Introduction

Most people will experience the death of a loved one during their lifetime, and severe psychological suffering is often present during bereavement. In most cases, a grieving person does not require professional help, and the bereaved gradually recover to normal life on their own (Shear et al. Reference Shear, Ghesquiere and Glickman2013). However, during the past 2 decades, there has been increased recognition that grief may turn into a disorder, and several concepts and proposed diagnostic criteria sets have been used to understand such disturbed grief (Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Boelen and Xu2021; Shear et al. Reference Shear, Ghesquiere and Glickman2013; Stroebe et al. Reference Stroebe, Hansson and Schut2008).

In this study, we studied prolonged grief symptom severity. Such disturbed or prolonged grief has been described as disabling yearning that persists for a year or more after the loss of a loved one (Lundorff et al. Reference Lundorff, Holmgren and Zachariae2017). Other characteristic symptoms include disbelief and a lack of acceptance of the loss, emotional detachment from others since the loss, loneliness, identity disturbance, and a sense of meaninglessness. Over the years, different concepts have been used to describe “disturbed grief,” including “pathological grief” (Horowitz et al. Reference Horowitz, Bonanno and Holen1993), “complicated grief” (Shear et al. Reference Shear, Ghesquiere and Glickman2013; Stroebe et al. Reference Stroebe, Hansson and Schut2008) and “traumatic grief” (Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Bierhals and Kasl1997). Prigerson et al. (Reference Prigerson, Boelen and Xu2021) believe that the various scales they developed to measure pathological grief (referred to by them in the past as “complicated,” “traumatic,” and finally “prolonged” grief) actually measure the same phenomenon – prolonged grief disorder symptoms, and “prolonged grief disorder” was recently introduced to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 11 (ICD-11) and a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5TR) (Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Boelen and Xu2021; WHO 2022). Therefore, we will further use the concept “prolonged grief disorder” and refer to the symptoms included in such disorder as “prolonged grief symptom severity.”

Approximately 10% of bereaved individuals may develop prolonged grief disorder (Lundorff et al. Reference Lundorff, Holmgren and Zachariae2017). Previous research has identified risk factors for how close family members cope with loss, factors that are linked to different personal aspects of family members, for example, gender, age, attachment style (Maccallum and Bryant Reference Maccallum and Bryant2018; Mason et al. Reference Mason, Tofthagen and Buck2020), a lack of social support, low education, and the predeath level of depression and anxiety (Ghesquiere et al. Reference Ghesquiere, Martí Haidar and Shear2011; Stroebe et al. Reference Stroebe, Schut and Boerner2010). For example, Maccallum and Bryant found that attachment avoidance is predictive of greater depressive symptoms following the loss of a family member. Furthermore, attachment anxiety predicts greater levels of symptomatology in general, with higher levels of attachment anxiety being predictive of both prolonged grief and depression (Maccallum and Bryant Reference Maccallum and Bryant2018).

It is also known that family members’ sense of security during ongoing palliative home care (measured by a single overall question) can predict prolonged grief symptoms as well as psychological well-being and health-related quality of life 1 year after the patient’s death (Milberg et al. Reference Milberg, Liljeroos and Krevers2019).

A few studies have shown patient-related risk factors for prolonged grief symptom severity in family members of patients admitted to hospice, such as the patient’s age and perceived quality of care (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Haley and Small2013; Kramer et al. Reference Kramer, Kavanaugh and Trentham-Dietz2010; Mason et al. Reference Mason, Tofthagen and Buck2020). Younger patient age has been found to be a significant predictor for prolonged grief symptom severity in caregivers when caregivers have access to hospice bereavement services (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Haley and Small2013).

Furthermore, relational factors, such as the closeness of the relationship between family members and the patient and the family situation while the patient is alive, affect how close family members handle grief after the death of a loved one (Ghesquiere et al. Reference Ghesquiere, Martí Haidar and Shear2011; Kissane et al. Reference Kissane, Bloch and Dowe1996; Sekowski and Prigerson Reference Sekowski and Prigerson2022a).

