The comorbidity of severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, with personality disorder is common and is one of the most frequent dual diagnoses found in clinical practice. Between 30 and 60% of those with psychotic disorders have a personality disorder also (Reference Casey and TyrerCasey, 2000) and the proportion tends to be higher in in-patient populations (Reference Cutting, Cowen and MannCutting et al, 1986). The outcome of those with comorbid personality disorder is generally less good than the outcome of those with single mental state disorders, with less improvement in symptoms, poorer quality of life and greater dissatisfaction with treatment after 2 years (Reference Tyrer and SeivewrightTyrer & Seivewright, 2000). Despite these important clinical correlates, these comorbid conditions are not often recognised in ordinary practice, mainly because the identification of personality disorder is often difficult in patients who have widespread abnormalities. In the case of schizophrenia, these may overflow into the personality domain and lead to poor reliability of assessment (Reference Tyrer, Strauss and CicchettiTyrer et al, 1983).

There is now a general belief that most patients with severe mental illness can be treated largely in the community, with only brief periods of admission. However, for those with gross personality disorder who are treated at special hospitals a very much longer period of treatment is common. We felt that it might be valuable to examine the outcome of those with comorbid severe mental illness and personality disorder, to determine whether there were important differences between the effects of different service intervention policies.

METHOD

The relevant data from three studies of different models of care, carried out in west London (Paddington and Brent), are summarised in Table 1. In each of the studies (all randomised controlled trials) a community-focused service was compared with a more hospital-focused or standard service, which had fewer community resources. The time span of the three studies was 8 years and during this period the standard service steadily improved in its community orientation, so there was an expectation that differences would become fewer over time. The overall findings supported this view, with the early study showing the strongest differences in favour of the community service (Reference Merson, Tyrer and OnyettMerson et al, 1992).

Table 1 Three randomised controlled studies of models of community management in severe mental illness

| Authors | Main comparisons | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Merson, Tyrer and OnyettMerson et al, 1992; Reference Tyrer, Merson and OnyettTyrer et al, 1994 | Community team focused on early intervention v. hospital treatment | Clinical symptoms, social functioning, personality status, duration of in-patient care |

| Reference Tyrer, Evans and GandhiTyrer et al, 1998; Reference Gandhi, Tyrer and EvansGandhi et al, 2001 | Community-focused care programmes v. standard care programmes | Clinical symptoms, social functioning, personality status, duration of in-patient care, contacts with police over 1 year |

| Reference Burns, Creed and FahyBurns et al, 1999; Reference Tyrer, Manley and Van HornTyrer et al, 2000 | Intensive v. standard case management | Personality status, duration of in-patient care |

In this current set of investigations, however, all effects were examined between those with and without personality disorder; and the influence of personality status on response to each service intervention (i.e. the interaction between personality and service type) was recorded. This was part of a Cochrane systematic review first established in 1997 (Reference Tyrer, Coid, Simmonds, Adams, Duggan and de Jesus MariTyrer et al, 1999). The only specific hypothesis tested was that those with comorbid personality disorder and severe mental illness would have a better response to focused community treatment, as they are generally considered to be ill-placed in hospital.

Patients, assessments and procedures

All patients in two of the studies had a psychotic illness with frequent hospital admissions, and in the third (Reference Merson, Tyrer and OnyettMerson et al, 1992) the patients were emergency presentations to the psychiatric services; 70% of these had schizophrenia or affective disorders. Assessments of clinical symptoms in all studies was with the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale (CPRS) (Reference Åsberg, Montgomery and PerrisÅsberg et al, 1978). Social function was recorded with the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ) (Reference Tyrer, Peck and ShapiroTyrer, 1990) in two of the three studies reported here.

The procedures for randomisation and assessment intervals differed. In one study, randomisation took place at the point of presentation as an emergency (Reference Merson, Tyrer and OnyettMerson et al, 1992), with assessments at baseline and after 2, 4 and 12 weeks. In the second study, randomisation took place at the time when in-patients were assessed as fit for discharge (Reference Tyrer, Evans and GandhiTyrer et al, 1998). In the UK700 study, randomisation took place at the point of discharge and a follow-up (Reference Creed, Burns and ButlerCreed et al, 1999).

In all three studies personality was assessed using the Personality Assessment Schedule (PAS) (Reference Tyrer and AlexanderTyrer & Alexander, 1979) although in the UK700 study a shorter version, the Rapid Personality Assessment Schedule (PAS—R) (Reference Van Horn, Manley and UkoumunneVan Horn et al, 2000) was used. In all analyses a simple distinction was made between personality disorder and no personality disorder. The threshold for the diagnosis of personality disorder using the PAS is a little higher than that for ICD-10 personality disorders (Reference Tyrer, Merson and OnyettTyrer et al, 1994), which equates to the level of personality difficulty in a dimensional scale (Reference Tyrer and JohnsonTyrer & Johnson, 1996).

