Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and policy measures such as lockdown, social distancing, and working or studying at home have had prolonged effects on people’s daily activities, Reference El Keshky, Basyouni and Al Sabban1,Reference Haleem, Javaid and Vaishya2 families, Reference El Keshky, Basyouni and Al Sabban1 culture/traditions or ways of life, Reference Raude3 education, Reference Sintema4 access to healthcare services and infection prevention supplies, Reference Moynihan, Sanders and Michaleff5 the economy, Reference El Keshky, Basyouni and Al Sabban1 and mental health. Reference El Keshky, Basyouni and Al Sabban1,Reference Raude3 A study on the social and cultural impacts of COVID-19 found that the pandemic caused a reduction in daily activities, certain religious activities, and traditional and cultural activities. It also kept friends and family members at a distance, resulting in a lack of social contact. Reference Haleem, Javaid and Vaishya2 In addition, patients, people under quarantine, caregivers, family, friends, and communities were exposed to social stigma due to lack of knowledge about the disease, resulting in paranoia and anxiety in society, social isolation, and a decrease in the solidarity and unity of people in society. Reference Raude6,7 A pilot study in Thailand demonstrated that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and government policies included a decrease in national travel (63.5%), eating out (63.0%), participation in religious, traditional and cultural activities (61.5%), patronage of beauty salons (61.0%), and shopping at the mall (58.0%). Reference Kasatpibal8

A study in Zambia found that the spread of COVID-19 affected the education of students at the high school level. The teachers and students lacked support for online learning. This resulted in a reduction in learning interactions between students and teachers. It also affected the students’ entrance examination scores to higher education. Reference Sintema9 These findings were very similar to the findings of a pilot study in Thailand. Some students reported a delay in graduation (61.0%), did not have devices and accessories needed for online learning (43.0%), had no support for solving problems during online learning (43.0%), had difficulty accessing or had no internet access for online learning (38.5%), and lacked the skills for online learning (38.0%). Reference Kasatpibal8

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the global economy. It resulted in the economic slowdown of countries around the world, including Europe, the Americas, and Asia 10 resulting in a decrease of gross domestic product and economic growth. Reference Sumner, Hoy and Ortiz-Juarez11 It also slowed down the manufacturing of essential goods, disrupted supply chains, led to losses in national and international business, and resulted in poor cash flow for global markets. Reference Haleem, Javaid and Vaishya2 In addition, a report from the US revealed that COVID-19 caused a financial crisis among those with low incomes, with 43.0% of US adults losing their jobs or having their wages cut. As a result, 53.0% of US adults did not have enough funds to cover expenses in the first month after a job loss and only 23.0% expected that they had enough funds to get through a three-month period. Reference Parker, Horowitz and Brown12 Economic experts predicted that the impact could cause 420–580 million people worldwide to enter into poverty. Reference Sumner, Hoy and Ortiz-Juarez11 A study of people in urban slums in Thailand found that 18.9% and 18.0% of working-aged participants were laid off or had reduced working time and income, respectively. Street food vendors could not earn income (18.2%), while those who were self-employed had reduced or no income (18.4%). A majority (60.2%) of the population had vastly decreased income and nearly a third of the population (31.2%) lost about half their income. Less than 10.0% felt little or no economic impact due to earning a fixed salary. Reference Satayanurug, Visetpricha and Pintobtang13

Previous studies have demonstrated that the major impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been psychological leading to increased fear, anxiety, stress, and depression leading to suicide. Reference Ho, Chee and Ho14–Reference Torales, O’Higgins, Castaldelli-Maia and Ventriglio19 A study in China found that the frequency of social media exposure increased the risk of anxiety (OR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.31–2.26) and both depression and anxiety (OR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.52–2.41). Reference Gao, Zheng and Jia20 A pilot study in Thailand found that the participants felt stress after being laid off (63.5%), stress from the fear of being unemployed (62.5%), anxiety about finding a new job (62.0%), anxiety about future layoffs (61.0%), and depression from social isolation (39.0%). Reference Kasatpibal8

COVID-19 and subsequent government policies have affected various aspects of people’s lives. However, few studies have compared the contribution of each. This study aimed to ascertain the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting policy measures.

