Introduction

On 1 November 2006, the Mental Health Act (MHA) 2001 replaced the previous legislation, the Mental Treatment Act (MTA) 1945, relating to the involuntary detention and treatment of patients in the Republic of Ireland. The MHA 2001 took into account international legal frameworks such as the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (1950), and the United Nations Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care (1991). Accordingly, the MHA 2001 updated the legislative framework within which a person with a mental disorder can be admitted, detained and treated involuntarily in an approved centre, with formal review of their detention and treatment at regular intervals. Individuals could be admitted involuntarily either as ‘temporary patients’ or ‘persons of unsound mind’ under the MTA 1945. The detention order for temporary patients lasted for 6 months and could be extended by periods of 6 months up to a maximum total duration of 18 months. The detention order for ‘persons of unsound mind’ was of indefinite duration. No formal review of detention orders was automatically undertaken under the MTA 1945. The process of transferring a patient into hospital under the MTA 1945 was largely similar to the present process under the MHA 2001. Under the MTA 1945, if the ‘resident medical superintendent’ (clinical director) was unable to provide staff to transfer an individual into hospital, the ‘authorised medical officer’ (i.e. general practitioner) could request the Gardai to transfer an individual to the appropriate ‘district mental hospital’. Although legal reforms of the MHA 2001 have enhanced the oversight of the involuntary admission process, there has been minimal impact on admission rates [Murray et al. Reference Murray, Hallahan and McDonald2009; Mental Health Commission (MHC) 2008; Ramsey et al. Reference Ramsey, Roche and O’Donoghue2013]. The number of individuals detained under the MHA 2001 since its introduction is virtually unchanged. For example, the rates of admissions of individuals/100 000 under the MHA 2001 (inclusive of the independent sector) was 47.12 in 2014, compared with 51.2 under the MTA 1945 (MHC Annual Reports, 2007, 2009, 2014; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Hallahan and McDonald2009). Furthermore, there has been minimal change in relation to the clinical profile or duration of detention of patients admitted involuntarily under the MHA 2001 compared with the MTA 1945 (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Hallahan and McDonald2009). A modest change in the identity of applicants has been demonstrated (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Hallahan and McDonald2009; MHC, 2010) with members of An Garda Siochana (Gardai) (Police) more frequently acting as applicants. Similar to the MTA 1945, however, family members remain the most common applicant group (MHC, 2014), despite the legislative capacity for authorised officers to act in this role.

To date, a number of studies have explored stakeholders’ views in relation to operational aspects of the MHA 2001. For example, consultant psychiatrists have expressed concern regarding increased workloads, the adversarial nature of mental health tribunals (particularly in interaction with solicitors), negative impacts of the MHA 2001 on therapeutic relationships with patients (Jabbar et al. Reference Jabbar, Doherty, Aziz and Kelly2010; Ramsey et al. Reference Ramsey, Roche and O’Donoghue2013), and negative effects on non-consultant hospital doctor (NCHD) training and care of voluntary patients (O’Donoghue & Moran, Reference O’Donoghue, Lyne, Hill, O’Rourke, Daly, Larkin, Feeney and O’Callaghan2009). General practitioners (GPs) have described particular difficulty transferring patients to approved centres due to significant time delays related to transport. This has resulted in difficulties managing patients with increased risk to the patient, family and GP reported (Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, O’Sulliva, Finnegan, Moran and Bradley2011). GPs have also described increased workloads (increased paperwork and a long duration of time is required for patient assessment and organisation of transfer to approved centre) and limited training opportunities for GPs available on the MHA 2001 (Jabbar et al. Reference Jabbar, Kelly and Casey2011). Psychiatric nurses [predominantly nurses working in acute psychiatric units, but also a small cohort of community mental health nurses (CMHNs) (n=9)], have expressed concern regarding increased workloads (particularly increased paperwork), change in the amount of time available to be with patients, and excessive focus on legalities within clinical practice (Doherty et al. Reference Doherty, Jabbar and Kelly2014). Although there have been no studies to date examining family members’ or carer’s views in relation to the MHA 2001, an adverse impact on their relationship with patients due to detention under the MHA 2001 has been reported (O’Donoghue et al. Reference O’Donoghue and Moran2009). Family members in the United Kingdom have previously expressed concern in relation to attaining support promptly from the mental health services when their relative is acutely unwell and requires involuntary admission (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Ahmed, Cathy, McLaren, Rose, Wykes and Burns2009; Jankovic et al. Reference Jankovic, Yeeles, Karsakou, Amos, Morriss, Rose, Nichol, McCabe and Prebe2011). In addition, family members have expressed difficulties with information sharing about patients’ health and treatment due to confidentiality issues, stating this leads to increased tension in their relationship with the treating mental health services (Jankovic et al. Reference Jankovic, Yeeles, Karsakou, Amos, Morriss, Rose, Nichol, McCabe and Prebe2011). A Dutch study evaluated various stakeholders’ perspectives regarding the involuntary admission of their relative with Korsakoff’s syndrome. It noted that stakeholders, despite all wishing to support the patient, had different viewpoints relating to the requirement for their admission and intervention. These different opinions evident between legal professionals, health care professionals and family members led to subsequent tension between the different groups (van den Hooff et al. Reference van den Hooff, Leget and Goossensen2015).

