1. Introduction

In 1894, Jacob Barth proposed that the preformative conjugation in some of the Semitic languages goes back to an inverse correlation between the thematic vowel of the stem and that of the conjugational prefix, yielding the patterns yaqtul, yaqtil and yiqtal. Evidence for such a distribution is well attested in all branches of Central Semitic, yet it remains disputed whether it should be reconstructed for Proto-Semitic as well. The present paper revisits this debate, proposing new evidence that may corroborate such a reconstruction. We make use of data recently recorded from a living Semitic variety, namely the Arabic dialect of Ḥugariyyah in the south of Yemen, where the pattern observed by Barth is still operative. This specific variety not only provides a living demonstration of an extremely archaic feature, but also evidences productive shifts in the distribution of the preformative vowels in the transition from the bare imperfect to the future tense paradigm. By observing these shifts we apply the uniformity principle formulated by the Neogrammarians and propose a comparable development that may have operated in other languages.

Discussions on the reconstruction of proto-languages are speculative by nature. Any hypothesis in this context relies heavily on the methodological principles that are perceived as most suitable for the reconstruction. Our main purpose in the present article is to demonstrate how previous ideas accounting for the historical process, that were inevitably speculative in the absence of factual attestation, can now find evidence in a Semitic variety still spoken today.

The structure of this article is as follows: Section 2 surveys four configurations of the preformative conjugation that are found throughout Semitic languages. This distribution raises the comparative linguistic question of which of the four should be reconstructed for Proto-Semitic. In Section 3, we provide data from the Arabic dialect of Ḥugariyyah and point to the shift in the quality of the preformative vowels in the transition from the bare imperfect to the future tense paradigm. In Section 4, we evaluate the historical relations between the four configurations and propose an analysis, assuming the distribution reconstructed by Barth as a starting point for all other configurations.

2. The four configurations of the preformative conjugation in Semitic

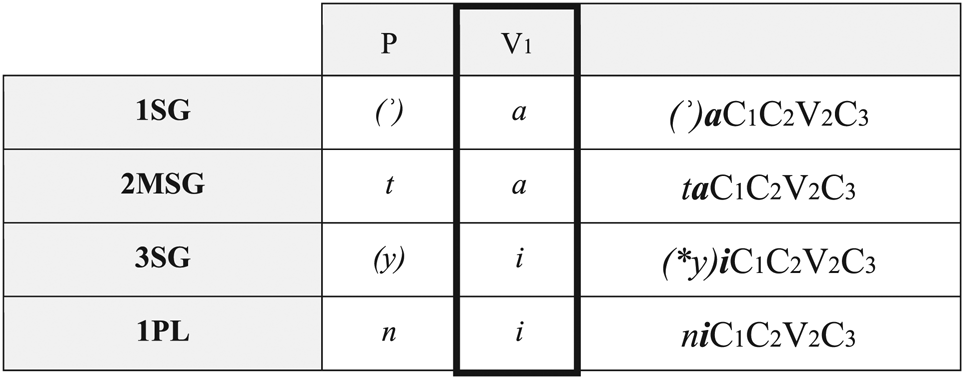

The Semitic preformative conjugation consists of the following phonological components:

• a consonantal prefix that varies according to person (P)

• a preformative vowel (V1)

• a verbal consonantal root (C1C2C3)

• a thematic vowel (V2)

We shall use the following scheme to discuss the arrangement and positioning of these constituents within the paradigms of the various languages and dialects examined:

Scheme 1. The Semitic preformative conjugation

The consonantal root (C1C2C3) and thematic vowel (V2) are, by and large, lexically determined.Footnote 2 Exceptions to this claim include cases in which V2 is phonetically determined, i.e. influenced by the neighbouring root consonants (Brockelmann Reference Brockelmann1908: 546; Driver Reference Driver1936: 43, 64). Predominantly, in many Semitic varieties a laryngeal C2/C3 yields, by default, V2 = a. Several modern Arabic dialects tend to exhibit V2 = u for a back-palatal and/or labial C2/C3, as is the case, e.g. in Muslim Baghdadi (Blanc Reference Blanc1964: 99; Abu-Haidar Reference Abu-Haidar, Edzard and Jong2011), or in North-Yemeni (Shachmon Reference Shachmon2022: 32–3).

The consonantal prefix (P), on the other hand, is grammatically determined, and across the Semitic languages there is much uniformity of the consonants representing the grammatical persons. There are, however, documented cases of changes with respect to P. Among other cases, we mention the use of l/n for 3rd person masculine singular/plural in Late Eastern Aramaic (Nöldeke Reference Theodor1904/2001: 104; Bar-Asher Siegal Reference Bar-Asher Siegal2016: 128–9); n for the 1st person singular in the Western Neo-Aramaic dialect of Maʿlūla (Fassberg Reference Fassberg, Huehnergard and Pal-El2019: 643); n for the 1st person singular in all Maghrebi Arabic dialects (Fischer and Jastrow Reference Fischer and Jastrow1980: 261); and y for the 1st person singular in spoken Modern Hebrew (personal knowledge).

The quality of the preformative vowel (V1) stands at the heart of our discussion, as we observe several options for the behaviour of V1 throughout Semitic languages. In this section, we review four possible configurations (A–D), basing ourselves on the available documented languages. Broadly speaking, the configurations differ with respect to what determines the quality of V1. In the patterning schemes we give below, configurations A and B represent varieties where V1 is part of the grammar, whereas configurations C and D refer to cases where the quality of V1 correlates with the thematic vowel (V2), and as such, is also determined by a lexical constituent.

