The when and why of the ‘Conspiracy theory’ research agenda

The attention to the spread of conspiracy theories increased significantly in Western countries since 2016, on the occasion of the Brexit referendums (Swami et al., Reference Swami, Barron, Weis and Furnham2018) and the US presidential elections (Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, DeWitt, Uscinski, Lucas, Galdieri and Sisco2017). In those two cases, the propaganda supporting the positions and leaders that turned out to be victorious was interwoven with narratives about alleged conspiracies. The attention to conspiracism and conspiracy theories was fueled in the following years by the increasing spread of ‘alternative explanations’ concerning the alleged dangerousness of vaccines that would be deliberately hushed up by public institutions and multinational drug companies. Such theories have then flourished together with the Covid-19 pandemic years. Concerns about this phenomenon peaked in 2020, with the most serious challenge to democratic institutions that the United States has experienced in modern times (the assault on the U.S. Capitol Hill, mainly based on false claims of an – undemonstrated – gigantic electoral fraud, see Amarasingam and Argentino. Reference Amarasingam and Argentino2020).

As it is well known, many of those theories have become popular in recent years, both in the US and in Europe (see Oliver and Wood, Reference Oliver and Wood2014; Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017). Of course, unproven conjectures about possible conspiracies cannot always be considered as degeneration of public debate. In liberal democracies, indeed, the widespread control exercised on political power by the public opinion, independent media, and competing political forces is also achieved through the doubts raised about illegal/harmful activities that are usually perpetrated by small, secret groups of powerful people.

In any case, the propagation of conspiracy theories as a means of political propaganda is by no means a new phenomenon. The idea that a small core of powerful and malevolent actors conspire in the shadows to the detriment of the people is well-established and recurrent in pre-enlightenment religiously motivated narratives (Naphy, Reference Naphy2002). In modern times, and especially in situations of societal crisis, it seems that these theories are more likely to spread and be accepted by the general population (Van Prooijen and Douglas, Reference Van Prooijen and Douglas2017). In its secularized second life, conspiracism has been argued as an integral part of the most influential ideologies of the first half of the 20th century (Popper, Reference Popper2012) and was consequently seen as an essential component of the official political doctrine of the fascist, Nazi, and Soviet regimes, as well as it is often an integral part of the ideology of revolutionary movements or terrorist organizationsFootnote 1. The idea that domestic actors were part of a plot orchestrated by enemy powers recurred in the political propaganda of both blocs during the Cold War in the 1950s. In the sixties and seventies, conspiracy theories arise mainly as interpretations of events in which domestic political institutions and parts of the establishment were suspected of having conspired against the common good, as, for instance, in the case of the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. The 1960s and 1970s represent the moment in which the political incorrectness of such kind of public discourse begins to be stigmatized (Butter, Reference Butter2014; Butter and Reinkowski, Reference Butter and Reinkowski2014). With the start of the new millennium, marked by the attack on the World Trade Center, conspiracy theories returned to be recurrent in the public conversation and to be the object of increasing attention by social scientists (Sunstein and Vermeule, Reference Sunstein and Vermeule2009; Uscinski, Reference Uscinski2018; Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Sutton, Cichocka, Nefes, Siang Ang and Deravi2019).

The scientific literature, to date, has attempted to define in a conceptually clear way the object of research and its characteristics: social psychologists – above all – have investigated the individual predispositions underlying the propensity to believe in such theories (Goreis and Voraceck, Reference Goreis and Voracek2019); communication scholars have investigated the impact on the diffusion of such theories of social media (Bessi et al., Reference Bessi, Zollo, Del Vicario, Scala, Caldarelli and Quattrociocchi2015; Zollo et al., Reference Zollo, Kralj Novak, Del Vicario, Bessi, Mozetič, Scala, Caldarelli and Quattrociocchi2015); political scientists have focused on the relationships between political orientations and willingness to adhere to conspiracy theories, as well as the role played by political leaders in nurturing, propagating, or exploiting for their own electoral ends such beliefs (see Enders and Smallpage, Reference Enders and Smallpage2019a); scholars from various fields have highlighted the impact of belief in conspiracy theories on several important aspects of social life (Jolley and Douglas, Reference Jolley and Douglas2014; Lewandowsky et al., Reference Lewandowsky, Gignac and Oberauer2013). An aspect that is so far neglected concerns the ‘life cycle’ of conspiracy theories, and the reasons for their stability or decline over time.

