Throughout their careers, from medical school on, physicians periodically experience awe when contemplating the development and evolution of human beings, the physiology of health and the pathogenesis and effects of disease. Disordered processes of the vegetative functions of eating, sleeping and sexual expression, which are evident in every branch of clinical medicine, are rarely defined as among medicine's important challenges. A small group of health professionals have carved out the niche of clinical sexuality as a focus of their careers. Among their responsibilities has been the education of other health professionals about what is known about sexuality and how its numerous problems may be treated. Medicine's clinical interest in sexuality and its problems is far from new. The classification and theories of the causes of sexual problems and their means of treatment date to the earliest of medical writing (Reference BerryBerry 2013). These topics continue to evolve. Today, the sexual patterns that attract the most clinical attention involve three broad categories:

-

• sexual identity – transpositions of gender identity, variations in orientation, and paraphilic patterns of arousal within and outside of a sexual addiction pattern

-

• sexual dysfunction – lack of sexual desire, incapacities to maintain sexual arousal, inabilities to attain orgasm, orgasm without pleasure, premature ejaculation, painful intercourse, unwanted sexual arousal and intense lasting post-orgasmic exhaustion

-

• relational unhappiness – failures in finding a partner to love and maintaining harmony in established relationships.

Modern psychiatrists, psychologists, relationship therapists, sex therapists and counsellors, urologists, gynaecologists, infectious disease specialists and physical therapists who have an interest in sexual medicine each stake out their territories within this broad array. Individual professional turfs are relatively narrow. Each field has its own take on aetiology and different preferred therapeutic tools. However, all specialists have a tendency to overlook a vital basic principle, that:

‘All sexual behaviour – solitary or partnered, normal or dysfunctional, morally acceptable or socially disapproved of – is constructed from four general sources: biology, psychology, interpersonal relationships and culture’ (Reference LevineLevine 2007).

Sexual healthcare professionals are forced by education, knowledge and skills to oversimplify this ordinary complexity (Reference PerelmanPerelman 2009), but the sexual lives of patients are rarely as simple as we professionals initially conceive them to be. Although this principle provides an antidote for professional arrogance, it does not help us understand why sex is important, which is the ultimate goal of this article. The answer to this question is far more intuitive and observational than based in data-bound science.

Whether or not it was justified, surveys from the 1970s suggested that patients assumed that physicians were trustworthy knowledgeable advisors about human sexuality (Reference MauriceMaurice 1999). Even today, patients expect professionals to understand human sexuality and their inchoate experience of it in their lives. Patients expect us to have a grasp of sexuality's potential for profound psychological and physical pleasures, to understand its frequent disappointments and to be able to identify its recurring impediments in their lives. This article is designed to help professionals live up to their expectations by posing answers to rarely asked questions.

How are adults nurtured in sexual relationships?

Adult sexual relationships are well known to have the potential to stabilise and enrich individuals and to make them happy with their interpersonal status. Psychological intimacy and partnered sexual behaviour are the two behavioural systems that nurture adults. Partnered sexual behaviour can exist without psychological intimacy just as psychological intimacy can occur without partnered sexual behaviour. When they are successfully integrated, however, a positive feedback between them creates a greater degree of mutual nurturance and results in maximisation of sexual functional capacities. Psychological intimacy motivates partnered sexual behaviour and sexual behaviours create a new degree of psychological intimacy. In sexual health, the two interlocking systems function as one. This pattern can be seen in long-term relationships regardless of marital status and sexual orientation.

Case vignette: nurturing an empty marriageFootnote a

Phil and Madeleine estimated that they had not had sex for the previous 10 years of their 35-year marriage. Her 4 years of sobriety and psychotherapy have enabled her to make remarkable progress with how she deals with people. No longer passive-aggressive, she is now direct; no longer depressed and isolating, she has rediscovered her ability to have good friends and to be engaging. She has reached the point of either wanting more from her highly functioning but aloof husband or wanting a separation. Phil, she reported, rejected her invitation to cuddle during their last vacation. ‘We are over that phase’, the executive said, not wanting to pretend affection he does not feel and fearing it might lead to sex, which he doubted he could perform because of their long polite estrangement. Now months later, the couple is asking for help in making a decision whether to divorce. ‘I love and respect you for your great accomplishments and want to always be friends with you but we are only room mates now,’ Phil pronounced. ‘I need your attention, interest and affection – not sex. You just avoid me, living your work and recreation. We share almost nothing anymore’. He continued, ‘I'll do what you want about the marriage, but it is a shame to ruin what we have materially built together’. Calmly, sadly, Madeleine responded, ‘Do you see? You tell me nothing about your feelings – just concepts. I need to know about you as a person!’