(A) The invariable V1: either a or i throughout the paradigm

Several Semitic languages exhibit an invariable preformative vowel for all roots (or for a large set of phonologically characterized roots, predominantly the sound verb). This vowel features either a or i in the various languages and dialects.

Scheme 2. The invariable V1

The pattern PiC1C2V2C3 is widespread in different parts of West Semitics. In Hebrew, both classical and modern, for example, we encounter V1 = i as the default in all sound roots (Blau Reference Blau2010: 204), e.g. yilmad “he will study” or yišmor “he will keep”. Similarly, the Syriac (Later Eastern Aramaic) sound verb exhibits V1 = e which is a reflex of Proto Semitic i (Brockelman Reference Brockelmann1908: 65): nedḥal “he will fear”, neqṭol “he will kill”. Both Hebrew and Syriac, however, exhibit the exception of V1 = a with C1-pharyngeals (see further in the discussion of configuration D below).

Classical Arabic, in its standardized form that evolved during the first Islamic centuries, features an invariable PaC1C2V2C3 pattern, e.g. yaftaḥu “he opens”, yaktubu “he writes”, and yanzilu “he descends”. According to the medieval Arab grammarians, invariable a-preformatives characterized the pre-Islamic dialects of the Ḥijāz and its surroundings (Rabin Reference Rabin1951: 61; Bloch Reference Bloch1967: 23).

In Modern Arabic dialects, V1 = i is prevalent mainly outside the Arabian Peninsula (Rosenhouse Reference Rosenhouse, Edzard and Jong2011a),Footnote 3 but also inside it, e.g. in the dialect of Riyadh (Ingham Reference Ingham1994: 194), as well as in Ṣanʿāni and several other Yemeni varieties (Watson Reference Watson, Edzard and Jong2011; Behnstedt Reference Behnstedt2016: map 093). V1 = a is characteristic of many dialects inside the Arabian Peninsula to this very day, among which are Najdi and Eastern Arabian dialects (Ingham Reference Ingham1994: 194); as well as of Nomadic Syro-Mesopotamian dialects, the offshoots of the same Arabian group (Rosenhouse Reference Rosenhouse, Edzard and Jong2011a). In Yemen, V1 = a characterizes the dialects of the Red Sea coastal plain, or Tihāma, and the area known as Šarʿab, north of the city of Taʿizz; examples include yafraḥ “rejoice”, yargum “throw” and yaxrig “go out” (our corpus). V1 = a was also reported for Ḥugariyyah, south of Taʿizz (Behnstedt Reference Behnstedt2016: map 093), although, as we demonstrate below, our findings do not show this.

(B) The variable V1: a and i distributed according to person

Under configuration B we classify cases in Semitic where V1 varies throughout the paradigm and is determined by the person. A prominent demonstration of this configuration is Akkadian: V1 = a in the 1st person singular and all 2nd person, whereas it is i in the 1st person plural and the 3rd person singular (see Scheme 3).Footnote 4

Scheme 3. The variable, person-determined scheme

Yet, in contrast to what is often described in the literature, Akkadian is not the only instance of configuration B in Semitic. In fact, comparable distribution is attested in a few modern Arabic dialects. For example, Nigerian Arabic exhibits taktub “you.msg write” vs. iktub “he writes” (Owens Reference Owens2015: 7). Behnstedt (Reference Behnstedt2016: 223) reports a variation of a~i preformatives in a few localities in South-West Yemen, e.g. taqtilu “you.mpl kill” vs. yiqtilu “they.m kill”. In all these cases, it is evident that the 2nd person, where P=t, constitutes the exception: ta- stands in opposition to yi-,ni- in the rest of the paradigm.

(C) The harmonic distribution: positive correlation between V1 and V2

Several modern varieties of Arabic demonstrate positive correlation between V1 and V2, yielding three harmonic patterns (see Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. The harmonic distribution scheme

Such a system has been reported for several groups in the Northern Sinai Littoral (the Western branch of North-West Arabian); examples include yašṛaḅ “he drinks”, yugʿud “he sits” and yimsik “he grabs” (Palva Reference Palva and Forstner1991: 160–1; de Jong Reference Jong2000: 190).Footnote 5 Comparable patterns are observed in North African dialects, specifically in the Bedouin dialects of Libya and Tunisia (Fischer and Jastrow Reference Fischer and Jastrow1980: 261; Rosenhouse Reference Rosenhouse, Edzard and Jong2011a).Footnote 6 Systems exhibiting configuration C have plausibly emerged as a result of secondary assimilation, as further discussed in Section 4.2 below.

(D) The disharmonic distribution: negative correlation between V1 and V2

Negative correlation has been noticed in several old and modern Semitic varieties, where a low V1 precedes a high V2, and a high V1 precedes a low V2 (see Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. The disharmonic distribution scheme

This disharmonic distribution was noted by Jacob Barth (Reference Barth1894), and evidence for it is attested in the various sub-branches of Central Semitic.Footnote 7 In various languages, especially North-west Semitic, this distribution can be identified only in certain weak-verb paradigms. Consider, for example, the two C1-guttural verbs in Hebrew: yaḥšob “he will reckon” vs. yeḥzaq “he will grow strong”.

