4.1 Introduction

The term ‘primary health care’ (PHC) has been operationalised in a variety of ways since it was first coined as part of the historic Alma Ata Declaration (Box 4.1). In this chapter, we operationally define PHC to cover the ‘first level of contact of individuals, the family and community with the national health system’ and ‘reflect(s) and evolve(s) from the economic conditions and sociocultural and political characteristics of the country’. The elements of PHC we will focus on include ‘education concerning prevailing health problems, … maternal and child health care including family planning and immunization, and appropriate treatment of common diseases and injuries’. Other aspects of PHC, such as safe water and basic sanitation, prevention and control of locally endemic diseases, and provision of essential drugs, are covered in other chapters.

Box 4.1 Excerpts from the Declaration of the Alma Ata International Conference on Primary Health Care, September 1978

Primary health care is essential health care … made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford.

It is the first level of contact of individuals, the family and community with the national health system … and constitutes the first element of a continuing health care process.

Involves, in addition to the health sector, all related sectors and aspects of national and community development, in particular agriculture, animal husbandry, food, industry, education, housing, public works, communications and other sectors; … and demands the co-ordinated efforts of all those sectors.

Sustained by integrated, functional and mutually supportive referral systems, leading to the progressive improvement of comprehensive health care.

This chapter explores the development of PHC during the 60-year period after Malaysia achieved independence (1957–2018). The development process is viewed in the context of the interaction of various components of the health system, as well as the interactions with other sectors and the influence of international movements. Two distinct phases of development are evident, as described in Sections 4.2 and 4.3.

4.2 The First Phase of PHC Development (1960s–1990s)

4.2.1 Drivers and Contexts

At independence, about 75% of the population lived in rural areas, and almost half the population lived in poverty (Reference Mohd Ashad and ShamsudinMohd Ashad & Shamsudin, 1997). The ethnic composition reflected the urban–rural divide, with ethnic Malays being largely rural, ethnic Chinese largely urban and ethnic Indians largely in the rubber estates. Maternal and child mortality was high, nutritional status was poor and the incidence of infectious diseases was high. Table 4.1 provides a glimpse of Malaysia’s health status at independence and its evolving status during the subsequent 30 years.

Table 4.1 Health indicators in Malaysia, 1957–1990

| 1957 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy at birth, male (years) | 55.8 | 61.6 | 66.4 | 68.9 |

| Life expectancy at birth, female (years) | 58.2 | 65.6 | 70.5 | 73.5 |

| Maternal mortality ratio per 1,000 live births | 2.81 | 1.62 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births | 73.01 | 43.82 | 23.8 | 13.1 |

| Toddler mortality rate per 1,000 population aged 1–4 years old | 8.91 | 5.02 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

1 1956–1960

2 1966–1970

The PHC system developed for Malaysia was built on the healthcare system inherited from the British colonial system. It consisted of outpatient clinics attached to hospitals, a few dispensaries and infant welfare centres provided by the government, and private sector clinics operated by doctors (general practitioners, or GPs). Almost all of these services were in urban areas. This healthcare system evolved from the requirements of the expatriate governing staff, that is, the more educated and affluent urban population.

The predominantly rural population depended on practitioners of traditional medicine, while workers in the larger rubber estates depended on estate clinics provided by employers. However, four years prior to independence, the country introduced a service to serve the rural population, which evolved into the Rural Health Service (RHS) in 1956, just before Malaysia gained independence (Reference RudnerRudner, 1972; Reference IsmailIsmail, 1974; Reference Wong, Ng and SuJ. H. W. Wong et al., 2019).

Independence brought into power an elected coalition of ethnically based political parties, led by the ethnic Malay political party. Unsurprisingly, the political focus shifted to prioritise rural communities to reflect the location of strong Malay support. The major thrust of development was to achieve socio-economic transformation by developing the country’s basic rural infrastructure, modernising agricultural production in rural areas and improving education and health (Federation of Malaya, 1960; Reference RudnerRudner, 1972; Reference Lee and LeeLee & Lee, 2017). Infrastructure development was an integrated approach that included rural roads, drainage and irrigation, schools and clinics (Reference Mohd Ashad and ShamsudinMohd Ashad & Shamsudin, 1997). Planning and development was co-ordinated by the Economic Planning Unit in the Prime Minister’s Department, and the progress of all elements within each administrative district was monitored in an integrated fashion through a ‘Red Book’ that commanded the attention of politicians and civil service administrators at national, state and district levels. The RHS was a major component of this integrated development, such that a district would receive an integrated package that increased physical access to basic education and healthcare, while parallel initiatives addressed its economic needs.

4.2.2 The Rural Health Service

The RHS was government funded. A basic RHS unit served 50,000 population. It consisted of a main health centre (MHC), 4 sub-centres (HSC) and 20 satellite midwife clinics, each with an attached residential facility for the midwife (MCQ). This basic unit was designed to provide ‘integrated curative and preventive health services’ (Reference JayasuriaJayasuria, 1967). Table 4.2 illustrates the services and notional staffing pattern of the basic RHS unit. The number of rural health facilities increased significantly between 1960 and 1980 (Table 4.3).

| Facility | Services | Notional staffing pattern |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Health sub-centre (HSC, 10,000 population) |

|

|

| Midwife clinic and quarters (2,000 population) | Domiciliary midwifery | Midwives (with supervisory nurses from MHC or HSC) |

During the first 10 years, the major challenges included difficulty in matching the rate of facility construction with that of population growth, inadequately trained staff for facilities that had been completed, and prevailing cultural beliefs and taboos that hindered service utilisation. After 15 years of development, by 1975, the facility-to-population ratios showed that only 50% of population coverage targets had been achieved. A community survey showed that 24% of the rural villages in the survey areas were ‘underserved’ (Reference NoordinNoordin, 1978). To increase access, the static facility-based services were supplemented with mobile clinics-cum-dispensaries that travelled by road or river, and dental clinics funded by the government, all providing free access to the population (Reference IsmailIsmail, 1974; Reference Tate Abdullah, Khoo and GabrielTate Abdullah et al., 2005). These teams visited remote villages and provided a PHC package consisting mainly of curative, MCH and immunisation services periodically.