When I told them of the two systems of nurturance in marriage, they immediately understood that this aptly described the emptiness of their lives. They agreed that they had never thought of the term nurturance, but hearing it reassured them that I understood what they were talking about and how much had to change to recreate a different quality of life for each of them.

How is psychological intimacy created?

There are three ways of promoting psychological intimacy: by conversation, by shared intense experiences and by sexual behaviour. Each of these avenues promotes the sense of loving and being loved.

Conversation

The usual way to attain psychological intimacy is through talking (Reference LevineLevine 1991). One person speaks; the other person listens. To achieve a moment of psychological intimacy, the speaker has to meet three requirements. The speaker must talk about his or her inner subjective psychological self. The speaker must be able to trust in the safety of sharing this with the listener. The speaker must possess the language skills to express his or her thoughts, feelings, perceptions and history in words (Box 1).

BOX 1 Psychological intimacy: speaker requirements

-

• Speakers must reveal aspects of their inner psychological selves

-

• Speakers must trust their psychological safety in sharing their subjective selves

-

• Speakers must have the verbal skills to express their thoughts, feelings, perceptions and history in words

Psychological intimacy will not occur, however, unless the listener is able to evidence the following characteristics: to give undivided, uninterrupted attention to the speaker; to make non-critical comments that reflect an accurate comprehension of what is being said and felt by the speaker; and to construe the opportunity to listen as a privilege enabling learning about the inner experiences of the speaker (Box 2). By this standard, most conversations, even between established lovers, do not create psychological intimacy.

BOX 2 Psychological intimacy: listener requirements

-

• Listeners must provide undivided attention with a minimum of interruptions

-

• Listeners must not criticise, correct or disagree with what is said

-

• Listeners must accurately comprehend what the speaker is feeling and saying

-

• Listeners must recognise and sense the privilege of hearing what is being said

Psychological intimacy is a transformative moment of connection that occurs simultaneously in both the speaker and the listener. It is a bonding process that creates or reinforces the sense of belonging to one another.

Psychological intimacy exists in two forms. The first is the two-way psychological intimacy that ideally recurs in a couple's life. Each member of the couple, of course, takes a turn being a speaker and a listener to potentially recreate moments of connection. In one-way psychological intimacy, however, a particular person is almost always the speaker and the other person is predominantly the listener. Mental health professionals create a one-way psychological intimacy with patients, as do parents with their young children. Psychological intimacies are part of the landscape of numerous kinds of relationships, ranging from friendship to sibling bonds to lawyer–client relationships. Unlike this wide array of psychological intimacies, psychological intimacy within a sexual relationship possesses a special power to repeatedly ease the way to sexual behaviour.

These bonding moments of connection have profound consequences for the speaker. The moments strengthen the attachment to the listener, causing pleasing thoughts such as ‘I am accepted’, ‘I feel more stable’, ‘I am happier’ and ‘I feel healthier’. They erase loneliness, create optimism and cause the speaker to look forward to the next opportunity for connection. After repeated moments of psychological intimacy, the speaker generates interest in sexual behaviour with the listener. Psychological intimacy is a powerful erotic stimulus. In certain contexts it is the most reliable and safest known aphrodisiac.

These moments have positive consequences for the listener as well. The listener gains a deeper understanding of the speaker and experiences pleasure in being of value to the speaker. The listener demonstrates an increased willingness to think about their own subjective self and comes to realise how important they are to the speaker. These subjective experiences reaffirm the bond to the speaker.

Shared intense experiences

A second way of creating psychological intimacy does not require much conversation. An intense bond can readily be established or re-established through shared intense emotional experiences. For example, by enduring with a partner a frightening febrile illness in an infant, caring for a dying friend together, being together in combat or being on the same athletic team all produce psychological intimacy by virtue of shared intense emotional experience.

