The Mithraic lid: Iconographic interpretationFootnote 1

The lid is very fragmentary, but the sequence of the organization and of the representation can be easily reconstructed (Figure 1). It is a flat lid with a frontal panel of white imported marble, probably from Thasos (cf. Appendix B for the petrographic discussion). The panel is organized in three main sections, including the figurative scenes of the relief in the lateral sections (A and C in Figure 1) and a metrical inscription in tabula ansata for the central section (B in Figures 1 and 2 in particular), determining a frontal emphasis and also a converging schema for the two lateral reliefs.

Figure 1. The lid: general view of all the fragments with their position (photo: Chieti University archive).

Figure 2. The inscription in tabula ansata and the two Nikai holding the ansae of the tabula (photo: Chieti University archive).

The central section of the panel (section B in Figures 1 and 2 for details) is characterized by four fragments which constitute the complete tabula ansata. The inscription is not perfectly centred on the epigraphic field, especially for the first line, but is regularly organized on four lines (for the transcription and analysis see below in this contribution and in the Appendix A by S. Struffolino).

The tabula ansata is framed by mouldings, a concave and a rounded regular one, totally surrounded by a flat band, framing and enclosing the tabula. The two lateral ansae present similar moldings and listels, determining a homogeneous framing of this central section.

Two winged Nikai are carved on both sides of the tabula and are represented in profile as they move towards the centre and while holding the ansae with both hands. Their head and gaze is turned elsewhere, backwards, becoming in this way the link between the side sections and the central section and smoothing the way from the figurative scenes to the inscription. Both Nikai are wearing a long, thick and richly draped chiton, which is presented in a specular iconography, similar for the two figures, but slightly differing for the right one, which is represented with the left leg more visible through the dress or for a slit of the robe. The dressing, in both figures, is enriched by a short and draped apoptygma, covering the chest and bust, and ending at the hips; it leaves the arms naked and it is girded with a belt or strip, which is thicker in the right figure, while for the left one it seems to be thinner and less visible under the draped folds. The gesture of walking towards the tabula determines, then, in both figures an antithetic iconographic composition, with an unstable ponderatio, based on a bent leg moving forwards, while the second is placed straight and backwards, with the centre of gravity placed between the two legs, in order to give the impression of a movement in progress. Also the faces of the two figures are similar but not identical, but not for a specific or physiognomic characterization of each Nike, rather for an intent of differentiation, and maintaining an idealization in their representation. Both the hairdressings were made using a very thin chisel, to outline the hair strands, and a drill for carving more deeply the curls and to create a more chiaroscuro effect. The figure on the right is represented with the hair probably gathered at the nape of the neck, not falling on the shoulders, and the head is covered by a hat, the so-called Phrygian cap. The Nike on the left, moreover, presents a softer-looking hairstyle, with locks that touch the shoulders, without any cap, while two raised curls determine a richer hair style with a ‘top-knot’ arranged in a bow, which is quite popular and widely attested at Cyrene in the representation of Artemis and Aphrodite, as well as Apollo (Huskinson Reference Huskinson1975, nn.56,57,58, pl.23, 29–30; Paribeni Reference Paribeni1959, nn.153, 163). The wings of the two Nikai are just slightly visible, both due to their fragmentation and their being partly covered. Close to the right leg of the left figure a small dog is represented, but certainly linked with the backward scene, with Mithras.

The use of the tabula, for the inscription in lids of sarcophagi with frontal panels, seems to be widely attested between the second and the fourth centuries AD (for close parallels see the epigraphic appendix below), as also the tabula ansata, often presenting similar winged figures holding the tabula. The flat band framing the panel and the tabula seems to be quite frequent both in sarcophagi and lids dating between the second and the third centuries AD. For the mouldings of the tabula, the metrical composition and the typology of lid, parallels can be found in the panel with relief of the lid with seasonal Geniuses dating to between the middle and the third quarter of the third century AD (for the online database https://www.collezione-m.it/descrizione-opera-archeologia_27_ita.html -03/01(2021), as well as in the Petronius Melior lid at the Louvre (Baratte and Metzger Reference Baratte and Metzger1985, n. 2) and with other examples in the Vatican (Kranz Reference Kranz1984, n. 90; Ferrua Reference Ferrua1987, inv. PRI 0679-A, 3–20; Fasola Reference Fasola1961, inv.PRI 0679, 237–267; Bielefeld Reference Bielefeld1997, Vaticane inv. PRI 0564-D) and at Villa Pamphilj (Calza et al. Reference Calza, Bonanno, Messineo, Palma and Pensabene1977, n. 260).

The lateral ala C of the lid's figurative panel (C in Figure 1 and see Figure 3 for a more detailed view) is quite fragmentary and lacks large sections, therefore the reconstruction is based on 7 fragments (A01 – 1 c-d, A01 – 2, A01 – 3, A01 – 4) but with large gaps. It consists of a large figurative series of scenes, with numerous figures and all of them are wearing particular clothes, with anaxyrides, soft walking boots and a Phrygian cap, which confirm the ‘Mithraic interpretation’ (for the typology of dressing related to Mithras and the Mithraic representations, see in particular García Sánchez Reference García Sánchez2012, 124–134; but also Clauss Reference Clauss1990, Reference Clauss2000; Cumont Reference Cumont1903; Vermaseren Reference Vermaseren1963; and also contributions in EJMS online).

Figure 3. Particular of the section/ala B of the panel.

The fragments A01-1c and 1d are directly linked with the central section of the panel (just mentioned above); the fragments A01-2 are related to the lower part of the lateral section and guarantee the perfect match of the different sections. They are characterized by the evident representation of hooves of a bull. The scene is very fragmentary, but everything seems to be included within a specific ‘architectural space’, which appears to be outlined by vertical elements, in the form of small pilasters with decorative elements, quite simple and consisting of a thin wavy line and deeper incised dots. Two pillars (but just one is still preserved) were probably framing the entrance of a cave, which is formed in a slightly lower relief. In this way the pilaster represents a sort of monumentalisation of the cave or naiskos evoking the cave, possibly within a Mithraeum. The frame of the cave presents thin vegetal elements, according to a precise iconography evoking the ritual consecration by Zoroaster of a cave rich in flowers/vegetal elements and water sources for Mithras (Porph. de antro nymph. 6,4 – mentioning Eubulos author of a History of Mithras – Hier., in Iovinian. 2,14) and can be found in numerous Mithraic representations, as for instance in the reliefs from Interamna (CIMRM 670, fig. 191) and Rome (CIMRM 415, fig. 114). The specific use of a differentiated level of relief for the pilaster may be a method by the sculptor for creating an optical effect in a foreshortened view, and to mark with monumental architectonical elements the entrance of the cave/niche cave. Also the relief of the hooves of the bull are represented in a different thickness, indicating that the animal is moving, coming out from the cave or entering backwards recalcitrant and pushed by ‘someone’ who is preserved just in the lower part. The figure, in fact, is represented just outside the entrance of the cave, as moving towards the entrance, facing the animal. The figure is also wearing a Phrygian cap and a short mantle, which appears raised in the fragment A01 – 04. The scene seems to represent Mithras in the moment just after the capture of the bull, which is represented generally in very different ways. For instance in the relief from Dieburg (CIMRM 1247, fig. 323) the bull is already inside the cave and seated in the middle of the pilasters outlining the entrance. The figure can be therefore identified as Mithras, who, during the taurophoria (that is the transportation of the bull into the cave) is represented just after the capture, but before the sacrifice. The representation of the bull being pushed into the cave by Mithras is then a narrative expedient of the storyboard of the exploits/labours of Mithras, including the hunting of the animal, its transport and installation in the cave and then the sacrifice. Moreover, the human figure in this scene (as is clear from the hat in fragment A01-4 and the shoes in fragment A01-1) is also represented larger than the other figures; it is, therefore, the main figure on the complete scene of the right section of the panel. The taurophoria is not often represented among the acta of Mithras; obviously the tauroctonia (bull-slaying scene) is the most represented and key moment. However, it has here a symbolic value, it directly evokes the ritual passages of the Mithraism: the transitus of the god and of the bull evoke the passages and stages of the initiations (Beard et al. Reference Beard, North and Price1998, 289; Neri Reference Neri2000, 227–245, in particular 242–243), relating in this way to the other figurative section of the panel (A in Figure 1). Mithras, therefore, is represented in this scene ‘transporting’ the bull during the transitus, as a moschophoros; the iconographies related to this specific moment of the Mithraic events are various, such as keeping the bull on his shoulders, as for instance in the relief from Sidon (CIMRM 77, Figure 28) or carrying or pushing the bull, as in our case, and as attested in other representations (for instance at Vindobala, description in CIMRM 839; but also, nn.77, 729, but in particular n.48.8). Moreover, the specific iconography of this scene, the transportation of the bull, seems to suggest, more closely than other variations, what Statius is writing (Theb. 1, 719 sg.): Persei sub rupibus antri / indignata sequi torquentem cornua Mitram.