4.2.3 The Influence of the Alma Ata Declaration on the RHS: Community Mobilisation, Enhanced Intersectoral Co-ordination, Referral Systems

By the time of the Alma Ata Declaration (1978), Malaysia had already adopted many of the basic concepts of the Declaration. The serving Director-General of Health, Dr Raja Ahmad Noordin, stated: ‘Malaysia viewed PHC as an extension to its existing health care services’ (Reference NoordinNoordin, 1978). The major contribution of Alma Ata was to provide a fillip for the conceptual enhancement of PHC services by spurring the introduction of community mobilisation, enhancing inter-sectoral co-ordination and strengthening referrals to and support from hospitals (secondary healthcare) (Box 4.2).

Use of trained allied health personnel (particularly nurses and midwives) instead of reliance on doctors. Infrastructure development quickly outstripped the availability of human resources. Rapid but strictly regulated training of nurses and midwives, with registration, defined roles with relevant competencies, and appropriate deployment was a success (see also Chapter 8).

Partnerships with traditional birth attendants (TBAs). In the Malay communities, TBAs (bidan kampung) were influential. In 1967, about 3,000 TBAs conducted an estimated 47% of the 174,000 deliveries (Reference PengPeng, 1979). In some areas, the percentage could reach 80% due to both the shortage of midwives and the belief system of the community (Reference Ali and Howden-ChapmanAli & Howden-Chapman, 2007). Recognising the key position of TBAs in rural communities, the Ministry of Health introduced a training programme for TBAs in 1965 (Suleiman and Jegathesan, n.d.) to change their role. They would recognise the danger signs of pregnancy and childbirth, avoid harmful practices and conduct home visits to encourage women to utilise midwife clinics and health centres for antenatal and postnatal care. They also provided support to certified government midwives during home deliveries. The TBAs were allowed to continue to perform harmless traditional practices such as postnatal massage.

Community mobilisation. Several parallel thrusts mobilised community support. Health officials took advantage of the system of village development committees established by the rural development programmes to mobilise the support of the penghulu (village headman) and his committee for various health issues (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003). Women’s development programmes provided entry points to raising awareness and providing practical avenues for better child-rearing and nutrition. The school health programme provided the vehicle for mobilising school children not only to understand and improve their own lifestyle but also to influence their parents’ health behaviour.

Partnerships with other public sector agencies with grassroots presence. Police posts in rural villages had the function of issuing birth certificates and burial permits. Midwives and nurses obtained data on births and deaths in their districts from the police. Similarly, police communications systems (radios) provided the means for front-line health staff to call for ambulances and assistance during medical emergencies.

Dr Noordin spearheaded community mobilisation to make it an integral complement to expanding health services. Additionally, facility expansion was accelerated such that the RHS configuration was modified to extend the coverage of the basic unit to serve a population of 20,000. Staffing profiles changed accordingly. Emulating the successful experience in one state (Sarawak), midwives were upgraded to become rural (community) nurses and given a wider scope of responsibility (Chapter 8). Accelerated training of nurses and midwives enabled rapid upgrading of the quality of services. Simultaneously, community mobilisation took several forms, with active efforts to encourage communities and families to promote health, prevent illness and utilise health services appropriately. Health staff became focal points for organised community efforts, as exemplified in the rural sanitation programme (Chapter 7). Nursing and midwifery staff gained entry to male-dominated village development committees by working in partnership with sanitation staff. This approach enabled them to promote safe childbirth by sensitising communities to the danger signs in childbirth and pregnancy and encouraging the acceptance of prompt medical intervention to save the lives of mothers and babies. Pregnancy care included supervision of childbirth at home by trained, certified midwives, followed by 10 days of daily postnatal home visits that enabled the visiting health staff to build a rapport with the family and the community while establishing breastfeeding and healthy nutritional habits (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003).

Inter-sectoral co-ordination became a part of service delivery as well as infrastructure development. Child health included growth monitoring, oral re-hydration techniques, breastfeeding, immunisations, food supplementation, female literacy and family planning. Partnership with rural women’s development programmes enabled health staff to raise awareness of hygiene and nutrition. Health topics were integrated into school curricula through interagency co-ordination between the Health and the Education Ministries, and school visits by nurses and dental nurse teams brought basic screening, referral and simple treatment to the doorstep of the expanding school-enrolled population. Partnership with traditional birth attendants (TBAs) reduced unsafe childbirth while giving the TBAs a continuing role in supporting birthing women (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003). Nutrition demonstration sessions by nurses in rural clinics gained popularity. The Applied Food and Nutrition Programme, implemented in districts with high levels of malnutrition, is an example of a partnership with the agriculture, rural development and women’s empowerment initiatives.

Regional disparities in social status and poverty led to targeted poverty reduction programmes. These programmes included initiatives for better access to healthcare and for addressing childhood malnutrition in disadvantaged areas. The prevalence of childhood malnutrition was used as a surveillance tool, while the prevalence of undernourished children was a criterion for identifying low-income families to receive food supplementation as well as assistance with education, housing and employment (Economic Planning Unit, 2004).

