1. Introduction

Positive psychotic-like symptoms, such as perceptual abnormalities and delusional ideas, are rather common and usually transient in the general population. By definition, these psychotic-like symptoms are subclinical, as in that they do not reach the psychotic threshold, and differ from the positive symptoms of a frank psychotic disorder quantitatively. However, psychotic-like symptoms may be a developmental expression of proneness to psychosis, which due to environmental adversity and other risk factors interacting with a genetic risk can become more persistent and lead to a clinically relevant disorder [Reference van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul and Krabbendam1]. For that reason, psychotic-like symptoms can be referred to as “positive psychosis risk symptoms”, which term is used hereinafter in this paper. As well as psychotic disorders [Reference Fusar-Poli, Borgwardt, Bechdolf, Addington, Riecher-Rössler and Schultze-Lutter2], positive psychosis risk symptoms may indicate a vulnerability to a wider spectrum of psychopathology [Reference Linscott and van Os3, Reference Kaymaz, Drukker, Lieb, Wittchen, Werbeloff and Weiser4]. Positive psychosis risk symptoms co-occur with a varied form of psychopathology and are not confined to any one psychiatric disorder. In addition, those reporting positive psychosis risk symptoms more often suffer from multiple disorders, and concurrent positive symptoms are associated with disorder severity, distress, and poorer prognosis [Reference Fusar-Poli, Borgwardt, Bechdolf, Addington, Riecher-Rössler and Schultze-Lutter2, Reference Hanssen, Peeters, Krabbendam, Radstake, Verdoux and van Os5–Reference Wigman, van Nierop, Vollebergh, Lieb, Beesdo-Baum and Wittchen7]. In the general population positive psychosis risk symptoms are associated with help-seeking and unmet need for care [Reference Armando, Nelson, Yung, Saba, Monducci and Dario8–Reference van der Steen, Myin-Germeys, van Nierop, Ten Have, de Graaf and van Dorsselaer12] and later psychiatric hospital treatments for severe mental disorders [Reference Werbeloff, Drukker, Dohrenwend, Levav, Yoffe and van Os13]. A recent review reported that in the general population, people with positive psychosis risk symptoms were twice as likely to report mental health service use compared to those without these symptoms, but service use was almost always assessed retrospectively and only by self-report [Reference Bhavsar, McGuire, MacCabe, Oliver and Fusar-Poli14].

In addition to positive psychosis risk symptoms, other psychosis risk symptoms include negative, disorganization, and general risk symptoms. Positive symptoms [Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Schmidt, Schimmelmann, Maric and Salokangas15] as well as negative symptoms [Reference Addington and Heinssen16] are associated with heightened risk for psychotic disorders. As to other outcomes besides psychotic disorder, negative and disorganization symptoms predict poor functioning during follow-up among at-risk individuals [Reference Cotter, Drake, Bucci, Firth, Edge and Yung17]. In one study, non-specific subjective anomalies in thinking and attention were more relevant to help-seeking and need-for-care than positive symptoms [Reference Brett, Peters and McGuire18].

Adolescents referred to psychiatric care for the first time have heterogeneous service needs over time and it is not clear how psychosis risk symptoms are associated with help-seeking behavior in adolescent psychiatric populations. The current study aims to investigate whether psychosis risk symptoms – as assessed with the Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ) – predict further patterns of treatment of adolescent non-psychotic patients. It was hypothesized that co-occurring psychosis risk symptoms at entry would be associated with prolonged subsequent mental health service use, making the PQ a potentially useful tool for screening for not just the risk for psychosis but also the risk for long-term service use. We also wanted to investigate whether distinct factors of psychosis risk symptoms correlate with service use differently. As adolescents with long-term need for help form a group warranting special attention, identifying factors associated with persistent service use may help to develop early prevention and intervention strategies.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and study protocol

We utilized the sample of the Helsinki Prodromal Study, a prospective study investigating psychosis risk [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen19]. All new patients aged 15–18 years entering adolescent psychiatric inpatient or outpatient clinic or ward in Helsinki, Finland were invited to participate in the study during years 2003–2004 and 2007–2008, the enrolment phase constituting a three year period. The adolescents were asked to fill out the PQ [Reference Loewy, Bearden, Johnson, Raine and Cannon20] on their first or second visit to the unit. 819 questionnaires were returned, totaling up to 75% of the eligible participants in psychiatric treatment. The patients who returned the PQ form did not differ from the other patients with regards to age (t(1611.2)=–0.304, p =.761) or gender (X2 = 1.920, df = 1, p =.166).

