1 Introduction

In the past decades dozens of psychological interventions for the treatment of depression have been developed. However, only a relatively small number of these treatments have been tested in ten or more randomized trials. The therapies that have been well-examined include cognitive behavior therapy [Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Andersson, Beekman and Reynolds1, Reference Churchill, Hunot, Corney, Knapp, McGuire and Tylee2], interpersonal psychotherapy [Reference Cuijpers, Geraedts, van Oppen, Andersson, Markowitz and van Straten3, Reference Cuijpers, Donker, Weissman, Ravitz and Cristea4], behavioral activation [Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and Warmerdam5, Reference Ekers, Richards and Gilbody6], brief psychodynamic therapy [Reference Driessen, Hegelmaier, Abbass, Barber, Dekker and Van7, Reference Leichsenring and Rabung8] and non-directive counseling Reference Cuijpers, Driessen, Hollon, van Oppen, Barth and Andersson[9]. When considering the several hundreds of randomized controlled and comparative trials that have examined psychotherapies for depression, it has become clear that these therapies have modest but clinically relevant effects Reference Cuijpers, Turner, Koole, van Dijke and Smit[10]. Furthermore, this area of research has shown that there are no major differences between the effects of these treatments Reference Barth, Munder, Gerger, Nuesch, Trelle and Znoj[11], that these treatments can be delivered effectively in individual, group, guided self-help and internet-delivered format [Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and Warmerdam12–Reference Cuijpers, Donker, Johansson, Mohr, van Straten and Andersson14], and that they are effective in several different target groups, such as older adults [Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Smit and Andersson15, Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and Smit16], children and adolescents Reference Weisz, Kuppens, Eckshtain, Ugueto, Hawley and Jensen-Doss[17], postpartum depression Reference Cuijpers, Brannmark and van Straten[18], college students Reference Cuijpers, Cristea, Elbert, Koot, Auerbach and Bruffaerts[19], and patients with comorbid general medical disorders Reference van Straten, Geraedts, Verdonck-de Leeuw, Andersson and Cuijpers[20].

One of the interventions that has been tested as a treatment of adult depression in a considerable number of randomized trials is problem-solving therapy (PST). PST was developed in the 1970s as one of the first treatments of depression Reference D’zurilla and Goldfried[21], and was first tested in the 1980s [Reference Nezu22, Reference Nezu and Perri23]. PST focuses on training in adaptive problem-solving attitudes and skills and is aimed at reducing and preventing psychopathology, and at enhancing positive well-being by helping individuals cope more effectively with stressful problems in daily life Reference Bell and D’Zurilla[24].

A decade ago we conducted a meta-analysis of trials testing the effects of PST for adult depression Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and Warmerdam[25]. The 13 trials that were included in this meta-analysis pointed at a large effect of PST versus control groups (d = 0.83), and some indications were found that PST was more effective than other therapies, although that was based on a small set of studies. Since this meta-analysis, several other meta-analyses have been published [Reference Bell and D’Zurilla24, Reference Malouff, Thorsteinsson and Schutte26, Reference Kirkham, Choi and Seitz27]. However, the last comprehensive meta-analysis aimed at including all trials on PST for depression was published in 2009 Reference Bell and D’Zurilla[24]. One meta-analysis was published later Reference Kirkham, Choi and Seitz[27], but that was only aimed at studies among older adults. Because the number of trials on PST has more than doubled since then, a new meta-analysis is much needed. Furthermore, none of the comprehensive meta-analyses examined the effects of the quality of the included trials on the outcomes, nor was publication bias well examined.

Another reason why a new meta-analysis of PST is useful, is that in our first meta-analysis a very high level of heterogeneity was found, indicating that the effect sizes varied strongly across studies Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and Warmerdam[25]. It was not possible to identify possible causes of this heterogeneity in subgroup and meta-regression analyses. It is important, however, to know under which conditions PST has large or small effects. Because the number of trials is now considerably larger than 10 years ago, it may be possible to better identify possible causes of heterogeneity.