RESULTS

The findings from the first two studies are summarised in Tables 2 and 3. In the first study, the admission of all patients was reduced markedly in the community service, but this was achieved at the expense of a poorer outcome in those with personality disorder. This was most marked for social function and depressive symptoms. In the second study, there were no important differences in symptomatic outcome, but those with personality disorder were not kept out of hospital to a significantly greater extent. However, in this study there was greater improvement in those with personality disorder treated in the community-oriented service. Meta-analysis of the proportion of patients making a significant improvement (to a CPRS score of 10 or less) showed 54% of personality disorders improving in the community group compared with 19% in the hospital group (P < 0.002) (Table 4).

Table 2 Comparison of outcomes of comorbid and single diagnoses in community- and hospital-based teams (Reference Merson, Tyrer and OnyettMerson et al, 1992): trial of patients presenting as emergencies (n=100)

| Variable1 | Community service | Standard service | Superiority of community service | Significance of interactions between service, personality and time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of trial | Baseline | End of trial | |||

| CPRS, no personality disorder | 34 | 20 | 26 | 22 | 10 | P=0.13 |

| CPRS, personality disorder | 33 | 24 | 32 | 25 | 2 | |

| MADRS, no personality disorder | 25 | 13 | 20 | 17 | 9 | P<0.02 |

| MADRS, personality disorder | 23 | 18 | 23 | 18 | 0 | |

| BAS, no personality disorder | 18 | 12 | 16 | 12 | 2 | NS |

| BAS, personality disorder | 22 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 4 | |

| SFQ, no personality disorder | 10.4 | 7.7 | 11.1 | 8.8 | 0.4 | P=0.082 |

| SFQ, personality disorder | 12.9 | 12.8 | 12.4 | 9.3 | -3.0 | |

| Patients admitted, % (n/N) | ||||||

| No personality disorder | 17 (5/29) | 25 (9/36) | 8 | χ2=0.21,3 P=0.65 | ||

| Personality disorder | 12 (2/19) | 44 (7/16) | 32 | χ2=3.4,3 P=0.06 | ||

| Mean duration of admission, days during | ||||||

| 12 weeks4 | ||||||

| No personality disorder | 1.2 (n=29) | 8.4 (n=36) | P<0.05 | |||

| Personality disorder | 1.1 (n=19) | 11.3 (n=16) | ||||

Table 3 Summary of results of trial of community-orientated and hospital-orientated care programmes separated by comorbid personality disorder with assessments at baseline and after 1 year (Reference Tyrer, Evans and GandhiTyrer et al, 1998; Reference Gandhi, Tyrer and EvansGandhi et al, 2001) (n=138)

| Variable | Community service | Standard service (hospital) | Relative difference (community minus hospital) | Significance of differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of trial | Baseline | End of trial | |||

| CPRS, no personality disorder | 15.1 | 16.3 | 15.6 | 15.6 | -1.2 | NS |

| CPRS, personality disorder | 17.7 | 13.9 | 14.8 | 18.2 | 7.2 | |

| SFQ, no personality disorder | 7.7 | 7.9 | 9.8 | 9.0 | -1.0 | NS |

| SFQ, personality disorder | 12.6 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 9.2 | 0.9 | |

| Patients admitted, % (n/N) | ||||||

| No personality disorder | 59 (24/41) | 74 (34/46) | χ2=2.3, P=0.13 | |||

| Personality disorder | 73 (22/30) | 62 (13/21) | χ2=0.75, P=0.39 | |||

| Mean duration of admission, days in 1 year1 | ||||||

| No personality disorder | ||||||

| Paddington | 10.1 (n=27) | 22.0 (n=29) | P < 0.02 (site difference only) | |||

| Brent | 34.5 (n=14) | 34.8 (n=17) | ||||

| Personality disorder | ||||||

| Paddington | 24.0 (n=23) | 20 (n=17) | ||||

| Brent | 81.1 (n=7) | 65.8 (n=4) | ||||

Table 4 Meta-analysis of studies 1 and 2 showing greater improvement in those with personality disorder in community-oriented service, measured by proportion of patients whose symptoms had been significantly relieved

| Variable | Community service (n/N) | Hospital service (n/N) | Combined effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients admitted | |||

| No personality disorder | 29/70 | 43/82 | Z=1.66; P=0.10 |

| Personality disorder | 24/49 | 20/37 | Z=0.68; P=0.5 |

| Drop in CPRS score to < 10 | |||

| No personality disorder | 13/28 | 21/26 | Z=2.3; P=0.02 |

| Personality disorder | 15/28 | 5/26 |

In the second study there was a major shortage of beds in the Brent area, and for much of the period of the study a significant proportion of admissions were extra-contractual referrals to different hospitals (Reference Tyrer, Evans and GandhiTyrer et al, 1998). This probably accounted for the greater length of admission of Brent patients; those with personality disorder, in particular, had very long periods of in-patient treatment in the year after recruitment to the study. The interaction between personality status and site of service was significant.