Research has identified, in addition to risk factors for prolonged grief symptom severity related to the family member and to the deceased person, risk factors specifically present during bereavement both when patients were cared for in hospice and in palliative home care. Continuing bonds such as grief-specific coping strategies have been described. There is, however, still a lack of clarity as to which types of continuing bonds are related to (mal)adaptive bereavement outcomes. Both externalized continuing bonds (entailing, e.g., illusions and hallucinations of the deceased, representing attachment-seeking behavior, and denial of the reality of the loss and death) and internalized continuing bonds (entailing use of the deceased as an autonomy promoting secure base, representing the continuation of a trusting relationship and attachment figure) (Field and Filanosky Reference Field and Filanosky2010; Sekowski Reference Sekowski2021) have been positively associated with prolonged grief symptoms (Field and Filanosky Reference Field and Filanosky2010; Sekowski and Prigerson Reference Sekowski and Prigerson2022a, Reference Sekowski and Prigerson2022b; Stroebe et al. Reference Stroebe, Schut and Boerner2010) and with greater grief intensity (Field and Filanosky Reference Field and Filanosky2010; Ho et al. Reference Ho, Chan and Ma2013). However, Field and Filanosky (Reference Field and Filanosky2010) found that only internalized continuing bonds are related to posttraumatic growth (personal growth following a stressful event or trauma).

Thus, previous research has identified several risk factors for prolonged grief symptom severity in family members, but there is still a lack of knowledge regarding the multivariable effects between family members’ coping with loss and patient-related factors. Furthermore, there is a lack of knowledge regarding family members’ risk factors for prolonged grief symptom severity during bereavement, especially for family members of patients admitted to palliative home care. To our knowledge, most studies examine mixed populations with patients cared for through different kinds of care, and only a few studies have been published on the palliative home care context (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Haley and Small2013; Kramer et al. Reference Kramer, Kavanaugh and Trentham-Dietz2010). Being able to identify risk factors for prolonged grief symptom severity in family members during ongoing palliative care can help health-care staff find ways to support and intervene to reduce the risk of prolonged grief disorder after a patient’s death. The aim of this study was to identify risk factors for prolonged grief symptom severity 1 year after patient death in relation to (1) the family member and the patient during ongoing palliative care and (2) the family member during bereavement.

Methods

Study population and procedures

In this longitudinal study, the participants included family members of patients currently receiving palliative home care, and data (independent variables) were also collected from the patients during ongoing palliative care. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in Figure 1. Inclusion criteria for the family members included being a relative (a spouse, partner, child, or close friend) of a patient in palliative home care with a diagnosis of an incurable disease with an expected short period of survival and aged older than 18 years. The exclusion criterion was not being able to speak and understand Swedish well enough to complete the questionnaires. Details of the data collection method have previously been published and are briefly summarized here (Krevers and Milberg Reference Krevers and Milberg2015; Milberg et al. Reference Milberg, Friedrichsen and Jakobsson2014, Reference Milberg, Liljeroos and Krevers2019). The participants (family members as well as patients) were recruited from 3 specialized palliative home care units and 3 primary care–based palliative home care units in Sweden. Three of the units were advanced palliative home care teams (with a multiprofessional team that included 24-hour services and access to a backup ward) and 3 were primary care–based teams with a palliative care consultant and a specialist nurse available during the daytime. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for all the patients who were admitted to the participating palliative units were assessed by the staff of the palliative care team. All eligible participants received written study information and were asked by a staff member of the care team if they wanted to participate. No reimbursement was given for participation in the study.

Fig. 1. Flow diagram. aComparisons between interviewed family members (n = 237) and those who declined to participate (n = 41) revealed no statistically significant differences in terms of the family member’s gender, relationship to the patient, patient’s gender, patient having a malignant diagnosis (Chi-square; p > 0.05 in all of the 4 tests), or difference in the patients’ ages (mean 69.3 years [SD 13.7] vs. 71.5 years [SD 12.9]; p = 0.66; t-test). bCompared with patients who were interviewed, patients who declined participation were older (mean 75.5 years vs. 68.9 years; p < 0.01; t-test) but were similar in terms of gender and primary diagnoses (Chi-square; p > 0.05). cComparisons between the 144 family members interviewed during ongoing palliative care and the 99 who were also interviewed postloss revealed no statistically significant differences in terms of age (63.7 vs. 62.6; p > 0.78; t-test) and gender (male 46%, female 54% vs. male 47% and female 53%; Chi-square; p > 0.05).