We conducted a new meta-analysis of PST for adult depression. We wanted to examine the overall effects of PST, the level of heterogeneity and to conduct subgroup and meta-regression analyses to examine potential causes of this heterogeneity. Furthermore, we wanted to examine the relative effects of PST compared with other psychological therapies. We wanted to examine this from trials directly comparing PST with other therapies, but also by comparing the effects found in trials comparing PST with control groups, with the effects found for other therapies that are compared with control groups.

2 Methods

2.1 Identification and selection of studies

We used an existing database of studies on the psychological treatment of depression. This database has been described in detail elsewhere Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Warmerdam and Andersson[28], and has been used in a series of earlier published meta-analyses Reference Cuijpers[29]. For this database we searched four major bibliographical databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase and the Cochrane Library) by combining terms (both index terms and text words) indicative of depression and psychotherapies, with filters for randomized controlled trials. The full search string for one database (PubMed) is given in Appendix A in Supplementary material. We also searched a number of bibliographical databases to identify trials in non-Western countries Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders, Purgato and Barbui[30], because the number of trials on psychological treatments in these countries is growing rapidly. Furthermore, we checked the references of earlier meta-analyses on psychological treatments of depression. The database is continuously updated and was developed through a comprehensive literature search (from 1966 to January 1st, 2017). All records were screened by two independent researchers and all papers that could possibly meet inclusion criteria according to one of the researchers were retrieved as full-text. The decision to include or exclude a study in the database was also done by the two independent researchers, and disagreements were solved through discussion.

We included studies that were: (a) a randomized trial (b) in which PST (c) for adult depression was (d) compared with a control group (waiting list, care-as-usual, placebo, other inactive treatment) or another treatment (psychological or pharmacological). Depression could be established with a diagnostic interview or with a score above a cut-off on a self-report measure. Co-morbid mental or somatic disorders were not used as an exclusion criterion. Studies on inpatients were excluded. We also excluded maintenance studies, aimed at people who had already recovered or partly recovered after an earlier treatment. We considered an intervention to be PST when problem-solving was the core element of the intervention that was meant to reduce depression. Other techniques were allowed when they were aimed at supporting or strengthening the problem-solving element. If other techniques were clearly considered to be separate elements, we did not consider it PST.

In addition to the main analyses in which we focused on the studies on PST, we also wanted to compare the effects of PST with the effects found for other psychological treatments of adult depression. For this comparison we selected trials from our database in which other types of psychotherapy for depression were compared with a control condition, with the same in- and exclusion criteria as for the studies on PST.

2.2 Quality assessment and data extraction

We assessed the validity of included studies using four criteria of the ‘Risk of bias’ assessment tool, developed by the Cochrane Collaboration Reference Higgins, Altman, Gøtzsche, Jüni, Moher and Oxman[31]. This tool assesses possible sources of bias in randomized trials, including the adequate generation of allocation sequence; the concealment of allocation to conditions; the prevention of knowledge of the allocated intervention (masking of assessors); and dealing with incomplete outcome data (this was assessed as positive when intention-to-treat analyses were conducted, meaning that all randomized patients were included in the analyses). Assessment of the validity of the included studies was conducted by two independent researchers, and disagreements were solved through discussion.

We also coded participant characteristics (depressive disorder of scoring high on a self-rating scale; recruitment method; target group); characteristics of the psychotherapies (treatment format; number of sessions); and general characteristics of the studies (type of control group; country where the study was conducted). Treatment format was coded as individual, group or guided-self help (including internet-based guided self-help).

We distinguished three types of PST Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and Warmerdam[25]: (1) Extended PST, which does not only focus on the problem-solving skills themselves, but also on changing those attitudes or beliefs that may inhibit or interfere with attempts to engage in the remaining problem-solving tasks. It is typically conducted in a group format of 10 or more sessions. We (arguably) considered an intervention as extended PST when it had 10 sessions or more. (2) Brief PST, which was originally developed for primary care (PST-PC), focuses on the core elements of problem-solving and can be used by trained nurses. We considered an intervention as brief PST when it had 9 sessions or less. (3) Self-examination therapy (SET) is aimed at determining the major goals in their life, investing energy only in those problems that are related to what matters and learning to accept those situations that cannot be changed. Problem-solving skills are the core element of this approach. SET is typically used in a guided-self-help format. We considered an intervention as SET when it was based on self-examination therapy Reference Bowman, Ward, Bowman and Scogin[32] and was conducted in guided self-help format.

