1. INTRODUCTION

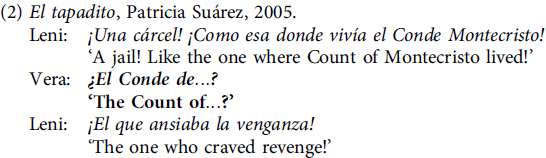

This article aims at describing the usage of partial interrogatives without wh in French and Spanish, a construction that has not yet received much attention in the literature up to date. This construction is formed by simply leaving out an utterance-final element in an otherwise complete utterance. In written texts, the apparent ellipsis of the element is typically represented by three dots, followed by a question mark (see 1-2).

In this article, I will call partial interrogatives without wh-element in-situ-Ø-interrogatives. Only sporadic mention of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives is made in the literature, where such constructions have been called complementary questions (Bolinger, Reference Bolinger1957: 7; Reinhardt, Reference Reinhardt2019: 32), or designedly incomplete utterances that realize fill-in-the-blank questions (Persson, Reference Persson2017).

Formally, in-situ-Ø-interrogatives resemble in-situ-wh-interrogatives (see 3), the only difference being that in in-situ-Ø-interrogatives the wh-element is not present. The invented cases in (3) seem compatible with the usage contexts in (1) and (2), respectively. Consequently, a second aim of this article is to investigate whether we can assume the existence of structured variation (Weinreich et al., Reference Weinreich, Labov, Herzog, Lehmann and Malkiel1968: 101) between in-situ-Ø- and in-situ-wh-interrogatives in French and Spanish. Answering this question will help responding to a major problem raised by acknowledging the existence of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives, namely the question why languages possess wh-elements at all.

In order to establish a description of the usage of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives, a corpus study of the usage of these constructions in French and Spanish spoken informal conversations is carried out. The analysis demonstrates that in-situ-Ø-interrogatives are typically anaphorical and display structural latency (Auer, Reference Auer2014: 14-18). Regarding their function, in-situ-Ø-interrogatives can be used as repair initiators or ‘true’ information requests, just like in-situ-wh-interrogatives. The main difference to in-situ-wh-interrogatives seems to be that in-situ-Ø-interrogatives display an even higher degree of anaphoricity and answerability. As a result, in-situ-Ø-interrogatives realize particularly efficient requests for information because of (a) their minimal syntactic structure and (b) the fact that their use is more likely to lead to a response on the hearer’s part than the use of other interrogative constructions. In line with this interpretation, the use of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives is frequent in contexts centered around efficient information exchange, such as professional telephone calls, teaching contexts and professional explanations.

The second part of the paper addresses the question of the existence of structured variation between in-situ-Ø- and in-situ-wh-interrogatives. Given that in-situ-wh-interrogatives are conventionalized to a greater degree in French than in Spanish, I hypothesize that French speakers prefer this interrogative format over in-situ-Ø-interrogatives, while this preference is expected to be weaker for Spanish. Indeed, results from a questionnaire study demonstrate that when faced with the choice between in-situ-Ø- and in-situ-wh-interrogatives, Spanish speakers are more likely to select in-situ-Ø-interrogatives over in-situ-wh-interrogatives than French speakers. These results suggest that whereas in-situ-Ø-interrogatives represent an ad-hoc strategy for the expression of information requests that may be universal, the usage of in-situ-wh-interrogatives is more restricted.

2. INFORMATION REQUESTS AND ANAPHORICITY

Conversation Analysis distinguishes between interrogatives (a certain type of syntactic format) and information requests, the act of requesting information (Steensig and Drew, Reference Steensig and Drew2008; Hayano, Reference Hayano2013; Ehmer and Rosemeyer, Reference Ehmer and Rosemeyer2018). Although this correlation is in no way absolute (see, e.g., Dekhissi, Reference Dekhissi2016; Reference Dekhissi2021), information requests are typically realized using interrogatives. This preference is easiest to explain for wh-interrogatives, which incorporate a semantically underspecified form, the wh-element. The meaning of a sentence such as Where did you go? can be described as the set of propositions that count as answers to that question, such as <I went to London; I went to Rio, etc.> (Hamblin, Reference Hamblin1973: 48; Karttunen, Reference Karttunen1977: 9-11; or the more recent description in Onea and Zimmermann, Reference Onea, Zimmermann, von Heusinger, Onea and Zimmermann2019: 12). An interrogative thus establishes a set of possible propositions, out of which the hearer is expected to choose the correct one. This instruction to choose the correct possible answer is clearly a pragmatic phenomenon. When using a wh-interrogative the speaker presents herself “incapable, in a particular way, of completing a proposition” (Fiengo, Reference Fiengo2009: 47; cf. also Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2018b; Ozerov, Reference Ozerov2019). The preference for an answer as the hearer’s reaction, as well as the fact that interrogatives frequently select the hearer in terms of turn-taking, can be derived from this formal incompleteness of interrogatives: by highlighting her inability to complete the proposition, the speaker may invite the hearer to complete the proposition for her. As is well known in Conversation Analysis, this pragmatic process is crucially governed by the degree to which the hearer can be assumed to be more knowledgeable than the speaker (Heritage, Reference Heritage, Freed and Ehrlich2010: 140-142; Bolden and Robinson, Reference Bolden and Robinson2011; Enfield et al., Reference Enfield, Brown, De Ruiter and De Ruiter2012: 193-194; Heritage, Reference Heritage2012; Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2022). For instance, an interrogative such as Am I the president? can be interpreted either as a rhetorical question or an actual information request, depending on the degree to which the epistemic gradient between the speakers is tilted.

Crucially for our purposes, this pragmatic theory of the use of interrogatives explains how in-situ-Ø-interrogatives can be interpreted as information requests: just like “regular” wh-interrogatives, in-situ-Ø-interrogatives incorporate a semantically underspecified form, namely, a pause. From this perspective, the main difference between the two invented examples in (4) resides in the fact that the in-situ-wh-interrogative in (4a) specifies the semantics of the requested element (i.e., where refers to a location), whereas (4b) does not. At this point, it is important to note that none of the constructions in (4) is formally a declarative. For in-situ-wh-interrogatives, this option is excluded due to the presence of the wh-element. In-situ-Ø-interrogatives, in contrast, cannot be interpreted as a declarative because their prosodic contour sets them apart from declaratives (see Section 3).

This difference between in-situ and in-situ-Ø-interrogatives relates to an important parameter in the description of interrogatives, namely, context sensitivity, understood here as the degree of cognitive accessibility of the proposition (Dryer, Reference Dryer1996). Many studies have identified context sensitivity as a crucial predictor of the variation between ex-situ- and in-situ-wh-interrogatives. In-situ-wh-interrogatives are typically used in contexts in which the proposition can be inferred from the preceding co-text or the situational context, whereas the usage of ex-situ interrogatives (such as Where have you gone?) is much less restricted in this regard (for French and Spanish, cf. Chang, Reference Chang1997; Cheng and Rooryck, Reference Cheng and Rooryck2000; Mathieu, Reference Mathieu2004; Myers, Reference Myers2007; Boucher, Reference Boucher, Breul and Göbbel2010; Hamlaoui, Reference Hamlaoui2011; Kaiser and Quaglia, Reference Kaiser, Quaglia, Brandner, Czypionka, Freitag and Trotzke2015; Chernova, Reference Chernova2017; Biezma, Reference Biezma, Berns, Jacobs and Nouveau2018; Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2018b; Larrivée, Reference Larrivée, Feldhausen, Elsig, Kuchenbrandt and Neuhaus2019; Garassino, Reference Garassino2022). In Spanish, the use of in-situ-wh-interrogatives is typically infelicitous in “New Topic information requests” (Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2018b; Reference Rosemeyer2022), which serve to establish a new topic in a conversation (5a).