Another influence of Alma Ata was to highlight the health needs of remote populations, including the indigenous people (Orang Asli), who had limited access to transport to and communication with healthcare facilities. Mobile teams had to travel over unsealed roads, by river and on foot to serve these communities periodically.

The effectiveness of these measures, in combination with the broader socio-economic development issues discussed in Chapter 3, is evident, for example, in the rising levels of childbirth attended by skilled birth attendants, immunisation coverage and declining maternal and child mortality (Table 4.4) (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). The proportion of deliveries by trained personnel increased from 77.2% (Peninsular Malaysia) in 1975 to 95.2% (Malaysia) in 1996 (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). Referral systems were established particularly for maternity and for infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis (TB). When nurses based in rural clinics referred patients with obstetric problems to hospitals, these patients were given priority and prompt attention. Pregnant women and young children carried personal health cards displaying their pregnancy and healthcare information, thereby facilitating information exchange between PHC and secondary levels of care (United Nations Development Programme, 2005; Reference AwinAwin, 2011). The major communicable disease control programmes established similar referral systems (Chapter 6). The parallel development of rural roads and the provision of ambulances stationed at the MHCs facilitated the movement of referred patients, thereby supporting the referral system. This service delivery system in turn enhanced the credibility and acceptability of health services for the rural population. Senior obstetricians who served in public sector hospitals during that period freely attributed the decline in maternal death to the sterling efforts of rural-based nurses and midwives in identifying complications of pregnancy and childbirth and getting patients to hospital in time for effective interventions (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003).

| 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of delivery | |||

| Government hospitals | 30.01 | 43.91 | 59.1 |

| Other medical institutions | 11.41 | 10.71 | 16.1 |

| Home deliveries | 58.61 | 45.41 | 24.8 |

| Immunisation coverage | |||

| Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) (infant) | 46.6 | 88.2 | 98.7 |

| Diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus (DPT) (3rd dose) | 15.0 | 67.0 | 92.0 |

| Polio (3rd dose) | 15.0 | 72.0 | 91.5 |

| Measles (infant) | 10.0 | 20.0 | 69.6 |

1 Peninsular Malaysia only.

4.2.4 PHC in Urban Areas

Public sector.

During the first three decades after independence, the ambulatory health service component of PHC in urban areas was provided by a combination of government-funded public services, the private sector (funded through out-of-pocket expenditure by users) and non-governmental organisation (NGO) services supported by civil society and government grants. There was very little co-ordination across these sectors. However, these services are collectively credited with raising awareness and acceptance of allopathic medical interventions, particularly among those who had relied mainly on traditional remedies and were steeped in cultural beliefs that were obstacles to the use of effective healthcare.

The public sector hospitals each had outpatient (ambulatory) services that provided walk-in care mostly geared to acute episodes of illness, as well as accident and emergency (A&E) services that were available 24 hours a day. In the larger hospitals, doctors aided by hospital assistants (later re-named medical assistants) were backed by pharmaceutical services (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). These services provided referrals for admission and specialist care when needed. Almost all of these hospital-based outpatient services were confined to curative care, except for pregnancy, for which antenatal and postnatal clinics provided counselling and services, including that for family planning. Additionally, in the larger urban configurations, the local authority (such as the city council) provided maternal and child health services through a network of clinics. These services predated independence and were the prototype that was later used by the RHS for maternal and child health services. All of these services were provided for nominal or no fees, and utilisation rates in ambulatory facilities were very high, resulting in queues and long waiting times. During the third decade post-independence (the 1980s), the state of the overcrowded, understaffed services began to cause concerns about the quality of care. This contributed to the genesis of the Quality Assurance initiative (see later in this chapter and Chapter 5).

Private sector.

The private sector complemented the public sector in urban areas. Medical doctors (GPs) owned and provided healthcare, including dispensing medication through small clinics that operated from modest premises. Most were in ‘shop houses’, that is, two- or three-storeyed premises with the clinic on the ground floor. The higher floors sometimes served as short-stay hospitals for patients and came to be known as nursing homes or as private hospitals. Such premises were flanked by other shops. Most patients paid a fee for the service, which was generally very low, affordable and popular with the urban population. They received ‘one-stop’ care by the doctor, sometimes assisted by trained nurses or medical assistants; medication was dispensed on the spot, and minor surgery was performed on the premises.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

NGOs played a small but very significant role in the development of PHC in urban areas. Some NGOs, such as St John Ambulance and Red Crescent, filled gaps in the services provided by the public sector. Others, such as the family planning associations (FPAs) (Box 4.3) and several associations related to special needs, such as impaired hearing, vision and disabilities arising from illness (e.g. leprosy) or genetics, provided small-scale models of care and strong advocacy that served to mobilise civil society to recognise unmet needs. They established partnerships with the public sector, which provided financial grants. For example, the FPAs received an annual grant of RM 200,000 from the government from 1962 until the early 1980s (Reference Tey, Robinson and RossTey, 2007). In later years, when capacity grew, the public sector took over many of these services and used the care models developed earlier by the NGOs.

The FPAs (now known as the Federation of Reproductive Health Associations, Malaysia, or FRHAM) were largely led by prominent obstetricians and personalities active in civil society. They had the ear of policymakers, although the services they provided were limited mainly to small clinics situated in urban MCH clinics and hospital postnatal wards. The uptake of contraceptives was not impressive. The West Malaysia Family Survey conducted in 1966 found that the contraceptive prevalence rate was only 8.8% (Reference Ahmad, Tey, Kamarul Zaman, Muhd Sapri, Abdul Manaf and YeohAhmad et al., 2010). Advocacy and the service models used by the FPAs contributed to the establishment of the National Family Planning Program under the First Malaysia Plan in 1966 to improve families’ health and welfare and promote national economic development. The programme was expanded and integrated into RHS in the mid-1970s to serve rural and remote communities. The rapid expansion of the MCH and FP services have been a major factor in lowering the infant mortality rate across the country (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003).