In the studies comparing PST with other therapies we also examined researcher allegiance, using the methods we have described before Reference Cuijpers, Driessen, Hollon, van Oppen, Barth and Andersson[9]. We coded that researcher allegiance was in favor of PST (against the alternative therapy) if: (1) PST was the only therapy mentioned in the title; (2) PST was explicitly mentioned as the main experimental intervention in the introduction section of the study; (3) the alternative therapy was explicitly described as a control condition included to control for the non-specific components of the comparison therapy; or (4) there was an explicit hypothesis that PST was expected to be more effective than the alternative therapy.

2.3 Outcome measures

For each comparison between PST (or another type of psychotherapy) and a control condition, the effect size indicating the difference between the two groups at post-test was calculated (Hedges’ g). Effect sizes of 0.8 can be assumed to be large, while effect sizes of 0.5 are moderate, and effect sizes of 0.2 are small Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman[33]. Effect sizes were calculated by subtracting (at post-test) the average score of the psychotherapy group from the average score of the control group, and dividing the result by the pooled standard deviation. Because some studies had relatively small sample sizes we corrected the effect size for small sample bias Reference Duval and Tweedie[34]. If means and standard deviations were not reported, we used the procedures of the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (see below) to calculate the effect size using dichotomous outcomes; and if these were not available either, we used other statistics (such a t-value or p-value) to calculate the effect size.

In order to calculate effect sizes we used all measures examining depressive symptoms (such as the Beck Depression Inventory/BDI Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh[35]; the BDI-II Reference Beck, Steer and Brown[36]; or the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression/HAMD-17 Reference Hamilton[37]).

2.4 Meta-analyses

To calculate pooled mean effect sizes, we used the computer program Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 3.3070; CMA). Because we expected considerable heterogeneity among the studies, we employed a random effects pooling model in all analyses.

Numbers-needed-to-be-treated (NNT) were calculated using the formulae provided by Furukawa Reference Furukawa[38], in which the control group’s event rate was set at a conservative 19% (based on the pooled response rate of 50% reduction of symptoms across trials in psychotherapy for depression) Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Weitz, Andersson, Hollon and van Straten[39]. As a test of homogeneity of effect sizes, we calculated the I2-statistic, which is an indicator of heterogeneity in percentages. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values indicate increasing heterogeneity, with 25% as low, 50% as moderate, and 75% as high heterogeneity Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman[33]. We calculated 95% confidence intervals around I2 Reference Ioannidis, Patsopoulos and Evangelou[40], using the non-central chi-squared-based approach within the heterogi module for Stata Reference Orsini, Bottai, Higgins and Buchan[41]. We conducted sensitivity analyses excluding potential outliers. These were defined as studies of which the 95% CI of the effect size did not overlap with the 95% CI of the pooled effect size.

We conducted subgroup analyses according to the mixed effects model, in which studies within subgroups are pooled with the random effects model, while tests for significant differences between subgroups are conducted with the fixed effects model. For continuous variables, we used meta-regression analyses to test whether there was a significant relationship between the continuous variable and effect size, as indicated by a Z-value and an associated p-value. Multivariate meta-regression analyses, with the effect size as the dependent variable, were conducted in CMA.

We tested for publication bias by inspecting the funnel plot on primary outcome measures and by Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure Reference Duval and Tweedie[34], which yields an estimate of the effect size after the publication bias has been taken into account (as implemented in CMA). We also conducted Egger’s test of the intercept to quantify the bias captured by the funnel plot and to test whether it was significant.

3 Results

3.1 Selection and inclusion of studies

After examining a total of 18,500 abstracts (14,290 after removal of duplicates), we retrieved 2,092 full-text papers for further consideration. We excluded 1,827 of the retrieved papers. The PRISMA flowchart describing the inclusion process, including the reasons for exclusion, is presented in Fig. 1. A total of 30 studies on PST met inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis (Table 1).

Another 264 studies (with 342 comparisons between a treatment and a control group) on psychological treatments other than PST were included (for the comparison of effect sizes of PST with those of other psychological treatments). This makes a total of 290 studies that were included in the analyses.

