Introduction

One of the main features of slavery in Brazil was that slaves had a better chance of achieving freedom than was the case in other slave societies. However difficult freedom may have been to obtain, significant rates of manumission resulted in a high percentage of free and freed people of color in the population of the country throughout the nineteenth century.

Nevertheless, much remains to be known regarding the experience of freedom for freed people and their descendants while slavery still existed. This article seeks to analyze facets of what I will denominate the structural precariousness of freedom in nineteenth-century Brazil. Thus, I will deal with such themes as the constitutional restrictions on the political rights of freed persons; the masters’ interdiction of their slaves’ learning how to read and write; free and freed blacks’ very limited access to elementary schooling; the practice of granting conditional manumissions; the masters’ right to revoke liberties; the illegal enslavement of free people of color; and police profiling and arrest of free and freed blacks under the allegation that they were suspected of being runaway slaves. In approaching all these complex themes very briefly, the idea is to highlight situations which often blurred the distinction between slavery and freedom in nineteenth-century Brazil, therefore rendering insecure the condition of free and freed people of African descent.Footnote 1

Figure 1 Nineteenth-century Brazil: provinces and cities cited in the text.

Comparing data on the free population of color in Brazil, Cuba, and the United States, the three main slave societies in the Americas in the nineteenth century, helps to bring our subject into relief. According to the Brazilian census of 1872, the only national census carried out before the abolition of slavery in 1888, the country had 9,930,478 inhabitants, of whom 8,419,672 were free (84.7 per cent) and 1,510,806 remained slaves (15.2 per cent). With regard to racial composition, 38.1 per cent were white, 19.7 per cent black, 38.3 per cent pardos (mixed race) and 3.9 per cent Indian. Blacks and pardos together, including all social conditions (free, freed, and slave) comprised 58 per cent of the total population (5,756,234 people). Slaves excluded, the free population of 4,245,428 people of African descent represented 42.7 per cent of the inhabitants of the country, just about the same number of people deemed white in the 1872 census.Footnote 2

In Cuba, according to historian Rebecca Scott, the total population reached 1,389,880 in the early 1860s, of whom 57.1 per cent were white, 26.6 per cent slaves, and only 16.2 per cent free blacks – a sharp contrast with the 42 per cent in this category in Brazil at about the same time. According to the same author, in the state of Louisiana, in 1860, just before the beginning of the American Civil War, the population consisted of 708,002 inhabitants, of whom 50.5 per cent were white, 46.8 per cent slaves, and just 2.6 per cent free people of color, and those were very concentrated in the city of New Orleans.Footnote 3

Another way of pondering this sort of data is to focus on the relative presence of free people of color in the total population of African descent. Thus, in 1872, 73.7 per cent of blacks and pardos living in Brazil were free.Footnote 4 In the United States, in 1860, Ira Berlin found that no more than 11 per cent of the population of African descent were free; this figure included data from the northern states, where slavery had virtually disappeared and which registered 99 per cent of their colored population as free. Regional differences remained important in southern slavery – in the Upper South (Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, etc.), 13 per cent of the people of African descent were free; in the Lower South (South Carolina, Georgia, Florida), 2 per cent; in the Deep South (Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Texas), 1 per cent.Footnote 5

These brief comparisons of population data for Brazil, Cuba, and the US in the nineteenth century lead to two observations. First, slave societies in the Americas seemed extremely diverse with respect to opportunities for obtaining manumission. In the US South, the overall tendency was for masters to lose the right to grant freedom as slavery expanded and the national split over it deepened.Footnote 6 In some states, as in Alabama, for example, masters who wished to manumit slaves had to petition the state legislature; as a consequence, in the period from 1829 to 1839, the local assembly authorized the granting of freedom to approximately 200 slaves, while Alabama had 120,000 people held in bondage in 1830. In the 1850s, several states prohibited masters from freeing slaves altogether.Footnote 7 In Dutch Surinam, from the 1730s to final emancipation in 1863, slave owners needed to submit requests to concede freedom to a manumission court. According to the historian Brana-Shute, in any given year, from the 1760s to the 1820s, the number of slaves manumitted never exceeded the proportion of 0.8 per cent of the total slave population.Footnote 8

In Brazil, although achieving freedom remained difficult for as long as slavery existed, the state never took the initiative of forbidding owners to manumit their slaves. On the contrary, the masters’ exclusive prerogative to decide whether, when, or how to free their slaves constituted a major aspect of social control within Brazilian slavery; as a consequence, the seigneurial class resisted and resented every government attempt to create ways for slaves to obtain freedom irrespective of the masters’ will.Footnote 9 In 1871, a law that declared free the children born to slave women after that date and gave slaves the right to freedom by self-purchase, regardless of their masters’ consent, infuriated coffee planters but won approval in parliament after months of political turmoil.Footnote 10

In any case, the data gathered by historian Robert Slenes, based on the two national slave registrations, in 1872–1873 and 1886–1887, show that manumission rates varied enormously in different regions of the country. In the city of Rio de Janeiro, for example, access to freedom was significant: 36.1 per cent of slaves listed in the 1872–1873 slave registration had obtained freedom by 1886–1887. The situation in the capital contrasted sharply with areas dominated by coffee cultivation. Hence, 11 per cent of captives held in 1872–1873 had been manumitted in the province of São Paulo by 1886–1887; 7.8 per cent in the province of Rio de Janeiro; just 5.6 per cent in Minas Gerais.Footnote 11

The second observation derived from these numbers is that in Brazil, to a greater extent than in other slave societies in the Americas, slave emancipation occurred concomitantly with the continuity of slavery itself, leading to the figure, just mentioned, of about 74 per cent of people of African descent being free or freed in 1872. In this context, historians’ traditional focus on ways of obtaining freedom in nineteenth-century Brazil must be balanced by further attention to the experience of freedom for this ever-growing contingent of ex-slaves and their descendants. In addition to the widespread practice of illegal enslavement, there existed several legally sanctioned situations – such as conditional manumissions and revocation of freedoms – that often made the boundaries between slavery and freedom uncertain, thus constituting a structural feature of that society, conducive to strategies for the control of workers, slave and free, based on personal dependence and paternalist ideology.

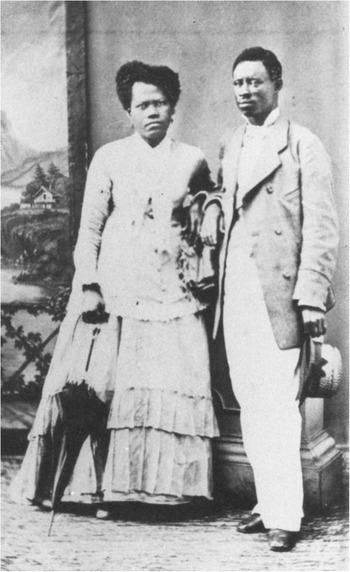

Figure 2 Portrait of a couple; carte de visite; photographer: Militão Augusto de Azevedo, São Paulo, c.1879. Museu Paulista, São Paulo. Used with permission.