Sexual behaviour

The third way of attaining and maintaining psychological intimacy is through sexual behaviours. These, too, are largely non-verbal shared emotional experiences. Sex creates emotion in multiple ways. The sight of the partner's naked body is a powerful experience of knowing the person, particularly early in the relationship. To this is added the perception of what the naked person feels about their naked body. One learns of the partner's interest in and attitude towards specific sexual behaviours. Each person witnesses the other in arousal, a pleasurable knowledge that is augmented by facilitating, listening to and watching the partner's orgasm. These intensely private subjective experiences create the sense of knowing the partner in a way that others could not. This is a privilege. In these ways, sex creates a profound degree of connection.

A note on intimacy

The unmodified word ‘intimacy’ is used to describe shared conversations about private experiences, non-verbal emotional experiences and sexual pleasure. Patients often complain that intimacy is lacking in their relationship, but do not define the avenue or avenues that are lacking. Professionals can quickly clarify this. We can share what we know of speaker and listener requirements for achieving psychological intimacy (Boxes 1 and 2). If the patients can then achieve a new nurturing degree of psychological intimacy at home or in session with the professional, a sexual reawakening may occur.

What is learnt over time through sex?

Over time, individuals discover their partner's range of sexual comfort. They witness the changing nature of this comfort. They come to discern their own and their partner's variations in desire, arousal and orgasm. They appreciate some of their partner's motivations for sexual behaviours. Over months, years or decades, sexual behaviour may deepen the couple's bond such that each has a rich, nuanced conviction of the sensual capacities of the other and how best to relate to them (Reference Kleinplatz, Levine, Risen and AlthofKleinplatz 2010).

What accounts for the pleasures of sex?

The pleasures are physical and psychological. Sex can create novel delicious sensations and pleasant emotions before, during and after orgasm. A person experiences the sense of power in giving their partner pleasure. The ability to give and to receive pleasure increases interest in the other, adds to the knowledge of the other and creates the sense of being intertwined with the other. These are the means of creating a sense of oneness. The seamless interplay of physical and psychological pleasure during sex attenuates the sense of time as the individuals transport one another into the realm of sensation.

The psychological pleasures of sex involve personal meanings. These meanings, however, are often difficult to articulate or are privacies closely held from the partner. ‘I feel it, but I can't describe it. It just is!’ and ‘I love you!’ are occasional summaries of this complexity.

Why is sex important?

Sexual behaviour stabilises our sexual identity. Sex allows us to feel that we are confident as a man or woman. It helps us to refine and stabilise our identity as a heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual person. It clarifies the nature of our intentions as consisting of peaceable mutuality or varieties of sadomasochism or fetishism.

Sex is the vehicle for early romantic attachment at every stage in life – among the never attached, divorced, widowed and those having affairs. It can facilitate the vital process of creating an entity from two individuals. Romance conveys the hidden quest for a safe, secure, comforting, lasting unity. It is typically accompanied by an intense desire to bring their unclothed bodies together.

In established relationships, sexual behaviour reinforces the sense that one is loved and capable of loving. It strengthens the sense of oneness, enabling individuals to perceive themselves as an integral part of another. Sex has the capacities to erase the ordinary angers of everyday life, to elevate one's mood and to increase resilience for tomorrow. It improves our capacity to withstand extra-relationship temptation. And, of course, it is vital to our reproductive ambitions.

Sex remains a vehicle for self-discovery throughout life. It begins in adolescence, when eroticism is dominated by fantasy, attraction and masturbation, and continues to reveal private aspects of the self during the many decades of partnered sexual behaviours and into the wistful final alone years (Box 3).

BOX 3 The subtle functions of recurring partnered sexual behaviour

Recurring sexual behaviour with a partner:

-

• reveals and reinforces each person's sexual identity

-

• reassures that one is part of an established entity: one is loved and is loving

-

• erases the small angers and disappointments of everyday life

-

• improves the capacity to withstand extra-relationship temptation

-

• serves as a vehicle for discovery of one's feelings about the self and partner

-

• is (usually) essential for reproductive ambitions

Why is sexual experience unstable?

