In 1902, writing with characteristic intensity, the Viennese art historian Alois Riegl declared that the “problem of late antiquity” was the single most pressing concern in the entire history of mankind.1 By any reckoning, this was quite a claim, one that came in response to the negative assessment, historic and contemporary, of the period’s art. Ever since the sixteenth century, when critics such as Raphael and Giorgio Vasari had taken it upon themselves to pillory late Roman art for what they understood to be its complete disregard of the centuries-old classical representational canon in a blistering appraisal of the fourth-century reliefs on the Arch of Constantine,2 references to late antique visual production had summoned thoughts of disintegration and decline. Riegl’s immediate goal was to turn the tide of opinion by identifying and explaining the mechanisms behind late Roman visual production.

He had attempted to do just that in a recent publication, Die spätrömische Kunst-Industrie (The Late Roman Art-Industry).3 Against the claims of contemporaries, who, in keeping with Raphael and Vasari, had ascribed the transformation of Roman art to decline attendant upon the influence of external, barbarian forces, Riegl argued that the period’s process of artistic change was internally driven. The new style of late antiquity, which he characterized in formal terms as symmetrical, frontal, repetitive, static, and optic in contrast to the asymmetrical, animated, varied, and tactile forms of the earlier classical tradition, demonstrated the expression of a new attitude that had developed within the Roman Empire itself. Riegl saw this attitude and the style associated with it as deliberate and purposeful, a mode of expression that conveyed meaning through its appearances. Specifically, it represented access to the mind of late antique Rome, a mind that had turned away from the worldly engagement of classical culture to immerse itself in the concerns of magical transcendence.4

While the description and explanation of the logic of late antique art may have been his short-term enterprise, Riegl’s long-term goal was altogether more ambitious and all encompassing. As he saw it, the true value of late Roman art lay in the fact that it had created the conditions that would necessitate the Renaissance and with it the flowering of modern civilization.5 The real problem was to convince people of this truth. Although the aspiration to persuade viewers of late antique art’s pivotal role as the springboard for modern civilization gained no traction and has long since been forgotten, Riegl’s work did have profound and lasting impact. It effectively laid the foundation for what was to become an enduring interpretive paradigm for late antique art in scholarship and teaching.

That paradigm defines its materials in formal terms, arguing that Roman art in the period between the first century and the eighth follows a stylistic trajectory that moves from “naturalism” to “abstraction.” In this context, the categories of naturalism and abstraction refer to visual style, that is, to the way in which line, color, and composition are manipulated in a work of art and are understood to denote, respectively, the imitation of the world as we see it and the simplified interpretation of that same reality. The comparison between the first-century-BC sculptured reliefs of the Julio–Claudian dynasty on the Ara Pacis Augustae (the Altar of Augustan Peace) in Rome (Figure 1) and the sixth-century mosaic of Justinian and members of his retinue in the church of San Vitale, Ravenna (Figure 2), first mooted in the early twentieth century, has come to represent the classic demonstration of the change.6

1. Julio–Claudian procession, Ara Pacis Augustae, Rome, 13–9 BC.

2. Justinian and his retinue, Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, mid-sixth century.

In the Augustan relief, the Julio–Claudians – male and female, young and old – process along the two long sides of the altar. Figures carved in varying levels of relief fill the frame in three superimposed ranks, creating the sense of spatial recession. The children and heirs to the dynasty stand at the front, most fully rendered. Behind them in lower relief are the family’s major players. Still further back, merely sketched, are other, unnamed members of the procession. No two figures share the same pose, and the participants appear to shuffle forward, turn and converse, stop and start in the way of all such ceremonial events. The garments, wrapped and stretched in broad swaths and tight folds, interact with the bodies they clothe, confirming the sense of motion by creating a complex series of undulating lines that weaves in and out of the composition. With its emphasis on three-dimensional form, the appearance of spatial recession, and the sense of implied motion, the procession is seen to convey the look of the material world, and with it the experience of vitality and transience that stands at the heart of naturalistic representation.

The Justinianic mosaic, also depicting a procession, is a study in contrast. Justinian stands at the center of his retinue against a neutral green and gold ground. He carries a gold paten and sports the sartorial insignia of his office: the diadem, the purple chlamys with gold embroidered tablion, and jewel-encrusted red boots. A nimbus completes the look. To his left are members of the clergy; the bishop Maximianus, identifiable by inscription; and two deacons carrying objects for the celebration of the Eucharist: a censer and a codex. Court members appear to Justinian’s right and left. Still farther to his right are soldiers. In direct contrast to the serried rows of richly sculptured figures in the Ara Pacis reliefs, these figures are laid out on a flat plane: There is no sense of depth, volume, or motion, an impression enhanced by the shift to the mosaic medium. Although the faces are individualized and costume distinguishes the participants’ rank and status, each of the figures assumes the same frontal pose, confronting the viewer with only minor variation. The garments, which fall in wide blocks of color articulated by straight unbroken lines, not only underscore the planar composition but also create a sense of stasis. Further, the isocephalic arrangement of the heads and the compositional overlapping of figures who appear to collide and tread on one another’s feet make any sense of volume, space, or directional movement ambiguous. It is not clear whether the group moves forward in a V-shaped configuration with Justinian at the apex or toward the emperor’s left under the guidance of the clergy. These simplified, static forms, so planar and linear in their construct, define what is understood to be late antique abstraction.

