Introduction

Two stone stelae, known as the Balchiria stelae, were discovered in 2017 in the Sartène region of south-west Corsica, on a granite plateau at the junction of the Conca and Avena Valleys. Found by chance, the stelae were probably once part of a now ruined prehistoric monument. Since the discovery of the stelae, geophysical exploration and survey work has been undertaken to explore the area further.

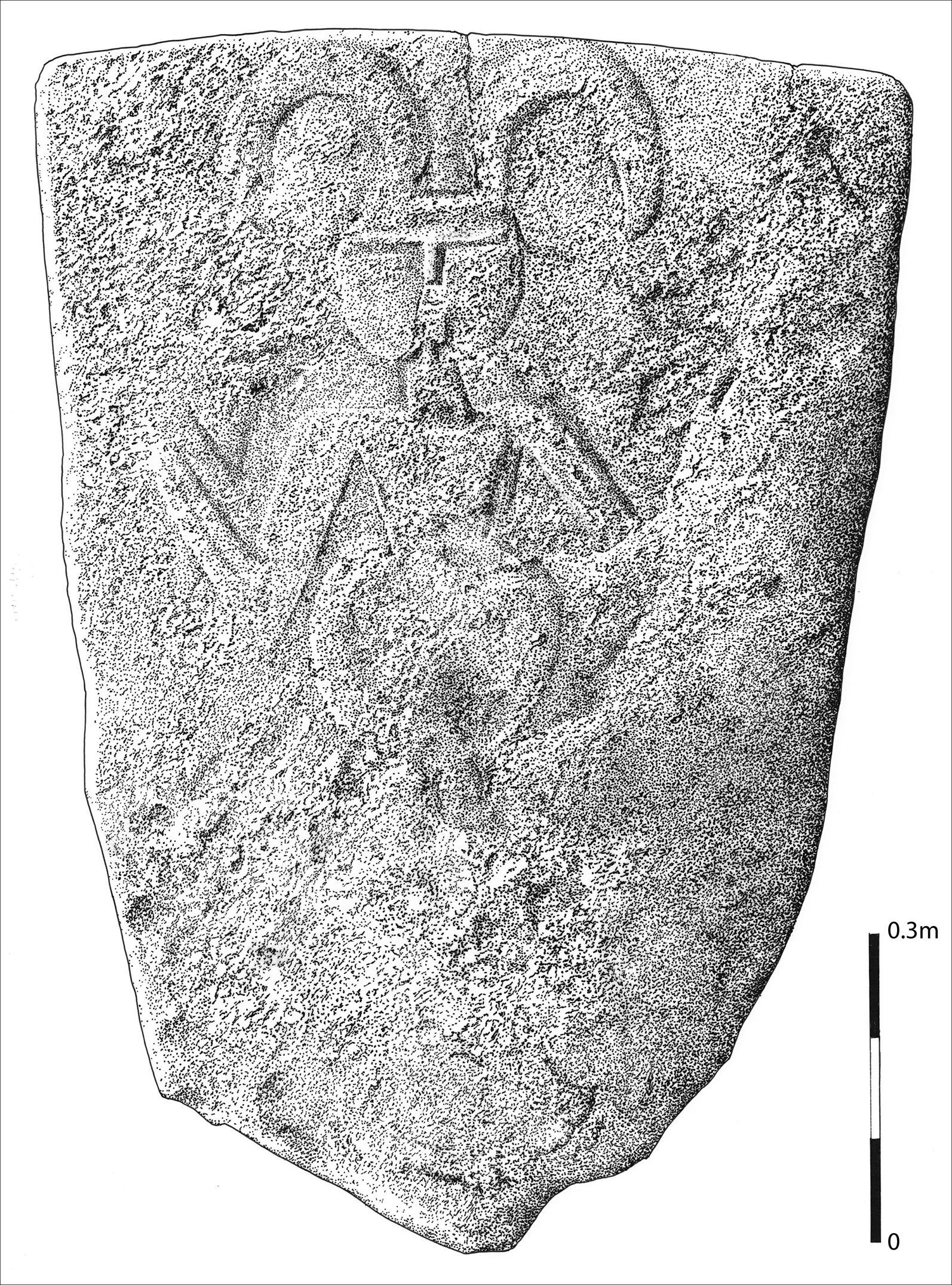

The engraved stela

Stela 1 is a trapezoidal block of stone comprising a broad, plano-convex vertex narrowing at its base. It measures 1.19m in height and 0.81m in width with an average thickness of 0.12m.