Note that the French equivalent in (5b) seems much more acceptable. Indeed, in a recent corpus-based study, Garassino (Reference Garassino2022) showed that French in-situ-wh-interrogatives are governed to a lesser degree by the degree of cognitive accessibility of the proposition than Italian in-situ-wh-interrogatives, which behave much more like their Spanish counterparts. This result hints at a historical process by which in-situ-wh-interrogatives have entered into competition with ex-situ wh-interrogatives and gradually left their original functional niche (cf. also Larrivée, Reference Larrivée, Feldhausen, Elsig, Kuchenbrandt and Neuhaus2019; Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2019a; b; Guryev and Larrivée, Reference Guryev and Larrivée2021 for historical evidence for such a process in French and Brazilian Portuguese). However, even in contemporary informal spoken French in-situ-wh-interrogatives are still typically used in situations in which their propositions either repeat material from the preceding co-text or can be inferred from a previous proposition (Garassino, Reference Garassino2022).

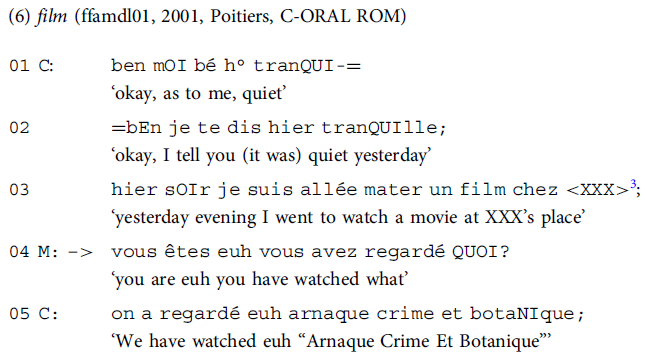

From an interactional perspective, one important correlate of context sensitivity is answerability. As was shown by Myers (Reference Myers2007), French information-requesting in-situ-wh-interrogatives are typically used in contexts in which there is a strong expectation that the hearer knows the answer to the question.Footnote 1 This result was replicated for Spanish (Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2018a). This is due to the fact that if the proposition of an interrogative is highly accessible, it is likely to be part of the interlocutors’ Common Ground, i.e., represent shared knowledge (Stalnaker, Reference Stalnaker1973; Clark, Reference Clark1996: ch. 4; Stalnaker, Reference Stalnaker2002). In that case, however, it is equally more likely for the hearer to know the answer to the information request. Consider, for instance, example (6) below, taken from an informal friendly conversation at home.Footnote 2 M has asked C to tell her what she did on the weekend. In lines 1-2 C asserts that she had a quiet day yesterday and adds in line 3 that she went to visit a friend to watch a movie. M reacts to this information with the in-situ-wh-interrogative in line 4. The interrogative is used to ask which movie C and her friend watched. In line 5, C supplies the requested information.

In (6) the proposition ‘C and her friend watched X yesterday’ of the in-situ-wh-interrogative in l. 4 is considered Common Ground on the basis of C’s recent assertion of this proposition in l. 3. Consequently, M’s interrogative is used to request more information about this event, elaborating the current conversational topic (see Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2018b). In addition, M’s confidence that C believes in the veracity of the proposition also leads to the strong expectation that C can answer her question. Put simply, if C did indeed watch a movie yesterday, she is very likely to know which movie it was.

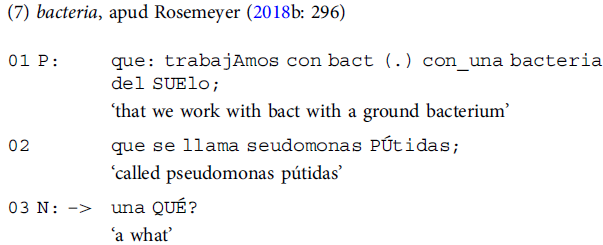

Another important correlate of context sensitivity is anaphoricity. Studies have shown that in Spanish, the use of in-situ-wh-interrogatives is more acceptable when prefaced with conjunctions such as y ‘and’ (Biezma, Reference Biezma, Berns, Jacobs and Nouveau2018) and insubordinating que ‘that’ (Rosemeyer and Sansiñena, Reference Rosemeyer and Sol Sansiñena2019), which serve as cohesive devices connecting the interrogative to the previous co-text. Furthermore, in-situ-wh-interrogatives frequently display structural latency (Auer, Reference Auer2014: 14-18): they can be formally incomplete, which is why the hearer has to reconstruct their complete syntactic structure from the previous context. For example, in order to process the interrogative una qué in (7), the hearer needs to complete the utterance to ¿trabajáis con una qué? ‘you work with what?’, using the previous utterance by P. The resulting full utterance repeats part of the previous context.Footnote 4

From the theoretical premises established in this section, at least three hypotheses regarding the use of French and Spanish in-situ-Ø-interrogatives can be derived. First, in line with my intuition that in-situ and in-situ-Ø-interrogatives express similar situated meanings (Linell, Reference Linell2009), we would expect both constructional types to display high degrees of context sensitivity, which can be measured in terms of answerability and anaphoricity. Second, given that in-situ-Ø-interrogatives are less specific than in-situ-wh-interrogatives in terms of the requested information, we would expect in-situ-Ø-interrogatives to display even higher context sensitivity than in-situ-wh-interrogatives. Indeed, Persson (Reference Persson2017: 236) suggests that “DIUs [=designedly incomplete utterances, MR] are an apt resource for subsequently narrowing down the (“already-relevant”) information sought”.

Third, whereas in French in-situ-wh-interrogatives have undergone a routinization process by which their use is tied to a lesser degree to contexts in which the speaker has good evidence for the assumption that the proposition of the interrogative is shared knowledge and the hearer is in a position to answer the interrogative, no such process seems to have taken place for Spanish.Footnote 5 In addition, there is little evidence for a similar conventionalization process for in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in either language.Footnote 6 In other words, I describe the use of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives as an ad-hoc strategy for realizing information requests that are strongly dependent on the immediate preceding context. If in-situ and in-situ-Ø-interrogatives do indeed compete for the expression of similar meanings in these languages, we can consequently assume that French speakers clearly prefer the use of in-situ-wh-interrogatives over in-situ-Ø-interrogatives, whereas such a preference is much less clear for Spanish speakers.

3. CORPUS STUDY

To test these hypotheses, both a corpus and a questionnaire study were realized. In a first step, all tokens of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives were extracted from the French and Spanish sections of the C-ORAL ROM, a reference corpus of spoken Romance languages (Cresti and Moneglia, Reference Cresti and Moneglia2005). The choice of this corpus was motivated by several factors. First, the use of in-situ-wh-interrogatives has already been studied in this corpus for French (Garassino, Reference Garassino2022) and Spanish (Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2018b). The existence of these previous studies allows for a comparative analysis of the two interrogative constructions. Second, the C-ORAL ROM contains data representing various registers and situations. For instance, the corpus also contains telephone conversations, which will turn out to be important for the analysis. Taken together, the corpus contains n = 194 recordings for French and n = 210 recordings for Spanish, of varying length and word count. Each sub-corpus of the C-ORAL ROM totals about 300,000 words (Moneglia, Reference Moneglia2005: 1).

The in-situ-Ø interrogatives were extracted by manually analysing all turn breaks in the corpus. While I cannot exclude the possibility that in-situ-Ø-interrogatives are sometimes used in turn-medial position, in such a context in-situ-Ø-interrogatives would frequently be virtually indistinguishable from interrupted assertions not only to the analyzing linguist, but also to the interlocutor. Consider the invented example in (8), where the string And you bought… could in principle be interpreted as a in-situ-Ø-interrogative. However, when followed by another utterance, an information request interpretation is disfavoured. It stands to reason that even if an information request reading is intended in (8), such uses are marginal because they would contradict the speaker’s intention to obtain the missing information.