In this paper, we will focus on the defining issues that underlie the research agenda around conspiracism, by briefly recapping the state of the art on various aspects of the topic (underlying factors, communicative context, social effects) and by warning about possible stretching of the ‘conspiracy theory’ concept. Further, we elaborate on the last one (life cycle). In this regard, previous empirical studies have only analyzed how conspiracy theories change over a reduced period (e.g., before and after an election, see Miller et al., Reference Miller, Farhart and Saunders2021). Using panel survey data, we take a longer-term approach. For our analysis, we draw on surveys conducted in late 2016 and late 2020 in which respondents were asked to rate the plausibility of different ‘classic’ conspiracy theories (such as the one arguing that the Moon landing was fake and the one theorizing the so-called ‘chemtrails’). We can thus compare changes in beliefs in these conspiracy theories over this 4-year time frame. The results show that the number of people who believe in these theories decreases. We show that this decline can only be marginally explained by individual socio-demographic characteristics or political orientations. After thoroughly describing these longitudinal differences, we formulate several hypotheses to speculate on the causes of this decline, mainly focusing on the impact of media coverage of conspiracism over time. Using the online tool MediaCloud, we collect from mainstream media outlets articles published from October 2016 to September 2020 in which the conspiracy theory topic is covered with neutral or derogatory terms, showing that this latter type of coverage rapidly becomes more relevant, especially with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a tentative hypothesis, we thus argue that this increasingly negative coverage might have led people to sincerely change their minds, or hide their true opinion in the survey due to social desirability mechanisms.

Definitions and concept stretching

Building on Uscinski and colleagues' argument (Uscinski et al., Reference Uscinski, Klofstad and Atkinson2016: 2), we can define conspiracy theories as ‘attempts to explain significant social and political events and circumstances by implausibly claiming that they are the ultimate and consciously pursued effect of a secret conspiracy led by a group of powerful and malevolent actors’. This formulation reflects what has emerged from earlier philological work (Pigden, Reference Pigden1995; Keeley, Reference Keeley1999) and, beyond marginal lexical variations, defines the concept consistently to most studies on the subject.

In this context, the term ‘theory’, as opposed to in the scientific jargon, denotes a contrived conjecture regarding an improbable or nonexistent conspiracy, generally refuted by a multiplicity of epistemic communities or reliable sources of information. The conspiracy, in all likelihood, does not exist. Rather, there is only a ‘theory’. In adherence to common usage, we tend to define ‘conspiracies’ as those that have been established or deemed plausible by the relevant epistemic authorities and call ‘conspiracy theories’ the conjectures about conspiracies that have been widely rejected by epistemic communities.

In the meaning of the original Latin term and the Anglo-Saxon legal lexicon, a ‘conspiracy’ occurs whenever two or more individuals work together to commit a crime. However, the term ‘conspiracy theories’ refers to much more complex machinations, based on a ‘diabolical’ plan (that is both malevolent and extraordinarily efficient), conceived for the benefit of a few and to the detriment of many, to direct social or political phenomena by deceiving the public. Conspirators are seen as agents who are extraordinarily capable of influencing large collective phenomena through a complex causal chain and controlling a substantial number of people directly or indirectly involved in the conspiracy, to maintain secrecy about their plan (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2014). A series of suggestive pieces of evidence, usually strategically cherry-picked by conspiracists, are employed to connect the conspirators' intentions and the events that they allegedly produced. As a result, social events appear as a straightforward consequence of the conspirators desires: as an example, the theory declaring that ‘9/11 was an inside job’ orchestrated by the US government, starts from the standpoint that the US wanted to invade (for economic and political reasons) Afghanistan, then it collapsed the WTC towers, getting the desired result. A more recent conspiracy theory states that the multinational drug companies have a vested interest in selling vaccines; consequently, they produced and disseminated Covid-19, getting the result of making more profits. In this sense, conspiracy theories provide a simple explanation of complex phenomena. The simplicity of the ‘theories’ lies in the straightforward relationship between the intentions of the conspirators and the pursuit of their goals. However, conspiracy theories do not always involve a simpler account of the events than those provided by public institutions or epistemic communities. Indeed, the path by which conspirators can fulfill their desires is almost inevitably more convoluted, having to include dissimulations and red herrings. For example, the so-called ‘controlled demolition’ narrative is certainly more convoluted than the narrative that the World Trade Center towers collapsed because of collision and combustion produced by the hijacked airplanes.

The apparent simplicity of conspiracy theories has, in fact, a strong affinity with people's attributional processes, namely, the processes according to which individuals infer causes and consequences of events. Conspiracy theories usually mimic the same biases that people experience when they make causal and responsibility attributions (Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, McClure and Slugoski2005). As Sloman and Lagnado (Reference Sloman and Lagnado2015) put it ‘what people care about when they think causally, beyond just patterns of dependency, is a narrative-like unfolding of events over time. The process of mental simulation helps to construct such narratives. It supports much of our reasoning but currently eludes a strict formal analysis.’ (Sloman and Lagnado, Reference Sloman and Lagnado2015: 241). Consistent with this idea, a conspiracy theory is often a much more intriguing and seductive story with respect to mainstream narratives (Lamberty and Imhoff, Reference Lamberty and Imhoff2021). As an additional competitive advantage of conspiracy theories to strict logical analyses, we can also add that individuals usually prefer deterministic and controllable causes with respect to probabilistic and uncontrollable factors (Girotto et al., Reference Girotto, Legrenzi and Rizzo1991; Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, McClure and Sutton2010), as well as human factors to natural ones (Catellani et al., Reference Catellani, Bertolotti, Vagni and Pajardi2021). Therefore, conspiracist explanations of events could make intuitively more sense than alternative explanations, despite being objectively more convoluted.