The negative correlation may also be traced in Arabic, as was noted by Barth himself (Reference Barth1894: 5). According to the Arab grammarians, while pre-Islamic western dialects exhibited invariable a-imperfects (see configuration A above),Footnote 8 the eastern varieties exhibited both a and i as preformative vowels, with the high V1 preceding a low V2 (Rabin Reference Rabin1951: 61; Bloch Reference Bloch1967: 23). This alternation, known in Arabic as taltala,Footnote 9 is supported by inscriptions of Old Arabic written in Greek letters, as recently shown by Al-Jallad and al-Manaser (Reference Al-Jallad2015: 56; Reference Al-Jallad and Al-Jallad2017: 178; Reference Al-Jallad2020: 100). Vestiges of that older stage are also attested by some qirāʾāt (Qurʾānic readings), exhibiting ni-/ti- prefixes before V2 = a instead of the expected Classical na-/ta- (Rabin Reference Rabin1951: 61; Al-Qabāqibī Reference Al-Qabāqibī2003: 91–2).Footnote 10 Yet, as with other linguistic features that existed in the pre-standardized language, these dialectal variants have been eliminated from the texts in the course of standardization (Fischer Reference Fischer, Edzard and Jong2011), resulting in an invariable V1 = a.

In modern varieties, a “dissimilation pattern”, or “rule of vowel dissimilation”, was reported for the dialect of Sudayr in the central area of Najd (Ingham Reference Ingham1994: 28, 194), and is also “a noticeable feature of speech in most areas of the Gulf” (Holes Reference Holes2010: 156), yielding the patterns yafʿil or yifʿal, occasionally also yafʿul (Johnstone Reference Johnstone1967: 43).Footnote 11 Van Putten has recently (Reference Van Putten, Čéplö and Drobný2020: 84) argued that C1-guttural verbs in Maltese and Tunis Arabic also retain the inverse alternation of the imperfect prefix. We observe that the disharmonic distribution is fully productive in the Yemeni dialect of Ḥugariyyah, as will be discussed in detail in the next section.Footnote 12

Thus, evidence for a disharmonic distribution is convincingly attested in Central Semitic. It remains disputed, however, whether this configuration should be reconstructed for Proto-Semitic as a whole. While some argue that a negative correlation between V1 and V2 indeed reflects the distribution of Proto-Semitic, others adhere to the concept that a configuration of type B is more likely to reflect that hypothetical proto-stage. In the following sections, we present recent data from a modern Arabic dialect, and show that certain phonological changes that occur in it may be viewed as a transitional stage linking configuration B with configuration D.

3. Data from Ḥugariyyah: living evidence for configuration D

The data examined below was gathered in the years 2019–20, as part of the first author's continuous efforts to document the speech of Jewish immigrants from Yemen. For this part of the project, we analysed sample texts from twelve informants (four men and eight women), who hail from Ḥugariyyah, a district South of Taʿizz in the south of Yemen. They all left Ḥugariyyah for Israel around 1950 in the “Operation on the Wings of Eagles”.Footnote 13 They came from six different villages in the area discussed, namely (abbreviation of the informant's name is given in brackets): Banḗ Yūsef (ĠŠ), Ḥarf alHaygāh (WḎ̣), aḏ̣Ḏ̣ammāgī (BY, BA), alGabziyyah (MY, SṢ, RṢ, RzṢ), alGwīrah (YR, ShX, ASh) and Sínwān (ḤA). Interviews with the informants took place in their homes in various localities around Israel, through open-ended conversations. They were encouraged to speak on topics of their choice. Later on, in order to expand our database and evaluate our observations, we added several elicitation sessions with six of the informants. In addition to our own materials we also consulted recorded materials from the archives of Ephrayim Yaakov in Jerusalem, that include, inter alia, interviews conducted in the 1980s with Jewish immigrants from Ḥugariyyah, in a mixture of Hebrew and Arabic.Footnote 14

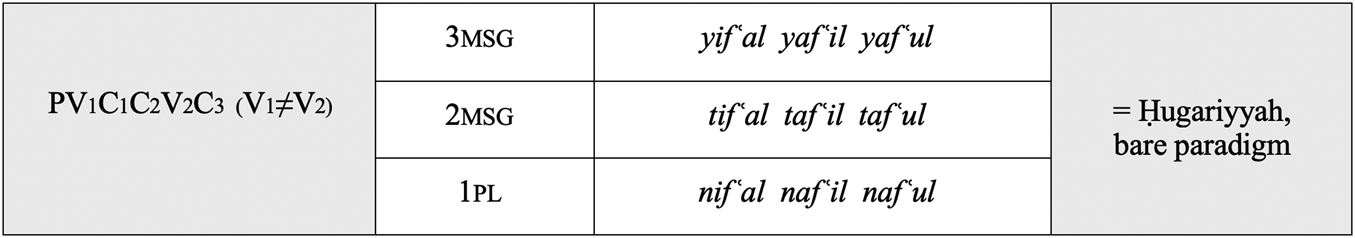

3.1. The distribution of V1 in Ḥugariyyah

As already noted by Diem (Reference Diem1973: 124) and Behnstedt (Reference Behnstedt2016: 223), certain dialects in the area of Ḥugariyyah exhibit both a and i as V1.Footnote 15 Our observations confirm some of these findings, but at the same time complete the existing descriptions and add essential details to them. We observe that all G-stem verbs in Ḥugariyyah exhibit the disharmonic distribution classified above under configuration D: V1 consistently surfaces as i before a low theme vowel, and as a when V2 is high.