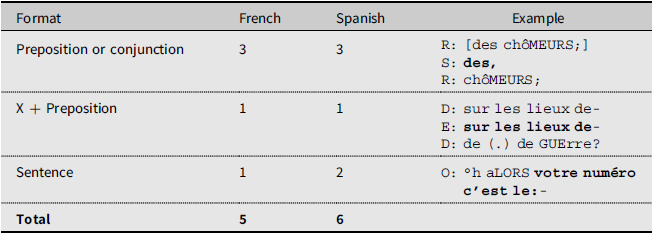

Inspection of the syntactic formats and usage frequencies of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in Table 1 reveals the low productivity of this construction. In the entire corpus, only n = 11 tokens of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives were found. N = 8 of these constructions are syntactically extremely reduced, relying on structural latency; in a in-situ-Ø-interrogatives such as des-, both the syntax and the proposition of the interrogative have to be reconstructed from the preceding context. Only n = 3 cases of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives were found in which the interrogative is syntactically independent from the preceding context. My data revealed no evidence for a significant difference between French and Spanish regarding the usage frequency of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives.

Table 1. Syntactic formats and usage frequencies of French and Spanish in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in the C-ORAL ROM

Another interesting formal aspect concerns the type of interrogative pronoun or adverb that is left unexpressed. For all examples, if the in-situ-Ø-interrogative were to be paraphrased with an in-situ-interrogative, the pronouns quoi/qué would have to be used. In contrast, both in French and Spanish in-situ-interrogatives can be used with a variety of interrogative pronouns and adverbs, although the use of quoi/qué is most frequent (see Garassino Reference Garassino2022: 38).

Both for French and Spanish, the usage frequency of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives is surprisingly high in private telephone conversations. While private telephone conversations only make up 13 percent of the French corpus (26/196 recordings) and 5 percent of the Spanish corpus (11/201 recordings), with n = 4 tokens more than half of the in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in the C-ORAL ROM are found in these data. My qualitative analysis will suggest a reason for this unexpected correlation. It is also worth mentioning that n = 4 tokens of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives were found in teaching or professional explanation contexts, which in this corpus are rather monological in nature.

In the only previous study that explicitly focuses on the analysis of French in-situ-Ø-interrogatives, Persson (Reference Persson2017) distinguished two functions of this construction in interaction, namely repair initiation (Persson, Reference Persson2017: 239-240) and open-ended information requests (Persson, Reference Persson2017: 241-245), and demonstrated that these functions are correlated with differences in prosodic contour. In particular, repair initiation in-situ-Ø-interrogatives are characterized by a rise-from-low contour (L* H%) (Reinhardt, Reference Reinhardt2019: 32; Persson, Reference Persson2020: 591), whereas in open-ended information requests we typically find “more-than-typical lengthening of the utterance-final vowel sound in the last syllable” and a falling contour (Persson, Reference Persson2017: 241). This generalization appears to hold for my data, as well.

However, my corpus study will show that in order to adequately describe the degree of context sensitivity of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives, as well as their relationship to the use of in-situ-wh interrogatives, it is necessary to take into account more situated meanings. In particular, results from previous studies on the situated meanings of in-situ-wh-interrogatives in spoken language (Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2018b; Garassino, Reference Garassino2022) suggest that it is necessary to pay closer attention to Persson’s category of open-ended information requests. These information requests differ in terms of their degree of context sensitivity, which in turn impacts their situated meanings.

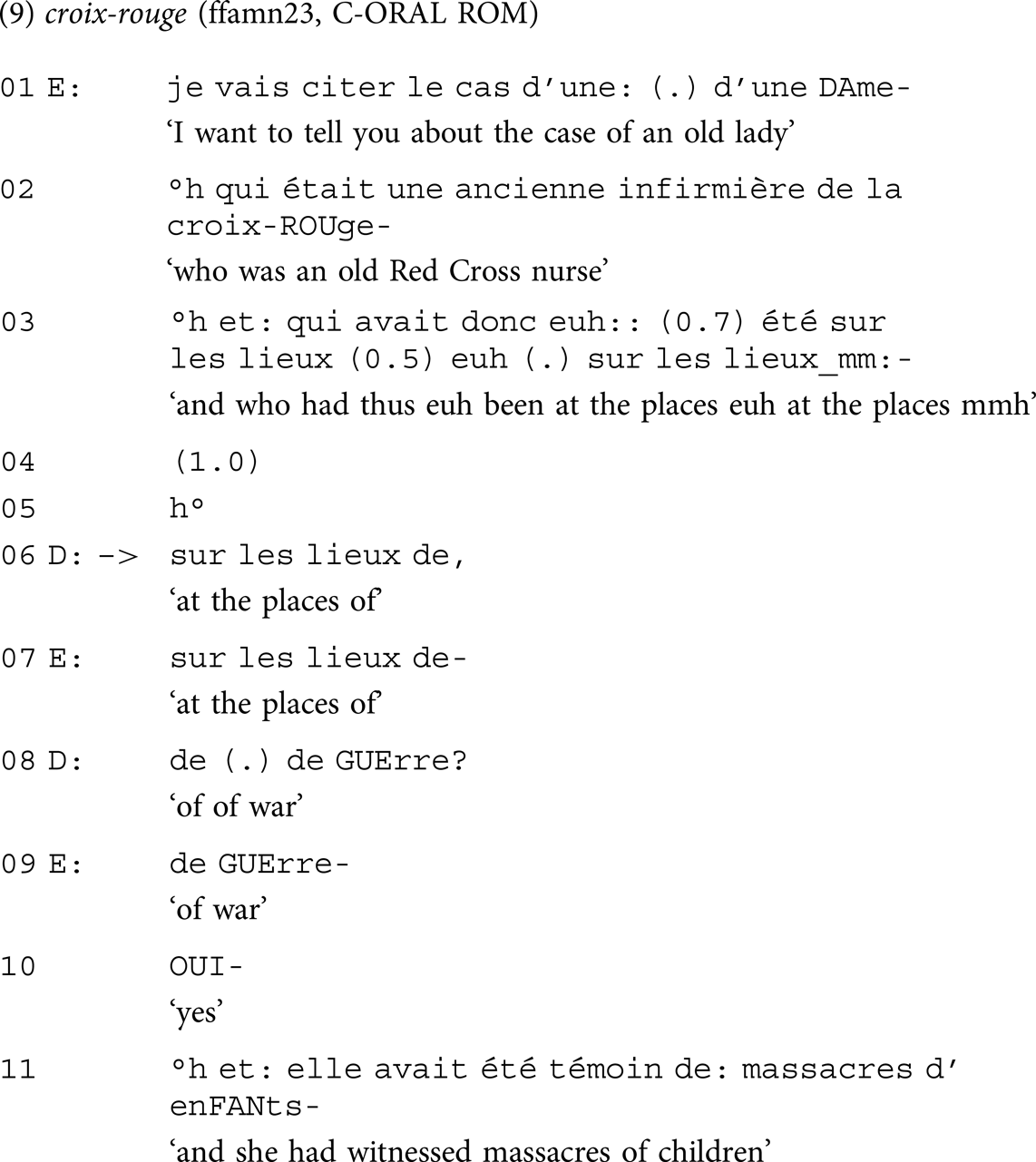

The transcript in (9) exemplifies the first function of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives, which was already identified by Persson (Reference Persson2017), namely repair initiation. In Persson’s (2017: 239) words, repair initiation requests “completion of the bit of talk that was begun”. The participant E is describing her work at the hospital to the interviewer D and has just mentioned how Alzheimer patients are special. In l. 1-2 of the transcript, E introduces the example of an old lady who was a Red Cross nurse. In l. 3, E wants to give the additional information that the nurse witnessed war scenes. However, she fails to produce the phrase de guerre ‘of war’ due to a tip-of-the-tongue-process. Note that the syntactic format of E’s utterance sur le lieux strongly suggests that she will continue with a prepositional phrase introduced by de, which specifies which places she is talking about (after all, le lieux is discourse-new and unidentifiable to D without specification). D’s in-situ-Ø-interrogative in l. 6 repeats E’s aborted utterance phrase, but adds the preposition de, thereby inviting E to repair her own previous utterance in l. 3. E tries to do so in l. 7, but is still unable to complete the utterance, which prompts a candidate answer by D in l. 8. In l. 9-10, E accepts D’s proposed answer and continues her narration in l. 11.