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

Selected characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. In the 30 included studies on PST (with 12 comparisons between PST and another therapy condition, and 27 comparisons between PST and a control condition), a total of 3,530 patients participated (PST conditions = 1,576, other therapy conditions = 542, control conditions = 1,412). Participants were recruited through: (a) announcements in local newspapers and other media (12 studies), (b) referrals from health services (eight studies), (c) other recruitment strategies (such as screening at general medical services; nine studies), and one study did not report the recruitment strategy. In total, 14 studies were targeted at adults, eight were targeted at elderly adults, two were targeted at ethnic minorities, four were targeted at adults with a general medical disorder, one at adult caregivers, and one was targeted at women with postpartum depression. Brief PST was used in 15 studies, Extended PST was used in 10 studies, and Self-Examination PST was used in five studies).

In three of the comparisons between PST and another therapy condition, cognitive behavior therapy was used as the comparator, two used behavioural activation therapy, one used case management, three used non-directive supportive therapy, one used referral, one used reminiscence, one used social skills training, and one used stress management. Seven studies used a group treatment format, 16 studies utilized individual treatment, five used a guided self-help treatment format, and two studies used another format. The number of treatment sessions ranged from four to 12. For the control group, 12 studies used a waiting list, seven studies used care-as-usual, five studies used antidepressant medication, three studies used placebo, and one study used another control group. 18 studies were conducted in North America, 11 were conducted in Europe, and one was conducted in Africa.

Selected characteristics of the 264 studies on psychotherapies other than PST (with 342 comparisons between treatment and control groups) are presented in Appendix B in Supplementary material and the references for these studies are given in Appendix C in Supplementary material.

3.3 Risk of bias

The risk of bias in most of the studies on PST was considerable. A total of 14 of the 30 studies reported an adequate sequence generation (47%). Thirteen studies reported allocation to conditions by an independent (third) party (43%). Ten studies reported using blinded outcome assessors (33%), and 16 used only self-report outcomes. In 16 studies intent-to-treat analyses (completeness of follow-up data) were conducted (53%). Only seven studies (23%) met all quality criteria. 12 studies (40%) met two or three of the criteria and the 11 remaining studies met no or only one criterion.

Fig. 1 Flowchart for the inclusion of studies.

3.4 Effects of PST compared with control groups

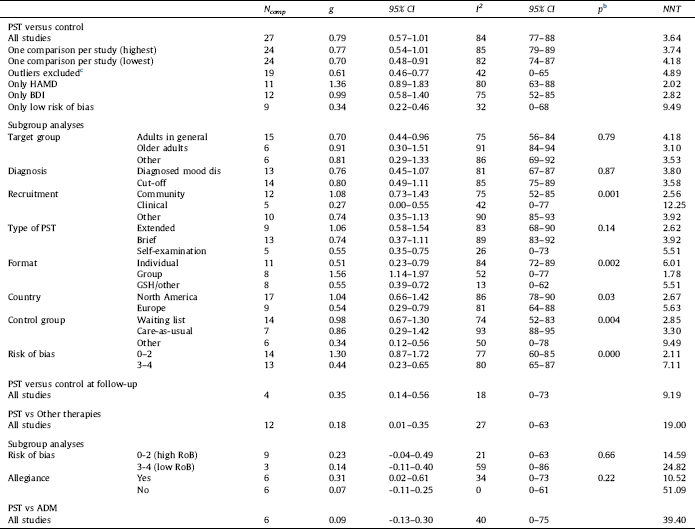

We could compare the effect of PST with control groups in 27 comparisons. The overall effect size was g = 0.79 (95% CI: 0.57–1.01), which corresponds with a NNT of 3.64. Heterogeneity was very high (I2 = 84; 95% CI: 77–88). The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 2. The effect sizes for each study are presented in the forest plot in Fig.2.