Traditional and complementary medicine (TCM).

Although traditional practitioners were and continue to be widely available, there is little information about them. They were not registered, and their practice was not regulated. More recently, there has been stronger oversight of the products they use, and this is discussed in Chapter 11.

4.3 The Second Phase: The Continuing Journey towards Integrated PHC Services (1990–2017)

4.3.1 Drivers of Change

Economic growth continued over the following 30 years, although there were a number of setbacks, including the Asian financial crisis. The population became increasingly urban, reaching almost 70%, and the proportion of teens and young adults increased, followed by an increase in the number of elderly people (Chapter 3). Lifestyles and health-related behaviour, particularly around food and physical activity, began to change. For example, during the 1990s, tobacco smoking and drug addiction were major concerns, while in the 2000s, the obesity epidemic took centre stage (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). As people became increasingly well-connected with the world through media and travel, public expectations of healthcare increased.

Rising healthcare costs competed with other priorities in the national budget and increased pressure on the health sector to consider alternate approaches for healthcare financing (Chapter 9) and cost containment. The voices of civil society became stronger, with a growing dichotomy between conservative and liberal value systems. This generated debates and tension on many health-related issues, such as reproductive health and HIV/AIDS. Additionally, international pressures, first towards achieving Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and subsequently re-aligning towards Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), influenced national health goals (Chapter 6, Case Study 6.1).

All of these interacting forces were drivers that influenced health policy and the evolution of PHC, first towards the provision of a greater range of services to cater for new and emerging needs; second towards better integration between services. Integration and co-ordination were needed to remove institutional barriers between the multiple healthcare services that catered to any particular family and to focus on providing health services to meet the needs of people within their families and communities. The rapid urbanisation also required different modalities from rural settings for the provision of integrated PHC.

The Seventh Malaysia Plan (1996–2000) marked a change for PHC with the establishment of a new PHC division in the Ministry of Health (MoH) (Economic Planning Unit, 1996). The evolving PHC services during this period had two major characteristics. First, in the public sector (mainly MoH services), there was convergence of the hitherto separate services for promotional-cum-preventive health provided at health centres and the curative outpatient services provided by MoH hospitals and health centres. Second, in the private sector, serious stresses emerged in services provided by GPs, associated with issues of financing and competition from public-sector clinics and by specialist practitioners who also provided primary care (Chapter 4, Case Study 4.2).

4.3.2 PHC Services in the Public Sector

The overarching goal of the public sector was to achieve equitable access to more comprehensive primary care. Three threads of interlinked thrusts towards this goal are discernible, namely:

Expanding the scope of PHC services to encompass additional age groups and health needs.

Integrating preventive-cum-promotional services with curative services to address segmentation and compartmentalisation and provide seamless care for individuals, families and communities.

Improving the quality of services to respond better to expectations in the community and professional groups.

4.3.2.1 Expanded Scope of Preventive PHC Services in the Public Sector

During the 1990s, responding to demographic and morbidity trends, the preventive and health promotional services provided by health centres expanded to include additional age groups (adolescents, adults, women’s and workers’ health, the elderly, children with special needs) and health problems, such as mental health and screening for iodine deficiency and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, while the national childhood immunisation programme expanded to include measles, mumps and diphtheria, and Haemophilus influenzae (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.).

The clinic-based services were complemented by community-based programmes. The nutritional surveillance of children and pregnant women conducted in 1988 provided valuable input to the national poverty reduction initiatives and rehabilitation efforts (National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition, 2006). The Food Basket Programme (also known as the rehabilitation programme for malnourished children) for children with poor nutritional gain continued to reach out to poor communities (National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition, 2006). Clinic-cum-community services were also initiated to support anti-tobacco smoking efforts, which included smoking cessation clinics. The health clinic advisory panels (panel penasihat), with local community representatives, worked with health staff on four major areas: healthy ageing, advocacy for immunisation, dengue control, and diabetes and overweight management (Reference Mustapha, Omar, Mihat, Noh, Hassan and Abu BakarMustapha et al., 2014).

Simultaneously, the hitherto rural health services gradually increased their coverage to include urban areas in response to demands from local authorities that had little interest in providing services that did not generate revenue. This required organisational re-structuring, including the transfer of authority, staff and some physical facilities from the local authority to the national MoH, particularly in the metropolitan cities of Penang, Melaka and Kuala Lumpur. It also paved the way subsequently for easier integration of preventive and curative services.

Gaps in and limitations to expansion.