Two figures follow the scene, in fragments A01-03a (Figure 3), which are not completely preserved, but the Phrygian caps are complete, and part of the legs and feet. Although in poor condition, the iconography, as well as the ponderatio of the two figures (with the legs crossed), seems to allude to the representation of the two dadophoroi (torchbearers) of Mithras: Cautes and Cautopates, who are often represented in Mithraic reliefs and paintings (Hinnells Reference Hinnells1975; numerous representations of the two torchbearers can also be found in CIMRM, Cumont Reference Cumont1956). The fragments A01-3b and c (Fig. 3), attest, again in a very fragmentary way, a male veiled figure who is moving towards Cautes and Cautopates, and is carrying a leafy twig (possibly of an olive tree or oak), brandishing it towards the two dadophoroi. The figure could be interpreted as a cult initiate represented during a specific moment of the ritual ceremonies.Footnote 2 The last fragment of this section, (A01-3d in Fig. 3), is quite difficult to interpret: it is another figure wearing a Phrygian cap (which is the only part still visible) and is carrying a torch and extends his hand to the head of the veiled person. Obviously the presence of the torch can be interpreted in different ways, as a symbolic allusion, again, to one of the dadophoroi, or as the attribute of a priest during a specific ceremonial step, or a metaphorical allusion to the second grade of the Mithraic initiation. According to Sophronius Euusebius Hieronymus, writing in the fourth century AD, it was the grade of Nymphus, also named bridegroom or chrysalis; it was under the protection of Venus, and the elements which were used generally as ‘metaphorical symbols’ and iconographic attributes are a torch/lamp or the diadem of Venus (Hieron., Epist. 107 ad Laetam).

The scenes which are represented in this fragmentary right side of the panel of the lid have a homogeneous direction, iconographic trend and rhythm, which increases gradually to arrive at the representation of the transitus of the bull in the cave, where the presence of Mithras probably represented the acme of the gradual ritual path. Despite the fragmentary nature of the pieces, the scenes here seem to present a strong correlation of events, mainly throughout specific Mithraic rituals in front of the cave. The presence of a figure which is velato capite (veiled head), may suggest that what is represented here is the ceremonial initiation, or grade of initiation, of an adept to the cult. Moreover, the choice to represent the cave, which was the hearth of the cult, as a sort of ‘monumentalized’ cave or rock-cut niche with external pilasters or jambs with decorations, suggest an iconographic allusion to the cave-niche of a Mythraeum, in a parallel symbolic representation of the original cave as well as of the niche-cave of a specific Mythraeum, where possibly the adept was taking part in the rituals. The typologies of decorations which were usually painted or curved in relief along the borders of the cultural cave-niches of the Mythrea, were quite different: from the representations of the complete series of the Zodiac, to scenes of the birth and of the youth of the god, or to simpler decorations.

The scenes, therefore, are not just generic representations of Mithras and Mithraism, but it seems that the sculptor was representing specific ceremonies related to the dead person, within a specific Mithraeum, which was characterized by architectonic elements, alluding to a naiskos effect for decorating the cave-niche, and by a statue of Mithras taurophoros with its own iconography.

The lateral ala A of the panel of the lid includes the fragments A01-5, A01-6, A01-7 and A01-8 (Fig. 4), again in a very fragmentary state of preservation, but with scenes more complete than the other part and therefore easier to interpret from an iconographic point of view.

Figure 4. The scenes of the ala A of the vertical panel of the lid.

The fragment A01-5 (in Fig. 4) is directly connected with one of the Nikai, attesting the continuity with the central fragments. It is probably the most important scene, with Mithras represented seated, slightly larger in size, with a pileus and a draped dress with short sleeves and while keeping the head of the bull, just after the tauroctonia (the sacrifice of the bull, which is the main event of the rituals and of the acta of Mithras: Beck Reference Beck, Luther and Beck2004; Clauss Reference Clauss1990, Reference Clauss2000; Cumont Reference Cumont1903; Näsström Reference Näsström and Frizell2004; Vermaseren Reference Vermaseren1963). The left arm is folded and is represented in the act of supporting Mithras’ head while the elbow of the god is resting on the animal's head, which is preserved just for a small part. The right arm is, again, folded, but the hand is on the muzzle of the animal. It is not the typical representation of the tauroctonia in progress, which presents generally a Mithras in the acme of the ritual activities while killing the bull with a knife in one hand (generally the right one) and keeping the animal's head still by holding it by the horns, with the other hand. In this case the ritual sacrifice is already done and Mithras is assuming a resting position, just after the culmination of the ceremonial events. It's a quite rare representation, although it might not be considered an ‘iconographic hapax’ (as done just once); for instance, in a statue from Rome (Clauss Reference Clauss1990, p. 88, fig. 44) Mithras is resting in a similar way, after the sacrifice, seated on the bull, with the typical iconographic schema with one leg folded and the second leg located straight behind. Both in the statue from Rome and from the first scene of the ala A of the panel from Ain Hofra, the god presents the head and the gaze turned away from the bull, without any complacency for the death of the animal, as the standard iconography of the tauroctonia was imposing. Moreover, in our lid, he withdraws from the victim and faces backwards, towards a figure which is represented smaller and veiled. The particularity of a figure velato capite must have had ritual meaning, probably alluding to the initiate (which is obviously the dead person); the attitude of this small figure is particular, because he holds the index of his right hand in front of his mouth, in the typical iconography intimating silence. The enigmatic gesture certainly evokes specific rituals of the Mithraic mysteries. In particular, the Libellus Magicus of Paris, a text mentioning Mithras among other gods, is specifically recommending to the initiates to place the finger of their right hand on the mouth and to repeat for three times the invocation ‘silent, silent, silent!’ in front of the god.Footnote 3 Between the god and the initiate a strange spike-shaped element is visible, rich in incisions in the form of an ear of wheat: it is certainly the tip of the bull's tail, which is often represented in its metamorphosis in Mithraic reliefs (CIMRM, nn.172, 173, 208, 321, 335, 350, 369; Turcan Reference Turcan1980, 345 Abb. 3; Merkelbach Reference Merkelbach1984, 319 Abb. 70). In fact, the legend attests that after the sacrifice of the animal, the tail of the animal was transformed into an ear of wheat, as a symbolic element for emphasizing the Mithraic mysteries as rituals perpetrating the fertility and richness of the nature. The strange dysmorphic rendering of the tail/wheat ear is not an imprecision of the sculptor, but an expedient to emphasize the process of metamorphosis from tail to wheat ear still in progress and alluding in this way to both elements. From the representation of Mithras, soon after the bull-slaying scene, the representation is completed by the small dog looking backwards, which is represented just below the fragmentary scene. Generally, during or just after the tauroctonia, the dog is represented below the bull, while licking the blood from the bull's wound, as attested in numerous reliefs (a wide range of examples can be found in CIMRM). The dog is usually represented as rampant on two legs, but there are also parallels with the dog presented on his four legs, as in our relief of the lid (CIMRM, n.339, 397). The parallels with the numerous other examples of reliefs related to the bull-slaying scene, which presents a fairly standardized presence of elements, make it possible to hypothesise that in the missing section, together with the bull, there was also a scorpion and a snake. Generally the scorpion is represented as squeezing the bull's testicles to collect its sperm and the snake crawls under the bull, both with strong chthonic meanings and alluding to the fertility of the earth which can be perpetuated thanks to the Mithraic rituals.