Adolescents who were diagnosed with a psychotic disorder at the time of or before the administration of the PQ (n = 27) or those who forbid the use of follow-up register data (n = 61) were excluded from the analyses. The PQ factor solution was made with these 731 adolescents. Finally we excluded 16 participants who according to the psychiatric register were diagnosed with psychotic disorders at baseline (ICD-10 codes F20, F22–F29, F30.2, F31.2, F31.5, F32.3, or F33.3), resulting in a final sample of 715 adolescents. The mean age of the final sample was 16.5 years and 489 (68.4%) were female. 27 participants (3.8%) completed the PQ in a psychiatric hospital and the rest were outpatients.

The review boards of the National Institute for Health and Welfare and the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa reviewed and approved the study procedure, the PQ being part of the standard treatment of the adolescents entering psychiatric units.

2.2. Prodromal questionnaire

Psychosis risk symptoms were assessed using the Finnish version of the PQ, a 92-item self-report survey assessing psychosis risk symptoms with a Yes/No response format [Reference Loewy, Bearden, Johnson, Raine and Cannon20, Reference Loewy, Therman, Manninen, Huttunen and Cannon21]. For use in later regression modeling, we extracted maximum a posteriori factor scores from two confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models: 1) the four a priori subfactors (positive, negative, disorganized, and general symptoms), and 2) the full PQ as a single dimension. These item factor analyses used the WLSMV algorithm, and took the dichotomous nature of the items into account. Factor model fit was quantified with the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and explained common variance (ECV), and was adequate both for the single-dimensional (RMSEA 0.042, CFI 0.87, ECV 36%) and the four-dimensional models (RMSEA 0.040, CFI 0.88, ECV 40%). Item factor loadings and thresholds are presented in Supplementary Table 1 and subfactor correlations in Supplementary Table 2.

2.3. Psychiatric register data

Baseline diagnoses of the adolescents were acquired from the Finnish hospital discharge database, a part of the Care Registration for Health Care (HILMO), with diagnoses between 30 days before and 30 days after the date of the PQ defined here as the baseline diagnosis. Psychiatric baseline diagnoses were grouped as non-psychotic mood disorders (ICD-10 codes F3X); anxiety disorders (F4X); eating disorders (F5X); substance use disorders (F1X); intentional self-harm (X69-X84, Y87, Y87.0, Z91.5, or Z72.8); disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence (F6X‒F9X, excluding F60.X and F99); and other psychiatric disorders (other F class diagnoses), to be used as covariates in the regression models predicting service use. A person could have a baseline diagnosis from several of these categories.

Follow-up data on the use of psychiatric services was available until the end of the year 2015 including psychiatric treatment in any public outpatient or inpatient clinic or ward. As the last participants were enrolled in year 2008, a seven-year follow up was available for them. The same length of follow-up was used for all participants, constituting data for the subsequent seven years after the completion of the PQ for each adolescent. The first follow-up year for each participant was 365 days starting the day after the completion of the PQ, the second year 365 days after that and so on. For each follow-up year, service use was coded as a dichotomous indicator (0=no treatment during the year, 1=treatment during the year). Based on the 7 repeated measurements, we formed three groups as follows: Brief contact: no service use after the first two years; Persistent contact: service use on five or more years during the seven-year follow up; and Intermittent contact: adolescents who did not fall into either one of the other categories.

2.4. Data analyses

Factor analyses were conducted with Mplus 8.0 [Reference Muthén and Muthén22] and other analyses with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25. Multinomial logistic regressions were conducted to test which variables predicted long-term service use, using the Brief contact group as the reference group. First, we tested which background and clinical variables were the individually significant predictors at a p <.05 level (gender, age, inpatient status, baseline diagnosis categories, multimorbidity, and the PQ symptom factor scores).

To test whether psychosis risk symptoms would predict psychiatric service use beyond diagnostic information, the significant background predictors were included in the final regression models in addition to the PQ factors. The predictiveness of self-reported psychosis risk symptoms was investigated in five separate models (one for each of the four PQ subfactors and the overall factor) because they were very highly correlated with each other, and multicollinearity concerns precluded their use in the same model.

Odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to estimate the effects; for continuous variables (PQ factors) OR values are given per standard deviation unit change.

3. Results

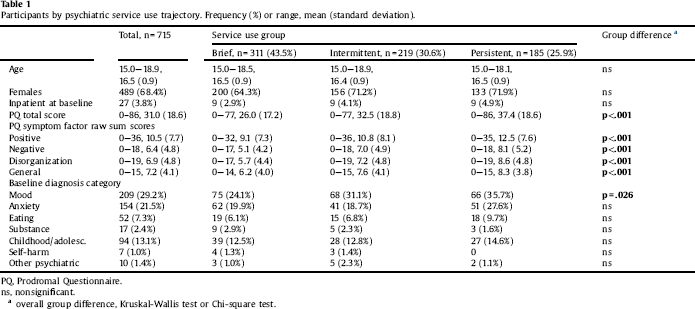

The baseline diagnosis groups of the adolescents can be seen in Table 1, the most common diagnoses falling into the mood disorder category (29.2%). 237 adolescents (33.1%) had not been given any diagnosis between 30 days before and after filling out the PQ. The rest had at least one baseline diagnosis; 423 (59.2%) from one category, 47 (6.6%) from two categories, and 8 (1.1%) from 3 or 4 categories. For further analyses, the adolescents were dichotomized in 0–1 diagnostic categories versus 2–4 diagnostic categories (multimorbidity).

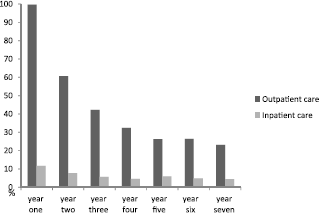

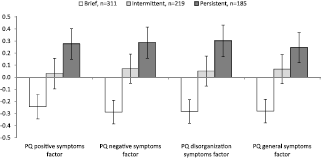

The rates of psychiatric treatment over the follow-up time can be seen in Fig. 1. Patterns of long-term trajectories were identified based on psychiatric service use during the seven first years after the first psychiatric visit. Of the adolescents, 311 (43.5%) were classified to the Brief contact group, 219 (30.6%) to the Intermittent contact group, and 185 (25.9%) to the Persistent contact group (Table 1). All baseline PQ scores were the highest in the Persistent group and lowest in the Brief group (Fig. 2).

As described in the Methods, diagnosable psychotic disorders at baseline were excluded from the sample. Although transition to psychosis was not the focus of this study, of note, 67 emerging psychosis cases (40 females and 27 males; 9.4% of the whole sample) were identified during the 7-year follow-up from the hospital discharge register. These individuals most often used psychiatric services persistently (76.1%) or intermittently (19.4%) during the follow-up phase.

The predictiveness of each background variable with regards to service use trajectory was investigated with separate multinomial logistic regression models (Supplementary Table 3). Baseline inpatient status, age, or gender did not predict prolonged service use and were therefore not included as covariates in further analyses. Of the baseline diagnosis categories, mood disorders were significantly associated with persistent service use, as was multimorbidity, and these variables were therefore included in the final models as covariates.

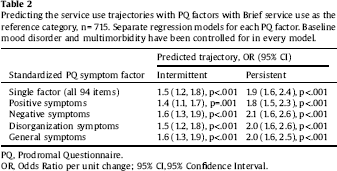

Table 2 shows the parameters of the final models for the four domains of psychosis risk symptom factors and the overall factor. All PQ factors were statistically significant predictors of prolonged (intermittent and persistent) service use, and the differences between the models were small.

Psychosis during follow-up predicted long-term service use (Supplementary Table 3). To see whether the association between baseline psychosis risk symptoms and long-term service use was explained by the subgroup of participants developing psychosis during the follow-up, we repeated the final regression analyses excluding the participants with follow-up psychosis. The results did not change (Supplementary Table 4): all four clusters of psychosis risk symptoms still significantly predicted service use trajectory.