Methods

Study design and participants

Between October 2020 and January 2021, a cross-sectional study was conducted among 2,500 people living in 5 provinces in Thailand using a stratified sampling method. Participants who lived in Bangkok, Chonburi, Chiang Mai, Nakhon Ratchasima, and Yala provinces were selected because they experienced a notable surge in COVID-19 cases in each region during the study timeframe. All participants were at least 18 years of age, able to communicate in the Thai language, and were willing to cooperate with this study. Persons who were critically ill during the study period or who could not provide information for this study were excluded.

Ethical considerations

The Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Nursing, Chiang Mai University (reference no. 105-2020) approved this study. Before signing an informed consent form, participants were made aware of the study’s objectives, procedures, and benefits. Data collection began only after participants had given their consent. Each participant’s identity was kept confidential.

Instrument

The researchers developed a questionnaire as the research instrument, which underwent a thorough review to establish a clear theoretical framework for each impact domain. Two research consultants provided feedback, leading to reorganization of impact classification into 7 aspects. Following this, six experts assessed construct validity, ensuring face validity through a Zoom meeting where wording in some questions was revised. Pilot testing with 15 samples gathered feedback on question clarity, relevance, and appropriateness, leading to further refinement based on input from experts and the pilot testing.

The content validity index of the impact of the COVID-19 questionnaire was 1.00 and the reliabilities of the impact of the COVID-19 questionnaire and the depression anxiety stress questionnaire (DASS-21) translated into the Thai language DASS-21] Reference Oei, Sawang, Goh and Mukhtar21 were 0.84 and 0.83, respectively.

The questionnaire consists of three parts. Part 1: demographic information that included the province, age, gender, occupation, education level, religion, income, and level of compensation from the government. Part 2: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (the consequences of the spread of SARS-CoV-2) and policy measures (the consequences of the actions taken by governments, ministry of public health, and other organizations to mitigate the spread of COVID-19) questionnaire with a total of 48 items on a 4-point rating scale with responses of none (1 point), low (2 points), moderate (3 points), and high (4 points). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy measures was classified into 7 aspects including people’s daily activities, family, cultural/traditional or community ways of life, education, infection prevention and access to healthcare, economy, and mental health. The total impact score was further divided into 3 levels: low, moderate, and high. Part 3: the depression anxiety stress questionnaire asks the individual to indicate the presence of a symptom over the previous week. This questionnaire had a total of 21 items on a 4-point rating scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time) and was designed to measure the severity of a range of symptoms common to depression, anxiety, and stress. Responses were classified into 5 levels including normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe.

Data collection

Village health volunteers distributed the questionnaire to 500 participants living in each of 5 provinces for a total of 2,500 participants. The response rate was 100%.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using R version 3.5.1. Frequency and percentage, mean and standard deviation, and median and range were calculated for demographic data, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and policy measures data as appropriate. Factor loadings in confirmatory factor analysis were performed and T-statistics were used to test the overall weighted mean difference between the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak and policy measures and the differences in each province. The level of significance was set at p < .05.

Results

Demographics

Most participants were female (71.6%), laborers (34.6%), and had a mean age of 43.4 ± 14.4 years. Most participants identified as Buddhist (78.0%). A majority of participants held a primary- or secondary-level education (35.2% and 34.0%, respectively). Most of them had mid-level incomes (83.7%). Most participants received compensation from the government (59.0%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Participant demographics (n = 2,500)

