an entrepreneurial life. Interestingly, they also used this transition time to make use of the available access to MNC's resources for their private business. For instance, one HCN from GIBC (TH3) expressed a concern as follows: ‘The transition time gave me a chance to completely compare two different working conditions, to test my leave or stay decision and whether I was willing to leave a very high paid job for some uncertain path. It also helped to utilize the resources and network of my employer and determine whether my new service would be relevant for the target market’. This seems to be a strategic approach for HCNs to test market acceptance for their new business while challenging their entrepreneurial mindset, capabilities, and persistence.

Establishing transitional hybrid entrepreneurial firms has become a common phenomenon among Vietnam HCNs who are keen to develop a safety net for themselves. Due to high work pressure and competition at the MNC and limited options for career growth, numerous HCNs create their business while working at MNCs to provide a back-up option if their employment goes wrong or they cannot keep pace with MNC working conditions. These businesses are typically similar to that of the MNC and are therefore kept secret. For instance, MaiKT (TH1) disclosed: ‘When I left the job everyone was astonished to find I had my own business running alongside for the last 10 years. They felt sorry for me being made redundant at first’. Giang from Brandmaker (TH2) shared her view thus: ‘We have to prepare for our future, I would go nowhere if I stayed. High positions are usually planned for expatriates. Looking back, I think at least 20% of my former colleagues were building their own business alongside’. One of the conditions enabling these HCNs to set up their business alongside their MNC employment is the financial savings they accumulated as a result of the high salaries they received. Working for foreign companies gave HCNs an extremely good income (three to five times higher) compared with employees in local firms. This helped HCNs prepare financially for their new ventures once they felt the desire to run their own business. One informant from Brandmaker (TH2) stated: ‘Unlike a manufacturing business with lots of upfront capital commitment, the consultancy business requires much lower capital. I think I put down only about 100 mil VND (£3K) with my partners to start the business’.

Path 3: Committed hybrids

Committed hybrids are new ventures launched by HCNs simultaneously working for an MNC and running their own business without any plan to leave the MNC. They maintain and run their business as a side job while working for the MNC during the day. They remain in the MNC because their position provides them with the opportunity, networks, and even the market for their own business. One research participant from Vinacapital stated: ‘Working for the MNC gives me the opportunity to access promising projects, some of which I would invest in. With the knowledge and skills accumulated from my employer, I would be able to select good startup projects to invest in and become the co-founder of the business’. For these reasons, he decided to maintain a working life as both an employee and an entrepreneur. For instance, SG Thienly started his own business in a related sector. Staying in the MNC offered him the opportunity to approach and expand the market for his own business. There was no conflict of interest as his company's product was in the food sector and was not related to the business of the MNC. Nevertheless, he still could utilize his current network with the distributors, which was crucial for his own business. As well as the advantages of access to information and networks, several HCNs simply wanted to remain in MNCs. For instance, Chung (Samsung) stated that even though he was truly passionate about his own business, he did not want to leave the MNC because he had acquired new knowledge and skills through training.

We also observed that although the HCNs in this group were highly entrepreneurial-minded, they were also risk-averse; they did not want to lose their high and secure income from the MNC. Mr. Liem from Myquang que was able to satisfy his entrepreneurial desire by opening a restaurant chain that sold local noodles while maintaining a permanent position in the MNC. Although his own business was not related to his current job in the MNC, he wanted to run it because he had always dreamed of opening a business that would provide his customers with authentic and fresh food from the Central Region of Vietnam. However, he admitted that his MNC income was too high to risk leaving to open a business. Having made a similar decision, Khoa from SGThienly also refused to give up his high income from the MNC to concentrate solely on his business. The opportunity cost of leaving the MNC appeared to be too high for these HCNs.

As noted previously, these businesses usually operated under cover. HCNs utilized MNCs’ system to access market analysis, supporting systems, and knowledge to support their business. Thus, they did not publicly declare their names as entrepreneurs or co-founders. Some presented themselves as CEOs and/or founders under an alternative name to avoid breaching the labor law and MNCs’ codes of conduct. This was only possible due to the continuing weakness of Vietnam's institutional system.

Path 4: Direct spin-offs

Direct spin-offs are new ventures founded by HCNs after leaving their MNC jobs. This was usually an explicit move rather than one conducted under cover. These HCNs usually held senior positions in the MNCs, had a diverse experience, were financially relatively strong and self-sufficient, and were entrepreneurially prepared with a strong commitment to run their business. They were decisive in striving to pursue their autonomy in business and had clear business plans and ambitions.