Although many authors would agree with the way in which we just circumscribed the concept of interest, a recurring risk of conceptual stretching (Sartori, Reference Sartori1970) is usually present in various works dealing with conspiracies, especially when researchers end up adopting the common and journalistic broadened meaning of the expression. As Walker stresses, “people started using the phrase conspiracy theory to mean ‘implausible conspiracy theory’, then ‘implausible theory’, whether or not it involves a conspiracy’” (Walker, Reference Walker and Uscinski2018). The first semantic slippage – ‘conspiracy theory’ used as a synonym for ‘implausible conspiracy theory’ widely refuted by the relevant epistemic communities – consists of a pure linguistic convention; if this slippage is previously stated, it does not make the concept ambiguous. The second semantic shift is instead problematic. Following the political and journalistic lexicon in that direction would bring under the category of ‘conspiracy theories’ any kind of unfounded accusation or theory.

Let us take an example about two of the most popular conspiracy theories in the United States today. The first is the alleged ‘controlled demolition’ of the three World Trade Center towers by U.S. government operatives, which falls squarely within the most circumscribed and pertinent definition of conspiracy theory. Much less precise is the definition of conspiracy theory as the one stating that Barack Obama was born in Kenya and his birth certificate was forged. If we include this latter story in the definition of ‘conspiracy theory’, we should consider under that term all forms of defamation, slander, and backbiting circulated to discredit an eminent public figure or to feed a latent prejudice already present in a part of public opinion toward him/her. Let us take, as an additional example, the story according to which the pandemic was caused by Big Pharma companies to sell vaccines, or the other arguing that all the vaccines are propelled by a rigged system, harm the immune system, and expose it to diseases. According to the previous definitions, these two arguments fall among the conspiracy theories concept in the most circumscribed and analytically useful meaning. But what about those who fear that the anti-Covid vaccine may have negative effects – not predicted by the experiments conducted so far by scientific institutions – in the long term, to the point of being against being vaccinated, even at the risk of endangering their own health (or life) in the short term? This belief can be motivated by an arbitrary calculation of probabilities, by ignorance about the protocols used to validate the vaccine, by distrust toward the predictive capabilities of science, or by some sort of phobia or hesitancy, without however implying any conjecture about implausible conspiracies.

All in all, we can stress that conspiracy theories in which we are interested are: (1) theories decisively refuted by the epistemic communities, (2) attributing to a small core of powerful conspirators (3) the ability to conceive and pursue a machination intended to consciously influence broad social phenomena or public understanding about events of great collective importance, (4) coordinating a broader coalition composed of their agents (5) who help implement the plan and maintaining secrecy about its real purposes and principals (see Van Prooijen Reference Van Prooijen2018: 5–6, for a similar conclusion). To date, research on the topic has attempted to identify underlying individual factors, facilitating elements of the communicative context, and possible social effects of the propensity to make such beliefs one's own.

Underlying individual factors, the media context, social outcomes

A considerable number of studies have focused on the relationships between various psychological traits and the likelihood of believing in unlikely conspiracies. In particular, the literature has shown that low levels of self-esteem (Abalakina-Paap et al., Reference Abalakina-Paap, Stephan, Craig and Larry Gregory1999; Furnham, Reference Furnham2021), paranoid ideation, schizotypy, and high levels of need for cognitive closure (Marchlewska et al., Reference Marchlewska, Cichocka and Kossowska2018) tend to increase beliefs in conspiracy theories. Cognitive capacities are also deemed to be connected with conspiracist ideation: Swami et al. (Reference Swami, Voracekb, Stiegerbc, Tranb and Furnhamd2014) show that beliefs in conspiracy theories are connected with low levels of analytical thinking, while Martini et al. (Reference Martini, Guidi, Olmastroni, Basile, Borri and Isernia2022, in this special issue) studied the link between conspiracy mentality and the ability to correctly perceive relevant political facts or social phenomena: They show that the conspiracist mindset correlates with innumeracy, the inability to deal with numbers and to provide correct estimates about political and social phenomena.

Another attitudinal element that has been identified as a strong predictor of conspiracism is represented by religiosity. Conspiracism can be theoretically associated with a belief that attributes to unseen forces the responsibility of relevant (and usually shocking) events (Oliver and Wood, Reference Oliver and Wood2014; Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017). This way of reasoning has been demonstrated to be associated also with some form of religiosity. In particular, recent research (see, for instance, Ladini Reference Ladini2022 in this special issue) has shown that people presenting alternative religious beliefs (e.g. the belief in reincarnation) present a stronger relationship with conspiracist ideation.