D’s in-situ-Ø-interrogative is characterized by a high degree of anaphoricity, since its interpretation relies on structural latency. Repair initiation in-situ-Ø-interrogatives are necessarily echoic and thus highly context-sensitive. Their use is not restricted to incomplete prior utterances, as repair initiation in-situ-Ø-interrogatives can also ask the respondent to repeat an element from a previous utterance that the requester has not understood (cf. Persson, Reference Persson2017: 239, for one such example from the C-ORAL ROM data). With a usage frequency of n = 5, repair initiation in-situ-Ø-interrogatives make up the bulk of my data. In Rosemeyer (Reference Rosemeyer2018b) and Garassino (Reference Garassino2022), it was shown that in-situ-wh-interrogatives can be used in the same discourse contexts.

In Persson’s category of open-ended information requests, at least two subtypes of information requests can be distinguished. This difference crucially correlates to the productivity of wh-interrogatives in French and Spanish. As was shown in the discussion of example (6), Elaboration information requests “are used to clarify or to add further details to a discourse topic raised in the previous context” (Garassino, Reference Garassino2022: 33). This situated meaning arises in contexts in which the proposition of the interrogative is either active or inferable from a previous utterance. In this criterion, Elaboration information requests differ from New Topic information requests, a situated meaning that arises in contexts in which the proposition of the interrogative is not active or inferable. While information-requesting uses of in-situ-wh-interrogatives in Spanish are mostly restricted to Elaboration contexts, French allows for New Topic in-situ-wh.

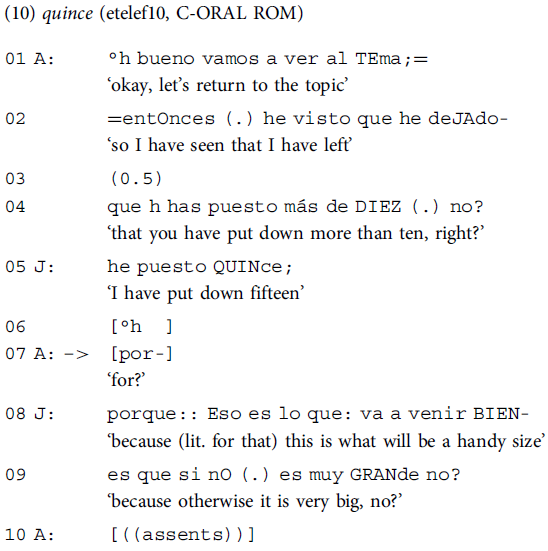

In my data, I document the use of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives both in Elaboration and New Topic functions for both languages. The transcript in (10) exemplifies the use of Elaboration in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in Spanish. The sequence occurs in a telephone conversation between colleagues who have just finished talking about a different topic. In l. 1, A starts to talk about a form that J has filled out. After an aborted utterance in l. 2 followed by a pause in l. 3, he asserts that he has seen that J has written a number higher than ten in one of the slots in the form. The formulation más de diez ‘more than ten’ suggests that A did not expect the number to be this high, giving way to the inference that the number was too high. However, in l. 5, J corrects A, claiming that he put down an even higher number, fifteen. Given that A has signaled that he believed that any number higher than ten is unexpected, and maybe even problematic, J’s assertion has a strong face-threatening potential. J seems to be aware of this fact. Directly after the assertion, he inhales loudly (l. 6). This intake of breath at a transition-relevant place seems to indicate that due to the controversial nature of this assertion, an explanation might be in order, which he might intend to deliver. This assumption is in line with previous studies on the functions of breathing in interaction, which have shown inbreaths to be “proxies for pragmatic completeness of the previous utterance” (Wlodarczak and Heldner, Reference Wlodarczak and Heldner2020). However, in l. 7, A leapfrogs J, requesting an explanation with the in-situ-Ø-interrogative por ‘for’, a preposition that forms part of the fused interrogative adverb porqué ‘why, lit. for what’. In l. 8-9, J delivers this explanation and achieves assent by A in l. 10.

As in (9), the in-situ-Ø interrogative por in example (10) is characterized by a high degree of anaphoricity. In particular, both the complete syntactical structure of por and the proposition of the interrogative have to be reconstructed through structural latency ([has puesto quince] por.? ‘you put down fifteen for…?’). However, there is one crucial difference between (9) and (10). In particular, in the description of example (9) it was argued that the continuation of E’s utterance with the preposition de is expected because the phrase le lieux would otherwise be unidentifiable to D. In contrast, in (10), J clearly did not intend to continue his utterance with por. From a discourse-pragmatic perspective, this means that A’s interrogative in (10) requests additional information about a state of affairs that is already manifest to both A and J, i.e., it has the discourse-pragmatic function of Elaboration.

Given that the use of in-situ-wh-interrogatives is frequent in contexts such as the one in (10), we have to ask ourselves what motivates A’s choice not to produce the wh-pronoun qué ‘what’ in (10). It seems reasonable to assume that A’s choice of the in-situ-Ø-interrogative is motivated by reasons of efficient language production. In line with my description, A is confident that J will be able to interpret his interrogative along the lines of ‘you put down fifteen because of what?’ because the structure of J’s previous turn has signaled that J himself expects a continuation of the topic and, more specifically, that he might have to deliver an explanation for his choice to put down fifteen. Consequently, example (10) demonstrates an interaction between context sensitivity and efficient language production: the strong expectedness of A’s information request licenses a minimal syntactic format. This interaction is well-known in typological studies; indeed, Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath, MacWhinney, Malchukov and Moravcsik2014: 196) argues that “the more predictable an aspect of a message is, the less coding effort one needs to get it across to the hearer.”

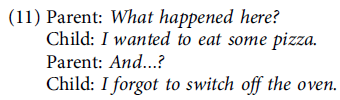

In (10), a further factor that undeniably contributes to the strong expectedness of the information request is the high transitional probability between por and qué in Spanish due to the existence of the complex interrogative pronoun por qué. However, this realization does not contradict the relevance of context sensitivity for the interpretation of such interrogatives. For instance, similar effects apply to Elaboration in-situ-Ø-interrogatives with and, as in the invented English example in (11).

As was mentioned in Section 2, another important correlate to context sensitivity is answerability. The strong expectedness of A’s information request in (10) generates the expectation that J will be able to provide an answer to the question. A presents his information request such that he is in no position to volunteer a possible answer himself, whereas this should not pose any problem for J. The high degree of answerability contributes to the efficiency of A’s information request: a in-situ-Ø-interrogative such as the one in (10) is not only efficient in the minimality of its form, but also in function, as such an interrogative is extremely likely to generate the desired reaction by the hearer. This also explains the strong face-threatening potential of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in contexts such as (11), where the use of and…? seems to implicate that the child should have produced this information even before the interrogative was uttered.

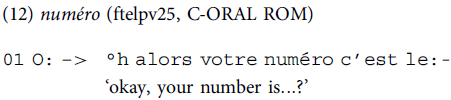

The final situated meaning expressed by in-situ-Ø-interrogatives is the New Topic function, in which an interrogative is used to request an information that establishes a (relatively) new topic in conversation. Like in-situ-wh-interrogatives (cf. Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2018b; Garassino, Reference Garassino2022), the use of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives is least frequent in these contexts both in French and Spanish. In my data, only one clear example of this function was found for French (12), and this example was already described in Persson (Reference Persson2017: 234-236), which is why I will not describe it in detail here.