Level of impact on COVID-19 from the pandemic and policy measures

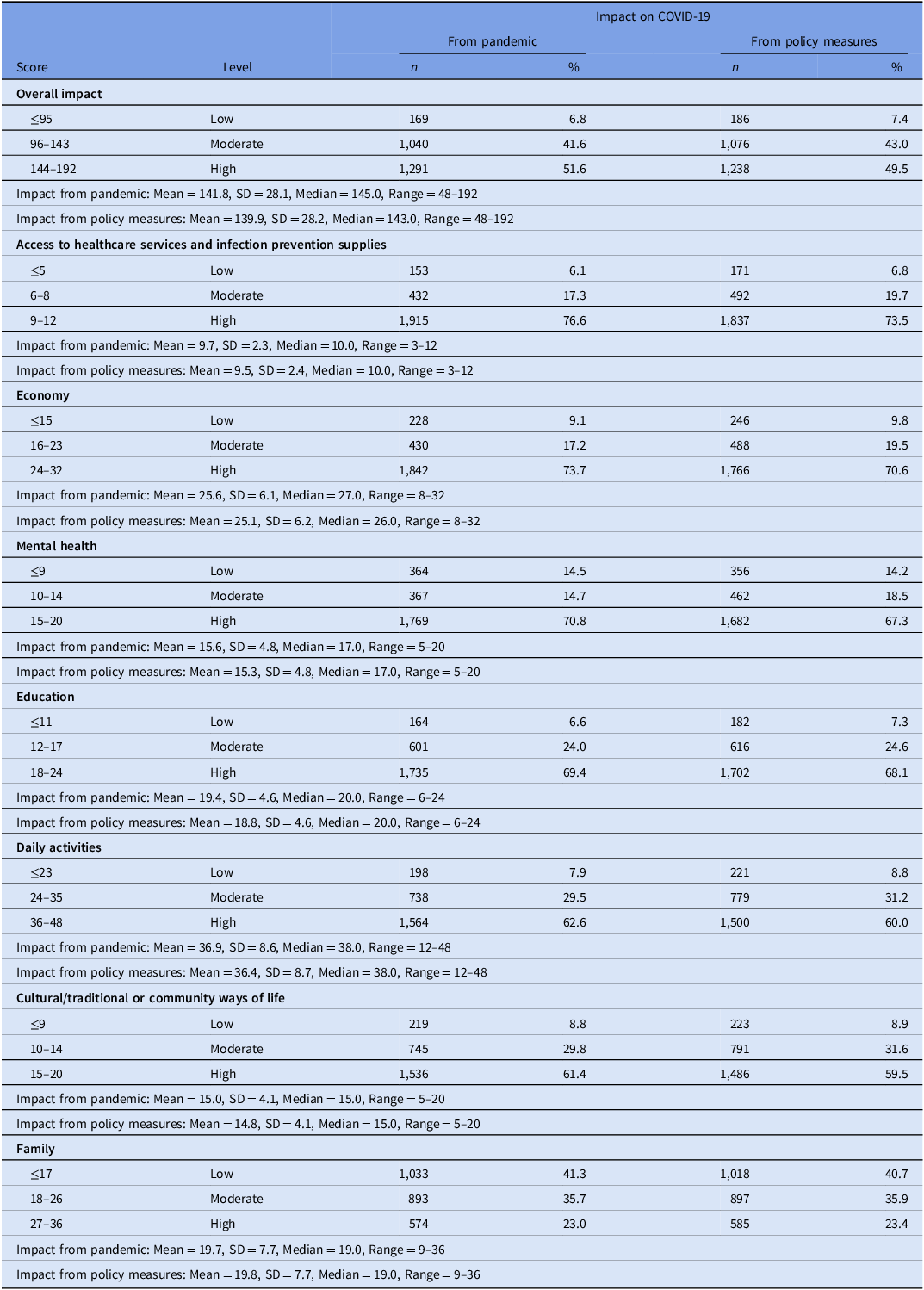

Overall, participants reported a high level of impact from the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting policy measures (51.6% and 49.5%, respectively). The top five categories that were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the policy measures implemented were access to healthcare services and infection prevention supplies (76.6% vs 73.5%), economy (73.7% vs 70.6%), mental health (70.8% vs 67.3%), education (69.4% vs 68.1%), and people’s daily activities (62.6% vs 60.0%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Level of impact of COVID-19 from the pandemic and policy measures among participants (n = 2,500)