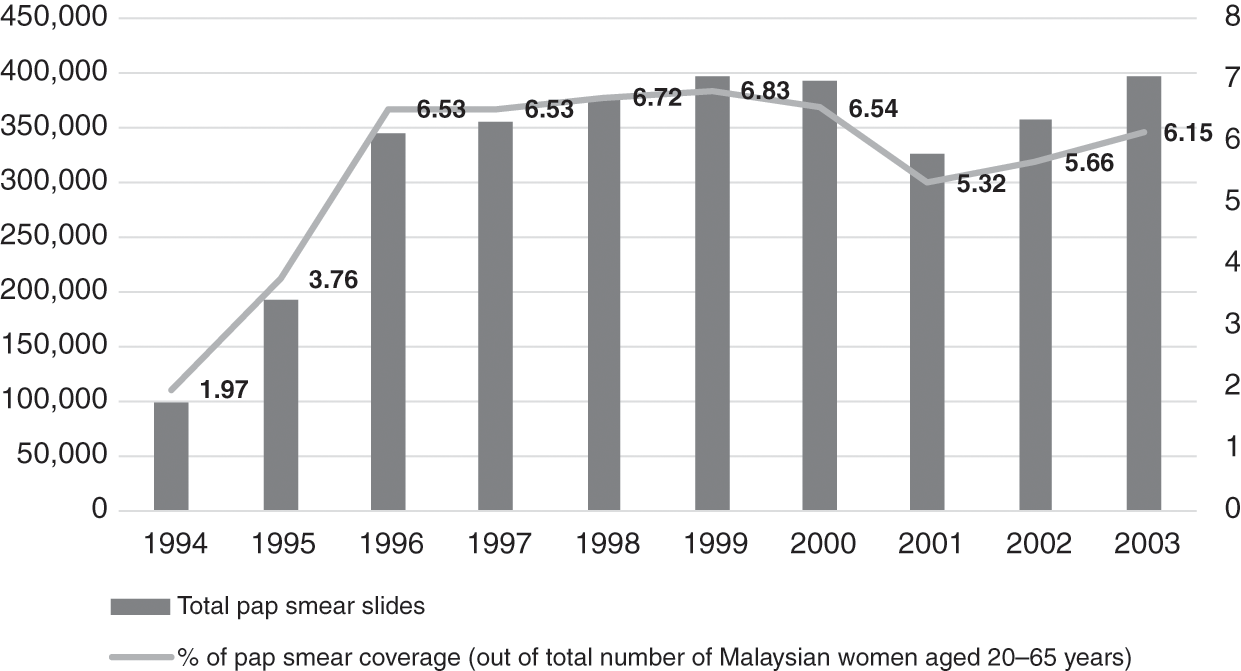

Financial and human resources constraints limited some of the service expansion. For example, cervical cancer screening had already been planned to incrementally cover larger sections of the target age group, but laboratories could not cope, and the turnaround time was slow. Screening reached only 6% of eligible women (aged 20–65 years) between 1996 and 2003 (Figure 4.1) (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2005), and follow-up call services were inadequate (Reference Wong, Wong, Low, Khoo and ShuibL. P. Wong et al., 2008). Also, other components of the health system interacted with PHC services in the public sector to initiate, facilitate or limit the expansion of PHC services. Examples are summarised in Box 4.4.

Examples of Limiting Factors

Finance: Dictated the speed and influenced the scope of expansion. While new programmes were added, some existing programmes, such as family planning and cervical cancer and breast cancer screening programmes, failed to gain traction.

Workforce: Upgrading the competencies and recruitment of new categories with different competencies needed, such as finance, training and managerial support. For example, the lack of trained staff hampered the ability to provide rehabilitation, occupational therapy, home visits and home care nursing services for the elderly.

Examples of Enabling Factors

Medical products and technology: Additional affordable vaccines (measles, mumps and rubella (MMR), hepatitis B, human papillomavirus (HPV)) and the availability of simple field tests (G6PD and hypothyroidism screening) enabled the expansion of services. Staff training and financial support enabled this expansion.

Health information: Nutritional surveillance identified anaemic pregnant women and malnourished children and enabled the provision of food baskets for them as part of multi-sectoral poverty reduction; Teleprimary Care enabled better management of diabetes and hypertension by providing data for targeted monitoring and follow-up.

Governance: Community mobilisation and inter-sectoral co-ordination supported strategies for reducing disease risk factors. Grants were allocated for promotion, prevention, early screening and rehabilitation care. Illustrative examples are the mobilisation of teens through peer-to-peer counselling within school communities for targeted purposes such as tobacco smoking and drug use (PROSTAR) and for more general behaviour change purposes such as healthier lifestyles (Doktor Muda) (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2005). New legislation established standards for care, including care of older people in private healthcare facilities, and also mandated the sale of iodised salts in districts with high risk of iodine deficiency disorders.

4.3.2.2 Integration of Preventive and Curative Services in the Public Sector

Prior to the mid-1990s, curative PHC services were provided by:

Outpatient departments (OPDs) of public sector hospitals and some satellite clinics for free or for a nominal charge.

Public sector health centres and dispensaries, also free or for a nominal charge.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, two related organisational changes within the MoH led to better integration of preventive and curative services. First, the implementation of a policy decision to move OPDs out of hospitals and into health centres began in the late 1990s and continued incrementally over the next decade. Second, this move was followed by the re-organisation of services in the health centres to better serve the goal of developing people-centred PHC.

Transfer of OPDs.

Historically, hospital OPDs primarily catered for acute episodes of illness, rarely providing health prevention or promotion, and were not geared for the continuity of care essential for non-communicable disease (NCDs). Conversely, health centres had separate arms – the family health arm had good competence for providing preventive and health promotional services for family health aimed at clients in various phases of the life cycle (pregnancy, childhood, adolescence, old age), including individuals, families and communities on a long-term basis. However, the outpatient arm of the health centres mainly provided for walk-in patients. The utilisation of OPD services evolved, with the health centres gradually overtaking the hospital OPDs in terms of volume of utilisation (Figure 4.2).

Additionally, by the late 1990s, the proportion of patients with illnesses such as hypertension and diabetes, which require long-term management, was increasing. Meanwhile, public sector hospitals had difficulties managing outpatient services (OPDs), as their focus was mainly on secondary and tertiary care. Therefore, a policy decision was implemented to transfer OPDs from hospitals to health centres.

Re-organisation of health services.