Slavery and freedom in Brazilian historiography

Until recently, historians seemed to share a paradigm, so to speak, for the study of slavery in Brazil and perhaps in the Atlantic world in general. In the mid-1980s, Rebecca Scott described the frame of mind prevailing in the field, stressing that studies on the history of slavery had overcome the common association between subordination and passivity. In other words, historians had learned to consider slave initiatives within the system that oppressed them, and to explore the creation of alternative values and beliefs despite the burdens of economic exploitation and social and ideological domination.Footnote 12 It appeared possible to bring slave communities to life in historical narratives, largely because there was agreement regarding what constituted the politics of dominion in slave societies, and to approach the question of what slaves did with what was done to them – just to retread the battle cry of social historians in those glorious times.

The politics of dominion in slave societies centered upon three aspects: the slave market, with its transformations over time and impact upon slave communities; ideologies and practices with regard to manumission and the constitution of slave families;Footnote 13 and, last but not least, physical punishment, then seen not just as a reaffirmation of violence as the cornerstone of slave discipline, but as happening in the context of class struggle, somewhat limited by slaves’ pressures and concepts about fair treatment and tolerable punishment.Footnote 14 More recently, the effort to pursue slaves’ views of slavery in Brazil, where African-born captives comprised the majority of the slave labor force in most regions until past the mid-century, entailed seeking the forms of re-appropriation and recombination of cultural legacies in the context of New World slavery. People who arrived in Brazil through the slave trade “discovered” Africa in New World slavery, meaning that their common fate made them aware of the connections and shared assumptions pertaining to their otherwise unique ethnic legacies.Footnote 15

In a critical essay still to appear, Robert Slenes remarks that divergent perspectives now prevail among historians regarding the slave family and manumission.Footnote 16 On the one hand, authors such as Manolo Florentino and José Roberto Góes consider slavery in Brazil to have been characterized by significant social mobility: a considerable number of slaves achieved freedom consistently over time; freed people often had access to land, either as tenants or owners of a few acres, also becoming masters of slaves.Footnote 17 These openings for social mobility weakened horizontal solidarities among captives, making rivalries and competition among them rather common, therefore strengthening seigneurial domination. In other words, owners seemed more able to impose their rule on slave quarters divided ethnically and appreciative of the opportunities for the formation of family and kinship ties – resistance “pacified”, as Florentino and Góes would have it. Slenes deems such interpretation static and culturalizing, failing to account for historical change, although recognizing the oppressive nature of the slave system to a certain degree.

On the other hand, there are historians who emphasize social transformation and patterns of everyday conflicts as determining factors for the political views and strategies of both masters and slaves. Hebe Mattos, for example, argues that slaves’ and freed people's expectations concerning social mobility changed considerably over the course of the nineteenth century.Footnote 18 In the decades following Independence (the 1820s to 1850s), the expansion of coffee cultivation intensified the competition for land, making its acquisition increasingly difficult for free and freed people of color. Furthermore, because of the rise in prices after the cessation of the slave trade in 1850, poor people in general, including freed persons, had their access to slave property, a prerequisite for capital accumulation and social mobility in that society, significantly reduced.Footnote 19 As the century wore on, the concentration of slave property in fewer hands and the massive transfer of captives from the northern to the southern coffee-growing provinces deprived the institution of slavery of the broad social backing it had enjoyed in the first half of the nineteenth century.

In making social mobility the crux of their interpretations, these historical perspectives, however different, assume the existence of areas of uncertainty or blurring between slavery and freedom in nineteenth-century Brazil. Nonetheless, these indefinite boundaries are conceived of mainly as continuous or interrupted opportunities for upward social mobility. In other words, there is a shared lack of emphasis – more so for Florentino and Góes than for Mattos – on the conditions that rendered freedom precarious, and also on how such precariousness changed over time. To put it bluntly, the pressing insecurity of their condition shaped free and freed blacks’ expectations and daily strategies at least as much as their often protracted hopes for upward social mobility.

Citizenship rights

The Constitution of 1824 considered freedmen born in Brazil to be citizens. It did not mention African-born freed people, who were numerous because of the high percentage of Africans among slaves for as long as the slave trade continued. It was clear, however, that an African captive, when freed, remained a foreigner, thus eligible for citizenship only through naturalization. Perdigão Malheiro, in his influential study of the legal aspects of Brazilian slavery published in the 1860s, said that there existed no legislation to impede the naturalization of Africans, although the underlying assumption of the comment was that such a possibility would be unexpected or unwelcome.Footnote 20 Police documents pertaining to the city of Rio de Janeiro, from the 1830s to the 1860s, show that there was great hostility toward freed Africans, often suspected of luring slaves to run away, planning rebellions, and having an inclination toward vagrancy and crime.Footnote 21 The police often had them summarily deported to Africa, especially in the aftermath of slave rebellions such as the one in Bahia in 1835.Footnote 22

Regarding the political and civil rights of Brazilian freedmen, Perdigão Malheiro thought that their condition “in our society is highly restricted” because of “a generalized racial prejudice against the African race”.Footnote 23 In the electoral system established by the Constitution, with two principal stages of citizenship rights mainly on the basis of wealth, freedmen could vote in primary or local elections. They could vote for and be elected to the municipal council, but they were not allowed to participate in the following stage, the election of provincial deputies, general deputies, and senators. Since citizenship rights also served as criteria for the occupation of jobs in the state bureaucracy, a freedman could not be appointed a justice of the peace, ranked police officer, attorney, judge, diplomat, or bishop – they were even barred from serving as jurors in jury trials. They could be admitted to the National Guard, but not as officers.Footnote 24 As for civil rights, still following Perdigão Malheiro, manumission gave freed people the condition of persons, “who could exercise freely their rights and activities, according to the law, as could other citizens, form a family, acquire property” etc. (emphasis in the original). He compared the situation of freed persons to that of minors coming of age.Footnote 25

The 1832 code of criminal procedure gave freed Africans and slaves the same treatment concerning travel within the country: they had to have a passport, even when accompanied by their masters or protectors.Footnote 26 At local level, restrictions on freed Africans’ economic and social activities were commonplace. In Salvador, in the province of Bahia, a city ordinance issued in 1859 established a fine for slaves caught on the streets at night who did not carry the written permission of their masters; likewise, freed Africans would be fined in the amount of 3 mil-réis (worth at least three days work), or eight days in prison, if found on the streets at night without a note “from any Brazilian citizen”.Footnote 27 In other words, an African freed person could not move about the city freely at certain times without the protection of a citizen, someone willing to vouch for his or her conduct.