While individual groups of stakeholders have been investigated regarding their views on various operational aspects of the MHA 2001, no study to date has comprehensively examined and compared the views of all stakeholders involved in the operation of the MHA 2001. Consequently, in this study we aimed to evaluate and compare the opinions of all key stakeholders involved in the admission, detention or treatment of patients regarding their experiences of the operation of the MHA 2001. Stakeholders included consultant psychiatrists, nurses, general practitioners, family members, Gardai and legal professionals. Service users were not included in this study, as a separate comprehensive study evaluating their views in depth in relation to the operation of the MHA 2001 is being undertaken.

Methods

Descriptive survey

An interdisciplinary group designed a paper-based and online questionnaire intended to probe attitudes towards the various phases of assessment, admission, treatment and review of involuntary admission. The group consisted of representatives from psychiatry, general nursing, mental health nursing, mental health law, ethics and service users. Questions were phrased in such a way so that the same questions could be answered by the different stakeholders despite their different professional roles and experiences (see Table 2 for a list of the questions). ‘Free-text’ options were included to enable respondents to elaborate on their experiences regarding the operation of the MHA 2001. Initially, the questionnaire included seven items, however, subsequent to free-text responses from GPs, two extra items (Q8 and Q9) regarding patients’ transfer to an approved centre and the use of less restrictive alternative(s) than involuntary admissions to approved centres were added to the questionnaire. An ordinal Likert scale from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’) was employed for each item (see Table 2). GPs and tribunal members completed the original questionnaire only.

Participants

A paper version of the questionnaire was distributed to all consultant psychiatrists (n=19), acute psychiatric nurses (n=71) and CMHNs (n=30) in an Irish sector-based mental health service and to GPs in the associated primary care services (n=205). Similarly, this questionnaire was distributed to all tribunal members attending tribunals at the two approved centres in this region (n=55). In total, 50 patients detained under the MHA 2001 between 1 May 2011 and 31 January 2014 who had engaged in qualitative research with our research team were asked if a preferred family member (first-degree relative) could be contacted and asked to complete the questionnaire, which was then distributed to 33 family members. Gardai Superintendents distributed questionnaires to all Gardai working in the same geographical region (n=609), after consultation and agreement from the Garda Commissioner. The total number of questionnaires distributed was 1022.

To obtain a larger sample of respondents, given the relatively small sample size in some stakeholder groups (especially, consultant psychiatrists and family members), a link to an anonymised online version of the questionnaire (on the online software site Survey Monkey) was then created. This was advertised locally and nationally in Ireland to consultant psychiatrists, acute psychiatric nurses and CMHNs using the authors’ professional networks. The voluntary support group Shine distributed the survey link to family members of service users. Only individuals who had experience with at least one involuntary admission under the MHA 2001 and who provided consent to this research were invited to participate. Incomplete responses from online data (n=42) and respondents who stated that they only had experience with involuntary admissions of patients under the MTA 1945 (n=17), were excluded. Thus, the sample comprised 503 respondents, including 397 paper respondents and 106 online respondents fulfilling the above criteria. The overall response rate for the paper respondents was 39% ranging from 34% for Gardai to 64% for tribunal members (see Table 1). Previous studies on this topic demonstrated similar response rates (Jabbar et al. Reference Jabbar, Doherty, Aziz and Kelly2010; Doherty et al. Reference Doherty, Jabbar and Kelly2014), although one previous study examining GPs opinions regarding the MHA 2001 had higher response rates (Jabbar et al. Reference Jabbar, Kelly and Casey2011). Ethical approval was attained before the commencement of this study from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee for Galway University Hospitals, and the National University of Ireland, Galway.