Observing this shift is one thing, making something of it another. Following Riegl and his later interpreters, current understanding is premised on a formal polarity in which naturalism connotes the material world and rational thought, while abstraction conjures the immaterial world and spiritual experience. Correspondingly, this shift in appearances has been linked to a larger historical change, the turn from the polytheistic religious practices of Greco-Roman tradition to the monotheistic beliefs of Christianity, from antiquity to the Middle Ages.

As with all such generalizations, there is some truth to the observations of artistic form on which this broader understanding is based. From the late third century on, artists show a greater propensity for the use of this simplified manner of representation than they did in the first and second centuries, as demonstrated by a comparison of an early third-century image of the emperor Caracalla (Figure 3) and the porphyry portrait of a tetrarch from about 300 (Figure 4). The figures are similar in pose and iconography: In each, the head is turned sharply to the right, and both emperors sport the short hair and beard of a Roman military man. It is here, however, that the similarity ends. In the Caracalla portrait, the artist marshals all of his skill to sculpture a figure that seems to imitate natural form and movement. The short hair and beard are rendered in three-dimensional waves of tousled curls to frame a square face carved as a series of modulated, merging surfaces that capture the texture of skin and the shape of its underlying flesh. A completely different sense of artifice regulates the carving of the tetrarchic bust where a bold interaction between mass, surface, and line characterizes the whole. Three clearly articulated but integrated masses – the head, the neck, and the shoulders – establish the visual field. The raised, uniformly stippled surfaces of hair and beard contrast with the regular contours of the polished face on which a series of sharp, but thick, projecting lines defines and emphasizes the eyes and brows. This stark treatment, together with the strange color of the porphyry medium eschews naturalistic observation for a type of representation so reduced and simplified that even basic identification of the figure is unclear.

3. Caracalla, 212–217, Altes Museum, Berlin.

4. Portrait of a tetrarch, 284–304, Egyptian Archaeological Museum, Cairo.

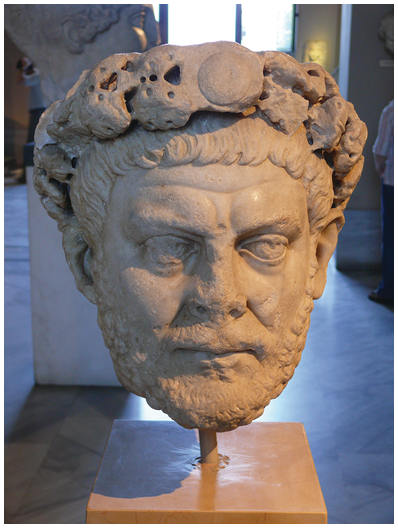

While the Caracalla–tetrarch comparison confirms a shift from naturalism to abstraction, it tells only part of the story. For example, a portrait of the emperor Diocletian (284–304), the architect of the Tetrarchy (Figure 5), which dates to the same period as the porphyry bust, shows an altogether different stylistic sensibility, one much more in keeping with the kind of representational tradition manifest in the bust of Caracalla. Here the cubic structure of the porphyry image gives way to a more emphatically “naturalistic” depiction. The bearded emperor, lips tight and hair tidy under a massive diadem, casts what appears to be a quick glance to one side. The creased and undulating surfaces of skin suggest living flesh and blood.