Men tend to be a bit more constant in their sexual function than are women, but this point should not be overemphasised because sexual experience is a dynamic ever-evolving process for all. This concept can be thought of as another principle. Sexual experience changes in the short and in the long term in response to numerous biological, psychological, interpersonal, economic and social factors. Individuals change psychologically, physically and sexually over time as they mature, take on new responsibilities as well as experience loss, personal dilemmas, and psychiatric and medical illnesses.

What is a couple's sexual equilibrium?

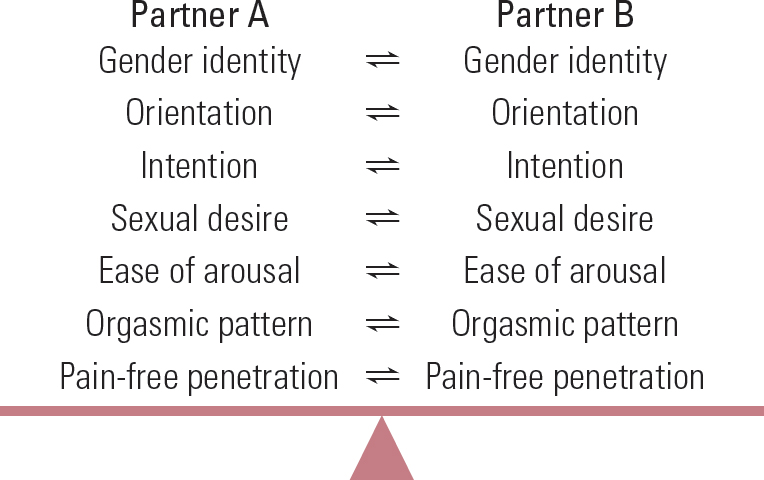

The exquisite dynamics of sexuality explain why the sexual fate of an individual entering into an exclusive relationship is not determined by their pre-commitment sexual capacities. What they experience in the new relationship will heavily depend on the interplay between their own and their partner's component characteristics (Fig. 1). The interaction of these components determines the frequency of sexual behaviour, what sexual acts they share, how orgasm is attained and their sexual psychological satisfaction. This ordinarily complex interaction is called the sexual equilibrium. Each couple has a unique one. Studying a couple's sexual equilibrium brings the physician to a systems perspective, which is a level of complexity beyond the usual individual perspective that psychiatrists have been educated to take with their patients.

FIG 1 The components that interact to create each subtly changeable sexual equilibrium.

Some individuals come to know over their life-time that different levels of satisfaction occur with different partners. Some chose to live their lives within two separate sexual equilibria: one with a spouse and another with a paramour. These men and women typically have a more satisfying, sensuous, functional sexual equilibrium with the paramour. In some instances, the spouse is aware of the other sexual partner.

Case vignette: seeking sexual equilibrium

Mort's work in land development was successful, but his marriage was not. Plagued by mysterious erection problems with his wife, he discovered anxiety-free consistent potency with his secretary over a 15-year period. Years after his divorce, he eventually found a ‘culturally and educationally suitable’ woman to marry. He and his secretary agreed to end their sexual relationship, but his fiancé could not tolerate her presence at his work. Despite much effort to negotiate this circumstance, the new ‘otherwise perfect’ relationship faltered. Mort lived the rest of his life as an apparently celibate man, maintaining his work and sexual life with his secretary.

What is sensuality?

Satisfying functional sex requires the abandonment of ordinary daily preoccupations and the substitution of a focus on bodily sensations. Sensuality is not how a person looks; rather, it is what a person is capable of doing and feeling during sex. Sensuality has two faces. The readily appreciated face is the capacity to experience the preoccupying sensations of a kiss, a lick, a touch, a breast or genital caress, and penetration. The more subtle face of sensuality is the person's interest in transporting the partner to this realm where pleasure predominates.

Is a life of sexual pleasure possible?

High on the list of personal expectations of life is to have, at least for an extended period of time, a diet of emotionally satisfying sex (Reference ByersByers 2005). It is as though individuals collectively know that sex can be wonderful and that it is a vehicle for feeling and expressing love. In the final analysis, sex may be the easy way to access the much more difficult-to-describe subject of love (Reference LevineLevine 2014). Particularly in medicine and psychiatry, where the topic of love is avoided, sex may be a surrogate topic for love – that is, we discuss sexual dysfunctions rather than impaired processes of loving that may have created the sexual problems.