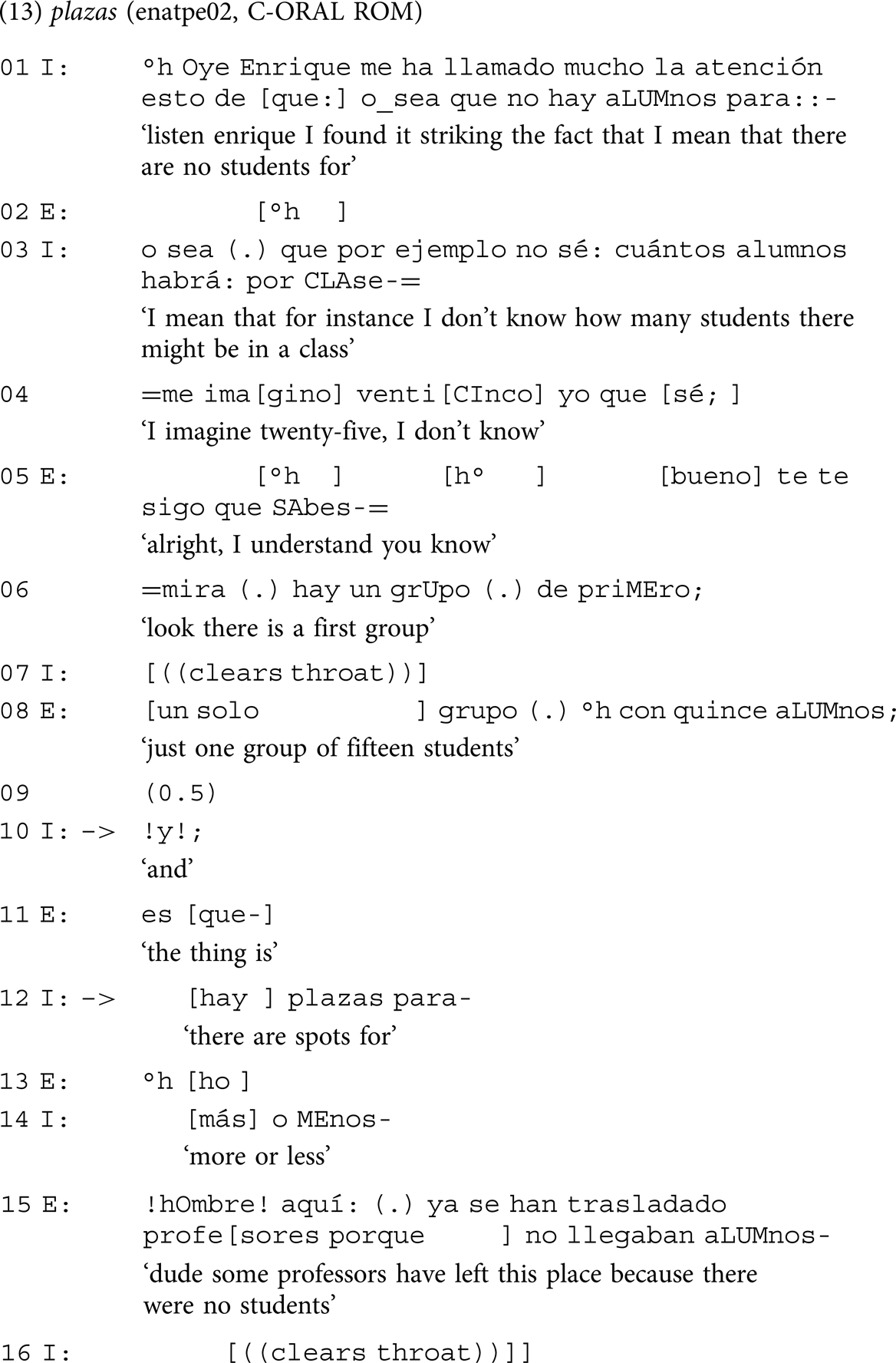

The transcript in (13) contains two in-situ-Ø-interrogatives from a Spanish conversation in a professional explanation context. E (Enrique), a teacher, has been describing to I to which degree immigrant children can adapt to his school. In l. 1-3, I changes the topic to a detail related to E’s previous account, namely the question of how many students are there in E’s class. After offering a candidate answer in l. 4, E tries to respond to her request (l. 5-9). Given the somewhat convoluted structure of I’s information request in l. 1-4, E first reassures her that he understands her request (l. 5) and then goes on to respond to it (l. 6). However, his response mira, hay un grupo de primero ‘look, there is a first group’ clearly does not answer I’s information request, which might be why I responds by clearing her throat (l. 7). In l. 8, E goes on to describe this first group, for which he does give the number of students, i.e., the information relevant to I. There is a relatively short but significant pause after E’s utterance (l. 9). The fact that I does not use this pause to take over the turn suggests that she waits for E to provide more information that might satisfy her request for information. When E fails to do so, she produces the in-situ-Ø-interrogative y ‘and’ (l. 10). This in-situ-Ø-interrogative very much resembles the English invented example in (11); I asks E to elaborate his response by providing more information that answers her initial information request. The small pitch step upwards (indicated in the transcript by exclamation marks) emphasizes the relevance of this request; I clearly does not know the answer to her information request and signals her strong interest in attaining a completion of the information through E. The interrogative has a strong face-threatening potential. It suggests that E should have already provided the information in his previous attempt to respond to I’s initial information request. However, E clearly seems incapable of providing such an answer, which is why, in l. 11, he uses the “inferential” es que ‘the thing is’ construction (Delahunty, Reference Delahunty1995) to introduce a reason for his non-preferred response. In l. 12, I interrupts this response and specifies her information request, now using the in-situ-Ø-interrogative hay plazas para ‘there are spots for’, which can be paraphrased as ‘how many slots are there?’. In l. 13, E starts to respond to this more specific information request, but is again interrupted by I in l. 14, where she tries to accommodate E by ramping down her expectation as to the precision to the answer. Again, this strategy signals the relevance I attributes to obtaining this information. In l. 15, E is finally able to produce a complete response, which is continued until after the end of the transcript. Using the pragmatic marker hombre ‘dude’, he again signals his inability to provide this answer, but goes on indicating that there really seem to be few students, since some teachers have actually left the school because of this problem.

Apart from the lack of the wh-element, the in-situ-Ø-interrogative in l. 12 (hay plazas para…?) is a syntactically complete structure, with a subject (plazas ‘spots’) and a verb (hay ‘there are’). As a result, it is characterized by a much lesser degree of context sensitivity than, for instance, the in-situ-Ø-interrogative por…? in example (10), whose interpretation relies on structural latency. Concomitantly, it expresses a discourse-pragmatic function that can be described as a New Topic information request. The interrogative establishes a discourse topic that is much less dependent on the previous context than the discourse topic established by Elaboration interrogatives.

To summarize, my corpus study has demonstrated that in-situ-Ø-interrogatives are used in French and Spanish with the same situated meanings as in-situ-wh-interrogatives, which suggests some structured variation between the two types of interrogatives. Likewise, the analysis seems to confirm that this opposition is governed by the degree of context sensitivity of these interrogative types. In particular, the use of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives is characterized by an even higher degree of anaphoricity and, concomitantly, a strong expectation that the hearer can and must respond to the information request, than the use of in-situ-wh. Consequently, my analysis makes the prediction that the difference between the two interrogative types is governed by efficiency considerations. Even more so than in-situ-wh-interrogatives, in-situ-Ø-interrogatives allow for an extremely reduced syntactic format while at the same time ensuring an even higher conditional relevance (Schegloff, Reference Schegloff1968: 1083) of the response, increasing the likelihood of such a response. This consideration explains why in my corpus, the use of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives is relatively frequent professional telephone conversations and teaching and explanation situations. In contrast to informal conversations between friends, these contexts are centered around the transmission and receipt of information, which is why the use of less explicit, more economic linguistics expressions is particularly relevant in such situations.

