Introduction

Human sacrifice relates to some of the most central political and societal questions of human history, as well as pressing issues on security, the current war on terror and modalities of power in modern liberal societies. Critical contemporary phenomena, such as suicide bombings, often defy easy sociological or psychological explanations, but may be motivated by a propensity for self-sacrifice and the sacrifice of others. In this sense, human sacrifice is well attested throughout history (Campbell Reference Campbell2014; Watts et al. Reference Watts, Sheehan, Atkinson and Gray2016; see also Figure 1), and policy-makers and the public today are constantly exposed to its realities. At the same time, the term ‘human sacrifice’ is something of a floating signifier (Smith Reference Smith, Patton and Ray2000; Girard Reference Girard2016; Schwartz Reference Schwartz2017); it is difficult to define, with some anthropologists arguing that human sacrifice is nothing but a mythical Western construct, ascribed to ‘others’ as a way of demonising them (Bremmer Reference Bremmer2007).

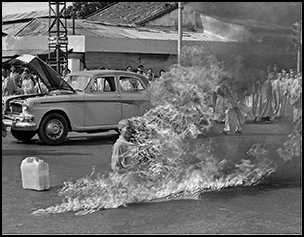

Figure 1. From upper left to lower right corner: Thích Quáng Đúc (1963); the French Revolution (1789–1792); the Tollund Man bog body (fourth century BC); foreign fighters (2015) (photographs from Wikimedia commons).

This project, ‘Human Sacrifice and Value’, therefore seeks answers to two fundamental questions. The first is what is human sacrifice and how does it differ from other forms of violence? The second is why do people sacrifice human lives?

The point of departure for this project is that human sacrifice cannot be studied in isolation or on any essentialist terms, as it previously has been (Bourdillon & Fortes Reference Bourdillon and Fortes1980). Within archaeology, history and anthropology, for example, violence has been frequently explained by situating it within a ‘sacred vs profane’ dichotomy, with little attention given to the correlation—and even historical co-dependence—between the two. This has often led to blind alleys and essentialised categorisations that have reduced the epistemological complexity of these phenomena, and made it difficult to compare them across time and space.

In this project, we regard human sacrifice as any kind of violence that people inflict on one another when sanctioned or sanctified, e.g. by social authority, and with explicit reference to a higher purpose or higher authority. By exploring the ever-changing boundaries of human sacrifice and comparing it with acts of more common forms of profane violence, such as murder, political violence, torture, terrorism, warfare and genocide—or even self-sacrifice—it is our hope that the importance of the phenomenon can be better comprehended. This requires a much more critical exploration of conventional theories of human sacrifice, with renewed analyses of why and how it has occurred throughout human history. It also demands more direct engagement with the pervasive ramifications of human sacrificial practices today. Such acts continue to be manifested and often publicly conceptualised in secular forms of violence such as judicial executions (Halbertal Reference Halbertal2012), and in acts of religious martyrdom such as extremist suicide bombings.

By introducing into this theoretical arena a series of empirical examples of sacrificial rituals related to the substitution and transformation of socially recognised and culturally relative notions of the value of human life (Willerslev Reference Willerslev2009), we wish to challenge remaining essentialist notions of human sacrifice. We also strive to introduce a lens through which to conceptualise this fundamentally multifaceted and dynamic phenomenon; one that considers the complex relationship between human sacrifice and other forms of violence.

Methodology

The project adopts a longue durée perspective on human sacrifice, ranging from the Neolithic to the present day—primarily in Scandinavia and Northern Europe. Here, three historical periods have been identified wherein human sacrifice is particularly evident, including the Early Iron Age (700 BC–AD 400), the Viking Age to early medieval period (AD 800–1200) and contemporary twenty-first century society.

The project adheres to a set of procedures in order to ensure coherence and complementarity of studies across the three historical periods. We have carried out an extensive literature review, exploring the dominant views and theories on what constitutes sacred violence and the reasons behind it. A rigorous quantitative and qualitative data collection effort provides the empirical basis for the three case studies, based on published and unpublished archaeological, ethnographic and historical archives, ethnographic fieldwork and policy records. Data are coded on the basis of suitable units of analysis, ultimately with the objective of revealing the values underpinning various human sacrificial traditions and how they emerge and are subverted and substituted over time in different historical contexts. Examples include: the emergence of the ritual killing of humans in wetlands during the Iron Age, which later substitute clothes and ritually damaged weaponry for the actual human life (Løvschal & Holst Reference Løvschal and Holst2018); transformation of the sacrifice of Christ into tangible and monetary values (Gullbekk Reference Gullbekk, Kershaw and Williams2019); and ideological and religious emotions turned into symbolic and performative violence (Johansen et al. Reference Johansen, Weiss, Sandrup and Grassiani2018).

Quantitative statistical approaches in the selected case studies generate further hypotheses about ontological shifts and cultural transmission to explore how and why human sacrificial practices emerge and disappear again. In the centuries around the birth of Christ, for example, increased political pressure and unpredictable raids towards the northern bounds of the Roman Empire appear to have played a critical role in the growing display of violence penetrating the sacred realm of Southern Scandinavia. This was manifested in the systematic destruction and dismantling of weapons, animals, humans and artefacts deposited in wetland contexts.

A series of case studies outside the project's specific historical and geographic foci offer perspective. Examples include epistemologies and practices related to counter-terrorism and the prevention of religious sacrificial violence; sacrifice in the former Soviet Union and during the Russian Revolution; Aztec sacrifice; and Biblical and Quranic exegesis.

The project encompasses anthropologists, archaeologists, historians, numismatists and heritage specialists. It is hosted by the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo in Norway, with key collaborators at Aarhus University in Denmark and the National Museum in Copenhagen. The project is financed by The Research Council of Norway (FRIPRO HUMSAM, project 275947). Additional radiocarbon samples have been funded by the Material Culture and Heritage programme, Aarhus University. The project ultimately aims to generate a greater working—and theoretical—knowledge of the nature of human sacrificial violence, which will inform archaeologists, historians and anthropologists, as well as the wider public, who are regularly confronted with the very real consequences of human sacrificial violence.