Since the poem first came to scholarly attention in the early nineteenth century, it has been conventional to regard Beowulf as the apotheosis of the so-called classical alliterative long line. Every theory of Old English meter has been measured by the measures of Beowulf. But the date of Beowulf and the contours of alliterative verse history before roughly 950 are interdependent reconstructions. Is Beowulf metrically old or metrically conservative? And how old or conservative? The meter of Beowulf cannot be contextualized without first inquiring into the development of alliterative meter in the unreliably documented earlier period. Metrists have sidestepped the problem either by assuming an early date for Beowulf, which is circular, or by subsuming verse history in language history, which is a category mistake.

This chapter reviews some metrical tests thought to establish a very early date (before c. 750) for the composition of Beowulf. The first section charts the evolution of the alliterative meter, 950–1100, and adduces new evidence of synchronic metrical variety in this misunderstood period. The second section argues that previous studies have discovered a metrically old Beowulf only by reducing verse history to language history a priori. The dynamism of alliterative meter, demonstrable after 950 and presumable before 950, problematizes the methods by which metrists have sought to locate Beowulf in the early eighth century. A third section reviews and challenges four non-metrical arguments for a very early Beowulf. Together, the three sections demonstrate a key conclusion of the book as a whole: metrical form has a history of its own, which cannot be reduced to cultural, linguistic, political, or textual history. To the extent that verse history registers events in these other historical series – whether the circulation of legends, the loss of inflectional vowels, the conquest of a political territory, or the transcription of an exemplar – it does so through the medium of its own logic.

The Evolution of Alliterative Meter, 950–1100

Before evaluating the methods by which metrists have sought to reconstruct the shape of alliterative verse history before 950, it will be useful to trace the development of the alliterative meter after 950. Here I coordinate two synchronic systems of notation, one designed to describe the Beowulf meter and the other to describe the meter of Lawman’s Brut (c. 1200), in order to reveal the metrical regularity and historical dynamism of late Old English poetry. This newly precise description of alliterative verse history, 950–1100, aids in two essential tasks. First, it substantially revises received understandings of metrical form in the period. I show how scholars’ impression of a decadent late Old English meter results from an insufficiently diachronic perspective onto the alliterative metrical system. Second, the knowable history of post-950 alliterative verse acts as the best available control on inferences about the texture of verse history before 950. The next section brings both considerations to bear on the question of dating Beowulf on metrical grounds.

A richer historical perspective onto late Old English meter has been made newly possible by advances in the study of the Beowulf meter and the Brut meter. Nicolay Yakovlev, the author of a fundamental study of alliterative meter (still unpublished), discloses a new theoretical paradigm for Old English meter. Yakovlev dispenses with alliteration, secondary stress, feet, word boundaries, and the restriction to two metrical stresses and defines the half-line as a sequence of four metrical positions, either lifts or dips. By definition, no two dips can be adjacent, for in that case they would merge into a single dip. Where most previous commentators described Old English meter as accentual, i.e., based on the stress of individual words, Yakovlev describes it as morphological, i.e., based on the category membership of individual morphemes regardless of their position within the word. Eduard Sievers’s Five Types are replaced with eight permutations of lifts and dips in a frame of four positions:

| OE (Sievers) | OE (Yakovlev) | |

|---|---|---|

| A | = | Sx(x …)Sx |

| B | = | x(x …)SxS |

| C | = | x(x …)SSx |

| A/D | = | SSSx |

| D/E | = | SSxS |

| A/E | = | Sx(x …)SS |

| B/C | = | x(x …)SSS |

| A/D/E | = | SSSS |

To the basic four-position structure Yakovlev adds three more metrical principles: resolution and its suspension; prohibition of long dips in the third and fourth positions; and the ‘prefix license,’ whereby verbal prefixes and the negative particle ne may optionally be omitted from the metrical count. Each of these principles adds a minor complication to the way that Old English meter maps language onto metrical positions. Resolution and the prohibition against third- and fourth-position long dips already appeared in many prior theories of Old English meter; both are discussed in the Introduction. The prefix license represents Yakovlev’s original synthesis of diverse conclusions in previous scholarship. Many of these earlier discussions concerned ‘anacrusis,’ which referred to an extrametrical syllable before the a-verse. By offering the prefix license as a general principle of Old English meter, Yakovlev effectively reduces ‘anacrusis’ to the status of a special case.

Yakovlev’s morphological theory of Old English meter explains many mysteries, including why Type A is the commonest contour (it occurs in the most permutations); why it is impossible to tell whether verses like wyrd oft nereð belong to Type A or to Type D (both are SSSx) or whether verses like flod blode weol belong to Type D or to Type E (both are SSxS); why metrical resolution occurs indifferently under, and is suspended indifferently after, ‘primary,’ ‘secondary,’ and ‘tertiary’ stress (there is no metrical significance to these varieties of linguistic stress); why curiosities such as resolution, clashing stress, and the optional expansion of dips are permitted in the first place (the meter counts positions, not accentual rhythms); and why prefixes may count or not count in the meter (metrical value – stressed, unstressed, or omitted – is assigned morpheme by morpheme, not word by word or foot by foot). At last, the Five Types can be understood as “the epiphenomenal results of a simpler paradigm.”1 The occurrence of ‘secondary stress’ in Sievers Types C, D, and E follows from the structure of Old English words, but the metrical principles operate at a deeper level of abstraction. In the prominence it accords to the concept of ‘metrical position,’ Yakovlev’s theory draws on a long tradition of prosodic scholarship, stretching from Sievers to Thomas Cable; but the proposition that Old English meter was morphological, not accentual, is as original as it is clarifying.

Yakovlev’s generalization that Old English meter was morphological is both descriptively adequate and theoretically illuminating, but it does remain a generalization about a meter with at least three recognizable principles of organization: morphological, quantitative, and accentual. The Introduction summarized the importance of quantity in Old English meter: in this meter, the difference between a quantitatively long syllable and a quantitatively short syllable is metrically significant in the case of stressed syllables. Old English verse also shows a minor impulse toward accentual meter alongside the major impulse toward morphological-quantitative meter. The occasional metrical promotion of function words in order to make up the requisite four positions, e.g., Beowulf 22a þǽt hyne on ýlde, is one expression of an incipient accentual meter.2 Moreover, the morphological and accentual principles overlap in determining which words are eligible for metrical stress, since both principles can rely on the same hierarchy of grammatical class membership, in which content words outrank function words. The remainder of this section, along with Chapter 3, describes the formal processes by which a morphological-quantitative metrical system with minor accentual features developed into an accentual-quantitative metrical system with remnants of morphological organization. Chapters 4 and 6 move this narrative forward to the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries, when alliterative meter left quantity behind in the process of becoming more accentual. Thus the accentual principle represents a form of continuity in alliterative verse history, albeit one expressed much more forcefully in the second half of that history. For now, it is important to note that the evolution of metrical modalities in the alliterative tradition was more fluid than a single label (‘accentual,’ ‘morphological,’ or ‘quantitative’) can convey. Keeping this caveat in mind, the labels remain useful as schematic representations of long-term trends in versification.

Yakovlev’s decoupling of Old English metrical form from Old English linguistic form enables him to trace a developmental arc from the Beowulf meter to the Brut meter (and beyond: see Chs. 3 and 4). This accomplishment, too, had been unthinkable in previous statements of meter. Yakovlev finds five metrical patterns in the b-verses of the Brut, which are strongly reminiscent of the Old English patterns (p)Sx(x …)Sx, x(x …)SxS, and x(x …)S(p)Sx (Types A, B, and C in Sieversian notation), where ‘p’ marks a verbal prefix or negative particle omitted by the prefix license:

The innovative five-position pattern x … xSxSx (Yakovlev Type 2) could also have arisen by ignoring metrical resolution in the Old English patterns x(x …)SrSx and x(x …)SxSr (Types B and C), where ‘Sr’ marks a lift under resolution. Around 65 percent of Lawman’s a-verses take one of the five forms, as well, but the others are bound by few principles. Therefore, the following discussion focuses on b-verses.