This main scene is probably followed by the fragments A01-6 a, b, c, d and e (see Fig. 4), which join together quite well, giving us the opportunity to better understand the meaning of these new two scenes. The first scene is the representation, with numerous details, of flowing water, probably alluding to a river, which has been constructed using in combination a thin chisel for the waves and a drill curving deeply for chiaroscuro effects for the movement of the jets of water. The water moving in a copious and convulsive way downwards seems to allude to a sculptural transposition of a waterfall. This iconography is echoed in one of the acta of Mithras, relating to the ‘miracle of the water’, in which, according to the legendary events, water from a rock came downwards, copiously, and after that the god hit the rock with one of his arrows (Clauss Reference Clauss1990, 44, fig. 4). Moreover, because of the ‘miracle of the water’, one of the epithets of Mithras is specifically: fons perennis (CIMRM V 1533). Moreover, the presence of the water is also contemporaneously used as cesura, for interrupting the main scene with Mithras resting on the bull, and the following scenes. The link between the fragments A01-5 and A01-6 works, even though they are chipped, also from the iconographical point of view. In this section, which preserves more fragments it is also possible to see the different tool marks attesting different kinds of carving: the drill is used in long, running channels, especially for the hair and for outlining the weaves of the ‘miracle of waters’, and for punctual elements, such as the pupils of the eyes; at least two different kinds of chisel are widely attested: a thinner one and a second slightly thicker with deeper incisions. The way to use the running drill is particular, in patterned channels in the hair and in the waters, to emphasize the chiaroscuro of the relief and the movements of the hair and flowing waters.

Just after the ‘waterfall’ a male figure, almost complete, is seated, but with his back to what has been seen until now, and looking towards the following scenes, probably in continuity with them. The figure is represented as seated on a rectangular item, which is decorated by thin circular incised elements: it could be interpreted as a throne or a sella, which is represented in foreshortening with a forced perspective, which has been used by the sculptor to show both the side and the frontal view of the chair. A thin and softly rounded pillow is represented, with fringed endings. The throne or sella then presents a curved backrest. The male figure is wearing both the anaxyrides and the tunica, but not in a short version as is typical of the dressing of Mithras and Mithraic personages, but longer, up to the knees, according to an iconographic schema which is generally used in the representation of the Pater – the highest grade of initiation of the Mithraic mysteries (the seventh), which is under the tutelage of Saturn. The god is often represented in close relationship with the birth of Mithras from a rock (Iust., Tryph. 70; Commodian. istruct. 1,13 -invictus de petra natus; Firm. Mat. err. prof. rel. 20,1.) and in this occasion is generally presented as sleeping, veiled and resting on a pillow, as in the statue in the Mithraeum of S. Prisca in Rome (CIMRM 478) and in some painted representations (CIMRM n.44 and 48). Moreover, the presence of a softly draped roll from the right shoulder may attest the representation of a himation, completing the outfit. The left arm and hand, which are roughly sculpted, show again a forced perspective, and are holding a longish stick with a curved end. The head is preserved just for a small portion and shows curly hair and a plain thick hat.

The following fragment A01-7 (Fig. 4), then presents several figures, with well-known iconographic schemata, so easier to interpret, although here they assume a symbolic meaning with stratified allusions. Starting from the right, is a standing female figure, without the head, because this part is lost, with a naked bust and shoulders, while a rich and draped himation is represented round the hips and was probably also covering part of the back and the head. From the head the draped mantle was probably covering the left shoulder and arm, while the right shoulder and arm were left naked. The element in the left hand is quite unusual: it is a strange stick, while the right arm is folded upwards and the hand is holding a pomus/apple. The ponderatio of the figure is based on the right leg, while the left one is slightly folded and backwards. The iconographic features and schema as well as the apple were used as attributes and allow an easy interpretation of the figure as Venus. The iconography is certainly derived from well-known prototypes of Aphrodites, which influenced the Roman statues of Venus: starting from the Phidian Aphrodite Urania, which is much more austere, but with the same rhythm in the ponderatio; then there is the strong influence of the Praxitelean Aphrodite, with its tones and sinuous rhythms, often transmitted to Roman copies and re-elaborations as mediated by the numerous statues of Aphrodite dating to the Hellenistic period that became common prototypes for the statues of Venus in Roman times. Although the ‘aulic parallels’ are suggestive and striking in relation to the Urania, Cnydian or the Aphrodite of Melos or the Venus of Capua, there are recurrent iconographic echoes in the representation of Aphrodite-Venus with a widespread standardization in the main schema but vivacious and original elements in the details. It is also important to remember the numerous variations of this type of Aphrodite which have been found in Cyrene and in Cyrenaica (Paribeni Reference Paribeni1959, nn.241–302, in part. 243) attesting a wide use of this iconography and types influencing the schema of the Venus in this relief. The representation of Venus in a Mithraic relief is certainly conceivable and coherent with the rest of the scenes, in fact, Venus is the planet and the goddess representing and tutoring the second grade of initiation, that is the stage of Nymphu. The following figure, strictly in association with Venus, is Eros, represented as an infant, in profile, while moving towards the goddess and with his left hand in the act of touching Venus’ mantle. Eros is winged and naked, presenting soft and rich curly hair, with a thin string, wrapping the head. Again, the iconography of Eros and Erotes is in general quite popular. Both in the case of Eros/Erotes and Venus the iconographic schemata were generally popular and widespread, used everywhere throughout the empire and often with lively local reinterpretations but always moving from common bases. In this scene, although the association Eros and Venus may have a ‘conventional’ explanation within classical mythology, in a Mithraic context the compresence of the two personages can emphasize the passage among grades of the initiation. In particular, Venus/Nymphus is here represented symbolically with Eros which is also associated to the fourth grade of initiation, and assumes in the Mithraic rituals of initiation the function of mystagogos (helping and supporting the passages). For instance in a relief from Capua the Eros mystagogos is guiding the Nymphus, which is represented in the form of Psyche, through his passage (CIMRM, n.186).

The following male standing figure, although not completely preserved, is certainly, for attributes and iconography, Mars. He rests upon his left leg, wearing a draped mantle, and with his left hand is holding a spear and a circular shield. Obviously, if one of the levels of reading the scene can be interpreted as the usual familiar association Mars/Venus/Eros, a deeper and symbolic level of interpretation, again on Mithraic bases, sees Mars as the planet and the god, which protects the third grade of initiation of the Mithraism: the degree of the Miles.

What follows just after, in the fragment A01-8 a and b (Fig. 4), is quite fragmentary and difficult to interpret. Only two heads are visible and probably a third figure, which is completely lost. The first head is represented in profile and wears a petasos and it could be interpreted as Mercurius, associated with the first grade of Mithraic initiation: the step of the Corax. The hat is certainly quite particular and with a frontal visor which is not usual in normal helmets, but typical of the petasos. Moreover, just at the back of the head the upper part of a caduceus seems to be represented (in particular one of the snaky upper elements). This second element, although quite fragmentary, seems to confirm the interpretation of the figure as Mercurius; however, the poor preservation of the relief makes it difficult to define a specific iconography for this god.

After this head two identical heads are represented, the first one completely preserved, while the second has just the silhouette of the upper part of the head visible, in a sort of ‘iconographic duplication’ of the previous figure. The two heads are represented in profile, leftwards, facing the previous figure and characterized by young faces, softly rich hair, with a sort of diadem or curly tuft on the head in form of stars or flames or feathers (For the Dioscuri with the star on the head Schraudolph 1993). The hairdressing of the Dioscuri finds parallels with one of the Dioscuri (the left one) in the lid with Dioscuri from the Vatican (PRI 0679 in Ferrua Reference Ferrua1987 and in Fasola Reference Fasola1961). They seem clearly identifiable with the famous twins Castor and Pollux, the Dioscuri, sons of Zeus/Jupiter, which were transformed by their father in a couple of identical stars in the constellation of the Δἰδυμοι or Gemini, in the Latin version (Cat. 10). Therefore, the particular flamed tufts or diadems on their heads could be a direct allusion to the stars; often the two twins are represented associated with stars, as in the silver coin issues of republican denarii where on the pileus or on their heads the stars are represented. In Mithraic contexts, as for instance in the explicative mosaic of Felicissimus at Ostia, the use of the pileus ending with a star is attested, as a symbolic and iconographic metaphor for them; in this mosaic the two hats with stars have been interpreted as the Dioscuri, as symbolically associated also with Cautes-Lucifer and Cautopates-Hesperus. In the scene of the relief from Ain Hofra, the Dioscuri may also represent instar Iovis, as a metaphoric and iconographic allusion to Juppiter, who is the god and the planet related to the fourth grade of initiation, that is Leo.