An engraved anthropomorphic image covers most of the block except its lower part, which would probably have been hidden if the stela was inserted vertically into the ground. The head of the figure, which features a T-shaped block forming eyebrows and a nose, is capped by two curved appendages that resemble horns (Figure 1). The torso rests above a large circle, which features no explicit representation of lower limbs. The upper limbs are clearly depicted except at their extremities: the right limb is folded into a prayer position, while the left has been depicted only above the elbow (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Engraved stela (photograph by F. Leandri).

Figure 2. Engraved stela drawing (figure by R. Picavet).

The monolith appears to have been quarried from a rocky outcrop, and the engravings etched on the fractured rock face. The edges and vertex of the monolith have been deliberately shaped. The entire figure has been embossed, except the T-block, which combines simple hollowing and false relief (Figure 3). The surface has been ground down (lightly smoothed) around the figure, except at the base and the right side. This may represent an attempt to erase the depiction, or alternatively an effort to polish the surface to achieve contrast between the champlevé (carved relief) and the rest of the stone. The erosion around the champlevé appears to be the result of hammering (percussion lancée) using a stone (Mens Reference Mens2005, Reference Mens2006). In the face area, simple hollows under the T-shaped relief are characterised by a deep, angular line (Figure 3). This could have been produced by a quartz burin used in indirect percussion.

Figure 3. Engraved stela morpho-technological study (figure by E. Mens).

A small crack, a few centimetres long, which has become patinated over time, is located on the highest point of the vertex (Figure 3). Its presence raises the question of whether the stela may once have had a capstone resting on it, but this is unclear. This type of very regular, trapezoidal stela, with a roughly shaped base for fixing it into the ground, experienced a rapid growth in numbers in southern France in the fourth millennium BC, while remaining part of a pre-dolmen phase. Engraved ‘durancian’ stelae from Gargas (Vaucluse) are dated to c. 3900–3800 BC. Undecorated stelae, such as l'Ubac à Goult (Bizot & Sauzade Reference Bizot and Sauzade2015), Vaucluse, Château-Blanc à Ventabren, Bouches-du-Rhône, dolmen de Pouget and Hérault, date to c. 3500 BC (Hasler Reference Hasler1998).

In terms of its iconography, there are comparisons for the figural motifs (Figure 4). Horns are well represented in European Neolithic art, often shown as symmetrical and sometimes as ‘cross sticks’. There are examples in Sardinia, in the form of sculpted or engraved bucrania in the hypogea of the Ozieri Culture (c. 4200–3500 BC). Curved symmetrical horns are also evident on a two-handled vase with protomes (head decoration) from Grotta del Rifugio in Oliena (Lilliu Reference Lilliu1999). Painted anthropomorphic depictions in Iberian schematic art also have horns, such as those at Los Letreros, Doña Clotilde, Peña Escrita de Fuentecaliente and Los Organos (Acosta Reference Acosta1968). In France, schematic horned figures feature on stelae at La Pierre aux Fées (Saint-Micaud, Saone-et-Loire), Jaillance (Die, Drôme), or have been pecked out at rock art sites, such as Mont Bego (Tende, Alpes-Maritimes) (Huet Reference Huet, Guilaine and Garcia2018). The incurved style of the horns on the Balchiria stelae is rarely represented, although not unknown, among Sardinian sculptures.

Figure 4. Engraved stela analysis of constituent parts of the iconographic motif (figure by J. Guilaine).

The depiction of circular faces was an artistic convention that was notably adopted by the craftsmen of marble idols in Late Neolithic Sardinia. Given their geographic proximity, these productions offer the best parallels with the circular face of the Balchiria engraved stela; examples of disc-shaped faces include those at Porto-Ferro, Ponte Secco, Monte d'Accoddi (Sassari), Littoslongo (Ossi) and Anghelu Ruju (Alghero) (Lilliu Reference Lilliu1999).