Once connected with a morphological Old English meter, Lawman’s meter reveals processes of selection in alliterative verse history. The two-lift Old English patterns ((p)S(x …)xSx, x(x …)SxS, and x(x …)S(p)Sx; Sievers Types A, B, and C without ‘secondary stress’) are precisely the ones used by Lawman in the b-verse, with expansion of one expandable dip (Types 1–5). The decline of clashing stress in alliterative meter, long remarked upon by metrists, turns out to be a red herring. It was not clashing stress per se that was deselected from alliterative meter after 950, but b-verses with three or four lifts. The only logically possible four-position pattern with exactly two clashing stresses (x(x …)SSx, Sievers Type C) survived in the b-verses of Middle English alliterative poetry as Type 5. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Type 5 appears as a vestige of a morphological meter in a metrical system that had long since become accentual. Metrical vestige as a “historical residue” constitutes another of Yakovlev’s contributions to the conceptual vocabulary of early English metrics. “Given the rare opportunity to observe a cross-section in the history of a poetic tradition,” writes Yakovlev, “we always see ‘a work in progress’; the picture observed will always be inherently dynamic.”3 In building upon Yakovlev’s evolutionary model throughout this book, I seek to lend further specificity to the perception of an “inherently dynamic” configuration of metrical patterns in each phase of alliterative verse history.

A second newly visible “historical residue” is the appearance in post-950 alliterative verse of half-lines with three lifts and more than four metrical positions. In addition to the five two-lift patterns, Yakovlev finds that Lawman also composed three-lift verses constrained only by the avoidance of final long dips (as in all Old English patterns) and a minimum (but no longer a maximum) of four positions. Three-lift patterns occur commonly as a-verses and rarely as b-verses in the Brut. For the first time in the study of alliterative meter, three-lift verses in late Old English, Early Middle English, and Middle English alliterative verse can be explained as vestiges of a metrical system that counted positions rather than accentual stresses. Middle English metrists have always debated whether verses with three content words, e.g., Gawain 2a Þe borʒ brittened ond brent, should be scanned with two or three lifts. The proponents of two-lift scansion have made their arguments on a more or less synchronic basis, occasionally gesturing toward two-lift theories of Old English meter. Yakovlev settles the debate in favor of a three-lift scansion by engaging a historical perspective on the problem. He presents a non-beat-counting Old English meter and a non-beat-counting Middle English a-verse meter, but unlike proponents of a two-lift norm he also directly connects these two systems, and Lawman’s meter, in one centuries-long catena of metrical practice.

In what follows, I test Yakovlev’s metrical model on several late Old English poems not considered by him. By triangulating between the two moments in verse history represented by Beowulf and the Brut, it becomes possible to bring into focus the development of the alliterative meter after 950. Poems from this period include many datable compositions from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, not all of which have always been recognized as poems. Consider the b-verses of the Chastity of St. Margaret (1070–71), accompanied by Sievers and Yakovlev scansions jointly (quoted from Appendix A, no. 6):

Chastity, composed more than 100 years before the Brut, partakes of aspects of both synchronic systems represented by Sievers’s and Yakovlev’s metrical typologies. The lines characterized here as Types 3, 4, and 5 could be described, respectively, as the Old English patterns Sx(x …)Sx, x(x …)SxS, and x(x …)SSx (Sievers Types A, B, and C). But the tendency toward the two-lift, one-long-dip b-verse is already taking hold. The verbal prefix ge- in 4b may be omitted from the metrical count, as in earlier Old English verse (for Sievers Type A), or included in the count, as in later alliterative verse. The five-position pattern with no long dip (xSxSx) is particularly symptomatic of ongoing metrical evolution: this pattern had been unmetrical in the Beowulf meter (because it has five positions) and would become unmetrical again by the time of the Brut (because it lacks a long dip). The pattern xSxSx, which bears a certain similarity to the French-, Italian-, and Latin-influenced deductive English meters that had yet to be invented in the 1070s, was a pattern of avoidance in the b-verse for most of alliterative verse history. For a relatively short period, however, it was one way of resolving the conflicting demands of the outgoing four-position principle and the incoming lift-and-dip system.

Compare the first ten b-verses of the earlier Death of Alfred (1036–45) (quoted and numbered from ASPR 6):

| x x x x S S x | ||

| and hine on hæft sette | (5) | |

| x x x S x(x) p S | ||

| and sume mislice ofsloh | (4)4 | |

| x x S x(x)p S x | ||

| sume hreowlice acwealde | (2) | |

| Sr x x S x | ||

| sume hi man blende | (3) | |

| x x S S x | ||

| 10 | sume hættode | (5) |

| x S x xx S x | ||

| gedon on þison earde | (1) | |

| x x S S x | ||

| and her frið namon | (5) | |

| x x S x Sr | ||

| to ðan leofan gode | (4) | |

| S x x S x | ||

| bliðe mid Criste | (3) | |

| x S x x x S x | ||

| 15 | swa earmlice acwealde. | (1)5 |

The metrical system evident in Alfred is very similar to that in the Brut. Expansion of exactly one dip has become obligatory. The desuetude of the four-position principle, coupled with the reinterpretation of verses with formerly omissible prefixes in anacrusis (11b), has caused the Old English pattern Sx(x …)Sx (Sievers Type A) to acquire an optional third dip, either short with long medial dip (15b) or long with short medial dip (8b). Unlike the later Chastity, Alfred lacks the conservative Old English pattern SxSx (Sievers Type A) in the b-verse. Taken together, Chastity and Alfred furnish evidence of the synchronic diversity of metrical styles. Fifteen late Old English poems omitted from ASPR, including Chastity, are scanned in Appendix A. Each of these poems exhibits a dynamic mixture of more conservative and more innovative metrical features.

The formal trajectory running from the Beowulf meter to the Brut meter belies the perception of decline and decay after 950. All of the “defective verses” that R. D. Fulk identifies in Durham (1104–1109) are metrical when viewed from the diachronic perspective developed in this chapter, e.g.:

| S S x S x | ||

| 4a | ea yðum stronge | (three lifts) |

| S x S Sr x | ||

| 7b | wilda deor monige | (three lifts) |

| x x x x Sx S | ||

| 9a | Is in ðere byri eac | (4) |

| x x x S x p S x | ||

| 20a | ðær monia wundrum gewurðað.6 | (2) |

The “anomalous” anacrusis that Fulk notes in the Battle of Maldon (c. 991) and the “[e]xtraordinary anacrusis” he discerns in Durham are also characteristic of the emergent system, e.g.:

| x Sr x x S x | ||

| Maldon 32b | mid gafole forgyldon | (1) |

| x S x x S x | ||

| Maldon 66b | to lang hit him þuhte. | (1) |

| x S x x S x | ||

| Durham 5b | on floda gemonge.7 | (1) |

Occasional lack of metrical resolution of short, stressed syllables (as in Durham 9a by- in byri ‘town’) is one predictable result of the destabilization of resolution and the four-position principle. The acceptability of Type 2 (Durham 20a) is another.

The metrical developments surveyed thus far mark the disintegration of a set of interdependent structures typified by the Beowulf meter: the four-position principle, metrical resolution, the prefix license, and a morphological basis for metrical stress. Yet the same metrical developments also herald the incipient normative force of a new set of interdependent structures typified by the Brut meter: exactly two lifts in the b-verse, exactly one long dip in the b-verse, decreasing symmetry of a-verse and b-verse patterns (Ch. 3), and an accentual basis for metrical stress. The second point is the crucial one missed by all commentators before Yakovlev. Hence the standard judgment that late Old English and Early Middle English alliterative meter is ‘irregular.’ We are now equipped to say that the net change in regularity from Old English to late Old English to Early Middle English alliterative meter was effectively zero: to the extent that one synchronically coherent configuration of metrical norms began to be effaced, a new configuration began to take shape. The meter of Maldon and Durham is only “defective,” “extraordinary,” or “anomalous” from the perspective of a typologically earlier moment in verse history.