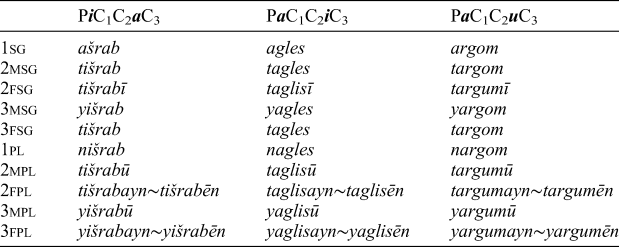

Table 1 contains representative paradigms of the three imperfect patterns in Ḥugariyyah, using the roots š.r.b “to drink” (pattern PiC1C2aC3); g.l.s “to sit” (pattern PaC1C2iC3);Footnote 16 and r.g.m “to throw” (pattern PaC1C2uC3). An exception to the rule of inverse correlation is the 1st person singular, that uniformly exhibits a. Also note that the high vowels i and u are lowered in this variety to e and o respectively in final closed syllables.Footnote 17

Table 1 Inverse correlation in G-stem verbs in Ḥugariyyah

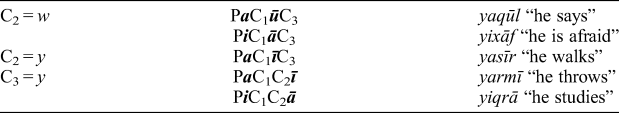

Apart from the sound verb, second- and third-weak roots exhibit comparable patterns. When V2 is either i or u, the preformative vowel surfaces as a. With V2 = a we observe V1 = i, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Inverse correlation in second- and third-weak verbs in Ḥugariyyah

The asymmetric distribution of V1 and V2 is thus maintained in sound verbs as well as in second- and third-weak roots. It may, however, be violated in certain phonetic environments: the occurrence of gutturals and back palatals in the root may, yet does not necessarily, involve a positive a-a correlation, e.g. yaqaʿ “it happens” (root w.q.ʿ) and yaxāf “he is afraid” (root x.w.f).

Following are extracts from our corpus, demonstrating the disharmonic patterns discussed hitherto in a more natural context:

i. qāl-lo: ismaʿnī yā-yihūdī. anā ḥabbētak, w-min maḥibbatī lak maqṣūdī minnak inn taslím min-šān tadxol algannah. qāl-lo alyihūdī: ṣaḥīḥ niʿlam inn annabī gālis fi-bāb algannah, lākin mā yiʿlam annabī inno fī ṭāqah qafāw w-minnahā yadxulū alyihūd algannah (YR)

He said to him: “Listen to me, Oh Jew. I like you, and because I like you, I wish that you convert to Islam so that you enter Paradise.” The Jew said to him: “True, we know that the Prophet sits at the gate of Heaven, but the Prophet does not know that there is a window above it/him, and through it the Jews enter Paradise.”

ii. yakūn yaxrog min alḥagar, min ʿarḏ̣ alharIHb … kān yaxrog almā min ʿarḏ̣ aḏḏāḥah, yarūḥū yikḥuIHb garrah yiṭraḥūhā (MY)

[The water] would run out from the mountain … the water used to run out from within the steep mountain, and they would go and take a jar and put it [in it].

iii. hū yiṭlaʿ b-algibāl w-almagnū́n baʿdo. yaštī yinhabo … mágnūn mágnūn! mašugaʿ IHb. yaštī yinhabo, yagrī baʿdo yaštī yinhabo (WḎ̣)

He was going up the mountains and the madman after him, aiming to rob him … a real madman! A lunatic. He wanted to rob him and was running after him, wanting to rob him.

iv. kān boh wāḥid yigzáʿ kull yōm yaṭlúb̥. boh wāḥidah gālis bi-ṭaráf alqaryah, yaqūl-le: yā maráh, indī-lī luqmah. taqūl-lo: boh mā boh, yā ibnī … māni-š fāriġ aqūm (ĠŠ)

There was a man who used to pass by every day and beg. There was a woman who was sitting on the outskirts of the village, and he would say to her: “Oh woman, give me some bread.” She would say to him: “I may or may not have it, my son, but I have no time to get up [and serve you].”

v. lak ʿuqmah lā taqdir tiblaʿ luqmah (ĠŠ)

May you become paralysed, and not [even] be able to swallow some bread.

Intriguingly, while the disharmonic distribution is by and large stable and consistent in spontaneous speech, in direct elicitation the scene appears to be more complex. In translating forms out of context, we encountered certain fluctuation in the use of a and i as V1, e.g. yagles and yigles, niḏbaḥ and naḏbaḥ. When asked for their grammatical judgments regarding the two options, the informants tended to approve both. This is most likely related to the fact that the language is not in daily use, and in addition the speakers are continuously and for many years exposed to forms and patterns from other varieties, not rarely even within the same family unit. One should also consider “biased” replies in elicitation based on translation from Hebrew, e.g. when an informant suggested tiqbor as a translation for Hebrew tikbor “she will bury”, as opposed to the expected dialectal taqber (indeed heard on other occasions). Further to the point of instability, see Section 4.3 below.

We find it noteworthy, that when confronted with the two forms alongside each other, e.g. yagles and yigles, and when directly asked about the difference between them, two of the informants (RṢ and MY) intuitively explained that the form with V1 = a indicates an action in the present, whereas the one with i bears the meaning of a future action. In the next paragraph, we account for this intuitive reasoning of the informants and show that it actually accords with the shift of a > i that occurs in the interaction of the preformative with the future prefix š(a)-.