5. Portrait of Diocletian, 284–304, Archaeological Museum, Istanbul.

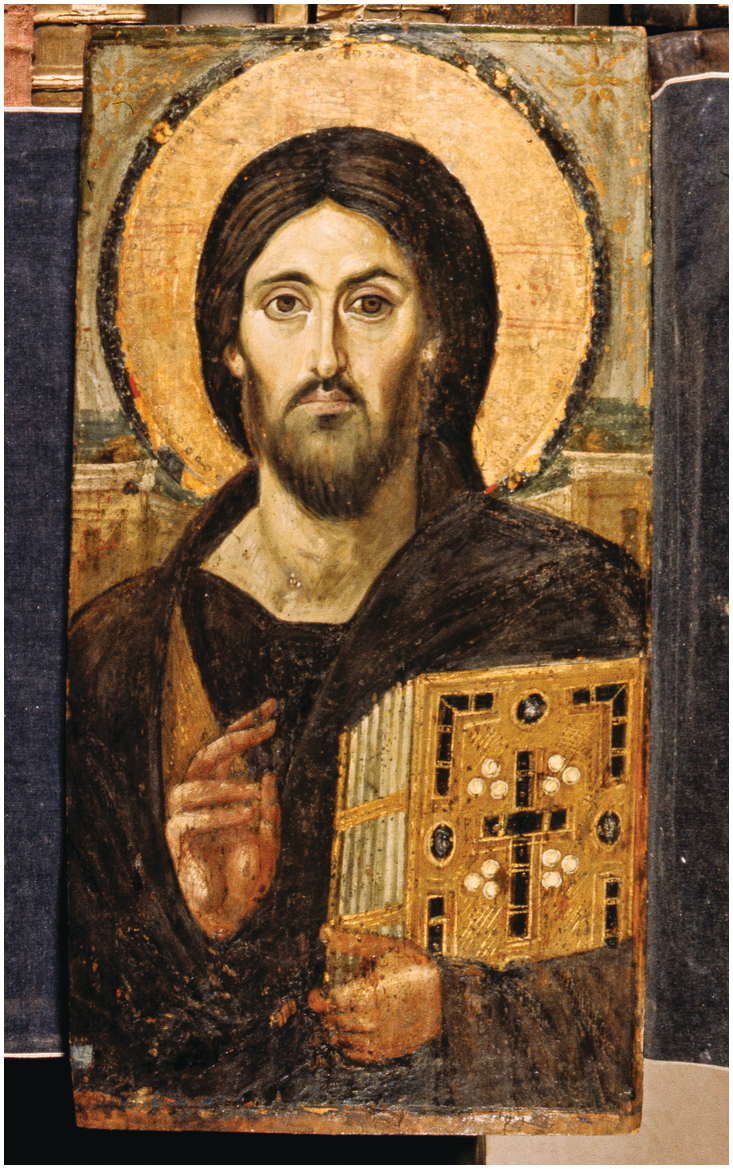

There is, further, ample evidence of the persistence of naturalism well into late antiquity, as indicated, for example, by two later works broadly dated to the sixth century: a personification from the border of the peristyle mosaic of the Great Palace in Constantinople (Figure 6) and an icon of Christ from the Monastery of St. Catherine at Mt. Sinai (Figure 7). As pictorial images, both the mosaic and the painting rely on two of the standard tactics of two-dimensional naturalistic representation: the modeling of figures in light and shade to create the illusion of three-dimensional form, what the ancients referred to as skiagraphia,7 and a corresponding sense of space and motion. Finally, a comparison of the icon with a contemporary image from Sinai, the apse mosaic of the Transfiguration of Christ (Figure 8), demonstrates that the styles described as natural and abstract continue to coexist. Here bold lines and broad swaths of color replace the careful modulation of form seen in the icon. This coexistence of styles calls the current paradigm into question by pointing to a more complex visual culture than that expressed by the standard model of change. It also suggests that the established associations drawn between styles, meanings, and cultural conditions are neither obvious nor necessarily correct and that the concepts of naturalism and abstraction as currently understood should themselves be examined and placed in context.

6. Head of a personification, Great Palace Mosaic, sixth century, Mosaic Museum, Istanbul.

7. Christ Pantokrator, sixth century, Holy Monastery of St. Catherine, Mt. Sinai.

8. Mosaic of the Transfiguration, sixth century, Holy Monastery of St. Catherine, Mt. Sinai.

Terminology also complicates the issue. While it is clear from literary sources that ancient viewers admired what we would call naturalistic effects and considered such representation as the end of art, there is no term for naturalism in the language of ancient art commentary. Instead, Greek and Latin authors speak of imitation (mimesis/imitatio or emulatio), and when they do, it is not axiomatic that they refer to the illusionistic replication of the natural world, in that imitation may also refer to the copying of earlier artistic models. More problematically, neither language includes a word to convey the idea of visual abstraction: Imagination (phantasia), not abstraction, often stands in contrast to imitation, although even it relies on an idea of imitation for its definition.8

This absence of terminology does not, of course, mean that the stylistic effects modern observers describe as naturalistic and abstract were not recognized or valued. It does, however, suggest that ancient viewers approached style from a different position and with a different understanding. This book is an attempt to explore this understanding. It does so by following two different paths of inquiry. Part I considers why and how late antique art came to be associated first with abstraction and then with spirituality. It begins by examining the origins of the style’s definition in fin-de-siècle Vienna. It then argues that before entering the mainstream, this particular understanding of the late antique style was conditioned by three factors: the contemporary politics of empire, the theory and practice of modern art, and a late-nineteenth-century interest in the occult sciences. Finally, it suggests that the formal definition of late antique style that emerged from Riegl’s pen was a modernist construct that had little, if anything, to do with ancient ways of seeing, much less absorbing, the lessons of form. With this conclusion in mind, Part II pursues an alternative approach to the understanding of late antique style by turning to the evidence for ancient and late ancient thinking about formal value. In an effort to reconstruct a late antique “period eye,”9 it harnesses the language of rhetoric, a discipline with a rich vocabulary of style. By drawing an analogy between visual and verbal form, it explores the ways in which varied approaches to form may have shaped late antique viewing habits and with them the response to the visual arts. As an approach, it builds on the belief that artists and their audiences were bound together in a reciprocal relationship forged by the universal traditions of Greco-Roman education (enkyklios paideia), traditions that shaped approaches not only to literary and visual understanding but also to the way of being in the world.

Further Definitions

Two common but elusive terms, neither of which has a fixed definition, stand at the center of these discussions – style and late antiquity. Clarification is therefore in order. Definitions of style, also referred to as form, slide between descriptions that signal the ways in which such elements as line, color, and composition come together in a work of art, those that include materials and manufacturing techniques in the equation, and still others that incorporate considerations of iconographical content.10 In this project, style refers to the formal aspects of a work of art, that is, to the manner of rendering form through the treatment of line, color, and composition. According to this definition, style can be associated with individuals, schools, and locations. With respect to the latter, it can be both local and universal. This choice reflects and is consistent with the definitions promulgated by ancient authors. It also reflects the emphasis on the formal understanding of style that guided the earliest discussions of late antique art.