The formal differences between undated and late Old English poetry reflect ongoing metrical evolution. More precisely, the observable evolution of the alliterative meter after 950 implies the unobservable evolution of the alliterative meter before 950. It is only the organization of Old English metrics around Beowulf at one end and the Norman Conquest of England (1066) at the other that creates a monolithic ‘classical’ line in the first place. The long metrical evolution narrated in this book offers a counterweight to the prioritization of the Beowulf meter in Old English metrics. Like the Beowulf poet, late Old English poets practiced metrical styles in use at the time. And like the Beowulf poet, they were successful. In the late tenth and eleventh centuries, more innovative metrical styles included more long dips, less metrical resolution, and innovative metrical patterns, not because poets were losing touch with a static tradition, but because they were engaged in a dynamic one.

To summarize the arguments of this section thus far: an improvement in understanding of the Beowulf meter and the Brut meter ensures an improvement in understanding of late Old English meter and alliterative verse history from Old to Early Middle English. We can go further. These four schemes – the Beowulf meter, late Old English meter, the Brut meter, and the evolutionary arc that connects them – are best conceptualized as four expressions of the same historical formation, the alliterative tradition. Each of the four schemes gains its fullest historical significance when we are able to observe the way in which it interlocks all three of the others. Correspondingly, in much prior scholarship, isolated and synchronic focus on the Beowulf meter, the dim view of late Old English meter, the perception of irregularity in the Brut meter, and the narrative of metrical death and decline after 950 are four facets of the same misapprehension about a poetic tradition. Yakovlev’s dynamic theory of Old English and Early Middle English alliterative meter facilitates a new formalization of late Old English meter, presented in this chapter and in Appendix A; this formalization, in turn, confirms Yakovlev’s reconstruction and supplies a deeper and broader evidentiary basis for it.

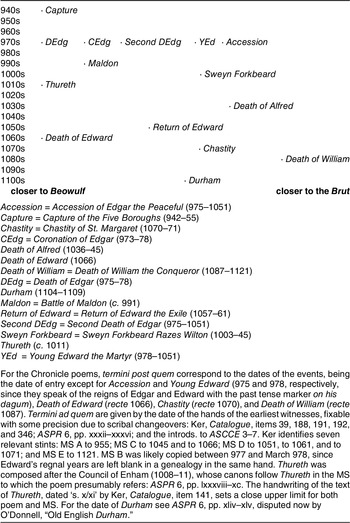

The survival of a number of datably late Old English poems enables us to create new and powerful evidence of metrical evolution and synchronic diversity between 950 and 1100. Figure 1 compares fifteen post-950 poems that are closely datable on non-metrical grounds. Terminus post quem (y-axis) is graphed against six purely metrical features that were unmetrical or rare before 950 but gradually became metrical or common after 950 (x-axis).

The six innovative features are, in descending order of weight: (1) more than 90 percent of b-verses with long dip; (2) Type 2 in the b-verse; (3) Type 1 and/or xSxSx in the b-verse; (4) a-verses with non-b-verse patterns; (5) three-lift b-verses with more than four metrical positions; and (6) complete avoidance of metrical resolution and/or lack of resolution of short, stressed syllables as in Durham 9a byri. In the next section, I contend that the shape of alliterative verse history before 950 remains unknowable in the absence of closely datable poems. Conversely, the date of Beowulf and other long poems remains uncertain without a clearer understanding of developments and trends in alliterative composition before 950. Figure 1 represents the history of alliterative verse as instantiated in several closely datable poems over 150 years. It is against this representation that hypotheses about earlier alliterative verse history should be measured.

Verse History and Language History

Old English metrists have devised a variety of comparative tests for Old English poems, most of which suggest that Beowulf is especially conservative.8 Yet inasmuch as so-called classical Old English meter has been extrapolated from Beowulf to begin with, comparative testing risks exaggerating the poem’s conservatism or typological primacy. Some tests propose to avoid circularity by correlating metrical history with language history. Such efforts are equivocal, however, for at least three reasons. First, in some cases linguists reconstruct early sound changes from the meter of putatively early poems like Beowulf – more circulus in probando. Second, in proposing to test a ‘text,’ ostensibly composed at one time by one poet, metrists must rely on historically inappropriate conceptions of authorship and textual transmission. When multiple copies of a single poem survive, it is evident that scribes often felt free to revise their exemplars, not in violation of metrical principles, but in accordance with them. Different degrees of scribal interventionism could skew evident linguistic-metrical differences between received texts. Third, as I will argue, metrists have been overly optimistic in assuming that metrically significant linguistic form mirrors contemporary linguistic form except in poetic formulas or identifiable instances of conscious archaizing. On the contrary, the linguistic forms encoded by alliterative meter were pervasively conservative. Phantom syllables, absent from contemporary speech but present in the meter, persisted well beyond ossified formulas or synchronically recoverable linguistic forms. In order to emphasize the independence of verse history from language history, I refer to metrically significant linguistic form as ‘metrical phonology.’

That alliterative meter encodes conservative linguistic forms has long been recognized. For example, metrical resolution recapitulates equivalences that are hypothesized to have obtained in prehistoric Old English, when quantity played a larger role in linguistic phonology. Yet resolution remained a regular feature of alliterative meter as late as c. 1200 (in Lawman’s Brut). Recent work in Middle English metrics finds twelfth- and thirteenth-century final -e alive and well in fourteenth-, fifteenth-, and even sixteenth-century alliterative meter (Chs. 4 and 6). In Beowulf one encounters uncontracted forms of words that had lost intervocalic -h- as in gan and seon (‘non-contraction’), lack of vowel parasiting in historically monosyllabic words like morðor and tacen (‘non-parasiting’), compensatory lengthening of vowels following loss of h without subsequent analogical shortening in inflected forms of words like feorh and mearh, a distinction between historically short and historically long unstressed syllables for the purposes of metrical resolution (‘Kaluza’s law’), an ‘elliptical’ dual (2002b uncer Grendles), i-stem genitive plurals in -ia, uninflected infinitives after to, and weak adjectives without determiners. Beowulf also has contracted forms, vowel parasiting, analogical shortening of vowels in inflected forms of words like feorh, i-stem genitive plurals in -a, inflected infinitives after to, and weak adjectives with determiners, establishing that the composition of the poem postdates these linguistic developments.9

Most of these linguistically conservative metrical features appear, though less frequently, in datably late poetry. The Battle of Maldon, for example, has three possible instances of non-parasiting (130b wæpen, 202b ealdor, and 282a broðor, the last two unetymological), one instance of compensatory lengthening (239b meare), and complete adherence to Kaluza’s law (but only three relevant verses: 61a, 262a, and 322a). Finally, in Death of Edgar 11 (975–78), Maldon 256, and Death of Edward 12 (1066), velar and palatal c- alliterate together, whereas the two phonemes had diverged in the Old English language by the ninth century at the latest.10 Clearly, their co-alliteration in some poems was a poetic convention, not a reflection of linguistic reality. Co-alliteration of velar and palatal c- is therefore irrelevant to dating, unless the desuetude of the poetic convention itself could be precisely dated – wholly a matter for metrics in that case, not linguistics. And so on for each metrical feature that encodes older linguistic forms.