The 5 interviewers were staff experienced in palliative care but not involved in the participants’ medical care. Most of the data were gathered in a structured interview, with the family member using verbally administered questionnaires. Some data, for example, the patients’ diagnoses, were collected via the palliative care team. Mindful of the family members’ difficult situations, we used short scales or single questions where possible.

The analyses conducted in this study were based on a sample of 99 family members who (i) in addition to the survey during ongoing palliative care of the patient, (ii) also completed a follow-up survey 1 year after the patient’s death, and (iii) the patient (i.e., the ill relative of the family member) who was interviewed during ongoing palliative care (see the overview of study enrollment in Figure 1). There were no cases where several family members of one patient were tested.

The demographic characteristics of the 99 family members and patients are displayed in Tables 1 and 2. There was no significant difference between family members who were interviewed preloss (N = 144) and postloss (N = 99) regarding age (63.7 vs. 62.6) and gender (male 46%, female 54% vs. male 47% and female 53%). The data were collected between September 2009 and October 2010 and have resulted in several previous papers (Krevers and Milberg Reference Krevers and Milberg2015; Milberg et al. Reference Milberg, Friedrichsen and Jakobsson2014, Reference Milberg, Liljeroos and Krevers2019, Reference Milberg, Liljeroos and Wåhlberg2020).

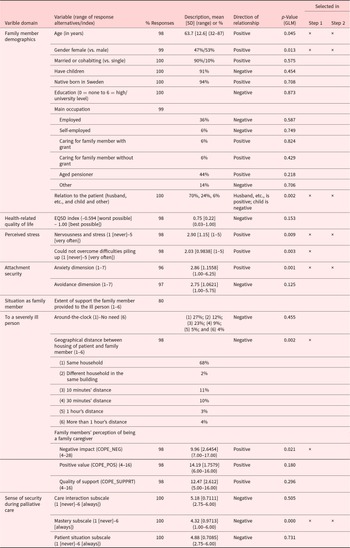

Table 1. Family member characteristics – preloss

Sample characteristics (n = 99) of the family member preloss data and analysis of the individual variables’ bivariate associations with the family members’ complicated grief symptoms 1 year after the patient’s death (dependent variable).

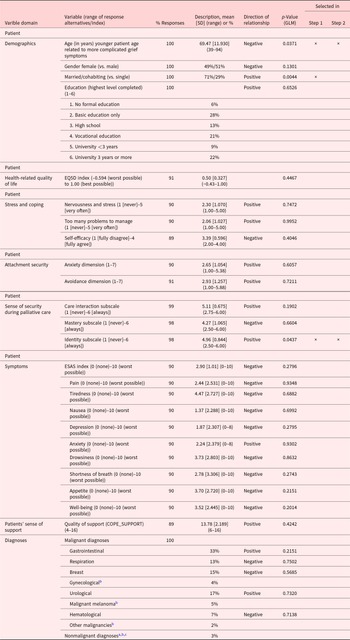

Table 2. Dyadic patients’ characteristics

Sample characteristics (n = 99) of the family members’ preloss data regarding their dyadic patients (n = 99) and analysis of the individual variables’ bivariate associations in relation to the family members’ prolonged grief symptom severity 1 year after the patient’s death (dependent variable).

a More than 1 alternative was possible.

b Too few (5% or less) to meaningfully compute.

c Neurological disease (n = 2) and heart or lung disease (n = 2).

Measures

Dependent variable

The family members’ prolonged grief symptom severity (dependent variable) during the past month was assessed with the Inventory of Complicated Grief Screening (ICGS) instrument using the mean value of the 9 items (5-point scale ranging from “never” to “always”) (Field and Filanosky Reference Field and Filanosky2010; Prigerson and Jacobs Reference Prigerson, Jacobs, Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe and Schut2001; Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski and Reynolds1995). Originally, the instrument consisted of 19 items (Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski and Reynolds1995), but it was further developed (Prigerson and Jacobs Reference Prigerson, Jacobs, Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe and Schut2001) and shortened (Field and Filanosky Reference Field and Filanosky2010; Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski and Reynolds1995). The 9 items covered the following: thinking of the deceased so much that it is difficult to do things one normally does, longing and yearning for the deceased, disbelief over the deceased’s death, a lost ability to care about other people or feeling distant from people one cares about, bitterness about the deceased’s death, loneliness since the deceased’s death, difficulty imagining life being fulfilling without the deceased, feeling as if part of oneself has died along with the deceased, and a lost sense of security or safety since the death of the deceased. To our knowledge, there is no ICGS cutoff value for prolonged grief symptom severity.