Moreover, other three fragments must be mentioned here, because of their possible relationship with the Mithraic lid. During excavations of Tomb C, which is located just to the east of Tomb A (Fig. 5), in a quite superficial stratigraphic locus, three fragments of a frontal panel of a lid with very close relieves have been found. Apparently they belonged to a second tomb, but without any connection with the sculptures and the sarcophagi of the context. Moreover, the locus of provenance was related to a later frequentation above a stratigraphic layer relating to the collapse of Tomb C. Looking carefully at the fragments, it seems plausible, for marble, typology of lid, iconographic elements, thickness and tool marks, that they might belong to the Mithraic lid of Tomb A. Their location, quite far from the original context in a second tomb and in a secondary context, may be explained by the removal of the fragments from Tomb A during early lootings of the tomb, already in antiquity (see Appendix C by E. Di Valerio on the context of the finds). On the basis of the stratigraphic data, the looting events happened probably soon after an earthquake, which determined the collapse of the structures, while both tombs and part of the sculptures were still partially visible and therefore already robbed.

Figure 5. Ain Hofra, Cyrene: the plan of the tombs A and C (by A.Santarelli, E.Di Valerio and A. Buttarini).

The fragments are presented here in order to complete the general view of the lid, to remind us of the different provenances and to emphasize that if there was looting in these tombs, moving the fragments of this lid all around the area, we need to complete the excavations of the entire area between the two tombs and in front of Tomb C, before concluding definitively on the iconographic reconstruction of the lid and its restoration.

The first fragment (Fig. 6) is characterized by a relief which has been realized using both a thin chisel and a drill carving deeply and more sporadically; with a stronger chiaroscuro effect. The single fragment is difficult to interpret, but compared with the other fragments of the Mithraic lid, and specifically with the scene of the ‘miracle of the water’ (see the graphic reconstruction in Fig. 7), it became clear that it probably belonged to the lower part of the waterfall from the rock.

Figure 6. The fragment with a relief simulating the water (photo Archive of Chieti University).

Figure 7. Photographic reconstruction of the possible original location of the fragment (Archive of Chieti University).

The combination of this fragment with the rest of the lid seems to work for the representation of the rock and then to the passage from the rock to the throne of Saturnus/Pater. Moreover, in the lower part of the fragment, just below the last waves, there is a sinuous snake tail, which was probably represented as moving towards Mithra and the bull (in the fragment A01-05, in the Fig. 4). The presence of the snake, together with the dog and the scorpion, as mentioned above, is widely attested in representations of the tauroctonia.

A second fragment, which has been found not far from the first one, in room B of Tomb C and in the same stratigraphy (SU/locus 303) presents an interesting scene (Fig. 8) with two standing figures, in a gesture of quite intime familiarity. A first figure (B in Fig. 8) is standing, with a naked bust, but with the himation draped around the hips and the legs.

Figure 8. The fragment with the two embraced figures (photo Archive of Chieti University).

The legs are crossed with the right leg folded and positioned over the left one, which is straight. The figure is embracing the second person (A in Fig. 8) with the left arm, while the right arm is not visible because it is probably located on the shoulder or on the back of the male figure named as A (in Fig. 8). The position of the second figure (A) is quite particular in its rhythm and ponderatio, with the two legs crossed similarly, that is with the left leg folded and located over the right one. Because of the fragmentary preservation it is impossible to understand the position of both arms of this second figure. The dressing is similar in both figures in the rendering of the roll of the himation around the hips, but while figure B has a naked bust, figure A is completely dressed with draped long, possibly soft trousers, probably the so-called ‘oriental anaxirides’ (García Sánchez Reference García Sánchez2012) mentioned by Latin sources as ‘persian sarabara’, and described by Isidorus as ‘fluxa ac sinuosa vestimenta’ (Etymologiae, 19, XXIII). The iconographic schema of the two embracing figures finds close parallels with contemporaneous lids representing Eros and Psyche in the same iconographic schema, for the gestures of the hands in the embracement and for the position of the crossed feet, as well as for the attitude and the ponderatio of the two figures, which derives from an Hellenistic prototype (McCann Reference McCann1978, figs 149 and 150, 116–117).

The third fragment (Fig. 9) has been found associated with the other two and is made of the same marble. It consists of a fragmentary mask, which is typical of lid panel endings of this type. Generally these heads or masks finished the two lateral sides of the frontal panel, and were always facing in opposite views. They were used as lateral markers, and closed on both sides the figurative scenes of the panel. Only the lower part of the face is preserved, with a profile view. The mouth is half open, with a fleshy and rounded lower lip. The incision between the lips is regularly cut and quite deep. The chin is marked and rigid, while the left cheek is softly rendered. Just a small section of the nose is preserved, suggesting a rounded left nostril which is marked by a lateral wrinkle. Only a small part of hair is preserved, and it seems to be arranged long and soft behind the neck.

Figure 9. Fragment with the mask which finished side A of the lid (photo Archive of Chieti University).

These types of masks or heads on lids with frontal panels is widely attested between the second and the third centuries AD. A good parallel can be found in a similar lid (which is described as ‘sarcofago ad alzata’ with lateral masks) in the Triumph of Dionysus Sarcophagus at Palazzo dei Conservatori at Rome (McCann Reference McCann1978, fig. 142).

The inscription

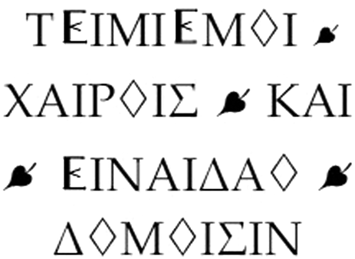

Looking now at the inscription:

Τ{ɛ}ίμιέ μοι χαίροις καὶ ɛἰν Ἀΐδαο δόμοισιν

Timios, my dear, might you be happy even in Hades’ houses!

The hexametric inscription (which has been recently included in the GVCyr051 - https://igcyr.unibo.it/gvcyr051) mentions, as a start, in vocative form, the name of the dead person, Timios, which is not a commonly found name. It is attested in Cyprus relating to a Timios, who married Alexandra, daughter of Herodes Magnus, according to Titus Flavius Iosephus (Antiquit. Iud. 18, 131, 4; see Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews1987, 440; infra, Append. A). Although rare, it is probably the name of the dead person.Footnote 4

The transcription of Τ{ɛ}ίμιɛ is included within the cases of transcription ɛι instead of long iota and is related to the iotacism.Footnote 5 The text of the epigram takes its origin from a literary repertoire of epic tradition. The poetic reference is Homer, Iliad 23, 19 e 179: χαῖρέ μοι, ὦ Πάτροκλɛ, καὶ ɛἰν Ἀΐδαο δόμοισι.

It is the last farewell of Achille to the dead Patroclus. The farewell form is echoed also in the Alcestis (435) of Euripides and is re-used in epigraphic contexts, as in an example from Smyrna.Footnote 6 The second hemistichion (καὶ ɛἰν Ἀΐδαο δόμοισι) is a Homeric formula, that usually goes from the trochaic caesura to the end of the line and is attested also outside the farewell form.Footnote 7

The first hemistichion of the inscription (Τ{ɛ}ίμιέ μοι χαίροις) with the name of the dead person is obviously re-adapted on the basis of the needs of the meter and funerary context, changing the name and the grammatical mood but preserving the message of farewell, which goes up to the penthemimeral caesura. The tabula ansata, which contains the inscription, evokes the triumphal signs. The vegetal elements (hederae distinguentes), which adorn the inscription but also functionally used for framing the words, are typical of the second and third centuries AD (Guarducci Reference Guarducci1967, 395 ff.). The only hedera distinguens, which has been deliberately located in the middle of the line, between χαίροις and καὶ, at the end of the first hemistichion, is the same as the penthemimeral caesura.