The outpatient services in health centres were re-vamped to cater to the integration of preventive and health promotional services with illness management (Economic Planning Unit, 1996). The health centres adopted a new approach that integrated basic PHC concepts in addressing the continually expanding initiatives required to deal with NCDs. Box 4.5 summarises the concepts involved, and the illustrative case study on REAP-WISE (Reviewed Approach: Wellness, Illness, Support Services, Emergency Information) elaborates on the initiative. Imaging, laboratory and pharmacy facilities were upgraded progressively as staff and physical infrastructure became available (Economic Planning Unit, 1996; 2001). Communication between primary, secondary and tertiary care was strengthened, and information systems were upgraded to include electronic personal medical records that facilitated the integration of information from the various services that catered to each patient and family (Economic Planning Unit, 2001).

The health centre services renewed the PHC concept with a new approach to accommodating its additional services, namely:

1. Preventing and reducing disease burden by treating the ill, managing those with risks and preventing the onset of preventable risks.

2. Enhancing healthcare delivery for fast access to safe and high-quality services with greater comfort in a hassle-free environment.

The wellness focus covers the life-course from antenatal to child and geriatric age for early identification of and management of medical conditions. All new activities for wellness are mapped against age group needs. Teams oversee policy development for the collective activities for each age group in order to integrate workflow processes, accounting for monitoring indicators, quantity and quality of human resources required, the diagnostic equipment, pharmaceutical requirements, and physical space for these activities. These workflow processes are then phased in at clinics nationwide.

Gaps and limitations to the integration and re-organisation.

This re-organisation process required the re-allocation of budget and human resources between hospitals and health centres, and it also required re-engineering health information systems to provide real-time access to patient information for care providers at primary and secondary level. Table 4.5 illustrates the gaps and challenges in integration and re-organisation as well as the action taken to address such challenges.

| Gaps and challenges | Action taken | |

|---|---|---|

| Finance | Limited | Transfer of OPDs was done incrementally over a period of more than a decade |

| Health workforce | Rapid turnover of staff, particularly junior doctors who needed rotational postings as part of career development |

|

| Medical products | Hospitals and health centres have separate budgets for pharmaceuticals – it was difficult to estimate the portion of hospital pharmacy budget needed for OPD as separate from inpatient care | State-level pharmacy departments took over budget management for pharmaceuticals for both health and hospital services |

| Service delivery |

|

|

4.3.2.3 Focus on Improving Quality of Care

During the late 1980s, the rising expectations of the public, as well as the strong commitment of professional leaders to quality of care, led to the introduction of a variety of quality improvement initiatives in the MoH (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). The scope of quality improvement was defined as including technical quality of care, client satisfaction and resource utilisation. This compares well with the statement 30 years later by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank defining the ‘measurable characteristics of quality as effectiveness, safety, people-centeredness, timeliness, equity, integration of care and efficiency’ (OECD et al., 2018). The key initiatives included raising the levels of competence in the PHC workforce and introducing systematic monitoring of quality followed by measures to identify and address systemic weaknesses that contributed to inadequate quality.

Higher levels of competence in the PHC workforce.

Medical officers, who were the front-line providers of care for illness episodes in health centres and OPDs, had no post-graduate or vocational training and had limited ability to manage more complex and chronic conditions, such as NCDs and mental illness. Years of effort by professional leaders (Reference RajakumarRajakumar, 1984) culminated in universities offering a new post-graduate training programme of Family Medicines, while the MoH created a new cadre of specialist: the family medicine specialist (FMS). This new category of FMS was expected to provide leadership in upgrading the quality of primary care services that included a more holistic approach of seamless care for health promotion, disease prevention, illness management and rehabilitation for individuals and families (Reference AwinAwin, 2004).

In tandem, the competencies of nurses and medical assistants were upgraded. The local production of allied health professionals, such as diagnostic radiographers, medical laboratory technologists, physiotherapists and dieticians, was stepped up with a higher level of qualifications and was modernised through integrated training approaches. Previously, the services of these allied health personnel were available only in hospitals, but now they were added to PHC teams (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2006).

Quality monitoring and improvement strategies.

Hitherto focused on monitoring and improving ethnic and regional disparities in equitable access to care and health outcomes, PHC services added new dimensions to their performance monitoring (Box 4.6). Table 4.6 shows illustrative examples. The conglomerate of activities created a ‘bottom–up’ quality culture within the organisation.

Table 4.6 Quality monitoring and improvement: examples of experiences in primary care

| Approaches to quality improvement | Examples | Benefits derived from the initiative |

|---|---|---|

MoH Quality Assurance Programme adopted the approach of:Nationwide monitoring of selected indicators of system failure, for:

| During the early stages of the programme, indicators were:

|

|

| Participation in nationwide quality improvement strategies by health districts, health centres, hospital OPDs, laboratories and pharmacies |

|

|

Box 4.6 Dimensions of quality that were monitored and improved

Workforce skill levels and competence

Outcomes of prevention and management of illness

Client satisfaction

Resource utilisation

4.3.3 PHC Services in the Private Sector

In the private sector, doctors (GPs) provide ambulatory non-specialist curative services on a fee-for-service basis. In the 1980s and 1990s, as rural to urban migration increased and the economy improved, the size and utilisation of the private sector increased rapidly (Figure 4.3).