Thus the effect of linguistic change on meter is always mediated by historical processes within the metrical system. This claim is more general than the usual objection that poets could have had antiquarian sentiments or special linguistic knowledge. Archaizing is only one of many rhetorical strategies that poets might effect through available metrical techniques; and poets need not have understood, e.g., the linguistic phenomenon of contraction in order to understand that don, gan, hean, etc., could notionally occupy two metrical positions. Sometimes poets can be caught getting etymology wrong, as in Beowulf 2894a morgenlongne dæg, with monosyllabic morgen-, a word that was historically disyllabic.11 At other times, a poet’s linguistic belatedness is concealed in poetic convention, as when the Maldon poet versified in accordance with Kaluza’s law, which corresponds to a phonological opposition that had vanished from the spoken language centuries prior. The point to make is not only that poets’ practice was far more sophisticated than contemporary understandings of that practice could have been, but also that this state of affairs obtained both before and after linguistic change. So for example the mental processes that encode don as a disyllable in Old English meter were as abstract and notional before as after the contraction of don in the Old English language. The precise means by which metrical competence passed from generation to generation have only just begun to attract the attention of metrists and literary historians, but the effects of metrical hysteresis, or what might be called the stickiness of meter, are everywhere apparent.

The methodological problem with linguistic-metrical testing lies in what I have called a category mistake: treating metrical evolution as though it were a type of linguistic evolution. Metaphors drawn from historical linguistics have been so thoroughly internalized in Old English metrics that they have ceased to be perceived as metaphors. Metrists speak of the ‘rule’ of the coda, the ‘conditioning’ of Kaluza’s ‘law,’ etc., purporting to have described linguistic regularities affected directly by linguistic change. So Fulk states that “[Old English] poets attempted to be as conservative as possible” and that “Old English verse is more like everyday speech” than like later English poetry.12 Both programmatic statements illustrate the reduction of verse history to language history, the neutralization of the momentum of a poetic tradition, queried in the present chapter and throughout this book.

In a purely metrical perspective, one might ask why features like non-parasiting should be chronological criteria to begin with. Such features may have served as stylistic ornamentation, used more heavily by some poets than by others. One need not lapse into “an essentially post-Romantic view of the poet as Genius” in order to believe that Old English poets had an intuitive sense of poetic style, however attenuated by traditionality.13 For example, while Beowulf has a more extensively conservative metrical phonology than many other poems, this is true both of etymologically justified non-parasiting as in 2742a morðorbealo maga and of faux or unetymological non-parasiting as in morgenlongne dæg. Twelve possible instances of faux non-parasiting occur in Beowulf, as compared with eight possible instances in most of the rest of the corpus combined.14 The proper conclusion is not that Beowulf is earlier. Any poet familiar with non-parasiting could have drawn the etymologically false analogy morgen : morgne :: tacen : tacne, and some did. Rather, the proper conclusion is that our poet aimed for an elevated metrical style. Whether metrical tradition had preserved for him etymological or unetymological linguistic values seems to have been of no concern whatsoever to the Beowulf poet. Style is the obvious explanation for the concentration of verses like morgenlongne dæg, and it remains a plausible explanation for all the other metrical features more common in Beowulf than elsewhere. For the existence of non-parasiting in alliterative verse, historical explanations must be sought; but for the treatment of non-parasiting in any given poetic text, stylistic explanations remain compelling.

The difficulties inherent in linguistic-metrical approaches to poetic chronology have encouraged a peculiar sort of wordplay, whereby ‘archaic’ means ‘old’ or ‘conservative’ as needed. Klaeber’s Beowulf contains over sixty references to “archaic” features and “archaisms.” When the editors speak of “[t]he linguistic changes that the poem’s archaic features would seem to precede,” it is unclear whether the features are old or conservative, or whether they only “would seem to,” or really do, belong to an earlier era. When the editors offer evidence that “the poem’s language is archaic because the work was composed early,” “archaic” must mean ‘old.’ Yet the concession that “O[ld]E[nglish] poetic language is archaic by nature” requires “archaic” to mean ‘conservative.’

Equivocation is the predictable result of an approach that fails to establish a necessary relationship between language history and verse history. The Beowulf poet’s fidelity to Kaluza’s law is held to indicate that “the distinction between the relevant long and short final vowels had not yet been eliminated when Beowulf was composed, or at least,” the editors quickly add, “had only very recently been eliminated (as the poet’s strict conformity to the law would seem to suggest).”15 If conformity to Kaluza’s law can only “seem to suggest” a date “recently” after c. 725, then a fortiori it cannot establish a date before c. 725. How “recently” is “recently” is a question that linguistics by itself cannot answer, for all the reasons given above. Recall that metrical resolution, which recapitulates prehistoric Old English phonology, survived into the thirteenth century. Or again, twelfth- and thirteenth-century linguistic -e’s are used correctly and extensively in fourteenth-, fifteenth-, and even sixteenth-century alliterative meter (Chs. 4 and 6). Datably post-950 Old English poems exhibit the phenomena described by Kaluza’s law less frequently than Beowulf, but no less regularly. To date a metrical feature by dating a linguistic feature that it encodes, or once encoded, is to mistake one kind of historical form for another.

In my view, a more methodologically sound approach would be to develop purely metrical tests based on changes in the meter itself, as in Figure 1. Because there are good empirical and theoretical reasons to connect them with metrical evolution, the six criteria used in Figure 1 directly measure formal conservatism in a way that linguistic-metrical criteria would not. If the fifteen poems in Figure 1 show considerable synchronic variation in even these most structurally significant features, then, a fortiori, incidental features like non-parasiting will not provide the smooth, century-by-century progression that metrists seek. Instead of stipulating a constant and universal rate of metrical change a priori, Figure 1 maps the metrical conservatism of individual poems against time.

As is to be expected, Figure 1 shows a clear direction of development from the earlier, Beowulf-like poems to the later, Brut-like ones. Nevertheless, some poems diverge considerably from the metrical mainstream. What may be one of the oldest, the Accession of Edgar (975–1051), is among the most metrically innovative of the group, while one of the youngest, Death of Edward, is the most metrically conservative of the group (along with the earlier Capture of the Five Boroughs, 942–55; Death of Edgar; and Thureth, c. 1011).

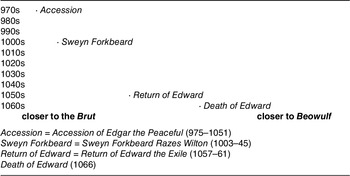

The variation evident in Figure 1 argues for a wide range of metrical styles in use at any one time. If Beowulf was as conservative as the Death of Edward relative to its own verse-historical moment, then it could have been composed long after its style of meter occupied the mainstream. Figure 1 shows that alliterative meter evolved in broadly identifiable ways, but it does not hold out much hope for dating any given text on a metrical basis. Were it possible to create a graph like Figure 1 for the period 700–950, in and of itself this would not date Beowulf, but it would at least fix a sense of scale and directionality to earlier metrical developments. As it is, none of the six innovative features represented in Figure 1 can distinguish Beowulf from Capture of the Five Boroughs, Death of Edgar, Thureth, or even as late a poem as Death of Edward. Figure 1 demonstrates the tenuousness of modern judgments about alliterative verse history. Had only Accession, Sweyn Forkbeard Razes Wilton (1003–45), Return of Edward the Exile (1057–61), and Death of Edward (seventy-five lines in all) happened to survive, scholars might have concluded on a metrical basis that the Brut predated Beowulf (Fig. 2)!

| 970s | ∙ Accession |

| 980s | |

| 990s | |

| 1000s | ∙ Sweyn Forkbeard |

| 1010s | |

| 1020s | |

| 1030s | |

| 1040s | |

| 1050s | ∙ Return of Edward |

| 1060s | ∙ Death of Edward |

| closer to the Brut | closer to Beowulf |

| Accession = Accession of Edgar the Peaceful (975–1051) | |

| Sweyn Forkbeard = Sweyn Forkbeard Razes Wilton (1003–45) | |

| Return of Edward = Return of Edward the Exile (1057–61) | |

| Death of Edward (1066) | |

Figure 2. Select Datably Late Old English Poems in (Reverse) Alliterative Verse History

If this seems like an idle thought experiment, consider that there exists far less uncontroverted evidence for alliterative meter before 850 (twenty-one lines in all).16 The problem with metrical testing, then, is not only that Beowulf might be conservative vis-à-vis the metrical mainstream, but also that the metrical mainstream itself cannot be reconstructed in any usable detail for the decades before 950.