In the inscription of Timios, the καὶ before a vowel is long, contrary to what happens with the Homeric verse and with the Epic tradition, which in similar cases presents the feature of the shortening in hiatus. This phenomenon finds parallels in some late hexameters.Footnote 8 The inscription of Timios seems to reveal the use of the Homeric phraseology in the tabula which is ‘pre-worked’ in the workshop. The first part of the verse was then adapted to the name of the dead person. Moreover, a Homeric expression became a serial funerary formula. The juxtaposition of the two cola determines the peculiarity of the καὶ long in hiatus. Even the lay-out of the text, which isolates the καὶ at the end of the line and follow it by the hedera distinguens, probably emphasizes this phenomenon.Footnote 9

It is difficult to establish if there is a link between the inscription and the Mithraic scenes of the lid. The citation certainly has poetic meanings; the presence of a serial formula including a traditional element of the Homeric religion, such as Hades, seems to attest to the conventional use of the verse, which may belong to a different moment of the finishing of the carving of the lid. However, in order to give a more complete view, let us look at a parallel of the first part of the inscription (Τ{ɛ}ίμιέ μοι χαίροις) and the expression attested by Firmicus Maternus (de err. prof. rel. 19,1): νυμφίε, χαῖρɛ νέον φῶς … , which was used for the initiate to the grade of Nymphus. Moreover, there is a possible connection, albeit not so strong, between Mithraism and Hades.Footnote 10

If these elements can be seen as reliable, the verse mentioning Hades may have been for the initiates an allusion to one of the grades of initiation, the stage of Nymphus, which is also emphasized in the Mithraic scenes of the panel, as mentioned above. If so, there could be a combination/coincidence of iconographic, ritual and verbal meanings, which are finalized to a symbolic and allusive representation of the curriculum of Timios as initiate of Mithras. However, apart from this hypothesis it is impossible to present further interpretations.

Conclusive interpretations and religious issues

In conclusion, the dating of the lid, on the basis of the iconography, the use of the tabula ansata and the types of hedera distinguens in the inscription (see also the Appendix A, by S.Struffolino), as well as the forms of the use of Mithraic symbols, seem to suggest a possible dating between the end of the second and the first half of the third century AD.

The two lateral alae of the frontal panel of the lid are difficult to explain, while numerous elements refer to a Mithraic context. The scenes seems to be organized in two different thematic groups: a first group including the acta of Mithras, with images relating to the taurophoria, the location of the bull within the cave-niche, the evocation of the tauroctonia, and the miracle of the water; a second group of scenes directly attesting the degree of initiations, with the representation of the symbolic elements/figures attesting the grades of the initiation to the Mithraic cult.

Moreover, the representation of the flowing water, which directly symbolizes the miracle of the water, is also, at the same time, alluding to the constant presence of flowing water during the ritual meals, and also used as cesura between two different groups of scenes.

This continuous use of symbolic stratified meanings in the scenes of the lid, reflects a typical Mithraic iconographic and ritual language, with theological, mythological, literary and ritual levels strictly related and interconnected, but just for an audience of initiates. The close relationship among different sections is frequently used, as for instance in the use of the dog to represent the moment just after the tauroctonia which is also functional it its symbolic meaning of the dog as related to the forth degree of the Mithraic initiation, that is the level of Leo, under the control of Jupiter, which reminds us of the metaphoric scene with the Dioscuri.

Concerning the three new fragments which have been found in the near by tomb (known as Tomb C), the Mithraic subject seems to be quite clear from the dresses of the two standing figures; however, it is quite difficult to hypothesize the joining of this fragment with a specific section of the lid. The position of the legs could match with the position of the feet of the two male heads of the section C (Fig. 1), in the fragments A01-04 and A01-02 (Fig. 3), but dress of the half-naked figure seems more typical of a female figure, more like the dress and attitude of a Venus. This specific feature, however, could be, again, part of a symbolic language of the Mithraic context, using a male figure in female dress or a Venus, as a marker of the grade of the Nymphus, which is under the protection of Venus.

The initiate into this stage was also known as Chrysalis and was represented in female dress, with the iconographic schema typical of Psyche, as in the relief from Capua, where the male figure is dressed as Psyche with female dress, with an himation in a similar arrangement. Moreover, if in our case it is Psyche/Chrysalis which is represented here, the strange element just slightly carved at the back of figure B could be the lower part of the wings. Moreover, the Nymphus (Chrysalis/Psyche) had also the specific epithet of ‘bridegroom of Mithras’ and the embrace between the two figures could symbolically represent the embrace between Mithras and the initiate during the reception of the priest of Mithras to the initiate into this grade. It may suggest a sort of transposition priest/Mithras embracing Psyche/initiate, throughout a pluri-stratified symbolic iconographic language.

Certainly this fragment belongs to the Mithraic lid, but at the moment it is quite difficult without other pieces to find the perfect combination with the rest of the fragments of the lid. It could have been located within the scene mentioned above, but it could also belong to the initial part of section C of the lid which was not found during the excavation of tombs A and C and, in this case, it was part of a further scene.

So all the grades are attested in the scenes of the panels, often relating to each other, and used in combination for specific meanings.

The first grade: Corax, under the protection of Mercurius is represented in the fragment A01-08 (Fig. 4), where, although fragmentary, the petasos and the upper part of the caduceus are an evident allusion to this god and grade. The second grade seems to be widely attested. It is the grade of Nymphus and it is represented through the iconography of Venus in the fragment A01-07 (Fig. 4) and also emphasized by other ‘allusions’ to this grade and status. The third grade, that is the Miles, is then represented through the iconography of Mars (fragment A01-07 in Fig. 4), which is represented standing and holding a spear and a shield. The fourth grade, which is the Leo, is evoked by the representation of the Dioscuri (fragment A01-08 in the Fig. 4), sons of Jupiter, as well as by the dog as initiate and a final reference in ala A of the panel. The fifth grade, that is Perses/Luna, is attested by the presence of Cautopates, the torchbearer in ala C (one of the two heads with a Phrygian cap in Fig. 3), because he is protecting and representing this stage and status. The sixth grade, that his Heliodromos/Helios, similarly to the previous stage, is represented by one of the torchbearers in ala C, that is Cautes, but at the same time a reference to this stage is also represented by the small Eros in ala A (Fig. 4, fragment A01-07): moreover, among the acta of Mithras, the representation of the taurobolium (fragment A01-05, ala A, in the Fig. 4), is another allusion to the sixth grade. The seventh grade is the status of the Pater, which is associated with Saturn (as a god and a planet); this god is then recalled in the first scene (just after Mithras and the ‘miracle of the waters’) in ala A (fragment A01-06 in the Fig. 4), as seated on a throne.

Together with the different stages of the Mithraic initiation, the role of the initiate/dead person is emphasized, through the representation of the dead person as initiate to the Mithraism, in the two veiled figures on both figurative alae of the panel, where the velato capite (veiled head of the two figures) assumes the direct meaning alluding to the ceremonial role of the dead person.

The presence of an Eros mystagogos, in ala A (Fig. 4, fragment A01-07)), together with the Nymphus / Venus, probably focuses mainly on this step of the various grades, as does the inscription, in a symbolic strategy of communication, using in combination iconographic schemata and literary texts, concentrating on the degree of Nymphus, probably with the aim of representing and communicating symbolically the ritual cursus honorum/curriculum of the dead person.

Timios, therefore, could have been a cult adept, who died at a young age and his premature death did not allow him to finish his transition to further grades of the Mithraic initiation. Also the use of the Homeric verse, that is the last farewell of Achille for his young companion Patroclus, is clearly alluding to the youth of Timios; as does the sarcophagus, with the representation of Phaedra and Hippolytus (see the find n.3 in the Appendix C by E. Di Valerio), and specifically the death of Hippolytus during his youth seems to allude to the premature death of Timios. The iconography of the death of Hippolitus, in the sarcophagus, is an iconographic schema which is also known for the premature death, in a similar way, of Phaeton. Moreover, the subject who has been represented on the same sarcophagus on one of the short sides, that is Artemis during her bath, evokes the tragic death of Acteon, who was spying on the goddess and was then published for his act of hybris, and died young. Hippolytus, Phaeton, Acteon, Patroclus, all heroes who died in young and at tragic events: possibly functional references to the youth of Timios.