4. QUESTIONNAIRE STUDY

While my corpus study has offered good evidence for two of the hypotheses established at the end of Section 2, namely that in-situ-Ø-interrogatives are used in similar contexts as in-situ-wh-interrogatives but are characterized by an even higher degree of context sensitivity than in-situ-wh-interrogatives, due to the scarcity of data no evidence for the third hypothesis (differences in the preference of using in-situ-wh- over in-situ-Ø-interrogatives between French and Spanish) was found. In particular, it is unclear to which degree the use of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives differs across French and Spanish, and whether such a difference is related to the productivity of in-situ-wh in these languages.

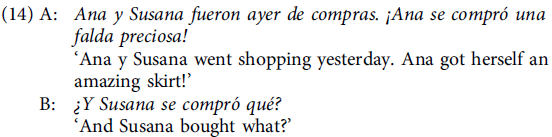

In order to confirm the results from the corpus study and assess the validity of the third hypothesis, I conducted a questionnaire study on the use of in-situ-Ø and in-situ-wh in French and Spanish. I restricted this study to a context in which the productivity of French and Spanish in-situ-wh differs, i.e., information requests. As was mentioned in Section 2, according to Biezma (Reference Biezma, Berns, Jacobs and Nouveau2018), the use of in-situ-wh-interrogatives in contexts such as (14) is only possible in the presence of a conjunction such as y ‘and’, which explicitly anchors the interrogative in the preceding context.

Crucially, the use of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives seems acceptable in such contexts, as well (15), and omission of the conjunction y seems to impact this acceptability negatively. If in-situ-wh and in-situ-Ø-interrogatives do indeed differ in terms of context sensitivity, we would expect omission of the conjunction to affect the acceptability of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives to a greater degree than in-situ-wh-interrogatives.

A second prediction relates to the issue of the productivity of these constructions in French and Spanish. If, as has been shown by studies such as Lefeuvre (Reference Lefeuvre2020) and Garassino (Reference Garassino2022), the use of in-situ-wh-interrogatives has become frequent in New Topic contexts at least in spoken French, they should be more acceptable to French speakers than to Spanish speakers in contexts such as (15). Such a conventionalization process would likewise entail that the original functional specialization of in-situ-wh-interrogatives gradually disappears as the construction starts to replace ex-situ wh-interrogatives in spoken French. In contrast, my corpus study has shown in-situ-Ø-interrogatives to be infrequent in both spoken French and Spanish, and likewise shown its situated meanings to be predictable from the anaphorical usage contexts that these interrogatives are typically used in. As a result, there is no reason for assuming a difference in the acceptability of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in the two languages. Taken together, this would lead to the prediction that French speakers prefer the more conventional and productive in-situ-wh over in-situ-Ø-interrogatives, whereas due to the low productivity of in-situ-wh in Spanish, no such difference can be found for Spanish.

Twenty native speakers of French and 20 native speakers of Spanish read 20 dialogues varying the structure in (14) on the online experiment platform onexp.co.Footnote 7 For the French participants, age varied between 18 and 40 years, for the Spanish participants, between 18 and 31 years. Participation in the experiment was paid according to the platform policies.

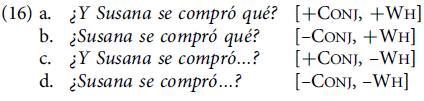

The materials were varied according to the two variables Conj (whether or not a conjunction is used) and Wh (in-situ-wh vs. in-situ-Ø), yielding four conditions. (16) illustrates these conditions for my initial Spanish example:

The materials were presented in a Latin Square design, such that each participant saw five examples of each of the conditions in (16), without repetition of a single stimulus. They were asked to evaluate on a Likert scale between 1 and 6 to which degree the target sentence (i.e., the interrogative) seems natural to them, where 1 was described as ‘not at all natural’ and 6 as ‘totally natural’. No distractor stimuli were used because of the obviousness of the task to the participants.