The definition of late antiquity is equally mutable. Used first by Jacob Burckhardt to designate a span of approximately fifty years coeval with the third- and fourth-century reigns of the emperors Diocletian (284–304) and Constantine (305–337), its definition was dramatically expanded by the Viennese art historians studied here, first by Franz Wickhoff, whose nebulous references to late antiquity encompassed the Roman world of the later fourth and fifth centuries, and then by Riegl, who set the legalization of Christianity in 313 as its starting point and the coronation of Charlemagne as King of the Franks in 768 as its terminus.11 The precision of Riegl’s definition has never been equaled. Subsequent use of the term is often more in keeping with Wickhoff’s looser definition and may refer to any one of a number of chronological variations. For some today, late antiquity begins in the second century and ends in the sixth. Others include only the fourth and fifth centuries in their definitions. Still others use the third through seventh centuries as the chronological frame. Most recently, late antiquity has been defined as the first millennium of the Christian era.12 In this discussion, late antiquity indicates the period between the beginning of the fourth century and the end of the eighth century (300–800), a definition chosen for its consistency with Riegl’s explorations.

Style in Late Antique Art: The State of the Question in Brief

This project is hardly the first to tackle the question of style in late antique art. As the critiques by Raphael and Vasari indicate, the problem of assessing and explaining the stylistic shifts that took place in late antiquity was integral to the earliest art historical discussions. For both authors, the Arch of Constantine signaled decline because it was constructed from reused materials, and, although they readily admitted that some of these spoils were beautiful, their reuse stood as an indictment of the Roman artistic community. Effectively, the recycling of sculpture stood as evidence for the absence of competent artists in the city, a point of view confirmed by the fourth-century reliefs that had been made to complete the ensemble. They were, as Vasari put it, “goffissime,” exceedingly silly.13

The scathing dismissal of the arch and with it the fourth-century reliefs guaranteed that the first serious consideration of late antique material would be a long time coming. In fact, it happened only in the late nineteenth century in the work of Franz Wickhoff and Alois Riegl. As had Vasari, both viewed late antiquity as a period central to the understanding of the history of art; however, in contrast to their predecessor they rejected the framework of decline. Broadly speaking, their achievement, which will be dealt with in greater detail in the first part of this study, was threefold. Wickhoff was the first to argue that the ostracized visual arts of late antiquity should be viewed as Roman, while Riegl laid the groundwork for a definition of late antique style as abstract and spiritual. Together, they confirmed the idea that late antique art represented a transition from antiquity to the Middle Ages, an epoch generating a style to be considered on its own terms.

That viewpoint, consolidated in the first decades of the twentieth century, in turn laid the groundwork for a different discussion in the overlapping disciplines of archaeology and art history, one that considered the question of stylistic origin. Some saw the genesis of abstraction in provincial art, but there was no consensus as to which provinces. Although most pointed to a vague and generalized East as the likely source of inspiration, there were also partisans for the West. Others considered the problem of style from a sociological point of view, arguing that abstract form had its genesis in non-elite plebian art.14

Tied into the question of origin was the issue of function. Once abstraction had been pinpointed as the characteristic mode of late antique visual expression, there was a further effort to explain its success. Ormond Dalton (1866–1945) and Charles Rufus Morey (1877–1955) agreed that the emergence of abstract form lay in its capacity to express spiritual transcendence and connected that ability to an eastern penchant for the mystical.15 This type of generalized understanding was further honed. For example, André Grabar (1896–1990) modified the equation between abstraction and spirituality to explain the character of late Roman and Byzantine imperial images by arguing that the stylized, frontal depictions of later Roman emperors emphasized details of costume over individual physiognomy to create a detached and symbolic image of divinely bestowed imperial power.16 In a similar vein, H. P. L’Orange (1903–1983) connected the forms of late third- and early fourth-century art and architecture to a contemporary spiritualization of ancient life.17 Others understood the severity of third-century form less optimistically, arguing that the stylistic shift was an expression of anxiety.18

Although all agreed that late antique style was abstract, the question of naturalism continued to nag, if for no other reason than the fact that an ever-growing body of evidence indicated an enduring attraction to such form. In a scholarly world in which style was understood as a developmental phenomenon that proceeded from a baseline of abstract, primitive form through a rising arc of increasing naturalism that eventually returned to abstraction this persistence of naturalism required explanation. As a result, theories designed to account for its tenacity began to emerge, with some scholars arguing that it represented a survival and others seeing it as a revival. Whether favoring revival or advocating for survival, these theories introduced an important new wrinkle by specifically aligning naturalism with the classical or Hellenistic tradition. In this context, naturalism was often explained in sociological terms as the reflection of late pagan religious allegiance.19

There were no conclusive answers to any of these questions, but in spite of disagreement all participants came together on one issue, the nature of stylistic development. Whatever their stance, all argued from the point of view that visual style developed along a trajectory that moved inexorably from origins in primitive abstraction through a peak in naturalism that then unraveled into abstraction and decadence.20 In other words, late antique art, a tradition in transit between antiquity and the Middle Ages, was going somewhere.

These debates were never firmly resolved, and questions of style continued to engage scholarly imagination until the mid-1970s when Ernst Kitzinger (1912–2003) and Kurt Weitzmann (1904–1993) produced two independently conceived overviews of late antique and early Byzantine art that seemed to offer the final word on the subject. The projects appeared at the same moment, in 1977. Kitzinger’s came in book form as Byzantine Art in the Making: Main Lines of Stylistic Development in Mediterranean Art, 2nd to 7th Centuries, while Weitzmann’s took shape as an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and its accompanying catalogue The Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Centuries. Both projects were the fruit of a lifetime’s engagement with the visual material and the scholarly tradition interpreting it. As such, each represented a personal assessment of the state of inquiry into the matter of late antique stylistic development as it had played out over the course of the twentieth century. They also cemented the understanding of late antique art.