Statistical analysis

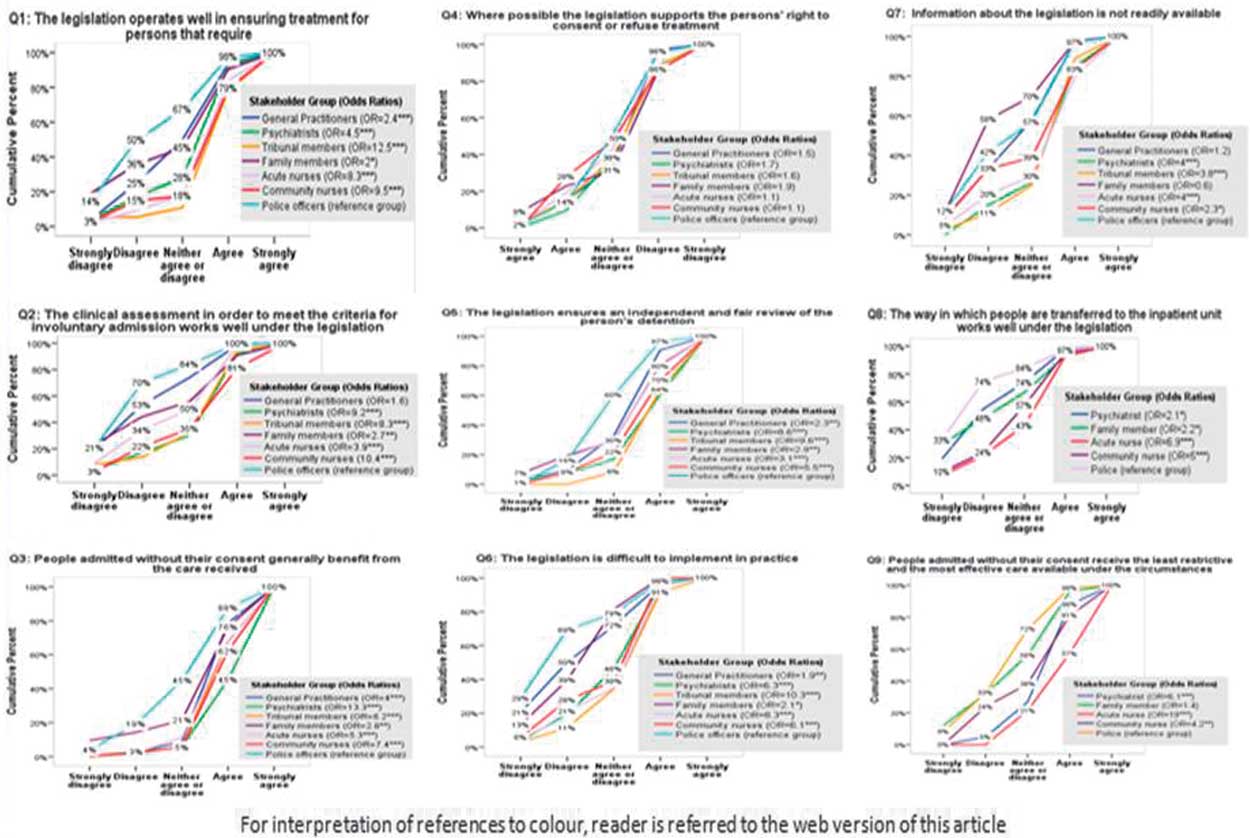

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 20.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., IBM, USA). We utilised the χ 2 test to examine differences in demographic characteristics between groups and post-hoc procedures using adjusted standardised residuals associated with each cell to estimate p values and compare with Bonferroni corrected p values (Beasley & Schumacker, Reference Beasley and Schumacker1995). An ordinal logistic regression model was employed to compare the stakeholders’ views on the operation of the MHA 2001 with ‘stakeholder group’ as the independent variable (McCullagh, Reference McCullagh1980) (Fig. 1) and controlling for gender, age, number of experienced involuntary admissions and type of data collection (paper v. online) (Table 3). Although all group responses are relative, one group needs to be identified as a reference group for this analysis and to express the comparisons as odds ratios. As ‘Gardai’ contained the highest number of respondents, and had answered all items on the questionnaire, they were chosen as the reference group. We employed reverse coding for items 6 and 7 on the questionnaire with high values on these items representing negative attitudes. An alternative analysis of covariance was also utilised to compare stakeholders’ views on the operation of the MHA 2001. Free-text data from both the paper and online questionnaires were examined according to stakeholder group and were open-coded based on the framework of the questionnaire and on any other themes unrelated to these questions that emerged. The data attained from the free-texts was then grouped into themes by consensus of the researchers.