Box 4.7 summarises the characteristics of GPs, who provide about half of ambulatory care in Malaysia. Despite their importance in the health sector, governance and financing arrangements result in GPs having few incentives to provide prevention and promotion services. Their fee schedule is per visit and has not been adjusted for inflation over the past 15 years (Reference MaharajahMaharajah, 2018). It is not geared to reward the time and effort spent on health promotion. For many GPs, the fee is so low that it is not financially sustainable, and they rely on the sale of medications to maintain financial viability. Patients are free to move between doctors; doctor-hopping is frequent and therefore continuity of care could be compromised, and it can be difficult to build a trusting and long-standing relationship between providers and clients and their families. Additionally, there is no restriction on patients seeking primary care from doctors who practise as specialists in any discipline in the private sector. Therefore, specialist doctors are in direct competition with GPs.

Box 4.7 What are GPs?

GPs are medical doctors.

Few have any specialist or vocational training to function as providers of comprehensive PHC such as the requirements for GPs in the United Kingdom or Australia.

Most GP clinics are urban and semi-urban, with fewer than six staff members. They use private laboratory and imaging services.

GPs prescribe and dispense medicines.

The public utilises GP services largely for acute illness episodes while largely visiting public PHC clinics for more chronic and complex conditions (Table 4.7).

Table 4.7 Top three reasons for encounters in public and private clinics

| Rate per 100 encounters | |

|---|---|

| Public sector primary care clinics | |

| Hypertension | 31.3 |

| Diabetes | 22.5 |

| Lipid disorder | 18.5 |

| Private sector clinics | |

| Fever | 28.3 |

| Cough | 26.5 |

| Runny nose/rhinorrhea | 19.4 |

A Quality and Costs of Primary Care (QUALICOPC) study showed that three-quarters of the patients who visited private clinics reported that they did not have a primary doctor to follow up on their condition (Reference Sivasampu, Mohamad Noh, Husin, Wong and IsmailSivasampu et al., 2016). Health information systems are underdeveloped. Few patients’ medical records are computerised and there are no incentives for recall and follow-up of patients who require long-term management. There is no systematic monitoring of the quality of care (Reference Sivasampu, Mohamad Noh, Husin, Wong and IsmailSivasampu et al., 2016). In contrast, for example, in Australia, there are targeted incentives for private sector primary care providers to support immunisation and cervical smear testing and for installing information technology (Reference KhooKhoo, 2002).

Additionally, GPs face serious economic challenges arising from the introduction of third-party administrators (see Case Study 4.2). On top of that, medical insurance schemes generally do not cover ambulatory care. In a recent survey, 70% of GPs interviewed cited as serious threats market competition from community pharmacies, and 55% cited market competition from the public sector 1Malaysia clinics (Reference KennyKenny, 2017).

The policy environment in which private clinics currently operate presents obstacles to preventative and chronic care. This shows how stated goals, such as the aim of the MoH to increase integration and comprehensiveness of primary care, may differ from systems outcomes. Policies and resources for public clinics have enabled significant advances toward these goals. However, private clinics operate under fee structures, lack of integrated information systems and other policy obstacles that create barriers to preventative and chronic care. Private GPs have persisted in health promotion despite these obstacles (Table 4.9). The MoH needs to invest in an enabling system for private GPs to sustain and maximise their contribution to comprehensive primary care.

4.3.4 Traditional and Complementary Medicine

TCM is responsible for about 6% of expenditure on ambulatory care. For the first 50 years after independence, the allopathic healthcare system adopted an attitude of peaceful co-existence with TCM, responding only to curb practices that were known to be dangerous to health. This chapter is hampered because there is little empirical evidence of TCM practices or their outcomes. During the last 10 years, initial efforts were directed at establishing a database of practitioners and practices and developing regulations to set standards for practitioners (Reference Mahmud, Tahir, Ida Farah, Ami Fazlin, Sondi and AzmanMahmud et al., 2009; Division of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 2017). These were the first steps in integrating TCM into the country’s PHC system. Case Study 11.1 provides insights into some of the challenges.

4.3.5 Outcomes of PHC in the Public and Private Sectors

Access, satisfaction, quality and continuity of care.

A QUALICOPC study showed that patients generally did not perceive barriers to access (physical and financial) to care and were satisfied with the care they received at both public and private clinics (Table 4.8) (Reference Sivasampu, Mohamad Noh and ChinSivasampu et al., 2015; Reference Rajakumar2016).

Table 4.8 Access to and satisfaction with primary care

| Patients’ perceptions of accessibility of primary care and satisfaction with care | % of patients interviewed | |

|---|---|---|

| Public clinic | Private clinic | |

| Clinic not too far away | 77.5 | 85.4 |

| Opening hours not restricted | 59.2 | 73.3 |

| Able to get a home visit | 43 | 18.9 |

| Out-of-office hours | 58.3 | 68.1 |

| Never postponed or abstained from a visit when needed | 80 | 85 |

| Satisfied with the duration of the consultation | 96.7 | 96 |

The large majority of doctors in both public and private clinics were reportedly involved in health promotion as part of their normal patient contact, though not in group sessions (Table 4.9).

Table 4.9 Doctors reporting involvement in health promotion during routine patient encounters

| Proportion (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Public clinic | Private clinic | |

| Smoking | 88 | 95 |

| Diet | 92.8 | 97.9 |

| Problematic use of alcohol | 52.9 | 66.5 |

| Physical exercise | 85.5 | 98.7 |

Referral linkages with secondary and tertiary care were not strong (Table 4.10), particularly in terms of feedback from secondary to primary care level and in horizontal communication between primary care providers.