It has also been argued that conspiracy ideation is heavily influenced by individuals' liberal-conservative self-positioning. Specifically, previous research has shown that conservatives tend to be more susceptible to conspiracy theories than liberals (van der Linden et al., Reference van der Linden, Panagopoulos, Azevedo and Jost2021). A growing strand of research has hypothesized the existence of a link between populism (especially right-wing populism) and conspiracy theories (Enders and Smallpage, Reference Enders and Smallpage2019a, Reference Enders and Smallpage2019b). Some of the core elements of populism (Manichean attitudes, the strong differentiation between the elite and the people) have been seen as the root of an alliance between these two worldviews (Hameleers, Reference Hameleers2021). Political orientation can also be a moderator of the effect of other variables on conspiracism. In this special issue, for instance, Vezzoni et al. (Reference Vezzoni, Dotti Sani, Chiesi, Ladini, Biolcati, Guglielmi, Maggini, Maraffi, Molteni, Pedrazzani and Segatti2022) suggest that the main factor driving beliefs in alternative accounts on the origins of the virus is institutional trust, but political orientation moderates its effects, depending on specific conditions (e.g. the position of the supported party either in government or opposition), and eventually reinforcing skepticism toward epistemic authorities for those having low trust in institutions.

Subjective conspiratorial predispositions are increasingly exploited by populist leaders to mobilize latent anti-establishment biases and increase their own support. This hypothesis corresponds to the general claim that individual predispositions to conspiracy theories are prone to be triggered under conditions of power differentials, exclusion from political authority, and perceived threats (Oliver and Wood, Reference Oliver and Wood2014; Uscinski and Parent, Reference Uscinski and Parent2014; Uscinski et al., Reference Uscinski, Klofstad and Atkinson2016).

Previous literature has also investigated the relationship between the spread of conspiracy theories through social media. Individuals with a conspiracy mindset are reluctant to accept news from mainstream media, which are perceived as being entangled with the same powerful organizations that are conspiring, and show a preference for grassroots outlets that provide a more genuine/independent account of what is really going on (Stempel et al., Reference Stempel, Hargrove and Stempel2007; Oliver and Wood, Reference Oliver and Wood2014). The social media bubbles in which conspiracy theories spread – a complex network of Facebook groups, pages, and Twitter accounts created specifically to spread and discuss conspiracy theories – have also been studied. The relationship of those pages with bubbles engaged in debunking those beliefs has also been investigated (Bessi et al., Reference Bessi, Zollo, Del Vicario, Scala, Caldarelli and Quattrociocchi2015; Zollo et al., Reference Zollo, Kralj Novak, Del Vicario, Bessi, Mozetič, Scala, Caldarelli and Quattrociocchi2015), as well as the possible role of a number of ‘core conspiracist’ users, who can be defined as ‘prosumers’ of those theories – i.e. users able to modify and re-discuss theories, providing original interpretations of them (Zollo et al., Reference Zollo, Bessi, Del Vicario, Scala, Caldarelli, Shekhtman, Havlin and Quattrociocchi2017).

As briefly stressed above, the impact of conspiracy theories is far from small in contemporary democracies: in many European countries, for example, the spread of conspiracy theories about big pharmaceutical companies has been shown to contribute, among other elements, to vaccination choices of parents (Jolley and Douglas, Reference Jolley and Douglas2014; Giambi et al., Reference Giambi, Fabiani, D'Ancona, Ferrara, Fiacchini, Gallo, Martinelli, Pascucci, Prato, Filia, Bella, Del Manso, Rizzo and Rota2018). This trend has been shown to jeopardize the achievement of the same goal with regard to Covid-19 vaccine campaigns (Sallam et al., Reference Sallam, Dababseh, Eid, Al-Mahzoum, Al-Haidar, Taim, Yaseen, Ababneh, Bakri and Mahafzah2021). In short, conspiracy theories spread distorted perceptions of reality regarding phenomena with high social impact. Individual predispositions to accept those perceptions of illusory patterns can be exploited to sell narratives that promote distrust of the scientific community and the democratic process, to fuel racist prejudices, and urge criminal and anti-democratic actions. For instance, Vegetti and Littvay (Reference Vegetti and Littvay2022, in this special issue), by working on the political-behavioral implications of conspiracy beliefs, have shown that conspiracist people are more likely to endorse political violence and legitimate radical political action.