In three studies ([Reference Nezu22, Reference Nezu and Perri23, Reference Choi, Marti, Bruce and Hegel42]; see Table 1), two types of therapies that met our definition of PST were compared with the same control group. Because these effect sizes were not independent of each other, they may have artificially reduced heterogeneity and influenced the effect sizes. We conducted two separate analyses to examine this. In the first analysis we only included the largest effect size from each study, and in the second only the smallest effect size. As can be seen in Table 2, the effect sizes and levels of heterogeneity were comparable to those in the main analyses. When we limited the effect sizes to those based on the HAM-D and the BDI (the most used instruments), we found that the effect sizes were larger than those found in the overall analyses, especially for the HAM-D. Levels of heterogeneity remained comparable.

We found strong indications for publication bias (Fig. 3). Duvall and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure suggested that 10 studies were missing and after imputation of these studies the effect size dropped from g = 0.79 to g = 0.39 (95% CI: 0.14–0.64). Egger’s test of the intercept also pointed at considerable publication bias (intercept: 3.32; 95% CI: 1.46–5.17; p < 0.001).

In order to generate the best estimate of the true effect size, we selected the studies with low risk of bias (9 comparisons; g = 0.34; 95% CI: 0.22–0.46; NNT = 9.49; I2 = 32; 95% CI: 0–68), and adjusted that for publication bias. The resulting effect size was g = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.14–0.42; number of imputed studies: 2), which corresponds with a NNT of 11.77.

Table 1 Selected characteristics of studies examining problem solving therapy for adult depression (N = 3.357).

Note: Abbr.: Abbreviated; ADM: Anti-depressant Medication; BA: Behavioral Activation; Brf: Brief; CAU: Care as Usual; CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Clin: participants recruited in a clinical setting; Comm: participants recruited in a community setting; CT: Cognitive Therapy; Diagn: Diagnosis; EU: Europe; Ext: Extended; ftf: Face-to-face; GP: General Practitioner; Grp: group format; Gsh: guided self-help format; Ind: individual format; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; Med. Dis.: Medical Disorder; Nsess: Number of sessions; Pf: Problem-Focused; PPD; Post-Partum Depression; Recr: Recruitment; RoB: Risk of Bias; SET: Self-Examination Therapy; SST: Social Skills Training; SUP: Nondirective Supportive Therapy; tel: Telephone; WL: Waitlist.

a In this column a positive (+) or negative (−) sign is given for four quality criteria of the study, respectively: allocation sequence; concealment of allocation to conditions; blinding of assessors; and intention-to-treat analyses. Sr in the third criterion indicates that only self-report measures (and no assessor) were used.

Fig. 2 Forrest plot of effect sizes from randomized controlled trials on problem-solving therapy for adult depression.

Only three studies (4 comparisons) examined the effects of PST versus control groups at the longer term, one (with two comparisons) at 6 months and two at 12 months follow-up. However, only one of these studies had low risk of bias. The pooled effect size was g = 0.35 (95% CI: 0.14–0.56; I2 = 18; 95% CI: 0–73; NNT = 9.19).

3.5 Subgroup and meta-regression analyses

In order to examine possible sources of heterogeneity, we conducted a series of subgroup analyses (Table 2). We found several significant differences between subgroups. Studies in which patients were recruited from the community resulted in significantly higher effect sizes than studies among patients from clinical samples and patients that were recruited in other ways (p = 0.001). Group treatments resulted in higher effect sizes than individual, and guided self-help treatments (p = 0.002). Studies conducted in North America had considerably higher effect sizes than studies from Europe (p = 0.03). Studies with a waiting list control condition had higher effect sizes than studies with a care-as-usual or another control group (p = 0.004), and studies with low risk of bias had lower effect sizes than studies with high risk of bias (p < 0.001). We found no indication that target group, diagnosis or type of PST were significantly related to the effect size.

Because there were several studies with very high effect sizes, which may have distorted these subgroup analyses, we repeated the analyses while excluding studies with effect sizes larger than g = 1.5. We found that the results were overall very comparable, and all significant subgroup analyses remained significant, except for the difference between effect sizes in North-American and Europe.

We also conducted a multivariate regression analysis (with the effect size as dependent variable) in which all variables of the subgroup analyses were simultaneously entered as predictors. All variables were entered as categorical variables, except risk of bias that was entered as a continuous variable. We also added the number of treatment sessions as continuous variable. In these analyses none of the predictors remained significantly associated with the effect size.