Impact on COVID-19 from the pandemic and policy measures

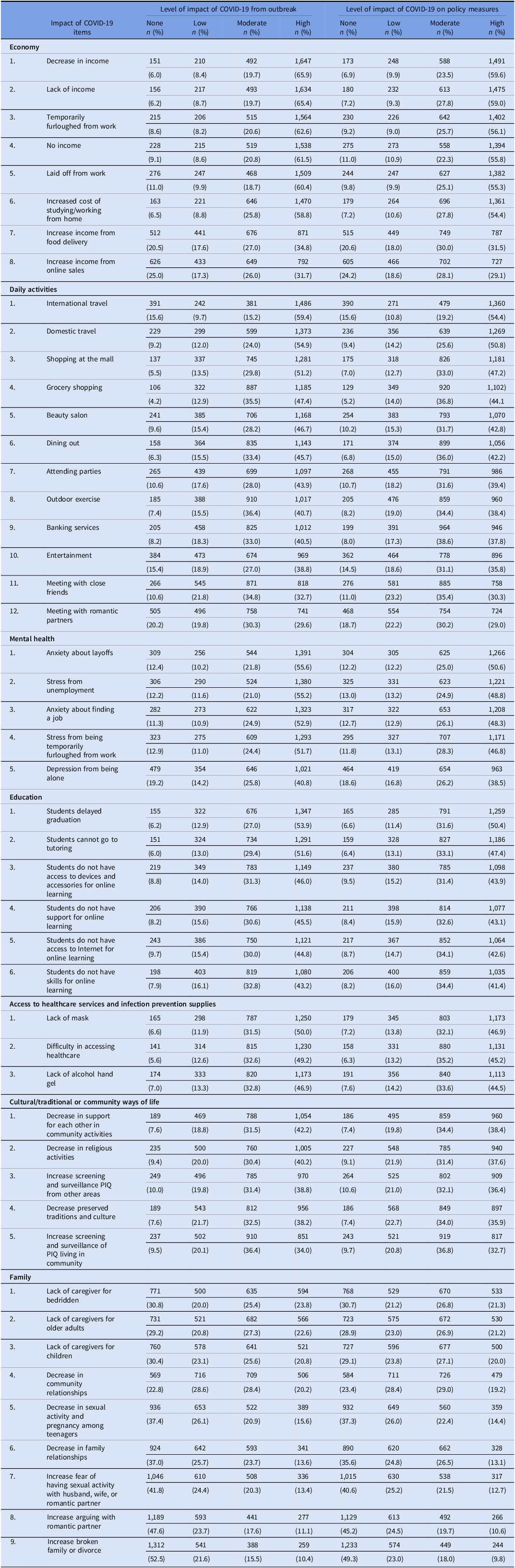

The top five categories impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and policy measures were the economy including a decrease in income (65.9% vs 59.6%), insufficient income (65.4% vs 59.0%), temporary furlough from work (62.6% vs 56.1%), loss of income 61.5% vs 55.3%), and layoffs from work (60.4% vs 59.8%). These were followed by the impact on their daily activities including decreased international travel (59.4% vs 54.4%), decreased domestic travel (54.9% vs 50.8%), and decreased shopping at the mall (51.2% vs 47.2%) (Table 3).

Table 3. Response to impact of COVID-19 from outbreak and policy measures items among participants (n = 2,500)

Level of anxiety, stress, and depression from the COVID-19 pandemic

Some participants reported extremely severe anxiety (11.0%), extremely severe stress (4.2%), and extremely severe depression (6.3%) from the COVID-19 outbreak (Table 4).

Table 4. Level of anxiety, stress, and depression from the COVID-19 pandemic among participants (n = 2,500)

Comparing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic to policy measures

The weighted effect of the impact of COVID-19 was statistically (p < .001) greater than that of governmental policy measures on family (0.664 vs 0.618), education (0.562 vs 0.557), and economy (0.643 vs 0.572). The weighted effect of the impact from governmental policy measures was statistically (p < .001) greater than that of COVID-19 on daily activities (0.675 vs 0.651), cultural/traditional or community ways of life (0.769 vs 0.736), access to healthcare services and infection prevention supplies (0.410 vs 0.390), and mental health (0.625 vs 0.584) (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of the weighted effect of impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy measures among participants

* Weighted effect of impact from policy measures was presented in parenthesis.