The example from Salvador comes from historian João Reis's recent book on the life of Domingos Sodré, an African slave, later freed and becoming the owner of slaves, who lived in the city in the years following the 1835 rebellion. Restrictions on the economic activities of freed Africans increased in the period. It seemed that local authorities intended to keep freed Africans under constant pressure, perhaps to convince at least some of them to cease living in Bahia, preferably assuming for themselves the cost of a return to their native continent. A law enacted in May 1835 almost went so far as asking freed Africans to leave, for it created an annual tax of 10 mil-réis that applied only to them if they wished to continue residing in Salvador. The same law prohibited them from acquiring any real estate, thus leaving slave property as their only option for investing personal savings. João Reis sums up the situation saying that, “respecting Africans, a tenuous line separated the condition of freed from that of slave”.Footnote 28

As for Brazilian freed people's political rights, a serious setback occurred in the 1880s. A new electoral law enacted in January 1881 abolished the different stages of political rights established in the Constitution of 1824. In theory, Brazilian freedmen could now vote and be elected to the same offices open to other citizens, without exception; in addition, all jobs in the state bureaucracy became a possibility for them. However, the new law raised income requirements significantly; even worse, it made mandatory that voters be able to read and write, a novelty well attuned to the Western liberal tenets of the times.Footnote 29 But such a law was enacted in a country where blacks attending school seemed a matter for the police to deal with. On 27 March 1835, the chief of police of the city of Rio sent a “reserved” letter to the justice of the peace of the parish of Santana asking him to investigate meetings taking place at a given house in the neighborhood, “allegedly a school for Mina blacks [people from West Africa] to learn how to read and write”. The police chief added that the Africans gathered everyday in the afternoon, therefore the justice of the peace had to prepare a “detailed” report on their activities “urgently”.Footnote 30

Given the year of this occurrence, 1835, the chief of police may have taken action on this gathering of Africans not because of the alleged purpose of their meetings – learning how to read and write – but because he suspected that they might be plotting an insurrection or something else surely more threatening than elementary school. Furthermore, since the Africans involved were identified as Mina blacks, it is probable that the police feared that they were engaged in Quranic lessons, an activity seen as dangerous because the authorities thought that the 1835 rebels in Salvador communicated in Arabic amongst themselves. There was no law prohibiting teaching slaves to read and write in Brazil; nonetheless, there can be no doubt of the total lack of interest of Brazilian masters in the literacy of their slaves, for security concerns or whatever other reason.

The census of 1872 registered no slaves at all attending school in the whole country. However, the census found that 1,401 captives knew how to read and write, not an impressive number given a slave population of more than one and a half million – that is, 0.08 per cent of slaves were literate.Footnote 31 In the city of Rio, where the situation regarding literacy seemed much better than in the rest of the country, 329 captives were able to read and write in a total slave population of more than 48,000 – that is, 0.7 per cent of captives were literate in the capital. Data about literacy in the 1872 census appeared appalling in general, for it became known that for every 100 inhabitants, 81.4 were illiterate; by excluding children under 5, too young to go to school, one comes to a figure of 77.4 illiterate per 100. The city of Rio was the only place where more than half the population could read and write – and just barely, 50.1 per cent.

Apparently shocked by the census results, politicians devoted much time and talk to the question of elementary schooling in the following years, but no meaningful action ensued. Instead, the literacy requirements established by the electoral law of 1881 curtailed decisively the citizenship rights of generations of people of African descent that had become or were about to become free at the time. The perverse combination of literacy requirements for voting rights and lack of elementary school for the poor continued for decades to come.Footnote 32

Conditional manumissions, revocation of freedoms

There were diverse ways to obtain freedom in Brazilian slavery: letters of manumission; freedoms conceded in last will and testaments and post-mortem inventories;Footnote 33 liberties granted at the baptismal font; and manumissions achieved by judicial means. Manumissions could be gratuitous or unconditional, in which case the freed person had no further obligations toward the ex-proprietor (other than gratitude and due respect); and onerous or conditional, which lumped together a variety of situations, ranging from the establishment of conditions such as continued service for a number of years – often seven – or until the death of the owner, to self-purchase, which could be done in instalments paid over the years. Self-purchase was different from other types of conditional manumission because the initiative belonged to the slave, or to a third party acting on her or his behalf.Footnote 34 A vast area of untapped research concerns the relation between the type of manumission obtained by a freed person and his or her degree of autonomy vis-à-vis the ex-master thereafter.

It seems that conditional freedoms associated with continued service constituted a sizable number of all manumissions in nineteenth-century Brazil. In his classic piece about the subject in Campinas, Peter Eisenberg computed letters of manumission for the period 1798 to 1888, and found that, despite variations over time, liberties granted upon the requirement of continued service for a time consistently represented about 50 per cent of cases. Self-purchase appeared in another 30 per cent of the letters.Footnote 35 In a more recent study, also about Campinas, Lizandra Ferraz analyzed manumissions in last will and testaments and post-mortem inventories, to discover that conditional freedoms comprised 30 per cent of the sample in the period 1836–1845, then reached 34 per cent in 1860–1871.Footnote 36 These studies suggest that there may be variations in the results obtained depending on the historical sources used: for example, in Campinas, conditional manumissions requiring continued service were more common in letters of freedom than in last will and testaments and post-mortem inventories. More important, though, for my purposes here, is that manumissions requiring a condition to be fulfilled by freed persons represented a considerable percentage of freedoms granted whatever the historical source analyzed, thus launching freed people on to murky terrain between slavery and freedom, to be shaped by a process of negotiation and conflict with their masters or patrons.

Klein and Luna collected the results of more than twenty studies on manumission in Brazil, about different periods and regions, organized them in tables that are very useful for comparative purposes, and there we find that, despite variations to be expected given the diversity of situations, conditional manumission was significant everywhere, at any time, ranging from about 20 per cent to 70 per cent of cases in the samples, but more typically representing around 30 or 40 per cent of manumissions.Footnote 37 As to what conditional manumission meant for freed people, whether it entailed a situation markedly different from slavery or not, little is yet known, with historical sources seemingly open to the most contradictory interpretations, perhaps because the situation remained very indeterminate for masters and slaves, patrons, and the freed persons themselves. For instance, legal controversies abounded on the condition of the child of a freed woman who had been granted a letter of manumission but had yet to fulfill the requirements there established. Did she remain a captive until serving fully the period of further labor demanded of her, in which case her child had been born in bondage? Or was it otherwise, with freed women in the same position as minors, awaiting full emancipation, but then giving birth to free children?Footnote 38

Manolo Florentino's study on manumission in the city of Rio from 1789 to 1871 shows that important changes occurred over time concerning the relative importance of each type of manumission. In periods in which freedom by self-purchase appeared to be more accessible, meaning that captives were having more economic opportunities and therefore saving more to gain liberty, the tendency was to see more people in general becoming freed, increasing likewise the presence of freed people in the total population of the capital. In other words, only freedom by self-purchase guaranteed periods of significant increase in the rate of manumissions, with other types of liberty merely sustaining the proportion of freed people in relation to the total population of the city.Footnote 39 It is also possible that freed persons granted conditional manumissions remained more vulnerable to re-enslavement, since slaves who succeeded in buying themselves out of bondage probably strengthened their position vis-à-vis former masters – maybe they enjoyed a higher degree of autonomy than people with lingering obligations. Also, freedom by self-purchase may have guaranteed more autonomy than voluntary, unconditional manumission, with the recipients of the latter having to show eternal, unabated gratitude to their benefactors.