In addition to health behaviors, thus, believing in conspiracy theories increases distrust in political institutions (e.g., Einstein and Glick Reference Einstein and Glick2015), and provides ideological elements for processes of violent polarization that can even threaten the liberal democratic order (e.g., Amarasingam and Argentino Reference Amarasingam and Argentino2020). Conspiracy mindsets and belief in specific theories can guide voting behaviors and the positioning on binary choices, as in the case of referendums. Evidence of this type has been provided about the 2016 US presidential election, as well as the referendum on Brexit in the UK (Jolley et al., Reference Jolley, Douglas, Marchlewska, Cichocka and Sutton2021) and the revision of the constitution in Italy in the same year (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2020).

The life cycle of conspiracy theories

While the research agenda on conspiracies is already well structured with respect to previous items, we still know little about the stability of conspiracy beliefs over time. Yet this is not a marginal issue. By studying how conspiracy beliefs change over time, we can learn the extent to which they reflect structured or superficial opinions, and how resistant they are to the rebuttals spread to counter them. To date, these questions have been little developed in the literature (Uscinski et al., Reference Uscinski2018). If it is true that social media are a vehicle structurally geared toward promoting false beliefs, these channels of communication should not only facilitate the notoriety of the theories but also their continued dissemination over time. On the contrary, one can hypothesize that social media only make more transparent (publicly visible) predispositions, attitudes, and beliefs that have always existed, thus promoting both a rapid diffusion of conspiracy theories and an equally rapid counteraction by those who adhere to mainstream interpretations. Incidentally, the exercise conducted in this regard by Uscinski and colleagues has, in our opinion, the drawback of being related to a false belief (the veracity of Barack Obama's birth certificate) that does not completely fit the conceptually neat definition of a ‘conspiracy theory’. It is also based on an indicator of public interest (the recurrence of Google searches for ‘Obama's Birth Certificate’) rather than a longitudinal measure of conspiracy beliefs.

In this contribution, we have the opportunity to present the results of a survey specifically designed for measuring the stability of belief in four of the most popular conspiracy theories among the Italian public, over a 4-year period. The available data allow for now only to refute the hypothesis that the resilience of conspiracy beliefs is explained by the same individual predispositions that explain the initial adherence. In the last part of the article, we will therefore propose two possible alternative explanations: (1) the media persuasive effect hypothesis (i.e., the fact that the negative coverage of such theories produced in the public debate might have changed people's minds); (2) the social desirability effect hypothesis (the fact that this same derogatory way of representing conspiracy might have discouraged people from expressing their true opinions on the topic).

Data and variables

As pointed out above, we aim at investigating what changes have occurred in Italians' beliefs in ‘classic’ conspiracies, during a 4-year period. To do so, we rely on data from the 2013–2020 online panel of the Italian National Election Study (ITANES) and the University of Milan. Interviews were administered through CAWI (Computer-Assisted Web Interview) mode. Respondents have been selected from a proprietary opt-in community (SWG, a private Italian research company). The panel aims at reproducing the quotas for age, gender, and regional distribution of the population. The first wave of the panel was collected before the General Elections of 2013. Each year, in general, two waves were collected, before and/or after the main electoral events of the year (like General elections of 2013/2018, European Elections of 2014/2019, and Constitutional Referendum of 2016 and 2020).

In this study, we rely on two waves of the panel, collected shortly after the Constitutional Referendum of 4 December 2016 (between 7 and 13 December 2016) and shortly after the Constitutional referendum of 20–21 September 2020 (more precisely, between 22 and 30 September 2020). Overall, respondents who have been interviewed in both the waves and produced non-missing responses were 1442Footnote 2.

Measures of conspiracy theory beliefs and independent variables

In both the waves of the panel, four questions addressed the issue of conspiracism. Respondents were asked to assess the plausibility of four conspiracy theories, using a 0–10 scale in which ‘0’ meant ‘Not plausible at all’ and ‘10’ meant ‘Completely plausible’Footnote 3. The four statements, which refer to conspiracies that have been long present in the Italian societies over recent decades, read as follows (for a more precise explanation of the theories, please refer to Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017):

(1) ‘Moon landings never happened and the proofs have been fabricated by NASA and the US government’ (‘Moon’)

(2) ‘Vapor trails left by aircraft are actually chemical agents deliberately sprayed in a clandestine program directed by government officials' (‘Chemtrails’)

(3) ‘Vaccines harm the immune system and expose it to diseases’ (‘Vaccines’)

(4) ‘The Stamina method invented by Davide Vannoni for curing neurodegenerative diseases has been obstructed by big pharmaceutical groups’ (‘Stamina’)

Although the first three items are particularly renowned also in other national contexts, the fourth item deserves some additional words, since it refers to the so-called ‘Stamina therapy’, a controversial alternative technique that was allegedly able to cure neurodegenerative diseases. Although a committee of experts totally rejected the efficacy of the method, the relevant coverage on mainstream media of the ‘cure’ led, especially on the internet, to a movement that hypothesized that big pharmaceutical groups might have benefitted from the discredit of the method (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017).