Independent variables

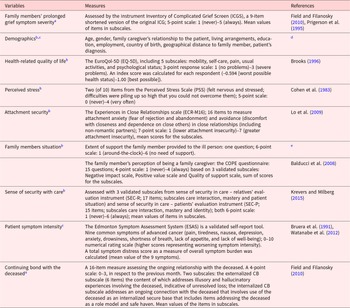

Variables potentially related to the dependent variable were evaluated using the following variables: demographics (the family member and patient); health-related quality of life, perceived stress, attachment security, the family member’s situation, sense of security with care (all 5 variables collected from family members during ongoing palliative care), patient symptom intensity (patient during ongoing palliative care), and a continuing bond with the deceased (family member 1 year after the patient’s death). All variables and measures used are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Overview of measured variables regarding patients’ characteristics and family caregivers’ characteristics pre- and postloss

a From family member 1 year after the patient’s death.

b Data collected from family members during ongoing palliative care.

c From patient during ongoing palliative care.

d Medical record.

e Developed by the authors.

Statistical analyses

Simple (step 1) and multiple (step 2) regressions were conducted as generalized linear models (GLMs, normal distribution, and identity link) using Statistica 13 software. In step 1, numerous simple GLMs were conducted to select independent variables that explained variation in the dependent variable. All variables that scored p < 0.1 were brought forward to step 2. A generous selection criterion (p < 0.1) was preferred over a traditional criterion (p < 0.05) to reduce the risk of discarding potentially useful variables. In step 2, all the selected variables were used, and this involved a model selection approach identifying the best model among all possible models (i.e., all possible combinations of the independent variables selected from step 1 and computed in step 2). The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to compare models. The AIC estimates the amount of unexplained variation while applying penalties for increasing model complexity. Hence, in the second step, we subjected the 15 independent variables to the model selection approach.

An assessment of missing data did not indicate any systematic patterns, and the number of missing values was small (Tables 1 and 2). Where there were missing values, specific analysis was performed with information excluded for the respondent in question, although the respondent could be included in other analyses.

Ethical considerations

The regional board of ethics in Linköping, Sweden, approved the study (Reg. no. 144–06). The participants were assured of confidentiality and the right to cease participation at any time without giving any reason. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

The patients’ and family members’ pre- and postloss characteristics are displayed in Tables 1, 2, and 4. The mean value (SD) of the 9 questions regarding prolonged grief symptom severity 1 year after patients’ deaths was 2.26 (0.65), and the median value was 2.81.

Table 4. Family member characteristics – postloss

Data collected in interviews of family members (n = 99) one year after the patient’s death and analysis of the individual variables’ bivariate associations with the family members’ prolonged grief symptom severity 1 year after the patient’s death (dependent variable)

Step 1: simple regression

The purpose of step 1 was to select candidate variables for step 2. Hence, the overall results of numerous analyses are only presented in Tables 1, 2, and 4, with their selection status indicated.

Preloss characteristics

Nine of the family member’s preloss characteristics, including the family member’s age, gender, relation to the patient, perceived stress level (nervousness and stress and inability to overcome compounding difficulties), attachment security (the anxiety dimension), geographic distance to the patient’s housing, perception of being a family caregiver and sense of security during palliative care (Mastery subscale) (Table 1), and 3 of the patient preloss characteristics, including the patient’s age, married/cohabiting status (vs. single), and sense of security during palliative care (Identity subscale) (Table 2), were selected (p < 0.1; for the model selection approach (step 2).

Postloss characteristics

Three of the family member’s postloss characteristics including continuing bond – internalized, continuing bond – externalized, and the EQ5D index (Table 4) were selected (p < 0.1; to the model selection approach (step 2)).