Revoking freedoms by alleging ingratitude on the part of an ex-slave remained a master's right until the enactment of the Law of the Free Womb, in 1871. Until recently, students of Brazilian slavery thought that revocations of freedom were rare. Not any more. Keila Grinberg has been suggesting that historians, myself included, have misread, at least in part, the many slaves’ appeals for freedom existent in Brazilian archives. Studies using judicial records have focused upon slaves’ initiatives to file for freedom in court, their ability to find allies for their causes, the arguments mustered to forward their legal cases.Footnote 40 However correct this approach, it has missed evidence that often times in these lawsuits an ex-slave was seeking to defend a condition of freedom that he or she had obtained in the past, and had been enjoying when the legal case started – in other words, the freed person was actually struggling against an attempt to re-enslave him or her. According to Grinberg, in a sample of 402 lawsuits to decide the bondage or freedom of one or more persons pertaining to the Higher Court of Rio (Tribunal da Relação do Rio de Janeiro), 27 per cent consisted of appeals to re-enslave someone, or for someone to maintain freedom. As is obvious, in appeals for re-enslavement, the ex-master or his/her heir initiated the case, hoping to regain property rights over a given person; in appeals to maintain freedom, freed people took action to resist an ongoing attempt to return them to bondage. Grinberg's study hints that captives who had received conditional manumission were more likely to face the threat of revocation on the supposed grounds of ingratitude.Footnote 41

Grinberg's work details legal arguments put forward in appeals to maintain freedom and in attempts to revoke manumissions, and computes their results, seeking to evaluate freed people's chances of confirming their condition through these means, and comparing what she finds in the judicial cases with discussions conducted in law books and periodicals. Although the point is not developed in her work, it suggests the need to relate the different forms of manumission to the frequency and content of judicial cases motivated by attempts to re-enslave freed persons.

The following extract, dated 28 July 1870, tells the story of Augusta, a woman who sought legal protection for her liberty:

The black Augusta, a Brazilian, says that about eight years ago, the Lieutenant Colonel José Rodrigues Gonçalves Valle freed her by letter, with the condition to accompany him during his life.

Upon the Lieutenant Colonel's death on 8 November 1864 (see attached document), the Plaintiff left the house and separated her savings, as a free person, that she is, and in this state has remained ever since, without contestation from anyone. Recently, however, João Carlos Álvares Valle, who alleges to be in charge of the post-mortem inventory of the property of the deceased Lieutenant Colonel, has intended to consider the Plaintiff a slave pertaining to the inheritance, seeking to force her to pay him a daily sum, which is a violation against the freedom that the Plaintiff has legitimately acquired, and has possessed for more than five years.

And because the Plaintiff's letter of liberty, given by the deceased Lieutenant Colonel, has disappeared, the Plaintiff wants to justify her allegations with the depositions of persons who saw the mentioned letter, or know of its existence, in order to obtain a ruling in her favor.Footnote 42

Augusta's petition suggests that she might be having trouble with the heirs because she was not able to present written proof of the arrangements she had made with her ex-master. The fact that the freedom granted her had been pending on a condition may have weakened her position as well. But the judge deemed reliable the witnesses presented by Augusta and decided to confirm her freedom. She succeeded because she was able to enroll people willing to confirm her story, thus showing that the condition had been fulfilled, that the letter of manumission existed, and that the heirs had not questioned her condition for years, therefore tacitly recognizing that she had a right to freedom. Furthermore, the judge's ruling “maintaining her in possession of her freedom” (“manutenida na posse de sua liberdade”) provided her with a document, a valuable piece of paper to use thereafter in defense of her freedom.

Actually, it seems that often times freed people filed petitions to “maintain the possession” of their freedom to create a paper trail of their condition, as was emphatically asserted by the “pardo Matias”, who once avoided an arrest demanded by his alleged master waving a certified copy of a judge's ruling of this sort to police officials about to detain him.Footnote 43

Figure 3 Portrait of Glyceria da Conceição Ferreira; carte de visite; Carneiro & Gaspar Studio, Rio de Janeiro, c.1872. Arquivo Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. Used with permission.

Illegal enslavement

On 7 November 1831, as a consequence of a treaty signed with Great Britain associated with the formal recognition of independence, the Brazilian government enacted a law prohibiting the slave trade. Such law was systematically disrespected for the following two decades, a period during which about 750,000 Africans were smuggled into the country,Footnote 44 therefore making illegal enslavement a major source of slave labor for the rapid expansion of coffee in the south-eastern provinces. Notwithstanding its failure to abolish the slave trade, recent research has been exploring precisely the political and social consequences of such law, how non-compliance with it impacted relations between masters and slaves, and public policies regarding slave emancipation.

There were moments in which it appeared possible that the 1831 law could become decisive in slaves’ strategies for achieving freedom, threatening to bring to court the question of the illegality of much of the slave property existent in the country. According to historian Elciene Azevedo, the black abolitionist Luiz Gama attempted just that in the 1860s, a decade during which the British also kept the imperial government under pressure to resolve the question of the africanos livres – liberated Africans – who were those Africans apprehended in ships involved in the contraband trade, declared free and put under the protection of the Brazilian government, which in its turn exploited their services in public works and hired them out to private citizens. Luiz Gama rightly argued in judicial petitions – although to no avail – that the concept of africanos livres should encompass all Africans imported after the enactment of the law of 1831, and not just those recovered by British warships and given to the imperial government.Footnote 45 Beatriz Mamigonian concluded her detailed study of africanos livres reflecting on the question of how the experience of these few thousand Africans may have influenced the strategies and visions of slavery and freedom of others, hundreds of thousands, introduced by contraband and held illegally under bondage.Footnote 46

Mamigonian returned to the theme more recently, to ask the following question: “Considering that the illegality of the slave property originated in importations occurred after 1831 was uncontroversial, how did slave owners sustain their right to such property?”Footnote 47 The author examined resolutions by the Council of State, annals of proceedings and debates of the Senate, ministerial reports, and other official documents to surmise that politicians and public officials upheld the enslavement of Africans arrived after 1831 because such conduct was legitimated by custom – that is, planters had traditionally had their access to slave labor guaranteed, a seigneurial right so much recognized that the illegal enslavement of Africans seemed to count on the connivance of public authorities at all levels and to enjoy the active support of several sectors of the population. Nevertheless, there remained the problem of British pressure to broaden the meaning of africanos livres, with Her Majesty's diplomats in Rio eventually taking initiatives to denounce the open sale, sometimes in highly publicized auctions, of Africans whose ages made obvious their illegal importation.

In 1854, for example, British diplomats repeatedly complained of African slaves advertised for sale in local papers with the ages of nineteen or twenty, sometimes younger, rendering impossible their legal arrival before 1831. When the Minister of Justice asked the police chief for explanations, the answer he got was that the ages were incorrect because sellers had the habit of making their captives seem younger to obtain better prices for them; the chief explained that he had brought the Africans to his presence, had talked to them, had seen that they spoke Portuguese as ladinos (expected of Africans who had arrived years before), and ascertaining that they looked older than the ages advertised for them. But the police chief proceeded to remark that if he were supposed to

[…] inquire into these cases, of slaves announced for sale with 24, 25 years, just because they may have been imported after the law of 1831, then the same supposition could be made about other Africans, however their ages, 5, 10, 15 and older, because they too could have been imported after the aforementioned law, and it does not seem to me that our present circumstances make such investigations convenient.Footnote 48

As can be seen, there were serious risks involved in non-compliance with the law of 1831, risks that sometimes materialized in British initiatives and judicial appeals, forcing authorities to be vigilant to silence such attempts and deny them legal due process.