The combination of the horizontal bar of the eyebrows and the vertical line of the nose was produced using a champlevé technique so that it appears distinctly raised in relation to the rest of the face, which is more withdrawn. The T-block is a classic convention of Neolithic iconography. It can be seen in Italy on Middle Neolithic figurines (red-banded ceramic culture: Passo di Corvo, Foggia; square-mouthed vase culture: Arene Candide, Finale Ligure; Vicofertile, Parma) and Late Neolithic productions (Serra d'Alto Culture: Grotta Pacelli, Bari and the Diana Culture: Arnesano, Lecce) (Guilaine Reference Guilaine1994). In Sardinia, the T-block has been observed from the fifth millennium BC on statuettes of the Bonu Ighinu Culture (Cucurru S'Arriu, Oristano, Meana sardo, Polu). In Corsica, it is present on the small figurine at Campu Fiurelli (Grosjean Reference Grosjean1966). Most Western statue menhirs have also made use of it (Rouergue, Languedoc, Aosta-Sion and Lunigiana) (Arnal Reference Arnal1976).

The eyes are not depicted and the mouth is represented by two short horizontal lines. The neck clearly separates the face from the thorax. On Sardinian Neolithic ceramics, figures are depicted with a round head, a long thin neck and an hourglass body. Highly pronounced necks are also characteristic of the Porto Ferro-Monte d'Accoddi marble figurines (Lilliu Reference Lilliu1999).

The torso has a trapezoidal morphology, which is also typical of the Sardinian statuettes of the fourth millennium BC. The pelvis is depicted in a discoid form, like an enlarged replica of the face. This conical torso and round pelvis combination is also found on Ozieri figurines: the legs are never featured, only the upper body (Figure 4). This style can also be observed on some Anatolian and Cycladic figurines, such as those from Beycesultan, Troy and Kusura (Renfrew Reference Renfrew1972).

The ‘orant’ position with outstretched arms is evident from a very early date on ceramics of the Mediterranean Early Neolithic (impressed ware cultures of southern Italy and Iberia). In Sardinia, the Ozieri ceramics also include figures with arms outstretched (Monte Maiore di Thiesi and Sa Ucca di su Tintirriolu) (Figure 4) (Tanda Reference Tanda1985).

The non-engraved stela

This fine-grained granite monolith has a deliberate fracture surface on one side, and on the other a natural surface. It is clear that the block was quarried from the upper levels of the outcrop (Mens Reference Mens2008). The shaping of the stela appears deliberately anthropomorphic (Figure 5) and suggests that it is complete. Red paint survives on the upper part of the stela, and this is currently being analysed.

Figure 5. Non-engraved stela model with exposed ‘head’ area (photograph by F. Leandri).

The stela is 1.27m high, 0.85m at its widest and the depth ranges from 0.10–0.22m. It can be categorised with stelae and menhirs that have been roughly hewn into human form. Examples dating from the fifth millennium BC are found in Brittany, erected in corridor tombs (dolmens A, B and C of tumulus III on Guennoc Island, Landeda, Finistere) or reused to create megalithic tombs (Le Roux Reference Le Roux and Guilaine1998). In various parts of France, menhirs have been fashioned with an ogive-shaped ‘head’. The Yverdon formation (Switzerland) has similarly shaped examples that are attributed to the Middle Neolithic (Voruz Reference Voruz1992).

Discussion

The morphology and motif of stela 1 exclude it from the cultural sphere of the statue menhirs of Corsica. Instead, its small size and trapezoidal morphology resemble pre-statue menhirs and pre-dolmen stelae from the south of France. Its iconography, which is currently unique not only in Corsica, but in the whole Tyrrhenian region, does not facilitate a comparative approach. The constituent parts of its iconography, however, are reminiscent of conventions in the art of various Neolithic cultures on a variety of media, and stela 1 therefore probably dates to the fourth millennium BC. Stela 2 echoes a model known on the continent from the fifth millennium, but which may have known later versions. Sardinian influences in southern Corsica are noted by Bailloud (Reference Bailloud1969), who compared Ozieri ceramics with those of Basi (Serra-di-Ferro). Recent studies confirm the presence of Ozieri influences in southern Corsica (Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Tramoni and Commandré2014). The engraved stela at Balchiria could be considered part of this same movement. As it stands, this stela is unique in the Western Mediterranean context both in terms of its motif and morphology.