If the dates of Accession and Death of Edward could not be fixed on internal evidence, metrical tests would place them the wrong way round in literary history by a century or more. This should be considered a failure of a most fundamental kind, because it is symptomatic of a reductive conception of verse history. The proposition that metrically more conservative poems are invariably and proportionally earlier than metrically more innovative poems is false for the poems in Figure 1. It is also false for later alliterative poems. For example, recent studies find that Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (late fourteenth century) has an extensively conservative metrical phonology, which counts nearly all historically justified final -e’s, while Piers Plowman (c. 1370–90) appears to have a moderately conservative metrical phonology, which sometimes discounts some historically justified -e’s. Comparison to post-950 alliterative poetry implies a far more complex verse-historical situation before 950 than proponents of metrical tests for chronology had hoped.

The charts drawn up by Geoffrey Russom, in which Old English poems rate ‘bad,’ ‘so-so,’ ‘good,’ or ‘best,’ and ‘early,’ ‘middle,’ or ‘late,’ represent one of the more nuanced attempts to establish a poetic chronology on metrical grounds. Russom starts from a summary of “expert judgments” about the date and literary quality of each poem, based on the proportion of “anomalous verses” or “metrical faults” in each.17 He then sifts through dating criteria in search of those that uphold the “expert judgments” within the context of his word-foot theory of Old English meter. Poems with few “metrical faults” are judged ‘best’ and ‘early’ by the experts, and the best dating criteria are those that reinforce this judgment. By design, Russom ignores criteria that would point in other directions, either to conservative ‘late’ poems, e.g., Death of Edward, or to “anomalous verses” in ‘best’ poems, e.g., innovative five-position patterns in Beowulf. “Diachronic studies of meter,” Russom explains, “begin with the hypothesis that language change makes it increasingly difficult to compose in a traditional form.” Yet the word-foot theory abstracts the “traditional form” of Old English meter precisely by equating linguistic and metrical units. The ostensible correspondence between language history and verse history then acts as a fundamental principle of analysis as well as a historical zero-point. While Russom usefully adopts a diachronic perspective, reference to “anomalous verses” and “metrical faults” still implies a static metrical system gradually effaced by linguistic change.

In a purely metrical perspective, it is not obvious why Russom’s chosen criteria should represent chronological change to the exclusion of generic, stylistic, or diatopic variation. Even if Russom’s criteria are chronologically significant, a ‘bad’-to-‘best’ scale seems insufficiently fine-grained to capture the kind of fluid synchronic variation evident in Figure 1. Indeed, literary quality may not be the most important synchronic variable. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Piers Plowman are both excellent compositions, and both date from the late fourteenth century, but their metrical phonologies are dissimilar. Russom stipulates that “all other things being equal, the earlier of two poems should exhibit the stricter versecraft.”18 This may be a generally valid deduction, but it is unclear how one might determine whether “all other things” are “equal” in any given comparison. The evolution of a dynamic metrical tradition is not likely to be reducible to a chart like Russom’s under the best of circumstances. Figure 1 shows that, on average, innovative features occur more frequently in later poems. That much is by definition: I identified metrical features as ‘innovative’ precisely by observing how they change over time across a corpus of independently datable poetry. Yet Figure 1 also discourages the expectation that each individual poem will represent the mainstream.

A subsidiary problem faced by any comparative approach to poetic chronology is the problem of scale. It is strictly speaking impossible to derive an absolute chronology from a comparison of undated poems. Even if “anomalous verses” and lateness were held to correlate absolutely, at best Russom’s argument would deliver a relative chronology. Beowulf and Exodus, labeled ‘early’ by Russom, could in that case be products of the 850s; Andreas and the Cynewulf corpus, labeled ‘middle,’ could hail from the 910s. The chronological spread of Russom’s ‘early,’ ‘middle,’ and ‘late’ is not an effect of his own argumentation. As he is careful to note, it is adopted from a summary of previous scholarly consensus assembled (and challenged) by Cable in 1981.19 The architects of the previous consensus presupposed that the extant corpus covered the Old English period more or less democratically and that metrical development plodded along at a constant pace for four centuries. Neither assumption is supported by comparison with later and more firmly datable alliterative verse. The majority of extant post-1300 alliterative poems fit in a slender 75-year window, 1350–1425. And the a-verse changed more rapidly between 1250 and 1350 than previously or subsequently: a-verse/b-verse symmetry dropped from c. 95% to 65% between 950 and 1250, but it dropped from c. 65% to 5% between 1250 and 1350.

One final consideration requires a theoretical excursus. It has been urged that, if a very early date for Beowulf cannot be proven, it can be rendered more probable than any alternative. The quibble on Latin probare conceals a misapprehension of the scientific method. In experimentation, a conclusion is valid only when extraneous variables have been ruled out (‘controlled’). Otherwise, the results tend to represent a melange of factors in unknown proportion (‘confounded’). Yet the fragmentary nature of the Old English poetic corpus makes it quite difficult to control for non-chronological variables.

Take conservatism, for example. If Beowulf is metrically conservative, it will test earlier than it is. This is so, regardless of the quantity or variety of recognizably conservative features it contains, since a density of conservative features is exactly what would be expected in a conservative poem. To control for conservatism, one would have to measure Beowulf against comparably conservative poems. However, the metrical conservatism of undated poems cannot be ascertained. Some metrical features, e.g., non-parasiting, might reasonably be identified as conservative in advance of speculation about dating. Yet the degree of their conservatism in a given poem depends on dating: non-parasiting in a tenth-century poem is a more conservative feature than non-parasiting in an eighth-century poem. Moreover, there may occur other, subtler conservative features that do not appear as such to metrical analysis until a date has been determined for the poem in question – the more so if, as I have recommended, the metrical features under discussion are purely metrical, like the four-position principle, rather than linguistic-metrical, like non-parasiting.

Other potential confounding factors are genre, geographical origins, and scribal revision. To extrapolate from metrical phonology to poetic chronology, metrists must proceed as though non-chronological factors had little or no effect on metrical practice. This is the meaning of Russom’s provisional “all other things being equal.” No sooner is the provision made, however, than pre-Conquest England becomes a colorless world, where perfectly average poets plug away at perfectly average poems ad infinitum. Figure 1 contradicts this portrait. Whether style, genre, geography, or (probably) some combination of these factors, it is plain that something other than the passage of time caused considerable variation in the handling of meter.

Nor do regularities in the distribution of conservative features across the corpus reveal that synchronic variables had a negligible effect.20 Rather, it may be the synchronic variables that caused the regularities. Distribution of metrical features along stylistic, generic, or geographical lines, or in accordance with the tastes of a poetic community or a program of metrical revision by editor-scribes, is not a remote possibility. It is the predictable (and after 950 observable) result of literary fashions, genre conventions, cultural formations, and textual mouvance. There is every indication that the extant corpus is not drawn democratically from all regions and all centuries, but that it reflects the tastes and resources of those few who compiled it, c. 950–1025. For example, one of the few securely identifiable groups of Old English poems – the Cynewulf corpus – is not scattered throughout the manuscript record but clustered in two codices. Or again, ninety-six of the ninety-seven texts of Old English riddles are contained in a single codex. One of the longest Old English poetic compositions, the Meters of Boethius, is a revision of the corresponding portions of the Old English prose Boethius and thus may not be metrically comparable to poems composed from scratch. The extant poetic corpus can be expected to overrepresent certain literary fashions, compositional procedures, or scribal-editorial programs of whose very existence we remain ignorant.