Mr. Son from Ahlers (DS3) argued that only people who have a strong entrepreneurial mindset, staunch determination, and a powerful desire to pursue their business autonomy should follow this pathway. Both Son from Ahlers and Khoa from Nielsen (DS1) emphasized that they had longed to establish their own business since university. They both decided to leave their MNCs when they saw a great opportunity. Their business and leadership experience was acquired by holding a variety of job roles, including leadership positions, and through exposure to different working environments via the MNC rotation policy. These HCNs typically had a very clear business vision.

Additionally, some of our research participants admitted that having reached the highest position they could in the MNC; they lost motivation: there were no new substantive forms of knowledge or skills available for them to acquire if they continued to work in the MNCs. For instance, Ms Hong Anh at Chu Thi (DS2) stated: ‘After a long-time at the highest management position, you might find there is no space for you to learn new things, to try new things. You may want to leave to do something new’. She went on to elaborate: ‘Imagine, if I continue to work at JWT for 10 more years, my subordinates will have no opportunity to be in my position. Meanwhile, I want them to have the opportunity to learn, to be promoted. That is one of the reasons that made me to decide to leave the company even though I love my colleagues so much’. HCNs were self-confident and tended to leave their MNCs whenever an opportunity became available. They acted professionally and were determined to comply with the code of conduct of the MNC; they did not opt for the (typically illegitimate) hybrid model. Ms Hong Anh confirmed: ‘When I leave JWT, I never think of a day when I will come back. I want to put all of my determination into the new business’.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we explored the phenomenon of HCNs setting up entrepreneurial ventures in Vietnam's emerging market. The idiosyncratic nature of working for MNCs in emerging markets results in different motivations and pathways for entrepreneurial spin-offs compared with a conventional (Western) context. Our analysis identified four unique pathways followed by HCNs who become entrepreneurs in professional service firms: MNC returnees, transitional hybrids, committed hybrids, and direct spin-offs. Across these different pathways, a key factor that led to the survival of the newly established business was the ability of HCNs to manage the trade-offs between working for MNCs and launching new ventures. Our findings identified several such trade-offs: risk vs. regret management (the ability to decisively give up a high-income job and take the risk of running a business alone), stress vs. balanced lifestyle (work-life balance), no safety net at all versus having a solid safety net (being on one's own with low or no pay vs. being well paid by the MNCs) and, finally, making an explicit move vs. having an undercover status (legitimate vs. illegitimate status of new ventures).

HCNs decide which pathway would be the most suitable based on their perceptions of the risks they may take when starting their own business. Our findings show that the entrepreneurial spirit plays a crucial role in HCNs’ behavior. The more independent and entrepreneurial they are, the more determined they are to leave the MNC and commit strongly to their new ventures. Our findings also highlight two particular research issues that emerged alongside those presented in our analysis and which we discuss next.

MNCS as a New Gateway for Knowledge Spillover in Promoting Local Entrepreneurship via HCNs

As we have alerted to, the HCN literature focuses predominantly on MNCs and expatriates and how they can manage HCNs to utilize their key advantages. Some studies acknowledge the discrimination between expatriates and HCNs in terms of constraints on career opportunities as HCNs are typically further away from the (typically) powerful headquarters, not only in terms of physical distance but also in relation to nationality. This inevitably positions them at a lower level in the MNC organizational structure. Furthermore, HCNs often have less experience with and a more superficial knowledge of the MNC and a lower level of commitment and allegiance to the organization (Michailova et al., Reference Michailova, Mustaffa and Barner-Rasmussen2016). While consistent with some of these observations, our findings go further by examining HCNs’ new career choice as entrepreneurs. We offer a new perspective on HCNs as people acting as entrepreneurs rather than their well-established role in supporting MNCs’ localization strategy (Collings & Scullion, Reference Collings, Scullion, Scullion and Collings2006; Harzing, Reference Harzing2001b; Putti et al., Reference Putti, Singh and Stoever1993). They take opportunities created by MNCs themselves and assume responsibility for their own career development, which can even mean becoming direct competitors of MNCs. This is a provocative view that contrasts strongly with their stereotyped role as staff inferior to expatriates.