In general this lid panel from Ain Hofra seems to have been specifically planned in all its details, with a precise metric composition of the two figurative alae, corresponding directly to the poetic metric of the inscription. Looking carefully at the best preserved ala of the panel, that is the A (Fig. 1), the scenes seem to be organized in a sort of rhythmical iconographic composition with groups of figures characterizing three main scenes, in a sort of graphic transposition of the hexameter. Each lateral ala of the panel then presents 3 scenes/iconographic pedes: which are characterized by an increasing rhythm and tension towards the centre, in both cases culminating with the representation of Mithras, as moschophoros in one case (in the ala C, Fig. 3) and just after the tauroctonia in the other case (in the ala A, Fig. 4). This rhythmic and strictly metrical organization of the scenes-pedes is quite evident in ala A (Fig. 4), which is more complete: the oblique elements, such as the sticks of Saturnus and of Venus, the spear of Mars and the possible caduceus of Mercurius, all represented as inclined in the same way, divide the scenes in hemipedes and mark the levels of the Mithraic initiation. Similarly, ala C (Fig. 3) of the panel, although very fragmentary, seems to be organized in a similar metrical way, culminating in the representation of Mithras taurophoros during the transitus. In this metrical organization of the panel, the central section, with the inscription in tabula ansata and the Nikai, were then the poetic cesura of the ‘figurative verse’.

To conclude as Horace would say: pedibus claudere imagines instead of pedibus claudere verba (Hor., Sat., 2, 1, 28.)

Appendix A: Epigraphic study of the Tabula ansata

Stefano Struffolino

As already well explained in the text of the present paper, the inscription on the lid is enclosed in a tabula ansata, whose edges are embellished with fine mouldings.Footnote 11

The habit of framing in this way the epigraphic surface is well attested in Hellenistic and Roman times, and with particular frequency during late antiquity and in Christian epigraphy (Guarducci Reference Guarducci1967, 446). As is known, this is a layout whose original function is already attested in the Archaic period and in the Greek context, often shaped as single tablets, forged in bronze or carved in wood, to be applied on a support through two holes placed in the centre of the ansae, or in other places on the artifact. This model then found success as an ornamental epigraphic field for inscriptions created in a decorative framework for architectural contexts or in sculptural reliefs and mosaics: a use and a stylistic technique that have persisted throughout the history of epigraphic production, up to the modern era.Footnote 12 Di Stefano Manzella, precisely in relation to the arrangement of the inscriptions on the lids of the sarcophagi, speaks of ‘specchio di corredo’, functional inclusion in a balanced relationship with the decoration, often canonized and, not infrequently, a sign of serial productions (Di Stefano Manzella Reference Di Stefano Manzella1987, 100, 117–120). Examples of Cyrenaic inscriptions written in tabulae ansatae are not rare and all date to the Imperial era; for compositional interest we note the epitaph for a gladiator, paleographically dated between the second and third centuries AD, now in the museum of Ptolemais and probably from the western necropolis. The tabula ansata with the inscription in this case it is part of a stele and is placed under a niche containing a figured relief, presumably a portrait of the deceased (GVCyr018).Footnote 13 In the mosaic composition we then find the inscription in the triclinium room of the house of Leukaktios in Ptolemais, datable to the first half of the third century AD (Olszewski and Zakrzewski Reference Olszewski, Zakrzewski and Şahin2011, 665–674); and the one, always on the floor, from the basilica of qaṣr lībyā, of Justinian age (Reynolds Reference Reynolds, Alföldi-Rosenbaum and Ward-Perkins1980, 145–148).

The text of the sarcophagus epitaph can be transcribed and interpreted in this way (as also mentioned above in the contribution by Catenacci, Domenicucci, Menozzi):

Τɛίμιέ μοι | χαίροις καὶ | ɛἰν Ἀΐδαο | δόμοισιν

‘Timios, my dear, might you be happy even in Hades’ houses!’

The elegant layout is enriched by the presence of four hederae distinguentes: at the end of the first line, in the middle of the second line and at the beginning and end of the third. The shape of the letters is also worthy of particular attention: well engraved, apicated and with a paleography that presents interesting peculiarities that it is good to discuss in detail, as they can prove to be useful for chronological purposes.

Apart from the alpha with the broken bar and the right upright stretched upwards, and the rho with the rounded eyelet downwards – typical of Hellenistic-Roman writings – we immediately detect the rhomboid omicron (or ‘diamond-shaped’), characteristic of the “angled” style: an archaizing shape that comes into vogue especially from the middle of the second century AD.Footnote 14

Also the epsilon presents the central arm ‘dovetail-shaped’, whose origin, in the epigraphic practice, is certainly to be found in a stylistic extremization of the apicature of the stroke itself, which completely replaces the horizontal line. Identical parallels are not known to me in Cyrenaic inscriptions, but some cases of orthogonal epsilon with a conspicuously apical central stroke are found, for example, in Cyrene and Apollonia between the late Republican period and the early Imperial age (Reynolds, Apollonia 10, pl. XL; Gasperini Reference Gasperini1967, 53–64). The shape attested in this inscription, which therefore appears as a later evolution, finds a parallel – together with the rhomboid omicron – in a small Christian tombstone from the lower Moesia, dated to the first decades of the fourth century AD (Guarducci Reference Guarducci1978, 360–361, fig. 103). Instead, in the Christian epigraphy of Cyrenaica the lunate form of the epsilon is more common (where the orthogonal shape does not appear), as attested by various examples, among which a beautiful tabula ansata which is part of some fragments of a reconstructed marble panel found in 1934, in the cistern of the House of Hesychius at Cyrene (SEG XVIII 752 = Ward-Perkins and Goodchild Reference Ward-Perkins, Goodchild and Reynolds2003, 173, 3, i. For other examples see Ivi, passim, and Reynolds Reference Reynolds1960, 284–294).

Regarding the interpretation of the text, its fascinating literary parallels and the rare name of the deceased (see above for discussion); here we can add that in Cyrenaica we find at least two similar anthroponyms: a Τιμὼι daughter of Τιμοκλɛῦς, from an epitaph of the second half of the fourth century BC from Cyrene (IGCyr135000), and an Ἀναχαρήνα Τɛιμώ, from the stele of the subscriptions of the priestesses of Artemis (end second century AD), published by Silvio Ferri in 1926 (SEG IX 176, 16).

Furthermore, it seems pertinent to observe that searching in the epigraphic repertoires, where similar formulas in reference to the residences of Hades are not uncommon (see also discussion above), we also find an example where the term τίμιος occurs, in the second century BC, not as an anthroponym but in the proper sense of ‘honored’: it is a sepulchral epigram from Maroneia, whose last verse reads as follows: ɛἴ τι καὶ ɛἰν Ἀΐδηι τίμίον ἐστι βροτοῖς (I.Aeg. Thrace E215, ll. 910).

Before concluding this epigraphic appendix, however, it is necessary to add some important considerations that seem to emerge from the analysis of the engravings performed with the aid of computerized image filtering techniques (see Fig. A.1): the letters with which the first line is written appear slightly larger than those of the following lines, which could also simply indicate the desire to highlight the name of the deceased; but the section of the engraving seems triangular, unlike the round one recognizable for the other lines. This supposes two different moments of realization of the text and confirms the statement by Di Stefano Manzella (Reference Di Stefano Manzella1987, 100, 117–120) about the serial production of these texts with the formulas mentioned above, and perhaps already in an atelier near the marble quarry, which in this case seems to be the island of Thasos (see the appendix about the geological analysis, in Appendix B by Agostini). At a later time the buyer, once the piece arrived at its destination, could have completed it, thanks to a local craftsman, with the insertion of the name of the deceased. Even the hedera at the end of the first line is visibly made with a more subtle incision, and not with the same chisel as the other hederae; it is also smaller and asymmetrical in relation to the text.

Figure A.1. Images from the remote sensing of the inscription (by O. Menozzi).

The use of four different tools seems to emerge from the analysis of this inscription: the first one for the engraving – certainly in loco – of the first line; another for the following lines according to a probably pre-ordered model, and another two respectively for the first hedera and for the following three. In this regard, it should not be surprising that for the decorative elements, with more sinuous lines, tools other than those used to engrave letters were preferred; possibly we can think of a strap drill.

However, we cannot ignore the fact that the peculiar style of the letters is kept identical throughout the inscription, with considerable attention to the aesthetic coherence of the final work. Also in consideration of this evidence, the crafting of the tabula in two different places, remains a pure hypothesis, which does not exclude the possibility of its preparation in the officinae lapicidiariae of Cyrenaica,Footnote 15 perhaps in several stages and by different workers. On the other hand, the connection, apparently misleading, between the Mithraic context of the scene carved on the sarcophagus and the mention of ‘Hades’ houses’ in the inscription, has already been highlighted in the text of this article: the Iranian god of light illuminates the chthonic cavities where his cults were practised, raising the souls of his initiates to the sky and the saving light of truth.