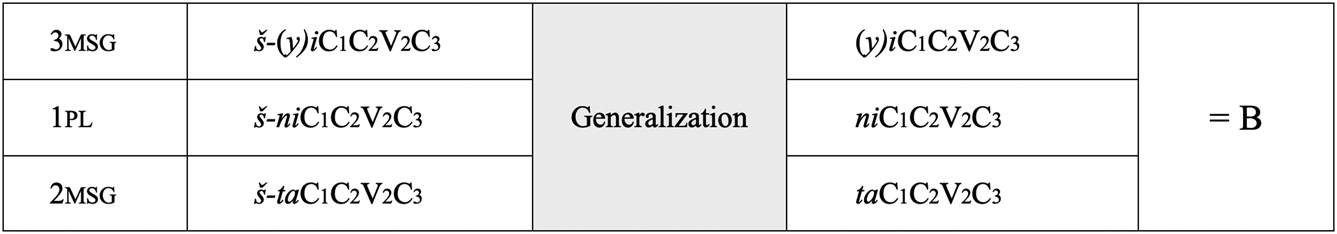

3.2. The shift in the interaction of V1 with the future tense marker

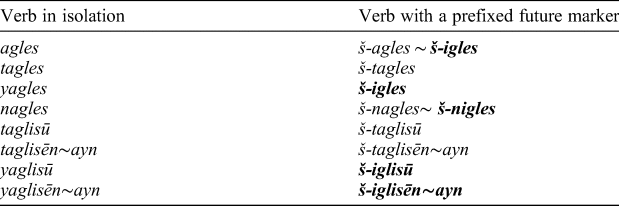

As noted, in the dialects of Ḥugariyyah, V1 surfaces as a in two of the three imperfect patterns, namely PaC1C2iC3 and PaC1C2uC3. This systematic patterning may, however, be violated under defined circumstances, i.e. in the interaction with the future tense marker š(a)-.

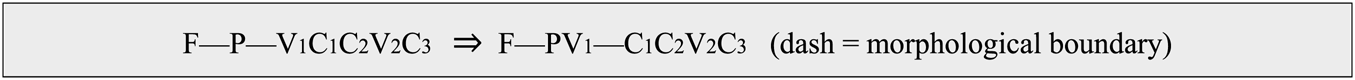

The future tense marker š(a)- probably has its origins in the Old Arabic verb šāʾa “want” (Behnstedt Reference Behnstedt2016: 235), and thus belongs with other future particles in Arabic that are derived from verbs and nouns indicating desire, a common phenomenon cross-linguistically (Bybee et al. Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994: 254–7; Zack Reference Zack, Edzard and Jong2011). Distinct from Ṣanʿāni Arabic, where ša- only occurs before the 1st person singular (Watson Reference Watson1993: 79), in Ḥugariyyah (as well as in other southern varieties) this future marker is used for all persons. Indeed, the interaction of ša – in Ḥugariyyah regularly š – with the various persons is what concerns us here, since its prefixation to V1 = a may yield a shift in the quality of the vowel: while in the interaction of š with P = t the preformative vowel invariably remains a, with P = y we observe that V1 = a shifts to i.Footnote 18 A similar shift was noted in a few cases with P = n, and instability was observed with the 1st person singular (see Table 3).Footnote 19

Table 3 The shift of a > i in the interaction with the future marker

Similar alternation has been documented with other verbal patterns and stems, as may be exemplified by yargom vs. š-irgom (ḤA, ASh) “he will throw” or yašūf vs. š-išūf (ShX) “he will see”. We also noted examples in certain verbal measures other than the G-stem, e.g. yaštaġilū vs. š-ištaġilū “they.m work” (RṢ). These shifts are summarized in Scheme 6.

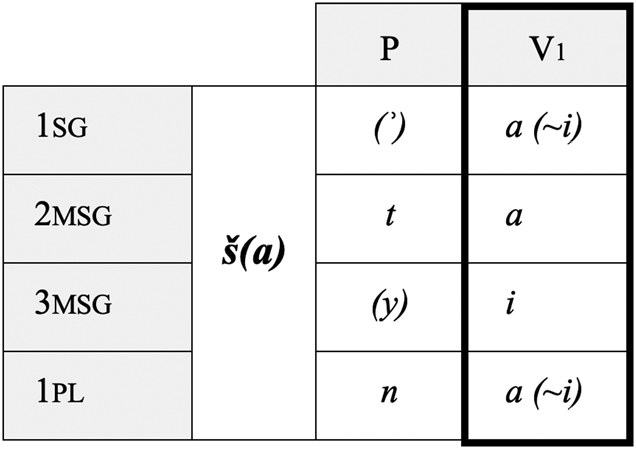

Scheme 6. Interaction of P with the future marker in Ḥugariyyah

Even more intriguing is the fact that following š we note that V1 = i is retained for all but P = t. With the latter, V1 shifts to a. Consider the examples in Table 4, using the root ṭ.l.ʿ “go up”:

Table 4 The shift of i > a in the interaction with the future marker

It thus becomes apparent that in this variety the quality of V1 is sensitive to the presence of the future tense particle. While the development of š(a)+ya ⇒ ši is expected phonetically, it does not take place in other Yemeni varieties: the future particle ša- is used throughout the western strip of Yemen, including the Tihāma and Lower Yemen (Behnstedt Reference Behnstedt2016: map 097), yet it is only in Ḥugariyyah that we observe the decisive effect of its interaction with V1 = a. Consider, for example, the form š-yarawwiḥū “they will return” that we recorded in Šarʿab. The fact that n may bring about a similar development is also not surprising, given that in other Semitic languages we also observe cases where n triggers a > i (see Step 2, Section 4.3). What is more crucial to our discussion is the shift of š+ti ⇒ šta, which does not seem to be phonetically motivated and, therefore, may be better explained in terms of morphological reanalysis. This hypothesis will be discussed in Section 4.3 below.