Step 2: model selection analysis

The model selection chose 10 independent variables from the 15 included in the analyses (Table 5).

Table 5. Best model selected in the model selection analysis (step 2) involving 15 independent variables and how the selected variables contributed toward explaining the variation in family members’ prolonged grief symptom severity 1 year after the patient’s death (dependent variable) (N = 91)

a Nonstandardized estimate.

Of the 10 variables included in the final model, 8 involved the family members’ responses (6 variables collected during ongoing palliative care and 2 collected during bereavement), while only 2 involved the patients’ responses (Table 5).

The following variables were positively related to family members’ prolonged grief symptom severity (increasing p values): a family member’s older age; continuing internalized bond; female gender; marital status as husband, wife, or partner to the patient; continuing externalized bond; and feelings of nervousness and stress during ongoing palliative care and the patient’s sense of security during palliative care (identity subscale and family members’ attachment security: anxiety dimension).

The following variables were negatively related to family members’ prolonged grief symptom severity: family members being a child to the patient; older age in patients; and family members’ sense of security during palliative care: mastery subscale.

Discussion

In this study, conducted in a palliative home care context, we identified several variables associated with family members’ prolonged grief symptoms 1 year after the patient’s death, and the final generalized linear model generated consists of 10 variables associated with prolonged grief symptom severity.

In summary, the final model shows that how family members coped with prolonged grief symptoms was reflected not only in variables linked to the family members themselves but also in aspects linked to the patients and the relationships between close relatives and patients. The model also shows a link between preloss variables (in both patients and family members) and postloss variables (prolonged grief symptoms in family members). These findings support the importance of family-level perspectives within palliative care, which has also been stressed by others (Field and Filanosky Reference Field and Filanosky2010; Mehta et al. Reference Mehta, Cohen and Chan2009; Stroebe and Boerner Reference Stroebe and Boerner2015).

According to the final model, older age in family members, younger age in patients, and family members being female were associated with a higher risk for prolonged grief symptom severity, and these findings are supported by previous research (Lundorff et al. Reference Lundorff, Holmgren and Zachariae2017; Mason et al. Reference Mason, Tofthagen and Buck2020; Sekowski and Prigerson Reference Sekowski and Prigerson2022b), although our result contradicts findings reported by others unable to find an association between gender and prolonged grief symptoms (Ghesquiere et al. Reference Ghesquiere, Martí Haidar and Shear2011; Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Neergaard and Jensen2017). In addition, family members’ relationships with the patient were also included in the model, and such an association has been shown previously (Ghesquiere et al. Reference Ghesquiere, Martí Haidar and Shear2011). The results of the present study also highlight a relationship between family members’ perceived nervousness and stress during ongoing palliative care and prolonged grief symptom severity 1 year after the patient’s death. To our knowledge, perceived stress and prolonged grief symptoms have not been studied with a longitudinal design before, although an association between perceived stress and prolonged grief in elderly parents losing their only child has been shown previously (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Ren and Wang2022).

Continuing bond – internalized and continuing bond – externalized variables were included in the final model, both with a positive association with prolonged grief symptoms. Our findings are in line with some reports (Field and Filanosky Reference Field and Filanosky2010; Ho et al. Reference Ho, Chan and Ma2013; Sekowski and Prigerson Reference Sekowski and Prigerson2022a; Stroebe et al. Reference Stroebe, Schut and Boerner2010) but contradict other results showing positive associations between internalized continuing bonds and adaptive bereavement outcomes (Field and Filanosky Reference Field and Filanosky2010). Sekowski recently suggested an alternative approach to continuing bond dimensions, to understand this inconsistency in previous results and clarify good or poor adjustment to loss in relation to continuing bond dimensions (Sekowski Reference Sekowski2021). In that study, continuing bonds were examined in bereaved persons from Poland (n = 244; death of a family member). This resulted in a new 2-factor structure that was theoretically hypothesized (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Fonagy and Bateman2008; Fonagy and Target Reference Fonagy and Target1996) and statistically developed and that includes (i) concrete continuing bonds, defined as more concrete, direct, and less separate relation with the deceased and (ii) symbolic continuing bonds defined as more symbolic, indirect, and separate relations with the deceased. Further analysis showed that concrete continuing bonds were a negative predictor of adaptation to grief and symbolic continuing bonds were a positive predictor. These results can deepen our understanding of why most research to date, as well as the results of the present study, indicates that both internalized and externalized continuing bonds are associated with maladaptive grief, in contrast to the theory-based hypothesis, which states that internalized continuing bonds should facilitate adjustment to grief (Field and Filanosky Reference Field and Filanosky2010; Ho et al. Reference Ho, Chan and Ma2013; Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski and Reynolds1995; Sekowski Reference Sekowski2021). While every externalized continuing bond item was concrete, not every internalized continuing bond item was symbolic, which may contribute to difficulties with adjustment to grief. Instead, 3 of the items measuring continuing bonds were discarded due to substantial loadings on both factors (Sekowski Reference Sekowski2021). Although Sekowski did not study the 16-item continuous bond scale from 2010 that we used in this study, but instead the 11-item scale from 2003 (Field et al. Reference Field, Gal-Oz and Bonanno2003), one can hypothesize that there may be similar problems with one/several internalized continuing bond items also measuring concrete continuing bond aspects.