Ernst Kitzinger and Byzantine Art in the Making

Byzantine Art in the Making represents Kitzinger’s sustained meditation on the transformation of style in the passage from antiquity to the Middle Ages, a subject that had occupied his scholarly attention since his days as a graduate student in Germany in the 1930s.21 Although he acknowledged the importance of iconographical research, his own proclivity was to approach late antique art through the matter of form. Thus, Byzantine Art in the Making puts style at the center of the conversation, identifying and analyzing its components, exploring its origins, considering its contexts, and examining its potential to generate meaning.

In many respects Kitzinger’s work represents a summation of twentieth-century thinking. As had been the case in art historical circles since the publication of The Late Roman Art-Industry, Kitzinger identified the period as an age bridging the gap between the Greco-Roman world of classical antiquity and the Greek and Latin Middle Ages, a period of transition that ran between the third century and the seventh.22 Its main stylistic components were two: the classical or Hellenistic style of Greco-Roman tradition, a manner of visualization rooted in naturalistic representation, and a non-classical, or abstract, style characterized by the schematic approach to form and space. Where Kitzinger differed from his predecessors was in his view of the relationship between these styles. While others saw stylistic development as a direct progression from naturalism to abstraction, Kitzinger presented the history of late antique form as one of interaction – what he referred to as a “dialectic” – between styles.23

This dialectical history begins with crisis: the collapse of the classical canon in the Tetrarchic and Constantinian art of the late third and early fourth centuries.24 It then sees the revival of classical tradition in the later fourth century,25 followed by the eruption of a new strain of abstraction in the decades framing the year 500.26 A new wave of classicism washes over the abstract currents of the late fifth century to create a synthesis between these polarities in the sixth century;27 however, this accord between opposites represents only a brief interregnum, and there follows a return to the polarization of classical and abstract forms around 600.28 Finally, a second, enduring synthesis between Hellenistic and abstract form emerges in the mid-seventh century at the threshold of the Middle Ages.29

Kitzinger’s primary effort was to explain the uses of style. To this end, he offered two interlocking proposals. The first was a theory of “modes.” Drawing on the language of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance musical theory, which categorized sound according to harmonic and rhythmic structures that were themselves associated with ideas and emotions, Kitzinger observed the coexistence of two visual styles in late antiquity, describing them as modes. Each mode embodied its own stylistic conventions, conventions determined by subject matter and possessing the ability to describe different levels of existence.30 Kitzinger’s modes corresponded to the two established categories of modern analysis, the classical or Hellenistic style of Greco-Roman tradition and the abstract, nonclassical style that grew up alongside it. In this dualistic scheme, works associated with the classical canon embodied tradition and conveyed a sense of the ideal. The proper subject matter of the classical mode was mythology, but classical form could also be deployed for imperial portraits to evoke a sense of retrospection and, in a twist, would eventually be used to convey the spiritual transcendence of sacred figures in later Christian painting.31 By contrast, the abstract mode, whose subject matter was imperial and religious, carried with it an emotional intensity, one that expressed everything from anxiety to superhuman imperial power to saintly otherworldly existence.32 As these characterizations suggest, these definitions were not airtight, with the result that they sometimes bled into one another, allowing the modes to achieve similar ends.

Whatever its difficulties, the theory of modes represented the first serious attempt to explain the stylistic contradictions of late antique art. Unlike his predecessors, Kitzinger rejected the idea of a direct, teleological development. Specifically, he viewed the process of change as a conversation, in which classicism and abstraction coexisted and interacted. They did so in dialogue with one another across time and space, sometimes operating in independent states that challenged one another, sometimes coming together to complement each other in great moments of visual synthesis.

Among the problems that interested Kitzinger as he observed this interaction was the question of creative impulse. The theory of modes required the deliberate selection of specific stylistic solutions. As a result, it raised the question of artistic agency: In a world of modal composition, what say, if any, did an artist have in the creation of form? In search of an answer, Kitzinger turned to the language of modern sociology, borrowing two terms from the work of the sociologist David Riesman: inner-directed and other-directed.33 Riesman had coined the terms to describe the mechanisms by which societies regulate behavior. Inner-directed behavior, characteristic of early modern, preindustrial society, was that in which individuals had so thoroughly internalized group values that they became their own. Other-directed behavior, evident in the modern industrial world, was that in which individuals looked outside of themselves for affirmation. Kitzinger modified these sociological definitions to describe the impulses directing artists. Inner-directed artistic form was that rooted in an internalized sense of the collective aesthetic. By contrast, other-directed artistic form resulted from the imposition of external will, such as the directives of a patron, upon an artistic project. In Kitzinger’s scheme, inner-directed and other-directed behaviors were not mutually exclusive.34 As with the styles themselves, each worked in dialogue with the other to shape the forms and directions of late antique art.