The first section of the results will show descriptively if and how there have been changes in the levels of beliefs in conspiracy theories in the last 4 years. The second section will present a set of regression models to explain the 2016–2020 differences in the levels of each conspiracy theory by means of several socio-political variables. In the model, similar to the original work of Mancosu et al. (Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017) we introduce gender, age, educational level (subdivided in low, medium, and high), political trust (measured using the stealth democracy scale, see Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002 and Appendix 1 for more information of the scale), left-right self-placement (subdivided in left, center-left, center, center-right, right, not located)Footnote 4.

Results

How has conspiracism changed over the 2016–2020 period? The first element of empirical evidence is shown in Figure 1, which represents the conditional means of the 2016–2020 wave by each level of the 2016 wave. In other words, we can see, on average, the change in evaluation that the same respondents have made between 2016 and 2020 by the evaluation that they had made in 2016. Although there are no large differences between conspiracy theories, it is possible to see that, for instance, people who evaluate a conspiracy as totally plausible in 2016 (assigning a ‘10’ score to the conspiracy) are now much more undecided (the average of 2020 evaluations sees a drop of 4–5 points). We can thus conclude that the highest was the level of conspiracism in 2016, the strongest the dropFootnote 5.

Figure 1. Difference of the four conspiracies between 2016 and 2020.

Is there any variable that can explain the drop in conspiracism reported in the previous paragraph? Table 1 aims at answering this question by fitting four linear regression models in which the dependent variable is the difference between the 2020 and 2016 levels of conspiracism for each of the four theories. This parametrization makes the coefficients of the model easily interpretable since a negative coefficient means that a specific category has decreased its beliefs in conspiracism and a positive coefficient means the opposite.

Table 1. 4 OLS regression models to study opinion change in conspiracism

Standard errors in parentheses.

*** P < 0.01, ** P < 0.05, * P < 0.1.

As it is possible to see from Table 1, women tend to decrease more rapidly than men in the 2016–2020 conspiracism level, as well as right-wing people (at least for what concerns the Moon and ‘Chemtrails’ conspiracies). Other significant coefficients see a decrease in conspiracism for people who are higher on the stealth democracy scale. Also interesting is the coefficient for age, which shows that older respondents tended to present lower levels of decrease with respect to younger people. Overall, we might say that those differences are quite small in magnitude, and the R-squared of the models (0.02) confirms us that, more than a single (or a group of variables) explaining the change in conspiracism, we can more talk about a generalized drop. Table 2 further confirms this idea. The table represents the linear predictions of the four models for the variables that present significant coefficients in Table 1. In order to allow the interpretation of the results, predictions for continuous variables have been chosen in the extremes of the independent variables' scales, while predictions for categorical variables are presented with the prediction for the reference category in Table 2.

Table 2. Linear predictions of significant variables in the four models (Table 1 coefficients)

** P < 0.01.

As it is possible to assess in the table, all the predictions are in the negative area of the dependent variable, meaning that, even if the coefficients are significant and positive (see, for instance, age), they depict a situation in which the drop is more or less accentuated, never a situation in which there is a rise in conspiracism.

A further interesting element about Tables 1 and 2 is represented by the fact that, according to Mancosu et al. (Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017), women, young, and right-wing citizens were those who presented higher scores of conspiracism in 2016. These same categories are those showing stronger drops in conspiracism – this is consistent with what is shown in Figure 1.

Possible explanations of the drop in conspiracism: the role of the media

So far, we have descriptively accounted for what happened in our sample, for what concerns the beliefs in specific conspiracy theories. Results show a generalized decrease in conspiracism, which can be explained only marginally by socio-demographic or political variables. It also seems that respondents who were more enthusiastic in 2016 are now more undecided on evaluating as plausible those theories. This can be partially explained by some form of floor effect – people who were already low in plausibility evaluation cannot pass to negative values, while former believers have more ‘room’ in the scale to decrease their evaluations. However, the interesting point here is that, although the public discourse around conspiracy theories has risen in recent years, and especially during the pandemic, the level of beliefs in these same theories decreased significantly. This apparent inconsistency might be related to the way in which the media have treated conspiracy theories in the last few months/years.