Concerning the slave owners approach to the law of 1831, it was surely cautious at the beginning, with importations dropping dramatically from almost 73,000 in 1829, when the trade was still legal, to little more than 6,000 in 1831Footnote 49 – according to the 1826 treaty between Brazil and Great Britain, the trade was supposed to have stopped by March 1830. However, the expansion of coffee, class solidarity, and the strengthening of the hold of conservative politicians in central government emboldened planters,Footnote 50 with the trade back to its full strength by 1837, when the daring was such that a proposal reached the Senate floor to revoke the law of 1831 and legalize all slave property acquired against its determinations.Footnote 51 The proposal to revoke the law met strident parliamentary opposition in both chambers and irked the British; although it passed in the Senate, the deputies buried it.Footnote 52 The illegal trade continued unabated in the following years, and there is a fascinating glimpse of what may have gone on in the minds of planters at the time in the excerpt below, taken from the last will and testament of Antônio Machado de Campos, from Campinas, province of São Paulo, 1837:

Due to ignorance and because other people told me that I could do it, I bought two Africans after the law that forbade these transactions, and because my only wish is to save my soul and in matters of conscience one has to proceed very cautiously, I ask the person in charge of my last will and testament to take the aforementioned Africans to the judge of the orphans, requiring that they be deposited with my heirs until they are educated, and they will be baptized, but not as slaves. Therefore I finish this will, and I want fulfilled what I establish here, except that if there is a law determining that the Africans now existent should be slaves, then the two about whom I made the declaration above must belong to my heirs as their slaves.Footnote 53

The passage bears witness to the class solidarity prevailing among slave owners, with planters encouraging each other to disrespect the law, all of them patriotically sharing the ideal of increasing their wealth through contraband and the illegal enslavement of Africans – incidentally, “to reduce a free person to slavery” was a crime specified in the 1830 criminal code. On the subject of class conscience, Antônio Machado performed equally well, for he showed that he was aware of parliamentary debates about the revocation of the law of 1831 and the legalization of slave property held illegally, thus the conditional form used in his will – “if there is a law determining that the Africans now existent should be slaves”. Although seigneurial expectations for the repealing of the 1831 law did not prevail, at least one deputy argued convincingly that the mere discussion of the subject in the parliament seemed to have helped to legitimate the contraband trade, contributing to increase the pace of importations.Footnote 54

The appalling rate of illegal enslavement that occurred after 1831 impacted the daily experience of freedom for people of African descent in general, since it caused insecurity and rendered freedom precarious. The connection between illegal enslavement and the precariousness of freedom is crucial, both to understanding the logic permeating public policies and to observing the strategies used by blacks and pardos, slave, free, and freed, to deal with it.Footnote 55

Slave owners’ interest not to abide by the law of 1831 necessarily meant increasing slackness in property requirements thereafter. For example, in the early 1830s, when attempts to curb the illegal trade were still in order, the police authorities in the city of Rio quickly realized that they needed to prevent the transportation of Africans to where they were in demand, that is, to the interior of the provinces of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Minas Gerais. Despite the fact that conductors of slaves for sale in the interior needed to have the captives’ passports ready for presentation to the authorities in controlling posts along the road, the issuing of these documents remained confusing. They could be obtained from different authorities, such as justices of the peace, police officials, and even from employees in ministerial offices, making it difficult to establish equal requisites for all cases; furthermore, the alleged owners of the slaves to be transported did not have to present documentation of the original transaction that brought them into the possession of the enslaved persons in the first place.Footnote 56

The absence of this requirement is telling, since it alone made it rather easy to claim ownership of recently arrived Africans, who after 1831 could no longer be introduced through the alfândega (customs), with its ensuing certificates and receipts associated with the collection of due taxes. With government revenue on slave property suddenly downsized to Lilliputian proportions, laxity regarding primary documents of ownership became a must, with authorities in Rio and elsewhere eager to have proprietors pay taxes on their slaves.Footnote 57 Hence, a law enacted 11 April 1842, establishing rules for slave registration and for the payment of annual and sale taxes on slave property, reassured owners saying that, “On the occasion of the first registration, nobody can be required to present the title through which [he or she] came into the possession of a slave.”Footnote 58

Rules and procedures to make it possible not to recognize illegally enslaved Africans and to give the appearance of legality to property originated in contraband had two consequences. First, it encouraged slave stealing, an activity that seems to have acquired epidemic proportions in the 1830s and 1840s, at least judging from the amount of time and effort the police dedicated to prevent it during the period.Footnote 59 Slave stealing necessarily involved establishing networks with the participation of a variety of individuals, beginning with the captives themselves, who often agreed, and sometimes asked, to be taken away.

In May 1837, the justice of the peace of the first district of Sacramento parish received the information that a tavern in the neighborhood served as a gathering place for the enticement of slaves to run away.Footnote 60 As was usually the case in such matters, a slave made the first contact with his or her fellows and attracted them to the tavern. In this case, his name was Matheus, an African from Congo and a mason. Interrogated by the judge, one of the blacks to be carried away, Manoel Monjolo, said that he wanted “to embark to get rid of the bad master he had”; in addition, he explained that Matheus had approached him saying that Joaquim José Ribeiro, a Portuguese man who worked in the tavern, could arrange for him to be sent away. The negotiations continued for a while, with Manoel Monjolo perhaps seeking to be assured that he would be moving to a more advantageous situation within bondage; he said that he had had meals with Matheus in the tavern “several times”, without ever paying for them. The police caught Manoel Monjolo and Joaquim José Ribeiro as they walked to Prainha, a beachfront location, supposedly the departure point for the stolen slave.

Had the journey proceeded, Manoel Monjolo would have joined other slaves and been conducted, maybe by another Portuguese man, to the interior of the province of Minas Gerais or São Paulo, for example. There he would have been sold to a coffee planter, probably under a new name, João Monjolo, for instance; the master would have included him on the list of slaves pertaining to his household, registered him, and paid the annual slave fee. More importantly, the alleged master would have counted on never being asked to document how he had originally obtained the captive.Footnote 61 As this case shows, the business of acquiring smuggled Africans became inseparable from having a constant influx of stolen ladino slaves as well, therefore occasionally giving captives the opportunity to take the initiative to change masters, hoping to improve their lot within slavery.

The second consequence of looseness respecting proof of slave property was that illegal enslavement became a greater threat to free and freed people of color in general – both African- and Brazilian-born. Although it is not possible to know the frequency of such events, they pop up sufficiently often in police correspondence, prison books, and trial records to suggest that potential victims had to deal with the problem, calculating their moves and remaining vigilant. Judy Bieber published a path-breaking study on the subject some years ago, relating cases of the kidnapping and sale of crioulos (Brazilian-born blacks), free and freed, quite often children, in the province of Minas Gerais.Footnote 62 On 1 September 1854, the Chamber of Deputies discussed a proposed law to control the internal slave trade, which had been increasing since the abolition of the African trade in 1850. João Maurício Wanderley, a deputy from Bahia, spoke extensively on the consequences of the internal trade for the northern provinces; slave owners there, especially those of modest means, lured by the high prices paid for slaves in the coffee-growing provinces, had been selling their labor force, condemning themselves to poverty. Furthermore, demand for labor was so high that a new “speculation” had developed – namely, reducing free people to slavery. The kidnapping and sale of free and freed black and pardo children to slave dealers had become commonplace; sometimes guardians of children of color sold them to slavery.Footnote 63