Kitzinger’s developmental model was complex. Late antique art presented itself as a great double helix in which strands of classical and abstract form spiraled around a shared vertical axis, sometimes as distant threads, at other times intersecting points, and always linked by the horizontal bridges of the modes. What this solution offered was a revised sense of the passage from antiquity to the Middle Ages. Specifically, Kitzinger placed new emphasis on Hellenistic form in late antiquity, arguing that the dialectic between classical and abstract concluded with the emergence of an abstract and spiritualized classical style by the middle of the seventh century. Thus, the greatest achievement of the late antique transitional age was the preservation of the basic elements of classical form against the repeated onslaughts of nonclassical tradition.35

In restoring the preeminence of the Hellenic, Kitzinger offered a solution to a problem that had plagued scholarship ever since Riegl first took up the question of late antique style: the dissatisfaction with abstract form. Riegl had legitimated abstraction by describing it first as an internal development of Roman art and then as the visual manifestation of thought. Later scholars elaborated on this connection between form and meaning to make abstraction the vehicle for the expression of Christian spirituality. While this line of thinking may have explained what was understood to have been the dominant formal quality of late antique art, it did not make it lovable. Virtually every scholar grappling with the description of late antique art in the twentieth century lamented the passing of the classical tradition. Riegl himself found the material ugly,36 and the American scholar Charles Rufus Morey, who did so much to advance the cause of late antique and early Christian art, was unequivocal in his conviction that the art of classical and Hellenistic Greece remained unsurpassed in human history.37 His German contemporary Gerhard Rodenwaldt (1886–1945) looked longingly for classical renaissances,38 and Kitzinger’s own description of the interaction between classical and abstract form used the language of crisis and struggle to suggest distaste for the assault on classical style.39 By observing and insisting on a role for Hellenic form in late antiquity’s final synthesis, Kitzinger sought to reconcile the perceived tension between classicism and abstraction. Coming full circle from his introductory crisis, his was a restorative act, one that aimed to preserve the classical heritage and the values of truth, beauty, and reason associated with it in a changed world.40

Kurt Weitzmann and The Age of Spirituality

If Byzantine Art and the Making appeared as a capstone to twentieth-century thinking about late antique art in an academic context, it was an exhibition, The Age of Spirituality at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, that brought the period stunningly to life for modern viewers. The exhibition, which opened in the fall of 1977, was the brainchild of Kitzinger’s older contemporary, Kurt Weitzmann, who also had trained in Germany. Like Kitzinger, Weitzmann understood late antiquity as a transitional period that bridged the gap between pagan antiquity and the Christian Middle Ages. His purpose in the exhibition was to make that transition tangible. To that end, he and his colleagues brought together a staggering number of objects, 450 in all, from the former territories of the Roman world.41

The materials were organized in five thematic groups, or “realms,” in order to convey the range of late Roman visual experience both synchronically and diachronically. The first, the “Imperial Realm,” included 109 objects and concentrated on the display of official images, everything from monumental portraits in marble and bronze to small-scale ivory diptychs commemorating Roman officials. It also included scenic representations of imperial activities, among them depictions of ceremonies and warfare across a range of media monumental and minor.42 The second, the “Classical Realm,” included 248 objects associated with pagan mythology, science, and poetry.43 The “Secular Realm” made up the third part of the exhibition with ninety objects, showing representations of daily life together with objects of daily use.44 The “Jewish Realm,” with eighteen objects, followed with a focus on representational art designed to provide a background for the fifth and largest of the groups, the “Christian Realm.”45 Here the display of 236 objects, with dates ranging from the third century to the seventh century, described the development of early Christian art. Sarcophagi, illuminated manuscripts, ivory carvings, and ecclesiastical plate documented the use of Old and New Testament themes as well as those with sources in apocryphal texts and traditions. The exhibition also considered varieties of representational strategies, narrative and iconic formats among them. Photographs of monumental apses and late antique holy sites were included in the exhibition, as were altar implements, reliquaries, and examples of church furniture.

While the make-up of the exhibition was chronological, numbers gave the visual narrative a particular slant, as did the nature of the themes treated and objects included within each of the realms. In terms of quantity, the Christian realm was by far the largest. Its story was also the most impressive. The display conveyed a sense of destiny, as humble objects, such as the modest lamps marked with Christian symbols that spelled out the first tentative beginnings of the faith, gave way to a range of small-scale luxury goods associated with the liturgy and the monumental mosaic programs of Christian churches designed to frame liturgical performance. By contrast, the arts of the imperial and classical realms could not hold a candle to those in the sphere of Christian production. Their numbers were smaller, and there was no sense of ongoing production. As for the secular and Jewish realms, the number of objects was negligible. Secular objects offered a contrast to Christian works, and works of Jewish manufacture were presented as the prelude to Christian production. As The Age of Spirituality made clear, late antiquity was the era of Christian triumph.

Style had its place in the march to Christian victory. Writing in the introduction to the exhibition catalogue, Weitzmann observed a centuries-long transformation of classical art according to a familiar formula: Between the third and the seventh centuries images passed from “the realism of bodily forms to the abstraction of more spiritual forms.”46 Abstract style, he opined, was not solely the stuff of “folklore and barbarians”; it was evidence of a desire to achieve a higher degree of spirituality than could be attained through naturalistic expression, and that desire was the hallmark of the period.47 Late antiquity was, as the title of the exhibition proclaimed, the Age of Spirituality.