Discussion

This study achieved a 100% response rate. This may be because this study attributes its success to a clear and concise questionnaire, pre-testing for construct and face validity, and effective communication by researchers emphasizing the survey’s benefits, confidentiality, and anonymity. Accessibility was ensured by 7 researchers and 125 health volunteers visiting participants’ homes, allowing for immediate completion or within 2 weeks at the participants’ convenience. Incentives of 100 baht (approximately three dollars) for participants were offered.

This study found that about half of the participants felt the effects of COVID-19 and subsequent governmental policy measures affected them at the highest level. The weighted effects of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy measures were different.

More than 60.0% of participants felt the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the policy measures were the most profound, including a decrease in income, being furloughed from work, or being unemployed. The findings are consistent with global reports 10,Reference Sumner, Hoy and Ortiz-Juarez11 and studies from the US Reference Parker, Horowitz and Brown12 and Thailand. Reference Sumner, Hoy and Ortiz-Juarez11,Reference Satayanurug, Visetpricha and Pintobtang13,22

The impact from the COVID-19 pandemic and policy measures had significant effects on people’s daily activities including international travel, domestic travel, shopping at the mall, grocery shopping, visits to beauty salons, dining out, attending parties, outdoor exercise, visiting banks, entertainment, meeting close friends, and meeting romantic partners. These findings are congruent with systematic reviews Reference El Keshky, Basyouni and Al Sabban1,Reference Haleem, Javaid and Vaishya2 and studies from Turkey Reference Ali, Yilmaz, Fareed, Shahzad and Ahmad23 and the US. Reference Giuntella, Hyde, Saccardo and Sadoff24

Some participants in this study also had psychological problems including anxiety about layoffs, stress from unemployment, anxiety about finding a job, stress from being temporarily furloughed from work, and depression from being alone. This is similar to findings from studies conducted in the US, Reference Giuntella, Hyde, Saccardo and Sadoff24 Spain, Reference Rodríguez-Rey, Garrido-Hernansaiz and Collado25 Italy, Reference Saladino, Algeri and Auriemma26 and Thailand. Reference Kasatpibal8,Reference Apisarnthanarak, Siripraparat and Apisarnthanarak16,Reference Thatrimontrichai, Weber and Apisarnthanarak27–Reference Apisarnthanarak, Apisarnthanarak, Siripraparat, Saengaram, Leeprechanon and Weber29

This study also found that some participants had problems related to their education including delays in their graduation, not being able to attend tutoring, not having access to devices and accessories for online learning, lack of support for online learning, lack of Internet access for online learning, and lack of skills for online learning. This is congruent to findings from studies in Spain, Reference Sintema4 Saudi Arabia, Reference Alghamdi30 and Thailand. Reference Kasatpibal8

Participants in this study also reported problems with access to healthcare services, which was similar to studies from Chile, Reference Núñez, Sreeganga and Ramaprasad31 Nigeria, Reference Okereke, Ukor and Adebisi32 and Thailand. Reference Kasatpibal8

In addition, this study found that participants had difficulty accessing infection prevention supplies due to a shortage of masks Reference Ji, Fan, Li and Ramakrishna33,Reference Kampf, Scheithauer, Lemmen, Saliou and Suchomel34 and alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Reference Kampf, Scheithauer, Lemmen, Saliou and Suchomel34

Some participants in this study had issues with cultural/traditional or community ways of life including decreased support for each other in community activities, decreased religious activities, increased screening and surveillance of people in quarantine (PIQ) from other areas, inability to practice traditions and culture, and increased screening and surveillance of PIQ living in the community. This is on par with studies from the WHO, 7 France, Reference Raude3,Reference Raude6 Ghana, Reference Osei-Tutu, Affram, Mensah-Sarbah, Dzokoto and Adams35 and Thailand. Reference Kasatpibal8

Participants in this study also experienced familial problems including lack of caregivers for bedridden family members, older adults, and children; a decrease in community relationships; a decrease in sexual activity and pregnancy among teenagers; a decrease in family relationships; fear of engaging in sexual activities with a spouse or romantic partner; arguments with a romantic partner; and having a broken family or divorce. These findings are congruent with one systematic review Reference Alghamdi30 and another study done in Thailand. Reference Kasatpibal8