One of the selected variables in the final model of the present study is the family members’ sense of security mastery subscale. The mastery subscale measures aspects such as feeling confident enough to handle the situation as a relative and having been adequately informed about what to expect in the relative’s care in terms of treatments or health progress. Others have suggested that when relatives’ needs during palliative care are not met due to inadequate treatment and care, they may feel less secure, which could put them at a greater risk of experiencing anxiety (Mehta et al. Reference Mehta, Cohen and Chan2009). Our findings indicate that such a sense of insecurity due to lack of mastery may also contribute to a higher risk of postloss prolonged grief symptom severity in family members.

The model building also selected patient identity as a subscale of the patient’s sense of security with care. We are surprised about this showing a positive association. That is, higher patient scores on this subscale during ongoing palliative care were associated with higher family member scores of prolonged grief symptom severity 1 year after the patient’s death. The patient identity subscale consists of 4 questions on the patients’ experiences of receiving health care in their preferred location, of their home feeling secure (given their health condition), of them being able to be themselves when interacting with health-care personnel, and of them being able to do what is most important to them in their daily lives. Consequently, the results indicate an association between one or several of these measured aspects in the subscale and the dependent variable (i.e., family members’ prolonged grief symptom severity). At the time of the interview, approximately 90% of the participating patients received palliative care at home, and 70% of the 99 participating family members were husbands/wives/partners who shared the home where the patient received care. Considering this, a possible hypothesis/explanation for our result could be related to the place of palliative care being the home shared by the patient and the family member. Although a patient may have felt that they received (palliative) care in the preferred location (i.e., at home) and that the home felt secure to him or her, the home as a place of care may have contributed negatively to his or her family member’s experiences and later, in some way, contributed to the family member’s prolonged grief symptom severity after the patient’s death.

Although severely ill patients often prefer to die at home (Fereidouni et al. Reference Fereidouni, Rassouli and Salesi2021) and often feel secure during palliative home care (Milberg et al. Reference Milberg, Friedrichsen and Jakobsson2014), previous research has also shown that home as a place of care at the end of life can contribute to the burden on family members (Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Hayes and Bryant2019; Higginson et al. Reference Higginson, Sarmento and Calanzani2013; Sathiananthan et al. Reference Sathiananthan, Crawford and Eliott2021). The findings of our study may indicate such a potential conflict between patients’ and family members’ needs when palliative care is received in a shared home that needs to be addressed. This is supported by a study by Sathiananthan et al. (Reference Sathiananthan, Crawford and Eliott2021) who reported that family members make “promises” to the patient to be cared for at home during the end of life, that they feel implicit expectations to do so, that they struggle to meet the demands of such caregiving to keep “the promise” made to the patient, and that they often abstain from expressing worries about the place of care to avoid burdening the patient and/or damaging their relationship with him or her. It seems important that palliative practitioners support and actively initiate conversations between the patient and family members concerning the place of care and encourage family members to express their opinions regarding the patient’s preferences regarding home death.