The Staying Power of an Interpretive Trajectory

Although it has been some time since the subject of style took pride of place in the study of late antique art, the imprint of this tradition remains visible. Jaś Elsner’s influential study, Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity (Reference Elsner1995), published nearly two decades after Kitzinger and Weitzmann completed theirs, shares many of their basic assumptions. Elsner’s aim was to understand late antique art and the changes in style that emerged in the Roman world from early to late, not by parsing visual form but by examining the “conceptual frames” that shaped habits of viewing. To this end, he argued that Roman literary sources described two different approaches to works of art – the “literal” and the “symbolic” – two paths to visual understanding that existed side by side throughout the course of Roman history, each reflecting the experience of a distinct representational style. Thus, literal viewing governed the response to naturalistic representation, symbolic viewing the approach to abstract traditions.48

Elsner recovered these ways of seeing through an analysis of two major sources, the descriptions of paintings by Philostratus the Elder (170/172–247/250) known as the Imagines and an anonymously authored text from the first or second century, the Tabula of Cebes. In the former, Philostratus describes a series of mythological paintings. In the latter, the anonymous author deciphers an allegorical representation of human life on a votive tablet. Elsner associates each of these texts with a type of viewing. Thus, Philostratus’ description demonstrates the phenomenon of literal viewing, an experience of seeing in which the image is taken at face value and understood stylistically as a recreation of the natural world and its structure. By contrast, the Tabula of Cebes is an evocation of symbolic viewing, a habit of seeing that looked beyond actual appearances to see hidden truths in physical form. Implicit in the analysis of the Tabula is the sense of symbolic viewing as a response to abstract form. In addition, each of these viewing modes operates within a cultural context. Literal viewing is the province of secular engagement, while symbolic viewing aligns with the experience of the sacred. Finally, the traditions align with religious experience so that literal viewing becomes the perceptual frame of pagan tradition, symbolic viewing the matrix for Christian habits of seeing.49

Art and the Roman Viewer is not a book about style. Most of its discussion centers on the seeing and interpretation of iconography, and there is very little description or analysis of visual form in the manner of Riegl, Kitzinger, or Weitzmann. That said, the concept of style is ever present, hovering in the background of each discussion. What is interesting and important is the way in which Elsner understands this foundational concept. For him style is either naturalistic or abstract, and its individual visual dispositions correlate to meanings that can be associated with experiences of the secular or the sacred, the pagan and the Christian. Further, in common with his predecessors, Elsner understands that art in the period between the first and sixth centuries is moving along a visual trajectory that ends in abstraction.

Although different in kind, attempts to characterize late antique art emerge as strikingly similar in substance. All understand style as a dualistic phenomenon: naturalistic, on the one hand, and abstract on the other, a bifurcation of viewing habits that can be shown to have derived from nineteenth-century theoretical models.50 Ideas about stylistic development are integral to this understanding. Even in the context of Kitzinger’s dialectical approach, style moves along a developmental trajectory from naturalism to abstraction, antiquity to the Middle Ages. Because this is the case, style also functions as a chronological marker in which place is signified by the degree to which a work of art conforms to the tenets of one or another of the two poles. This model, which, as will be suggested, runs counter to the evidence of Roman art in general and late antique art in particular, perpetuates a belief in the perfectibility of stylistic development that ultimately can be traced to Vasari and his dictum that the arts “like human bodies are born, grow up, become old and die.”51 It is an uneasy fit.

New Approaches

This book is an attempt to tailor this ill-fitting suit. In an effort to refine the measurements, it sets aside the idea of late antiquity as the separate, transitional period it has become, to begin, as Wickhoff and Riegl did, by thinking about late antique art in the context of an ongoing Roman tradition. However, in contrast to their work, it acknowledges the pluralism of Roman tradition and the idea posited by Otto Brendel (1901–1973) that the simultaneous appearance of different styles in Roman art was the result of an association between form and meaning.52 Subsequent studies by Tonio Hölscher, Ellen Perry, Michael Roberts, and Henry Maguire have refined this view by connecting first Roman and then Byzantine artistic production to literary understanding. As did Riegl and Kitzinger before them, all work from the understanding that form is a bearer of meaning. At the same time, these more recent scholars proceed with a different understanding of the relationship between appearances and expression. Whereas previous studies have presented style in terms of the imagined polarities of naturalism and abstraction, these studies open the door to a range of formal possibility and meaning.

Hölscher has described the Roman manipulation of style as a “semantic system” in which a broadly understood, ever-evolving set of forms marshaled different stylistic approaches to express different types of meaning as appropriate to the subject.53 Derived from the Greek representational canon, those forms eventually took on an expressive life of their own within the Roman context. Thus, classical forms akin to the art of the Parthenon frieze or the Julio–Claudian processional frieze on the Ara Pacis represented a restrained, dignified style appropriate to state ceremonial,54 while the more exuberant, densely packed style of a first-century BC copy of Philoxenus of Eritria’s Battle of the Issus from the House of the Faun in Pompeii recalled late classical and Hellenistic styles and, through them, expressed the turmoil and pathos of battle.55

As Hölscher suggests, such visual usage finds parallels in ancient historiography and the genres of rhetorical declamation,56 a proposal expanded upon in work by Ellen Perry, who takes on the problem of style in a discussion of the Roman practice of emulating works of Greek art. Using the evidence of literature together with treatises on rhetorical theory and practice, she develops a theoretical framework that describes the practice of emulation with reference to specific literary and rhetorical concepts. Specifically, she explains the plurality of styles in Roman art by observing that the concept of decorum (appropriateness) demanded a correlation between style and subject, a requirement that led artists to deploy a varied stylistic palette, one that had nothing to do chronology or with such modern organizing concepts as naturalism and abstraction.57

