Advances in our knowledge and understanding of how psychiatric disorders present in people with learning disabilities, combined with working in dispersed community services and increasing expectations, have contributed to an increase in the workload of learning disability psychiatrists. Both service users and psychiatrists welcome improved detection and treatment of mental illness, but in people with learning disabilities there are some concerns about how able services are to meet this increased workload (Reference McKenzie, Paxton and MathesonMcKenzie et al, 2000).

Piachaud (Reference Piachaud1989) gathered information about the workload of 13 consultants in learning disability psychiatry and from this calculated that, for a population of 200 000, 90 medical hours per week are required (20 for primary care and 70 for specialist care). He recommended that this should be split between two consultants with supporting medical staff. The Royal College of Psychiatrists recommends one consultant in learning disability psychiatry per 100 000 (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1992).

This paper reports information on the learning disability psychiatric staffing levels and how these relate to catchment populations, bed numbers and other professionals, for all learning disability health services in Scotland.

Method

A 13-item questionnaire was developed, based on that used by Bailey & Cooper (Reference Bailey and Cooper1997) for a similar survey of services in England and Wales. It included questions on learning disability health services and staffing levels. This was sent to the chief executive of each of the 13 identified NHS trusts that provide learning disability services and to the general managers of the two health boards that fund services directly in Scotland. The same questionnaire was also sent to the lead clinician/clinical director of each service. A duplicate questionnaire was sent to non-responders after 4 weeks. Results were analysed on 28 June 2000.

Results

A response rate of 100% was achieved because a reply was received from either the manager or lead clinician of each identified service. There are 15 learning disability services in Scotland but one provides a national high-security forensic service only and was excluded from the data analysis. Some respondents provided incomplete information and hence the total sample number reported in the data tables is not always 14. The data are presented in the form of mean, median and range (some of the distributions were skewed, hence the description of medians).

There are 14 local learning disability services in Scotland, all of which provide services for adults with learning disabilities and mental health needs. Four of these services also provide for children with learning disabilities. Three services in Scotland have completed their hospital resettlement programmes and eleven are still in the process of resettlement.

Information was collected on catchment population size and staffing levels. Data on the number of beds and day hospital places currently provided and those planned for post-resettlement were also collected. To facilitate comparisons, the data were converted to the equivalent of whole time equivalent (WTE) consultant within trusts and are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Catchment population and staffing level per whole time equivalent (WTE) consultant per service

| Mean | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catchment population per WTE consultant | 161 140 | 160 000 | 56 000-253 333 |

| Combined training-grade and non-consultant career grade staff per WTE consultant | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0-2 |

| Non-consultant career-grade staff per WTE consultant | 0.58 | 0.65 | 0-1.4 |

| Training-grade staff per WTE consultant | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0-1.33 |

There were 34.5 consultant/senior lecturer posts, 17.5 non-consultant career-grade staff (NCCG) (staff grade, clinical assistant, hospital practitioner, associate specialist) and 23.9 training-grade posts (senior house officer, specialist registrar) in Scotland. Of the consultant/senior lecturer posts, 5.4 (15.6%) were vacant, as were 2 (11.4%) of the NCCG posts and 2 (8.4%) of the training-grade posts.

The range of population served by each consultant in learning disability psychiatry (after adjusting to WTEs) was 56 000-253 333. In addition to consultants, nine services have both NCCG staff and training-grade staff. Two services have one or the other and one service has only consultants among its psychiatric staffing.