Before moving on, it seems noteworthy that the examined corpus offers only a few examples of the future tense marker in natural unaffected speech. As mentioned above, our corpus mainly consists of first-hand accounts of experiences, which typically take the form of past tense tellings. The future marker nevertheless occurs in the corpus in indirect speech, either when the narrator reports on verbal communication referring to a relative future, i.e. to a time located after the reference point of his/her account, or when referring to the future intentions of a character in the narrative. Consider the following additional extracts:

vi. qāl: ḏāḥīn, qūmī ya-rāziqah anā š-abīʿik. qāla: tabīʿanī yā-Muḥammad? nisīta samnī? qāl: anā qa-biʿtik w-astawfayt aṯṯamán (ĠŠ)

He said [to the cow]: “Now, get up, Oh Rāziqah [personal name], I am going to sell you.” She said: “Will you sell me, Oh Muḥammad? Have you forgotten the ghee butter [which you make from my milk]? He said: ‘I shall sell you and have my full share of the profit.”

vii. gissū tiḥt alʿēṣIHb w-hū qadam. w-anī ʿād-anī š-axrug, anī w-bintī ḤannōHbC, š-asīr (BA)

They sat under the tree, and he arrived. I was just about to leave, me and my daughter Hannah, to go.

viii. hī haraba qa-kāna bi-ḥublā. wulidá ʿinduhon … harrabunne la-ʿind addawlah, harrabunne la-ṯamm šallunne la-ṯamm š-išammidunneHbC (BA)

She escaped while she was pregnant and gave birth at [a Muslim village] … then they smuggled her there, they took her there in order to convert her to Islam.

ix. qāl: … ríddunne la-lqabr, w-xallunne ‘ala alqabr w-anton israḥū. qālu: inta magnūn? mā š-taʿmal inta? qāl: mā yaxussakon? (ĠŠ)

He said: “Take her back to the grave, leave her on the grave, then go.” They said: “Are you mad? What are you going to do?” He said: “It is none of your business.”

By now we have demonstrated that in certain phonological circumstances V1 = a may feature i. Scheme 7 gives V1 as it surfaces in the future-tense paradigm:

Scheme 7. The paradigm of the prefixed future marker

Thus, while the basic imperfect paradigm of Ḥugariyyah accords with Barth's Law and demonstrates a configuration of type D, the future paradigm of the same dialect partially resembles configuration B, where the quality of the vowels is said to be determined by the person. In light of this resemblance, we now turn to consider the interrelations between the four configurations A–D and to examine possible motivations for a historical change that may have resulted in the emergence of configuration B as a secondary development.

4. The interrelations between configurations A–D

In Section 1 above we surveyed the four configurations of the preformative conjugation found throughout the Semitic languages. This distribution evokes the comparative linguistic question of which of the four should be reconstructed to Proto-Semitic. Such discussions are, of course, speculative in their nature, and answering this kind of question relies to a large extent on methodological principles as to what is considered a better hypothesis for reconstruction. Although one cannot rule out the possibility that more than one configuration existed in the proto-language, it is still very unlikely. It seems more reasonable that some of these configurations should be accounted for as secondary. Discussions of this sort should therefore remain at the methodological level, and to focus on what is ultimately a valid argument in reconstructing the verbal system of a non-documented proto-language. In the case at hand, we would like to challenge the use of the principle of archaic heterogeneity in the context of the prefix conjugation, and to demonstrate how data from a living variety may shed light on the discussion of language antiquity. In doing this, we are following the uniformity principle formulated by the Neogrammarians, according to which all languages operate according to the same principles and forces, and we propose a possible consistent development. Notably, all steps of the proposed development are attested by data from present-day Yemen.

According to the principle of archaic heterogeneity (Hetzron Reference Hetzron1976: 93), “when cognate systems in related languages are compared … the relatively most heterogeneous system might be considered the most archaic”. In the case under consideration, it may be claimed that configuration B exhibits the most inner heterogeneity, and it has therefore been argued that it should be reconstructed to Proto-Semitic (Hetzron Reference Hetzron1976: 95; Hasselbach Reference Hasselbach2004). However, this guiding principle is only applicable where there is no obvious cause for the observed heterogeneity. In fact, it has already been speculated that configuration B, as attested in Akkadian, is secondary, and that it is the result of phonological interactions between the specific prefix (P) and the following vowel (V1).Footnote 20 While this proposal was, so far, rather speculative, the data from Ḥugariyyah allow us to actually witness the ongoing evolution of a person-determined distribution, i.e. configuration B, out of the inverse correlation of configuration D. The proposed development is represented in Scheme 8.

Scheme 8. Evolution of configuration B

Applying the ideas of the uniformity principle in the context of historical linguistics, we argue that a diachronic process that is established in a living language may be suggestive of similar processes in another ancient language. Therefore, we propose to consider that the development D ⇒ B that we observe in Ḥugariyyah may have taken place in Akkadian as well. Since the distribution of prefixes and vowels is similar in Akkadian (in the prefix-conjugation) and in Ḥugariyyah (in the future prefix), and since we can follow the evolution of the latter from a D-type distribution, we propose that the distribution observed in Akkadian may be the result of a similar historical change D ⇒ B. Moreover, since in the case of Ḥugariyyah the shift from D to B is motivated by the interaction with the future marker, the assumption that configuration B is unmotivated, and that it must be genuine and ancient, is no longer unequivocal.