In a separate part of the study, the number of contacts with police were recorded in the year of the study. Of 26 incidents involving 16 patients with the police, most were found in those with personality disorder within the flamboyant (cluster B) grouping. These were significantly more common in patients allocated to community-oriented management (Reference Gandhi, Tyrer and EvansGandhi et al, 2001). All but two of these incidents were in the Paddington component of the project, significantly more than one would expect by chance (χ2=4.7 (after Yates' correction), d.f. 1, P=0.03) and this is unlikely to be explained by demographic differences alone. It seems likely that the long period of in-patient treatment of those with the comorbid diagnosis in the Brent area reduced problems in the community and could be perceived as giving some protection to the public.

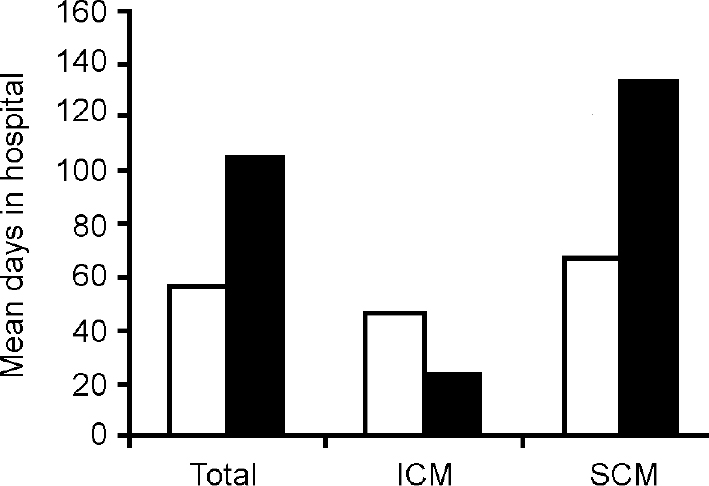

In the third study, there was an imbalance between the allocation of patients with personality disorder to intensive or standard case management, so that approximately only 1 in 4 of those with personality disorder were allocated to intensive case management. The small numbers made the interpretation of data difficult and there were no clear differences in any of the main outcome variables, with the exception of duration of in-patient care, the main outcome measure of the study. Those with comorbid personality disorder and psychosis had a shorter duration of in-patient treatment in the 2 years of the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Mean days in hospital over 2 years for 145 patients (114 with no personality disorder (□) and 31 with personality disorder (▪). Shorter duration of hospital care for those with personality disorder treated by intensive case management (ICM) (n=8) compared with those treated with standard case management (SCM) (n=23, P=0.06 (for interaction)). Of those with no personality disorder, 59 and 55 were treated with ICM and SCM, respectively. (Data from Reference Tyrer, Manley and Van HornTyrer et al, 2000.)

DISCUSSION

The evidence base for interventions in comorbid personality disorder and severe mental illness is limited, and in a recent Cochrane review of the subject the only randomised controlled trials were those reported here. The three studies demonstrate four features:

-

(a) Aggressive community care may be successful in keeping these patients with dual diagnoses out of hospital.

-

(b) The price of this success is often more impaired social function in those who remain in community care.

-

(c) There may be greater risks to the public if community treatment for this group is pursued.

-

(d) When a community-oriented approach is pursued with less emphasis placed on keeping patients out of hospital, there are better outcomes, both for patients and in protecting the public.

The findings go some way in supporting the notion that personality disturbance is more important than mental illness state in determining disturbed and antisocial behaviour, and perhaps should be assessed more commonly in ordinary practice. Whereas violence in severe mental illness is the same for those treated by intensive and by standard case management (Reference Walsh, Creed and HarveyWalsh et al, 2001) the additional measurement of personality status adds an extra dimension. In the UK700 study, violent episodes were found to be more frequent in those with personality disorder (P. Moran, personal communication, 2002). What is abundantly clear is that treatment policies of those with comorbid personality disorder and severe mental illness should not be assumed to be the same as for those with severe mental illness alone, and that further work is needed on specific interventions for this group.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Patients with comorbid personality disorder and severe mental illness have worse outcomes if an aggressive community treatment policy is adopted that reduces admission to hospital to a minimum.

-

▪ The assessment of personality status in those with severe mental illness would help clinical management.

-

▪ The nuisance and distress created for the public by patients with comorbid diagnoses needs greater attention to reduce the stigma of mental illness.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The studies described, although using randomised controlled designs, were not hypothesis-driven and most analyses were post hoc.

-

▪ The studies were carried out in London at a time when bed pressures were very great, and this may have distorted generalisation of the findings.

-

▪ No acknowledgement was made of the implications of comorbid personality disorder in treatment policies, and the results might have been different if treatment had been adjusted accordingly.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by the North Thames Regional Research Committee and Central Research & Development at the Department of Health. We thank Dr Phil Harrison-Read and Dr Tony Johnson for assistance and advice.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.