4. Discussion

We wanted to assess whether different types of self-reported psychosis risk symptoms would predict psychiatric service use over the follow-up period of seven years. We investigated non-psychotic adolescents who had been referred to psychiatric care for the first time, using register data of their long-term psychiatric treatment service use. Different psychiatric service needs could be identified in subgroups of adolescents, 44% of the adolescents using services quite briefly, 31% intermittently, and 26% persistently along the seven years of follow-up. The predictive power of psychosis risk symptoms in early or mid-adolescence over later years in adulthood was examined, as the adolescents were followed up until age 22‒25. Correlates of more persistent service use were mood disorders and diagnosis from multiple categories at baseline, as well as negative, general, disorganization, and positive psychosis risk symptoms at the beginning of treatment. Psychosis risk symptoms predicted service use even when developing psychosis during follow-up was accounted for.

Genders did not differ in service use trajectories. A previous study found gender to play a significant role in seeking help for mental health problems [Reference Haavik, Joa, Hatloy, Stain and Langeveld23] but it has to be noted that in the current study, over 2/3 of the participants were female. Furthermore, age was not associated with service use, which might be due to the small variation in age. Inpatient status at baseline also did not predict service use, perhaps due to the small amount of PQs filled out by inpatients.

Mood disorders at baseline were associated with persistent service use. Mood and anxiety symptoms often occur together with positive psychosis risk symptoms and may represent a prodrome of psychosis in some cases, but most individuals presenting with both symptom clusters will not develop psychosis. Previous literature has reported depressive symptoms to contribute to positive psychosis risk symptoms in the general population, suggesting shared vulnerability for affective dysregulation and reality distortion [Reference Van Rossum, Dominguez, Lieb, Wittchen and Van Os24]. In psychosis risk individuals, comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders are common and are associated with lower functioning and worse longitudinal outcome [Reference Fusar-Poli, Nelson, Valmaggia, Yung and McGuire25]. Co-occurrence of affective and positive symptoms is associated with worse outcome in terms of risk of developing psychosis [Reference Krabbendam, Myin-Germeys, Hanssen, de Graaf, Vollebergh and Bak26] and poorer outcome of depressive disorder [Reference Perlis, Uher, Ostacher, Goldberg, Trivedi and Rush27]. In the current study, there was no substantial change in predictiveness when the presence of mood disorders was controlled for, indicating that the predictive power of positive psychotic symptoms did not depend on concurrent mood problems. In addition, psychosis risk symptoms continued to predict service use also when multimorbidity at baseline was controlled for.

Table 1 Participants by psychiatric service use trajectory. Frequency (%) or range, mean (standard deviation).

a overall group difference, Kruskal-Wallis test or Chi-square test.

Fig. 1. Rates of psychiatric treatment over the seven-year follow-up, n = 715.

Fig. 2. Prodromal Questionnaire standardized factor score means and 95% confidence intervals among the three service use trajectory groups, n = 715.

Table 2 Predicting the service use trajectories with PQ factors with Brief service use as the reference category, n = 715. Separate regression models for each PQ factor. Baseline mood disorder and multimorbidity have been controlled for in every model.

Our results indicate that it might be possible to distinguish patients with longer need for care by assessing psychosis risk symptoms at initial psychiatric help-seeking. Our results are congruent with earlier studies linking positive symptoms of young people with poorer illness course and greater service use [Reference Wigman, van Nierop, Vollebergh, Lieb, Beesdo-Baum and Wittchen7]. In adolescents with non-psychotic psychiatric disorders, those with co-occurring positive psychosis risk symptoms showed non-adaptive coping and poorer functioning compared to patients without positive symptoms [Reference Wigman, Devlin, Kelleher, Murtagh, Harley and Kehoe28]. Bhavsar and colleagues [Reference Bhavsar, Maccabe, Hatch, Hotopf, Boydell and Mcguire9] similarly linked data of subclinical psychotic symptoms with prospective health records, finding that they were related to subsequent mental healthcare need and longer treatment in the general population. Among psychiatric outpatients, positive psychosis risk symptoms were associated with higher levels of symptomatology across various diagnostic domains indicating general clinical severity [Reference Gaudiano and Zimmerman29]. In a youth cohort, those with psychosis risk symptoms at baseline but not at 2-year follow-up nonetheless scored higher on symptoms and lower on functioning at follow-up, as compared to youths without baseline psychosis risk symptoms [Reference Calkins, Moore, Satterthwaite, Wolf, Turetsky and Roalf30]. In the adult population, positive psychosis risk symptoms increased the risk for psychiatric hospitalization in a dose-response manner [Reference Werbeloff, Drukker, Dohrenwend, Levav, Yoffe and van Os13], the probability of help-seeking increasing as a function of multiple positive symptoms [Reference Murphy, Shevlin, Houston and Adamson11]. Positive risk symptoms may thus be complicating factors in non-psychotic illness, associated with more severe psychopathology [Reference Wigman, van Nierop, Vollebergh, Lieb, Beesdo-Baum and Wittchen7]. These findings indicate how positive psychosis risk symptoms may be unspecific indicators of general mental health and the severity of the challenges the person is facing. In line with this, it has been suggested that positive symptoms may be a marker of the more severe end of a common mental distress continuum in teenagers [Reference Stochl, Khandaker, Lewis, Perez, Goodyer and Zammit31].