Fig. 1 Cumulative odd ratios of stakeholders regarding views of Mental Health Act (MHA) 2001.

Results

Stakeholders’ demographic details are described in Table 1. There were significant differences between stakeholder groups for age (χ 2=201, df=24, p<0.001), gender (χ 2=39, df=6, p<0.001), number of experienced involuntary admissions (χ 2=171, df=12, p<0.001) and years of professional experience (χ 2=51, df=10, p<0.001).

Table 1 Response rates and demographic characteristics of all stakeholders

CMHNs, community mental health nurses.

Some responders did not provide complete demographic data.

a Response rates were only available for the paper version of the survey. Significant differences between the groups after performing post-hoc analyses are indicated in bold font, p<0.05.

Stakeholders’ responses are outlined in Table 2. Stakeholders expressed greatest satisfaction (agreed or strongly agreed) that patients generally benefit from the care they receive (79%) (Q3) and that the MHA 2001 ensures an independent and fair review of the person’s detention (65%) (Q5). However, only a minority were satisfied (agreed or strongly agreed) with the clinical assessment procedures (37%) (Q2), with the implementation of the MHA 2001 in practice (36%) (Q6) and with the level of information available (34%) (Q7). The process of transfer of patients to the inpatient unit demonstrated the lowest satisfaction rates (23%) with 63% of participants expressing dissatisfaction (disagreed or strongly disagreed) (Q8).

Table 2 Opinions of all stakeholders regarding the Mental Health Act 2001

a Item added after questionnaire distributed to general practitioners and tribunal members.

b Reverse coding was used for these items.

Cumulative odds ratios (with Gardai as the reference group) representing the frequency distributions of stakeholders’ scores per question are presented in Fig. 1 and in Table 3. There was no significant difference among stakeholders’ views regarding the MHA 2001 supporting patients’ right to consent or refuse treatment. Family members and Gardai were most dissatisfied regarding the MHA 2001 operating well to ensure patients receive the treatment they require, regarding the clinical assessment working well under the legislation and regarding the availability of information regarding the MHA 2001. Gardai were also most dissatisfied with the practical implementation of the legislation and with the process of transfer of patients to approved centres, with this dissatisfaction also expressed by psychiatrists and family members. The ANCOVA analysis with gender as a factor and age as a covariate noted similar findings (see supplementary material).

Table 3 Proportional odds model providing cumulative odds ratios for stakeholder groups

CMHNs=community mental health nurses; GPs=General practitioners.

Model controls for all measured variables with reference groups, respectively, Gardai, male gender, age >60, number of experienced involuntary admissions above 20 and paper version.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

There were 421 free-text responses, with the greatest number of these from family members (n=114) (Table 4). Regarding paper data, 130 respondents (36% of participants) gave 184 free-text responses. In total, 237 free-text responses were attained from the 106 online respondents. In total, 10 themes emerged from the free-text responses (Table 4). Themes associated with the greatest free-text response included (1) the transfer of patients to approved centres under the MHA 2001 legislation (n=84), (2) the clinical assessment for involuntary admission under the MHA 2001 (n=70) and (3) that the MHA 2001 ensures treatment for individuals requiring involuntary admission (n=63). Of the 381 free-text responses, only 25 (6.6%) were positive in relation to the operation of the MHA 2001, with the others either clearly negative or partially negative. The process of transferring patients to approved centres was associated with 82 critical comments. These comments (particularly from consultant psychiatrists, GPs, Gardai, CMHNs and family members) highlighted concerns regarding delays in the transfer of patients to approved centres, the lack of local mental health teams to assist with the transfer of patients to approved centres, and the traumatic impact of the transfer process on both patients and family members (Box 1).

Table 4 Themes from various stakeholders comments regarding the operation of Mental Health Act (MHA) 2001

CMHNs=community mental health nurses; GPs=General practitioners.

a Nurses working in approved centres.