Fig. 3 Funnel plot of standard error by Hedges g.

In order to avoid overfit of the meta-regression model, we repeated this meta-regression analysis, with a (manual) stepwise backward elimination of the least significant predictor until only significant predictors remained in the model. This analysis resulted in only one significant predictor, namely risk of bias (coefficient: −0.26, SE: 0.09, p = 0.008). Higher risk of bias resulted in larger effect sizes.

3.6 Direct comparisons of PST versus other treatments

We could compare PST with another type of psychotherapy in 12 comparisons. We found a significant effect size indicating superior effects of PST compared with other therapies at post-test, with g = 0.18 (95% CI: 0.01–0.35; NNT = 19.00). Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 27; 95% CI: 0–63).

Because the number of studies was so small we only conducted two subgroup analyses. In the first subgroup analyses we examined whether the effects in studies with high risk of bias were different from those with low risk of bias. The effect sizes in the two groups of studies did not differ significantly, possibly because of low statistical power related to the small number of studies with low risk of bias. Both subgroups resulted in a small, non-significant differential effect size.

In the second subgroup analysis we compared studies with researcher allegiance to those without. The difference between the subgroups was not significant, but the five studies without allegiance did not result in a significant difference between PST and other therapies.

We could compare PST with antidepressant medication in 6 comparisons. We found no significant difference between the two (g = 0.09; 95% CI: −0.13–0.30). Because of the small number of studies we did not conduct further analyses.

3.7 Controlled trials on PST versus controlled trials on other psychotherapies

We compared the 27 comparisons between PST and a control condition to the 342 comparisons of other psychotherapies versus control conditions, and found no significant difference (other therapies: g = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.64–0.74; I2 = 75; 95% CI: 72–78; NNT = 4.25; p for difference with PST: 0.50).

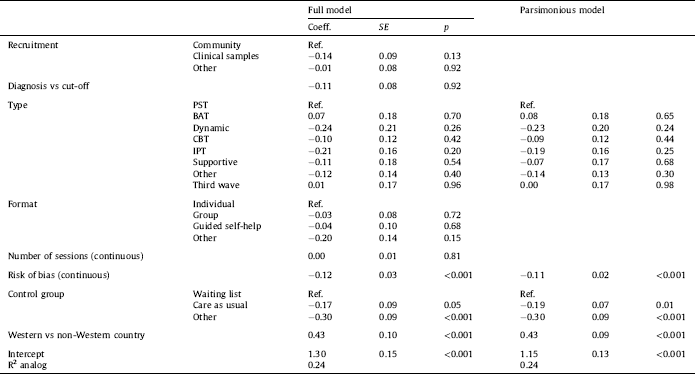

Then we conducted a multivariate meta-regression analysis in which we included type of therapy as well as other characteristics of the participants, the therapies and the studies as predictor in the model. The results are presented in Table 3 (full model). As can be seen, there was no indication that the effect size found for PST differed from the effect sizes of other therapies after adjustment for the other characteristics of the participants, therapies and studies.

We conducted again another multivariate metaregression analysis with a (manual) stepwise backward elimination of the least significant predictor until only significant predictors remained in the model (except type of therapy that was not removed from the model, because this was the variable of interest). The same variables that were significant in the full model were also significant in the parsimonious model, and there was no indication that PST differed significantly from the other types of therapy.

4 Discussion

In this updated meta-analysis of PST for adult depression we found an overall large effect of PST compared to control conditions. However, a better estimate of the true effect size, based on studies with low risk of bias and after adjustment for publication bias pointed at a small effect of PST. This is in line with research on other treatments of depression, such as cognitive behavior therapy Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Andersson, Beekman and Reynolds[1] and interpersonal psychotherapy Reference Cuijpers, Donker, Weissman, Ravitz and Cristea[4], where overall large effects are found but much smaller ones in high-quality studies and after adjustment for publication bias [Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Bohlmeijer, Hollon and Andersson43, Reference Cuijpers, Smit, Bohlmeijer, Hollon and Andersson44].