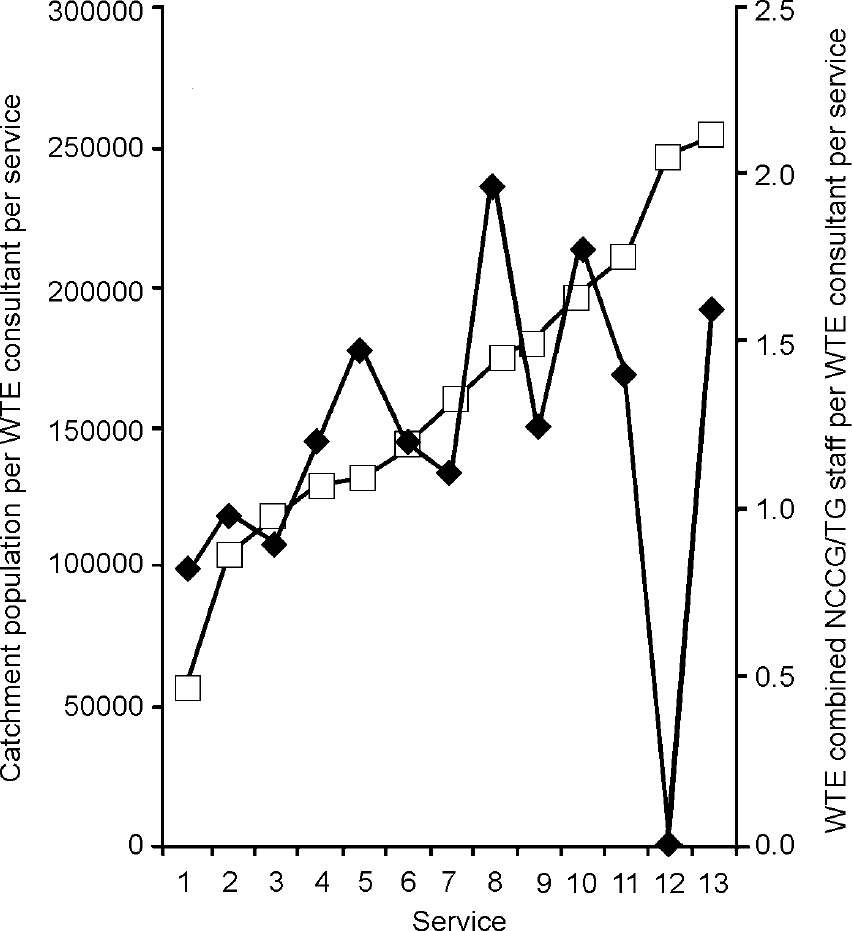

The number of combined training-grade and NCCG psychiatrists per consultant tends to increase as the catchment population per consultant does, except for one particular service (12 in Fig. 1) that has a catchment population per WTE consultant well above the median.

Fig. 1 Catchment population per whole time equivalent (WTE) consultant per service (□) and combined non-consultant career-grade (NCCG)/training-grade (TG) staff per WTE consultant per service (♦)

The three services that have completed resettlement (1, 2 and 6 in Fig. 1) all have catchment populations per WTE consultant less than the median. This is explained by the now widely accepted view that there is an increased need for professionals' time when residents move from hospital to the community (Scottish Executive, 2000). Rural areas (services 1, 2, 9, 11, 12 and 13) tended to have either a much smaller or much larger catchment population per WTE consultant than the median. The smaller numbers are perhaps explained by the acknowledgement of the increased time involved in travelling to the rural areas but the larger numbers are presumably a result of under-resourcing. Rural areas are also much less likely to have any training-grade staff.

The median consultant learning disability psychiatrist per trust in Scotland covers a catchment population of 160 000 and works with 0.65 WTE NCCG staff and 0.68 WTE training-grade staff. They work with 2 WTE psychologists and 4.9 WTE community learning disability nurses.

The current number of beds per service was also converted to number per WTE consultant per service and is presented in Table 2. The number of beds provided by each service varies considerably across Scotland. Those that have completed resettlement have many fewer or no long-stay beds. Some services have considerable day hospital places whereas others have none. Not all services provide forensic or respite care beds.

Table 2. Current beds per whole time equivalent (WTE) consultant per service

| Number of beds per WTE consultant per service | Mean | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment and treatment | 5.0 | 3.7 | 0-12 |

| NHS long stay | 34.2 | 23 | 0-135.5 |

| Rehabilitation | 7.9 | 0 | 0-73.3 |

| Respite | 3.4 | 0.6 | 0-28.3 |

| Forensic | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0-7.5 |

| Day hospital places | 4.6 | 0 | 0-30 |

| Total beds | 52.5 | 49 | 7-139.5 |

| Total bed/day hospital places | 68 | 57.8 | 7-139.5 |

There is a wide range in the number of beds per WTE consultant per service. The median consultant in learning disability in Scotland is currently responsible for 3.7 assessment and treatment beds, 23 long-stay beds, no rehabilitation beds, 0.6 respite beds, 0.7 forensic beds and no day hospital places (a median of 57.8 beds and day hospital places in total). Once resettlement in Scotland is complete, based on the projected figures provided by each service, this will change to substantially fewer long-term beds at six per WTE consultant per service. The other bed types will change little (18 beds and day hospital places in total).

Discussion

There was a response rate of 100% for this survey, which was achieved partly owing to approaching both the chief executive and lead clinician of each service. It may also reflect the current level of interest in learning disability services in Scotland.

This survey shows a wide range in the catchment population covered by each consultant and also in the number of non-consultant psychiatrists and bed/day hospital places they work with. Some, but not all, of this variation is explained by a combination of the resettlement stage, rural/urban differences in service provision and also the age range covered by each service.

One would anticipate that where a consultant provides a service for a catchment population significantly higher than that of his/her colleagues, the consultant with the higher catchment population would work with more NCCG psychiatrists. However, this was not always the case and the distribution of NCCGs is highly variable, with two consultants having none and three services having at least one WTE NCCG psychiatrist per WTE consultant. Three of the six services with a catchment population per consultant above the median did not have above the median level of NCCG staff.

One might assume that lifespan services (services 1, 8, 11 and 12 in Fig. 1) would have either increased staffing levels or a smaller catchment population per WTE consultant when compared with services providing only for adults. However, this was not always the case. Three of the four lifespan services had above the median catchment population per WTE consultant and, although two of these services had above the median number of NCCG staff per WTE consultant, one service had only consultant staff.

This survey highlights the wide range of service provision and staffing levels throughout Scotland. This is partly explained by the fact that so many services are at present undergoing development and modernisation, but it also shows a postcode lottery of resources. Past experience leads us to predict that service developments are not always right first time, but being able to benchmark services and staffing levels against national standards may help to reduce this.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the health services in Scotland who participated in this survey and we wish to thank Mrs Eileen Green for secretarial support.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.