A satisfying sexual life diminishes the sense that one has been cheated by fate. Wonderful sex creates a comforting, stabilising sense of happiness. People learn from it that in being a part of someone else, they do not lose their individuality by loving. They come to realise that their individuality is essential to their blissful sensual excursions. Satisfying sensual sex prevents envy of other people's sexual experiences because people sense that ‘It could not get better than this’.

While sexual pleasure can last a lifetime in some couples, the psychological and the physical components of that pleasure intersect in differing proportions over time. Many couples over 70 have retired from partnered sex, but are pleased to know that they had their share of wonderful sex when they were younger, healthier and had more sexual drive.

What is sexual health?

Recurrent, satisfying sensuous interactions are a developmental achievement. They represent the mastery of numerous forces that block the way to sexual health for others. Sexual health is not guaranteed for men or women by their biological normality, their sex-positive attitudes or history of sensuality, although these definitely help. Sexual health is a potential that is realised by individuals who intuitively understand that sex is important, want to be part of the process and sense its relationship-building and rebonding capacities. The maintenance of sexual health is a personal developmental accomplishment requiring good judgement about the handling of both sexual and non-sexual interactions. To make explicit what the sexually healthy person understands intuitively, we can say that sex has the potential:

-

• to please

-

• to stabilise

-

• to physically satisfy

-

• to emotionally satisfy

-

• to improve self-understanding

-

• to improve understanding of the partner

-

• to heighten the experience of being loved and of loving

-

• to enhance life through reproduction.

What are the sources of distress about sex?

Patients with sexual difficulties are currently lacking in the attainment of at least some of these potentials. Some have never, even briefly, attained them. Many have attained and lost them. Sexual distress is a requirement for the diagnosis of any sexual dysfunction in DSM-5. While rating scales can be used to quantify distress, the resultant numbers explain the intensity but not the sources of the distress (Reference Derogatis, Clayton and GoldsteinDerogatis 2011). Clinicians need to look no further than the eight items above to understand the sources. When sex does not please, stabilise, physically or emotionally satisfy, when it fails to improve understanding of the self and the partner, when it does not enhance the experience of love or create desired reproduction, sex is distressing. It is often distressing even when the patient does not initially appear distressed. Further discussion over time usually illuminates the disappointment in the patient's life about what might have been or what was lost and their ways of coping with it.

How do these concepts facilitate therapy?

Mental health professionals have important advantages over non-psychiatric physicians and other sexual medicine specialists. We tend to function closer to the principles of aetiological complexity and dynamic interplay than doctors who intervene biologically and pay only lip service to the psychological, interpersonal and cultural contexts of a patient's life, or who expect improvements to be well received and lasting. These solely biological interventions have a tendency to disappoint the patient and the doctor. Many a physician wonders why a large number of their prescriptions for oral treatments for erectile dysfunction are not refilled. We mental health professionals tend to be aware that there is more to erectile dysfunction than an uncooperative or unreliable penis. We know that changes in one person invariably have an impact on the partner. Therapeutic interventions can be immediately effective because of the rebalancing of the delicate interactions between two individuals’ sexual identity components and sexual function characteristics. They can fail because of unappreciated sensibilities emanating from the partner (Reference PerelmanPerelman 2009).

Even though our contact with the patient begins with our eliciting a history of the presenting sexual problem, the initial evaluation is actually a mutual process. The clinician is evaluating the sexual complaint by searching for the correct diagnosis and beginning to ascertain the pathogenesis and factors that dictate an approach to therapy. The individual patient or the couple is assessing the clinician's warmth, interest, empathy and understanding of their distress. Some pleasant initial evaluations are not followed by the patient's return for treatment. Some treatments are not continued for a reasonable duration. When this happens, clinicians need to consider the possibility that they did not meet the patient's evaluation criteria. From the patient's perspective, the goal of the sexual history-taking is the establishment of a hope-generating, trusting alliance with the clinician. There will be no therapy, despite an accurate diagnosis and a state-of-the-art treatment plan, if the clinician fails their unspoken audition. All clinicians occasionally fail to engender their patient's confidence.