To close the discussion on this inscription with the necessary chronological considerations, we can see how, in addition to the stylistic elements, as already pointed out, the paleographic ones also seems to suggest dating subsequent to the middle of the second century AD, but it does not go too far beyond the first decades or the middle of the third century; which seems to coincide very well with what can also be seen from the analysis of the remains of the surrounding figurative relief.

Appendix B: Brief notes on the marble of the lid

Silvano Agostini

MAIN PATTERN: Middle-grained white marble with quite evident light grey sections.

PATINA: greyish white patina, with areas with reddish residuals of the local reddish soils and of black areas due to different stratigraphic layers.

PRESERVATION: fragmentary. Presence of concretions of lamellar carbonate, probably due to some localized treatment of the surfaces; concretions of oxalates and of calcium carbonate which present a granular pattern and seem to be quite discontinuous and overlapping the lamellar carbonate concretions. It may depend on the stratigraphy.

Superficial flaking in some of the fragments which show more closely the pattern of the marble, below the polishing.

SUPERFICIAL TREATMENTS AND TOOL MARKS: the final polishing seems to be quite accurate and smoothed. Different kinds of chisels have been used, of different thickness and also presenting two different kinds of spikes, that is a triangular tip and a flat and trapezoidal one. Moreover, for the single holes a chisel with a deeper rounded tip has been used. Also the use of the running drill is attested, probably used not in perpendicular, but used with a slight degree of inclination.

THE TYPE OF MARBLE. In several fragments it is possible to analyze and identify the granulometry of the calcite crystals. Through the analysis and the imaging, before the next direct steps with digital microscopy on the fragments, it is quite evident that the M.G.S. value is between 2.70 and 3.00 mm. Some specific morphologies of the crystals are typical of the dolomites. Fabric: heteroblastic with a mosaic structure and sutured contacts.

On the basis of these very preliminary analysis it seems to be possible that the provenance of the marble is Thasos and in particular from the cave located at Vathy Cape (cfr Thasos Aliki).

Appendix C: The context: Ain Hofra and TOMB A

Eugenio di Valerio

The territorial context

Wadi Ain Hofra (http://www.slsgazetteer.org/1462/) is located to the east of the ancient urban context of Cyrene, about 1 km to the south of the Temple of Zeus Olympios and within the section East I of the necropolis. The geomorphology of the valley has been determined by the phenomena of erosion due to the flowing of the waters from Karst sources which are located at different levels of the alek (in Arabic it means the beginning of the inlet of the valley). The place-name including ain (that is source) attests this large presence of water, through the Arabic-maghrib linguistic root.

The area is today apparently quite marginal, but in antiquity was close to the town as well as to the main monumental contexts and to the southern section of the Hellenistic city wall (Fig. C.1). It consists of the enlargement of the defensive system of the town, which dates to the second century BC, and it is also the maximum expansion of the urban context, which continued up to Roman times. In this period Cyrene includes an area of 130 hectares, which were organized into seven quarters, and regularized by terraces and a road system closely related to the phases of enlargement of the site. The frequentation of the area of Ain Hofra is attested already in early periods within Cave W1, which presents also prehistoric phases. The use as a funerary context and as a sanctuary is attested since the late archaic period by tomb E24 (Cassels Reference Cassels1955): a chamber tomb with an external portico, presenting two stylized columns or pilasters with Aeolic capitals carved in low relief, which dates to the sixth-century BC (Thorn Reference Thorn2005). This tomb, for its position and monumentality, represents one of the main archaeological remains of the wady.

Figure C.1. Satellite view of Cyrene: in blue the Hellenistic city wall; in red the main road network; in white the possible secondary network going to Ain Hofra (mapping by E.Di Valerio, image © Google Earth, GeoEye 2013).

The area is strongly characterized by ritual rock cut chambers and votive niches attesting its main meaning as an open air sanctuary where chthonian cults are attested, with a strong link to numerous subterranean water springs and funerary monuments (Menozzi Reference Menozzi2015; Reference Menozzi and Russo2016).

The upper part of the valley presents numerous votive niches with inscriptions attesting early cults ad religious activities, which were dedicated to the Heroes, in combination with Eymenides and Zeus Melichios (Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Bonacasa and Ensoli2000, Menozzi Reference Menozzi2015, Reference Menozzi and Russo2016). During the Hellenistic period, on the lower terrace of the valley, the cult of Ammon is attested (Menozzi Reference Menozzi, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006; Reference Menozzi2015). The ancient Teban God (Amon, Amun, Hammon; in Egypt also assimilated in Ammon-Ra) is here venerated in a local form of a ram, and not in the syncretistic Greek form of Zeus-Ammon (Menozzi 2011, 324–326; Reference Menozzi2015, Reference Menozzi and Russo2016).

Excluding Tomb E24, and other tombs closer to the roads going to Cyrene, the earliest funerary monuments in the area date to the fourth to third century BC; their location presents a certain distance with the core area of the sanctuary, probably for respecting the plots belonging to the sanctuary. Moreover, the burial of a possible priest of the cult of the Melichios has been found, on the eastern slope of the valley (Menozzi 2011, 325; Reference Menozzi2015), certainly suggesting the possible use of the burials around the sanctuary by priests and pilgrims devoted to these exclusive cults.

Probably some aspects of these cults have seen a long continuity, up to the Hellenistic and Roman periods, when the exploitation of the area for funerary purposes became more intense, with the construction of further tombs, both cut into the bedrock and built.

THE TOMBS A and C

In this monumental funerary context the tombs which have been named as Tomb A and C (Di Valerio Reference Di Valerio2015) are located, also known as Tomb of the Sarcophagi the former, and Tomb of the Sculptures the latter: two monumental ‘temple tombs’, which have been built in the second century AD.

Tomb A is centrally located on the upper plateau of Ain Hofra, facing the valley, the lower terraces of the Djebel Akhdar and the seacoast. The area was already used for burials, as attested by the remains of a small temple tomb (known as Tomb D), and a rock cut tomb dating to the late Hellenistic period (known as Tomb B). The latter tomb must have been quite monumental and was created by carving directly on the limestone bedrock of the slope of the hill. It presents a large courtyard, a false façade and possibly loculi directly on the façade, while lateral rock-cut wings outlined the courtyards.

Tomb A was built on the eastern wing of Tomb B and used this wing as part of the masonry of the tomb on the western side of Tomb A.

Tomb B has never been excavated, except for a trial trench to understand the stratigraphy and typology of tomb. Tomb A has been excavated during the seasons of 2000 and 2001 by the archaeological Mission of Chieti University.Footnote 16

The plan

Tomb A is characterized by three rooms organized along a central axis (Fig. C.2):, creating a strong axial focus. The first room (A1), was probably a small pronaos or portico, which is not preserved and has been partially covered by a modern road, but the remains of columns (between the rooms A.1 and A.2) and of the stylobate, could be the only remains of the small portico and of the façade of the tomb. However, the columns could also come from the closeby Tomb C and reused in later times. The second and proper room (A.2) can be interpreted as the antechamber of the tomb and is characterized by a large squared plan (measuring mt 4 × 4, that is about 10 × 10 Ptolemaic/or Alexandrine feet, which was used at Cyrene in Hellenistic and Roman times). The third room (A.3) was the main funerary chamber, that is the ancient sepulcrum. It presents a rectangular plan (measuring 5,50 × 3,40 mt, that is 18 × 11 feet) and is located perfectly in an axial position with the rest of the structure. The back of this room has a very high podium, which was accessible through a three-stepped staircase, and was the base for the main sarcophagus (named find N.1, Fig. C.2), which has been studied and presented in other papers (Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti and Firpo2011).

Figure C.2. Plan of Tomb A (by E. Di E.Di Valerio and AR. Santarelli).

On the back wall, within probably a niche, a female portrait statue (find. N.2, Fig. C.2) has been used as the ‘completing’ of this axial view, culminating in these sculptures as optical reference points for the architectonical arrangement of the tomb.