Table 4.10 Referral experiences reported by doctors

| Proportion (%) of doctors stating: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usually/always | Occasionally | Seldom/never | ||||

| Public clinic | Private clinic | Public clinic | Private clinic | Public clinic | Private clinic | |

| Received patient records from previous doctor | 36.2 | 7 | 51.6 | 39 | 12.2 | 54 |

| Used referral letters | 99 | 91 | ||||

| Obtained feedback from specialists | 19 | 19 | 30.8 | 31 | 50.2 | 50 |

| Obtained discharge report from hospital | 271 | 221 | 13.72 | 292 | 58.4 | 49 |

1 Within 1–14 days.

2 Delayed by >14 days.

As the doctor-shopping phenomenon was observed and there was a lack of longitudinal continuity at private primary care clinics (Reference Sivasampu, Mohamad Noh, Husin, Wong and IsmailSivasampu et al., 2016), it is not surprising that significant differences were noted in aggregated performance indicators of quality of care between public and private sector primary care, with the public sector surpassing the private sector (Table 4.11).

| Percentage of: | Public | Private |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled diabetics1 | 38.1 | 35.5 |

| Hypertension management2 | 44.1 | 39 |

| Hypertension management3 | 50 | n.a. |

1 MHSR (Malaysia Health Systems Research) analysis using NHMS (National Health and Morbidity Survey) 2015 data. Fasting blood glucose of 4.0–6.1 mmol/L or non-fasting blood glucose of 4.4–8.0 mmol/L.

2 MHSR analysis using NHMS 2015 data. Target blood pressure of ≤140/90 mmHg.

3 MHSR analysis using Teleprimary Care data, which relates only to care at MoH clinics.

n.a. – not available

4.4 Summary of the Malaysian Experience

Although the PHC services predated the Alma Ata Declaration of 1978, the guiding principles used in Malaysia were akin to those formulated in Alma Ata. Over 60 years, these services evolved in incremental stages in response to population dynamics and behaviour, changing disease patterns and economic pressures, taking advantage of local opportunities and recognising constraints. The government assumed responsibility for free public sector services that led the way and dominated the subsequent evolution of PHC in the country. Achieving equitable access for a wide range of ‘essential services’, including PHC services, has remained a cornerstone of the evolution. These services included preventive and health promotional services, including nutrition, as well as curative services provided at hospital OPDs and by the private sector.

PHC services retained the focus on people throughout the evolution – variously reaching out to communities to mobilise them in improving or sustaining health. The process of evolution saw a progressive expansion of the range of preventive and promotional services – beginning with pregnancy, childbirth and infancy and progressing through each age group to old age while simultaneously addressing specific localised concerns, such as iodine deficiency and mental health, as they arose. The parallel evolution of ambulatory curative services saw a progression from managing acute illness episodes to dealing with illnesses that require long-term care, such as hypertension and diabetes. The evolutionary process recognised the benefits of merging the parallel development of preventive/promotional services with the curative stream, and the system was able to accomplish rather complex organisational re-structuring to achieve such merging.

The other cornerstone of the evolution was the continuing thrust to improve quality. The features of the success in Malaysia are: strong and sustained leadership and commitment to quality; adherence to basic principles of quality improvement, including monitoring; and improvement that originated from the service providers themselves, thereby reducing the fear of punitive repercussions and increasing accountability and transparency.

Several challenges surfaced from time to time. As elaborated on in Chapter 8, some were addressed successfully, while others continue to haunt the evolutionary process. For example, the evolving profile of a workforce with higher qualifications has created demands for higher remuneration and better career paths. The workforce in the public sector PHC service is part of the larger civil service in the country. Hence, change is fraught with repercussions. Meanwhile, the private sector is reluctant to absorb higher-paid categories and prefers task-shifting, for example, using nurse assistants in place of trained nurses.

In the past, the private sector has complemented the public sector by providing care for those who were able to pay out of pocket for prompt and convenient care. The last couple of decades has seen publicly funded primary care growing faster than the private sector. While the public sector moves closer to comprehensive primary care and keeps an eye on quality and responsiveness, the private sector is struggling with issues of governance, financing, skills in the workforce and disincentives to move towards comprehensive care. There is a risk that public perceptions of public and private services will change. Wealthier sections of the population might change their health-seeking behaviour accordingly and drift towards the highly subsidised public sector despite being able to afford private services. This would have a negative impact on PHC by overburdening the government budget. Efforts to establish a more collaborative model of operation have been repeatedly frustrated by political pressures and priorities.

Box 4.9 System observations: overcoming limits to growth

The development of PHC clearly illustrates the systems concept limits to growth, in which a previously successful strategy runs into a new limitation that requires a new approach. We see in this chapter the rapid expansion of maternal and child health clinics to improve coverage, followed by the expansion of services, which in turn led to the development of multi-disciplinary teams. Each of these developments came about as the prior strategy encountered limitations in improving population health, and they required substantial re-alignment of clinic organisation, practices and personnel. The growing challenges of chronic care and health promotion in urban settings will probably require similar experiments and paradigm shifts among public primary health clinics.

4.5 Key Messages from Malaysia’s Experience

4.5.1 What Went Well?

PHC is part of rural development; PHC benefits from the development of education and communication and contributes to rural development.

The cornerstone of PHC is equitable access to services; close linkages with secondary care and community mobilisation are key; urban settings require different modalities from rural settings in the provision of integrated PHC.

Appropriately trained and supervised allied health workers provide low-cost, high-impact PHC.

Systematic monitoring, focused on identifying and resolving systems issues rather than creating a blame culture, improved quality of care.

4.5.2 What Did Not Go So Well?

The dichotomy between the public and private sectors in terms of financing and governance continually generates challenges that have not been addressed adequately.

The rigid structure of the civil service (including the public sector health services) and the fee-for-service mechanisms of the private sector continue to be major constraints in the development of PHC.

4.5.3 Trends and Challenges

Epidemiologic, demographic and technological trends will require flexible adaptive responses from PHC.