Furthermore, family members’ attachment anxiety was associated with more severe prolonged grief symptom severity in the present study and was also selected in the final model. Attachment anxiety relates to a person’s appraisals of the availability and responsiveness of attachment figures in times of stress. These results are in line with previous findings (Sekowski and Prigerson Reference Sekowski and Prigerson2022b) showing a positive correlation between prolonged grief disorder symptom severity and both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. Individuals high in attachment anxiety are overly dependent on interpersonal relationships to provide them with a sense of security and worry that resources will not be available in times of need (Weber Falk et al. Reference Weber Falk, Eklund and Kreicbergs2021). Additionally, attachment anxiety is more likely to interfere with effective and sensitive caregiving and has also been found to significantly predict prolonged grief symptom severity in previous research (Maccallum and Bryant Reference Maccallum and Bryant2018). Therefore, it is important to identify family members with attachment anxiety early in preloss care to reduce the risk of postloss prolonged grief symptom severity. Family members high in attachment anxiety should receive psychological support to reduce the risk of developing prolonged grief symptom severity.

Methodological considerations

Some aspects of the methods used are worth pointing out. As mentioned in the introduction, several concepts and proposed diagnostic criteria sets are used to understand disturbed grief (Boelen and Lenferink Reference Boelen and Lenferink2020). The concepts resemble each other, and some have evolved from a previously presented concept of disturbed grief, contributing to confusion (Boelen and Lenferink Reference Boelen and Lenferink2020). Recently, an ICD-11 code and a DSM-5TR code have been assigned to “prolonged grief disorder” (Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Boelen and Xu2021; WHO 2022). Prolonged grief disorder can be diagnosed using a 13-item scale (PG-13 R) (Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Boelen and Xu2021), and this instrument includes a subset of the items included in the Inventory of Complicated Grief – Revised (Prigerson and Jacobs Reference Prigerson, Jacobs, Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe and Schut2001), which is a revision of the Inventory of Complicated Grief (Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski and Reynolds1995). In this study, family members’ prolonged grief symptom severity was assessed using the instrument inventory of complicated grief screen (ICGS), which is, as with Prolonged Grief -13 (PG-13 R), a subset of the Inventory of Complicated Grief – Revised (Field and Filanosky Reference Field and Filanosky2010; Prigerson and Jacobs Reference Prigerson, Jacobs, Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe and Schut2001; Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski and Reynolds1995). Hence, although the instrument used in this study (ICGS) to measure prolonged grief symptoms is somewhat outdated, it is related to the recently developed instrument (PG-13 R) designed to diagnose prolonged grief disorder.

The participation rates of the 3 parts of data collection were relatively high: 76% of eligible family members during ongoing palliative care were interviewed (231/302); 65% of eligible patients were interviewed (174/267); and 69% of eligible family members, where both the patient and his or her family member had been interviewed during ongoing palliative care, were interviewed 1 year into bereavement (99/144). The study population of 99 did not significantly differ from the 144 family members who were interviewed during ongoing palliative care regarding age or gender. This suggests that the findings are generalizable to family members of patients who died under palliative home care models similar to the studied Swedish models. However, compared to patients who were interviewed, patients who declined participation were older (mean of 75.5 years vs. 68.9 years). The reader should also be aware of the relatively small size of the study sample and that some existing relationships between variables may not have been significant due to insufficient statistical power (Type II error).

The purpose of the study was exploratory, and therefore p values should be treated with some caution due to multiple testing increasing the risk of type I error (rejecting a true null hypothesis).

Although some of the data regarding the family members were collected at 2 different time points (during the patient’s palliative home care period and 1 year into bereavement; longitudinal design), the associations between prolonged grief symptom severity postloss (dependent variable) and continuing bond postloss (independent variables) might not be causal. Longitudinal research into the trajectory of these phenomena would be a valuable addition to improve our understanding further.

In conclusion, in this study, 10 variables associated with prolonged grief symptom severity were selected in the final generalized linear model. The findings indicate that family members and patients should be seen as a unit in palliative home care in programs aiming to prevent/decrease prolonged grief symptom severity in family members after the patient’s death.

Further research is needed regarding controlled interventions offered to family members with risk factors for prolonged grief symptom severity, as identified in this and other studies, with the aim of supporting adaptive coping with bereavement, facilitating family members’ sense of security and mastery during the palliative phase, and deepening understanding about the role of continuing bonds.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.