The passages between the rooms (A.2 and A.3), as the niche itself, were probably marked by arches, contributing to this axial optical perspective; the arches were made using opus latericium, as attested by the finds of conglomerates and bricks which have been found during the excavations (Fig. C.3).

Figure C.3. TOMB A: the remains of the arch during the excavation (photo archive of Chieti MIssion).

This structural feature finds parallels in a rock cut tomb in the western necropolis, the W107 (also known as Tomb of Grenna: Thorn and Thorn Reference Thorn and Thorn2008, 95–116), where arches in bricks, resting on pilasters, marked the entrances to the three rooms where the sarcophagi were located.

The main sarcophagus on the podium of the sepulcrum in Tomb A was a woman, and the tomb was probably built for her death, as suggested by the emphasis given to this burial and to her splendid Sarcophaus neo-Attic in style and in Penthelic marble. However, another two burials were then added in the room, along the western side of the funerary chamber, where it has been possible to find a simpler burial in a pit grave and then, above this burial, another podium was built in ashlar masonry as a base for a second neo-Attic sarcophagus (find n. 3, Fig. C.2).

The building technique

Tomb A was built using large regular blocks of local limestone, using ashlar masonry technique with angular alternating chains of blocks to reinforce the structure. The blocks have been quarried directly from local sources; even the lower part of the basement of the tomb has been madedirectly from the local bedrock. Moreover, the foundations are dug directly into the bedrock and reinforced with limestone flakes bound by mortar.

The walls of the blocks are organized alternating orthostates and diathones, without any use of mortar or concrete as a binder. The lower part of the masonry is characterized by a double course of diathones for marking the basement of the walls. Moreover, the blocks do not show any use of metal block-ties for joining the layers of blocks.

The external appearance of Tomb A was characterized by a portico in antis, on a low podium, made of two rows of regular blocks, which was used as a krepis and which presents in the lower part a double ionic moulding alternating a tenia, double torus and a scotia (Fig. C.4). The moulding runs around the portico and along the façade shows angular lesenae and central semi-pillars, creating the effect of a tetrastyle façade (Fig. C.5).

Figure C.4. Tomb A: view of the internal walls of the antechamber and of the sepulcrum.

Figure C.5. View of Tomb A (photo archive of Chieti mission).

The blocks of masonry widely attest the use of ferrei divaricate to lift and support the heaviest elements during the building works, such as architraves, geison and so on.

The metric system which has been used for the monument is the so-called ‘alexandrine foot’, measuring 30.78 cm or the Ptolemaic foot of about 30.80 cm, which are extremely close and closely related.

Internal wall coverings and decorations

The tomb was decorated internally by different typologies of coverings. The walls of the antechamber (A.2) and of the funerary chamber (A.3) present a fine smoothed white plaster, probably painted. The parastae (half pilasters/semi-pilasters) at the entrance of the funerary chamber (A.3) were completely covered by polychrome marbles.

The two podia (basements) of the sarcophagi present a similar decoration with marble slabs. In fact, evident remains on the blocks of holes for clamps attest their use for supporting marble slabs belonging to opus sectile for walls (Fig. C.6). The clamps were probably hooked elements in bronze, which were fixed on the wall using mortar within holes of about 2–3 cm. The marble coverings of the walls were not limited to slabs, but must also have been elaborate sectilia, with geometric emblemata including both linear and curvilinear elements. Numerous fragments of this decoration have been found during the excavations (Fig. C.7), but in a secondary deposition, so it is quite impossible at the moment to understand the patterns of the opus sectile. What can be considered here is that the different typologies of the marbles which were employed (the archaeometrical analysis are now in progress), and the different thickness of this marble listels and elements may suggest an elaborated pattern. In particular, some thin elements, even smaller than 1 cm were probably used for filling the spaces which were carved in larger slabs, in a sort of cloisonné decoration. Close and significative parallels for the composition of these marble emblemata can be found, in the opus sectile of the pavements of the House of Jason Magnus at Cyrene (Mingazzini Reference Mingazzini1966, 44–47; Luni Reference Luni, Bonacasa and Ensoli2000, 96–99; Lazzarini Reference Lazzarini2004, 131–134). Outside Cyrenaica, specific parallels are preserved in marble decorations of Villa Adriana (De Franceschini Reference De Franceschini1991; Guidobaldi Reference Guidobaldi1994). On the basis of these parallels, it is possible to suggest some possible reconstructions of the decorative motifes of the emblemata in Tomb A (Fig. C.8).

Figure C.6. Tomb A: view of the internal walls of the antechamber and of the sepulcrum.

Figure C.7. The remains of the opus sectile and of the marble crustae which have been found in Tomb A (photo by E.Di Valerio).

Figure C.8. Possible reconstructions of the decorative patterns of the opus sectile (by E.Di Valerio).

Going to the pavements, Tomb A was probably completely paved by large rectangular marble and/or lithic slabs, which have been completely robbed and reused elsewhere in late antiquity. Remains of these slabs, in Pentelic marble, were still preserved just below the central and main sarcophagus, on the main podium. On the pavement of the antechamber as well, similar slabs decorated the central section of the room; what has been left today are just the mortar bedding of the slabs, but it is quite difficult to identify the typology of materials which have been used here. From a metrical point of view, it is possible to find three different modules which recur regularly in the central area, while the perimetral strip, about 2 feet thick, does not present remains of slabs and was probably characterised by low benches (Fig. C.2).

Entablature and roof

Concerning the entablature, the finds form the excavations are quite rare. Only a fragment of geison can be of some help: it consists of an ionic element which has been found between rooms A.2 and A.3 (Fig. C.9). The fragment is not very well preserved; its original location is probably attributable to the main gate of room A.2. The external appearance of the tomb was decorated by a Doric frieze; but it is difficult to reconstruct if it was limited to the façade or if was running all around the building. Corner pilasters and lesenae decorated the façade, and were crowned by capitals, which are not well preserved for reconstructing the original appearance.

Figure C.9. Tomb A: Architectural element (by E.Di Valerio).

The roof was built on a wooden structure with rafter beams resting on a ridge beam, which is closely linked to the tympanum (pediment) in limestone. This main skeleton was then supporting a regular wooden structure consisting of horizontal strips, which were parallel to the eaves and rafters inclined according to the slope of the roof.

The external covering of the roof was carried out using plain roof tiles, without thickened borders, and measured in pedales (about 30 × 30 × 3,5 cm). These typese of tiles were used, within the western Roman provinces, for the construction of both the vaults and the wall coverings; but more frequently can be found as part (the base or the ending) of the suspensurae of the baths (Cerdán Reference Cerdan, Arce, Ensoli and La Rocca1997, 378–379). In the case of Tomb A of Ain Hofra, as also attested for the closeby Tomb C, these elements were used to line the roof.

The main finds of the tomb

Both Tombs, A and C, must have been magnificent, considering their monumentality, marble and plaster decorations, as well as the numerous marble sculptures in both of them. In order to contextualize the lid properly, which is presented in this article in the main contribution (above), a catalogue of the sculptures from Tomb A is presented here. The level of the sculptures and the large number of marbles which have been used both for the sculptures, as well as for the decorative apparatus of the tomb, help us to understand the social status of the owners of these two monumental tombs at Ain Hofra, as well as their cultural level and religious beliefs.

Find n.1- Attic Sarcophagus with Dionysian Thiasos with lid in form of kline (Fig. C.10)

Location: it was located in central position on a high podium, in the room A.3, that is the funerary chamber. At the moment it is preserved in the exhibition in the Pavilion of the Sculptures, Museum of Cyrene.

Figure C.10. The Sarcophagus with Dionysiac thiasos and its lid (Archive of Chieti Mission).

Material: Pentelic marble

Measurements: Sarcophagus: h.110 cm, 225 cm long, lateral sides 85 cm large. The lid: h. 95 cm

State of preservation: it has been found almost complete. Just one corner is damaged, probably because it was broken in antiquity for looting the tomb and using a lever to move the lid, without removing it because it is too heavy. Moreover, the main frontal side has a break in the central area, which has been restored by technicians of the local DoA of Cyrene (Said Farag, Saed Alannabe and Abdulrhim Sheriff SAad). For the lid, the head of the male figure was broken and it has been restored by the technicians of the DoA. While the female figure is completely lacking the head, which has never been found.

Dating: last quarter of the second century AD (Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti and Firpo2011, 203).