Box 1 Sample of free-text responses

AN=acute psychiatric nurse, CMHN=community mental health nurse, CP=consultant psychiatrist, FM=family member, GS=Member of Garda Siochana, TM=tribunal member

The clinical assessment for involuntary admission under the MHA 2001 was associated with 64 comments that expressed concern particularly from Gardai and family members in relation to the time required to organise a clinical assessment, the difficulty in correctly completing MHA 2001 Forms 1–5 with some responses also querying the appropriateness of undertaking a clinical assessment in a Garda station.

There were 50 comments predominantly from Gardai, acute psychiatric nurses and family members expressing concern regarding the MHA 2001 ensuring treatment for individuals that require involuntary admission. Particular concerns related to patients such as those in an intoxicated state from alcohol misuse not meeting criteria for involuntary admission when in distress, that certain patients were admitted for treatment unnecessarily and that the MHA 2001 should facilitate treatment outside of a hospital setting. Several positive comments from psychiatrists, family members and tribunal members indicated that the MHA 2001 succeeded in ensuring treatment for individuals requiring involuntary admission.

Discussion

In the Republic of Ireland, the introduction of the MHA 2001 addressed certain human rights issues disregarded by the previous legislation in relation to individuals with mental disorders, chiefly increasing adherence to international human rights standards regarding involuntary admission and treatment (MHC, 2008; O’Donoghue & Moran, Reference O’Donoghue, Lyne, Hill, O’Rourke, Daly, Larkin, Feeney and O’Callaghan2009; Jabbar et al. Reference Jabbar, Doherty, Aziz and Kelly2010; Jabbar et al. Reference Jabbar, Kelly and Casey2011; Kelly, Reference Kelly2011; Ramsey et al. Reference Ramsey, Roche and O’Donoghue2013).

In this study, we sought to compare opinions of stakeholders involved in the assessment, involuntary admission or treatment of patients regarding their experiences of the operation of the MHA 2001. Similar to previous research with service users, where the majority of patients perceived their involuntary admission as justified and conferring benefit for their mental health difficulties (O’Donoghue et al., Reference O’Donoghue, Lyne, Hill, Larkin, Feeney and O’Callaghan2011), this study demonstrates that other groups of stakeholders involved in the process generally believe that involuntary admission of patients under the MHA 2001 confers benefit to patients. In addition, these stakeholders reported that the MHA 2001 ensures an independent and fair review of patients’ detention and supports their right to consent or refuse treatment, which is in keeping with findings related to the MHAs in other European countries (Fiorillo et al. Reference Fiorillo, De Rosa, Del Vecchio, Jurjanz, Schnall and Onchev2011).

However, substantial dissatisfaction with several aspects of the operation of the MHA 2001 was expressed. These areas of dissatisfaction largely concern service related rather than legislative elements of the Act. The area of greatest dissatisfaction related to the process of patients’ transfer to approved centres under the MHA 2001. Gardai, family members and psychiatrists expressed substantial concerns via the questionnaire, with this view also expressed by all stakeholder groups in their free-text responses. Particular concern related to the organisation and duration of time required for transferring a patient to an approved centre, particularly if a local assisted admission team is not utilised, leading to additional distress for patients and other stakeholders involved. Patients are often transferred to approved centres from their own homes. A previous study noted concern from GPs in relation to the time required to organise patient transfer to approved centres and the distress this can cause to patients (Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, O’Sulliva, Finnegan, Moran and Bradley2011). This study demonstrates that such a concern is shared across other stakeholder groups. One potential reason for difficulty in transferring patients to approved centres is the increased use of out-sourced assisted admission teams rather than local staff, who are unfamiliar with the person and also often require substantially more time to reach the patient. This study provides support for the use of local mental health staff known to the patient, where this is possible, for the transfer of patients to an approved centre.