The PQ not only includes positive psychotic symptoms but also negative, disorganized, and general psychosis risk symptoms. Of note, not only positive risk symptoms were predictive of more persistent service use, but negative, general and disorganized risk symptoms were equally predictive. The role of negative symptoms as psychosis risk symptoms is somewhat underrepresented [Reference Fusar-Poli and Borgwardt32] as the ultra-high risk and clinical high-risk criteria are based on positive symptoms only. However, studies show that the negative symptom cluster also is predictive of psychosis [Reference Addington and Heinssen16] and poorer functioning [Reference Cotter, Drake, Bucci, Firth, Edge and Yung17]. Different symptom clusters can be difficult to separate from each other; once one of these symptom clusters exacerbate, so do the others [Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Green, Horan, Subotnik and Mintz33–Reference Van Os and Linscott35]. Also in the current sample, the symptom factors were highly correlated with each other. As it seems that positive psychosis risk symptoms often overlap with negative or depressive symptoms, the PQ could be an asset in preliminary assessment of psychiatric patients as it incorporates all of these risk symptom clusters.

The four factor model of psychosis risk symptoms followed the a priori classification of the PQ instrument [Reference Loewy, Bearden, Johnson, Raine and Cannon20]. It was used instead of others models (e.g. our previous 9-factor solution [Reference Therman, Lindgren, Manninen, Loewy, Huttunen and Cannon36]) to reduce the number of tested variables and enhance clinical usability of the results. Positive psychosis risk symptoms were here investigated as one construct, but subdimensions of positive symptoms may affect psychopathology differently. For instance, persecutory ideation and bizarre experiences may subjectively be more disruptive, whereas magical thinking and grandiosity might not confer distress and be as suggestive of psychopathology as other positive risk symptoms [Reference Yung, Nelson, Baker, Buckby, Baksheev and Cosgrave37, Reference Armando, Nelson, Yung, Ross, Birchwood and Girardi38]. In one study in a non-clinical sample, of different positive symptoms, only auditory perceptual disturbances were associated with need for psychological services, when neurotic traits, anxiety, and depressive symptoms were controlled for [Reference Demmin, DeVylder and Hilimire39].

Some types of positive psychosis risk symptoms may cause more distress and affect help-seeking more than others. Not all positive symptoms lead to need for care [Reference Peters, Ward, Jackson, Morgan, Charalambides and McGuire40], and a distinction can be made between subclinical psychotic symptoms that generate distress and help-seeking and the more common psychotic-like experiences that do not [Reference van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul and Krabbendam1, Reference Linscott and van Os3]. The individual’s appraisal of the positive symptom is of great importance with regards to associations with psychopathology [Reference Yung, Buckby, Cotton, Cosgrave, Killackey and Stanford41], and the level of distress caused by symptoms is a major factor on whether the person seeks for help [Reference Bak, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul, Vollebergh, De Graaf and Van Os42]. A previous study indicated that magical thinking also is associated with psychopathology if it is accompanied with distress [Reference Yung, Buckby, Cotton, Cosgrave, Killackey and Stanford41], and another study found that hearing voices was the only symptom connected to help-seeking when perceived distress was controlled for [Reference Bak, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul, Vollebergh, De Graaf and Van Os42].