Direct comparisons of PST with other types of psychotherapy showed a small significant effect in favor of PST. However, in a considerable number of studies (more than half of the 11 trials) we found indications for researcher allegiance in favor of PST. These findings should therefore be considered with caution. A comparison of trials on PST versus control groups and the large number of trials on other therapies versus control groups, also indicated no significant difference between PST and other therapies. Furthermore, no differential effect of any of the other types of therapy was found, suggesting that all therapies are equally or about equally effective. This is also in line with several previous large meta-analyses showing no or only small differences between therapies for depression [Reference Barth, Munder, Gerger, Nuesch, Trelle and Znoj11, Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Warmerdam and Andersson28].

Table 2 Effects of problem-solving therapy compared with control groups and other treatments: Hedges’ g.

Abbreviations: ADM: Anti-Depressant Medication; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CI: Confidence interval; GSH: Guided Self-Help; HAMD: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; Ncomp: number of comparisons; NNT: Numbers-needed-to-treat; PST: Problem Solving Therapy; RoB: Risk of Bias.

a according to the random effects model.

b The p-values in this column indicate whether the difference between the effect sizes in the subgroups is significant.

c Outliers were: Alexopoulos, 2016; Barret, 2001; Dowrick, 2000; Gellis, 2010; one of the comparisons from Nezu et al., 1986; one of the comparisons from Nezu et al., 1989; Vazquez, 2013; Williams et al., 2000.

We also found that the set of high-quality studies resulted in a low level of heterogeneity, although there was still some uncertainty around this low level. But overall this set of high-quality studies was consistent in pointing a small effect size, with no large deviations from that. Most of the heterogeneity was introduced by the studies with low or uncertain quality, which resulted in levels of heterogeneity of up to 80%. This in line with our previous meta-analysis on problem-solving Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and Warmerdam[25], where we also found a high level of heterogeneity, but could not find explanations for that in subgroup analyses. The number of high-quality studies was too small to examine whether their characteristics differed from studies of lower-qualities.

We found no significant difference between the three types of PST that we examined. However, the extended PST with 10 or more sessions did result in a considerably larger effect size, although that difference was not significant. The difference between extended and the other two types of PST may not have reached significance because of low statistical power. We had certainly too little power to examine a possible difference between the three types in high-quality studies. So it remains uncertain whether there is difference between these types of PST.

In the draft NICE treatment guidelines for depression [45] PST is not considered as a separate type of treatment and is included in the broader “family” of cognitive behavioral therapies, together with rational emotive behavior therapy and third-wave therapies. Although we do think that PST can be seen as a member of a broader “family” of cognitive behavioral therapies, we think this can be easily disputed. Cognitive restructuring is typically considered to be the core of cognitive behavioral therapies or at least one of the core elements. In PST, however, problem solving skills are the core of the treatment, and cognitive restructuring is not included in most of the PST manuals. We think therefore, that the NICE guidelines have missed an opportunity to examine the contribution of PST to treatments of depression. Because PST is included in cognitive behavioral therapy there is a risk that clinicians will be inclined not to use it anymore, while it still is one of the best examined therapies for depression.

Table 3 Standardized regression coefficients of characteristics of studies on problem solving therapy and other psychological treatments of adult depression: Multivariate metaregression analyses.

Abbreviations: BAT: Behavioral Activation Therapy; CBT: Cognitive Behavior Therapy; Coeff: Regression Coefficient; HAMD: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IPT: Interpersonal Psychotherapy; p: this p-value indicates whether the regression coefficient of the subgroup differs significantly from the reference group; PST: Problem Solving Therapy; Ref: Reference group; SE: Standard Error.

This study had several limitations. The most important one is that we could include only a relatively small sample of studies, and less than 10 studies of high-quality. This resulted in low power to examine the effects and moderators of the effects of PST. Another limitation is that hardly any study examined the long-term effects of PST. We also found considerable indications for publication bias. And in the studies comparing PST with other psychotherapies we found researcher allegiance in more than half of the studies, affecting the value of these studies.

Despite these limitations we can conclude that PST is probably an effective treatment of depression, with effect sizes that are small, but comparable to those found for other psychological treatments of depression.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

No grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors was received for this study.

Acknowledgements

None.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.11.006.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.