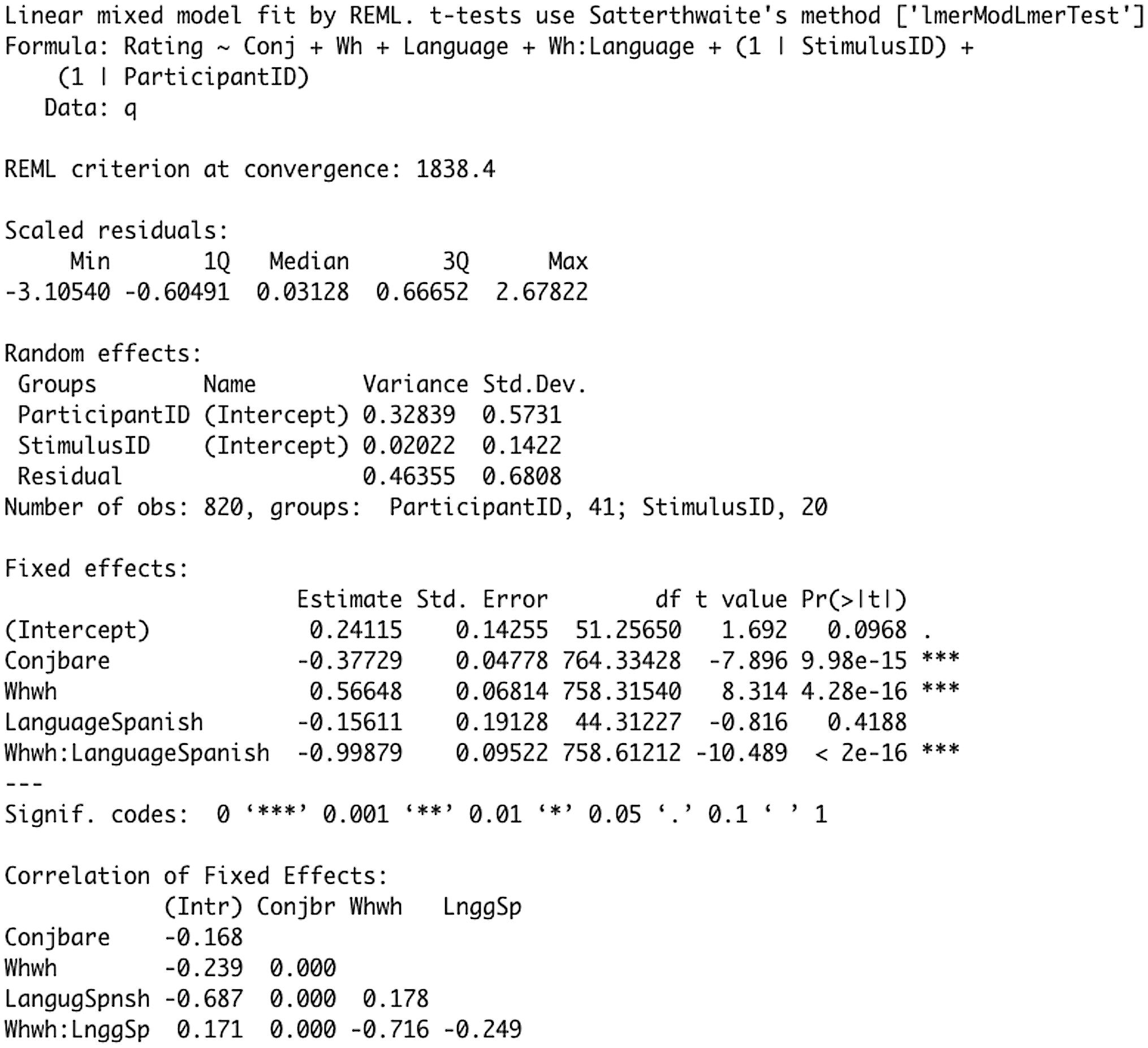

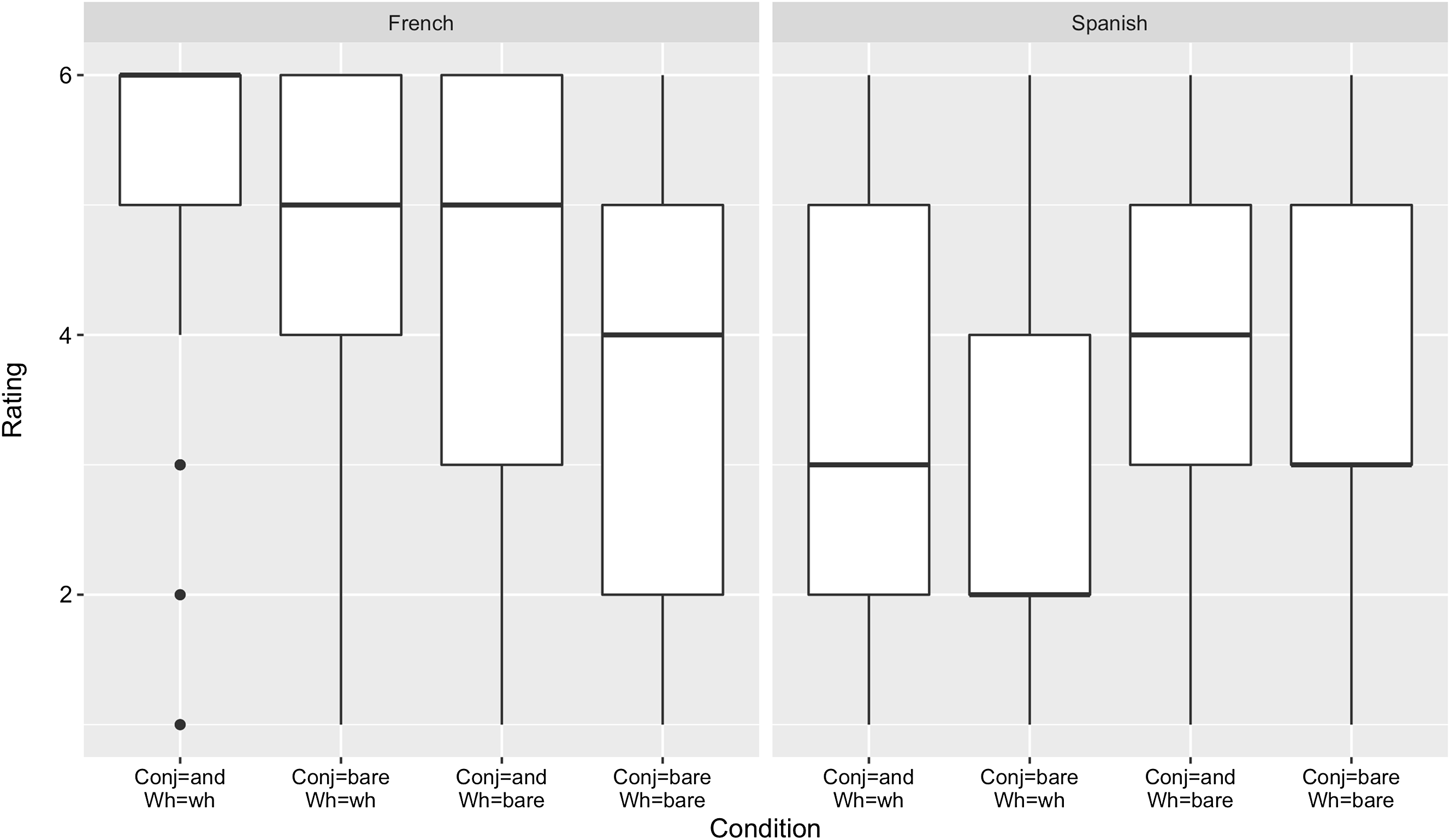

Figure 1 visualizes the mean ratings for the four conditions in the French and Spanish questionnaire studies.Footnote 8 With respect to the impact of conjunction usage on in-situ- and in-situ-Ø-interrogatives, results demonstrate a monotonic effect of conjunction usage. Irrespective of the language and the construction, interrogatives receive a higher rating when prefaced with the conjunctions et or y ‘and’. As regards the acceptability of in-situ-wh and in-situ-Ø, the results demonstrate a difference between French and Spanish participants. In general, French participants rated both in-situ-wh and in-situ-Ø higher than Spanish participants. However, in terms of the relative acceptability of in-situ-wh and in-situ-Ø, French participants preferred the use of in-situ-wh (mean rating 5.5) over in-situ-Ø (mean rating 4.5), whereas results for Spanish show the opposite picture: Spanish participants preferred in-situ-Ø (mean rating 3.5) over in-situ-wh (mean rating 2.5). These effects were tested for significance using a linear mixed-effects regression model, with the random effects StimulusID and ParticipantID (referring to the specific dialogue, i.e. stimulus, and the participant) in R (Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Haubo Bojesen Christensen2017; Pinheiro et al., Reference Pinheiro, Bates, DebRoy and Sarkar2018).Footnote 9 The regression model, reported in detail in the appendix, found all of the reported effects to be statistically significant, with the important exception of the difference in the acceptability of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in French and Spanish. Consequently, the model establishes that French and Spanish speakers did not differ at all in their acceptability of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives, whereas strong differences are documented for in-situ-wh-interrogatives.

Figure 1. Mean ratings for the four conditions in the French and Spanish questionnaire studies on in-situ and in-situ-Ø-interrogatives

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This article has established a description of the usage of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in French and Spanish, comparing its distribution with in-situ-wh-interrogatives. In a first step, the use of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in a corpus of spoken French and Spanish was described. In-situ-Ø-interrogatives and in-situ-wh-interrogatives can be used with the same situated meanings: as repair initiators, Elaboration information requests, and New Topic information requests. In-situ-Ø-interrogatives and in-situ-wh-interrogatives thus compete for the same usage contexts and can be described as variants. However, the analysis also showed important differences between these interrogative types. In particular, use of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives is even more strongly associated used to anaphoric contexts, where the precise nature of the requested information is evident to the hearer even though it is not specified using a wh-element. Crucially, in such contexts the information request itself is highly expected by the hearer, and the requester is particularly certain that the hearer will be able to respond in the preferred manner to the information request. Consequently, in-situ-Ø-interrogatives realize particularly efficient information requests both in terms of the speaker’s aims in discourse (high probability to receive the requested information) and production efficiency (minimal syntactic format). This explains another interesting finding, i.e., the fact that the usage of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives is typical for situations centered around the transmission and receipt of information. The corpus study showed a relatively high usage frequency of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in professional telephone conversations, teaching contexts, and professional explanations.

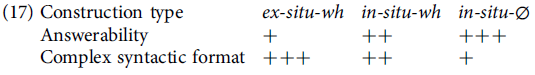

The proposed trade-off between context sensitivity and efficient language production has important ramifications for the description of the variation between ex-situ-wh-, in-situ-wh- and in-situ-Ø-interrogatives. In particular, the article suggests a continuum between these interrogative types in terms of answerability, i.e., expectation that the hearer will be able to provide an answer, and the degree of complexity of the syntactic format (Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2019a: 173-174). This continuum can be modeled schematically as in (17).

The model in (17) suggests that ex-situ-wh-interrogatives display the greatest degree of conventionalization and consequently, the most complex syntactic format (high degree of explicitness and preposed wh-constituent). As a result of their high degree of conventionalization, ex-situ-wh-interrogatives are least restricted in terms of discourse functions. In-situ-wh-interrogatives display a lower degree of conventionalization than ex-situ-wh-interrogatives, but a higher degree than in-situ-Ø-interrogatives.Footnote 10 They also occupy a mid-position in the continuum in terms of complexity of syntactic structure: while most arguments are typically explicit, in-situ-wh can be described as less complex than ex-situ-wh in that they formally resemble declaratives. Finally, in-situ-Ø-interrogatives display the lowest degree of conventionalization and the least complex syntactic structure. As a result, they occur with the most restricted set of discourse functions.