Criminal and civil records render vivid tales of the illegal enslavement of Brazilian-born slaves. In April, 1865, a black man, José, supposedly a slave belonging to Fuão Goulart, gave a detailed account of his plight when arrested for the homicide of Silva Pereira, his alleged master's son-in-law.Footnote 64 Although one can never be sure that José presented events as they really happened, or even as they seemed to have happened from his point of view, his narration was not contradicted by other witnesses in any important aspect, thus allowing us to take the tale as plausible – that is, truthful or not in its particular details, it provides valuable information about the experience of free and freed people of African descent in the period.Footnote 65

José, who was a shoemaker, had been born in Pau d'Alho, in the north-eastern province of Pernambuco. He was thirty-seven years old, single, then living in the city of Rio; he said that he resided on Catumby Street, but did not know the number. He confessed to having stabbed the victim out of despair caused by the harsh physical punishment imposed by his master. Answering questions asked by a police officer, José declared that:

He, the respondent, is free by birth; his mother is alive in Pau d'Alho, and her name is Joanna Maria da Conceição; besides her mother, he also has an aunt in Recife, Silvéria Maria da Conceição, who lives on Direita Street […], and the Lieutenant Colonel of the National Guard Antônio Laurianno Lopes Coutinho, who also lives in Recife, on Queimados Street, served as godfather at his baptism. [He said] [t]hat he came to this capital engaged by the Portuguese Manoel Teixeira de Araújo, as his servant; but this man had to go to a hospital and left him with Bernardo José Pinto, who lives in this city on Rosário Street, from where he the respondent was taken to Cantagalo [a county in the province of Rio], lured by promises to earn more money there working at his profession; but there arriving he learned that he had been enslaved, and not being able to suffer the punishments inflicted upon him, he tried to commit suicide by cutting his own throat with a razor. From Cantagalo he was sold to Fuão Goulart, who now lives on Catumby Street, there receiving the same punishments he had been suffering in Cantagalo; yesterday, as he left the shop where he worked to take a knife to sharpen, without the intention of killing anybody, it happened that he met Pereira on Cano Street; Pereira then grabbed him […] to conduct him to Goulart's house, and it was on this occasion that the respondent, having received several blows given by Pereira with his umbrella, stabbed him, which he did not intend to do, and Pereira contributed for this outcome because he inspired terror in the respondent, threatening that he would be put in shackles and receive beatings; that he regrets what happened to Pereira, and wished he had done it to himself […].

José probably belonged to a family whose members had recently obtained freedom – perhaps the very first generation of a family of freed people. His mother carried the names of “Maria” and “Conceição”, alluding to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and very common among freed women;Footnote 66 also, she managed to have her son baptized by a person of a higher social status, a “Lieutenant Colonel of the National Guard”, a strategy to bring recognition to her child's status as free or freed. Nonetheless, poverty and destitution, and perhaps the hope of achieving a better economic situation, made José take his chances in the nation's capital, therefore falling prey to criminal gangs willing to enslave free people and sell them to coffee planters. The detailed information provided about relatives in Pernambuco suggests that he had a safety net in his native province, with his mother having devised spiritual and social strategies to keep him safe from birth.

It is curious that José was a native of the parish of Pau d'Alho and said that his mother lived there. The parish of Pau d'Alho was at the center of a major popular revolt against a civil registration law in 1852. According to contemporary accounts of the revolt, people who participated in it alleged that mandatory civil registration was actually a strategy to enslave free people of African descent because “the English no longer allowed the coming of new Africans”.Footnote 67 We do not know if José lived with his mother in Pau d'Alho during the 1852 events. In any case, however truthful his narration in its details, it seems clear that he could articulate meaningful aspects of the precariousness of freedom in nineteenth-century Brazil.

I will indulge in one last story on the same subject, an almost rocambolesque one in the way it brings together successive episodes of illegal enslavement.Footnote 68 Joaquim de Azevedo Ramos initiated a petition on behalf of the pardo Odorico in 1862, alleging that he was his father and seeking to free him from a bondage he deemed illegal. Ramos said that by virtue of “the weakness of the flesh” he had had relations with the black woman Felismina, “who was free, but had been sold to the deceased father of the notary public Perdigão as a captive with the name of Thereza, and she died in 1842”.

Three witnesses offered detailed depositions to support the plaintiff's allegations. As stated by Leocádia Maria da Conceição, a seamstress, forty-five years old, and a freed woman who had worked side by side with Felismina in bondage, Perdigão and his family recognized Felismina's condition as free; nonetheless, they had her son, Odorico, baptized as a slave. Ana Rangel de Macedo, a school principal, seventy-two years old, and daughter of the notary public Perdigão, gave her account of the illegal enslavement of both mother and son, Felismina and Odorico. When she was seven, Felismina had been sold to her father by a man named José Bento, from Valença, a coffee county in the province of Rio, and given the name of Thereza. However, one day, as the supposed Thereza walked on the street with another slave woman pertaining to the household, a black woman who passed by recognized her as Felismina, born in Valença as a free girl and her godchild. The Perdigão family believed in the story and considered Felismina free thereafter. Later her sister, Dona Mariana, brought Felismina to live with her. Felismina gave birth to Odorico during this period; thus it seems that Dona Mariana had him baptized as slave, although her sister does not go so far as to say that. The third witness, Miguel Geraldo da Silva, a typesetter, thirty-four years old, confirms the whole story, and suggests that the family considered Odorico free because the young man, unlike slaves, went about the city wearing shoes.

In spite of the witnesses’ declarations that the Perdigão family deemed Odorico a free person, he was sold to Leopoldino dos Santos Pereira, who sold him to José Antônio Teixeira, who died, but whose widow intended to sell him again, finally prompting legal action by his father, Joaquim de Azevedo Ramos. Asked to present documentary evidence that Felismina had been a freed person, therefore proving that Odorico had been born free, Ramos argued that he took the trouble of filing the petition just because he did not have a paper trail to sustain his allegations. Since Felismina had been born free, and not freed after birth, he did not have a letter of manumission or another type of document to support his story. Here, again, as in the case of the black Augusta, seen above, part of the motivation to go to court consisted of creating a paper trail to safeguard the right to freedom. Paradoxically, Felismina's freedom seemed harder to prove than Augusta's because she had never been a slave. Augusta gathered witnesses to show that a letter of manumission had existed and disappeared. Felismina's ex-lover had to resort to witnesses to reconstruct her story from scratch, a mission made more difficult by the sheer fact that illegal enslavement entailed erasing or muddling the evidence of the original act of reducing someone to bondage.Footnote 69

Suspected of being fugitive slaves

During the long period during which he held the job of chief of police in Rio, from 1833 to 1844, Eusébio de Queiróz organized the routine procedures of the institution according to the tenet that “since it is not easy to obtain proof of slavery, when a black insists that he is free”, it seemed “more reasonable, in the case of blacks, to presume their bondage, until they present a certificate of baptism or a letter of liberty to prove otherwise”.Footnote 70 It is noteworthy that the policy of deeming a slave any person suspected of being one took root while the contraband trade brought more than 750,000 Africans to the country in the 1830s and 1840s. Eusébio de Queiróz's doctrine provided a rationale, so to speak, for overlooking procedures that would have made it difficult not to recognize the illegal enslavement of Africans. Moreover, it transferred to Africans and their descendents the burden of proving their liberty, at a time when masters would have problems if pressed hard on the question of how they had originally acquired much of their slave property.