To increase the odds of establishing patient trust, I recommend rejecting the idea of a complete sexual history. The specifics of the sexual history vary with the presenting problem, the specialty of the clinician, presumptions about the likely sources of the problem and the patient's capacity to talk about the matter. Despite the inherent pressure younger clinicians feel to gather a lot of information at the first encounter, there is another task to achieve first. This task, the creation of a therapeutic alliance, is a hopeful agreement to work together to attain an agreed goal. The sexual history and the doctor's ability to formulate the pathogenesis of the problem are evolving processes. Eventually, the history should reveal the individual's sexual identity components and sexual functional capacities (Fig. 1). It should clarify the partner's capacities and how they interact. It is asking too much of any clinician to obtain a picture of all of this by the end of the first meeting.

Understanding the patient's distress and disappointment with their sexual problem generates moments of empathy and one-sided psychological intimacy. This is how many clinicians pass their auditions with very high marks.

There are many ways of suffering over one's sexual identity and functional capacities, but there are also many subtle ways of ameliorating these concerns (Reference LevineLevine 2013: p. 133). While therapeutic processes are ultimately the clinician's responsibility, they do not happen without the doctor–patient or doctor–couple team each playing a vital mutually respectful role. In this article, I have suggested the hypothesis, which feels to me to be a clinical conviction, that understanding of why sex is important is the best first step to take in educating professionals about sexuality.

And what of Madeleine and Phil?

Doctor to Madeleine and Phil: ‘So how did I do on my audition?’

Madeleine (with laughter, warm smile): ‘You were great. Thank you.’

Phil (with laughter, first moment that he looked relaxed): ‘When can we come back?’

Two days later a phone message: ‘Please cancel our next appointment. Phil decided to go in a different direction.’

We professionals spend years improving our capacities to understand and to assist. Our skills can only be applied, however, when an individual patient or a couple have the ambition to improve their sexual equilibrium. Phil apparently realised that he did not desire to become sexual again with Madeleine. We illuminate, educate, support and encourage, but these vital processes are not sufficient unless the team is established. Often when it is not, this is due to definable patient factors. Discerning the differences between our deficiencies and patient factors protects our self-esteem and encourages our continuing professional growth.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Sexual equilibrium refers to:

-

a the balance of psychological conflicts within a person's mind that shapes their capacities to be aroused to orgasm

-

b the relationship between a person's value system acquired through immersion in their unique culture and their sexual capacities

-

c the determinative interaction between the component sexual identity and sexual function characteristics of each partner

-

d the insensitive fixed point of sexual function established by each couple

-

e the principle that sex is determined by four separate interacting forces, ranging from biology to culture.

-

-

2 Which of the following lists are matters of sexual identity only:

-

a gender questioning, gender queer, anorgasmic

-

b bisexuality, paedophilia, sexual interest-arousal disorder

-

c transvestism, erectile dysfunction, dyspareunia

-

d transsexualism, lesbianism, exhibitionism

-

e hypoactive sexual desire disorder, erectile dysfunction, painful ejaculation.

-

-

3 Psychological intimacy:

-

a can be taught through reading, practising in front of a therapist and by example within psychotherapy

-

b can be a powerful aphrodisiac for new relationships and can counteract sexual boredom in established relationships

-

c if consistent between a couple, facilitates continuing sexual behavior

-

d is profoundly deficient in many individuals seeking help for arousal and desire problems

-

e all of the above.

-

-

4 A life without sexual problems over 60 years of marriage:

-

a is readily accomplished by the vast majority of people

-

b requires an evolving attitude towards sex as one matures

-

c is likely to undergo considerable change in male capacity over this time

-

d is likely to undergo little change in female capacity until 20 years into menopause

-

e all of the above.

-

-

5 Taking a sexual history after an individual or couple brings up their sexual concern:

-

a should be thorough, beginning with childhood, moving through courtship up to the present day

-

b should focus primarily on the individual's (couple's) view of the cause

-

c should primarily demonstrate the doctor's comfort and knowledge of the topic

-

d should end with a definite treatment plan

-

e should display the doctor's awareness of the distress inherent in the complaint and attention to the individual's (couple's) comfort in working with the doctor further.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | c | 2 | d | 3 | e | 4 | b | 5 | e |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.