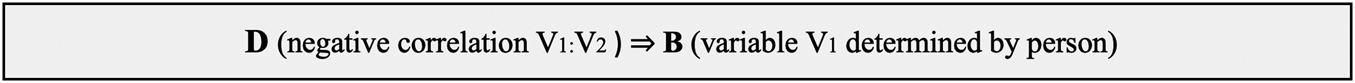

We therefore contend that configuration D is the most probable to reflect the situation in Proto-Semitic. While independent motivations for this claim were proposed elsewhere (see, e.g. Bar-Asher Reference Bar-Asher2009a), in what follows we demonstrate how each of the three configurations A, C and B may be derived from D.

4.1. The evolution of configuration A

As mentioned, many Semitic varieties exhibit an invariable V1, namely either a or i throughout the paradigm, for all/most roots. It has been suggested in various places that in these varieties one of the two preformative vowels has been levelled throughout the sound verb (see, e.g. Hetzron Reference Hetzron1976: 95). By means of analogy, these varieties shifted from a disharmonic distribution consisting of both a and i in negative correlation with V2, i.e. configuration D, to an invariable configuration with only one possible V1.Footnote 21 The proposed development is represented in Scheme 9.

Scheme 9. Evolution of configuration A

As a result of analogical processes all PiC1C2aC3 and PaC1C2iC3 / PaC1C2uC3 have become either PaC1C2V2C3 or PiC1C2V2C3 (with the exception of C1-gutturals that have hindered the change in several languages; see Section 2 under configurations A and D). Interestingly, in Arabian dialects that maintain internal (apophonic) passive as a productive morphological category, the generalized a-prefix allows a “slot in the paradigm” for marking the passive with i, at least in the case of transitive verbs, e.g. yasrig “he robs” vs. yisrag “he is robbed” (Al-Sweel Reference Al-Sweel1990: 72; Palva Reference Palva and Forstner1991: 161; Ingham Reference Ingham1994: 27).

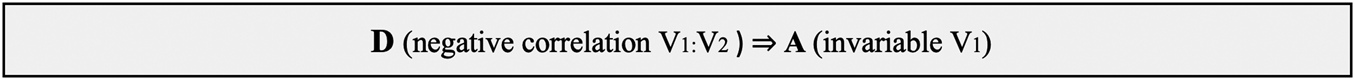

4.2. The evolution of configuration C

Positive correlation between V1 and V2 is plausibly the result of a secondary assimilation of V1 to V2. It may be assumed that these harmonic patterns followed from the evolution of a generalized V1, i.e. configuration A. The incidence of such harmonic patterns in geographically remote areas as North-West Arabia and the Maghreb, implies that these developments are not altogether recent (Palva Reference Palva and Forstner1991: 261). The proposed three-step process is presented in Scheme 10.

Scheme 10. Evolution of configuration A

For Arabic varieties that exhibit harmonic distribution, it may be assumed that V1 = a in PaC1C2V2C3 has assimilated to any dissimilar V2, yielding PaC1C2iC3 ⇒ PiC1C2iC3 and PaC1C2uC3 ⇒ PuC1C2uC3, in addition to PaC1C2aC3. Such a neatly arranged system, while existing in the aforementioned varieties (see Section 2 above), is not particularly widespread. An intermediate stage may be observed in dialects with a basic V1 = i that is subject to vowel harmony wherever V2 = u. A case in point is Jerusalem Arabic, which features the patterns PiC1C2aC3, PiC1C2iC3, and PiC1C2uC3 ⇒ PuC1C2uC3 (Bauer Reference Bauer1913: 21; Rosenhouse Reference Rosenhouse, Edzard and Jong2011b).Footnote 22

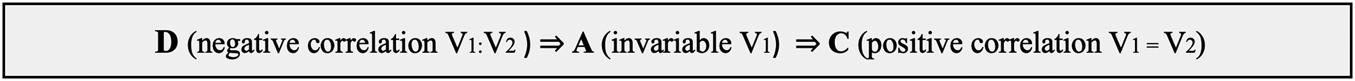

4.3. The evolution of configuration B

In light of all the above, we propose to account for the heterogeneous vocalization of configuration B, where V1 varies within the paradigm according to the person, as the endpoint of a four-step diachronic process:

Step 1: Inverse correlation

In this initial stage, the conjugational prefix structurally consists of the consonant alone, whereas the quality of V1 is determined by inverse correlation with V2. This state of affairs is represented by configuration D, characterizing the bare imperfect paradigm of Ḥugariyyah (see Scheme 11).

Scheme 11. Configuration D as first stage

Step 2: Phonetic shift

In the interaction with a preceding particle (hereafter: F), V1 = a shifts to i when P = y, namely F + yaC1C2V2C3 ⇒ FyiC1C2V2C3. This shift may also occur when P = n: F + naC1C2V2C3 ⇒ FniC1C2V2C3, but it never takes place with P = t (assuming that at this stage both F + taC1C2V2C3 F + tiC1C2V2C3 were available). Previous studies pointed to the phonetic motivation for the ya ⇒ yi shift (see Bar-Asher Reference Bar-Asher2009a for Akkadian, and Behnstedt Reference Behnstedt2016: 223 for Yemeni Arabic).Footnote 23 The shift of na ⇒ ni may be seen against the background of other Semitic languages where n tends to trigger i in certain cases (Hasselbach Reference Hasselbach2004: 33; Bar-Asher Reference Bar-Asher2009b: 60–1, n.50.) We argue, however, that the shift of Pa ⇒ Pi cannot be viewed as purely phonetic, given that in Ḥugariyyah it evidently takes place only in the interaction of P with a preceding F. Morphological considerations must therefore also be involved, as portrayed in what follows.