In non-psychotic psychiatric disorders, positive psychosis risk symptoms are common [Reference Rietdijk, Fokkema, Stahl, Valmaggia, Ising and Dragt43]; the impact of positive symptoms and psychiatric disorders being reciprocal, as both may affect the other. Having positive symptoms may increase the distress caused by a psychiatric disorder, or, conversely, having a psychiatric disorder may give rise to psychosis risk symptoms and affect the way they are attributed [Reference Rössler, Hengartner, Ajdacic-Gross, Haker, Gamma and Angst44]. There may also be shared vulnerability factors behind the two [Reference Breetvelt, Boks, Numans, Selten, Sommer and Grobbee45]. As risk symptoms do not necessarily cause distress [Reference Linscott and van Os3], the person having them may not seek for help; however, having a psychiatric disorder may create or intensify the feelings of distress and lead to help-seeking even though psychosis risk symptoms themselves may not [Reference Kobayashi, Nemoto, Murakami, Kashima and Mizuno46]. These findings indicate the importance of distress to help-seeking behavior.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This prospective study utilized a large sample of 15–18 year-olds who had been referred to psychiatric care for the first time; the results can be generalized to general psychiatric care in the adolescent age group. Previous studies have often relied on self-reported service use [Reference Bhavsar, McGuire, MacCabe, Oliver and Fusar-Poli14], vulnerable to recall bias. Objective service use data with the seven-year register follow-up were available in the current study, enabling detecting trajectories in help-seeking behavior. The service use group definitions were made to be easily understood and replicable.

Service need is not the same thing as service use, as some adolescents may have needed help for a longer time but did not continue using the services due to, for instance, unwillingness, inability, or service availability. In other words, longer service use only partly reflects the severity of mental health problems. Another limitation was that we obtained information only from public services – however, private service use is not common among adolescents in Finland.

The information of the participants’ baseline diagnoses was available and was used as a covariate, so the association between psychosis risk symptoms and service use was not simply attributable to the influence of concurrent mental health disorders. Due to power considerations, the grouping of the diagnoses was rough and did not take into account the varying severity level of the various diagnoses included in each group. In addition to this diagnosis information, only the PQ was available for the whole sample, and controlling for the possible confounding effects of other concurrent mental health symptoms or level of functioning was not possible.

In the current study, there was no information on how distressing the psychosis risk symptoms were to the participants, as the PQ version with only Yes/No answers was used. Screening effectiveness of the PQ could be improved by including the distress criteria when probing for psychosis risk symptoms [Reference Savill, D’Ambrosio, Cannon and Loewy47], as in the PQ-B.

4.2. Conclusions

The current study examined how different types of psychosis risk symptoms may predict psychiatric treatment in a seven-year follow-up using a clinical adolescent sample. We wanted to explore whether it is clinically useful to screen for psychosis risk symptoms predicting longer need for care. Identifying different treatment needs and the more harmful psychosis risk symptoms may improve care offered to adolescents seeking help, by targeting otherwise unidentified symptoms for treatment. In the context of psychosis-risk intervention studies, symptom-specific treatment has been shown to decrease symptom levels [Reference McGorry, Nelson, Amminger, Bechdolf, Francey and Berger48], which is relevant to a much larger patient group than those deemed to be at elevated psychosis risk.

In this sample of adolescents of 15–18 years of age, it was found that psychosis risk symptoms assessed at the beginning of treatment were associated with long-term psychiatric service use. Thus, even though these symptoms are not always indicative of psychopathology – let alone psychosis – they have an association with persistent service use in help-seeking adolescents. Assessing psychosis risk symptoms of adolescents at the beginning of treatment may help to predict their need for care for the upcoming years, and to target interventions.

Attenuated positive symptoms act as a marker of stress and mental suffering [Reference Van Os and Linscott35] and predict psychiatric treatment needs later in life. This study adds to the previous literature in showing that negative, disorganization, and general psychosis risk symptoms may be equally predictive of the severity of mental health challenges as the positive risk symptoms are. Psychosis risk symptoms thus do not only partially predict psychotic and non-psychotic disorders but also prolonged need for care among psychiatric patients, irrespective of diagnosis category. Assessing all the psychosis risk symptom dimensions of a young person entering psychiatric care is therefore meaningful, regardless of any indications of heightened psychosis risk, as all the dimensions are predictive of long-term need for care.

Funding body agreements and policies

This study was funded by the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation (#6781 to ML), the Juho Vainio Foundation (ML), and the Academy of Finland (#311578 to MJ). The funding organizations played no further part in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in writing of the paper.

Conflict of interest

ML has received an interview honorarium from Lundbeck. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Marjut Grainger and the whole Helsinki Prodromal Study work group, as well as all the participants of the study.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.10.004.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.