The HCNs in our study acted as international knowledge brokers, facilitating knowledge spillover from MNCs to the local market through entrepreneurial activities. Indeed, MNCs operating in emerging markets are often described as a key source of knowledge spillovers (Meyer & Sinani, Reference Meyer and Sinani2009). They provide a fertile training ground by offering advanced technology and occupational skills; they also develop market opportunities in growing consumer markets (Meyer & Tran, Reference Meyer and Tran2006) and serve as an avenue to access leading management practices. In fact, a raison d'etre for the existence of MNCs in emerging markets is that they have attractive capabilities and knowledge that compensate for the liability of foreignness associated with local institutions (Narula & Dunning, Reference Narula and Dunning2000). Our findings indicate that MNCs in emerging markets also become a gateway for their employees to commercialize intellectual assets within and beyond their current employment contracts. The professional knowledge, experience, skills, and networks HCNs acquire during their employment in MNCs are key drivers in them establishing new ventures and play an important role in the survival and success of HCNs’ new businesses. The HCNs in our sample obtained experience, knowledge, information, and skills from the MNCs where they worked. All our cases provide clear evidence of entrepreneurial experience at the time HCNs exit, an experience accumulated throughout their employment and including multiple job and leadership skills, market sensibility, and strategic thinking. The HCNs we studied also acquired other types of tacit knowledge, such as recognizing opportunities and market sensibility. They all acknowledged that the experience accumulated during their MNC employment afforded them clear advantages over other entrepreneurs in setting and running new local businesses. They considered this a key factor in the subsequent success of their businesses. Several of these have grown substantially and some are listed as being among the most successful upcoming startups in the country. Given the importance of MNCs as an employer of highly skilled labor in emerging economies, it is unsurprising that employee entrepreneurship outside the labor contracts of current MNC employees is a frequent avenue through which knowledge spillovers occur in emerging economies. HCNs seem to play a key role in this process.

Institutional Voids Promoting, Rather Than Suppressing, Unique Pathways for Entrepreneurship Among HCNs

Following the ‘Doi moi’ economic reforms, Vietnam quickly developed and emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies in South East Asia (King-Kauanui, Ngoc, & Ashley-Coutleur, Reference King-Kauanui, Ngoc and Ashley-Coutleur2006). In a relatively short period, the central government unleashed the local private sector's potential and attracted foreign investment (Quang, Reference Quang, Nankervis and Chatterjee2006). However, similar to developments in other transition economies, the centrally planned economy's formal constraints were weakened. At the same time, the formal institutions needed for a market economy, such as a well-defined property rights-based legal framework and an infrastructure to support market transactions, were under-developed (Boisot & Child, Reference Boisot and Child1996; Peng & Heath, Reference Peng and Heath1996). Until today, the road for development chosen by the Vietnamese government has remained that of a market economy under socialist guidance, encouraging the development of the private sector and attracting foreign direct investment.

Conducting business in Vietnam is often highly volatile due to frequent institutional changes, capital market swings, and macro-economic transitions. However, although such volatility imposes a business risk, it also provides entrepreneurial opportunities for those with the strategic flexibility to react to changing circumstances and seize new business opportunities. Such flexibility may be achieved through an alignment to institutional frameworks and the discovery and morphing of business opportunities that require specific ways of relating to business partners and authorities. ‘Institutional voids’ often inhibit the efficiency of markets and increase business risks: for this reason, firms may internalize markets for intermediate goods and services such as financial and human capital, and rely to a larger extent on personal relationships to organize exchanges (Khanna & Palepu, Reference Khanna and Palepu1997; Mair et al., Reference Mair, Martí and Ventresca2012; Meyer, Tran, & Nguyen, Reference Meyer, Tran and Nguyen2006; Pinkham & Peng, Reference Pinkham and Peng2017). Bruton et al. (Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Obloj2008) contended that emerging markets differ from developed markets in terms of the existence and stability of institutions that can provide new business opportunities. In emerging markets, entrepreneurs operate in unpredictable, volatile, and uncodified institutional environments (Meyer, Reference Meyer2001; Peng, Reference Peng2001; Webb, Bruton, Tihanyi, & Ireland, Reference Webb, Bruton, Tihanyi and Ireland2013). Institutional differences mean that emerging economies can be expected to influence different forms of entrepreneurship through which employees seek to appropriate returns on human capital investments (Becker, Reference Becker1964; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Khoury and Hitt2020). As documented in our analysis, one example of a specific context in emerging markets in which an entrepreneurial phenomenon unfolds is MNCs’ persuasiveness and importance as a host and driver of employee entrepreneurship.