Step 3: Morphological reanalysis

The data from Ḥugariyyah reveal further, that in the interaction of F+P+V1 not only may Pa shift to Pi, but that the opposite also takes place, namely F + tiC1C2V2C3 yields FtaC1C2V2C3. Consider the distribution in Scheme 12, where the shaded areas correspond with Ḥugariyyah's future paradigm:

Scheme 12. Vowel shifts in the interaction of F + P+V1

While the shifts of ya > yi and na > ni could be justified phonetically, the same cannot hold up in the case of ti > ta. Rather, it is better accounted for morphologically, i.e. resulting from a process of reanalysis: in the interaction with the future prefix, V1 of the 3rd person has become invariably i, namely š-(y)i; then the prefix – structurally speaking – was reanalysed, and rebracketed as a combination of a consonant and a vowel (see Scheme 13).

Scheme 13. Rebracketing of the morphological boundary

Through morphological reanalysis, the quality of V1 in certain paradigms has become person-determined, disregarding the quality of V2: while the bare imperfect (i.e. without the future prefix) in Ḥugariyyah follows the old inverse correlation, featuring both ya and yi in the 3rd person and both ta and ti in the 2nd person, the future paradigm features a person-determined distribution with only š-(y)i and š-ta respectively.

As already mentioned in Section 3.1 above, however, we also observe certain hesitation in the quality of the preformative vowels in the bare imperfect. This is especially noticed in direct elicitation (as opposed to free speech), where informants may hesitate between tišrab and tašrab (MY), or yargom and yirgom (ḤA). As proposed above, this may reflect the continuous contact with both Israeli Hebrew and other Yemeni dialects, or the fact that the language is not in daily use. Moreover, in the present context it may also be taken to reflect a transitional phase between the systematic inverse correlation and a fully person-determined distribution, which is inherently characterized by instability.

Step 4: Generalization to the bare prefix conjugation

Following Step 3, where the quality of V1 has become person-determined in certain paradigms, we propose that the same distribution has been generalized to the “bare” paradigm, i.e. in the absence of F as well (see Scheme 14).

Scheme 14. The “bare” imperfect as the endpoint of a multi-stage process

In fact, the direction of the proposed development does not comply with Kuryłowicz's (Reference Kuryłowicz1949) second law, maintaining that “analogy proceeds from a base to a derived form”.Footnote 24 Notwithstanding, cases of back-formation (or reversion), in which the reanalysis of a derived form generates reinterpretation of the base, are well attested in historical changes (Lehmann Reference Lehmann1992: 231; Hock Reference Hock1991: 213–14).

The resulting person-determined distribution is indeed attested in a few Arabic dialects, as mentioned in Section 2 under configuration B. It plausibly accounts for the data from alMudawwar in Southern Ḥugariyyah (Behnstedt Reference Behnstedt2016: 223), reflecting a similar state of affairs, namely yiqtul vs. taqtul in the bare imperfect.

Finally, the person-determined distribution that characterizes the Akkadian paradigm may be viewed as the endpoint of a similar sequential development, starting from a distribution of inverse correlation that was followed by a morpho-phomenic shift in the interaction with F, yielding a new distribution. Then follows a reanalysis of the preformative vowels as integral to the prefix, and finally – the generalization of the new distribution to the bare paradigm. Akkadian indeed makes use of prefixes in the prefix conjugation, i.e. the vetitive and the precative, and also demonstrates phonological shifts in the interaction between F and V1 (Buccellati Reference Buccellati1996: 183).Footnote 25 The proposed analysis, deriving configuration B from D, implies a direct line connecting the Akkadian preformative conjugation with a former system, whose essential characteristic is V1 ≠ V2.Footnote 26

Notably, while the shift we observe in Ḥugariyyah involves the interaction with the future prefix, the process of phonetic change (Step 2) followed by reanalysis of V1 (Step 3) could have well been generated in the bare form itself, i.e. even without additional prefixation. The case of Ḥugariyyah allows us to trace the motivations for a sequential change, supporting the claim that heterogeneity may in fact be the endpoint of a diachronic shift. The heterogeneous distribution in Akkadian may follow from a comparable process, either in the interaction with prefixes or without it. In all probability, heterogeneity in this case does not indicate archaism.

5. Concluding remarks

In this paper we examined data in the Arabic dialect of Ḥugariyyah, where the basic imperfect conjugation complies with the disharmonic vowel distribution known as Barth's Law. The data from Ḥugariyyah not only provides a living demonstration of an extremely archaic feature, but also offers an opportunity to examine the behaviour of the verbal forms in natural context. In accordance with our findings in Ḥugariyyah, we trace the motivation for vowel shifts within the paradigm. We propose that similar motivation may account for a more general historical change that had eventually led to a person-determined distribution (configuration B), similar to that attested in Akkadian. By this we hope to have contributed to the longstanding debate in the literature over the nature of Barth's Law, as we demonstrate how one can consider the Akkadian preformative conjugation to be a derivative of the reconstructed Proto-Semitic distribution, and we challenge the use of the principle of archaic heterogeneity in this context.Footnote 27

The evidence for the historical development from configurations D to B was recorded in Yemen. We find it fascinating that all four configurations A–D are indeed represented in Yemen to this very day, as may be observed in Behnstedt-Reference Behnstedt2016 (map 093). Thus, the analysis of the preformative conjugation in Yemeni Arabic may be seen as a case of dialectal “apparent past” (Owens Reference Owens and Holes2018), where the various historical stages are all still apparent, co-exist synchronically, and may each be demonstrated in present-day living varieties.