More particularly, datable poems are almost always datable because they refer to proximal historical events. Inasmuch as there exist no datable long Old English poems set in the distant past, metrical testing cannot control for genre. (On length and historical setting as genre criteria, see the next chapter.) The datably late poems may overrepresent a less formal metrical style felt to be appropriate to contemporary events or falling within the competence of less talented chronicler-poets. Statisticians refer to such phenomena as ‘sampling bias.’ The potential for sampling bias associated with a tiny and mostly undated corpus constitutes yet another factor whose effect is unknowable, and for which, therefore, metrists have not even the theoretical ability to control. Notwithstanding Fulk’s insistence that “scientists must decide which is the most likely hypothesis,” the scientific method does not require practitioners to draw conclusions when all hypotheses are very tenuous.21 The term reserved by the scientific community for complex effects without isolable causes is ‘not well understood.’

The few surviving datably early Old English poems differ in material context from the bulk of Old English verse. Their value as anchor-texts for literary history is therefore limited. Fulk interprets datably early poems found in late manuscripts as evidence that some of the undated poems must be early.22 Yet Cædmon’s Hymn (late seventh/early eighth centuries), A Proverb from Winfrid’s Time (eighth century), and Bede’s Death Song (eighth/ninth centuries) are all incidental to Latin prose works, which proliferated for reasons quite unrelated to Old English verse.23 (The same material conditions account for the survival of dozens of copies of a few Middle English alliterative poems. I discuss one such embedded snippet in Ch. 5.) The Franks Casket inscription (eighth century), recorded in runes on a whalebone box, is even less materially analogous to anthologized manuscript texts like that of Beowulf.

The synchronic variety of poetic styles and the uneven survival of evidence for poetic communities come together in a recent book-length study by Emily Thornbury. By combining Old English and Anglo-Latin evidence, Thornbury rebuts the presumption that ‘poet’ and ‘poem’ were privileged, transcendental categories whose meanings changed little over time and across space. Instead, she posits contemporaneous “poetic sub-dialects” corresponding to various communities, real or imagined.24 Crucially, Thornbury’s “sub-dialects,” while modeled on linguistic dialects, refer to interpretive rather than linguistic communities. Most notably, Thornbury discerns the contours of a ‘Southern mode’ of late ninth- and tenth-century Old English poetry, marked by a modernized lexicon, Latinate style, and southerly provenance. Metrical differences between Beowulf and poems of the Southern mode, such as the Meters of Boethius and the Paris Psalter, serve as important points of comparison in many dating arguments. Yet these metrical differences may primarily register the fact that Beowulf is not in the Southern mode. It belongs to some other poetic sub-dialect, as yet unidentified, unplaced, and undated. Thornbury does not address the contentions of metrists, but the implications for verse history are there to be drawn out. She concludes her discussion of the Southern mode with a pointed caveat: “Accidents of preservation have made the tenth and eleventh centuries better known to us than earlier ones: but there is no reason to believe that late Anglo-Saxon England was alone in having multiple poetic modes simultaneously available.”25 By checking hypotheses about pre-950 alliterative verse history against Figure 1, I mean to raise the same caveat from a metrical perspective. Figure 1 lends empirical support to the intuition that the historical development of metrical systems is always complex.

In sum, metrical testing for chronology is fraught with several kinds of difficulty. It explicitly assumes the reality of controverted theoretical concepts, such as ‘foot,’ and it implicitly assumes the value of unknown quantities, such as the conservatism of Beowulf.26 Most significantly, I have contended that using any preconceived model of pre-950 verse history in order to discover the date of Beowulf amounts to ignotum per ignotius. Tethering verse history to language history begs the question, for the relationship between metrical form and linguistic form is mediated by structures and processes within verse history. Research at the intersection of metrics and linguistics has achieved a succession of theoretical and empirical accomplishments in Old English studies, especially in recent decades. Metrical features such as the prefix license and resolution are clarified and historicized with the insight that they recapitulate familiar linguistic structures. Interdisciplinary research in this field, however, has almost always proceeded by stipulating a priori the relationship between what I characterize as two independent historical formations, verse history and language history. In my view, judgments about the historically mediated interactions of these two formations should be informed by, but must never be built into, procedures of metrical analysis.

Beowulf and the Unknown Shape of Old English Literary History

The uncanny power of Beowulf lies in its attentiveness to its own multivalent past. The specially ambiguous adverb/conjunction syððan ‘later; ever since’ crops up at key moments to connect story to backstory, as in the introduction of Scyld Scefing (quoted from Klaeber’s Beowulf, ed. Fulk, Bjork, and Niles; translation mine):

The pivot from past to origins is characteristic. In Beowulf, events never just happen. There is always baggage. The poet uses syððan to point up epochal events – Sigemund’s dragon-slaying (886a), the Flood (1689b), the death of Ongentheow (2996b) – that, like Woodstock or the Battle of Gettysburg, evoke foundational eras.27 Even the future has depth, as in the long feud foretold by the Geatish messenger (2911a “orleghwile” “period of war”). The poet takes pains to convey the passing of time between each of Beowulf’s feats (1257b “lange þrage” “for a long time” and 2200b “ufaran dogrum” “in later days”), suggesting triple peaks of heroism protruding from obscurer lowlands. The poet was an expert in the Old English equivalent of montages and flashbacks. At times the building up of temporal perspective becomes intensely idiomatic, and syððan means something like ‘when’:

“Where Hygelac was killed, when the Geatish king … died” sounds redundant to modern ears, but the two dependent clauses achieve different poetic effects. First the poet recounts the battle in Frisia, then the frame of reference opens outward to include the stretch of years between Hygelac’s death and Beowulf’s dragon-fight. The poet serves up the raid on Frisia in short view and long view, making clear, without condescending to explain it, the connection between digression and action.

Given this recursive attention to origins within the poem, every aspect of the poem’s style should be suspected of contributing to its historicist aesthetic. Words in Beowulf singled out by modern scholars as ‘archaic’ are likely to refer to some burnished thing, lost to time in the poet’s own day. One recent argument for a very early Beowulf is Dennis Cronan’s argument from lexis.28 Cronan’s list of simplexes occurring uniquely in Beowulf and one other poem reads like a list of fancy words for distant worlds. In the distant past, a king is not only a cyning, but a þengel (1507a) and an eodor (428a, 663a, and 1044a); a ship is not only a scip, but a fær (33b); a sword is not only a sword, but a heoru (1285a). These words occur a handful of times, as if someone had tried to spice Beowulf with as many exotic flavors as possible. The simplexes found only in Beowulf and a group of poems suspected early by Cronan (Daniel, Exodus, Genesis A, Maxims I, and Widsith) are certainly striking evidence of overlapping wordhoards. As against a generic explanation for the co-occurrences, Cronan objects that “[t]he poems in question belong to a range of genres, including heroic epic, gnomic verse, catalogue verse and biblical history.” Yet these are modern categories denoting kinds of subject matter, not medieval categories denoting kinds of poem. The next chapter uses formal evidence to extrapolate a more organic typology of Old English poems, in which, incidentally, Beowulf is grouped with Daniel, Exodus, Genesis A, and Widsith. Cronan also doubts a stylistic explanation for the shared words. “It is possible that these poems belong to a local tradition or school of poetry,” he reasons. “But we know nothing of such schools – not even if they existed – and explaining this conservative diction through an unknown is poor methodology.”29 I have argued that Figure 1 and other evidence supports the presumption of “poetic sub-dialects” before 950. The diversity and robustness of pre-950 verse history is only “an unknown” in the evidential sense that it cannot be directly observed, not in the ontological sense that it may not have obtained. Whether poems with similar wordhoards constitute dedicated “schools” or merely register the pressure of other historical formations (audience, genre, geography, contact with Old Norse literature, etc.) must remain an open question.