If Hölscher and Perry have made sense of the broad patterns of Roman style through the end of the early imperial period by looking broadly at the relationship between word and image, Michael Roberts has taken a similar approach with the art of late antiquity by drawing visual form into a relationship with late Roman poetry and poetics. Unlike Hölscher and Perry, Roberts does not concern himself with the phenomenon of stylistic plurality. Rather he explores one aspect of late Roman literary expression, the episodic structure of late Roman poetic narrative, and with it the taste for detailed exposition and diversion, a habit he links to contemporary practice in the visual arts.58

Finally, no discussion of the relationship between word and image in late antiquity can proceed without acknowledging the seminal work of Henry Maguire. Maguire has demonstrated the ways in which the sermons and hymns of the Orthodox tradition fed the imagination of artists across the span of Byzantine history. On a basic level, he has articulated how artists developed new iconographies in response to literary embellishments of bare-bones Gospel stories. In addition, he has argued that these images bear a more profound relationship with rhetorical tradition, one in which the visual solutions arrived at by artists share the narrative styles and structures of spoken and written language. Finally, by exploring these strategies, he has drawn attention to the aesthetic aspects of Byzantine art and the relationship between style and meaning.59

The impact of Maguire’s work is evident in the flowering of studies devoted to the examination of the relationship between word and image that has come in its wake. The many essays by scholars such as Jaś Elsner, Liz James, and Ruth Webb have transformed the understanding of the rhetorical genre of ekphrasis.60 Once disparaged as overwrought and uninformative, these descriptions are now seen more broadly as illustrative of late antique and Byzantine attitudes toward representation. Others, such as Antony Eastmond, have explored the evocations of rhetorical styles in individual works of art.61 In short, Maguire’s work has given rise to a new approach to and understanding of late Roman and Byzantine art.

The study of the relationship between word and image that has captured the interest of scholars in the fields of Roman and Byzantine art is part of a broader inquiry into the correspondences between verbal expression and visual form that has come to the fore in the last half century in ancient, medieval, and early modern studies. Spearheaded by the work of Michael Baxandall in the 1970s, this inquiry has made modern viewers cognizant of the ways in which the visual arts in any given period are embedded within an imaginative universe shaped by such diverse, yet interlocking, experiences as religion, trade, law, and education. Baxandall’s exploration of the relationship between literary composition and pictorial representation in the work of the early Italian humanists and contemporary painters such as Gentile da Fabriano and Giotto articulated the correspondences between verbal and visual patterns of thought in artistic production, arguing that the similarities between them were the result of a common experience of language and the concepts it articulated.62 His point was that learning shaped both the expectations of and response to the visual arts as well as the creation of the visual arts. Charles Radding and William Clark’s joint study of the rapport between architecture and learning in the Romanesque and Gothic periods in western Europe followed a similar path by drawing analogies between developing conceptions of architectural design and intellectual argumentation in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.63 Similarly, Mary Carruthers64 and Paul Binski65 have explored the relationship between the visual arts and rhetorical composition in the Gothic period, while Caroline van Eck66 has extended these types of observations to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In spite of their chronological range, all of these works build on the shared understanding that visual form is of a piece with a broad range of concepts that shape society and direct expectations.

Given the richness of these studies, a reader might reasonably wonder what this project adds to the conversation. To begin with, it clarifies the extent to which the reigning definition of late antique style was the product of a distinct historical moment. While others have connected Wickhoff’s and Riegl’s overall interest in the art of the later Roman Empire with Austrian imperial ambitions,67 this study is, to the best of my knowledge, the first to suggest that the formal characterization of late antique style as abstract resulted from and was intended to support these ambitions.

Having observed the circumstances under which the interpretive model came into being, the book goes on to suggest a new critical language with which to examine late antique painting and sculpture, one consonant with the period itself. Building on the broad connections between verbal and visual form established in previous studies, this project proposes a more direct analogy between the two, for example, between verbal cadences and visual lines. In order to make these connections, it suggests that, given the status of rhetoric as one of the mimetic arts, the manifold and sometimes overlapping categories of style described in ancient rhetorical writing offer a language applicable to the discussion of painting and sculpture.

The point of exploring this language is to attempt to reconstitute a view of style that more closely approximates late antique understanding. That view saw style as something integral to the work of art. It was linked to subject matter, and, as ancient commentary makes clear, it operated within a mimetic framework in which the possibility for variation was enormous. By contrast, when Wickhoff and Riegl described late antique art, they understood style to exist independently of subject matter. It was a phenomenon that operated progressively within broad historical cycles that swung between the poles of naturalism and abstraction. For them, style was a unitary, autonomous expression of a cultural moment.

This project aims to recapture something of the ancient point of view. To do so, it relies on modern methods of formal analysis as a way into seeing beyond the customary categories of naturalism and abstraction. Such an approach is not without its critics. Initially developed as a neutral, “scientific” method to analyze works of art, formal analysis has been shown to have its own evaluative biases, and it is clear that the disinterested eye does not, and probably cannot, exist.68 Moreover, it was exactly this kind of study that led Wickhoff and Riegl, pioneers in the enterprise, to their own conclusions. Allowing for these truths does not, however, invalidate the enterprise. However imperfect modern analytic practices may be, they allow the possibility of seeing style in new ways, and seeing style is no small thing. As the ancients understood, and as this book argues, style was an essential means of communication. Therefore, to understand late antique style is not only to understand more fully the meanings that surviving images were designed to convey but also to grasp the habits of mind that shaped late antique experience.