As determined by this study, the overall weighted effects of the impact of COVID-19 and policy measures were statistically different. The strength of this effect varies among different categories. In the case of being affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, people in urban areas, such as Bangkok and Chonburi, were affected by changes in education more than other categories, which further affected the economy. This is due to the fact that parents have to take time off work to take care of their children attending school online at home. On the other hand, people in rural areas such as Chiang Mai, Nakhon Ratchasima, and Yala found that their cultural/traditional or community ways of life and daily activities were impacted more than other categories. The policy measures affected the economy and mental health as reported by people in urban areas, including Bangkok and Chonburi. People in rural areas, including Chiang Mai, Nakhon Ratchasima, and Yala, reported that daily activities remained an important aspect of their lives. People in Nakhon Ratchasima and Yala reported that cultural/traditional or community ways of life were of higher importance than other categories, which was different from Chiang Mai where access to healthcare services and infection prevention supplies were most important.

The impact on cultural/traditional or community ways of life and daily activities led to reduced interactions within the community and changed the social norms of people who lived in rural areas and usually had close relationships. The economic and psychological impacts result in a reduced quality of life and, in some cases, may lead to suicide.

This study’s findings can be used to develop policies or other methods to reduce the impact of future pandemics on the population. They can also be used as a guide when looking at the severity of aspects of the impact of COVID-19 and policy measures, especially in urban and rural areas where impacts are different depending on peoples’ lifestyles, cultural/traditional or community ways of life, and social norms. Policymakers should develop strategies to provide appropriate support based on how the categories are affected in specific areas (rural vs. urban). If the dominant impact is caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the government should focus on reducing the spread of COVID-19 and decreasing the incidence of new cases. If the dominant impact is caused by policy measures, especially the country lockdown by which people were hit hardest, the government should focus on changing policies as appropriate based on the prevalence of COVID-19 and ensuring the balance of the 7 categories, especially the economy, daily activities, and cultural/traditional or community ways of life. Information from this study can be used to devise policies in accordance with the dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic. The government should change policies and adopt measures appropriately to the pandemic situation and balance these measures with other goals such as the economy, education, and way of life. The government should adopt disease control measures based on risk areas instead of implementing a comprehensive lockdown of the entire country.

Based on our literature review and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has looked at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and compared the impact of the pandemic and government policy measures. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy measures are interconnected, as the latter are responses to the challenges posed by the pandemic, yet they also have distinct characteristics and implications. Recognizing the dynamic of the pandemic and policy effectiveness is crucial, as it makes identifying and comparing their actual effects challenging. Researchers addressed this complexity by explaining impact definitions to participants before questionnaire completion, allowing time for questions and answers.

The results of this study are strengthened by it being a multi-site study with a large sample size and geographic and demographic variability in Thailand. It is important to recognize that individuals within these regions may not be representative of all Thai citizens. The limitation, however, is that it used a self-reported questionnaire which may lead to information bias. This was mitigated by the high content validity of the questionnaire as well as informing all participants about the importance of accuracy when responding to the questions.

Conclusion

About half of the participants in this study felt that the impacts of COVID-19 and the resulting governmental policy measures affected their lives. However, the weighted effect of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the policy measures affected areas and categories differently. More than 60% of participants felt that the economic impact of COVID-19 and the policy measures were the most profound, leading to a decrease in income, lack of income, being temporarily furloughed from work, or being unemployed. Based on this study, we recommend that the government should change policies and adopt measures appropriately to the pandemic situation to ensure that there is a balance with other goals. The government should provide widespread support to reduce the impacts of the pandemic and people’s suffering.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Emeritus Dr. Mingsarn Kaosa-ard for her recommendations and assistance.

Authors contribution

The project was conceptualized and designed by the authors. NK: Data collection, data analysis, and writing original draft. NV: Data collection, data analysis, and assisting in writing original draft. AU: Data analysis and supervision. KT, KK, SS, RT, SA: Data collection. AA: Supervision. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was funded by the National Research Council of Thailand under KHONTHAI 4.0 Spearhead Program. This research work was partially supported by Chiang Mai University.

Competing interests

No conflict of interest to declare.