Here, we might provide tentative empirical evidence of how mainstream media have become increasingly critical of conspiracism, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic. To do so, we will employ a simple linguistic artifact that pertains to the Italian language. If in English the only way to define the theories of what we are talking about is the term ‘conspiracy theory’, in the Italian language, there are two terms that are generally used as synonyms, but that are generally perceived as having a slightly different meaning. The first ‘cospirazione’ (which is directly connected to the English ‘conspiracy’) is more employed in the academic debate and has a more neutral meaning. The other one, ‘complotto’, is more employed in the media system (see below), and it is generally seen as a derogatory term, usually employed to criticize, or even make fun of conspiracistsFootnote 6. By using the online tool MediaCloud, which massively collects Global News in real-time (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Bhargava, Valiukas, Jen, Malik, Bishop, Ndulue, Dave, Clark, Etling, Faris, Shah, Rubinovitz, Hope, D'Ignazio, Bermejo, Benkler and Zuckerman2021), we have collected from a large number of Italian mainstream media outlets (see Appendix 4 for the list of the outlets) the articles in which the terms ‘cospirazione’ (and their derivative terms, such as ‘cospirazionista’, which means ‘conspiracist’) and ‘complotto’ (with their derivatives such as ‘complottista’) appearFootnote 7. The resulting time series has thus been smoothed by means of a lowess smoothing procedure (bandwidth = 0.6). Proportions of the two terms (and their derivative terms) on the total of articles published by Italian outlets are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Trends of the non-derogatory/derogatory terms in mainstream media defining conspiracies over 4 years.

As it is possible to see from the figure, the interest of mainstream media in conspiracies rises from mid-2019 and even triples its share after the first wave of the pandemic. In particular, derogatory terms (‘complottismo’ and its derivatives) rises, passing from 0.1% of the articles published by the mainstream outlets to 0.3% (although this figure might seem rather small, we have to consider that MediaCloud collects and process on average about 3000 journal articles per day; as a result, a 0.1–0.3% increase means publishing 6 more articles per day discussing conspiracism with respect to the mid-2019 period, about 180 additional articles per month). On the other side, the non-derogatory, neutral term (‘cospirazionismo’) remains stable. If we are correct in defining the term ‘complottismo’ as a derogatory term defining people who believe conspiracy theories, this simple analysis might suggest that conspiracy theories have increased their coverage in the mainstream media landscape, but with a precise negative connotation, which is more likely to stress the logical inconsistencies that conspiracy theories present and the possible dangers that believing in those conspiracies might lead to. This interpretation, and especially the rise of the term ‘complottismo’ in the months of pandemic crisis is consistent with the requests made by international organizations aimed at fighting misinformation about the Covid-19 pandemic, starting from journalists and pundits (European Commission, 2021; Lewandowsky et al., Reference Lewandowsky, Cook, Schmid, Holford, Finn, Leask, Thomson, Lombardi, Al-Rawi, Amazeen, Anderson, Armaos, Betsch, Bruns, Ecker, Gavaruzzi, Hahn, Herzog, Juanchich, Kendeou, Newman, Pennycook, Rapp, Sah, Sinatra, Tapper and Vraga2021).

What might be the consequences of this increased interest of the media (and their general judgment) on the public opinion sphere? Political communication and political psychology detailed the mechanisms that drive change and stability of opinions, according to changes in the media landscape. The political communication literature, by analyzing ‘media effects’, has shown that mass communication effects exist and can be, overall, quite relevant in magnitude (Iyengar and Simon, Reference Iyengar and Simon2000). Mass communication is indeed likely to affect citizens' political ideas through processes of learning (De Vreese and Boomgaarden, Reference De Vreese and Boomgaarden2006). In our case, thus, it might be that a stronger coverage of the logical inconsistencies of conspiracy theories, or the simple fact that mainstream media cover conspiracism in a negative way (Mancosu and Vegetti, Reference Mancosu and Vegetti2020), addressing it as ‘bizarre stories’ (Stempel et al., Reference Stempel, Hargrove and Stempel2007), might have caused the medium-term drop that we have reported above.

We might hypothesize that this new and increased coverage of conspiracism might affect people in two ways: (1) first, it can genuinely change peoples' minds, depolarizing extreme opinions by the aforementioned processes of learning. (2) Second, it can lead to individual processes aimed at hiding ones' true opinion. In this respect, the drop in conspiracism can be partly due to processes of social desirability: people, once realized that their opinion is actually a fringe/non-mainstream opinion, might hide their actual attitudes to avoid the stigma of being perceived as conspiracy theorists (Einstein and Glick, Reference Einstein and Glick2015; Radnitz and Underwood, Reference Radnitz and Underwood2017).

Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this paper was to introduce the special issue by recalling the reasons for the growing interest of the social scientist community in the spread of conspiracy theories and the objectives pursued by the research developed in recent years. We discussed the risks of concept stretching arising from the transposition into the scientific field of the slanted meaning of the concept that is spreading in the mainstream media. We recalled the main conclusions that research in this field has reached so far. We have also explored a hitherto neglected aspect, which we feel is of some importance. We can learn more about the initial reasons for their spread and the most effective way to neutralize their possible negative effects by studying the ‘life cycle’ of conspiracy theories over time. In a quite counterintuitive way, we have shown that a growing interest in conspiracy theories in general (testified by the increased interest in the topic by mainstream media) corresponds to a lesser likelihood to declare to believe in those theories. Using panel data, which collect evidence on the same people over time, we have shown that the drop in believing in any conspiracy theory is generalized and it cannot be explained by any socio-political variable that we have inserted in the model. We provided two possible explanations for this trend, both of them caused by the increased negative coverage of conspiracism and conspiracy theories in the Italian media landscape. We thus argued that this coverage might have changed people's minds, by making them more likely to rationally process some of the conspiracies in which they originally believed and eventually leading them to identify the inconsistencies and logical fallacies that they present (see Swami et al., Reference Swami, Coles, Stieger, Pietschnig, Furnham, Rehim and Voracek2011). Another, more pessimistic, hypothesis, is that, together with the increased negative coverage of the media, in the public's perception, believing in ‘classic’ conspiracy theories became something that might hurt one's reputation – in a very similar way with respect to what found by Altay et al. (Reference Altay, Hacquin and Mercier2020) for what concerns the scarce level of diffusion of fake news.

Our paper presents different limitations that might impinge our conclusions. First, the advantage of having a medium-term panel is partially undermined by having only two waves on which we can answer our research questions. We thus do not know what happened to our sample in between the first and second waves. Knowing this would have added a relevant amount of information and stronger insights on our topic. The second element is that we do not have any way of performing a systematic test of the two mechanisms that might drive this generalized drop in beliefs in classic conspiracy theories. Unfortunately, ITANES data do not provide tracking data of the exposure to specific news items; only more refined individual data that precisely measure the exposure to such negative coverage are needed to assess the plausibility of our argument. So far, thus, the media effect hypothesis remains a hypothesis that needs further empirical validation.

Funding

The research received no grants from the public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp

Appendix 1 Stealth democracy scale

The items measuring truest come from an adaptation of the so-called ‘stealth democracy’ scale (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002). Respondents are asked to express their degree of agreement with a list of statements on, an 0–10 scale. Although the original battery includes a longer list of items, the four items analyzed show high internal consistency and a Principal component analysis shows that they belong to the same latent construct. The following statements were subjected to the respondents:

(1) ‘Parties are necessary to defend special interests of groups and social classes';

(2) ‘People have not enough knowledge or interest to decide about political problems';

(3) ‘Parties guarantee that people can participate in politics in Italy’;

(4) ‘Without parties there cannot be democracy’.

The items present an inter-item correlation of 0.46 (this corresponds to a Cronbach Alpha of 0.77). The final index is a mean of the scores on the four items, ranging from 0 to 10.

Appendix 2 Descriptive statistics

Table A1. Descriptive statistics

Appendix 3 Additional analyses

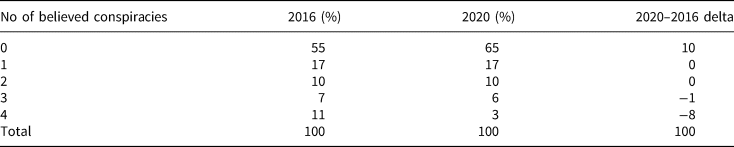

To perform a more thorough investigation of our data, we have designed some additional analyses that explain the longitudinal trends of our conspiracism variables. In Table A2, we attribute a score of 1 when a respondent answers with a level of plausibility equal to or larger than ‘6’. After that, we sum the scores on the four items.

Table A2. Number of believed conspiracies

As it is possible to see, over the 4 years taken into account, the percentage of people who do not believe in any of the conspiracies that have been proposed to the respondents (namely, those who give a score lower than 6 to the plausibility of all the conspiracy stories) rises from 55 to 65%. This happens apparently at the expense of those who used to believe in 3 or 4 conspiracies. Of course, however, this interpretation might be misleading (since we are assessing only aggregate figures).

An additional piece of information might be obtained by analyzing Table A3.

The table shows the differences in distributions of the beliefs in the four conspiracies. Respondents are ordered into three groups: those who ‘firmly do not believe’ in the conspiracy (who answered with a ‘0’ to the question of the plausibility of the conspiracy); those who can be defined as ‘tending not to believe’ in the theory (who answer with a 1 to 5 answer category), and those who ‘believe’ in the conspiracy (those answering ‘6’ or more on the plausibility scale). The table shows, for each conspiracy theory, the percentage difference between the 2016 and 2020 waves.

Table A3. 2016–2020 delta of the four conspiracies (alternative recoding)

As it is possible to see, the group of people firmly not believing the conspiracies strongly increased – he has seen about 20 percentage points increase for what concerns chemtrails and the fake moon landing, and an 8-10 increase for what concerns the vaccine/Stamina theories.

Interestingly, the vaccine conspiracy theory is the one in which the drop has been less relevant: if about 10% of people believing in the conspiracy in 2016 tend to pass to other categories in 2020. For what concerns the ‘vaccines’ conspiracy theory, the part of the sample that starts believing less in it is only the 6%.

Appendix 4

Table A4. MediaCloud outlets considered in the media aggregate analysis