Note that the differences in terms of syntactic complexity between the studied wh-interrogative constructions are also reflected in the type of requested information. The analysis has suggested that use of in-situ-Ø is restricted to contexts in which the interrogative pronouns quoi/qué would be used. In contrast, both ex-situ- and in-situ-wh-interrogatives can be used with different interrogative pronouns/adverbs, such as quel/cuál ‘which’, combien /cuánto ‘how much’ or comment/cómo ‘how’ (Garassino Reference Garassino2022: 38). Given that selection of interrogative pronouns/adverbs represents semantic differences between the asked-for elements (e.g., who for persons, where for places etc., cf. Le Goffic, Reference Le Goffic2007: 21-23), this means that information requested by in-situ-Ø-interrogatives is necessarily of a particular type.

Larrivée (Reference Larrivée, Feldhausen, Elsig, Kuchenbrandt and Neuhaus2019: 127) suggests that “rare emerging grammatical variables [the use of in-situ-wh] representing less than 1% of uses in a grammatical category are characterised by a pragmatic value of explicit activation”. The continuum proposed in (17) offers an explanation of this effect: historical conventionalization of the use of interrogative constructions leads to an intrusion of these interrogatives into low-answerability contexts (cf. also Waltereit, Reference Waltereit2018; Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2019a). In such contexts, however, these interrogatives need to be clearly marked as interrogatives in order to be recognizable as such (recall the discussion of example 8 in Section 3).

Interestingly, the corpus study did not find any evidence for differences in the productivity of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in French and Spanish. I conducted a questionnaire study measuring the acceptability of French and Spanish in-situ and in-situ-Ø-interrogatives. In line with previous studies, results indicated that in both languages, in-situ and in-situ-Ø-interrogatives are more acceptable in such contexts when introduced with et/y. Likewise, the study demonstrated a higher acceptability of in-situ-wh-interrogatives for French than for Spanish. Crucially, however, no evidence was found for the assumption of a difference in acceptability of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives in French and Spanish. French speakers thus prefer in-situ-wh over in-situ-Ø in the studied contexts, whereas Spanish speakers actually prefer in-situ-Ø, mirroring the lack of conventionalization of in-situ-wh in Spanish.

These results are in line with a description of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives as a non-conventionalized ad-hoc strategy for realizing information requests. Indeed, one might argue that the possibility of a conventionalization of in-situ-Ø-interrogatives as a more common type of information request is blocked by the fact that in-situ-Ø-interrogatives lack a wh-element. Due to the underspecified semantics of this interrogative type, in-situ-Ø-interrogatives are necessarily anaphoric and resist generalization to New Topic information requests, unlike in-situ-wh-interrogatives.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Oliver Ehmer, as well as the audiences at the workshop “L’interrogative in situ : aspects formels, pragmatiques et variationnels” (13 June 2022) and the Romance Linguistics Colloquium at the Freie Universität Berlin (5 January 2022), the three anonymous reviewers, and the editors of the special issue for comments on previous versions of this paper. All remaining mistakes are my own.

Competing interests declaration

The author declares none.

Appendix

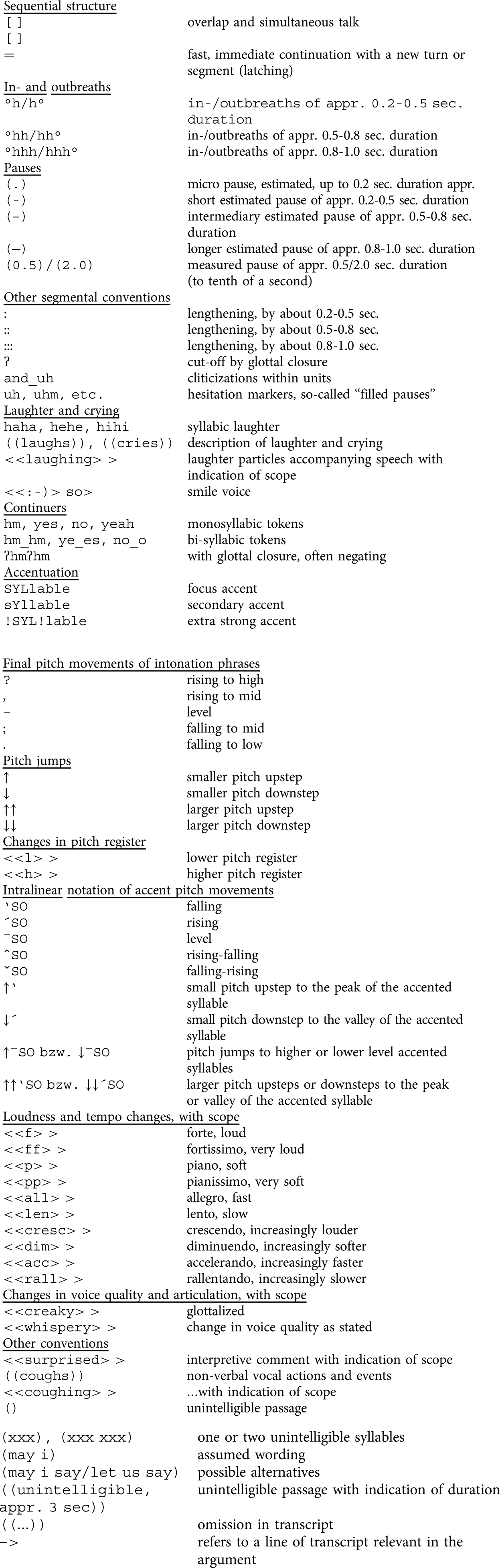

Summary of the most important GAT 2 transcription conventions

cf. Selting et al. (Reference Selting, Auer, Barth-Weingarten and Bergmann2009)

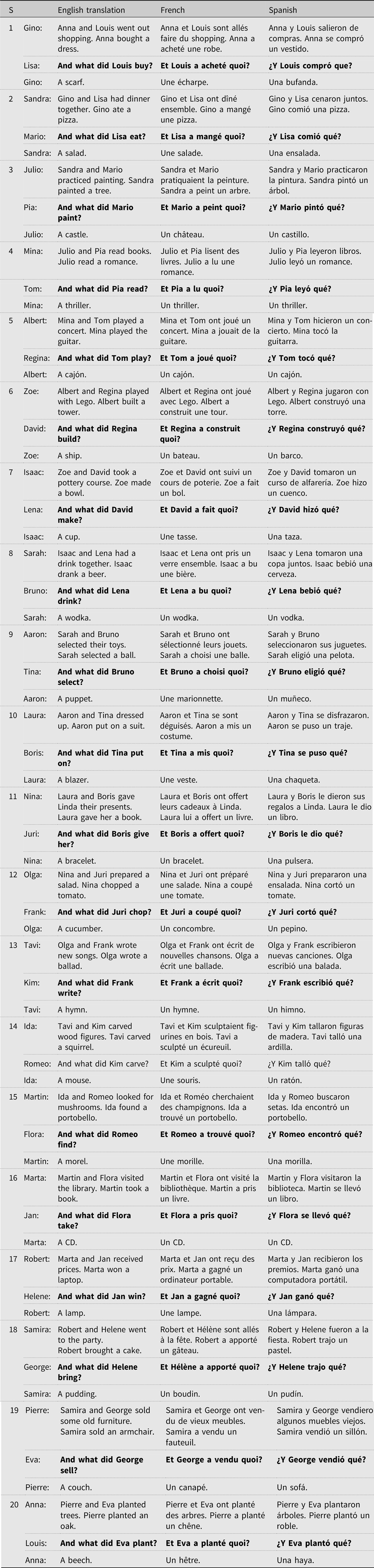

Materials employed in the questionnaire study

Note that the target sentence (marked in bold font) was modified according to the two conditions Conj (use of conjunction) and Wh (use of wh-element). Here, only the condition [+Conj, +Wh] is given. The English translation is given for clarity of presentation and was not part of the experiment. Abbreviations: S = Stimulus.

Results from the mixed-effects linear regression model measuring the correlation between acceptability rates and the variables Conj, Wh, and Language, in the questionnaire study

Model evaluation statistics: AIC = 1854.4, marginal R2 = 0.2, conditional R² = 0.5.