Formal institutions with over-regulated enforcement in areas such as intellectual property rights might suppress the creativity and innovativeness of new businesses in the context of employee entrepreneurship in developed countries. Therefore, the established literature on employee entrepreneurship outlines only two types of pathways, spin-off and hybrid entrepreneurship. Our findings suggest that in Vietnam, different pathways exist in the transition from HCNs to entrepreneurs and this is mainly due to the idiosyncratic characteristics of institutions in emerging markets. They also indicate that weak institutional enforcement (in terms of company code compliance, copyright, and labor law) means support for entrepreneurship among HCNs comes in different forms – namely transitional hybrids and committed hybrids in competition with the existing businesses of MNCs. These hybrids usually operate under cover. Transitional hybrid path is a hedging option to develop a safety net for HCNs if they lose their jobs rather than a transitional path to test the markets as conventionally observed in the literature. Hybrid paths help them to maintain their highly paid income by MNCs which they do not want to comprise losing. Only weak enforcement conditions, in particular the lack of normative institutions, make possible prolonged periods of transitional hybrid entrepreneurship (McHenry & Welch, Reference McHenry and Welch2018). HCNs utilize their (former) MNCs to access market analysis, support systems, and knowledge to assist their businesses while at the same time bypassing the labor law and the codes of conduct of MNCs. This is only possible within a weak institutional context. Our study provides empirical evidence for the claim by Webb, Khoury, and Hitt (Reference Webb, Khoury and Hitt2020), that the absence of formal institutions results in different forms of entrepreneurship idiosyncratic to the context.

At the same time, we contend that the pathways we have identified and analyzed are not static: for instance, hybrid entrepreneurs may become MNC returnees or independent entrepreneurs. In the long term, as their own business develops and they cannot face the pressure from both their MNCs and their own business, they might decide to abandon their own business or sell it and become MNC returnee entrepreneurs. Alternatively, they might decide to become a direct spin off by leaving their MNCs and investing full-time in their venture. Moreover, issues relating to their family or their position in the MNCs may impel hybrid entrepreneurs to move onto another pathway. However, in this study we primarily focused on identifying observed alternative pathways and the possibility of moving between these. Future research can focus on the conditions and antecedents of such dynamic transitions.

CONCLUSION

Working for MNCs in less developed economies has long been considered an attractive job with higher pay, better conditions, and more and better career development opportunities compared to jobs provided by local firms. However, our empirical study indicates that numerous HCNs leave their MNCs with privileged working conditions and set up their own businesses despite entrepreneurial challenges. They follow different pathways when doing so. Adopting a phenomenon-based approach, through an inductive study of 12 service firms, we conducted an in-depth exploration of the key motivations and dimensions of these pathways in professional service firms in an emerging market context – Vietnam. Our study revealed three key motivations: the availability of unexplored market opportunities created by the businesses of MNCs themselves; the possession of advanced knowledge and skills; and the limited career progress that forces them to leave. We identified four distinct migration pathways: MNC returnees, direct spin-offs, transitional hybrids, and committed hybrids. In revealing these pathways, we contribute to the literature on both employee entrepreneurship and HCNs by providing insights into how knowledge spillovers occur through entrepreneurial migration by HCNs from MNCs to local entrepreneurship – a non-market transaction – in the context of an emerging market.

Our results also imply that MNCs play an important role in training and providing professional and entrepreneurial knowledge and business opportunities for HCNs starting entrepreneurial ventures. While this is often unintentional, knowledge spillovers may facilitate economic growth at a macro level. It may also lead to a brain drain inside MNCs where high-performing and talented HCNs with a high entrepreneurial orientation leave the company and start a new business. Our findings provide insights that will help make MNCs aware of the trade-off between benefits vs brain drain when dealing with HCNs. MNCs entering markets such as Vietnam may need to think carefully when hiring HCNs with high entrepreneurial mindsets, especially if they are not prepared to provide sufficient conditions to retain them and utilize their ability to provide innovation and strategic change MNC. In contrast to the conventional view, institutional voids may facilitate this entrepreneurial process rather than suppressing it. Vietnam is an exemplar for similar emerging markets; thus, our findings can be validated in future research in other markets. Vietnam is a new destination for multiple MNCs now shifting their business focus away from China due to the current trade war. However, successful penetration of this market requires MNCs to develop a local perspective and be fully aware of its dynamism. MNCs should think more about providing opportunities for their employees to become involved in starting a new business within their corporation or give them more power within their management scope. Understanding HCNs is an important step in that direction.