The caution that one should avoid explaining phenomena through an unknown quantity applies no less to chronological arguments than to other kinds. Without assuming beforehand the poetic chronology one means to discover, it is impossible to measure the lifespan of any given lexical item. Very few of the simplexes discussed by Cronan appear in prose or glosses of any period, suggesting the pervasive conservatism of the alliterative poetic lexicon throughout its history. Indeed, Cronan begins by defining ‘poetic simplex’ as “any simple word … whose occurrence is either completely restricted to poetry, or whose use in prose or glosses seems to be exceptional in some way,” a selection procedure reified by his subsequent argument that “the complete absence of suhtriga from prose of any period coupled with its use in poetry and its preservation in a series of archaic glosses makes it clear that this is a word which became obsolete early in the Anglo-Saxon period.”30 A more obvious explanation for the rarity of suhtriga ‘brother’s son’ is that nephews rarely appear in Old English poetry: the more prosaic synonyms broðorsunu ‘brother’s son,’ broðor bearn ‘brother’s child,’ and nefa ‘nephew’ together occur in only four poems (Beowulf, Genesis A, Riddle 1, and Return of Edward). The two longest of these, Beowulf and Genesis A, also contain forms of suhtriga.

Rare poetic words for more common things, like fær ‘ship,’ may well have flourished more in one century, region, community, genre, or level of formality than another; but rarity by itself cannot serve to distinguish diachronic variation from the many other kinds of variation within poetic tradition. As a feature of style, poetic lexis characterizes the alliterative tradition from Old to Middle English. In 1066 the Death of Edward poet was still rhapsodizing about a wel geþungen ‘well-thriven’ ruler (9a and Beowulf 1927a), oretmægcum ‘champions’ (11b and Beowulf 332a, 363b, and 481b), hagestealde ‘young warriors’ (14b and Beowulf 1889a), and a þeodkyning ‘national king’ (34b and Beowulf 2a, 2144a, 2694b, etc.). On the eve of the Norman Conquest, the old language of the comitatus was still just the right thing for eulogizing kings in conservative poetry. The relationship of Beowulf to newer and older lexical sets will have been no less mediated by the (unknown) contours of its verse-historical moment.

Beowulf has a way of creating its historical context, Tennessee-jar-like. A second recent argument for a very early Beowulf is Leonard Neidorf’s argument from cultural change. Neidorf shows how a tale of the heroic yesteryear would have appealed to an Æthelredian audience, only to argue that the heroes themselves had “fallen out of cultural memory” by 1000. “[A]t a time when the past, including the migration-era past, had acquired newfound urgency and importance,” English audiences set a high price on “unfamiliarity and antiquity.” In the eleventh century, Neidorf explains, “it did not matter if characters were unknown or allusions were befuddling,” so long as the events took place in geardagum ‘in the days of yore’ (1b).31 There is something odd about all this. Surely English audiences did not give up understanding literary allusions on the eve of the second millennium. Stripped of any meaning, the numerous digressions in Beowulf make for hard going. Moreover, from the opening scene of a pagan ship burial through the fight with an ancient fire-breathing dragon, “unfamiliarity and antiquity” are integral to the poetic project of Beowulf and will have contributed to its appeal at any given moment in literary history. The very existence of the Beowulf manuscript, then, problematizes any cultural cataclysm of the kind postulated by Neidorf. In dating Beowulf by reconstructing early literary and cultural history, Neidorf projects cultural change as a totalized and irrevocable boundary separating monolithic historical periods that coincide with monolithic periods of literary production. As against such a schematic historicism, the example of the Death of Edward shows how cultural knowledge is preserved and refracted through the prism of poetic style.

In a series of essays with overlapping arguments, Neidorf also attributes chronological significance to scribal errors of proper names in the Beowulf manuscript. According to Neidorf, “the collective presence of scribal errors of proper names in the Beowulf manuscript indicates that the scribes were largely unaware of the heroic-legendary traditions constituting Beowulf; that these traditions were no longer in widespread circulation by the time the manuscript was copied out … and perhaps well before then.”32 Of thirty-seven errors listed by Neidorf, most are of an assuredly mechanical nature, e.g., MS wereda ‘troops’ at 2186a for presumptive Wedera ‘Weders.’ Some bespeak misprision of meter and syntax without misrecognition of the names, e.g., MS fres cyning ‘Frisian king’ (nominative singular) at 2503b for presumptive Frescyninge (dative singular). Six may not be errors at all.33

Neidorf’s analysis presupposes that scribes would not or could not miscopy names of figures known to them or their contemporaries. Evidence to the contrary is not far to seek. In an important study of Old English scribal habitus, Kenneth Sisam noted multiple scribal errors of biblical names in the Exeter Book and the Junius MS (both late tenth century).34 The text of Genesis A, the poem closest in length to Beowulf, contains two scribal errors of biblical names noted by Sisam (leoht for 1938b Loth and leohtes for 2402b Lothes) and at least eleven others not mentioned by him (186a Eve omitted, sedes for 1133b Sethes, cain for 1155b Cainan, caines for 1160a Cainanes, cham for 1617a Chanan, ne breðer for 1628a Nebroðes, carram for 1747b Carran, siem for 1783a Sicem, 2216a Sarran misdivided sar ran with an erasure, agan for 2252b Agar, and sarran for 2715b Sarra). Scribe A of the Beowulf manuscript or an earlier scribe mishandled the name Cain in both of its occurrences (the first later corrected).35 Yet no one has interpreted these errors as evidence that biblical traditions “were no longer in widespread circulation” by the late tenth century. As might be expected, scribes had difficulty with proper names in general. And textual errors, once committed, tend to persist: if the received text of Beowulf is the end result of several transcriptions, each contributing a negligible number of errors of proper names, this would mitigate the impression that late scribes “were largely unaware of … heroic-legendary traditions.” The equation of textual corruption with cultural change is difficult to justify, because the former occurs routinely without the latter.

If the Beowulf scribes did suffer from a case of “cultural amnesia,” it must have been very selective, for they copied hundreds of other proper names without incident.36 The names copied correctly by the scribes include 17 of the 27 names that appear in Neidorf’s 37 errors: (-)Dene, Finn, Fres-, Grendel, Heardred, Heathobeard, Hrethric, Hygelac, Ohtere, Ongentheow, Scilfing, Scylding, Sigemund, Sweon, Weder, Weohstan, and Wonred(-). It is tendentious to count the errors but discount the successes. Surely the point to make, by the numbers, is that Scribes A and B were exceedingly familiar with the Northern world of Beowulf. Other late scribes, too, successfully transcribed the names of legendary heroes. A few decades earlier, the Exeter Book scribe copied over 200 proper names in the text of Widsith, including names found also in Beowulf, with as few as 3 evident errors.37 The scribe of the unique manuscript of Æthelweard’s Chronicon (copied early eleventh century) managed to spell ‘Ingild,’ ‘Fin,’ ‘Geat,’ ‘Beo,’ ‘Scyld,’ and ‘Scef.’ Beow, Heremod, Scyld, and Scef appear together, with a grand total of one scribal error, in the unique manuscript of Asser’s Vita Alfredi (c. 893, copied c. 1000), in Cotton Tiberius B.v (early eleventh century), twice in the ‘Textus Roffensis’ (1115–24), and in William of Malmesbury’s Gesta regum Anglorum (c. 1142, copied in the twelfth century and later).38 Insofar as transcriptional accuracy corresponds to cultural knowledge, these legendary figures seem to have been well known to literate audiences around the time of the copying of Beowulf and later.

Finally, even if one concludes from such equivocal evidence that “the scribes were largely unaware of the heroic-legendary traditions constituting Beowulf,” this conclusion itself has no necessary chronological implications. Surely it is an oversimplification to equate the cultural knowledge of two individuals with the “cultural memory” of England for two centuries. If the mistranscription of proper names in the text of Beowulf bears witness to a differential in cultural knowledge, it could just as well point to the diversity of ninth-, tenth-, and eleventh-century interpretive communities as to a 300-year cultural chasm separating the poet from the scribes. The impossible word division in MS mere wio ingasmilts at 2921 for presumptive Merewioingas milts ‘the Merovingian’s favor’ sums up the problems with the argument from scribal error. Either the scribe misdivided a name he in fact knew, or he was ignorant of a name that was demonstrably familiar to late authors.39 Scribal error is weak evidence for scribal ignorance; and scribal ignorance is even weaker evidence for a long-standing, universal loss of cultural knowledge.

