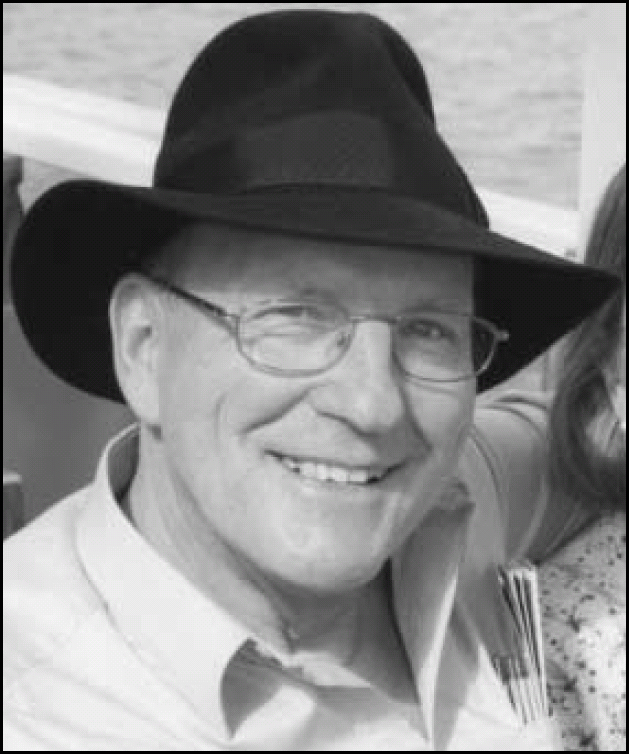

Jim MacKeith (his universal and preferred name is in itself an index of hatred of pomposity) was born on 29 October 1938 at Leamington Spa, the eldest of six children. His family have a long history of distinguished medical practitioners: his grandfather was a doctor and his father, Stephen MacKeith, an eminent psychiatrist, was active in the old Royal Medico-Psychological Association and was the physician-superintendent of Warlingham (Mental) Hospital, Surrey. After the outbreak of the Second World War he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and played a leading role, under Dr J. R. Rees’ directorship, in establishing and running a modern army psychiatric service. He was awarded the OBE for his services. Another prominent figure in Jim's family was Dr Ronald MacKeith, a renowned paediatric consultant at Guys and a well-known medical historian.

Jim also aspired to become a doctor and was sent appropriately to Epsom College, a medical foundation. Sadly, he failed to shine academically, so badly indeed that his poor O and A level results were not good enough to secure him entrance to any of the several medical schools he applied to in the UK. He turned, very wisely as it so happened, to Trinity College, Dublin, to study literature on a flexible degree course that enabled him to undertake medicine later. There he was highly successful and graduated MA, MB, BCh and BAO (Dublin) in 1965. There was an added bonus: living for a number of years in Ireland left Jim with an abiding affection for both the country and the people.

After the completion of the statutory pre-registration house jobs in the UK, he decided to follow in his father's footsteps and make psychiatry his métier. To that end, he began his training at the Middlesex Hospital, London, from where he went to the Maudsley Hospital to work under Peter Scott, a leading forensic psychiatrist. Scott was an impressive figure and an excellent teacher, and it is a fair assumption that he suggested Jim concentrate on forensic psychiatry, a specialty in a somewhat embryonic state in the UK at that time. He found a position at HM Prison in Brixton, London, and later at Broadmoor Hospital, a high secure hospital for convicted offenders with mental health problems. Both institutions offered Jim unique and challenging experience of the probably less attractive aspect of his chosen specialty. So equipped, he was well qualified for his next job as a consultant at the Maudsley and Bethlem Hospitals (1977). His responsibility was to develop new medium-secure facilities in the South East Thames region for the treatment of offenders with mental disorder. Then, in 1985, the Denis Hill Unit was opened at Bethlem, to which Jim was appointed. However, he found an added challenge there as the unit treated both in-patient and out-patient offenders. He met the challenge with his customary panache and he remained there until his retirement in 1999.

However, to really understand Jim's core work, for which he will be ever-remembered, is to appreciate how happily his personality matched the niceties of the work he felt obliged to do. For example, his hatred of pomposity, which has been already illustrated. More importantly, perhaps, was his empathy with the underdog coupled with his abhorrence for injustice which he felt compelled to eradicate even if it meant stamping on the toes of the establishment and, by so doing, endangering his own career.

This compulsion is well highlighted in the late 1970s when Jim became deeply concerned with the cases of convictions arising, he strongly suspected, from false confessions under police interrogation. To investigate this matter, he joined forces with a colleague, an Icelandic psychologist Gisli Gudjonsson (now professor) then at the Institute of Psychiatry in London, and they discovered that in certain cases this was patently so. Their alarming results were published and created a considerable stir at home and abroad. In the UK, with the aid of sympathetic solicitors, steps were taken in certain high profile cases to launch an appeal and in the cases of the Guildford Four (1989), the Birmingham Six (1991) and Judith Ward (1992), for example, the sentences were quashed. In all these cases the successful appeals were based substantially on the findings of Jim's and co-workers’ exhaustive and patient work.

In the aftermath of these momentous events, the Criminal Cases Review Commission was set up in 1997 to investigate claims of miscarriage of justice and Jim MacKeith was appointed as a founder member – the only medical member in fact. Jim's fame was spread far and wide and led, inter alia, to an invitation to act as a specialist adviser for the Council of Europe Committee for the Prevention of Torture, and to serve as the first chairman of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Committee on Human Rights.

A final example of Jim's determination to act, no matter what, in accordance with his beliefs and convictions: he was horrified by the scandal at Guantanamo Bay vis-à-vis British nationals held there. He was subsequently invited to visit the prison but sadly, at that time, his cancer was well advanced, leaving him ill and in pain. Nevertheless, he agreed to go without hesitation. It is a cruel irony that death cheated him of the successful news that the US had agreed to finally repatriate the five UK suspects.

It was only in 2007 that the powers-that-be deigned to award him the OBE. Attached, however, was the very gracious commendation from Mr Jack Straw, the then Minister of Justice – ‘for having changed the landscape in criminal justice and human rights.’

Jim died on 5 August 2007. He died, as he had lived, with exemplary courage. He leaves behind him his widow, Keesje, a daughter, Gwen and two sons, Sam and Piet, both, as might be expected, doctors.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.