This is the first study to evaluate the opinions of the Gardai in relation to the operation of the MHA 2001 and demonstrates that Gardai are dissatisfied with several aspects of the operation of the MHA 2001. In addition to concerns regarding the transfer of patients to approved centres, Gardai consistent with other stakeholders, expressed concern regarding ‘paperwork’ or ‘excessive legalities’ (Jabbar et al. Reference Jabbar, Kelly and Casey2011; Doherty et al. Reference Doherty, Jabbar and Kelly2014). Free-text comments suggested that many Gardai were concerned with the appropriateness of clinical assessments being undertaken in a Garda station. Gardai, in particular, expressed dissatisfaction with the availability of information and training (questionnaire and free-text responses). Perhaps dedicated training for Gardai in particular may alleviate some of this concern. The EUNOMIA study examined service user’s perspectives of involuntary admission across 11 European countries (not including Ireland) and recommended police involvement only when all other alternatives have been exhausted. Furthermore, it recommended appropriate training for police regarding both clinical aspects of the main mental health disorders and concerning the legal and administrative aspects of the MHA legislation (Fiorillo et al. Reference Fiorillo, De Rosa, Del Vecchio, Jurjanz, Schnall and Onchev2011).

Despite the presence of the authorised officers function in the MHA 2001, family members still initiate the majority of involuntary admission orders (MHC, 2014). Consistent with our findings, previous studies have also demonstrated that the application process to a registered medical practitioner for a recommendation for involuntary admission of a relative (Form 1) negatively impacts on the relationship with a family member. These difficulties have been shown to persist 1 year after an involuntary admission (O’Donoghue et al., 2010). Of note, the Expert Group reviewing the operation of the MHA 2001 recommend that there should be a more expanded and active role for Authorised Officers, including accessibility to Authorised Officers 7 days a week (Department of Health, 2015). The current study provides further support from stakeholders’ views for the implementation in practice of the Authorised Officer assessments, which are already provided for in legislation.

Family members expressed greater dissatisfaction regarding care in hospital benefiting their relative and the review process of their relatives’ detention being fair, compared with other stakeholders such as psychiatrists and tribunal members. Potentially, this may reflect family members having limited involvement in their relative’s care after they are admitted to an approved centre and that they usually have no role in the tribunal process. Previous research has identified that family members would like more information regarding the progress of their relative in hospital (Jankovic et al. Reference Jankovic, Yeeles, Karsakou, Amos, Morriss, Rose, Nichol, McCabe and Prebe2011). This study supports the need for more extensive psycho-education and engagement of family members throughout their relatives’ admission and suggests that it might be desirable if family members were more regularly invited to attend mental health tribunals with the patients’ consent.

Strengths of the study include the large number of respondents surveyed and the utilisation of the same questionnaire across several stakeholder groups, which enabled comparisons between views of stakeholders who have different roles in the process of involuntary admission and differential views exposed. There are a number of limitations with this study, however, including the lack of a validated questionnaire, the fact that Gardai and GPs completed a shorter version of the questionnaire and the relatively low response rate of Gardai. There are also a number of potential biases. One mental health-based service was over-represented as paper questionnaires were only distributed in that location. Individuals who chose to make a free-text response(s) were self-selected. Furthermore, interpretation of free-text comments may also be biased, as researchers were not in a position to explore meaning with participants. Nor could researchers probe in further detail what solutions stakeholders might propose to improve their satisfaction with the operation of the Act.

Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the experiences of key stakeholders involved in the provision of involuntary admission and treatment under the MHA 2001, and highlights areas where difficulties exist. The MHA 2001 facilitates provision of care to patients who lack capacity to make decisions about their own admission and treatment, and are often in situations of extreme distress for themselves and their carers. The study demonstrates that some key components of the legislation, providing care and respecting rights are usually achieved in practice according to stakeholders. However, substantial process difficulties for stakeholders appear to exist in the implementation of the MHA 2001, particularly at that most distressing period of clinical assessment and transfer to hospital with the stakeholders involved in this aspect of the process expressing highest levels of dissatisfaction. While no system will meet with universal approval across all stakeholders, additional service-related supports are likely to improve the negative experiences for stakeholders, especially during the critical phase of assessment and transfer of patients to hospital. These include increased training and information, support and resources, particularly in relation to funding Authorised Officers, local assisted admission services and carer support workers. Such resources require no additional legislative change but are of potentially substantial benefit to patients and key stakeholders.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Mental Health Commission for funding this study and all respondents who completed the questionnaires. The authors also wish to thank Shine and Gardai superintendents for distributing the questionnaire. The authors wish to thank John Newell, Senior Lecturer in Statistics, Clinical Research Facility, NUI Galway for his statistical input.

Financial Support

This work was supported by a research grant received from the Mental Health Commission: Research Programme Grants in Mental Health Services Research, 2011–2016.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1017/ipm.2016.6