If no sure signs of “cultural amnesia” can be found in the scribal performance, then perhaps given names might be made to talk. Some years ago Patrick Wormald, reasoning that Beowulf was written for the aristocracy, looked for plutocrats named Wiglaf, Ingeld, etc., and found more in the eighth century than later.40 Neidorf repeatedly represents Wormald’s work as having shown “that many of these names are prevalent in documents prior to 840, but rare or nonexistent afterward.”41 In fact, Wormald excluded non-aristocratic names from his tallies. His goal was not to demonstrate the desuetude of heroic legend among the Anglo-Saxons generally, but to point to a time when the upper classes might have been receptive to a poem like Beowulf. Had Wormald considered landowners to be a potential audience for poems about ancient heroes, he would have found no less than thirty-four relevant names attached to hundreds of historical persons in Domesday Book (1086) (approximate number of individuals, Old English alternatives, and Old Norse and Old High German equivalents in parentheses): Ægelmund/Æthelmund (three; OE Ealhmund), Ælfhere (five–six; ON Álfarr), Ælfwine (dozens; OE Æthelwine, Ealdwine, Ealhwine), Beowulf (one; ON Bjólfr),42 Bil (one; ON Bíldr), Eadwine (hundreds), Finn (three–four; ON Finnr), Folcwald (two), Froda (one; ON Fróði), Garmund (one), Hagena (one; ON Högni), Healfdene (dozens; ON Hálfdan), Hemming (one; ON Hemmingr), Hoc (one or two), Hrothmund (one), Hrothulf (three–five; OHG Radulf, ON Hrólfr), Hun (one; OE Huna, ON Húni), Hungar (two), Ingeld (three; ON Ingjaldr), Offa (three; OE Uffa), Ordlaf (one), Sæferth/Sæfrith (one), Sceaf(a) (one; ON Skeifi), Sigeferth/Sigefrith (one–two; ON Sigfrøðr), Sigemund (three or four; ON Sigmundr), Swerting (one; ON Svertingr), Theodric (ten), Wada (three; OHG Wado), Weland (one), Wiglaf (one), Wudga (one), Wulf (dozens; ON Úlfr), Wulfgar (ten), and Wulfhere (three or four; ON Úlfarr). Eight of these names Wormald listed as “recorded only poetically (i.e. in poetry but not in historical sources)”: Healfdene, Hemming, Hungar, Sæferth, Swerting, Weland, Wudga, and Wulf.43 Ten others appear either once or not at all in the pre-840 historical documents canvassed by Wormald: Ælfhere, Bil(ling), Finn, Folcwald, Froda, Garmund, Hagena, Hrothmund, Ordlaf, and Sceaf(a). Inasmuch as name-giving correlates with knowledge of legend, the eleventh century seems as hospitable to Beowulf as the eighth.

However, as Wormald was careful to emphasize, the connection between name-giving and legends is speculative. A spate of heroic-legendary given names does not necessarily indicate familiarity with legend, just as a decline in the popularity of those names does not necessarily indicate ignorance of legend. People tend to be named after family members, or they are given a name from among the socially acceptable ones. The apparent desuetude of some heroic-legendary given names from the seventh to the tenth centuries may reflect parents’ increasing reliance on a standardized pool of name elements (‘themes’), e.g., Beorht-, Ead-, -wine, -wulf. As name-giving fashions shifted away from naming children after family members (or heroes), exotic names like Ætla and Eadgils would have gradually disappeared as a matter of course. That Wormald found ninety-four men whose names begin with ‘Hyge-’ before 840 and none thereafter means only that ‘Hyge-’ became unfashionable as a first name element (‘prototheme’) after 840. This development almost certainly had nothing to do with the name Hygelac in particular, much less with “cultural amnesia” about Hygelac the legendary king. Names found in legend and composed of less common themes, such as Eadgils and Widsith, are at least as likely to have dropped out of the onomasticon through normal processes of cyclical fashions as through the influence of changing cultural knowledge. Finally, if the Beowulf poet endeavored to recreate a remote time and place, the choice of heroes whose names had already gone out of style as given names could have enhanced the effect. Whether or not one is prepared to believe that an Old English poet could have made this kind of conscious literary choice, it remains the case that poets and parents bestow names for irreducibly different reasons. The argument from onomastics cannot sidestep the vexed question of the Beowulf poet’s rhetorical priorities.

The arguments from cultural change, scribal error, and onomastics all rely on an overdetermined identification of cultural traditions with literary traditions. Thus Neidorf takes as his object of study “the heroic-legendary traditions constituting Beowulf.” In an analogous argument for a very early date of composition for Widsith, he seeks to subordinate the “present Großform” of that poem to its “content.”44 Such perceptions amount to another category mistake. Throughout this book, I argue that meter and poetic style are the only historical materials “constituting” alliterative poems. Poetic form is precisely that historically variable structure through which forms of culture are amplified, focalized, refracted, or even coined in verse. To treat cultural traditions and poetic “content” as interchangeable entities is to ignore the matrix of expectations and conventions that divide the one from the other. To cast aside the “Großform” of a poem, it seems to me, is to cast aside the poem as such.

In his epoch-making 1936 lecture, J. R. R. Tolkien deprecated in the scholarship of his predecessors and contemporaries “the belief that [Beowulf] was something it was not – for example, primitive, pagan, Teutonic, an allegory (political or mythical), or most often, an epic, or … disappointment at the discovery that it was itself and not something that the scholar would have liked better – for example, a heathen heroic lay, a history of Sweden, a manual of Germanic antiquities, or a Nordic Summa Theologica.”45 Tolkien’s impassioned plea for “the understanding of a poem as a poem” has lost none of its relevance for Beowulf scholarship.46 The five methods of dating Beowulf reviewed in this chapter can succeed only to the extent that they reduce verse history to some other historical series, whether language, lexis, culture, textual transmission, or name-giving. Each of the methods finds it necessary to posit a historical moment when poetic tradition was simply continuous with another form of history: a moment when metrical phonology mirrored linguistic phonology; conservative poetic lexis was not yet conservative or poetic; the content of imaginative compositions embodied the “cultural memory” of an entire island; scribal accuracy, scribal knowledge of literary figures, and cultural knowledge of legendary heroes overlapped completely; and the literary circulation of poems coincided with the historical circulation of given names featured in those poems. Each of the methods goes on to measure the antiquity of Beowulf by estimating the distance between this hypothesized moment and the knowable literary-cultural situation of the late tenth century.

My intervention has been to assert the independence of verse history from each of these other kinds of historical reconstruction. Because the lineaments of pre-950 verse history cannot be ascertained, I suggest, the relationship of putatively pre-950 verse to language, lexis, culture, scribal transmission, and name-giving cannot be assessed. Reconstructions of a very early Beowulf will continue to be implausible so long as they continue to reduce poetic meter and poetic techniques to some other kind of better-understood historical material. The observable diversity, diffusion, and conventionality of English literary culture after 950 is not evidence of the decay of a once monolithic, consolidated, and naturalized poetic tradition; rather, it implies the unobservable diversity, diffusion, and conventionality of English literary culture before 950. In this chapter, I have contended that metrical and other arguments for a very early Beowulf are either logically invalid, i.e., proceeding from true premises but failing to arrive at necessary conclusions, or logically unsound, i.e., arriving at necessary conclusions but proceeding from false premises. In either case, the arguments reviewed in this chapter fail to establish an early date for Beowulf because they fail fully to reckon with a poem as a poem and verse history as history.

The conclusions of this chapter, then, are negative. The next chapter builds a preliminary model of Old English poetic genres and poetic communities on what I take to be the best available evidence, the form and style of the poems themselves. I develop a typology of prologues to long Old English poems, with special emphasis on the undated poems. The interpenetration of individual types of prologue across the Old English poetic canon provides further support for the presumption of a robust history of alliterative verse before 950, unsettles modern notions of Old English poetic kinds, and contextualizes the style of Beowulf in a new way.