The consequences of such police conduct were durable for people of African descent, since their detention on the allegation that they were suspected of being fugitive slaves remained common for as long as slavery existed in Brazil. Not surprisingly, the police appeared particularly prone to making mistakes in this matter, not least because, as mentioned before, three out of every four blacks and pardos were free or freed according to the census of 1872. In the city of Rio, the 1872 census computed a population of 274,972, of which 226,033 were free people (82.2 per cent), and 48,939 slaves (17.7 per cent). As regards the racial composition of the free population in relation to the total population, 55.2 per cent were considered white, a high percentage due, in part, to the strong presence of Portuguese immigrants in the capital (more than 55,000), 10.3 per cent black, 16.3 per cent pardos, 0.33 per cent caboclos (mixed with Indians); among the remaining 17.7 per cent slave population, 77.3 per cent were black, 22.6 per cent pardos.Footnote 71 On the aggregate – that is, slave and free combined – the population of African descent in Rio represented 44.4 per cent of the total. Considering only the population of African descent, 59.9 per cent was free, 40 per cent slave; in other words, for every five people of color residing in the capital in 1872, three were free, two slaves.

Let us turn briefly to the Livros da Casa de Detenção da Corte, that is, the books that registered the entry to the House of Detention of people arrested daily in the city of Rio in the 1860s and 1870s.Footnote 72 Despite several gaps in the available data, the House of Detention books convey a wealth of information on each person detained – that is, name, age, nationality, place of birth, parents’ names, reason for arrest, marital status, address, occupation, height, color, clothes worn on occasion of detention, date of entry, date of release, name of master (for slaves), social condition (slave, free, freed), authority who ordered the arrest. There were different books for slave and free people. The database contains 8,445 entries: 2,697 in books pertaining to slaves (31.9 per cent), 5,748 in books for free detainees (68 per cent).

Focusing on slave entries reveals that throughout the period the main function of the police with regard to the institution of slavery consisted of assisting masters in disciplining their captives. Thus 61 per cent of slave arrests may be described as actions to help masters maintain control of their bonded labor force – for instance, detentions made on a master's request, capture of supposed runaways, arrests associated with slaves being out on the streets after curfew without a master's permission; 29.8 per cent of the detentions resulted from slaves being accused of committing a variety of felonies and misdemeanors; in 6.1 per cent of the cases the slaves took the initiative of seeking the police – for example, to complain of mistreatment or to file a petition for freedom; 3.1 per cent of the entries do not specify a motive for the detention.

Searching the database for entries associated with being a “fugitive” slave, or “suspected of being a fugitive” slave, we come to a total of 1,097 such detentions: 447 for “fugitive”, 650 for “suspected of being a fugitive”. Although 70 per cent of entries for these motives appeared in books dedicated to slaves, it is perhaps surprising to find nearly 30 per cent of them annotated in books pertaining to free people. However difficult to be sure about these matters, it seems that there were situations in which the police tended to take information as presented to them; therefore, if those detained for allegedly being runaway slaves declared themselves to be slaves and to have run away, they would enter a book for the registry of slaves as “fugitives”. In other words, the police appeared inclined to believe a person who admitted to being a slave, despite the fact that the police records carry several examples of free people who alleged themselves to be captives to avoid an immediate danger of forced recruitment for the army or the navy.Footnote 73 In addition, there were several cases in which the detainee would admit to being a slave, but deny the accusation that he or she had run away. Finally, there appeared entries in which the police doubted it all: a person was seized on suspicion of being a slave and of having run away; not giving credence to the suspect, but having to deal with his or her assertion of freedom, the police could register the case in a book pertaining to free people, creating a logical contradiction, since a free person could not be seized for being a “fugitive” slave. Alternatively, from a social logic specific to slave society, a slave could not be detained for being a “vagrant”, since the condition of slave linked someone immediately to labor for a given master.Footnote 74

Thus the 650 detentions given the justification of “suspected of being a fugitive” are of special interest to us because police conduct in this regard had an impact on the lives of free and freed people of African descent. The search yields 344 results in books for the registration of slaves (53 per cent), 306 in books for free people (an appalling 47 per cent). Nonetheless, results for the 1860s differ significantly from those of the 1870s. When 11 entries with illegible or unreliable dates are excluded, there appear 366 results for “suspected of being a fugitive” in the 1860s, distributed thus: 77.8 per cent in books for slaves, 22.1 per cent in those for free people. For the 1870s, there are 273 entries: 20.1 per cent in books for slaves, nearly 80 per cent in those for free people. In other words, the registration of arrests for “suspected of being a fugitive” largely moved from books dedicated to slaves in the 1860s to ones pertaining to free people in the 1870s.

Why did this change happen in the pattern of registry? Until the 1860s, the notion that a person taken to be a fugitive slave remained a slave unless proven otherwise continued to prevail. In the 1870s, no doubt as a consequence of the gradual emancipation law of 28 September 1871, the tendency became to consider free a person whose bondage could not be ascertained. After the 1871 law, only the certificate of slave registration (matrícula) served as the legal means for claiming slave property, or proving someone's condition as a slave. Hence, despite their profiling on the streets for “suspicion of being a fugitive”, it is probable that the police began to enter in books for free people the cases of detainees of African descent who asserted their freedom. In addition, these inconsistencies in the House of Detention books suggest again the frequency of social situations in which the frontiers between slavery and freedom remained blurred in nineteenth-century Brazil.

On the one hand, the doctrine of chief of police Eusébio de Queiróz helped to strengthen slavery and incorporate into it a massive number of Africans smuggled into the country in the 1830s and 1840s, as well as their increasing number of descendants, also illegally held in bondage for decades to come. As a consequence, generations of free and freed people of color had their experience of freedom largely structured by these circumstances, having to learn to deal with situations which could bring them under the threat of being reduced to slavery. On the other hand, in a society in which more than 70 per cent of blacks and pardos were free in the early 1870s, the 1871 law allowed many slaves to turn upside down the crux of Eusébio de Queiróz's doctrine: if the uncertain frontiers between slavery and freedom reduced opportunities for free and freed people of African descent, they also gave slaves the chance of seeking to pass as free, mingling and hiding among thousands of free and freed blacks and pardos living in the capital and elsewhere, challenging alleged owners, police officers, and judicial authorities to find their matrícula.Footnote 75

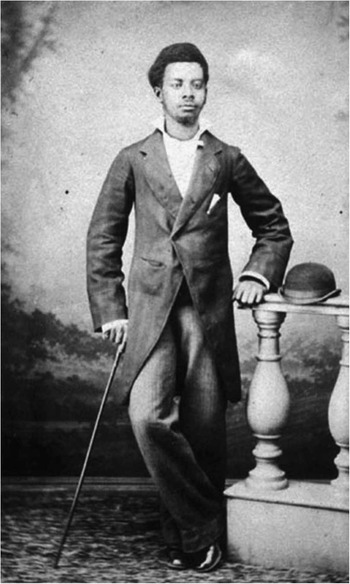

Figure 4 Portrait of a man; carte de visite; photographer: Militão Augusto de Azevedo, 1870s. Museu Paulista, São Paulo. Used with permission.

Structural precariousness and historical process

Seen from a distance, the abolition of the slave trade and of slavery proper were perhaps the most impressive nineteenth-century historical achievements of western European countries and their former colonies in the Americas. By the end of the century, nationalist deliriums, scientific delusions, and imperialist predation, on the part of several European countries, rested on representations about the progress of freedom and civilization that the suppression of slavery and other forms of compulsory labor epitomized. The end of slavery appeared as a prerequisite for industrial and technological progress, the expansion of markets, the improvement of financial institutions, the voluntary migration of workers, the acquisition of civil and political rights, and urbanization.

Nonetheless, such a panoramic perspective elides the indeterminate and fragmentary character of much of the history of slavery in the nineteenth century, particularly with regard to the strengthening of the institution in ways that rendered even more tragic the experience of the African diaspora. At the end of the eighteenth century, slavery remained strong in the British and French sugar-producing colonies. The Haitian Revolution interrupted the prosperity of the main French sugar colony; successive abolitionist waves and political turmoil ended British involvement in the slave trade and, subsequently, in the 1830s, brought slavery to an end in its colonies. The same historical process that consolidated the pre-eminence of Great Britain in world markets and international relations caused both the abolition of slavery in British colonies and the expansion of it in other areas of the Americas. In the following decades, as the cotton industry grew, the US South deepened its commitment to slavery; in 1830, Cuba had become the leading world producer of sugar, while its slave population of 85,900 people, in 1792, reached 286,900 in 1827, and 436,500 in 1841.Footnote 76

Due to low birth rates among the slave population, the expansion of coffee in Brazil in the second quarter of the nineteenth century depended heavily on the importation of enslaved Africans. Actually, demand for bonded Africans had been increasing since the 1790s as a consequence of markets made available after the collapse of sugar production in Haiti. In the 1820s, coffee remained the third item in the country's exports, after sugar and cotton.Footnote 77 In other words, the restructuring of slavery in Brazil, following the demise of gold mining, preceded the growth of coffee in the provinces of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

Current estimates for the number of Africans taken to Brazil during the whole period of the slave trade, from the mid-1500s to the early 1850s, stand at more than 4.8 million. In the first quarter of the nineteenth century (1801–1825), 1,012,762 Africans disembarked in the country; in the second quarter (1826–1850), there were 1,041,964, plus 6,800 after the 1850 law that effectively abolished the trade. These figures show that 42 per cent of the total number of Africans transplanted to Brazil during three centuries of the slave trade arrived there in the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 78 Most Africans introduced in the second quarter of the century ended up in coffee-growing south-eastern provinces; furthermore, a vast majority of them, approximately 750,000, came in contempt of the international treaties and national legislation that had prohibited the African trade.

As I have argued in this article, the core of the concept of the structural precariousness of freedom in nineteenth-century Brazil rests upon the idea that there prevailed, in the longue durée, modes and imperatives of social interaction that often made the boundaries of slavery and freedom uncertain. However important this feature of Brazilian slavery may have been in previous times, it acquired a new weight after 1831, when dealing, and eventually condoning, massive illegal enslavement gradually became an organizing principle of state formation and institutional building in the country. By the end of the 1830s, political groups that would soon coalesce in what became known as the conservative party, or saquaremas, held a firm grip on ideological views and political power,Footnote 79 henceforth directing public policies to defend the monarchical regime, the expansion of latifundia, and the institution of slavery – which increasingly meant procrastinating about the abolition of the slave trade and protecting the interests of those who held slave property illegally. With respect to the experience of freedom of people of African descent, they had to learn to cope with the consequences of the politics of precariousness in public policies and institutions, which shaped, for example, their routine interactions with the police, county officials, local judges and, last but not least, slave dealers and slave owners, for whom illegal enslavement seemed to have become a customary right.

The abolition of the slave trade after the enactment of a new law, in 1850, led to a period of political stability, with liberal and conservative political currents in agreement as regards basic ideological tenets and temporarily relieved from British pressure respecting the problem of slavery. In addition, the cessation of African arrivals quelled fears that a growing demographic imbalance might render more dangerous the rebellious disposition of slaves, whose actions by the end of the 1840s reminded masters and authorities of the situation they had confronted in the mid-1830s.Footnote 80 Nevertheless, as the abundance of labor since the large-scale importation of Africans in the late 1840s wore out, especially after a devastating cholera epidemic in 1855–1856, the experience of precariousness within slavery increased by virtue of a growing internal slave trade.Footnote 81 As a massive number of slaves began to be forcibly moved from the north-eastern provinces – where slave communities with a majority of Brazilian-born captives were more common – to coffee plantations in the provinces of Rio and São Paulo, concerns about slave resistance resurfaced, this time in the form of crimes committed by bonded people against masters, overseers, and their families.Footnote 82

The 1860s brought with it the recrudescence of British pressure, now focused upon the question of africanos livres – “liberated Africans”. W.D. Christie, Her Majesty's Minister in Brazil, argued vigorously that the definition of africanos livres should encompass all Africans introduced into the country in disrespect of the 1831 law, not just those Africans actually recovered during actions to repress the clandestine trade.Footnote 83 If such a thesis took hold, the recognition of the illegality of much of the existent slave property would follow. Not incidentally, perhaps, there appeared at the time judicial petitions for freedom defending the right to liberty of Africans imported after 1831.Footnote 84 The struggle for freedom that began to surface, in the context of mounting international isolation in the aftermath of the American Civil War, led to the first governmental and legislative moves toward gradual emancipation, resulting in the 1871 law.

The 1871 law seemed ambivalent. On the one hand, legislators sought to settle the question of slave property rights by establishing mandatory slave registration, thus creating an official document to legitimate slave ownership. On the other hand, government and judicial intervention on the question of manumission – with the law granting freedom to children of slave mothers born thereafter and opening paths to liberty irrespective of the masters’ consent – empowered slaves and their allies to struggle for freedom by resorting to the legal apparatus made available by the imperial government itself.

During the 1870s, patterns of slave arrests in the city of Rio show that the main rationale for police intervention continued to be that of assisting masters in disciplining their captives. In spite of that, slaves went more often to the police to confront the injustices of life in bondage, and appeals for freedom became more common in judicial courts.Footnote 85 Gradually, the customary situations of uncertainty between slavery and freedom began to offer opportunities for slaves to challenge masters’ control; for instance, their attempts to pass for free or freed people after 1871 required owners to present a certificate of slave registration to undo.

Although the 1880s started with growing expectations concerning slave emancipation, with the abolitionist movement spinning out of the parliament on to the streets of the capital, planters and their representatives resisted the demise of slavery with incredible tenacity. Planters would achieve a new legal compromise in 1885, which would not last long, but proved sufficient to guarantee to Brazil the dubious honor of having been the last country in the western hemisphere to abolish African slavery, in 1888.Footnote 86

The slaves who achieved manumission in growing numbers faced social and political redefinitions of the precariousness of freedom. They had been excluded from any aspiration to political rights as a consequence of the literacy requirements established in the 1881 electoral law, remained without access to elementary education for decades to come, and were not allowed to create mutual aid societies based on racial or ethnic identities.Footnote 87 In addition to these hurdles, people of African descent faced prejudices associated with scientific racism, which emboldened European imperialism and influenced ideologies and public policies in Brazil. The emergence of new labor ideologies changed the scope of the concept of vagrancy, tending to value wage labor, rejecting other options for earning a living and subjecting the urban poor to renewed forms of police profiling, with blacks and pardos being specially targeted.